Chapter 6

Planning the Production

Television has undergone many changes. One of the things that hasn’t changed is the need for thorough preparation. A good director or producer goes to the control room prepared.

Roone Arledge, television sports pioneer, former President of ABC Sports

The planning process is always much more time-consuming than the actual production process. In fact, some have stated that 99 percent of a producer’s time is spent planning or in preproduction, leaving 1 percent for the actual production process.

While the production process is the most glamorous part of the business, the planning phase is where the majority of the decisions are made. The purpose of the planning process is to review the various available options and prepare a plan that will provide the best television coverage of the event. The plan has to include both technical and production components. Planning for a small local event may take only a few days, whereas planning for the coverage for an event the size of an Olympic Games may take four or five years.

Creating goals for the production is an important step in the planning process. Once goals are determined, they provide a benchmark that can be used to measure the success of your television program. Television net work ESPN created the following series of television sports coverage goals that are exemplary.

Accuracy: Be informative while never compromising accuracy.

Fairness: Be fair in the coverage. Get both sides of the issues. Be objective.

Preparing to Cover Sports

How to prepare to cover sports:

- Know the rules of the sport

- Know the participants

- Know the venue/field of play

Decision areas:

- Cameras/lenses

- Graphics

- Mount-platforms

- Lighting

- Audio

- Medal ceremonies

- Start and finish protocols (run-ups/run-down)

How the production plan is created:

- Production planning meetings with group who will be producing that event

- Production meetings with production staff

- Meetings with international federations

- Sports events and test events at that venue (test lighting, graphics, etc.)

- Rehearsals right before the event

Adapted from Pedro Rozas, Head of Broadcast Production, multiple Olympics

Olympic Broadcast Production Goals

- Uncompromisingly fair and equal coverage of Olympic competitors

- Insightful, informed storytelling through appropriate shot selection and replay options

- Tight, expressive coverage of each athletic performance, combined with multiple action perspectives, both live and in replay

- Highlighting of the audio nuances intrinsic to Olympic sport

- Clear and informative graphic presentation

- Thoughtful coverage of medal presentation ceremonies

- Enhancement of the viewer’s appreciation for the athletes efforts and the drama inherent in Olympic competition

Broadcast Information Manual, Sydney Olympic Broadcasting

The primary goal of International Sports Broadcasting (ISB) is to produce a definitive story line in all broadcasts, meanwhile capturing the action unique to each sport using innovative camera angles teamed with dynamic replay sequences. This coverage is enhanced with a compelling audio plan designed with the express purpose of bringing the viewing audience as close to the action as possible. To meet this goal, ISB has aligned itself with an experienced television production team comprised of talented individuals who are passionate about their work and capable of producing exceptional TV coverage of these Games.

Broadcaster Handbook, Salt Lake Olympics

The 1956 Melbourne Olympic Coverage

For the Olympics we would often have three set-ups each day, and one of the problems was lack of camera cables. So we had a crew following behind to pullout cables and jump ahead to the next site. Because of the restriction on cable, production planning was a significant issue both for the ideal camera position and suitable link sites to get the signal back to the studio. Operationally, the van was packed with production and technical staff. Normally, the van functioned with seven crew, three CCU operators, an audio operator, technical director, producer and production assistant. As wellas this, during the Olympics extra staff—sporting personnel to identify the athletes—often stood at the back giving directions.

Barry Lambert, Technician, Van Out of Time

Analysis: Tell why and how things happened. Lend perspective to the events as they unfold.

Documentation: Capture the event, including the color, pageantry, and excitement. Help the viewer experience the event. Innovate in audio and video to show events from a new perspective.

Creativity: Develop storylines. Take the viewer beyond the obvious. Entertain and inform using a variety of methods (graphics, etc.).

Consistency: Maintain your level of ambition throughout the season. Do not become complacent. Do not fall victim to patterns that may diminish creativity.

Flexibility: Follow established formats, but treat every game as a new event.

(Condensed from ESPN/Catsis, Sports Broadcasting)

Coordination Meetings

Coordination meetings are essential to the planning phase of a production. These meetings provide a forum for all parties involved in the production to share ideas, communicate issues, and ensure all details are in line for the production. Coordination meetings will involve applicable sports organizations, venue management, television production personnel, and any other party involved in the production. By organizing these precompetition meetings, each group begins to understand each other’s role and the issues confronted by each. The meetings allow the various groups to work together for the best remote coverage. Relationships that are helpful to the production crew, when something goes wrong during the event, can be forged in these meetings.

The International Amateur Athletic Federation created a series of guidelines for television coverage of athletic events. One guideline clearly states the importance of a coordination meeting: “A coordination session well in advance of the event is absolutely imperative. All parties that may take an active role in the meeting should be present—television with all departments involved, organizers, timing, computers, telecommunications. All demands and wishes should be voiced, discussed, and resolved at this early stage. A long report of the planning session keeps all the involved parties informed of decisions. However, even the most careful preparation of the coverage of a one-day event is no insurance for a trouble-free show. It is necessary to be ready to act or react if cameras fail, if the computer breaks down, because the show must go on.”

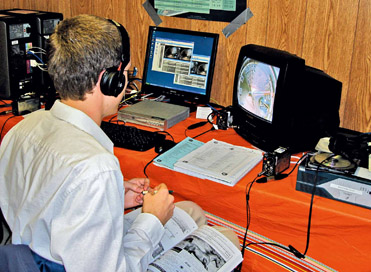

Figure 6.1

A venue survey team reviews a facility to determine potential broadcast issues.

Figure 6.2

Site surveys may include putting on skis and skiing the course. Here, a producer and director survey a mountain venue to determine the best camera positions

Remote Surveys

When discussing venue surveys I’m reminded of an old commercial that states: “You can pay me now, or you can pay me later,” meaning that while it seems expensive at the time, it will cost you more in the long run if you don’t do it. That’s the essence of surveys. .. sometimes they are expensive and seem a bit like a boondoggle, but they’re really the only way that your interests and costs can adequately be determined. You can learn more in an hour about the location and the organization than you could in a month of email and telephone calls.

Joe Sidoli, Director of Production Resources, multiple Olympics

The production team generally has a good idea of how the event will be covered. However, until the venue is visited by the survey team, final decisions cannot be made. The survey team is there to assess the venue and determine how, where, how many, who, what, and how much. The answers to these questions will provide the foundation for the production’s planning.

A remote survey, or venue survey, is generally completed far in advance of the event, especially for large-scale competitions. For an event such as the Olympic Games, remote surveys may occur four years in advance. A small, local event survey may occur as little as a week in advance. However, unless engineers are fully familiar with the facility, it is essential to complete a detailed survey (see Figures 6.1 and 6.2).

Leni Riefenstahl, on Filming the 1936 Olympic Games

After months of negotiating with different officials, Riefenstahl finally got permission to build two steel towers in the infield of the stadium. These enabled the cameramen to take good all-around panning shots and, with the telephoto lenses, some of the big close-ups Riefenstahl wanted. But wherever the cameras were put they seemed to block someone’s view and provide new objections. Eventually she was given permission to dig pits around the high jump and at the end of the 100 m sprint track. From these the cameramen could gain good low-angle images of the competitors without distracting anyone. The pit at the end of the 100 m track proved too close for comfort, and in one of the heats shown in the final film, Jessie Owens can be seen nearly running into it. The officials were furious and made the production team remove all the pits from around the track.

The shooting techniques used by Leni Riefenstahl have become standards for Olympic filmmaking and television coverage ever since.

Olympia, Broadcasting the Olympics

Horror stories abound about people who did not check the power supply or look at a venue at the correct time of day. The purpose of the remote survey is to determine:

- the location for the production;

- where all production equipment and personnel will be positioned; and

- whether all the production’s needs and requirements can be handled at the remote site.

Numerous people who may be involved in the remote survey include the producer, director, technical personnel from the remote truck company, site contacts, and, ideally, the lighting designer and audio engineer. It is important to visit the venue at the same time of day that the event will take place. This allows personnel to assess the lighting, hear the sounds at that time of day, and identify other possible distractions.

The Contacts

It is essential to establish who the event/venue contacts are early in the planning phase and how to reach them in case of an emergency. The crew may need access to additional power or restricted areas at any time. In this case, it is essential to be able to contact the appropriate personnel immediately to prevent a complete breakdown in the production (see Figure 6.3).

It is important to establish an alternative contact person as well. A contact list should be created identifying as many ways to reach the individuals as possible by office phone, fax, mobile phone, home phone, and email.

Also important is identifying the appropriate contacts for all aspects of the event—venue, hotel, credentials, catering, specialized equipment, mobile unit, electrician, generator company, security, golf carts, transportation, officials, satellite provider, phones, uplink truck, and possibly even the sanctioning body for the event. Contact lists can become long but are necessary, and should be distributed to everyone working on the production.

Venue Access

Without the correct access to the facility, the production can come to a grinding halt. The crew needs access to the venue so they can do their work before, during, and after the event. During the planning phase, the following access issues need to be addressed:

- When does the crew need access? Can they arrive very early and stay very late? Is there any procedure—for example, a special pass—that must be completed in order to move them in or out at odd hours? Do they have access to adequate parking? Can they easily get to their positions during the event? Can camera crews move in and out of locations during the actual production of the event?

- Do engineers have access to cable runs?

- Make sure that the mobile unit can be driven onto the location, especially if it is of the 15+ m variety. Are there any small bridges, low overpasses, or narrow roads that could cause access problems for large vehicles? Can the access route handle a more than 36,000 kg production unit?

- Where can the mobile unit be parked so that it is close to power, within cable length of your cameras, and not blocking traffic?

Location Costs

Every location has its unique costs. It is important to identify what those costs are in advance of the production:

- Are there costs for crew parking?

- Does space need to be rented in order to provide the amount of area needed for the production?

- Does anything need to be built or modified at the location?

- Are there any local ordinances that will affect the production? If ordinances limit the production hours or access to the facility, the budget may need to be increased to include additional days.

- Is additional insurance required by the city or facility?

- Are there permits that are required by the city, county, or facility? Facility management should know what is required. However, it may be worth checking with the local police department and/or fire department to make sure that the necessary permits are in order to park on public property or on a public street. Sometimes permits can take days to process.

- Are security bonds required by the city, county, or facility?

- What is the cost of housing at this location?

Electrical Power

Surveying the electrical power on location is essential. It is important to find out if there is sufficient electrical power for all the equipment being used and if anyone else is planning to share the power with you. Engineers should not take anything for granted and must make sure that all electrical outlets actually work (see Figure 6.4). During the electrical survey, it is important to determine the following:

- Where are the breakers? How will the crew access them?

- How many extension cords are needed?

- Is a portable generator needed? If shore power (power on site) is available, is a generator needed for redundancy (see Figure 6.5)?

Other Areas for Survey Consideration

Broadcasting an Olympics is like putting on a few Super Bowls every day for 17 days straight. It is an enormous logistical challenge and we have one chance to get it right. . .

John Fritsche, Vice President of Operations, NBC Sports

Food/Catering: Who is supplying the food, how many meals are required, and where are they going to set up the meals?

Lodging: How many rooms are needed and how close are they to the venue?

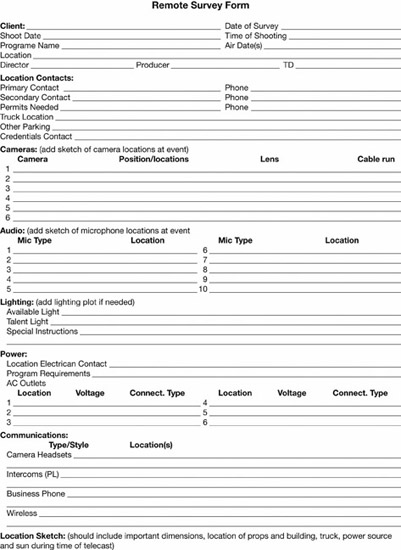

Figure 6.3

Sample of a small event remote survey form.

Parking: Is sufficient parking available for rental cars and golf carts? Parking should be marked on the location sketch.

Figure 6.4

Remote trucks require a large amount of power to operate. As a safety issue, only electricians should plug in/out this type of cable.

Figure 6.5

Generators are often required to be used by large production trucks due to the unavailability of needed power in some venues.

Security: Where should guards be? Do they need special parking? Where will they be located in inclement weather?

Transmission: Who will provide transmission services and where will their equipment be located at the venue? Do they have any special needs?

Construction: Does anything need to be constructed? If so, is there space allocated for the construction crew to build the required elements? Does the construction have any special needs?

Video and Audio Feeds: Who needs video and audio feeds outside the mobile unit? Are additional cables needed to meet the requirements?

Internet and Telephones: How many lines are required? Where should the lines be installed? How many cellular phones are needed? Are any dedicated lines required?

Medical: Are there medical facilities at the venue? Is there a hospital within close proximity? Is there a first aid kit nearby for minor injuries? Does an ambulance need to be nearby? If so, where would it be located?

Program Transmission

We seem to be at the end of baseband video as a way to move images and sound. As the signal flow becomes IP-based and trucks are connected to studios, they can move signals in a much different way.

Jerry Steinberg, Vice President, Operations and Technology, Fox Sports

Knowing how you are going to transmit the final production significantly impacts the planning process and survey of the venue. Line-of-sight transmissions may need to take place,

Roone Arledge, Production Innovation

In 1960, Roone Arledge (1932–2003), former president of ABC Sports, wrote a production plan for how he thought American football should be covered by television. His innovative plan included previously unheard of suggestions, such as directional microphones, handheld cameras, isolated cameras, game analysis, split screens, and the use of prerecorded interviews and stories. His ideas intrigued the network’s programming and sports directors, who allowed him to begin experimenting with his ideas. Since those early days, Arledge has been credited with transforming sports coverage. He introduced “instant replays, slow motion, advanced graphics, as well as the introduction of journalistic values and the personalization of athletes to sports broadcasting.” Dick Ebersol, an Arledge protégé who later became president of NBC Sports said, “Before Roone Arledge there were no replays. There were no slomo machines. There was absolutely no prime-time sports on any network. He encouraged others to see the unscripted drama in sports.”

When asked how he determined when to use “electronic wizardry” in his sports coverage, Roone’s response was, “The answer is simple: You must use the camera—and the microphone—to broadcast an image that approximates what the brain perceives, not merely what the eye sees. Only then can you create the illusion of reality.” His example was an auto race where, even though cars may be traveling over 200 mph, the perception of speed is absent when a camera with a long shot is used. However, when a POV camera is placed much closer to the track than spectators would normally be allowed, the close camera and microphone give the television viewer the sensation of speed and the roar that a live viewer would perceive by sitting in the stand. “That way, we are not creating something phony. It is an illusion but an illusion of reality.”

CBS Sports President, Sean McManus, says that Roone’s “greatest accomplishment was his ability to tell a story. He understood that to get someone interested in gymnastics, trackand-field, auto racing, and even the Olympics, the viewer had to care not just about the score, but perhaps more important, about the athletes themselves. It was Roone’s keen sense of storytelling and his ability to make even the most unknown athletes fascinating and compelling that truly separated Roone from all the other sports producers who came before him.”

satellite dishes may need to be installed, or special Internet access may be required. Today, there are quite a few ways to get the video image to the distribution point:

- Coaxial cable: Can be used for relatively short distances but is more susceptible to outside interference.

- Fiber optics (optical fiber): Video signals can be transmitted up to 16 km on a fiber optic cable with virtual immunity to interference. Fiber cable has a high capacity for transmitting information. In addition, it does not leak and can withstand temperature variations. The cable is very small and lightweight, low in cost, and very reliable.

- Microwave link: Microwave transmissions use radio frequencies (RF) usually in the super high frequency (SHF) band and must be line-of-sight; snow and rain can degrade a video signal that is transmitted by microwaves. The microwave transmitter has a highly directional signal with a maximum transmission of approximately 120 km. However, a series of repeaters can be created to transmit the signal around obstacles or increase the distance. Microwave transmitters can be handheld and can be so small that they fit on the top of a camera for short distances (see Figure 6.6). For long distances, the transmitter is generally moun ted on a vehicle or a building (see Figure 6.7). Sports coverage sometimes neces sitates the use of a moving vehicle (helicopter, boat, motorcycle) to transmit live video images. Since it is very difficult, or impossible, to keep a normal transmitter/receiver aligned, these vehicles are equipped with special omnidirectional transmitters that transmit to a modified dish that can receive signals over a broad area. Today’s transmitters/receivers have been programmed to automatically align themselves for maximum quality (see Figure 6.8).

Figure 6.6

The camera in the top photo is equipped with an RF transmitter. The lower photo shows the dish that is used to receive the signal.

Source: Camera photo courtesy of RF Central.

Figure 6.7

Microwave trucks are often used to send RF signals a longer distance.

- Satellite links are optimal when working in a remote site since they overcome the distance and line-of-sight problems. The transmitter “uplinks” the signal to the satellite. The satellite receives the signal, amplifies it, and then “downlinks” it back to the receiver. Satellite transmitters for multicamera sports productions are often mounted onto trucks (see Figure 6.9). The satellite signal is received by a satellite “downlink” dish, which comes in a variety of sizes (see Figure 6.10).

- Internet/Webcasting is a rapidly emerging transmission method that streams audio and video on the Web. Technology has improved to the point that broadcast quality can be obtained. French broadcaster TDF was able to stream live 4K Ultra HD from the 2014 French Open using Internet-based technology (see Figure 6.11).

- 3G/4G uplink is a growing technology that some see as a less expensive alternative to the satellite. Systems can be small enough to fit on the back of an individual camera. These systems are able to broadcast live with a professional-quality picture from almost any location.

It is also possible to use multiple video and audio sources together. This could include any combination of the above. For example, someone could be using the Internet from one site, a microwave unit from another location, and wired cameras at the field of play (see Figure 6.12).

Figure 6.8

Euro Media France used an advanced RF technology to transmit the 2014 Tour de France. The motorcycles provide an up-close view of the race action.

Source: Photo courtesy of Sports Video Group.

Figure 6.9

Satellite uplink truck.

Figure 6.10

Satellite receiving dishes.

Figure 6.11

Webcasting a sports event for NBC.com.

Figure 6.12

It is possible to link multiple video sources together. In this situation, a helicopter is transmitting an aerial view using microwave while the camera operator is using a wired camera. The two video signals are mixed, using a small switcher in the van, transmitted using a satellite uplink dish, and then relayed back down to the production facility.

Other Areas that Significantly Impact the Survey

There are a number of areas that need to be considered for both the remote survey and planning the production. The next few chapters will deal with these areas, including cameras, lighting, audio, and graphics. All of these need to be thought through before completing the final production plan.

Location Sketch

The location sketch is used to help staff identify camera, microphone, cabling, crew parking, and truck/office placement. As the name implies, the location sketch is not a refined drawing. Rather, it is a rough map of the remote telecast locale. The location sketch for an indoor remote production should include:

- room dimensions;

- furniture;

- props;

- talent broadcast locations;

- window locations; and

- power sources.

An outdoor remote location sketch should include:

- location of buildings;

- talent broadcast locations;

- compound location;

- power source; and

- location of the sun at the time of the telecast.

Backup Plans

It is imperative to have a thorough backup or redundancy plan in place in case something goes wrong with the production. Most production companies make sure that they have backup equipment, generators, graphics, and even a backup audio feed. When developing the backup plan, it is important to determine how the plan will impact space requirements—for example, where the additional generator will be parked.

302 disciplines / 38 sports + digital OB vans ×18 cameras + explosion of the cost of broadcasting facilities – best ever TV coverage + 40 billion viewers × global economic downturn + 40 venues / 3,500 employees – shared crews / venues / equipment + logistics expenses × 3,700 live transmission hours × less is more + quality = budgeting of the Athens Olympic Games.

Anna Chrysou, Deputy Producer, Athens Olympic Broadcasting

Joe Maar, Television Director, stated that: “Sometimes, it’s even important to have a backup for your backup plan. For example, some networks have one primary and two backup systems to get the game clock on the air during a sporting event. Their primary system is a direct cable connection to the stadium’s scoreboard clock, the secondary system is a visual recognition system that changes the character generator clock with the scoreboard clock. A dedicated camera shoots the scoreboard for the recognition software.”

It is not uncommon to have backup transmission equipment actually transmitting the same program on different systems. That way, if something happens with your primary transmitter, the production still gets to the intended distribution source. Although backup plans may seem like an unnecessary expense, if a problem occurs you will have saved yourself the cost of losing the production.

Interview: Tom Cavanough, Vice President Production, NASCAR

Briefly define your job.

I’m responsible for content in all NASCAR on SPEED programming.

What do you like about your job?

Creating and participating in a collaborative environment that promotes creativity, communication, and acknowledges the breadth of talent and experience of the people I work with. Focusing on the ability to fail and then recover rather than playing it safe or avoiding mistakes quite often delivers a very successful operation. In the broadcast business, the ultimate goal is to have that successful operation show up on the screen in the form of compelling content.

What are the types of challenges that you face in your position?

Habits are the toughest thing to break and they are even more difficult to change when people don’t even realize they have formed a habit. So, change can be a big challenge, but if you focus on giving feedback and developing a collaborative environment substantial change will take care of itself.

How do you prepare for a production?

It is important to make sure the obvious questions are asked and that typical assumptions are addressed. Stepping back and identifying the big picture storytelling elements helps to set up. .. everything.

- What is the storyline?

- Who are the stars?

- Who is the underdog?

- Where is the rooting interest coming from for the fans?

Productions really end up being quite simple because good stories are usually fairly simple, but we can get too “inside” and forget to tell the basic aspects of the story.

What suggestions or advice do you have for someone interested in a position like yours?

Follow your passion and let your ability develop because you will usually be surprised by the potential you have when you find yourself in “your element.” You will know when you find it and basically you should never stop looking for it.