CHAPTER

1

Here, there, and everywhere … anytime at all

The application of digital technology to the production, distribution, and consumption of media has ushered in the ability to consume content anywhere, anytime, on any device over more delivery channels than any broadcaster or consumer knows what to do with. In order to compete in the diversified twenty-first century media universe, television broadcasters must produce and repurpose content for all possible delivery channels and reception devices.

As if television broadcasters didn't have enough of a challenge converting to digital production and distribution, now they are faced with the reality that this new media universe requires content to be available to on any platform. By 2008, television production companies, national networks, local broadcasters, and cable TV ser-vices realized they had no choice but to distribute content over the Web and to cell phones and other mobile reception devices. Yet ways to derive revenue, much less profits, from “new media” have been elusive.

Just take a quick inventory of all the “new media” channels that have become available in the last few years: cell phones, BlackBerries, PlayStations, media center PCs, personal digital assistants (PDAs), digital cinema, digital signage, the World Wide Web, taxi TV, elevator TV, gas station TV, and good ol’ print!!! And just to add to the distribution options: Wi-Fi, WiMAX, mobile TV, iPods, iPhones, and don't forget the Internet!

Television distribution also continues to diversify. For more than a decade, over the air, cable, and satellite were the only TV delivery options for consumers. But now, telcos and new media are getting into the act. The acronyms are plentiful—HDTV, RFoG, IPTV, FiOS PC, SDV, VoIP, VoD—even if few consumers know what they all mean.

For broadcast engineers and media technologists adapting to the new technologies and expertise required to design, install, commission, and maintain systems that support producing and distributing content over multiple distribution channels, a new level of complexity has been added to existing broadcast infrastructures. New fields of technology, the integration of IT, and software development have created an infrastructure that is a system of systems. Each area of expertise requires a career's worth of professional competence.

Lost in the need to master esoteric technical details is the big picture, the 5 0,000-foot view of how all the pieces—the equipment, the production workflow, and the techniques that support the repurposing of content—fit together. This book aims to put together all the pieces of this system-of-systems engineering puzzle.

ONE FOR ALL

Repurposing broadcast TV programming is really nothing new. Retransmission of terrestrial network content over cable and satellite systems has been happening for decades.

Many a television broadcast company owns radio stations as well. And news-paper and magazine publishers have owned TV and radio stations for years. Every media company has consumer-oriented Internet sites; these microsites are often tied to a specific show, magazine, or other niche audience. But things are different now. Rather than having individual business units and separate production departments for each distribution channel, new computer-based systems and a profit-conscious business environment have enabled and necessitated integration of systems and given rise to a mantra of “produce once, distribute everywhere.”

Adding to the increasing mass of content is user-generated media. Thanks to the abundance of personal computing power and the proliferation of easy-to-use authoring tools, content consumers have become content producers. Cell phones feature digital cameras and the ability to capture short video clips. Inexpensive production applications format and upload personal productions to social Web sites with a click, and voila, everyone is instantly a publisher with the entire world as the potential audience.

Such is life in the digital media universe.

Digital = Power

Digitized audio and video can be reformatted, converted, and repurposed for any possible delivery channel at a quality level beyond the capability of analog technology. Couple this capability with the rapid deployment and consumer uptake of each new delivery channel, and 2009 marks not only the end of analog over-the-air television in the United States, but also the birth of a new multiplatform global broadcasting paradigm.

Content is now targeted for global distribution. For the Internet, the multiplatform capability already exists. For digital television (DTV) it involves reformatting content, and the 25/50 Hz vs. 29.97/59.94 Hz video frame rate issue has been augmented by compression codec transcoding requirements.

There are two technology variables that enter into the digital universe transformation equation. The first is the transmission of digital audio and video content over a limited data capacity delivery channel. The other is the development of digital production processes and workflows. This book will delve into both and demonstrate that there are many solutions to this system of equations.

Digital television: the ultimate digital challenge

The doorway to this new universe began with the ability to digitize television, or more specifically, video content. Conventional wisdom in the late 1980s said that the ability to digitize a high-resolution TV image so that it could be transmitted over a standard 6, 7, or 8 MHz channel (depending on the national TV system) was probably a decade in the future.

For many decades television was the only “show” that could be enjoyed in the home. Over-the-air distribution, typically referred to as terrestrial television, and the advertiser-supported business model had remained largely unchanged since the first broadcasts. There were no VCRs and few reruns; networks could count on a by-appointment-viewing audience. Television was magic!

Terrestrial television's success was its own undoing, as those in areas with poor reception wanted better TV audio and video quality. By the 1970s, a threat loomed on the horizon, just out of the range of terrestrial transmission.

What began as community antenna systems (CATV) in the 1980s to solve reception problems now began to offer nationally distributed programming. Cable net-works (more correctly called “services”) distributed content across the country via satellite to local cable companies for distribution. Little by little, cable TV distribution and penetration steadily eroded terrestrial audience numbers.

Direct-to-consumer satellite broadcast services were virtually nonexistent in the early 1980s, with the exception of technology pioneers who installed 6' C-band dishes in their yards. But by the mid-1990s, new digital technology spurred a resurgence of the delivery channel. By then, terrestrial networks and local broadcasters had faded to a third in the percentage of households for each distribution channel.

But terrestrial broadcasters as early as the mid-1980s realized the potential cable TV had for reducing their audiences. In response the U.S. TV industry and government supported an analog high-definition television (HDTV) proposal for a system based on the work of NHK, a Japanese corporation. One motivation was to slow terrestrial viewer erosion by offering something that would be technologically unappealing to cable operators but highly appealing to audiences. Interested in channel quantity rather than picture quality, cable operators liked the fact that DTV allowed them to offer “500 channels” and maximize use of their installed delivery channel capacity, rather than “waste” bandwidth on HDTV.

Another threat in the United States was the growth of cellular services. Although the use of cell phones had not grown to mass acceptance, Motorola and others lobbied for access to radio spectrum frequencies that were not in use by TV broadcasters. TV was threatened and didn't take well to the idea of losing its “sacred” spectrum. HDTV became a rallying cry to fend off the attack.

Just as this threat was turned back another appeared, but few could foresee just how big a threat this technology would really be. By 1995 the “consumerization” of the previously academic and commercial Internet had just taken off with the introduction of Netscape and Windows 95. Conventional wisdom proclaimed that real-time audio and—surely you jest—video could never be delivered over the Internet to personal computers (PCs).

Still, there were a few enlightened technologists in the TV engineering biz. So when the Grand Alliance (a consortium of corporations and institutions) developed a digital HDTV prototype, the Federal Communication Commission (FCC) mandated the ability to packetize the bit stream for transmission over a computer network: The emerging Information Highway had to include DTV.

In the end, the FCC adopted this prototype DTV technology, documented by the Advanced Television Systems Committee (ATSC) standard, in 1996. Few envisioned then how the transition to DTV broadcasting would become the technological catalyst that would transform the entire content distribution and consumer electronics industry.

NEW UNIVERSE, NEW AGE, NEW MEDIA

At the turn of the millennium, consumer content delivery channel categories—TV, Internet, and cellular—were independent of each other. Distribution channel capacity and content data volume prohibited cross-platform exchange. There was no way to get broadcast TV over the Internet; the technology simply couldn't do it.

In the new millennium, low-quality audio and video streamed from servers began to proliferate in cyberspace. There was just enough bandwidth to download short video clips to a PC. It was possible to fit 2 Mbps video over a 56 kbps modem. One minute of video would (ideally) take 2,143 seconds—close to 36 minutes!

At the same time, PBS and others began to use the gift of a second channel for HDTV as a means to distribute more than the primary digital TV program. They started by adding a multicast channel to a terrestrial broadcast, most often a weather forecast.

Cell phones were still in their infancy and used for making calls or text messaging. Advanced audio and video and even access to the Internet were still in R&D.

Fast-forward to 2008. The repurposing of TV programming is rapidly expanding to Web sites, cell phones, and soon to mobile DTV. Digital technology also enables interactive entertainment, targeted advertising, and personalization of the media experience on all platforms. In the end, the distinction between devices will become increasingly blurred. Television is not just television anymore.

A numbers game

All distribution platforms are dependent on audience numbers for generating revenue streams. This makes business life difficult in the contemporary, multiplatform universe where audiences are fragmented and in control of when and where they consume content.

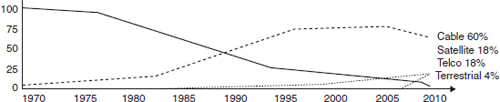

FIGURE 1.1

Percentage of U.S. TV households for terrestrial, cable, satellite, and telco delivery channels since 1970

The migration of terrestrial TV audiences to other delivery channels can serve as a lesson. Unchallenged for over the first 30 years of their existence, terrestrial broad-casters have seen a complete realignment of TV audience distribution over distribution channels that have emerged since about 1980.

Consider present-day TV audience segmentation. Terrestrial television viewers make up less than 15% of the total TV audience. Cable distribution is dominant at over 60% but experiencing churn to direct broadcast satellite (DBS). Telcos are in the TV game now, with fiber optic service (FiOS) and Internet protocol television (IPTV) services, and are gaining subscribers at a slow but steady rate. Figure 1.1 tracks the growth of TV audiences in the United States since 1970 by distribution channel.

In other nations the delivery channel mix varies, but the important point is that TV content is available over a variety of delivery channels. The only similarity among most countries is the progressive disappearance of radio frequency (RF)-based terrestrial television broadcasting.

This is bad enough for TV networks and local broadcasters, but matters have got-ten worse. While networks were busy battling with cable and satellite challenges, cyberspace delivery channel capacity grew exponentially. And one day the fledgling, text-based Internet came of content delivery age. By 2007, the rich media Web had become a contender for television audiences.

There are many that will tell you that eventually all TV will come over the Internet. This may not come to pass. But one way or another, consumers will get their content at any time, in any place, on any device.

Technology timing is everything

New media distribution channels, now with adequate and growing capacity to deliver broadcast-quality content along with interactive and personalized features that terrestrial broadcasters could only dream about, have completely transformed the entire media business. As a result, TV broadcasters have embraced multiplatform distribution. As “pipes” (bandwidth of distribution channels, measured in bits per second) to the home get bigger, broadcasting quality content over the Internet is becoming practical if not initially profitable. Delivery of TV content to cell phones, PDAs, and other mobile devices is accelerating.

Around 2005 all necessary technologies coalesced with emerging media consumer trends to reach critical mass. Just as Chairman of RCA and founder of NBC David Sarnoff had to realize that TV is not just radio with pictures, so too did broad-casters have had to realize that the Web, cell phones, and other new media are the future; TV penetration has reached the point of nearly 100% saturation in modern nations and so has little room to grow on its own.

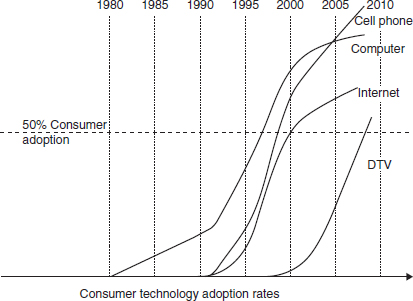

Many factors have contributed to this confluence of delivery channels and the need for integrating platform-specific production processes. Figure 1.2 depicts the relationship among channel delivery technology and consumer adoption. What is important is not so much the actual numbers, but the fact that by 2008, delivery of high-quality TV content is possible to all consumer reception devices.

The resultant multiplatform digital media consumer experience has disrupted the TV and media industry. Internet reruns of yesterday's broadcasts, extra program-related content on microsites, video clips, and cell phone weather updates are available at any time and often for free. Niche services on cable systems enable a viewer to browse for sale listings for homes and cars. You can check movie times and order tickets, and pre-view an upcoming TV season. The TV experience is becoming more like the Internet.

Media industry business models are changing. The Internet has opened the door to distribution of consumer-generated content to millions with the click of a mouse. Originally nothing more than someone's personal opinion expressed in text and posted to a newsgroup, consumer-generated content on the Internet progressed to personal home pages and sophisticated social networks. The Web has enabled any-one to distribute content on a global scale. Pick the right key words or hit on an interesting theme, and in the course of hours millions will visit your site, or at least your video on YouTube.You're instantly an international star!

FIGURE 1.2

Technology introduction and consumer uptake of “new media”

The pros get into the act

Up until recently content was produced and specifically tailored for the aesthetics and technical constraints of a particular delivery channel. Radio broadcasts may have spawned TV shows, but radio content stayed on the radio. Print was a world unto itself; maybe a movie or TV screen shot or publicity photo would make it to publication. Analog technology did not support using the same content easily on different platforms. That's all changed.

In a multiplatform universe, content production personnel have a lot more to be concerned about than they did in the channel-specific past. Because content will be repurposed for multiplatforms, talent, writers, graphic artists, and everyone involved in the creative process now must produce multiple versions tailored for delivery over a multiplicity of distribution channels.

But don't get carried away by the romance of new media too quickly. TV still rules the roost and attracts the largest audience numbers. Still, audience preferences are changing. In April 2008, 120 million Internet viewers downloaded a cumulative total of 7 billion videos! These numbers are just too large to ignore: Video quality issues aside, people watch video over the Internet. They find it entertaining.

What began as a wild chase by media companies for new revenue models has settled into a deliberate thrust into new media for both traditional and emergent content providers. The wise broadcaster is avoiding being backed into a corner and locked into fading, outdated business models by experimenting with new content formats and new distribution channels. This requires a new take on the media business; this book will show you how the old and new components all fit together.

CONSUMER ELECTRONICS PROLIFERATION

Numerous reports have been dedicated to announcing the death of traditional media such as TV and radio, heralding the Internet as the future of all media distribution. Technology journalism, being what it is, constantly emphasizes the latest and the greatest. But a careful examination of consumer device proliferation and audience consumption patterns paints a different picture.

Mass broadcasting

The oldest means of disseminating content is the “one-size-fits-all” methodology. Content is produced in a single format or fixed medium, and distribution is to the world at large. This was the method followed by TV and radio since their inception. Technology limitations restricted any type of personalization.

I'll say it again: TV is the heavy hitter, period! No other content distribution channel commands audience numbers anywhere near those gathered by an individual TV broadcast. Consider the ratings for annual events like the World Cup, Super Bowl, and Academy Awards. These events are massive global communal experiences and become shared memories, creating a common bond among all who watched.

Audiences are measured by the hundreds of millions of global viewers. In an advertising-supported business, nothing else offers even remotely equivalent reach and commands a similar price per second of commercial time.

DTV, in particular HDTV, has given new life to global consumer electronics. In the United States, the long-awaited analog shutdown has occurred. Global shutdown of analog TV is scheduled over the next five years. HDTV adoption has been steady in the United States and is poised to explode globally. DTV sales have surpassed analog sales.

From November 1998 when the first HDTVs went on sale to 2004, 13.5 million households made the transition to HDTV. By 2010 this number is expected to reach more than 82 million—about 80% of all homes in America.

Program vs. Product

ABC News Chairman Roone Arledge was a visionary. The legendary memo he wrote over a can of beer in Armonk, N.Y. brought “show business to sports.” The production and programming concepts and production techniques expressed in those few pages are the foundation of modern television communications. Yet, as he detailed in his posthumously published autobiography, when he heard programming referred to as “product”, he knew the business had changed and it was time for him to leave.

TV's founding fathers are nearly all gone. Management has moved on to a second and third generation, people who cannot remember when there was no TV to occupy their time. What was once the viewing audience has become a sea of consumers, to be manipulated and bartered for advertising dollars. Their habits are measured in terms of media consumption.

It is important that content producers not lose sight of their position in the grand scheme of existence as new distribution channels emerge. As Edward R. Murrow said—to educate, inform, and enlighten.

Other forms of mass content do exist. It would be hard to watch a TV program while driving. First radios and then other audio systems have eased the stress of driving for millions. Later, audiocassettes and CDs enabled personalization of the listening experience. Today, drivers “rip” their own fully personalized CDs or load MP3 audio into their car's music server.

There is an ongoing love–hate relationship between the movie industry and tele-vision. TV severely impacted movie attendance in the 1950s. In response, the film industry sought technology that would give it an edge over TV. Widescreen theaters and later 5.1 surround sound succeeded to some extent in lifting audience numbers.

Another way erosion of move attendance has been offset is through the sale and rental of video home system (VHS) cassettes and now DVDs. For many, stopping at the rental store became a Friday night ritual. Modern technology is eliminating the need for physical media because movies are available on televisions via video on demand (VoD) and on PCs via download.

Personal entertainment

It's a cliché, but true nonetheless, that change is the only constant; for technology, doubly so. No one can live in a first-world country today without access to a computer and at least a basic ability to use it. Cell phone uptake is beyond 100%.

Personal computing

Since the introduction of the personal computer in the early 1980s, business as well as social and educational endeavors have become dependent on the PC. Almost everyone uses word processing and spreadsheet applications daily at work. At home, the PC pays the bills and stores the family photo album.

The growth of the PC has been exponential. Since the rollout of Windows-based operating systems, increasingly more entertainment applications have been available on PCs.

Initially, PC media capabilities were limited. Computer games, an early “killer-app, ” featured graphics that were little more than stick figures and backdrops created with a 16-color palette. Clock speeds of 12 MHz and 640 kilobytes of RAM were all a top of the line system could offer. That's nowhere near powerful enough for media applications.

Yet sales of PCs in the United States grew rapidly. It took 15 years for yearly sales to go from virtually zero to 50,000 units by 1995, but in only five more years they jumped to 125,000 and hit 200,000 per year by 2005.

Recent growth has been even faster outside of the United States. Estimates place the number of PCs in the world at a billion or more. It truly is an interconnected world.

An interconnected world

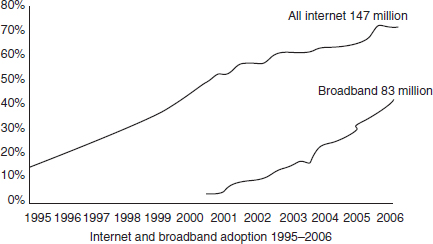

The Internet exploded on the consumer landscape in 1995, and user numbers grew exponentially for the next decade (see Figure 1.3). Even the “dot.com” bust in 2001 did not significantly impact consumer uptake.

The Web is becoming acceptable as a viable outlet for television programming, but video quality remains the pivotal issue. There are innate technical issues that categorically make it nearly impossible for broadcast quality, especially HDTV, to be delivered over the Internet. But viewers are willing to accept low levels of video quality online that they would never tolerate on their televisions.

FIGURE 1.3

U.S. Internet and broadband adoption 1995–2006

So how bad is so bad that a viewer will not watch? It's all relative. If the clip I'm watching is just a user-generated video of someone's frog jumping through hoops, it's no great loss. If it's the U.S. Open golf tournament playoff, a dedicated fan will tolerate any level of picture quality, no matter how bad it is.

Yes, content is king, and many would rather watch a less-than-optimum presentation of something they are interested in or find amusing than channel surf the TV only to find nothing they really want to watch.

The Digital Divide and Freedom of Expression and Information

The digital divide is real. Those that stand to benefit most often can't afford to buy the liberating technology. What good is an Internet-delivered discount if you can't afford a PC or access to the Web?

The freedom of expression and access to information in cyberspace that so many enjoy and take for granted is not always available to others around the world. Democracies depend on citizens who are aware of issues and policies, who know what is going on inside the country and around the globe.

Those in power manipulate the media; the media seek the truth but can't help to put a spin on it. Meanwhile, the rich get richer and the poor…well the poor, they just exist and struggle to survive.

One would hope that our new multimedia universe will be used to better the world we live in.

Gaming

The development of PC media capabilities was spurred on by the consumer adoption and business success of PC video games. Competition among application developers was fierce. Improved realism was a marketplace advantage. PC manufacturers saw video games as an opportunity to sell more PCs. Increased effort was expended on developing dedicated graphic processing chips. These integrated circuit cards were incorporated into the system architecture and enabled 3D graphics and near-photorealistic rendering.

With the inclusion of high-end graphics engines, the ability to deliver CD audio and DVD video was attainable. Ensuing generations of PCs included CD and then DVD players. The PC began to supplant consumer electronics.

Free to roam

Reaching consumers with content when they were not at home has always presented problems to media distribution efforts. From a business perspective, employee productivity suffered when employees were away from the office. This was a great incentive to develop mobile phones.

Today, mobility has extended beyond cell phones to mobile computing and DTV.

Cell phones

Untethered verbal communication was a natural extension of landline-based tele-phony. The meteoric pace of consumer cell phone adoption attests to the need to communicate. Universal cell phone availability has changed the communication hab-its of the entire world.

As impressive as the U.S. cell phone uptake numbers may be, they are dwarfed by global adoption. This reality adds more incentive to plan to repurpose content any-place, anywhere, at any time on any device.

From their first consumer introduction, designers of cell phones have striven for higher quality and the addition of more features. 4G (fourth-generation) phones loom on the event horizon, bringing more features and a higher quality video and audio experience.

Portable media-capable devices

Since the dawn of broadcasting people have desired to consume content where-ever they are. Even in the pre-TV days, large, vacuum-tube, battery-powered portable radios made the trip to the beach. In time, portable TVs and cassette music players, as well as radio, benefited from the technological advances that enabled miniaturization of electronic components.

Media is all about creating an event. The same holds true for consumer electronics. When the Sony Walkman debuted in Japan in 1979, the media consumption paradigm was forever altered. Previously, portable audio cassette players were about 12″ × 5″ × 4″ high—portable, but bulky. The Walkman could fit in a pocket. Cassette recordings could now be listened to while walking, jogging, or anywhere.

With the limited capabilities of cell phones, it was only matter of time until high-end, handheld mobile computing devices were introduced. These PDAs were mini computers that had limited connectivity to the Internet and could be synchronized with office documents and e-mail.

Given that the advance of technology to support features desired by consumers is inevitable, these early PDAs have grown to the point of including media capabilities. And along the way, cell phones have become “smart phones” and are in essence PDAs. Regardless of what they are called, they can now receive some form of DTV.

Laptops

Use of a laptop computer for media enjoyment has become commonplace. CDs and DVDs can be enjoyed anywhere. Plug in an ATSC DTV tuner to a universal serial bus (USB) port and voila—you can enjoy your favorite terrestrial programs anywhere in reach of a signal. No ghosts or echoes; just perfect digital images and sound. And as wireless networks increase in data delivery capacity, people are increasingly able to view Internet-delivered audio and video from their laptops while away from home.

ACROSS THE MULTIPLATFORM UNIVERSE

For a long while, consumers were perfectly happy to just talk on their cell phones, play games and surf the Web on their PCs, and watch a sitcom on their TV. The idea of doing any task on any consumer device was unthinkable.

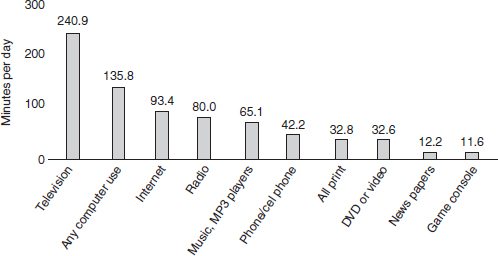

Today, daily use of multiplatforms for media consumption and entertainment is spread across a wide variety of platforms. Old-school platforms such as TV, radio, and newspapers have given way to new media channels. Figure 1.4 is a generic breakdown of the number of minutes on each platform spent by a consumer in a single day.

FIGURE 1.4

Media use on an average day by consumers of all ages (Ball State, PEW May 2006)

What is important about this graph is not so much the actual minutes per day spent on a particular platform, but the general trend toward platform diversity.

The impact on content producers, media conglomerates, and business Web sites of the consumers’ ability and desire to enjoy media on any platform is transforming content distribution philosophy. A continually increasing number of distribution channels vie for consumer minutes per day.

Personal vs. Professional

Thanks to the Universal v. Sony Supreme Court decision, anyone born in the U.S. after 1984 has never been restricted from recording TV content on a VCR. And as the ability to copy audio became ubiquitous, few people gave a thought to the fact that these were copyrighted works, and copies were distributed freely over an Internet-connected world. The distinction between personal and professional creative rights was blurred to the point of imperceptibility.

Content owners have cried bloody murder about illegal copying and consumer copyright infringement. However, they are not so clean as to be justified in throwing stones. In all their concern over lost revenue from illegal copying, downloading, and sharing of media, they have dragged their heels in paying royalties to the writers, artists, and other creative personnel that produce the content they are exploiting.

Audience segmentation

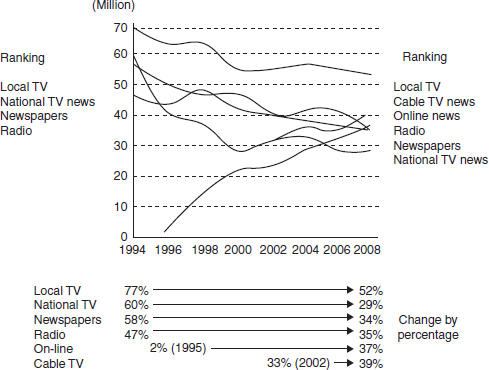

A look at changes in how people get their news exemplifies the general trend in audience segmentation. Newspapers are a mainstay of the information dissemination business, and their status as the ultimate authoritative source went unchallenged for decades. Eventually, evening TV news broadcasts began to alter the news audience consumption platform demographics. Today the Internet has cut deeply into the newspaper industry, disrupting the newspaper business model, as classified ad space is virtually nonexistent. Figure 1.5 traces the trends in channels that consumers turn to for their daily news.

Since the rise of consumer online activity, newspaper readers have diminished from about 58% of the U.S. population to just about 34% in 2008. Internet news access has grown from 0% to 36% and recently surpassed newspapers. Radio has declined to about the same level as the Internet and newspapers. Not surprisingly, the cable news audience has increased to 40% and is in the number 2 position behind local TV.

It's really a no-brainer: News companies must deliver news over the distribution channels consumers prefer. So Web sites and cable outlets are a necessity if a news company wants to stay in the game. Yes, the times they are a (still) changing.

Similar, although not as drastic, audience segmentation is occurring to TV, radio, and magazine consumption audiences. The Internet is mostly to blame, by offering access to niche radio programming, broadcast TV programs, and the entire library of amateur content.

FIGURE 1.5

Change in consumption of news over time on different platforms in the United States (Ball State)

Distribution diversity and the emergence of new media

It was the policy of the Clinton administration to deregulate the telecommunications industry. And as the industry was deregulated, and long-standing legal impediments were eliminated, media megaconglomerates came to be.

As the Internet rose in household penetration and in the delivery of multimedia content, the merger between AOL and Time Warner represented the first step toward channel integration. The prospect of a unified broadband future was just around the corner, according to many media technology and business analysts. Yet by any metric, the merger was a failure.

One could argue that the consumer success of the Internet was possible because the interconnection infrastructure was already in place. Just buy a PC and plug it into your phone jack and you were cyberspace-enabled. What few considered was the time and expense necessary to roll out a new broadband infrastructure to sup-port a multimedia Internet. So bad timing may have been the underlying cause for the failure to realize the vision.

But time has proven that the vision of a multiplatform, multichannel universe was correct. It just has taken longer than expected to get there.

Marketing revolves around brand awareness. Consumer loyalty and relationship-building require a constant presence of brand. This reality was so important to terrestrial broad-casters in the United States that after the DTV standard was adopted by the FCC, the ATSC developed an additional standard to ensure that after the analog shutdown and the relocation of channels to new frequency slots, viewers could still identify and navigate to programming based on the old analog channel number.

As broadcasters move into new delivery channels, customer brand loyalty can directly influence the success of any new channel. Advertisers can be offered a mix of presentation platforms with refined demographic characteristics. So, regardless of the fact that these new distribution channels have yet to turn a profit, they are absolutely essential to brand awareness.

TOWARD INTEGRATED PRODUCTION

The digitization of audio and video created an opportunity to easily exchange con-tent between consumer devices. Pristine copying has precipitated rights management issues, and preventing (or at least discouraging) unauthorized use is a defining factor in any content distribution strategy. No segment of the media industry wants to repeat the Napster fiasco that nearly destroyed then rewrote the rules of the music business.

Islands of production for each delivery channel have been the status quo for decades. Spinning off of a promo or tease from program material has been but a small part of broadcast operations.

To remain in that mindset is certain death for any content-producing organization. As this book will explore, today content producers, broadcasters, and distribution channel operators must think in terms of the big picture and leverage their production and distribution infrastructure to maximize usage and emerging new media revenue opportunities.

Linear platform-specific production

With the increasing need for compelling content to attract audiences, production and creative personnel are being taxed. The plethora of consumer platforms and commercial signage that must be supported has led to increasing demands on existing production personnel, workflows, and equipment. The answer is for organizations to do more with the same number of people. In other words, they must leverage digital technology and workflows for improved efficiency.

Faced with the large capital expenditures necessary to convert to digital production and broadcasting, it is easy to understand why there is a need for the design and implementation of integrated production systems. Linear, single-channel workflows and infrastructures will get the job done, but at a cost in time, effort, and expense that is not acceptable in today's business climate.

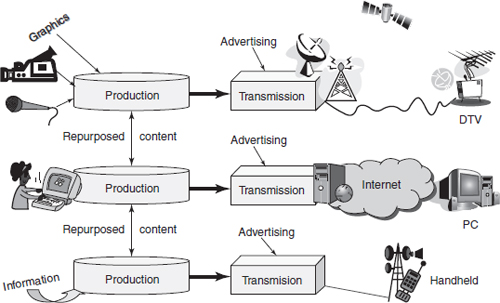

FIGURE 1.6

Independent production and transmission workflows for each consumer device

With the rush to get content distributed over new media channels, brute-force production assembly lines offered a quick solution. As shown in Figure 1.6, a discrete production process fed each delivery channel. Content was created and formatted independently for each reception platform. When the need arose to repurpose existing content for another delivery channel, existing clips and/or data were fed into the assembly line for the target delivery channel.

New outlets such as digital signage in stores and custom broadcasts to elevators, gas stations, and taxis are increasing the strain on production resources. This con-tent must also be converted to transmission formats that are compatible with diverse distribution channels and multiple consumption devices. Production requirements will only intensify as new platforms and delivery channels continue to come into existence.

Converged parallel production

Innovation is a given in the media business. New technologies that enable creative, business, and infrastructure enhancements are constantly sought. As the world went digital, so too did content production.

However, in many instances, existing linear production and distribution work-flows were maintained during the transition to digital production and multiplatform distribution. But as more distribution channels and more consumer reception devices appeared, the ability to reuse content on all channels became a driving design requirement. Those with foresight realized it made good business and technology sense to coordinate the linear processes. Why repeat common processes? The concept of integrated production was born.

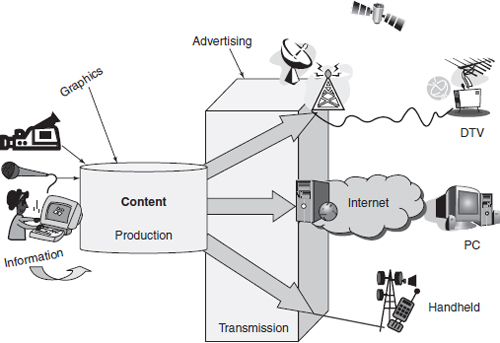

FIGURE 1.7

An integrated multiplatform production workflow

The key to integrated production is the identification of technology and work-flow overlap. Figure 1.7 presents a simplified view. There are quite a few production processes that are common to all delivery channels. Intelligent design of a production infrastructure will implement a system that can produce appropriately for-matted content for the transmission stage of the broadcast chain for each delivery channel.

Workflows for content production and presentation share numerous common processes. With careful analysis and thought, streamlined production that overlays the technical infrastructure can be developed.

A nonlinear world

Abandoning video and audiotape, TV production has moved to file-based production. This enables the simultaneous production of content in all the formats required for distribution over multiple channels. Cumbersome linear tape-based editing takes a lot more time than nonlinear editing (NLE).With a NLE workflow, more than one editor can access raw content at the same time. Keep in mind, digital copies are perfect, so production values remain pristine no matter how many generations of editing are performed.

Digital broadcasting has led to the influx of massive amounts of IT equipment in production infrastructures. PCs and media servers are everywhere in a Broadcast Operations Center. A PC running an automation program often controls program-ming and commercial insertion. Every aspect of production in all media businesses has been transformed by digital technology.

Because production must now support a wide variety of delivery channels for multiple devices, format conversion has become a huge issue. Transcoding and graph-ics compositing must be done on the fly, in real time, so that when content leaves a master control room, it is properly formatted for the delivery channel and can be presented on the associated reception device. This exacerbates the need to use common processes in parallel workflows in configurable, integrated production control rooms, and master control rooms.

Individual pieces of equipment and full system solutions that address integrated production, diverse distribution, and multiple receiver requirements are beginning to appear. Both professional and consumer content creation applications can generate audio and video formatted for television, Internet, and cellular channels.

Integrated production for diverse distribution channels to multiple devices isn't about working harder; it's about implementing technology and workflows that work smarter.

AN AUDIENCE OF CONSUMERS

There is seemingly no end to where digital media will be available for consumption— elevators, taxis, gas station pumps, and malls are but a few of the heretofore inaccessible places that media now reaches. It is safe to say that there is virtually no limit to where media will be consumed, save the requisite technology to get it there.

And viewers are not only getting content where they want it, but also when they want it. Today, time shifting is the norm for many viewers. Many television set-top boxes (STBs) have incorporated digital video recorders (DVRs). If a station offers five show times instead of one, will it add to or erode viewership? How will this impact advertising? If the audience is reduced by 10% for the first run, will it be offset by DVR viewing? Will commercial skipping cause advertisers to lose 10% of their audience? Can this be offset by Web rebroadcasts? Can technology disable commercial skipping? Is there a way to enable commercials-on-demand?

Advertising is about increasing brand awareness and sales. Any means to this end is the goal regardless of the media mix. This dilution of viewers could be offset by developing a personalized, targeted, multiple consumption device strategy. Viewers are directed from platform to platform for more interesting content. In a sense, this is a form of viewer relationship management.

These are business issues. Although profitable models have not yet been discovered, one thing is clear:All broadcasters must deliver content over all possible distribution channels and must try new approaches to revenue generation. As always, the ones who are most successful at adapting will survive.

However, there is a riddle to solve: What is the equation that will produce a favor-able value proposition for all involved? Like Oedipus and the Sphinx, if a media company fails to solve it, its competitors will devour it.

Just as in 2001: A Space Odyssey, where the planets aligned, the monolith was discovered, and humankind took its next evolutionary step, so too has the media business made a quantum leap into a brave new world. Digital technology is the monolith.

“The meek may inherit the earth, but only the bold will ever find heaven”

from “Opportunity Knocks”

by Phil Cianci copyright 1995 Iopherian Creations