Chapter 14

Ten Simple Rules for Swing Trading

IN THIS CHAPTER

![]() Taking prudent steps to become a successful swing trader

Taking prudent steps to become a successful swing trader

![]() Controlling your emotions (but still having fun)

Controlling your emotions (but still having fun)

Swing trading can and should be enjoyable. You can actually look forward to “working” each day! But swing trading is still a business, so you must stick to certain rules designed to keep you in the game. After all, if you have no capital, you can’t trade. So the most important rule is the rule of survival. Surviving means not only managing risk but also following your own plan and your own rules. If you’re not careful, swing trading can quickly go from being a business about making profits to being an outlet for your emotions.

The rules in this chapter aren’t novel or complex. Instead, they’re simple and straightforward. In fact, they’re downright boring. But they’ll keep you in the game and (ideally) help you make money. Stray from these rules at your own risk.

Trade Your Plan

A cliché that I hear over and over again is, “Plan your trade, then trade your plan.” I hate to regurgitate that here, but I can’t phrase it any better.

Your trading plan is your road map. It answers the following questions:

- What are your goals in trading?

- What is your time horizon?

- What will you trade?

- What tools will you use to trade (technical, fundamental, or a combination of the two)?

- How much capital will you allocate to your positions?

- What are your entry signals?

- When do you exit a position for a profit?

- When do you exit a position for a loss?

© John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

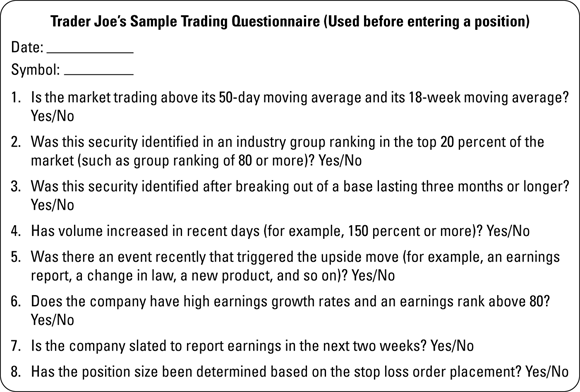

FIGURE 14-1: A trading questionnaire is a useful tool that helps you stick to your trading plan.

Your trading questionnaire may be more or less complex than this sample. Either way, having such a questionnaire forces you to think through the important issues you may overlook when you’re making decisions on the fly. Stick to a trading questionnaire, as silly as you may think it sounds, and you’ll find the success of your trades increasing. The more errors you avoid, the more likely your trades will turn out profitable.

Follow the Lead of the Overall Market and Industry Groups

If you’re trading stocks, you want the wind at your back, meaning your trades should be in the direction of the overall market. If the market is in a strong bull market, then you should be close to fully invested. And if the market is in bear mode, you should be holding cash (or seeking bull markets in international markets). Markets may also be stuck in trading ranges, in which case you should opportunistically buy strong setups while avoiding too much risk given the lack of market direction.

But trading with the overall market is only part of the story. The skilled swing trader recognizes that industry groups make a difference in a security’s returns. When an industry group is in the top of the pack (as identified in High Growth Stock Investor software or eTables by Investor’s Business Daily), the stocks in that group are likely to follow suit. Conversely, when an industry group is in the bottom of the pack, the stocks in that group are likely to follow suit. When tech stocks fell out of favor in late 2018, most all tech companies were affected irrespective of their fundamentals (see the examples in Figure 14-2).

© John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

FIGURE 14-2: Most securities in the technology industry fell in unison in late 2018 given high valuations and fears of an economic recession.

Don’t Let Emotions Control Your Trading

Humans are affected by emotions. But allowing your emotions to rule your trading decisions can be disastrous.

In fact, emotions can be your biggest enemy. In a sense, you are your own worst enemy. Traders who lose billions of dollars at major banks often start out losing a small amount and then try to break even or prove themselves right. Their ultimate failing lies not in their analysis or their market knowledge but in their inability to control their emotions.

Another factor in controlling your emotions is keeping tabs on your trades. Don’t brag to others about your profits. Don’t tell others about any trades you’re in at the moment. Do so and you become married to your positions. If you tell your best friends that you hold shares in Company A and you believe the share price is going to skyrocket, you’ll be less likely to exit if the trade turns down. “Oh no!” you may say to yourself. “Everyone knows I hold Company A. I can’t bail now. I’ve got to hold to prove I was right.”

Controlling your emotions isn’t something that just happens one day and you never have to worry about it again. Rather, it’s an ongoing battle. The two strongest emotions you’re going to face are greed and fear. When markets are roaring in one direction and you’re riding that wave, you’ll want to hold positions longer than you need to as you amass more profits. And when markets roar in the opposite direction and your profits evaporate, you’ll want to take more risks to make up for those losses.

You can’t battle these emotions in any scientific way (that I know of, at least). I’ve always imagined that a Spock-like character who’s always rational and never lets emotions interfere with his trading would make a wonderful trader. Unfortunately, Star Trek is a fictional story, and Vulcans don’t exist. So as a trader, you need to review your trades carefully and practice being calm as much as possible. Be disciplined enough to force yourself to stop trading if you detect your emotions are driving your trading.

Diversify, but Not Too Much

As a swing trader, you must hold a diversified portfolio of positions. You should have at least ten different positions, and they should be in different sectors. And if you can, incorporate other asset classes in your swing trading. For example, include technology stocks, developed market equities, emerging market equities, and ETFS Physical Gold (assuming these securities meet the fundamental and technical criteria of your strategy).

But too much of a good thing can harm you. It’s possible to diversify too much — holding say 30 or more positions. A swing trader needs concentration to make large profits. The more positions you hold, the closer the returns of the portfolio will be to the market.

Set Your Risk Level

Setting your risk level goes hand in hand with setting a stop loss level, which I discuss in “Use Stop-Loss Orders” later in this chapter. Entering a stop loss level is an order entry step, but setting a risk level is an analytical part of the process. Your stop-loss order will often be at the risk level you identify in this step.

Your risk level represents the price that, if reached, forces you to acknowledge that your original thesis for trading the security is wrong. You can set your risk level based on some automatic percent level from your entry order, but I don’t recommend this because it forces a reality on the market where one may not exist. For example, say you automatically exit a position when a security declines by 5 percent. But why should that security stay within this 5 percent range? What if the security’s daily volatility is 3 percent? It may hit your risk level in a day or two just based on normal volatility.

Your stop loss level should be set at your risk level. But formulating your risk level depends on what your trading plan calls for. If you don’t want to use some obvious support level, then use a moving average, but be prepared to constantly adjust your stop loss level because the moving average is constantly changing. The wider your risk level is (that is, the farther your risk level is from your entry price), the smaller your position size should be. This rule of thumb ensures you aren’t risking more than 1 to 2 percent of your total capital because you may be entering a security that’s extended.

Swing traders who focus on trading ranges have an easier job of identifying their risk levels. They’re looking for a continuation of an existing trading range. Hence, a breakout above or below a resistance or support level would signal the end of the trading range. That resistance or support level is the most obvious risk level for the swing trader.

Set a Profit Target or Technical Exit

I stress risk management a lot in this book. The reason is simple: You can’t last long without it. But when it comes to profits, you must set your profit target or technical exit.

My preference in taking profits is to rely on a signal from a technical indicator rather than a pre-existing support or resistance level. Some securities trend longer and farther than anticipated, and they can be very profitable. Hence, I prefer to exit after a security breaks below an indicator, such as a moving average, or on a sell signal from a trending indicator.

Chapter 5 covers how you can exit positions based on moving averages.

Use Limit Orders

When entering or exiting a trade, you should use a limit order rather than a market order. A limit order ensures that your execution occurs at the price you specify, whereas a market order can be filled at any price. Rarely will you encounter such urgency to get into or out of a trade that you’ll need to enter a market order. Moreover, you’re unlikely to buy at the bottom of the day or sell at the top of the day. So be patient and you may get a better price than you originally thought.

Another reason to use limit orders is to help you avoid the cost of market impact. The larger your order size is relative to the average volume that trades in the security on a typical day, the more likely your buy or sell order will move a security’s price higher or lower. A market order in a thinly traded stock may leave you with an execution that’s 2 to 5 percent above/below the price the security was when you entered the order.

You can place a limit order at a price level near where shares have traded. The intention is to control the average cost per share. Place a limit order slightly below recent trades (when you’re buying) or slightly above recent trades (when you’re exiting).

Use Stop-Loss Orders

You may think that stop-loss orders are nothing more than training wheels. “I’m an adult. I don’t need these pesky stop-loss orders. I can exit when I see weakness.” Unfortunately, that kind of thinking may get you killed (financially speaking, of course). Financial markets aren’t playgrounds or appropriate places to find out who you are. Leave that to your local sports club.

Stop-loss orders are necessary for several reasons — even if you watch the market 24 hours a day, 7 days a week:

- They help you deal with fast-moving markets. If you swing trade ten different positions, it’s quite possible that many of them may start acting up on the same day. And they can move fast and furious if negative news is in the air. Because of the speed at which markets move, you need a stop loss to save you if you’re unable to act.

- They limit your downside. Without a stop-loss order, your downside may be all of your capital. Stop-loss orders act as protection, because they place some upper limit on the losses you may suffer. Of course, a security could gap through your stop-loss order, but your loss would be realized then regardless of whether a stop loss order existed.

- They help take your emotions out of the game. When you place mental stop-loss orders, you may start to arbitrarily move your imaginary stop loss as the markets move against you. So, you plan to exit at $49.50, but when the security trades through that price down to $49, you tell yourself that $47.50 is a more reasonable exit point given recent market action. You justify your change and you hold on. And your losses mount.

- They give you time to take your eye off the ball. If you travel or are unable to watch the markets on a day when you’re sick, stop-loss orders ensure that your portfolio value is preserved. If you didn’t have stop-loss orders, you’d probably fear ever being out of touch with your computer and the markets. One or two lousy positions can quickly change a top-performing account into a poor performer.

For these reasons, stop-loss orders are essential. You’ll sleep better at night if you know that someone is watching your positions, ready to take action if they start acting up.

Keep a Trading Journal

Trading journals organize your thoughts and the reasons behind your decisions. They should be updated after every trade you execute. If you delay entering a trade into your journal, the trades may eventually pile up and overwhelm you, and you may decide not to update the journal anymore.

Have Fun

This last rule may strike you as a bit off kilter. After all, earlier in this chapter I recommended managing your emotions and the joy or pain that comes from gains or losses.

Yes, yes — I did say that. But this final rule goes to the heart of whether you can be a full-time swing trader. You have to like the business. You have to enjoy spending hours on the computer looking for investment candidates. You have to find pleasure in reading books about swing trading (especially this one, of course).

If you have to force yourself to research positions, then swing trading may not be for you. If logging onto your brokerage account is a painful exercise you prefer not to do because you feel ashamed, swing trading may not be for you. Even when you’re down, you have to be optimistic that your profits will come soon. And that optimism helps make those profits a reality.

So enjoy swing trading and all it entails. You’ll find it can be a rewarding experience — financially and otherwise.

Trading plans must be carefully thought through and then written down. I prefer to keep a copy of my trading plan nearby, or a digital version of the plan accessible on my laptop. One tool I use to make sure I follow my trading plan is a questionnaire I developed that I always complete before I enter a position. I provide a sample questionnaire in

Trading plans must be carefully thought through and then written down. I prefer to keep a copy of my trading plan nearby, or a digital version of the plan accessible on my laptop. One tool I use to make sure I follow my trading plan is a questionnaire I developed that I always complete before I enter a position. I provide a sample questionnaire in  The industry group in which you trade is more important to your success or failure than which company you pick in that industry group. So, as a swing trader, concentrate purchases on industry groups that are in the top 20 percent of the market. You can also identify promising candidates in industry groups gaining strength (either by examining the industry group chart or by examining groups with increasing group strength).

The industry group in which you trade is more important to your success or failure than which company you pick in that industry group. So, as a swing trader, concentrate purchases on industry groups that are in the top 20 percent of the market. You can also identify promising candidates in industry groups gaining strength (either by examining the industry group chart or by examining groups with increasing group strength).