Chapter 12

The Production

Content is still king. Technology is a secondary thing for us. The responsibility of documenting—creatively, emotionally, journalistically—the games itself is really our goal.

Craig Janoff, Director

Producing the Remote

There is no set worldwide programming strategy formula for producing a successful television remote production. NBC’s Olympic Games coverage primarily consists of packaged programs on the main network. Other countries primarily program live, staying away from prepackaged or delayed programming.

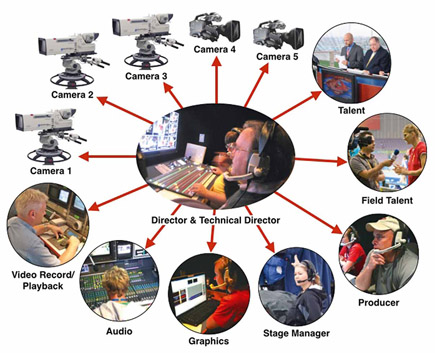

Figure 12.1

Each producer and director must determine the best programming strategy for their specific audience.

Better Than Being There

One thing that television does exceptionally well is take you to places that you can’t get to otherwise. By placing cameras in a variety of locations throughout the stadium, and having some of them fitted with very long lenses, we were able to achieve an intimate view of the players and the game that you just can’t get from a fixed seat location in the building.

Andy Rosenberg, Coordinating Director of the NBA on NBC

At an IOC Olympic television symposium, Yosuke Fujiwara, former Senior Producer for Olympic Operations at NHK in Japan, made the following statement: “We believe that the essence of the sports broadcast lies in live coverage. .. we believe that the unscripted drama exists in sports itself, and live broadcast is the best way to show such drama.”

Each producer and director must analyze their audience, the sport, and the available broadcast facilities to determine the best programming strategy for their specific audience (see Figure 12.1).

Several coverage strategies will be discussed in this chapter. Coverage strategies are constantly evolving, changing with the type of sport, the anticipated audience, and the skills of the crew.

NBC’s Olympic Television Philosophy

NBC’s broadcasting philosophy was born out of hundreds of hours of research, examining the preferences, expectations, and hopes of thousands of Olympic television viewers in the United States. Throughout the research, many of the same themes kept surfacing—story, reality, possibility, idealism, and patriotism. These five themes—which correspond to the five Olympic rings—serve as the foundation of the NBC Olympic television philosophy.

Ring 1: Story

Viewers want a narrative momentum, a story that builds. Stories make connections with reality, among facts, and between the subject and the viewer. This is what the viewer takes away from the telecast.

Ring 2: Reality

Perhaps the major hook for Olympic viewers is the unscripted drama of the Olympics, the idea that anything can happen, both of an athletic and a human nature. People look for real stories and relativity, things that apply to them. They are looking for real life and real emotion presented credibly.

Ring 3: Possibility

This ring covers the feeling of self-realization. The audience experiences the rise of individuals from ordinary athletes and their humble beginnings to their joining of the company of the world’s elite. This identification reinforces belief in their own ability to achieve. This embodiment of possibility gives the viewer a reason he or she can make it through.

Ring 4: Idealism

The Olympics are still viewed by a vast majority in the contexts of purity and honor. They appeal to what is best in us. This area summarizes the viewer’s need to integrate the intellectual and the emotional.

Ring 5: Patriotism

Love of country is not just limited to an American viewer’s love of the United States. National honor and Olympic tradition seem to go hand in hand. The viewer recognizes the love of his or her own country, but, at the same time, respects the international athletes’ love of their nation as well.

NBC’s Coverage of the Games of the XXVI Olympiad

Directing the Remote

Portraying passion and teamwork is key in covering sports.

Joseph Maar, Director

The director’s goal at a sports event is to:

- Build the viewers’ excitement about the event.

- Reveal relationships and educate the audience about the intricacies of the sport.

- Catch the ambience and emotion of the event.

- Communicate the event with clarity.

Types of Sports Action

(By Harold Hickman, Directing Television, (c) 1991, McGraw-Hill, Inc., reproduced with permission of the McGraw-Hill Companies) Whatever the sport, we can divide coverage planning into three variables the director should understand: (1) action flow; (2) team versus individual sports; and (3) horizontal versus vertical versus circular action.

Action Flow

Action flow concerns the continuity of action within the sport. Is there a constant flow, or is the action periodically interrupted by timeouts? In hockey, for example, the action is continuous, with few breaks. The ending of the periods or the stopping for face-offs may be the only interruptions. Soccer is another such game. On the other hand, American football involves very sporadic action. There is a break after every play. Each actual action is condensed into 10 or 15 seconds of intense physical conflict followed by approximately 30 seconds of time-out. Golf action is also very slow and sporadic. A shot may last only 5 to 10 seconds, while time spent in walking, club selection, scouting, and preparation add another five minutes or more per player. Action flow can thus be divided into two categories: stop-and-go and continuous action.

Stop-and-Go Sports

Stop-and-go sports tend to be rigorous and involve a great deal of physical contact or energy exertion. Golf, perhaps, is the single exception. The chief stop-and-go sports covered by television include football, baseball, tennis, golf, bowling, and track and field (see Figure 12.2). All of these sports involve emotionally intense action followed by some period of inactivity.

Figure 12.2

Stop-and-go sports involve emotionally intense action followed by some period of inactivity.

Source: Photo by Andrew Wingert

Directing Stop-and-Go Action

From a production and directing standpoint, the need to maintain audience interest during time-out periods is the primary challenge. Pauses in action are frequent and sometimes very long (at least from the viewers’ standpoint). Replay devices have provided an excellent production value for such periods. The longer the “stop” periods or the more complex the action, the greater the need for replay units to provide isolation of and different angles on the same action.

Directing a Remote Production

The first-time observer of a remote production may perceive that all is chaos. However, you can see the large number of interactions that need to take place for the director (not even counting the producer) in a simple five-camera sports production. This chart does not include engineering, logistics, and all of the assistants that many of these positions include.

Tips for the Technical Director When Switching on a Remote

- Make sure that every camera operator knows what you want them to do before you begin the program. They should consider themselves “live” allthe time. That way, if you mis-switch, you may not look bad. If the operators have a basic game plan, you will not have to keep telling them what to do.

- Study each monitor carefully before you switch to it. Even though the director may be screaming “take camera two” and camera two is out of focus, he or she may be confused and really mean “take camera one.”

- Use allyour fingers on the switcher keys. It is much faster to cut quickly between cameras if you already have your finger on the button.

- Try to anticipate what the on-camera person may do before you switch. When in doubt, cut to a wider shot. Always have at least one camera on a wide shot at all times.

- Try to develop a switching or cutting cadence to your shots. If the action is speeding up, cut faster between cameras. This establishes a rhythm.

Adapted from Ten Steps to a Better Remote Switching

The use of analysis for such events is also essential to maintain the tempo of the production. To sustain viewer interest, it is wise to include sophisticated analysis of the athletes’ performance, such as the following: blocking, running, passing, and all elements of defense in football; hitting and fielding form in baseball; form and agility in tennis; and form in golf and bowling.

1992 Barcelona Olympic Games Opening Ceremony

For the Opening Ceremony the production team used four control rooms at the Olympic stadium. One of them was used for the coverage of the Athletes parade and the choreography and movements of the actors on the stadium floor, using the signal from 16 cameras (half of which were mobile). A second control room received the images of seven cameras aimed at recording the reactions of the dignitaries box and the public, as well as on the speeches podium. Ten cameras, coordinated from a third control room, covered all the action that took place on the stage at one end of the stadium. And a fourth control room, under the command of the director of television production of the ceremony, was responsible for the synthesis of the program with the aid of panoramic shots from cameras located in unusual positions (beauty cameras), such as a helicopter or a crane.

Television in the Olympics

Directing Emphasis on Scoring

The director must be able to even out the emotional highs and lows of the stop-and-go game. Obviously, the coverage of the action is relatively simple—follow the bouncing ball. This means that the director must frame the action in the physical direction of its flow. Most action in stop-and-go is offensive action —that is, the individual or team on offense is the center of the directing concentration. Normally, the team on offense is the only team that can score. A team may intercept a ball (or puck), but that team is immediately on offense. The concentration is on scoring, and therefore the director’s responsibility is to follow the team that has the greatest opportunity to score.

Television Sports Clichés

- The camera will always show some fan holding a poster that uses the network’s initials to spellout a phrase about the home team.

- If the television camera locates a significant spectator—an owner or parent/spouse of a coach/player—you can be sure those folks will get an excess amount of camera exposure during breaks in the action.

- Late in a night game, viewers will get a close-up of a baby sleeping in the stands.

- After a player makes a critical error late in a game that guarantees defeat for his team, the camera will zoom in on his face as he sits alone on the bench.

- If a team is about to lose a game that eliminates them from the playoffs, the camera will lock onto any player sitting on the bench with his face buried in a towel.

- Immediately at the conclusion of a championship football game, the winning coach will have a large container of water or sports drink dumped over his head. The TV audience will then watch slow-motion replays of this event from multiple angles.

Mike Hasselbeck, Writer

In baseball, we have a single player (the hitter) against an entire team. Coverage of defense is a much larger item than coverage of offense. After all, the whole playing field is filled with defensive players and the hitter is even standing out of bounds while in the batter’s box. Yet, despite the fact that the main focus of baseball is defense, most of the coverage is of the offensive play (the hitter against the pitcher).

Tennis may also be considered an exception to the “only the offense can score” situation. Here, either player can score—both are on offense. But the serving player has a marked advantage, since he or she has the first offensive opportunity. Each time the ball passes over the net, the offense shifts (see Figure 12.3).

Maneuvering the team or player into position to score is the aim of the play in stop-and-go. This is normally accomplished through a series of “plays.” The closer the team or player gets to scoring, the more intense the game. The director can enhance this emotional involvement by warming up the coverage—that is, tightening the shots as the emo tional level of the production increases. It also means adding more radical shot angles and increasing the intercutting of shots. The pace of the production needs to pick up as the emotional level of the production increases. This enhancement of the emotional level helps the audience grasp the pressure of the sports performance.

Figure 12.3

Tennis may also be considered an exception to the “only the offense can score” situation. Here, either player can score—both are on offense.

Pumping

To enhance an otherwise dull sport performance, the director may want to pump the game through the use of additional production values that may be viewed as unethical by some. Any attempt to make a game or contest appear more exciting or tight (in terms of who will win) can be viewed as beyond the presentational responsibilities of the director. Some viewers may want the director merely to provide adequate coverage and let the viewer decide whether the game is exciting or dull.

But the director’s goal and responsibility is to make the production interesting and entertaining for the audience, so there is a very basic objective to be met in the use of increased production values toward that end. How far to go with the introduction of additional production values so as to achieve this end must be determined before the production begins. Obviously, it is questionable whether to allow the announcing talent to pump up the closeness of the conflict through false excitement in play-by-play and color presentation (analysis of game strategy or quality of individual performance), and to augment this with exciting, fast-paced production when the score is 50 to 0. The new director may want to observe the techniques of a seasoned television director faced with coverage of a game that is lopsided in score or athletic match or performance.

The addition of more shots of the crowd (including people with painted faces and bizarre masks or sleeping babies) that are not part of the game or contest will help alleviate the boredom of the game without pumping. Interesting activities on the sidelines can also be included—a worried coach or an injured player. Basically, anything of interest that can divert attention from the slow moving game itself will help maintain the attention level of the audience. Stop-and-go sports make this type of coverage even more difficult and essential.

Continuous Action Sports

Unlike stop-and-go sports production, the continuous action contest provides little or no time to interrupt for color analysis. Continuous action sports include basketball, hockey, and soccer. Generally, these sports have not been as popular as stop-and-go performances on American television, because they do not provide the natural breaks for commercial insertion or for the audience to take a break in their viewing to do something else. The single exception is basketball (both pro fessional and college level). Basketball can be considered a basically continuous action sport. There are no breaks between field goals, although there are more breaks in basketball than hockey or soccer. Action stops in basketball for fouls and team time-outs. During the extended stop for a foul, one or more replays of the foul can be shown and other comments made. These are really semistops, because the game does continue and there is little time for commercials or extended replays.

Director’s Slang

The following are some of the slang words used by directors:

Effect:Switcher cue term for animation, box, or special effect. Fly:A non-switcher effect that is generally created by a digital effects generator (DVE).

Go wide: Zoom out.

Go close: Zoom in.

Get tight: Zoom in very close.

Mix: Mix cameras without a full dissolve.

Pull focus/rack focus:Change the focus from one subject to another.

Push in: Zoom in.

Pull out: Zoom out.

Transform: Animated graphics.

You’re hot: Your camera is on.

Continuous action sports tend to be very rigorous and are usually limited to a specific, bounded playing area. In the cases of basketball and hockey, these areas are rather small, which increases the emotional potential of the game for a television audience because the crowd is close to the playing area and be comes more emotionally involved with the play.

There are other continuous action sports, minor from a television standpoint, including cross-country or marathon races. The Boston and New York marathons are considered major sporting events, especially by runners and by residents of those cities. But not much television time is given to marathons compared to other continuous action sports events. Track-and-field events generally do not fit into this category, because the various events, considered as a single coverage, involve a great deal of stop-and-go.

Alexandro DeMartino, Director, Sky, Italy

- Favorite sport to direct: Football.

- Quote: “For me directing is like a conductor and an orchestra. Single work of each camera means nothing. .. together they can make something.”

- How do you prepare for directing? A good director must understand the rules of the sport and must be physically ready.

- Advice: Be diplomatic, know finance, audio must be at the same quality level as video. Graphic operators need to not only understand the rules of the sport, but must be able to predict what is going to happen in order to have the correct graphics together.

Gary Milkis, Director, NBC and CBS, United States

- Favorite sport to direct: Downhill skiing.

- Quote: “Directing is telling a story with cameras.”

- How do you prepare to direct? Design the monitor wall so that it makes sense for the sport.

- Advice: Find a balance between pushing the crew and not abusing the crew. Have a little fun on the headset.

- Biggest challenge: Locating the best camera positions.

Greg Breckell, Director, CTV, TSN, and ESPN, Canada

- Favorite sport to direct: Golf.

- How do you prepare to direct? Complete a detailed survey of the course.

- Advice: Know the game, not just the rules. Properly motivate the crew member who may not feel that their job is as important as others.

- Biggest challenge: Communication and coordination of game plan. Everyone needs to understand what is going on and why. Simple things are what can really hurt a production.

Brian Douglas, Director, over 700 NBA games, United States

- Favorite sport to direct: Basketball.

- Quote: “Know the sport and the people. How a player dribbles the ball can tell you if he is going for a three pointer.”

- How do you prepare to direct? Research is key, look at recordings.

- Advice: Establish a creative environment to work in. Keep in mind that you are there to make others look good, not you. You are not part of the show.

- Biggest challenge: Maintaining control of the situation.

Bai Li, Director, Shanghai TV Sports, China

- Favorite sports to direct: Table tennis and basketball.

- Quote: “Have creative new ideas when covering traditional sports. It is easy to do it the old style.”

- Advice: Know the sport. Watch a lot of sports.

- Biggest challenge: This generation is not used to working as a team. The Chinese director must spend more attention on building teamwork and fostering good communication.

Mark Wallace, Director, BBC and LiM Africa, United Kingdom

- Favorite sport to direct: Rugby union.

- Quote: “The five P’s of sports television: Prior Preparation Prevents Poor Performance!”

- How do you prepare to direct? Go around the crew, introduce myself, talk to each member of the crew and explain what I would like them to do. Then get clearly in my own head what needs to be done and when.

- Advice: Try to appear calm and in control of yourself. Have a backup plan and try to always think one step ahead.

The director must take into consideration a number of factors when preparing to cover continuous action sports: (1) rapid camera action; (2) increased shot sizes; and (3) camera changes during action.

The Image

It is not the number of cameras that determines the quality of the picture, it is the quality of the perspective. We can learn a great deal from the old masters such as Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, Goya, Rubens or Rembrandt. Their pictures had a strength of the middle. They have a center of concentration, which catches the eye involuntarily. This strength of the middle is also possible in the moving picture, where the eye is guided to the focus point and can rest quietly. Unfortunately, it is missing in many cases.

Horst Seifard, former Director of Sports Programs at ARD, Germany, Television in the Olympic Games: The New Era

Camera Action Tends to be Rapid

Shot size usually is rather a wide angle to give the audience a chance to see the relationship of offense to defense and offensive player to defensive player, and to establish the relationship between the ball, the team on offense, and the goal. Still, to increase the warmth of a game, the camera shot needs to be as close as possible.

Increase in Shot Size

As the speed of the action increases, there is a tendency also to increase the size of the shot in order to include all of the action. However, as action speed increases, the director really should attempt to tighten shot size to capture the emotion of the faster pace. In basketball, for example, the intensity of the action increases as the ball is worked closer and closer to the basket. Camera shot size should get closer and closer. This does two things: (1) it increases the warmth of the coverage and the emotional involvement of the audience; and (2) it gives the audience a better perspective on the action.

This is especially critical in hockey, where the puck is so small and moves so fast that it is difficult for the audience to see and follow it. As the play moves across the blue line and closer to the goal, the camera coverage should move closer to the play.

Camera Changes During Action

A basic rule in sports coverage is to never change from camera to camera when critical action is taking place in the playing area. In basketball, this means the director should not change from camera to camera when a shot is in the air (either a field goal or a free throw). In football, this means the camera covering a quarterback who is fading back to throw must cover the flight of the ball until it is caught or incomplete. To change camera angles at these critical times requires that the audience re-establish their relationship to the game from another angle. This only takes a second to do, but becomes critical in the split second involved in the pass or the shot. The same critical point occurs in baseball when a pitcher delivers to a batter.

The director must be careful during continuous action sports not to over-direct the coverage. Often a single shot of a mile run, for example, will satisfy the audience, because they are interested in the continuity of the event. Only when the race comes down to the final 100 yards or so should the director attempt to increase the suspense and emotional involvement of the audience by zooming in on the lead runner (or runners).

Team and Individual Sports

Sports coverage can also be planned from the standpoint of the number of athletes involved. Most television sports are team sports (football, basketball, baseball, hockey), but for a number of years there has been a growing interest in individual sports (tennis and golf).

Team Sports

We are obviously spending too much time covering the line-up, the race, and the results, rather than the emotions of the competitors and taking the viewer behind the scene.

Alan Pascoe, Managing Director of Fast Track, UK

With team sports, there is a built-in interest because of the complexity of the teams working together (see Figure 12.4). Most avid sports fans understand the sophistication of various games and appreciate the role of various team members and their contribution to the team’s success (or failure). For example, the offensive line of a football team should be made up of players highly skilled at their specific positions. Fans (and replays) may want to concentrate on the efficiency of these players as they carry out their assignments. This increases the attention factors for the viewer, and thus the excitement of the game. In most team sports, the ability of the team to work together as a well-organized and effective unit provides unusual coverage opportunities. It also, however, increases the demands on the director to understand the game and the complexities and fine points of quality play. Because of these complexities, coverage of team sports is more involved than for individual sports.

Individual Sports

Individual sports, on the other hand, have their advantages (see Figure 12.5). There is a greater opportunity for the director to increase the emotional level of the production by concentrating on close-up production techniques. It is easier for the audience to associate themselves with an individual player than with a team of players. This involvement is inherently greater if the individual is in a contest with another individual (tennis) than if he or she is in a contest with him or herself (golf).

With individual sports, the director has a greater opportunity to warm the production through the use of close-ups and single shots. Examples include tennis, boxing, skiing, track and field, golf, and wrestling (real or exhibition).

The director of an individual sport’s coverage has a number of considerations: (1) building emotional involvement through tighter coverage; (2) dealing with the dominant player; and (3) limited space for coverage.

Building Emotional Involvement

The director has an opportunity to build the emotional involvement of the audience by increasing the warmth of the production. The director can get inside the personal space of the individual in the shot and draw the audience in. He or she can develop a visual situation in which the audience member can relate to the athlete and feel the pain, pressure, and thrill of victory or agony of defeat.

Dealing with the Dominant Player

If the sport provides a conflict between individuals (such as tennis or boxing), coverage may concentrate on the dominant player. This may not always be the winning player. For example, a loser who is suffering from injury or losing control of a match may be the story the director wants to cover. American audiences have a natural affinity for the underdog, and this can be translated into interesting coverage if the underdog is attempting to upset the star. Because the player in these contests usually has fans, the director needs to balance the coverage of each player so the fans will be satisfied. Of course, the director can build audience interest and loyalty by the type of coverage given. It is relatively easy to slant the coverage toward one player or another in an individual sport. But the director should try to avoid this. If the coverage takes more shots or tighter shots or better angles of the favored player, cuts away when the favored one is in trouble, shows the dis-favored player when he or she is in trouble, or slants the comments from play-by-play or color commentators, then the production is slanting the coverage unethically.

Figure 12.4

Team sports have a built-in interest because of the complexity of the teams working together.

Figure 12.5

The director has a greater opportunity to warm individual sports production through the use of close-ups and single shots.

Softball Coverage in 1945

It was necessary to shrink diamond dimensions for proper perspective. Two cameras covered the game. One was set up behind home plate, the other at first base looking toward second. A 12-inch (30.5 cm) ball was used instead of the standard ball, again to limit action, to keep flies in close, keep hits from going over the fence.

Television Show Business

Monday Night Football, ABC Sports

The Monday Night Football influence of long lens close-ups, greater quarterback coverage, and increased field level shots have enhanced football by providing mythic images of modern gladiators engaged in both sport and spectacle.

Joseph Maar, Director

The director should try to be as journalistic as possible in these situations. He or she should provide balanced and fair coverage of all contestants. This is often difficult when covering the game for a local high school or college against an arch rival from the next town and even more difficult when covering the United States team in Olympic competition. Balance in camera coverage and the establishment of a strong coverage formula will help reduce the possibility of slanting coverage.

Limited Space for Coverage

Individual sports normally have a very limited space that must be covered. You may argue that golf is not limited at all—as a matter of fact has one of the largest playing fields in sports. But we are talking here about the area in which the athlete must work at any given time, not the total field of play. At any point in the round, the golfer is dealing with a small tee area, a bunker, or a green—not the whole golf course. The marathon runner also is dealing only with that space in which he or she is running at the time—not the entire course. In team sports, this area is greatly expanded because the team can take up a great deal of area (field or court).

The bowler deals with only a single alley, the tennis player works with a relatively small court, and the vaulter deals with two standards, a bar and a short runway. This provides the director with a great deal of flexibility and opportunity for intensity in coverage. Golf and racing (marathons and auto) are perhaps the exceptions, for the director must be prepared to cover wide areas but concentrate on small play areas at any given time. POV cameras and small transmitters have greatly aided such coverage.

This limited working space provides increased warmth to coverage of the individual sport. Because the director can concentrate more cameras on a smaller area, there is the opportunity to tighten shots and to mix angles for more effect. The director who fails to make use of this opportunity will find the coverage becoming dull and cool. For the individual sport to compete with team sports on television, the drama of the contest and the struggles of the athletes must be portrayed. The director is involved in telling the story of the conflict. Anything that can be done to make sure the audience understands the real story should be done.

All productions have some type of axis. In most sports, this axis is critical to the orientation of the audience. With few exceptions, sports coverage can be divided into three types: (1) horizontal action; (2) vertical action; and (3) circular action.

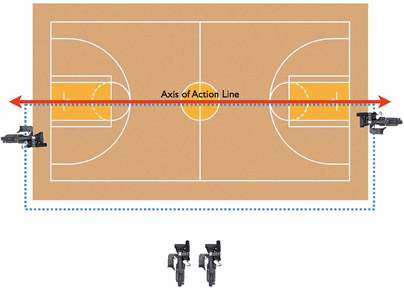

Horizontal Action

Fortunately for television directors, most sports contests are horizontal in nature; that is, the action takes place on a horizontal plane in front of the cameras (see Figure 12.6). Football, for example, is made up of two teams moving up and down the field across the screen. Basketball also is a contest of two teams moving up and down the floor in front of the cameras. Unfortunately for the director, such action violates the z-axis rule—it is better to have action toward and away from the camera than across the screen. But since the orientation of the audience to the game is horizontal, this dictates the type of coverage you must use.

The director can take advantage of the ease of establishing cameras in horizontal games by drawing the imaginary axis down the middle of a football field, from goal post to goal post, and down the middle of the basketball court, from backboard to backboard. If during action all cameras are kept to one side of that line, it will be easy to keep the audience in the game.

Cameras can be located within the end zones or under the backboards in a horizontal contest. But if coverage of play extends beyond those points and crosses the axis, the audience will become disoriented. Cameras can be placed in these locations for color and for some time-out coverage, but they should not be used extensively for coverage of plays. The single exception, noted previously, is their use for reverse-angle replays. In these cases, the audience must be re-established through a statement from the announcing crew or from a graphic on the screen indicating that the replay is from the opposite side of the field of play.

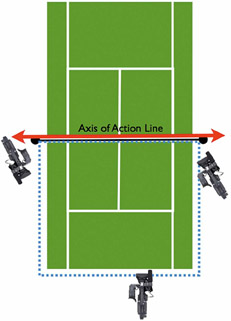

Vertical Action

In horizontal games, such as tennis, the director must treat the action as if it were vertical (see Figure 12.7). The movement of the ball and the action of the players makes it difficult to provide general coverage in the horizontal camera setup. In these cases, the z-axis becomes a major factor. The director attempts to make the movement of the ball function within the z-axis, moving toward and away from the camera. In tennis, for example, cameras set up for coverage from one of the baselines show the ball moving from one player (with his or her back to the cameras) to another across the net (facing the cameras). It makes little difference which baseline is used, since the players exchange sides of the net throughout the match. In this case, although the game is horizontal (across the net from court to court), the coverage is vertical (toward and away from the cameras). Since tennis is a stop-and-go game, sideline cameras can be used for “stop” coverage, with closeups of players and fans.

Golf, on the other hand, is a purely vertical game. The ball, and action, moves toward and away from the camera. There is no horizontal axis. It is extremely difficult to track the ball horizontally because of the speed, distance, and size of the ball. The axis is very flexible in golf, because no two courses are the same. There is a tee area that leads to a fairway that leads to a green, but no two are alike, and few have similar out-of-bounds situations.

Figure 12.6

Horizontal sports action.

The dramatic elements of golf occur on the greens during putting. The golf expression “you drive for show and putt for dough” means that the critical element of the game for the professional is putting. This is where scoring happens. Obviously, the objective of golf is to hit the ball fewer times than your opponents—the lowest score wins. The saving of strokes normally comes on the green during putting. The director must, therefore, concentrate on the putting portion of the game. It is at this point that the camera shots must warm. Here, too, the axis is a minor factor. But the director must make sure the audience is established so they can reference the location of the ball to the hole. Since putting is always in the direction of the hole, once establishment has taken place there is little need to re-establish. One caution, however: during the action portion of golf (striking the ball), it is essential that the audience be able to follow the bouncing ball. When the ball is putted, for example, the audience should be able to see the ball and the hole and be able to follow the ball as it rolls toward the hole. As the ball approaches the hole, the director may want to zoom in on the ball and the hole, but the reference between the two must always be maintained.

Figure 12.7

Vertical sports action.

Figure 12.8

Circular sports action.

Some track-and-field sports may be considered vertical as well: javelin, hammer, and shot put are examples.

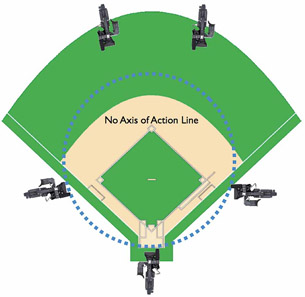

Circular Action

Some sports appear to be basically round-axis sports—baseball, boxing, racing, and wrestling are examples (see Figure 12.8). Golf putting may also fit into this general category. Here, the action seems to move in a circle (although most of the playing areas are square, such as baseball diamonds and boxing rings). Because of this, it is difficult to establish a specific axis. The director may help establishment through the use of boundaries, such as the foul lines in baseball or the ropes of the boxing ring. The audience generally will not mind a loss of orientation in these sports as long as re-establishment is provided periodically.

Combinations

Most sports are a combination of the general types we have just discussed. Football is a team, horizontal, and stop-and-go sport. Baseball is a team, stop-and-go, basically circular sport (although the action of the ball, from the pitcher’s delivery to the batter, as well as its flight from the bat, is more vertical than circular). Golf is an individual, vertical, stop-and-go sport.

Personalize the Production

I’m a firm believer that more cameras do not make a better director and do not make a better show. I’ve seen directors take four cameras and make them look like eight and vice versa. Whether the viewing public sees more because cameras are used depends on the ability of the director. My number one priority is the athlete. We try to personalize, thereby enabling the viewer to experience the emotion of the game. .. My camera (operators) know that when someone scores, I want to see his/her face as well as the faces of the opposing coaches. I’ve tried to instillin my people a principle I learned years ago. .. that the individual is the key to any story.

Chet Forte, Director

These classifications are important because they provide the basis for the design of coverage. The placement of cameras for proper coverage will depend on the axis of the game. The size of shots used, the lenses needed for those shots, and the need to establish and reestablish at specific times will be determined by these factors.

(Note: Additional camera placement diagrams can be found in Appendix II)

Coverage Design

Follow the Bouncing Ball: The single most critical production value in sports coverage is the need to know where the ball is at all times. This is true for all sports, with perhaps the exception of individual sports, such as boxing and wrestling, where there is no ball to maneuver.

Needs of the Audience

Sports coverage is presentational television. The directing style is normally invisible. The need of the audience to know the status of the contest is primary. The job of the director is to tell the story to the audience.

Orientation: The audience must have clearly in mind the general situation regarding the game. They must know which team/individual has control or has the momentum in the contest. This orientation is different from establishing, which deals with spatial location. Orientation has to do with the emotional status of the contest. It also has to do with the current score. The audience must know which team/individual has scored the most points (or fewest points as in golf). Your first question when arriving late to watch a football game with friends is usually “What’s the score?” It is part of orientation.

Orientation also includes time/distance/ frame factors. How much time is remaining in the game/quarter/period? How much more distance must the runner cover? What bowling frame (or boxing round) are we in? So, after you have asked what the score is, your next question may be “What quarter are they in, and how much time is left?” It is easy for the director to forget about the orientation needs of the audience. From a position in the remote truck, the director knows the orientation factors, but the audience at home does not. It is a general rule that the audience must be reoriented after each play in football (where yardage, down, and time are important) and after each hole in golf (who is leading, what hole we are on). These are just examples. It is not just the last two minutes of a football or basketball game in which the audience wants to know the time remaining; they want to know periodically throughout the game.

Direction of Play: The direction the ball and move to score must be established and maintained. The audience does not need to know if the stadium or playing floor runs north-south or east-west (although almost all outdoor football stadiums run north-south, with camera coverage coming from the west stands because of the afternoon sun). The audience is not concerned about the location of the stadium or arena in the city. They are concerned about the location of the ball and the direction of play within the boundaries, however.

Location of the Ball: The audience must know the location of the ball, especially in games such as football and hockey. The movement of the ball (puck) toward the goal is important. In football, the location of the ball with reference to yard markers must be established. The game changes drastically as the ball nears the defensive goal. The audience must re-establish location of the ball between plays, especially after plays that gain high yardage. For variety, a director may want to try some shots of the crowd as it follows a play, but unless the audience has been reestablished before the next play begins, they will be frustrated during the action.

Ball in the Frame: During action sequences, the audience must see the ball in the frame. This is basic to follow-the-bouncing-ball coverage, as has been noted. There is nothing more frustrating to the audience than not knowing where the ball is during action.

Directing Style

Directing style during action elements of a sporting event must be basically invisible. Directors must place themselves psychologically in the position of the audience and then show the audience what they need and want to see.

Directors, especially new directors, should plan to select an action camera that will handle the bulk of the coverage during the action portions of stop-and-go contests. This is especially true of games in which the ball moves quickly or where the action is complex. Other cameras can then be designated to provide coverage during non-action periods.

It is only during the time-out points in stop- and-go that the director may want to show a little creativity or pump up the coverage with production values, such as instant replay, tight shots, color analysis, or insertion of graphics for additional information. As a general rule, no more than 35 percent of the show should be taken up with color coverage, unless the contest is so poor it is necessary.

The director must have a sense of the pace of the sport and attempt to match that pace with the style of directing. In many ways, the movement of the game and the movement of the athletes in the game are much like directing a musical production, such as a dance or a concert. The movement of the game will rise and fall as the conflict heats and cools. The physical action of a football team must be as precise and rehearsed as that of a ballet group. The quality director will be able to sense this pace and movement and build on it by using a directing style that matches and augments the game.

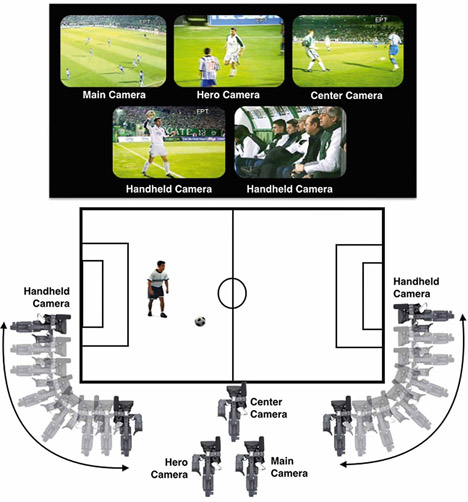

World Cup—Camera One Description

Camera one: Main camera positioned at midfield. Camera one is the main coverage camera or master shot. The shot is wide enough to show the flow of play, but not so wide that the ball and players become specks on the screen. The basic philosophy is to show everyone involved in the play, but not anyone who is clearly out of the flow. The camera leads the play in terms of direction of camera movement.

Broadcasters Handbook, XV FIFA World Cup

Ed Goren, Former Vice Chairman of Fox Sports Media Group, tells the story about a fight he was producing in San Juan, Puerto Rico, in 1976. It was between Muhammad Ali and Jean Pierre Coopman. Ali was clearly the favorite and the audience thought the fight would be quickly over. As Goren tells it, he believes that Ali kept the fight going just for television. “It’s fight night,” Goren recalls, “and I’m on the stairs of the television truck, and here comes Angelo Dundee [Ali’s trainer] and the Ali entourage. I yell out, ‘Hey, champ, how many rounds is this gonna go?’ And he goes, ‘How many do you need to get your commercials in?’ I go ‘Give me five.’ He nods. I think he knocked him out in the first 30 seconds of the sixth round.”

Adapted from P. J. Bednarski’s article in the Sports Video Group Newsletter

Facilities and Coverage

In most small and medium-sized markets, the director makes the decisions regarding camera shots, camera movement, the development of graphics, and the actions of talent. In sports coverage, the director becomes the center of a coordinated effort by all talent and crew to provide shots, tape replays, and other input from which the director can select what will be put out on the air. He or she becomes an editor, in this sense, selecting and guiding the production. That is not to say that the director does not call for specific shots, coverage, and isolation. But the tempo of the activity in the director’s truck is so rapid that the director cannot possibly talk through every shot or sequence with crew and talent.

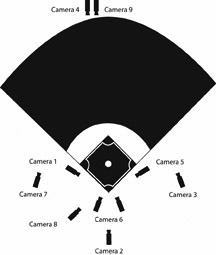

Assigning Cameras: Specific camera placement recommendations for various sports are included later in this chapter. At this point, we will outline the general types of camera coverage assignments that can be made for any situation. The camera designations outlined in this section deal with the type of coverage the camera generally provides. Depending on how many individual camera units you are blessed with for a particular production, each can be generally designated in one of these types. Our concern here is with assignments, not numbers (see Figure 12.19).

Each camera will have a general responsibility: (1) action/game; (2) hero/shag; or (3) ISO/special assignment.

Main/Action/Game Camera: The main camera, also often called an action or game camera, is responsible for covering the general action of the sport. This does not mean the director may not use other cameras for this purpose, but the action camera has that specific assignment. If, for example, a football team moves the ball to the one-yard line, you may want to increase warmth by using a utility camera behind the goal post to get a different view of the impending battle at the line. But for general assignment, the action camera has that specific responsibility.

Figure 12.9 Five camera placements for a soccer/football game.

Hero/Shag Camera: The hero, or shag, camera takes close-ups following a particularly outstanding athletic effort, thus the “hero” designation. This camera can also be used to follow the action to highlight important points in the context—hence the “shag” designation. (The term comes from the concept of shagging fly balls in the outfield during baseball practice. This camera is chasing down various shots like an outfielder shags fly balls.) The camera operator must be able to sense the drama and emotion of the contest and give the director shots that show that drama. For example, even though the basketball game continues following a driving lay-up by a guard on the team, the hero camera operator will give the director a shot of the guard. If the shot the guard attempts is blocked by the big center, the hero camera will focus on the center. The person who makes the play gets the camera shot.

On the other hand, if a football linebacker makes a particularly bruising tackle and injures the runner, the hero camera will focus on the injured player (as long as the injury is not terribly serious), while another camera takes shots of the linebacker. Similarly, the hero camera (with instruction from the director) may concentrate on the tennis player who seems to be losing the momentum in the match. If the player who seemed to have control of the match is beginning to slip, the hero camera will concentrate there. That is where the story is. If, on the other hand, the opponent is making a great comeback and is playing better tennis, that may be the story. The hero/shag camera also covers referees during penalty situations. That is part of the shag responsibility. It is the job of the hero or shag camera(s) to fill in the emotions of the game and to give the director shots that help the production do that.

ISO Cameras/Special-Assignment Cameras: ISO cameras cover specific (isolated) anticipated action points that can be tape-recorded for later playback. The ISO camera operator’s responsibility is to understand the sport well enough to determine when specific actions in the game can be expected. For example, third-and-long yardage situations in football generally mean the team will throw a pass. In addition, the ISO camera operator should know (from preproduction meetings) what style of game a particular team (or individual) normally plays. This information will give the ISO camera operator a chance to feed the tape assistant director or operator a shot that may be usable when play slows or stops.

The director may have time to cue the ISO cameras regarding particular anticipated actions, but then the ISO cameras are on their own to provide the shots. The director will not have time to talk them through such coverage.

Special-assignment cameras are designated for specific coverage during the game. Sideline cameras in football or basketball may have the assignment of providing coverage of the bench or the coach. They may shoot sideline talent for special reports. Other such cameras may cover talent in the booth or provide shots of a clock. Most coverage situations in smaller markets and non-network feeds do not have the luxury of many such units, and ISO cameras can fill both responsibilities.

Camera Initiative: In preproduction meetings, the specific assignments for each camera are reviewed. The camera operators must know what part of the coverage is their responsibility. Specific game situations should be reviewed—“what if” situations. “What do we do if the War Chiefs get inside the 10-yard line?” “Who gets shots of Coach Johnson?”

Before game time, the camera operators experiment with their cameras to see what kinds of shots they can get within their specific assignment, then they may experiment to see what other shots they can get to add to the repertoire of shots from which the director can select (see Figure 12.10).

During the game, all camera operators should provide the director with a broadcast stable shot almost all the time, and they should tell the director (via intercom) when they think they have got a shot the director can use for some effect—in a way, they try to sell the director on their shot or potential shot.

Sometimes the camera operator may take the initiative to begin to get a particular shot and the director accidentally cuts to that camera in the middle of the move to get to the shot. As a director works with a crew on coverage, however, each will get to know how the other works, so such glitches will occur rarely. The director should be able to watch the monitors of all cameras. Such a cut is the director’s mistake, not the camera operator’s (unless the director has called for a specific shot on that camera and the operator is out freelancing on his or her own).

When the action of the contest is taking place, the director may be locked to an action camera. The other camera operators, however, must have their heads into the game and should be looking for shots so that when the action stops or slows, they can help tell the story and support the style, mood, pace, and rate of the project (see Figure 12.11).

Figure 12.10

Before game time, camera operators should experiment to see what kinds of shots they can get within their specific assignment.

Directing Replays

A replay always breaks the viewers’ connection with the reality of the timeline of the event. Therefore there must be a strong motivation for a replay—only then does it enhance the coverage. Unnecessary replays annoy the viewer.

Kalevi Uusivuori and Tapani Parm, Producers, YLE, Finland

This same kind of teamwork occurs with replay operators and the replay assistant directors (see Figure 12.12). The director usually does not have time to call all the replay setups, or assign a particular camera to a particular recorder. Nor can he or she tell each ISO camera what part of the action to cover. The replay AD or the operator will select (using a simple routing switcher at the recorder) which camera to record on which ISO machine. When the director needs a replay, slo-mo, or ISO of any kind, the replay AD can tell the director what is available—on which recorder—and sell the director a particular cut. The director can then decide which replay to use. Normal coverage in a small market will have two or three replay machines capable of playback at regular and slow-motion speeds.

Camera Blocking Notes from Fox Sports Baseball

Camera 1: Low Third Base

- On left handed (LH) batters shoot waist-shots for stats, after tally goes out zoom back for head-to-toe shot

- If LH batter bunts, give batter more looking room on the left side of screen and go with ball

- Right handed (RH) pitchers

- Both dugouts

- If you have a batter and there are two men on base, take the backup runner after the ball is put into play

- If you do not have a batter, you have the lead runner

- If bases are loaded and you have the lead runner, you score lead runner and then pick up runner that was on first trying to advance

- Low cameras runner responsibilities will cascade as runners cross the plate

- If you do not have a batter or lead runner, shoot the pitcher. After pitcher goes into wind-up, go shag the entire field

- Cover plays at first base, after play bring player into third base dugout; if batter was on other team look for infield hero shot

- On-deck circles

- When following runners always shoot head-to-toe

Camera 2: High Home

- Follow the ball; play-by-play

- Cover appeals with first and third base umpires

- Infield and outfield defense: Put home plate in lower-right corner as a reference and then pan left to right—sweep bases same as defensive shot (if gap in Left Center or Right Center, include home-plate in corner of shot)

- Two-shot runners at first and second or second and third

- If you have a runner at second base, please include runner on your battery shot

- Always include the outfielders in the picture when the ball is hit to the outfield; show where the ball is going and who is going to catch it

- We will stay on camera 2 for all plays at home plate

Figure 12.11

Camera blocking notes from baseball.

Source: Courtesy of directors James Angio and Joseph Maar.

Camera 3: High First Base

- Shag infield and outfield

- Defensive pull across: get catch of ball through the throw to a base

- Go for infield or outfield hero shot after play

- If the drama is at first base where the out is made, keep a look-out for the first baseman, runner/umpire reaction

- Two-shot of runners at first and second

- Pick-offs at first base

- If runner steals go with runner

- If ball is overthrown at first or second base, go with ball

- Pitcher-runner shot at third base

- Triangle shot (pitcher/home plate/third base): show the whole thing when there is a chance of a squeeze bunt or sacrifice play at home

- If there are runners at the corner, you may be asked to cover the potential pick-off play at first base

- Dugout shots

- On-deck circles

- Third base coach for signs

- Players/managers in dugout

Camera 4: Center Field

- Pitcher-batter-umpire shot

- Go with ball on passed balls, wild pitches, pop-ups behind the plate and steals of second base

- Go with ball if it’s on the ground between second base and shortstop

- If ball is in the air, wait until your tally light goes out and then go for the shag/defense

- On a routine out or great play, stay with player for hero shot

- If ball is still in play, follow ball until play is dead

- Do not worry about pick-offs at first base

- Do worry about pick-offs at third base

- Base on balls: follow runner to first base, head-to-toe

- If pitcher strikes out batter to end the inning follow off pitcher

- If pitcher strikes out batter and it’s only out 1 or 2, follow batter to dugout

- Dugout reaction shots

- Follow on-deck batter to batters box

- On home runs, listen to the announcers; you have three options:

- Follow the batter after swing, push in tight for reaction

- Pause, then go for ball—looking for diving catch, player climbing the wall to steal a home run, etc.

- Zoom to pitcher for reaction shot as ball is being launched

Camera 5: Low First Base

- Right handed (RH) batters: waist-shot for stats; after tally goes out, zoom back for head-to-toe

- If RH batter bunts, give the batter more looking room on the right side of screen and go with ball

- LH pitchers

- If you have a batter and there are two men on base, take the backup runner after the ball is put into play

- If you do not have a batter you will have the lead runner

- If the bases are loaded and you have the lead runner, you score lead runner and then pick up runner that was on first trying to advance

- Low cameras runner responsibilities will cascade (or alternate) as runners cross the plate

- If you don’t have a batter or lead runner shoot the pitcher, after pitcher goes into his wind-up shag the entire field

- Cover plays at first base

- If it’s a routine out at first base, follow the player back to the dugout

- After play look for infield hero shot

- Both dugouts

- On-deck circles

- When following runners, always shoot head-to-toe

Camera 6: Low Home

- Tight shot of pitcher

- Pitcher-batter shot

- On LH batters you need to move to your left

- On RH batters you need to move to your right

- Follow ball when your tally light goes out

- Look out for behind-the-plate action

- Cover shots

- Runners with good speed: cover the runner at first base; if he steals go with runner

- If ball is hit up-the-middle and a runner crosses in your path, then pick up runner trying to score; what really looks good here is the third base coach trying to hold up runner or giving him the advance sign to home plate

Camera 7: High Third Base

- Pitchers

- Plays at first base

- Dugouts

- On-deck circles

- Pitcher-runner shot

- If runner steals go with runner

- Two-shots of runners at second and third

- Runners at first and third

- Help on passed ball and wild pitches

- If you have a runner, stay with him

- If no runner responsibilities: go with ball for defense shag CF to RF

- Beauty shots

- Congrats in dugout after scoring play

- Sometimes shoot LH batters to show his stance

- Players/managers in dugout

- If you’re on the pitcher-runner shot and the pitcher throws over first, don’t move; we can cover the man stealing and also see if there had been a balk by staying on your pitcher-runner shot

Camera 8: Concourse Level, Third Base Side—shooting down first base line

- Include batter, catcher, pitcher, first baseman

- Ball looks great hooking down the right field line

- Great diving play by first baseman

- Shag from CF to RF

- Bunts by both RH and LH batters

- If there’s a good runner at first base, include catcher and runner—this looks great for pick-offs at first base

- Suicide squeeze at home

- Dugouts

- On-deck circles

Camera 9: Center Field

Frequently, directors use a second camera as a tight ISO.

Directing Graphics

Primarily, sports coverage is a numbers game. There are scores, player numbers, and statistics to be organized and presented in a dynamic view on demand. Multichannel character generators and fast operators are a must. Success here often depends on careful pre-game or pre-game-date assembly and storage of names and player stats. Graphics and replay are the most heavily involved elements during the pre-game production where ten-things-at-once displays are made to happen with the push of a button during the game.

Bennett Liles, Production

In sport production, directors have the same type of relationship with graphics as they do with replay ADs and camera operators. A font coordinator coordinates the loading of graphic material into the graphics equipment coordinating the work of the graphics operator with the needs of the producer/director of the production. Pre-existing information is typed into the equipment before the game begins in addition to formatting pages used to input statistical material gathered during the course of the game. This “in game” information can be manually inputted during the game or it can be delivered automatically to the device during the competition by a sport data interface. Before the event begins, individual statistics that producers and/or directors anticipate using will be some statistical material during the contest (score, yardage, fouls, field goals, records) that will be entered for immediate display on the screen. Some sports productions (although it is a rarity) will use two character generators—one for retrieval of pre-produced graphics and one for graphics entered during the production.

Shading

It is essential to have all cameras properly adjusted for optimal image quality. Video operators (VO), sometimes known as shaders, are responsible for shading or adjusting the cameras. Cameras need constant attention, especially when shooting outdoors. As the weather changes or as the sun and/or clouds move across the sky, the lighting can change drastically on the same field of play. Video operators work in the video control area of the mobile unit, using the camera control unit (CCU) or remote control unit (RCU) to adjust the various components of the cameras. Generally, an RCU is used to control the CCU.

Video operators adjust cameras for correct color, white balance, and contrast. VOs use master black (pedestal) and the white level (iris) for camera adjustments. They use an oscilloscope and waveform monitor to enable them to create the best-quality video image.

The Crew

The producer and director are responsible for ensuring the needs of their crew are met. This care includes good lodging, good food, and protection from the elements. If the crew cannot leave during a production, catering will need to be provided. If the crew’s needs are neglected, attitudes can deteriorate. Low morale in the crew can impact the overall quality of the entire project.

Figure 12.12

Replay operators and the replay assistant directors have to work together as a team to be have the right replay ready for the director.

The crew must be prepared for any type of weather when shooting an outdoor remote. During warm weather, they should wear sun protection, light-colored clothes, and be prepared for sudden weather changes, such as rain or temperature drops. Cold weather shoots require layered clothing so that, as the temperature fluctuates, they can dress accordingly.

Replays

Replays are shown whenever the director considers a particular action noteworthy. As a general rule, replays do not cut into live action when the sport is in play. The director may overlap some important replays over live action but only if the live action does not involve interesting play. There must never be a danger of losing important action. The order and length of the replay is the director’s call.

Replays generally enter and leave by a digital effect so that the audience knows that it is a replay and not live action. Many times, replays end with a freeze frame.

The International Amateur Athletic Federation Television Guidelines state that cameras should also focus on what happens after the finish for some time, before going into slow-motion replays. Reaction of the competitors is more important than slow motion. Slow-motion shots should have an editorial basis and should not be an automatic decision. It is advisable to have a variety of options available by isolating several cameras in the stadium.