8

GETTING STARTED:

CONDUCTING

A PROGRAM DIAGNOSTIC

Most organizations have a distinct set of onboarding needs. Some battle high attrition or low time-to-productivity, whereas others need to ensure effective knowledge transfer between legacy and new employees. Still other organizations are spending way too much on onboarding (or more specifically, the front-end administrative piece of onboarding) and need to make processes more efficient to wring cost out of the system (see our Onboarding Objectives table in Chapter 1). Because every organization’s circumstances and goals are different, it’s important when designing an onboarding program to catalogue what a company currently does to orient employees and assess the best opportunities for improvement. Unfortunately, the vast majority of organizations do not devote enough time to taking stock of problems and opportunities. As a result, they either fix the least important problems, or they come up with improper solutions to the right problems. Their redesigned programs fail to meet expectations, and they wind up with poor returns on investment and decreased organizational commitment to address onboarding as a performance improvement opportunity.

To succeed with onboarding, organizations should begin the design process with a diagnostic assessment that identifies the main problems onboarding can address, the size of the opportunities, the root causes behind the problems, and the most practicable solutions given the organization’s unique circumstances, operating conditions, and constraints. Performing this assessment not only helps an organization arrive at the best result; it also helps designers sell the program into key stakeholders in an organization. The exercise also allows you to objectively determine if onboarding renewal merits investment in the first place. (We have found some cases in which performance was strong and the business case for additional investment weak.) After exploring in more detail why the diagnostic phase is so important, this chapter offers a rigorous four-step process for measuring the opportunity, determining a program’s highest value improvement areas, understanding the root causes and focus areas, and beginning to galvanize stakeholders behind wide-reaching, systemic change.

Don’t Skip the Diagnostic!

When designing an onboarding program, many companies feel an impulse to skip the diagnostic process and put something in place that has worked elsewhere. They want that silver bullet answer—the all-powerful set of “best practices”—and see no need to spend valuable resources on a drawn-out analysis of their needs. Yet rushing to embrace a best practice without taking the time to determine its suitability to your company is a horrible idea. The ancient Greek phrase “Know Thyself” inscribed at the Temple of Apollo at Delphi guides us not merely to success in life, but in onboarding, too.

The rush toward best practices has been fed in recent years by onboarding’s emergence as a topic in the human capital community and press. Articles advising HR specialists how to jump on the onboarding bandwagon often appear in online communities and blogs. A few onboarding conferences have emerged over the past few years. At these events, discussion threads and interest areas commonly center on questions such as, “What best practices do you employ?” and “How do you convince management that this is important?” We know from reviewing these articles and speaking with publishers of this material that way too little analysis goes into determining which practices become “best practices.” We usually find that most of these supposed “best practices” are tactics that sound attractive but have not been assessed for their efficacy. These might better be considered “progressive practices.” One recent Wall Street Journal article reduced the process of “acclimating newcomers” to a few easy tips, such as “make space,” “find face time,” “inform your staff,” and “set goals.”1 Taking such an article at face value, it is easy to see how managers new to onboarding might accord the discipline a limited scope and regard starting a program as simply a process of collecting and deploying what others have done.

A best practice only helps if it matches your company’s unique circumstances and objectives. Under different conditions, a best practice developed by another company could prove useless, and worse yet, a drain of valuable resources. Many want to copy what Apple does, but that technology firm possesses skills, competencies, culture, and objectives that most other firms do not. We have to obtain their skills and competencies and match their objectives if we hope to adopt a behavior or technique of theirs with any success. As part of a thorough diagnostic process, we need to evaluate whether the variables at play in other, benchmark organizations resemble ours closely enough to appropriate their best practices. If not, then we need to determine whether we can take an existing best practice and modify it to fit our actual culture, operating conditions, and skill sets.

A proper diagnostic analysis helps us to arrive at the right priorities. Most companies have limited budgets for onboarding, and better onboarding could potentially address a wide variety of business issues and objectives. We beg you, as practitioners in the field, to be intensely strategic in devising your program objectives. You can design a program that is well run, appreciated, and recognized but that does not deliver appreciably on any defined onboarding goals. A strong diagnostic phase allows companies to go beyond just offering new hires an “enhanced and cool experience” and devise a combination of program elements that creates maximum value.

Apple does not follow blindly what other firms are doing when it comes to onboarding. As we’ve seen, the firm has gained notoriety around the Web for greeting new hires with an exciting, high-concept welcome packet. In incorporating this tool into their onboarding, the firm did more than give new hires an amazing experience. It devised this tool to teach new hires about the brand, and specifically, about the kind of experience the firm wanted new hires to provide its customers. Apple’s welcome packet supported a key business strategy: the pursuit of customer centricity. Another firm might pursue an entirely different strategic orientation, which would lend itself to different tools and a different message. If General Motors places strategic emphasis on building high-quality, durable products, its onboarding packet might be, say, constructed of a durable material. The company could then go on to express the importance of durability, and even link the ideas of building durable vehicles and durable careers to its objective of regaining industry leadership. Or maybe it wouldn’t have even offered a welcome packet and instead chosen to invest its greater onboarding budget in a higher-impact area identified as critical in the diagnostic. In the vast majority of our first meetings with prospective clients, we encounter designers at the earliest stages of a renewal effort who come primed with action items spawned from reading about other companies’ tactics.

Taking time to take stock when designing an onboarding program produces better onboarding because it allows firms to consider solutions keyed not merely to the opportunities and problems at hand, but to the underlying causes of these problems. As part of a strong diagnostic process, onboarding designers determine the root causes of problems by conducting an analysis that correlates experiences, existing tools, programs, and processes with particular outcomes. The designer might ask: Which experiences and processes of ours have resulted in this level of productivity for a certain category of hire? In another case, a firm might determine that a large majority of new hires possess a very limited network after 6 months of employment. The diagnostic process might reveal that this is because the company quickly deploys new hires on remote tasks and does not provide them with any real means to build relationships within the company. The designers of an onboarding program could then incorporate solutions that address new hires’ lack of proper social exposure and relationship-building forums.

In many cases, companies can detect specific underlying causes behind a particular problem rather than the sort of generic causes implied by a knee-jerk focus on “best practices.” As we saw in Chapter 4, one large client of ours was puzzled that their young hires were leaving after a year. The root cause was quite specific—many recruits at the company had to relocate to the corporate headquarters, and too many found it hard to fit in culturally and find peers with common interests in the new city. One solution was to coordinate with other big employers in the region to help new hires establish social relations and also to invest in affinity groups that might help new hire segments feel more connected.

Think, too, of the new hire at a tech company we described in Chapter 3, the one who had a really good idea yet committed a faux pas in sharing it publicly. The problem in this instance was clear, but not the underlying cause. The temptation was to pin the blame on this employee for “not getting” the culture, whereas in truth this new hire was a smart person who erred because her prior employer had established a culture of public debate and had not established propriety around ideas. In such a situation, a diagnostic process might uncover three things: first, a frustratingly high failure rate of experienced new hires (an outcome); second, an organizational need to bring in a large number of experienced managers given important growth initiatives (an organizational objective); and third, exit interviews and job performance reviews indicating that, above all else, many failures centered around not learning the culture soon and well enough (a root cause).

This outcome, objective, and root cause analysis would enable program designers to arrive at appropriate solutions. One solution might include a longer cultural orientation (using techniques that fit the business processes and rhythm of the company), a centralized oversight group that actively monitors new hire acclimation at key determined milestones, and quick education and instruction for hiring managers and peers on the problem’s impact and nature. With this last piece in place, existing employees might prove less inclined to write off an experienced new hire as “disappointing” or “hopeless,” and more energized to help the new hire adapt to the organization’s unique mix of performance values. All three pieces of this prescription should be implemented in a gradual, systemic fashion—baked right into the organization’s processes. Although we’re not discussing yet the process of specifying these design attributes (we are still in the diagnostic phase), it is important to remain aware of them. The diagnostic phase includes assessment of current systems that contribute to current problems and can later be affected to make the program systemic and therefore effective.

Beyond helping organizations craft an onboarding program that applies real solutions to material issues, the diagnostic phase helps change agents sell in the program to diverse stakeholders. Performing an initial analysis of a firm’s current challenges and opportunities provides HR specialists with data they need to drive change, including quantification of the size of the challenge and the size of the prize. The process of obtaining information during a diagnostic phase involves consultation with functional and business unit leaders, which in turn enables their enthusiasm down the line.

Performing a diagnostic analysis provides the onboarding change agent with a baseline against which to measure progress—essential for obtaining buy-in for ongoing investment. Development of a complete onboarding solution cannot happen at one pass; typically it requires a staged implementation. To obtain permission (and budget) to progress to the next stages, change agents need to show the great distance the firm has traveled thanks to onboarding relative to an initial position. And if onboarding is not bringing progress, simply knowing as much empowers you to revisit your onboarding design and figure out where it is going wrong. You need to activate a set of metrics during this diagnostic phase and establish a very clear baseline. As discussed in the last chapter, we recommend that these baseline measures capture numerous inputs (satisfaction levels, retention rates, etc.) for the appropriate segments of your new hire population (by level, business unit, race, gender, etc.) and from the perspective of both new hires and hiring managers.

To understand just how helpful information gleaned during the diagnostic can be in assuring both intelligent design and institutional acceptance, consider the following scenario involving a national health care firm with which we’ve worked. In discussions with the company, we discovered that attrition for the commercial side of their business—the sales and customer service departments—was slightly better than the industry average of 12%. Initial management commentary around discussion of attrition amounted to, “We do well here—just look at the industry average.” Digging deeper, we started to discover some very interesting nuances. First, the firm experienced great regional disparity in attrition. Some regions experienced 4% attrition, whereas some were at 22%. That suggested that some regions were doing an exceptional job and some a poor job at onboarding new employees. When we examined the picture closer, we also discovered that the region that had the highest attrition was the same region of the country that was experiencing the highest rate of unemployment (at the time, 2008, the national economy was in recession). And here’s the real kicker: The highest three attrition regions were also the ones experiencing the greatest customer turnover. Not only was attrition costing the company in labor expense, but it was also costing the company in customers and revenue.

Additional analysis revealed that customers’ frustration with service personnel turnover was contributing to account churn. Moreover, effective practices in certain regions had cropped up, and these could be applied to high-attrition regions without much problem or cost (e.g., transferring the tools and techniques and a little education for the challenged managers). All of a sudden, what had started out as a “feel good” HR initiative got the attention of the CFO and the EVP of sales and became a critical mission to improve revenue and control costs during a prolonged recession.

Now imagine if the HR leader had not conducted this deeper analysis but simply brought forward some generic onboarding improvement practices to these same departments after attending an onboarding conference and learning about best practices. If this HR leader approached the head of sales and asked him or her to implement time consuming and possibly expensive new onboarding programs, the head of sales would likely have shown little interest; after all, he or she is way too busy contending with declining sales in a very challenging environment. Selling-in an onboarding program involves answering the question, “What’s in it for me (the “wiff’em”). By performing a thorough diagnostic up front, onboarding designers can identify areas of great opportunity and develop the hard-edged business case that serious organizations require to drive wide-ranging change. And if you cannot build a real case for onboarding after a diagnostic process, then you should not be doing it.

Conducting a System Diagnostic

In our work with leading companies, we’ve developed a four-step process for conducting a diagnostic evaluation of a firm’s onboarding efforts. The four steps are:

1. Internal discovery

2. External benchmarking

3. Opportunity identification

4. Obtaining organizational validation and buy-in

In running through these steps, you need to take a long-term view, starting at the hour of the candidates’ acceptance of your job offer and running through the greater of the new hires’ first year employment or a complete business cycle for your business. You also need to assess all four pillars of the onboarding framework, as well as the administrative and governance resources available to support onboarding. You need to evaluate not only the designed and formal program elements of onboarding, but also the entire range of experiences that the new hire and new hire managers have. Finally, we recommend that you benchmark against best-in-class and key competitors (either industry competitors and/or regional employers that compete for your labor talent, regardless of industry), which helps in evaluating your performance relative to critical benchmarks.

We now take a closer look at each of the four steps in turn. Although we’ll present the diagnostic phase here as a neat linear process, in practice it can unfold in a far more fluid and uneven fashion. The diagnostic can also be performed in a way that does not result in a bogged down “analysis—paralysis” exercise. Internal discovery will sometimes yield intuitive knowledge of the root causes before the formal analysis of the data. More generally, diagnosis has an iterative or circular character, unfolding gradually and on an ongoing basis. What follows is best regarded as a model of a proper diagnostic process rather than as an iron-clad depiction of what the diagnostic phase will look like for your organization.

Internal discovery

As part of internal discovery, members of an onboarding redesign team should do two things: Assess the current state of the program and identify the organization’s actual greatest needs so as to prioritize key onboarding opportunities.

Understanding the current system activities, tools, and resources that exist for new hires in their first year helps us diagnose the root causes of program underperformance as well as dissatisfaction among new hires and managers. As the diagnostic process unfolds, it also allows you to compare what you have with best-in-class and competitor programs, and later on, to measure your own progress against the baseline. Some organizations have pre-existing process flows, checklists, and new hire guidebooks that outline the program’s current state. Others need to go through the process of mapping out the current state to develop an understanding of all the touch-points and activities that exist as new hires go from offer acceptance to orientation and then into their business unit or function. Put differently, these firms need to understand all the critical “firsts” that do so much to shape new hires’ impressions of their new employment.

• First administrative problem

• First on-the-job mistake when no one notices

• First on-the-job mistake when peers notice

• First on-the-job mistake when the boss notices

• First personality conflict with a member of the team

• First time having a conflict with a supervisor

• First time the new hire calls in sick

• First time an outsider asks the new hire who he or she works for (Remember how important esteem is according to Maslow?)

• First personal victory

• First team victory

• First time new hire gets recognition or fails to get recognition

• First time the new hire faces a situation where he or she didn’t know the answer

• First conflict between the new hire’s two separate reporting lines (e.g., functional and business unit)

• First company-sponsored social event

• First time closing on a sale

• First uncomfortable encounter

• First time the new hire is presented with gossip about his supervisor

• First time the new hire commits an ethical violation

• First time the new hire witnesses an ethical lapse

• The first time the new hire presents the company’s value proposition to a customer

• The first time the new hire speaks at a meeting

• The first time the new hire leads a meeting

• The first stretch assignment for the new hire

• First time witness to a company layoff

• First time doing work unsupervised

• First time having to sell an idea to colleagues

• And so on

Developing a process flow or activity diagram is often the best means of taking stock of the system’s current state and the business processes central to a new hire’s experience. In the activity diagram, we can outline the key process owners that support new hires at each step. A diagram like this helps the design team define roles, responsibilities, and needed process-level changes once the enhanced program is designed.

As you assess a program’s current state, it is helpful to gather information about how much the company currently spends to onboard on an annualized basis. This helps you identify opportunities for cost savings, places where your company is currently under-investing, and the appropriate ways to prioritize so as to achieve an optimum return on investment.

Once you know what your program’s current state entails, you need to assess how well your current program activities, tools, and resources meet the needs of new hires, managers, and the organization as a whole. Here the point is not merely to look for program elements that are failing to deliver, but also program elements that are working well. Identifying internal pockets of “best practices” can prove extremely helpful in many situations, since we can often find ways to leverage these best practices for use within the firm as a whole. Just as with external benchmarking, however, you should evaluate each internal best practice to make sure that it fits the needs and circumstances of diverse corners of the business. Here are some common sources of data to consider when performing an internal analysis.

Common Diagnostic Data Elements

• Census of current employee base

• Census of recent new hire activity (e.g., three-year history)

• Attrition data

• Promotion performance

• Projections of new hire needs (numbers and special skills or other organizational development needs, such as ramp up requirements to support growth areas)

• New hire performance reports

• New hire ands new hire manager satisfaction reports

• Job offer acceptance rates

• Results from any “engagement level” studies that may exist

• Exit interviews

• Results from any recent hire focus groups or surveys

• Other data requirements to be determined at outset of project

• Fresh surveys, focus groups, new hire manager interviews

• Online community chatter (e.g., LinkedIn, Facebook groups, R&D communities)

Onboarding designers need to conduct internal interviews with key corporate, business unit, and functional executives. It’s important to interview these individuals to understand better the primary strategic initiatives and what they most require out of the new crop of talent. By interviewing these leaders, you will not only learn about key business and human capital priorities that should be a focal point for your design, but you will also have the chance to win over these leaders to support the effort with the resources necessary to build a program that can deliver against these needs.

Of course, you hire new people in the first place because managers need to accomplish certain goals and they believe their current resources are not sufficient. These hiring managers are the most important stakeholders, and you need to determine how they think new hires are falling short. These interviews need to be exploratory. They need to not only cover satisfaction levels and ideas for improving the onboarding system but they should also produce:

• An outline of hiring managers’ own business objectives. It’s important to understand these not simply as line items; rather you need to know the nature of the challenges that hiring managers tackle. You also need to explore how managers believe current entrants are falling short and how they could be better equipped.

• An overview of the administrative and business processes with which the new hires and their managers have contact. This will help you understand the challenges of being successful as a new hire as well as the systemic elements of business operations you need to leverage in the redesign effort.

In addition to conducting interviews, we also recommend conducting surveys with hiring managers and recent new hires so that you can quantify your findings. Later on, you can then use these numbers as a baseline against which to measure the impact of your enhanced onboarding program.

Ultimately, organizational needs tell us what specific goals our enhanced program must support. One company we worked with—an electric utility—was expecting 40% of its current workforce to retire within 10 years. This was a very scary scenario considering how much technical know-how this retiring base represented. The company wanted to ensure that company culture, performance values, know-how, and skills survived the transition from legacy to new employees. To service this need, the enhanced onboarding program incorporated two key components: (1) an increased number of opportunities for new hires to build relationships with experienced employees; and (2) a knowledge transfer program enabling these company veterans to impart their accumulated know-how on a formal basis throughout the entirety of the first year. Another company forecasted a 200% increase in employees over the next five years in a rapidly expanding business unit. Here the program redesign focused on educating the new hires on the underlying strategy associated with the growth, the demands that the growth was putting on the business, and the skills necessary to meet those growth demands. All of this was achieved by segmenting new hires into the key areas of intended functional and business growth.

As far as new-hire needs go, many organizations pursuing major program redesign efforts lack sufficient onboarding surveys in place to help guide the redesign effort. Ideally, you would query new hires and hiring managers at different points in their tenure with the company, most likely the 30-, 60-, 180-, 270-, and 365-day marks. When setting survey points, consider time periods that recognize completed business cycles and natural anniversary milestones. You can also brand surveys to associate them with formal phases designated for your onboarding program. Surveys need to include demographic questions (e.g., queries about gender, race, previous work experience, new hire level, function, business unit, etc.) or they otherwise need to correlate with respondent data from centralized human capital information systems. This information will allow you to segment out responses into distinct groups of new hires, providing necessary instruction on how to customize your solution.

Think carefully about which demographic components to include, as this helps determine the quality of your insight and associated program customization. In general, a sampling approach will suffice to get the job done. However, you should consider the brand value of engaging all new hires in the survey activity. If the surveys are designed to speak from the perspective of the new hire and hiring managers, you get an additional benefit—a chance to convey to new hires that your firm cares about their success and takes seriously its role in assuring it. This is a message every new hire and hiring manager deserves to receive.

In evaluating an existing program’s performance, the onboarding design team should also consider how far the program compares with state-of-the-art program characteristics described in Chapter 2. Does the existing program offer tools, experiences, and support in all four pillars over the first year? Are these tools customized to the needs of key new hire groups? Are the key stakeholders in the program participating enthusiastically? On an even greater level of detail, do program elements incorporate the Best Principles described in Chapters 3 through 6?

External benchmarking

Once your organization has assessed its onboarding program’s current state, the next step is to catalogue the program elements and techniques deployed by leading onboarding programs and that of your competition. Again, members of your onboarding redesign team should resist the urge to simply expropriate “best practices” without further analysis. When looking at a specific best practice, your team needs to try to understand what is behind the practice—the root causes that the company was trying to address as well as how the best practice related to the firm’s unique strategic objectives. Finally, your onboarding design team needs to consider best practices and comparative performance metrics through the lens of your own firm to determine if they fit strategic needs and organizational constraints.

Depending upon program objectives, you might also want to evaluate onboarding programs at your chief labor competitors in the recruiting marketplace, typically leading employers in your region(s) or leading employers in your company’s key functions (e.g., the leading companies who recruit product marketing talent if you are a consumer product company). Properly executed, onboarding can distinguish a firm in the eyes of new hires and provide competitive advantage in recruiting this top talent. Speaking with transfer employees from other peer organizations is a great place to start. Some companies also choose to conduct highly detailed peer benchmarking analyses to develop a clear differentiation strategy.

Suppose you represent Caterpillar and you are seeking engineering talent that can enable you to design a whole new tractor that is less costly or that uses hybrid technology. In deciding which companies to benchmark against for recruitment purposes, you might consider Toyota or other companies looking to bring hybrid technologies, as well as other leading engineering organizations like Lockheed Martin, GE, Intel, or Google. Similarly, if you’re trying to bring in top MBAs, you might want to look at how consulting firms, leading marketing companies, and top investment banks are approaching onboarding, since these are your prime competitors for talent. If you are in an industry in which your corporation hires regional talent, then you need to look at who else is competing for that same talent, including smaller, regional firms that at first glance would seem to be in a different league than your own.

Opportunity identification

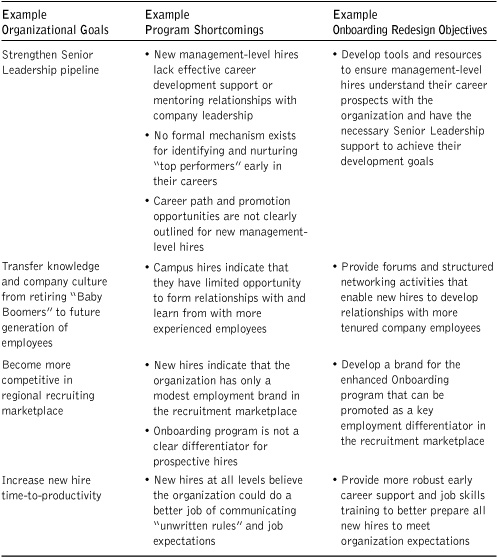

With a good sense of best practices and competitor practices in hand, we now need to analyze the data so as to identify the most important opportunities and come up with recommendations. This part of the process has several steps. First, you should conduct a quantitative analysis of the gap, if any, between your current performance and both your desired performance and external benchmarks. Such analysis should be done for specific geographies, business units, and functions; that way, you will understand the diverging needs and performance levels of different parts of the organization. You will also be able to identify areas across the organization that require greater investment and prioritization. You might even wind up deciding to focus on only one part or cross-section of the organization (for instance, one business function) so as to realize the most business impact. Once you have determined where the gaps are and their size, you should determine the root causes behind these gaps. This in turn leads us to determine where the opportunities lie for improving the onboarding program. Table 8.1 provides a sample framework for identifying program objectives.

Table 8.1 Sample Framework for Identifying Program Objectives

Some of the opportunities you choose to address might have originated from the internal and external best practices uncovered during the prior research phases. Others will have emerged during the course of internal discussions that are not in practice elsewhere. You will need to decide decide which of these the company might plausibly (and profitably) apply throughout the organization. It is important to determine investment priorities, balancing the potential impact with the cost or degree of difficulty in implementation. You should also consider which opportunities might lend themselves to early wins, since these can help to build or gain momentum and thus make buy-in for later phases more likely.

In evaluating possible opportunities, team members should take care to identify operating and business model constraints that limit an onboarding program’s shape or scope. Constraints are helpful since they focus the design process; it is just as important to know what cannot be changed in implementing a new program as it is to know what can or should change. A new onboarding program needs to challenge some organizational assumptions, but clearly some things will remain untouchable.

One financial services firm we have worked with realized it had two constraints as it went about re-defining its onboarding program: It knew that company field representatives would remain in the field; and it knew that growth opportunities for employees would remain limited given the fairly flat organization required by the firm’s business model. Recognizing that the firm had few sales management positions, and that most new hires therefore faced limited long-term career prospects of upward mobility and increasing responsibility with the firm, this company could focus on offering most new hires career training and networking as a part of onboarding. Meeting other sales personnel in the company who have had long, prosperous careers without moving into “management,” and gaining access to the communities they would serve, new hires could understand and feel better about their careers while simultaneously beginning to build relationships that could turn into future sales prospects.

Organizational validation and buy-in

Even as your redesign team tries to diagnose problems and come up with possible onboarding solutions, you should begin the work of selling the rest of the organization on onboarding. The earlier you can get leadership, stakeholders, and broader system participants to buy in, the more support you will obtain for implementing the kind of broad change that a strategic onboarding program requires. We strongly recommend engaging key stakeholders from the start of your process. Enable them to evaluate the current state of onboarding, educate them on the potential and prospect of the Onboarding Margin and the typical objectives of onboarding programs, allow them to participate in hypothesis generation, and encourage them to set forth possible improvement opportunities. That way, they will enjoy more ownership over solutions and be able to articulate in a compelling way the key changes that will emerge from onboarding redesign. Focus especially on convincing stakeholders who feel threatened by an onboarding redesign, since these individuals are those most likely to resist meaningful change.

Taking Shortcuts ... and Starting Off Right

The preceding model represents what we regard as the best way to pursue a rigorous diagnostic process. If you lack the resources to pursue a process as involved as this, we would recommend the following shortcut (although recognize that it is a compromise). Find an appropriate group of representative stakeholders, educate them on onboarding, and instruct them to develop a set of hypotheses about the opportunities, problems, and root causes surrounding onboarding. Validate these hypotheses by testing on a spot basis. Even better, you can supplement these efforts by cherry-picking pieces of the above diagnostic approach that fit your resource levels, time frame, and circumstances.

This is a less rigorous approach, but it can certainly produce an excellent result. In any case, it is far better than skipping the diagnostic. If your initial analysis yields results that inspire a high level of confidence, then you are all set. If you remain unsure as to the proper course, then you should pursue the deeper analysis we have outlined.

We recommend that all firms perform this simpler, initial exercise before proceeding to the main diagnostic process, as it will help target the in-depth analysis. If you are tempted to forego the longer process even though your firm has allocated adequate resources for a diagnostic phase, you should bear in mind that the small group of stakeholders you have initially assembled might well get it wrong. In marketing, companies learn a lot from proper market research, even though they feel from the outset that they possess an intuitive grasp of consumers. Top tier marketing companies know that relying less on intuition and more on customer insights makes all the difference in driving results that lead to industry leadership. The same holds true here. If you can afford the research, you’re better off avoiding the risk that you’ve missed something big or wasted money on the basis of a false assumption.

Summing Up

Before your firm can hope to unveil a state-of-the-art onboarding program, it must take care to gain organizational self-awareness. Do not just grasp at the onboarding “best practices” you read about online or in trade journals. Kick off your onboarding redesign process with a rigorous diagnostic phase that catalogues the onboarding measures currently in place, compares them with those at competitor and best-in-class firms, and identifies realistic opportunities that get at the root causes of problems. Pursued with integrity, the diagnostic phase can help focus a program around a few key objectives among the many that onboarding can viably help you meet. A diagnostic phase can also serve as a fulcrum for beginning to generate buy in and support from stakeholders across the organization.

Once your redesign group has settled on a few key opportunities to pursue with onboarding, you are likely to feel a sense of excitement and momentum around the program you plan to develop. It is tempting to jump right in and start putting programs in place. That would be a mistake. Given how all-encompassing a truly systemic program is, it is vital that you take the time to develop a highly detailed blueprint of what your new onboarding program will look like as it is rolled out over multiple phases. You cannot just put tactics in place haphazardly; you need to create a plan, just like an architect does when constructing a skyscraper. The next and final chapter shows you how to create a compelling onboarding blueprint and then begin the process of transforming your organization.