Main purpose: To comprehend sustainability as a concept: models, definitions, its relationship to capitalism, and its evolution.

Objectives: After reading this chapter, you should be able to do the following:

- • Recognize that companies are rethinking capitalism to be inclusive of the concepts of sustainability and stakeholders.

- • Clarify the dimensions of sustainability and the role of stakeholders.

- • Identify events that helped to shape the concept of sustainability over the years.

- • Compare and interpret various models used to represent sustainability.

The purpose of any company should be to make people’s lives better. Otherwise, it shouldn’t exist.

—Ford Motor Company, Letter from William Clay Ford, Jr. Executive Chairman Jim Hackett, President and Chief Executive Officer

Rethinking Capitalism: Sustainability and Stakeholders

We are living in exciting times as we move forward to clean up our planet and make it a better place for everyone to live. No doubt we face challenges, but as we work together to share knowledge and resources, our journey will be made easier. Our journey is one of sustainability, not sustainability as a final destination or as an afterthought, but rather sustainability as an integrated and innovative approach to the way we conduct business, referred to as sustainable capitalism or sustainable business. To begin this journey, let’s review a few basic characteristics of these two concepts: capitalism and sustainability. We will then be in a position to discuss how a capitalistic system might be adjusted to serve society’s needs and expectations in a more sustainable manner.

Capitalism

A capitalistic economy generally has the following characteristics:

- • Private ownership of most resources through shareholder ownership;

- • Competitive markets providing high-quality goods and services based on supply and demand;

- • Low amount of government interference and regulation;

- • Individuals working to create wealth in their own self-interest; and

- • Growth and expansion through reinvestment of profits.

Sustainability

These characteristics of capitalism worked well in a very different era: one of plentiful natural resources and fewer people. However, today’s capitalism needs to address societal concerns, such as climate change; air and water quality; land contamination and reclamation; scare resources for a growing population; harmful working conditions; and equal opportunity regardless of race, religion, or gender. Self-interest and low government regulation do not address these concerns well.

The capitalism of today needs to fit within today’s context: one that recognizes the expectations of all stakeholders affected by a company’s activities, not just the shareholders (owners). As well, companies are expected to carry out their operations while respecting their employees, customers, and communities. At the same time, they should produce products and services efficiently to conserve resources and lessen their impacts on the environment. Because the wealth in large corporations is often greater than the economies of small countries, businesses should be expected to use that wealth to solve society’s problems and provide a higher quality of life for everyone.

To address society’s problems, companies of today are integrating environmental and social issues into their operations to become more sustainable. A sustainable business is cognizant that a healthy environment and prosperous communities lead to a more stable and resilient world for current and future generations. Sustainability considers three dimensions that strive to include everyone:

- • economic (products and services are provided profitably);

- • social (all members of society share the wealth and enjoy a high quality of life);

- • environment (economic and social activities should leave the planet with diverse, plentiful resources for the use by, and enjoyment of, current and future generations).

These three dimensions of sustainability are also known as the 3Ps of profits, planet, and people. Considering all stakeholders, sustainable businesses produce profits as if the impact on the planet and people is important as well. Even though other models of sustainability have appeared over the years, we will use this original depiction of sustainability, still very popular today, to contemplate how capitalism can integrate sustainability into business operations (Figure 1.1).

Figure 1. Sustainability Venn diagram model

Source: Based on Sadler (1990)

Sustainable capitalism assumes a higher purpose than just making profits. That is the reason some of the more recent models of sustainability have substituted the term prosperity for profits. Prosperity broadens the purpose of a business to benefit all members of society, not just maximizing value for the shareholders. The purpose of our economic system, and thus our businesses, should be creating value for all members of society not maximizing value for just one type of member of our society: those fortunate enough to hold ownership in our corporations through their stockholdings.

Sustainability in Action: Philips and the Circular Economy

It is important to disrupt your business before someone else does. At Philips, we have started the process of fundamentally redesigning our business and our end-to-end value chains.

—Frans van Houten, CEO Royal Philips 2014, 6

Something that is sustainable is maintained, continued in existence, or kept going over the long term. The basic concept is that we need to balance these three dimensions in our decision making. Even though we often discuss sustainability in the context of business operations, every entity, whether an individual, employee of a for-profit or nonprofit organization, or a government and its agencies, must address three basic questions for each activity or project in which we engage.

- • Is it economically or financially feasible?

- • How does it affect (positively and negatively) the air, water, land, and other elements of our planet?

- • How does it affect (positively and negatively) humans regarding their health, well-being, and quality of life?

Each dimension of sustainability has specific characteristics. Table 1.1 helps comprehend the importance of these dimensions, their strengths, limitations, and interdependencies.

Table 1.1 Characteristics of the dimensions of sustainability

|

Economic Dimension |

Environmental Dimension |

Social Dimension |

|

Represents transactions that have economic value and can be purchased or sold in the market place. |

Represents the surroundings in which we live including, but not limited to, the many ecosystem communities, their components, and relationships. |

Represents the activities that occur by living in groups or communities and the way group members treat each other. |

|

|

|

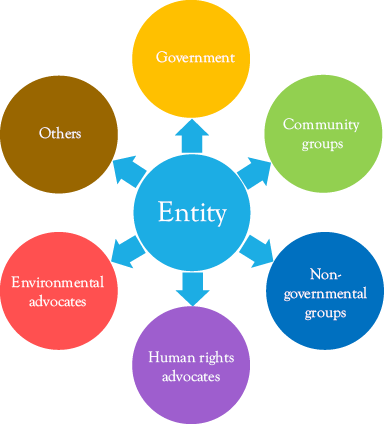

Stakeholders

To address the environmental and social dimensions, sustainable companies engage with their stakeholders to create wealth for all of those affected by their operations. Stakeholders are classified as both primary and secondary. Primary stakeholders engage in economic transactions with a company as shareholders, creditors, employees, suppliers, and customers and are often referred to as the company’s value chain. Secondary stakeholders are affected by a company’s activities and consist of regulators, governments, community groups, environmental and social institutions, and members of society, to name a few (Freeman 1984). Secondary stakeholders generally do not engage in economic transactions with the company, as primary stakeholders do, but are touched by a company’s activities either positively or negatively (Figures 1.2 and 1.3).

Figure 1.2 Primary stakeholders (value chain)

Source: Based on Freeman (1984)

Figure 1.3 Secondary stakeholders (indirect)

Source: Based on Freeman (1984)

Even though the change to a more sustainable society requires perseverance and innovation, the old way of doing business (only in the self-interest of the owners) will not work in a society that has limited resources to serve the needs and wants of a growing population. Therefore, when facing major global challenges (such as the elimination of poverty, a better standard of living for everyone, and the mitigation of climate change) companies that practice sustainable capitalism implement a strategy of sharing resources to remain competitive as a group or sector. The way forward is less about the survival of the fittest and more about joining forces so everyone survives and prospers. There is strength in numbers, and better outcomes can result when all are moving in the same direction.

Beinhocker and Hanauer discuss Redefining Capitalism in McKinsey Quarterly (2014). Considering the role of the stakeholders, they suggest that a better measure of prosperity or wealth, as well as the success of its economic system and its businesses, is the number of solutions to human problems society has produced. Consequently, rather than measuring the rate of growth by gross domestic product, a better indicator is “the rate at which new solutions to human problems become available” (p. 5). The conventional financial measures of business success such as profits, growth rates, and shareholder value are not indicators of solution generation for all stakeholders. Therefore, if an economic system and its businesses are generating more environmental and social problems than solutions for those problems, change is necessary.

Sustainability in Action: Benefit and Certified B Corps

Some corporations have concerns that solving society’s problems may conflict with increasing shareholder value, given that corporations’ legal responsibility is to their shareholders, not to society. Throughout this book we will study many examples of how a focus on all stakeholders actually increases shareholder value. However, to allay fears that sustainability activities may not increase shareholder value, the Benefit Corporation was created that legally allows the corporation to pursue sustainability initiatives and has legal obligations of accountability, transparency, and purpose.

Benefit Corporations may also wish to be certified, but there is no legal requirement to obtain a B Corp certification. B Corps receive their certification from the nonprofit organization, B Lab.

—Certified B Corporation n.d.

Sustainability in Evolution: Changing Expectations

To understand where we are regarding sustainability, it is best to understand how we got here. Therefore, we start with a brief history of the evolution of sustainability. There is a concept called legitimacy theory that underlies the sustainability concept and helps to understand the actions of organizations and how they must constantly change as society’s needs and desires change (Dowling and Pfeffer 1975). The theory in very simple terms is this. Hypothetically, society grants a company a social license to operate as long as it produces a good or service in a form that is acceptable to society. However, the types of products and the acceptable manner for producing those products change over the years. If a company does not change as society changes, it will no longer be allowed to operate.

Reflection: Which Products Lost Their Social Licenses?

Can you think of any products, services, or practices in the past that are no longer available due to a change in environmental or social standards?

Let’s look at a brief history of how the context of implicit social license has changed from 1945 to current times.

Economic Emphasis Only

During World War II (1940 to 1945), many resources were needed to support the war, leaving few resources for consumer goods. There was a shortage of consumer goods because most resources were used to produce war equipment and supplies. After the war people wanted to get on with their lives, set up their homes, and start families. When the war was over, everyone wanted a car, a refrigerator, a washer and dryer, a television set, and many other household goods that were not available during the war years.

Because of the enormous demand for products and very little capacity to produce these products (much of the world’s production capacity was destroyed), consumers were willing to accept any product that was available, defects and all. There was little concern about how it was produced or, within reason, how many defects it had. At that time, companies’ primary roles were to produce goods and services that consumers wanted. There was limited consideration of the role of business beyond its economic function. Organizations were deemed to be legitimate on the basis of the economic benefits they provided. If consumers did not perceive economic benefit, then the free market system based on supply and demand would deem the product unacceptable and production would be discontinued with little thought given to the environmental and social implications of the product’s production process. The sustainability model looked similar to Figure 1.4 with strong emphasis on the economic dimension and little attention paid to the environment and social dimensions.

Figure 1.4 Unbalanced and unsustainable

Growing Attention to the Environmental Dimension

Later in the 1960s and 1970s, our world population continued to grow and much of the world’s production capacity was rebuilt. Consumers could be selective about the types of products that they wanted to buy. Society expected goods and services that were economically beneficial without causing extreme harm to the environment. For example, Rachel Carson wrote Silent Spring in 1962 revealing the harm that the chemical DDT, widely used to rid agricultural crops of weeds, was causing to our bird population. As birds ate the plants that were sprayed with DDT, the shells on their eggs became very thin, causing birth rates to decline.

Growing Attention to the Social Dimension

The use of DDT also brought concern about health issues, placing emphasis on the social aspect of sustainability. Other social concerns also arose. In the 1970s factory workers fought hard with picket lines and strikes for safer working conditions and a share of the profits that they were instrumental in creating. Often corporations showed large profits, but employees’ wages remained stagnant. Companies pushed employees to work harder for increased productivity as global competition got stronger. Even today, we hear about poor working conditions, often in the textile industry, that are referred to as “sweat shops.”

Sustainability in Action: Quaker Oats’ Social Progress Plan

Although it took most companies some time to respond to a change in their business operations, Quaker Oats, a worldwide marketer of food and beverage products (now merged with PepsiCo), approved its first Social Progress Plan in 1964. The plan contained information on a great number of social topics, such as opportunities for youth and minorities, drug abuse, and health care, among others.

—Koch (1979)

Therefore, acceptable methods under which products were produced were changing. Society now wanted products that met higher standards: economically beneficial, socially acceptable, and environmentally responsible.

While Carson is often credited with initiating the environmental movement, many individuals promoted environmental awareness at this time. In response to a changing world context and changing definitions of what are legitimate products and services, in 1983 the United Nations convened the World Commission on Environment and Development (WCED). This Commission provided an opportunity for all nations to work together to address both human degradation and deteriorating environment conditions. The document that emerged from the Commission was published in 1987 and is referred to as the Brundtland Report or Our Common Future. It is named after the Commission’s Chair Gro Harlem Brundtland. The Commission recognized that finding solutions to our problems requires everyone’s efforts. Sustainable development was defined as “development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.”

- • “Needs” refers to the basic necessities of the world’s poor;

- • “Limitations” refers to the Earth’s resources as finite (Brundtland 1987).

In 1992 (five years later) the first international Earth Summit followed the WCED. Because it was held in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, it was called the Rio Earth Summit. The heads of state agreed to work together to address concerns regarding climate change, biological diversity, and loss of forests. The focus was primarily on environmental sustainability. Agenda 21 was the plan for implementing sustainable development, and a Commission was created to report on performance (United Nations 1992). Early attempts to achieve goals in one dimension sometimes were perceived to conflict with the ability to achieve goals in another dimension. Through experience organizations have learned to reduce the conflict and find joint solutions, but we are all learning how to resolve these conflicts in innovative ways. Throughout the chapters of this book, we will work together to clarify how the dimensions can be harmonized by using examples from companies that are finding a better way to do business.

Sustainability Models

After the Brundtland report, the United Nations has continued to lead the sustainability movement with accords, conventions, conferences, agreements, compacts, guidance, objectives, goals, and more. Stakeholders of all types have worked with the United Nations to support the movement, which we will study in the ensuring chapters. Illustrations can help us understand the evolution of these concepts.

Venn Diagram

Even though the diagram of the three overlapping circles of economic, social and environment (Figure 1.1) is likely the most common depiction of sustainability, as we learn more about sustainability, our thinking evolves as well.

Nested Circles

Because of concern that the scale of resource use might continue to grow to outpace the limits of our planet, the nested circle diagram joined the Venn diagram as a depiction of sustainability. This model shows that the economic dimension is a subset of society, and society is a subset of the natural environment. The nested circles diagram illustrates that companies and societies must not consume resources, especially nonrenewable, outside the limits of its carrying capacity (the number of people the planet can hold without harmful destruction) and without concern for the resources needed by future generations (Figure 1.5).

Figure 1.5 Sustainability: Nested circles

Sources: Based on Senge et al. (2008)

Millennium Development Goals

In 2000 the United Nations emphasized the social needs of people living in poverty, especially in developing countries. The eight Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) were introduced with a target date of 2015 for fulfilling the goals (see Figure 1.6).

Figure 1.6 Millennium development goals

Source: United Nations (2015)

Sustainable Development Goals

Even though considerable progress was made on the MDGs, world leaders felt that redirecting the goals into the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) would be more inclusive. Every organization and person should take responsibility for working toward the goals most relevant to them. This approach would increase participation through a world effort with every type of entity helping: for-profit; nonprofit; governments (cities, states/provinces, and federal); government agencies; universities; civil society groups; and individuals (Figure 1.7).

Figure 1.7 Sustainable development goals

Source: United Nations (2015)

With 193 countries of the UN General Assembly all working together the possibility would be much higher for accomplishing the 169 targets for the 17 goals. Even though sustainability is a continuous journey, the targeted date for reassessment of the SDGs is 2030. There is already a strong movement by companies to take on a role in achieving the SDGs.

Sustainability in Action: Unilever

The problems our society faces—such as climate change, inequality, plastic pollution and lack of sanitation—are urgent, large and complex. Change in our own business is not enough. We need transformational change to whole systems if we are to make a genuine difference on the issues that matter. That’s why we’re taking action on the UN Sustainable Development Goals through our transformational change agenda.

—Unilever 2019

Five Ps Model

With the expansion of the MDGs to the SDGs, the concept of the 3Ps expanded into the 5Ps, adding peace and partnerships to profits (sometimes broadened to prosperity), people, and planet (Figure 1.8) (United Nations SDG Guide 2015).

Figure 1.8 Sustainability: Five Ps

Source: Based on United Nations (2015)

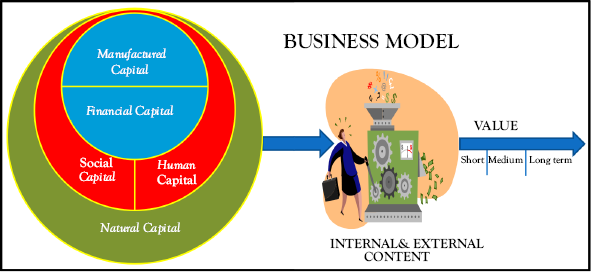

Five Capitals, Value Creation Model

Although not coming out of the United Nations initiatives, one more concept is worth mentioning here (discussed more thoroughly later). Porritt (2007) and his Forum for the Future has introduced the concept of maintenance of five capitals. The five capitals consist of financial, manufactured/built, natural, human, and social/relationship. The International Integrated Reporting Council (IIRC) added intellectual property as a sixth capital. Each capital (better defined as asset) is described briefly in Table 1.2.

Table 1.2 Value creation capitals model

|

Capital or Asset |

Relationship to Sustainability Model |

Description |

|

Financial |

Economic/profits |

Cash and other forms of near cash to be invested in the development of other capitals. |

|

Manufactured or Built |

Economic |

Material goods or assets used to manufacture or distribute product/services, such as equipment, plant facilities, computers, buildings, bridges, roads, and infrastructure. |

|

Natural |

Environment |

Resources coming from the planet including air, water, and land, renewable and nonrenewable that provide a flow of energy to produce goods and services. |

|

Human |

Social |

People’s knowledge, skills, expertise, motivation, beliefs, and spirit that are used in productive work whether paid or voluntary. |

|

Social or Relationship |

Social |

Institutions or relationships that support development, manufacture, distribution, and ownership of other types of capital, such as stakeholders (either primary or secondary). |

|

Intellectual (added by IIRC) |

Economic |

Brands, patents, copyright, reputation, and other forms of intangible assets flowing out of research and development, knowledge management, and innovation activities. |

Based on the work of Porritt (2007) and IIRC (2013).

The Capitals Model focuses on integrating sustainability more fully into the business model. The five capitals are similar to a statement of financial position or a balance sheet that lists an organization’s resources. Then, the company engages in a number of activities or business transactions using the five capital resources. These transactions appear on a statement of operations/income statement. However, the value creation capitals model more fully classifies the value (as outputs and outcomes, either negative and positive) into short, medium, and long term for all the capitals not just financial. If positive outputs/outcomes are greater than capitals consumed in the operating process, then value is created through maintaining or providing even greater stocks of the five capitals. Figure 1.9 illustrates the concepts. Notice that all the capitals are nested within the natural capital. Therefore, the development of these capitals should not exceed the limits of the carrying capacity of our planet.

Figure 1.9 Five capitals and value creation

Source: Based on the Forum for the Future (n.d.) and IIRC (2013)

Comparison of Sustainability Models

You might be thinking that you are overwhelmed by so many sustainability models and fail to see the relationships among the evolution of the six models this chapter addressed. However, think of the models as an evolution with refinements and extensions of the original model, not as completely different models. As we have gained a greater understanding of sustainability through experience and research over the years, our models have also included these greater insights. Table 1.3 summarizes the strengths and weaknesses of each of the models to comprehend how the weaknesses in one model lead to strengths in another model.

Table 1.3 Sustainability models: Strengths and weaknesses

|

Model |

Strengths |

Weaknesses |

|

Venn |

Easy to determine the meaning of the overlapping areas: profits as though the environment and people are important as well. |

Does not illustrate that society and the economy are subsystems of the environment and cannot expand beyond its carrying capacity. |

|

Nested Circles |

Illustrates a more realistic relationship of the economy and society as subsystems of the environment. |

Lacks detail on the various aspects or subsystems of the three dimensions. |

|

MDGs |

Provides more explicit goals for each of the subsystems. |

Tends to represent problems primarily in developing countries. |

|

5Ps |

Recognizes that sustainability is a joint effort and must be accomplished by nations (and their entities) working together peacefully and through partnerships. |

Difficult to define the overlap of each of the Ps. The illustration is more complex and difficult to understand. |

|

SDGs |

Provides more explicit goals for each of the subsystems, recognizing that both developed and developing nations and their entities must play a part to accomplish them. |

Gives the appearance that the goals can be accomplished separately but many are interdependent. |

|

Five/Six Capitals |

Parallels the business model and illustrates value creation as the primary objective of business and an economy. Emphasis on continuous improvement. |

Not well known or understood at this time. The interrelationships among the capitals are not always evident, especially to financial capital. |

Reflection: Your Personal Sustainability Model

Sustainability applies to every type of entity and every individual in our society. Although we might have the impression that our businesses create a greater impact than we do as individuals, if we accumulate the small impact of approximately 7 billion people of 2020, that creates a very large impact. Therefore, if each of us lessens our impact, together we can make a very large difference. Furthermore, we are our corporations. Many of us will work for corporations or buy products/services from large corporations. If we expect corporations to act responsibly then we ourselves must also act responsibly by choosing the types of products and services that we demand from our businesses. If you draw your three circles of sustainability to illustrate your lifestyle, what size would each of the circles be now and in the future? Are they of equal or unequal size? Why? Which SDGs do you see as most relevant to your lifestyle and how can you help to achieve these goals?

Anyone who thinks that they are too small to make a difference has never tried to fall asleep with a mosquito in the room.

—Christine Todd Whitman

Key Takeaways

- • We need to rethink capitalism to include sustainability and stakeholders. Many businesses are already incorporating these concepts into their business operations.

- • The basic model of sustainability considers the economic, environmental, and social dimensions. The model suggests that profits are important for an economy, but profits should not be the sole objective.

- • Capitalism as practiced by organizations should be designed to solve society’s problems not to create more problems.

- • Companies are allowed to operate only if they have an implicit social license.

- • Societal requirements for a social license evolve over time; business operations must evolve as well.

- • The Brundtland Report from the WCED stirred nations to come together to determine how to address international sustainability concerns.

- • As we learn more about sustainability, models depicting sustainability evolve as well. Some of the models include: Venn and Nested Circles diagrams, MDGs and SDGs, Three Ps or five Ps diagrams, and Values-Creating Capitals model.

Competition makes us faster. Collaboration makes us better.

—Author Unknown