1

THE BUSINESS CASE

FOR ONBOARDING

An R&D manager at a large consumer electronics firm wanted to improve the time it took to get new hires working at their best. This manager felt that a more comprehensive onboarding program would help new hires gain better and quicker access to the specialized knowledge they needed to excel in their jobs. Yet when our client tried to get his chief technology officer to invest in new hire onboarding, he received an unenthusiastic response. More effective onboarding seemed like an intriguing idea, but it wasn’t worth funding over other priorities and wasn’t clear what the payoff could be.

Few operating leaders today appreciate the full value that effective onboarding can deliver. This is understandable given onboarding’s position as an emerging discipline with only a short history. This is a shame because on an intuitive level, onboarding makes a good deal of sense. The dollars we spend to recruit Grade A talent have mounted over the past 20 years because of a number of factors, including tightening of the labor force and the increasing value of knowledge workers in a service-based economy. Other factors, as some have argued, are the wider emergence of external recruiters who have an economic interest in fostering higher salaries; talent shortages; the never-ending cycle of hire, attrit, and rehire; and the associated stream of finders’ fees. In fact, the cost of attracting talent approaches 30% of a new hire’s annual salary. Imagine the added value if firms possessed a centralized, focused, properly resourced function to incorporate talent into the firm, so there was less of a need to rehire.

It’s one thing to talk about adding value, and quite another to provide hard numbers and explain exactly where those numbers originate. This chapter builds a quantitative business case for dramatically enhancing and broadening the way firms bring new hires into the fold. It begins by examining the economics of onboarding, quantifying typical returns that can be expected. It then describes in more detail the specific business objectives and results firms can achieve with a strategic program in place. But this is only part of the story. The second half of the chapter attacks the problem from the employee’s viewpoint by examining the new hire’s personal needs. Employees who are enthusiastic about their work and their careers are usually strong and productive, and a well-designed onboarding experience satisfies them far better than an inconsistent, haphazard one. The chapter closes with a detailed and thorough economic analysis across industries. Using benchmark data from 25 leading companies across six industries, the prospective impact for your company and your shareholders is measured and illustrated.

It is hoped that this chapter will provide change agents inside organizations with the business case they need to spark serious discussions about onboarding with senior decision makers. If most leaders today believe their firms can’t afford an effective onboarding program, this chapter’s material is designed to convince them of the very opposite: Their firm cannot afford not to invest in one.

The Economics of Onboarding

The first step in building the case for onboarding is to estimate the hidden value that typical firms can hope to recover via a strategic program. To arrive at some hard numbers, we took a sample of Fortune 500 companies across six major industry sectors.

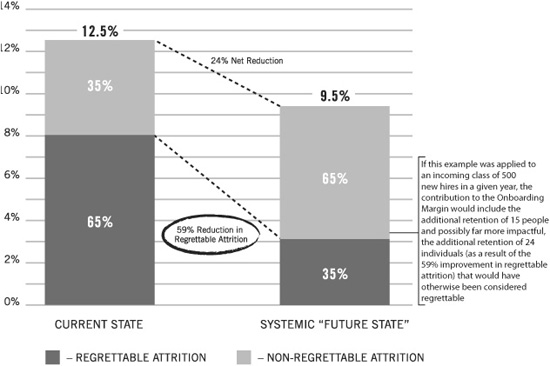

We assessed the impact of attrition of new hires on the overall cost structure and its impact on profit. Based on our research, on average across industries we believe that companies experience approximately 13% attrition of new hires in the first year, and some of that constitutes “regrettable” attrition (productive recruits with great prospects who choose to leave) as opposed to “non-regrettable” attrition (unproductive and low prospect workers leaving the firm). We asked ourselves, what if a strategic onboarding program could invert the common ratio of regrettable attrition? That is, instead of having 65% of our attrition made up of regrettable losses, what if we had 65% of our attrition made up of non-regrettable losses?

We determined that an approximate 25% reduction in total attrition levels was a reasonable goal and would represent a clear savings to a firm in terms of the replacement cost the enterprise would have to pay to recruit new employees. Yet this was only the beginning of the value effective onboarding could bring in this model. To get a more complete measure of this value, we also factored in the opportunity costs of regrettable attrition. When you put a new hire in, say, a quality improvement job and she or he doesn’t make it in the role because of poor onboarding, the loss includes all of the improvements to your quality program that are not happening during the failed ramp-up period, the departure period, and the new search—value that is lost forever. This loss may show up as rework cost, warranty cost, and a reduction in brand equity as customers grow frustrated with your company’s products or services. Although difficult to quantify in a simple analysis, these losses are significant, and they need to be reduced through more effective onboarding.

As the preceding discussion suggests, onboarding does not just offer an opportunity to reduce the overall attrition level. Rather, it also aims to improve the overall attrition mix (regrettable versus non-regrettable loss, as represented by Figure 1.1), which can have an even greater impact.

The objective of onboarding now includes retaining more of the people you want to keep, and reducing the proportion of your head count loss that is made up of regrettable attrition (i.e., retain more people you want and lose more people you are happy to see separate). The most exciting part of this attrition gain is that although it will affect the short-term, day-to-day productivity of the organization, its larger impact will be in the form of what the retained employees—who otherwise would have been regrettably lost—will do for your business in years to come. This is potentially a non-linear relationship, as some of these new hires may provide a truly big impact down the road. This is the game you need to be changing.

Another gain from onboarding relates to the productivity of all new hires. Effective onboarding can shorten the time it takes for the average employee to achieve expected productivity levels. The time (and level) will vary depending on the role, function, and company in question.1 To quantify the potential gain from strategic onboarding, we calculated what it would be worth if we could reduce the time to productivity. We then asked what it would be worth if we could improve the average level of productivity—in effect, redefine what we expect out of a prospective new hire with regard to overall productivity, or contribution. Consider the situation in which, before an effective improvement, a firm deemed a new customer service representative “productive” when he could handle eight calls an hour. What if we were able to produce an entirely new form of value for the enterprise, maybe in the form of the representative’s ability to connect the dots between calls, actually detect patterns in customer issues, and possess the motivation and know-how to properly inform product development (or pricing, or channel strategy, mergers and acquisitions (M&A), or any other critical business activity)?

Figure 1.1 The Gain from Both Level and Mix of Attrition to the Onboarding Margin

Figure 1.2 summarizes the potential productivity gains attributable to strategic onboarding for those new hires who stay with the organization. The top curve represents the level of competency a typical firm could expect to see in new hires over time thanks to a more effective program. The bottom curve represents the existing progress of productivity performance over time. As the graph shows, new hires operating under a more effective program would get a jump start on their jobs, reaching maximum productivity—what the organization would define as 100%—some time between day ninety and the one-year mark, well before employees at the firm might currently reach maximum productivity (see Figure 1.2).

Figure 1.2 The Onboarding Margin

The area of the graph represented by the darker gray area is the entirely new value firms may hope to create by readying and equipping new hires to operate on a new level of redefined expectations. As the graph shows, this new value can be realized in the course of Year One and will continue to develop well into the future as employees come to excel in their jobs. Overall, new hires become more productive more quickly, and they operate at that higher level as part of the new steady state. This, combined with the gains attributable to lower attrition and better attrition mix, yields what we term the Onboarding Margin.TM

Onboarding Objectives and Business Results

This exercise has hopefully provided you a rough sense of how much value more effective onboarding can unlock. To explore further how onboarding can add value for particular enterprises, let’s consider the many specific performance improvements and business results individual managers can hope to accomplish with a strategic program in place.

To the extent that most leaders today think about enhancing new hire onboarding, they usually have at least the following business result in mind: Decreasing the time and money devoted to serving new hires. Companies do spend a fair amount of direct spend on onboarding (in addition to indirect spend, which includes all the costs associated with unproductive new hires), much of it wasted because of their insufficiently organized and poorly designed efforts. An effective onboarding program can address this basic requirement and help cut waste in a number of ways. For instance, many companies have employees fill out paper-based forms, which in turn means the company needs extensive administrative departments to collect, organize, and collate the data. By standardizing and having employees read and complete forms online before their start dates, you can drive cost savings and compliance while also creating a potentially more interesting first day (as time is freed up to tackle far more engaging experiences). New hire training programs offer another example. Currently, many programs are unable to address new hires’ needs in a number of areas. Lacking standardized information, hiring managers are left to improvise their own solutions to integrate the new hire. A more effective onboarding program avoids the duplication of efforts, saving time and money and avoiding needless frustration for the new hire and his or her manager.

To help drive efficiencies, minimize waste, and allow for better new hire experiences, many companies invest in software to administer the process. What most leaders don’t realize is that minimizing this Day One and early entry waste is actually the least that strategic onboarding can deliver. Minimizing Day One waste is a decent opportunity. In fact, sometimes it’s helpful to make greater efficiency as the primary objective when getting a program off the ground. By delivering results there, you’ll have momentum and have an easier time getting buy-in for subsequent investments.

Yet managers and executives shouldn’t make the mistake of limiting the idea of onboarding to a piece of software or the single business result of minimizing waste. These cost savings are largely a one-off savings opportunity, and they exclude the far greater upside. Table 1.1 lists bigger ways in which strategic onboarding will help a firm improve performance. It also lists specific business impacts—including minimized waste—that firms can expect to see as a result of achieving their improvement objectives.

As Table 1.1 suggests, a solid onboarding program can deliver much more than simply reducing administrative cost. Some of the objectives listed here (e.g., attrition) are easier to quantify in their business impact than others (e.g., improvement of the employment brand). It’s also important to realize that no single strategic program, no matter how well conceived, can hope to deliver on every single objective; in fact, many companies go wrong precisely when they attempt to tackle every objective at once. As discussed later, the key is to assess which objectives will have the biggest impact to your company and then devise a customized program focused on delivering on those objectives.

Table 1.1 Outcomes from Strategic Onboarding

Let’s run through the onboarding improvement objectives and explain how strategic onboarding can make a big difference:

• Knowledge transfer. Today a lot of enterprise value is derived from the knowledge of existing employees. Firms widely recognize employee know-how as a company asset, even if it doesn’t appear on the balance sheet. Many companies have invested a lot in trying to distill employee know-how into a formal knowledge management system. When an employee transfers out of a position or leaves the company altogether, knowledge loss always occurs. New hires represent a great and unique opportunity to transfer the most important knowledge of the enterprise to the future workforce and future leaders. This issue is even more pronounced given that a large number of experienced Baby Boomer employees will soon retire. Strategic onboarding helps by offering mentor and apprentice programs, and developing and engineering the significant relationships that new hires require to learn from veteran employees, thus creating an effective knowledge transfer program.

• Engagement levels. Employee engagement2 is critical for any labor-dependent business. In fact, engagement affects several of the business impacts on the right side of Table 1.1—most notably time to productivity, level of productivity, level of attrition, and attrition mix. High performers and “high prospects” who are not sufficiently engaged operate at mediocre levels and soon begin a job search. Ironically, low performers (or low prospects) also maintain mediocre output levels, but unfortunately they are more likely to stay on the job. Both of these are terrible outcomes for the organization. A study of professional services firms found that offices with engaged workers were over 40% more productive.3 Other studies have found that engaged workers are more customer-focused and profitable, and less likely to leave their employer. As shown later in this book, strategic onboarding fosters engagement by helping new hires get excited about their work, their career prospects, and the enterprise’s mission.

• Employment brand. All companies have employment brands in the minds of current and prospective employees, recruiters, and career counselors. Sometimes these brands are more pronounced and positive, as in the case of firms who win “best place to work” awards. If you’ve engineered a system that produces more positive experiences more often, the message will get out. A firm’s reputation will improve, making future prospects easier to identify and cheaper to recruit. Moreover, you will attract the kinds of new hires that your firm desires; that is, those attracted by the specific cultural and performance values your brand conveys. Negative experiences produce the opposite result by eroding the firm’s employment brand through negative word of mouth.

• Automation and standardization. We estimate that 80% or more of medium and large businesses have onboarding processes that are tedious and paper based, require multiple steps of manual administration, are deployed across the enterprise in inconsistent ways, lead to haphazard and wasteful outcomes, inefficiently deploy resources challenging new hire readiness, and create frustrating experiences for new hires and hiring managers. Software can make this a more pleasant and lower-cost experience for everyone involved.

• Consistency of experience. Many companies with existing, piecemeal programs possess pockets of excellence around onboarding, whether in specific functional areas, specific locations, or other organizational units. A strategic approach determines and applies best practices across every part of the enterprise that brings in new hires. It helps firms avoid the bitterness that arises when some employees enter smoothly, while others have less positive experiences. In Columbia, South Carolina, The Sisters of Charity Providence Hospitals, has vastly improved its onboarding by standardizing its orientation program. Retention rates for new nurses rose from 78.2% in 2005 to 86.1% in 2007, whereas the retention rate for new graduates rose from 60 to 94%.4

• Accountability—roles and responsibility. Too many onboarding systems flounder because stakeholders do not know what role they have in the system, they are not provided sufficient guidance and support, and nobody is holding them accountable for fulfilling their responsibilities. Strategic onboarding programs perform better because clear delineation of roles and accountability for performance is baked in. Systems are established to provide support at the right moments, using the right tools.

• Organizational transformation (business and/or cultural). One of the most exciting and strategic long-term business results an onboarding program can provide involves organizational transformation. Given the high rate of employee-based renewal, a fantastic opportunity exists to transform a business by enlisting new hires in a mission of change—either business change (e.g., entering a new channel or a new business) or a cultural change (e.g., a new way of behaving). New hires need to know that their firm is enlisting them as change agents; otherwise, they’ll think that company veterans have bought into the change, although in many instances they have not. New hires also need to understand the organizational benefits of change and why change presents both a challenge and a thrilling journey for them. When a strategic onboarding program properly mobilizes new hires as a force for change, the impact on a firm’s bottom line can be profound—certainly far more significant than the one-off cost savings that many firms now mistake as onboarding’s basic benefit.

• Other/unique to organizations and circumstances. All firms are unique. Because a strategic program design includes a comprehensive diagnostic phase (detailed in Chapter 8), your company will have a chance to discover improvement objectives that are unique to you and that comprise big opportunities for the organization.

Knowledge Transfer: The Case of Reliance Industries, Nagothane Manufacturing Division (India)

To hasten the learning speed of new engineers at its chemical plants, Nagothane trained fifty-one mentors and embedded them with younger engineers for periods as long as nine months. The firm matched mentors and protégés based on the compatibility of their respective training and learning styles. Employees noted their progress on an online portal monitored by senior executives. The result: Time-to-readiness has plummeted from a year to six months. Nagothane also supports a separate online learning portal on which employees can report lessons learned as a result of their experiences. On one occasion, knowledge shared on this $60,000 portal allowed the company to avoid a plant shutdown, saving it $4.3 million.

Source: ASTD 2008 BEST Award. T+D, October 2008.

Now that we’ve looked at some key improvement objectives for effective onboarding programs, let’s briefly consider some of the business impacts firms can see when these objectives are realized. Figure 1.2 has already evoked the kinds of substantial productivity gains strategic onboarding can bring. Productivity is critical—and we’ll spend more time exploring it in a minute—but there is a lot more to achieve. With a strategic program in place, firms find themselves better able to meet human capital demands to realize their business plan. Attrition improves (in both level and mix). Labor and recruiting costs also diminish, as do onboarding administration costs. Of course, business impacts don’t correspond one-to-one with the program objectives; many objectives, once attained, can lead to several positive business outcomes, and business outcomes can in turn arise out of the attainment of many of the program objectives listed on the above Table 1.1.

Onboarding and Enhanced Productivity: A Closer Look

Although well-designed onboarding programs have many components and objectives, optimal programs have one leading goal in mind: to maximize the productivity of an organization’s employees. In this way they contribute to an organization’s bottom line. Improving output per employee maximizes the revenues created by or operating costs reduced by each employee, while minimizing the cost of employing these value-creating strategies. This section provides a framework for analyzing productivity and understanding the impact onboarding can have.

Onboarding drives productivity by serving as a multiplier of the key variables that contribute to employee output. Let’s first define these variables and describe how they come together to yield output. We developed the following expression to describe employee output—or New Hire Contribution—as a function of four primary elements:

New Hire Contribution = Capability + Context + Connectedness + Drive

Capability is a combination of an individual’s intelligence and skills, including the capacity to develop and improve on these traits. Context is an individual’s understanding of his or her organization, business, industry, etc., based on an accurate education and experience base. Connectedness represents an individual’s internal and external relationships to the organization that are relevant to the business, function, and role of the new hire. Finally Drive, in simple terms, is the employee’s level of pursuit of excellence.

Let’s examine Capability a little more closely. Although individuals are born with a level of innate intelligence and have valuable natural or developed skills, there is substantial room to develop both of these traits through continued development and encouragement. The capacity to develop know-how and skill, therefore, may be just as important, if not more, than an individual’s innate level of both traits.

Context is the variable that may be most often taken for granted, but it is crucial to bringing together the other three in a way that drives significant New Hire Contribution. Understanding the organization means much more than knowing who runs it and what it does. It is a deeper comprehension or mastery of the organization’s mission and goals, the strategy that has been set to get there, the competitive and regulatory landscape, the customers and their needs, the resources available, the business model the firm employs to execute on the strategy, and the firm’s culture and way of doing business and driving change. When employees truly understand the organization, they can act most fully as agents of the organization’s mission and not simply complete tasks assigned to them. With the right Context, employees can step up beyond their defined role, title, age, and experience level to add more value to an organization than originally expected or planned. The period early in an employee’s life cycle with a given organization can be more significant, but the chance for success radically decreases without sufficient context. The key is to provide context that will allow the employee to use his or her capabilities, connections, and drive to deliver the very best possible results.

Experiential understanding includes all of the contextual knowledge gained during a lifetime in and out of the profession. The more an individual understands about the realm in which the organization operates, whether in a certain market, industry, region, and so on, the more value that individual can add to the organization. This is not to say that experiential understanding is necessarily measured in years of life or work experience. We gain experiences and worldly knowledge through research, specialized learning experiences, or, in the modern age, through being a curious individual with an Internet connection.

Our Connectedness in the business environment affects our ability to get things done more quickly and to a higher standard. The personal and professional relationships we have provide us with leverage under certain circumstances, such as when we are looking for a job. According to the US Bureau of Labor Statistics, about 70% of jobs are found though networking.5 The more connected we are (in terms of both number and quality), the better the job search outcomes will be. The same applies in professional endeavors. When a situation arises, a new task is assigned or an unfamiliar request is made, a new hire who has many connections (and understands the relative value and area of subject matter expertise) can reach to his or her network to get perspective and assistance rather than working from scratch to determine the optimal solution. Strategic onboarding can increase the number and quality of connections both within and beyond the organization.

Drive is the combination of ambition, entrepreneurialism, and attachment to the enterprise. Ambition provides the energy for an individual to pursue excellence in everything he or she does. Entrepreneurialism provides the grittiness, the willingness to sacrifice and push and the necessary creativity to create efficient and effective answers. Attachment represents the degree to which the individual cares and is motivated to perform for the organization’s benefit. The greater that each of these factors is for a given new hire, the greater the net new hire contribution over the short, medium, and long terms.

These four variables—Capability, Context, Connectedness, and Drive—together influence the result of the New Hire Contribution (NHC) or productivity. As the preceding equation indicates, we can think of adding up an individual’s unique blend of Capability, Context, Connectedness, and Drive to arrive at his or her potential New Hire Contribution. Conceptually it would even be possible to score an individual in each of these variables on a scale of, let’s say, 1 to 10, and come out with an overall NHC “score.” In this case, a maximum score of 40 (10 + 10 + 10 + 10) would represent the super employee, one who could add the maximum potential value to a given organization. We should note that our equation for New Hire Contribution purposely excludes the issue of resources (e.g., size of team, budget, tools, etc.) made available to an employee. For the purpose of discussing managing new hire potential in the context of onboarding, we treat all things as equal with regard to level of resources.

Mathematically, the lowest possible score would be a 4 using this scale. However, most recruiting organizations screen for individuals who have a minimum level of capability and drive (let’s hope so anyway). Thus, even the most inexperienced of new hires for a moderate position would join the organization with, for discussion sake, an NHC of “10” (4 each for capability and drive, and 1 each for context and connection). Our expectation is that once the individual starts work, the organization can influence all four of these factors to raise the NHC.

Take another example. Perhaps your organization hires an individual with a couple of years of experience in the industry who meets Recruiting’s minimal requirements for capability and drive as discussed. Because the individual comes from the industry, it is reasonable to expect that he or she has some Context and Connectedness (i.e., contacts) that may be valuable in the new position. Together, this may warrant a score of 4 in all four categories, yielding an overall NHC of 16. This represents a 60% increase in new hire contribution from the “base case” inexperienced employee discussed previously. Whether or not the “perfect” NHC score exists (or you have had the great pleasure of working with a new hire who achieves one) is beyond the point of this text, but you can play with this model and think about your existing employees and the candidates in your recruiting pipeline and see how their differences in capability, context, connectedness, and drive result in different NHC scores.

We’ve discussed New Hire Contribution, but how exactly can your onboarding program impact it? Chapter 2 shows that a strategically designed program encompasses a multitude of elements, including engagement and networking, effective training modules for teaching culture and strategy, mentoring programs, early career development programs, and much more. Each of the onboarding program elements acts as a contributing force for at least one, if not several or all, of the four factors that make up NHC. We refer to the combined effects of the onboarding elements together as the Onboarding Multiplier. The equation that follows summarizes these effects.

The Onboarding Margin New Hire Contribution = (Onboarding Multiplier) X (Capability + Context + Connectedness + Drive)

The elements of an onboarding program, represented in the Onboarding Multiplier, therefore, enhance the core variables of New Hire Contribution. Onboarding elements can in fact significantly affect the score an individual would receive in each of the four NHC variables by providing stronger opportunities to develop in each of those areas when compared with a run of the mill or nonexistent onboarding program. Let’s take a look at how the different elements of an onboarding program can affect the NHC. A strategically designed mentoring program that engages new hires from Day One or earlier can pump up all four NHC variables: Capability (mentors often provide informal training and skill development); Context (mentors help ramp up new hires to the organization’s culture, mission, business model, and strategy); Connectedness (mentors often provide networking opportunities to new hires by offering to arrange meetings with individuals within their own network); and Drive (mentors can assist new hires in identifying stretch roles and other opportunities to drive motivation). Formalized networking events, however, may affect on three variables: through networking with more tenured employees a new hire gains more context to the organization’s mission and strategy; networking clearly impacts one’s connectedness; and one may argue that networking can have a positive impact on drive, if a new hire engages with individuals that get him or her more excited about career prospects. As all onboarding elements have varying degrees of impact on the overall NHC, a well-designed diagnostic (as discussed in Chapter 8) will identify for you which elements will ultimately have the highest impact.

Employing basic algebra, what we have now is a way to describe the effect that onboarding programs can have on NHC. Taking together the onboarding elements referenced above, we can speak of a single “onboarding multiplier.”

A successful onboarding program adds value by multiplying the Onboarding Multiplier by the four key variables a new hire brings to the organization. It must be acknowledged that at least some of the employee output variables would develop naturally over time even in the absence of high-quality onboarding. For example, an individual’s contextual knowledge will increase as he or she spends more time at the organization regardless of any formal onboarding program. However, a strategically designed onboarding program will begin to act as a multiplier or accelerator that greatly improves the outcome.

Let’s assign the Onboarding Multiplier a “standard” value of 1. This is the value of a run of the mill onboarding program. Each element of the Onboarding Multiplier, therefore, also has a standard value of one. The better an onboarding program is designed, the greater the value those multiples can achieve. Is it possible to take an average mentoring program and turn it from a 1 into a 50? Probably not. But even a 20% increase in quality (in other words, a multiplier of 1.2), can substantially affect an individual worker’s output because of the multiplying effect of the Onboarding Multiplier.

The Onboarding Multiplier does not always impact positively on an individual’s NHC variables or the overall employee output ranking itself. Poorly designed onboarding programs (or well-designed programs executed poorly) can detract from an individual’s capability, drive, connectedness, or context and in turn decrease the individual’s overall New Hire Contribution. Imagine that a new hire is immediately placed on a long-term and unique project with few other colleagues and no initiatives or programs in place to engage the individual. It would be very difficult for this new hire to develop a connection to, and engagement with, the firm he or she has just joined. This would undoubtedly result in a decrease in connectedness and possibly in drive, leading to an overall reduction in output. If you value the productivity of your new hires, it’s that much more critical to examine your onboarding practices through a strategic and strategic lens to avoid negative results.

Remaking the New Hire Employer–Employee Compact

So far we have made a business case for strategic onboarding by focusing on the direct benefits an onboarding program provides to the enterprise. Yet onboarding offers employees concrete benefits as well. When we look at it from an employee’s perspective, we realize that a solid program holds the potential to fundamentally remake the compact between employees and their organizations. This compact, the mutual agreement between employer and employee, has already changed in recent years—and not necessarily for the better. Employees are now asked to work harder, smarter, longer hours and give up cherished long-term benefits. The promise of “lifetime employment” has also been shattered. Employees today are far less loyal. As one study has shown, younger workers will change jobs an average of ten times before they turn forty.6 Onboarding allows you to remake the compact between employer and employee in a way that makes employees more fulfilled and that allows firms to realize increased engagement, retention, and productivity. We believe that onboarding presents an exciting opportunity for a firm to think differently and make an explicit promise and then deliver more value to the new hire beyond a resume line item and a paycheck.

Onboarding benefits employees in the first instance by giving them the tools they need to succeed and grow into more fulfilling careers. When effectively onboarded, employees gain new skills better and faster, securing their job and job prospect, moving up the ladder, and growing financially at a quicker clip. Doors open as employees’ skills improve and relationships develop, both inside and outside the firm. Employees are able to move more quickly from positions that don’t necessarily excite them to ones that do. If new hires enter a top company in the finance department because of their accounting degrees, onboarding might help them gain confidence that this company will offer a better chance of navigating toward their true aspiration of, say, running a part of the company. It allows them to become aware of the skills they need to develop, provides the network connections they need, communicates an understanding of the overall organization and how it makes money—all this allowing them to make the right choices to take themselves where they want to and have the capability to go.

Beyond providing skills, Strategic Onboarding helps employees by inspiring them and giving them the appropriate sense that they are performing meaningful work. Most workers today want more than a paycheck. They want to be happy at work, realize a great future, and feel connected to something bigger. Onboarding’s strategic piece helps new hires connect their own work with the organization’s larger objectives. If you define your job as a customer service representative in terms of how many calls you take, it can only be so interesting. By contrast, if the CEO gets you excited to be part of an organization whose mission it is to help customers and drive profits, then your job has meaning above and beyond its purely functional elements. You are not just another worker in the factory building; you are the agent of the brand. You become more satisfied with this entry position, and your engagement improves right out of the gate. And if you continue to receive experiences that reinforce the vision and your future, you are far more inclined to stay at the job and work more productively.

We crossed paths with a recent ivy-league finance graduate who, thanks to a poor economy, was working retail for a top fashion brand. She had a job on Madison Avenue, but she was unhappy as a floor salesperson. This woman said she couldn’t imagine ever entering the corporate side from her current position as a clerk in the retail division. She was looking for a better job of any kind. From our perspective, this woman held the potential to become a classic success story—the smart employee who starts on the retail floor and works her way up. Unfortunately, she couldn’t conceive of how her current job folding shirts and straightening the dressing room could ever lead to a fulfilling career with the company. Many customers that she interfaced with were demanding and obnoxious, and nothing about the job stimulated her intellectually. If delivered correctly, onboarding could engage this woman, open her eyes to career paths within the company, and get her excited about the role she plays on the front line delivering the brand to consumers. As part of a strategic program, management could inspire her by connecting her work to the larger mission. It could stimulate her to deliver a superior experience by showing her profiles of people who entered this company at the same very level and today hold senior executive positions in every core function of the enterprise. Would she fully buy in? We can’t tell you for sure, but we can tell you that some numbers of her peers would, and that the outcome would be tremendous for the company.

Let’s look at a contrasting example—that of Apple’s retail division. The tech support personnel at Apple’s retail stores—called “Geniuses”—offer a highly differentiated and (and some say) superior customer experience in support of Apple’s brand and products. Geniuses seem to know almost everything about the products and associated problems, and they patiently and enthusiastically help resolve customer problems, on occasion even going the extra mile and fixing items for free. It is largely seen as a contrast in expectations (both of consumers as well as business students) given the general perception that a tech guru is not likely to be the same kind of person who may hold excellent interpersonal skills and make wise business decisions in real time when interfacing with customers. How do the Geniuses get so good? Exceptional onboarding. From conversations with individual Geniuses, we learned that prospective Geniuses who have proven their technical prowess must first make the grade by working at an Apple store for a month out on the retail floor to get a feel for consumer interaction. Prospective Geniuses are then flown to Apple’s headquarters for a full month of training, all expenses paid. The first two weeks involve intense classroom work, followed by a week of self-study and a week of testing. Upon their return, Geniuses are made to shadow other Geniuses and establish formal relationships with mentors before being allowed to proceed with their jobs. It’s a huge investment for retail, but it produces employees who are unusually passionate about their jobs, expressive of Apple’s brand, and appreciative of Apple’s investment in their success.

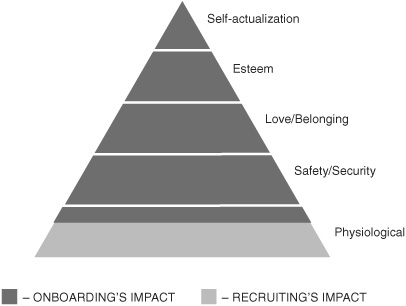

The Needs of a New Hire

Let’s take a more methodical look at employee needs and the ability of strategic onboarding to meet those needs. The psychologist Abraham Maslow described in his 1943 paper, A Theory of Human Motivation, a hierarchy of human needs (Figure 1.3), starting from base physiological needs and extending upward through safety, love/belonging, esteem, and full self-actualization. The overarching premise of the model is that individuals start at the bottom and really only pay attention to the next level of needs (higher up the pyramid) once they satisfy the ones on the current level. Maslow’s hierarchy helps guide our thinking about employees. Corresponding to bottom-level physiological needs are the employee’s need for financial resources in the form of compensation—the paycheck that allows us to eat, live with a roof over our heads, and achieve a lifestyle that increases our chances of attracting a mate. Of course, this is the need that recruiting, not onboarding, fulfills for a new hire. Thanks to a firm’s recruiting function, employees have their most basic physical requirements met; they’re able to survive. But this is where Recruiting’s ability to fill employees’ needs ends.

Once employees enjoy a steady income, they naturally become concerned with keeping it—an imperative that corresponds to “safety” or security on Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. New hires need to feel reassured that their livelihood will remain intact, the company will remain healthy, their function won’t be outsourced, and they possess the basic skills required to remain in the organization. New hires also need to feel like they understand the firm’s culture well enough so that they won’t make any career-limiting gaffes, like ordering a drink at a business lunch (or not ordering a drink), or advocating an idea too stridently. As will be seen in subsequent chapters, onboarding gives employees the skills, knowledge, personal relationships, and cultural awareness to achieve a level of security in an organization.

Figure 1.3 Potential of Recruiting and Onboarding to Satisfy Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs

Onboarding also provides employees with a sense of “fitting in” at work, corresponding to what Maslow sees as the third-level human need for love and belonging. Onboarding’s interpersonal network development element gives employees a head start in making friends and allies within a firm. Onboarding also helps employees build relationships by giving them the skills they need to do their jobs well. When employees perform sooner and at a higher level than their bosses and peers expected—when they stay longer than the average employee and take the company’s mission as their own—their colleagues, bosses, and the company as a whole take notice and begin to “love” them. It may sound strange to speak about love in the context of managing human capital in an organization, but every executive we speak with quickly speaks about the junior employees they have worked with over the years with whom they just “loved” because of their strengths as an employee. Some hiring managers claim—tongue in cheek—that finding an employee you love in this context is as hard or harder than finding romantic love. In a workplace setting, “love” translates into an ability to have open, frank conversations with bosses and peers, among other things. New hires feel comfortable to say what they really think, and as a result, they find themselves pleasantly affirmed, validated, and appreciated for their own unique qualities.

Such validation leads directly to a next level called esteem—self-esteem, achievement, respect of others, respect by others. Thanks to relationships built because of onboarding, and thanks, too, to employees’ abilities to function both at higher levels and as authentic members of a community, new hires are positioned to feel great. If we give people more tools to succeed better early on—if they understand the culture, have the requisite skills, and have a chance to impress others—their sense of self-worth (and therefore satisfaction) will skyrocket. Employees will feel proud to work at their firms and will likely become strong evangelists for corporate and employment brands.

Onboarding’s components that teach strategy also play an important role here. To the extent that companies can change employees’ perceptions of their jobs from a functional description to one that contains a sense of mission that “I am excited to be part of this,” companies will dramatically enhance employee self-esteem. The recruiting process already does try to inspire new hires, but onboarding must reinforce this idea, in ways both large and small, during the first year and beyond. Think, for instance, how uninspiring it is to arrive at a new job only to spend the first day or two filling out forms, completing compliance materials, and taking care of other boring administrative tasks. New hires in this situation take nothing away from that first day that helps them regard the company as the best in the world. These new hires will not feel especially great about themselves (“We are what we do.”), which in turn will affect engagement levels, and ultimately, job performance. With a dynamic strategy in place, we can craft the new hire’s initial entry into the firm to be far more inspirational, leading to higher productivity from Day One, or even earlier.

Once employees feel high self-esteem, they are in a position to satisfy the highest-level need, self-actualization. Strategic onboarding helps further nourish self-actualization in part by providing early career support that maps out fulfilling, enriching careers as well as tools to help get new hires on their way. Onboarding’s strategic immersion and development components again prove helpful, too. As new hires become more connected to what an organization does and its broader mission, they develop a feeling of purpose and direction. They start to equate their own personal success with that of the organization, creating a positive dynamic that benefits all parties to the employment compact.

It’s interesting: Many companies today are guilty not so much of ignoring employees’ needs for self-actualization, but rather of overpromising and underdelivering against those needs. Recruiting machines at large corporations often hype up the sales pitch for these firms, enticing new hires with visions of meaningful, satisfying work that later prove too good to be true. A service company’s recruiting video, for instance, may excessively glamorize lower-level service positions, making the teller position look like mission control in a space shuttle and the customer service position like Mother Teresa. (Yes, videos like this do exist.) This company has probably delivered on the lower four levels of employee need, but the job is still a job, and there’s a great chance that new hires will come away disillusioned from this video. Other companies make similar promises and deliver far less to employees than this company does. At these firms, employees quickly become cynical and unhappy.

Companies with powerful and positive consumer brands need to be especially aware and vigilant on this point (delivering against expectations), because many new employees arrive at their employer only to discover that the consumer brand is at odds with the firm’s employment and operating brand. Apple’s consumer brand is suffused with user friendliness, for instance, whereas Apple’s headquarters and development culture is known to be quite intense. To assure the best, most fulfilling workplace experience for new hires, and maximize productivity gains for the firm, the recruiting engine and ultimately hiring managers need to convey realistic information about the job, the firm’s culture, and the extent to which employees can hope to realize self-actualization as they define it.

Even the best onboarding program will rarely assist the new hire in achieving self-actualization during the first year on the job. But new hires will be on quicker paths to self-actualization, and more importantly, they’ll come to believe in the course of the first year that their new employer can deliver far up the Maslow pyramid. As a result, employees will be more inclined to feel that the firm is the place for them over the short and the long term, leading them to give more of themselves. Managers seeking to affect organizational change thus need to figure out how to help people chart a path toward the achievement of their overall needs. To help an organization move toward success, managers must articulate customized paths toward employee self-fulfillment that take into account the unique strategies, visions, and organizational capacities that individual firms adopt.

Summing Up

Onboarding today remains relatively new, little known, and underappreciated. To help encourage firms to make the investment, this chapter has sought to convince organizational leaders and operational managers that onboarding is well worth a company’s time, energy, and dollars. It has been argued that such programs can deliver astonishing value in an area of the business where none was thought to exist. Onboarding isn’t just about delivering efficiencies in a traditional orientation process; rather, by going well beyond orientation and striving to meet new hires’ needs throughout the entire first year of their tenure, strategic onboarding can deliver clear improvements across a variety of metrics. These improvements add up, measurably affecting firms where it counts—the bottom line.

That’s not to say that onboarding will improve your company’s retention or other metrics by 50% or 60%. Rather, the gains to expect are in the neighborhood of two to six percentage points, say from 10% to 8% or 4%. Yet these gains wind up giving firms a perceptible boost in financial measures such as revenue, cost, net income, or market capitalization—as detailed in an analysis in this chapter’s appendix. They place onboarding on par with lean manufacturing, innovation, focus on core competencies, outsourcing and other progressive disciplines that over the past 20 years have helped companies run better, compete, and create new value. Just as these disciplines have boosted broader economic performance, so too might onboarding. Also consider its prospective importance given that today we are competing on the back of human capital, not manufacturing capital.

In some ways, it makes more sense for firms to invest in onboarding going forward than it does in these other value-creating disciplines. Proficiency at innovation has proved lucrative for many firms, but it’s awfully hard to become the next Apple. With onboarding, you don’t need a lot of new technology. Simply roll up your sleeves and become more thoughtful about the way your firm incorporates its new talent, and you can help your firm uncover vast stores of previously hidden value.

Given all that onboarding has to offer, here is a final argument for the leader who’s still dubious about changing the way his or her firm incorporates new hires: The competition probably is not yet doing onboarding well, so an opportunity exists to create competitive advantage. Firms that act early will hold a unique weapon in the battle for high-potential labor. Prospects are always more inclined to work at a firm that’s regarded as a superior place to build a career, and a strong onboarding program will stimulate that impression by helping new hires build better careers. Firms that hasten to embrace strategic programs will also realize earlier productivity gains, generating profits that they can in turn reinvest to assure even greater value-creation going forward.

We’ve just added up the great value strategic onboarding can deliver, but we have yet to explore exactly what strategic onboarding entails and how the various elements working together can help deliver the Onboarding Margin. This is the work of the next chapter. If you opened this book thinking state-of-the-art onboarding is just a standard orientation made better, perhaps by a new software program, cleaning up an administrative mess, or a few extra hours or days of initial training, then you are in for a pleasant surprise.

Appendix: An Economic Analysis of the Onboarding Margin

We wanted to test widely the economic impact the Onboarding Margin might have on various companies if onboarding was adopted successfully. We created a model based on a conservative set of assumptions, testing across a wide set of companies to measure impact on attrition, productivity, profitability, and ultimately total shareholder return—in the form of market capitalization. Ours is not a perfect analysis, but it displays—albeit directionally—what is at stake for operating entities.

We started with six industries and representative companies from each (relying on publically traded companies for ease of access to necessary data), as follows:

• Aerospace & Defense: Boeing, Lockheed Martin, Honeywell International, Northrop Grumman

• Energy & Utilities: Exxon Mobil, Chevron, Constellation Energy, Halliburton

• Financial Services: Bank of America Corporation, Citigroup, Franklin Resources, Goldman Sachs

• Healthcare: UnitedHealth Group, WellPoint, McKesson, Medtronic, Johnson & Johnson

• Technology & Telecom: Cisco Systems, Google, IBM, AT&T

• Consumer Packaged Goods: PepsiCo, Kraft Foods, Procter & Gamble, Coca-Cola

These companies were all selected for their size and representative nature by someone outside of our Organization Development and Onboarding practice; that way, we could ensure a lack of bias with regard to any knowledge of these companies’ current state of onboarding. All of these companies were treated equally with regard to the assumptions about potential impact, irrespective of any knowledge that we had on the current state of their onboarding efforts. The objective was to build and test a broadly applicable model, not to pass judgment on the performance or impact of any particular company.

Onboarding Margin: Attrition Effects

Our next step was to determine the hypothetical impact suboptimal onboarding might be having today on the overall economic performance of the businesses. We started with the current cost of attrition. To calculate the cost of total attrition for an organization, we applied some common numbers by industry for average attrition levels. Aerospace and Defense, 12%; Energy and Utilities, 15%; Financial Services, 15%; Healthcare, 12%; Technology and Telecom, 15%; Consumer Packaged Goods, 10%. Next we determined the total number of individuals leaving each benchmark company a year. Given the current economic condition at the time of the analysis, we assumed 0% net company growth in revenue and head count. Consequently, we assumed that the number of employees entering a company in a given year was equal to the number of employees leaving.

Next we needed to determine the average cost for a new employee at each company. To do so, we started with the median salary per company. We used external research databases of salaries to find median salary for employees at different levels. Once salaries for each level within a benchmarked company were determined, we removed positions and salaries that were outliers so to avoid skewing results. The median salary by industry was as follows:

• Aerospace & Defense: $75,016

• Energy & Utilities: $81,047

• Financial Services: $75,744

• Healthcare: $69,644

• Technology & Telecom: $80,368

• Consumer Packaged Goods & Retail: $53,410

Although average salary rates can help determine the cost of a new employee, it was necessary to include a factor for recruiting costs. This factor includes HR costs of looking for new employees, temporary replacement fees, headhunters, paying a leaving employee for remaining vacation days, etc. Although many sources cite 1.4 times salary cost as a figure for employee replacement, we applied a more conservative factor of 0.75 times salary per employee.

With these inputs, the following calculation was performed to arrive at the annual cost for the benchmark companies within an industry: (# of employees that attrit) X (average salary) X (recruiting costs factor of 0.75). These numbers were then applied against a ratio for each industry to reflect the fact that the benchmark companies only reflected a percentage of the actual sectors being examined. Once applied to the larger and complete industry as represented by all of the companies in the industries, the total annual cost of attrition—purely for replacement cost purposes—was as follows:

• Aerospace & Defense: $5.8B

• Energy & Utilities: $3.1B

• Financial Services: $90.7B

• Healthcare: $11.3B

• Consumer Packaged Goods & Retail: $2.8B

These are pretty astonishing numbers. Yet we were not finished. Although these figures reflect current attrition rates, we wondered what could happen if onboarding could reasonably help attrition. How much would industries actually save?

To quantify the potential savings of a robust Onboarding program, we assumed that attrition rates would drop to current industry best-in-class standards. Note that we were not pushing the envelope far here. We were not asking for attrition levels to redefine themselves in any seismic way; rather, we were assuming a scenario in which best in class results became the norm. Based on secondary research, we assumed the following best-in-class attrition rates for the following industries:

• Aerospace & Defense: 10% (vs. 12% previously)

• Energy & Utilities: 10% (vs. 15% previously)

• Financial Services: 10% (vs. 15% previously)

• Healthcare: 9% (vs. 12% previously)

• Technology & Telecom: 10% (vs. 15% previously)

• Consumer Packaged Goods & Retail: 8% (vs. 10% previously)

Applying these new best-in-class attrition rates to the same cost of attrition calculations preformed for current attrition rates, we determined that the cost of attrition with a robust Onboarding program would offer significant cost savings. By industry, the cost savings potential was as follows:

• Aerospace & Defense: $973M (total cost of $4.7B vs. $5.8B previously)

• Energy & Utilities: $1.0B (total cost of $2.1B vs. $3.1B previously)

• Financial Services: $30B (total cost of $60.5 vs. $90.7B previously)

• Healthcare: $2.8B (total cost of $8.4B vs. $11.3B previously)

• Technology & Telecom: $2.4B (total cost of $4.9B vs. $7.3B previously)

• Consumer Packaged Goods & Retail: $568M (total cost of $2.3B vs. $2.8B previously)

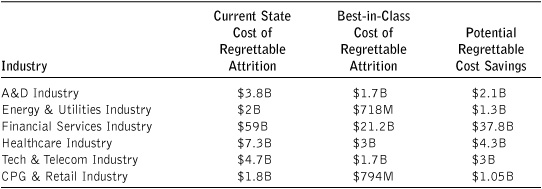

The next thing we looked at was attrition mix—regrettable versus non-regrettable, because as we have discussed, not all attrition is created equal. Although the potential cost savings for lowering general attrition rates through onboarding is compelling, the figure is just that—very general. With this in mind, we set out to determine the cost of “regrettable” and “non-regrettable” attrition under current and best-in-class attrition models. Under current attrition rates, we assumed that 65% of attrition was regrettable (we were sorry to see them leave), and 35% was non-regrettable (we were happy to see them leave). Under this model, the breakdown of regrettable vs. non-regrettable attrition under current conditions was the following:

• Aerospace & Defense: $3.8B regrettable vs. $2B non-regrettable

• Energy & Utilities: $2B regrettable vs. $1.1B non-regrettable

• Financial Services: $59B regrettable vs. $31.8B non-regrettable

• Healthcare: $7.3B regrettable vs. $3.9B non-regrettable

• Technology & Telecom: $4.7 regrettable vs. $2.5B non-regrettable

• Consumer Packaged Goods & Retail: $1.8B regrettable vs. $1B non-regrettable

Having broken down current cost of attrition by regrettable and non-regrettable rates, the next step was to find how these costs would be impacted under a best-in-class attrition mix scenario. We assumed that attrition would shift from a 35% non-regrettable/65% regrettable ratio under the “current model” to a 65% non-regrettable/35% regrettable ratio under a best-in-class model. The results are shown in Table 1.2.

Table 1.2 Cost Savings Attributable to Favorable Attrition Mix

Onboarding Margin: Productivity Effects

Now we wanted to move on to the productivity opportunity. We assumed that 90% of new hires were retained into their second year. Additionally, based on extensive secondary research, we found it reasonable to assume that 25% of retained employees were operating at an average of 50% optimal productivity levels. Although other sources suggest that a far larger percentage of retained new hires operate at lower productivity rates, we selected a lower percentage to arrive at a more conservative calculation. Then we assumed that the remaining 75% of second-year new hires were operating at the maximum productivity level (100%). Again, the idea that this many (75%) new hires are operating at 100% productivity in year two appears conservative by all accounts from our experience or feedback.

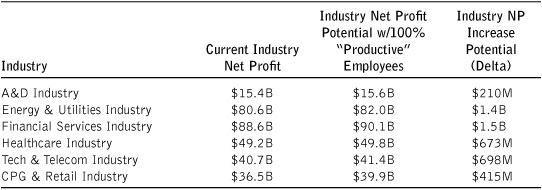

Now comes the thoughtful but tricky part. Because the objective of every employee is to help produce company profit, we took the profit of each benchmark company and calculated the contribution to profit for the average employee (using total head count). Then we calculated the prospective impact of each of the retained second-year employees (25% of the 90%) who were operating at less than 100% productivity, and imagined what would happen if they had actually been operating at 100% productivity. This bump added to the current net profit of a company yields the potential net profit bump. When applied to at the industry level, the net profit increase potential is significant (Table 1.3).

Table 1.3 Profit Potential Attributable to Higher Productivity Levels

Onboarding Margin: Combined Effects of Attrition and Productivity

To make this analysis even more fun, we looked to see what these combined numbers (attrition impact and productivity impact) would yield to investors in terms of market value (as measured by market capitalization). We applied traditional industry-specific stock price to earnings ratios (P/E) ratios as compiled by NYU’s Stern Business School as follows: Aerospace and Defense 14.6; Energy and Utilities 24.51; Financial Services 13.08; Healthcare 28.36; Technology and Telecom 33.32; and Consumer Packaged Goods 23.50. Based on these historical P/E ratios, the impact to average stock price gain was as follows:

• Aerospace & Defense: +15% or +$34B in additional market cap for the sector

• Energy & Utilities: +3% or +$65B in additional market cap for the sector

• Financial Services: +44% or +$514B in additional market cap for the sector

• Healthcare: +22% or $278B in additional market cap for the sector

• Technology & Telecom: +23% or $280B in additional market cap for the sector

• Consumer Packaged Goods & Retail: +4% or $34B in additional market cap for the sector

Recognizing that we did not have a perfect sample by any means and that the analysis was applied to a given year (and that profit changes year to year for a whole host of reasons), we simplified further and determined an average prospective impact of 19% (the simple average of the prospective six rates of stock price improvements noted). Just to be on the safe side, we cut this answer in half, bringing us down to ~9%. Then we did the same again—knocking this number in half, bringing it down to 4.5%. We asked respected HR leaders from large corporations what would happen to their career if they took an action that resulted in their company’s total value going up by 4.5%. (Don’t forget, these market caps are really large numbers.) Each and every person offered the same response: A wonderfully big smile.

Cautionary Comments

• Please note that the calculations for a given industry are not numbers with which you should run to your colleagues. We feel far more comfortable talking about the average impact across industries than we do speaking about impact for a given industry—given all of the year-to-year variables at play.

• Our analysis on market cap excluded the impact of improvement in time to productivity (Gain 1) and raising the overall average level of productivity (Gain 2) of your new hires, which is a huge part of the Onboarding Margin! Why did we exclude these two very large factors? Because the numbers were getting big enough without it, and we simply felt far more comfortable making a smaller claim.

• This entire analysis was done not with precision in mind, but rather to determine with directional accuracy whether or not the Onboarding Margin was worthy of our, and your, attention. We think the results speak for themselves.

Notes

1. In modeling total industry impact, we treated the sum of the benchmark companies’ net profits as a percentage of the total net profit of an industry (Sources: Yahoo Finance Industry Browser and NYU’s Stern Business School data). As a result, the benchmarks’ net profit was a percentage of total industry net profit:

• Aerospace & Defense: 64%

• Energy & Utilities: 62%

• Financial Services: 5%

• Healthcare: 18%

• Technology & Telecom: 87%

• Consumer Packaged Goods & Retail: 75%

This percentage was applied as a ratio to the sum of all model inputs for benchmark companies in a given industry to provide total industry calculations. All subsequent industry inputs/figures are based on this ratio and reflect the modeled total industry figures.

2. We used 2008 for all company data in the analysis.