10 Managing your photos in Lightroom

How to use the metadata tools in Lightroom to manage your catalogs

Photograph: Ocean concrete works, Vancouver, Canada © 2018 Martin Evening

Sony A7rII | 50mm | ISO 200 | f/8 @ 1/200

Here is a quick test for you: Can you remember all the things you photographed last month? Were there any particular shots that stood out? Okay, so how about that same month five years ago? Many photographers think they can successfully rely on their memory when accessing pictures from their photo archives. The fact is, as we shoot more and more photographs, this kind of approach is doomed to failure, and as time goes by, it will only get worse.

Lightroom can help you organize and catalog your images from the very first moment you import them. It provides a flexible system of file management that can free you from the rigid process of having to organize your images within system folders.

On the face of it, image management might seem like a chore, but the time you invest now in rating your photos and adding custom metadata, such as keywords, can easily bring its own rewards and justify the time spent doing this. Adding custom metadata to your photos will add value. For working photographers, this can mean adding commercial value by making such photos more easily accessible to someone carrying out a keyword search. Even adding just a minimal amount of metadata to your personal photos can help prevent precious photographs of friends, family, and places visited from being lost among an ever-growing catalog of images.

Working with Metadata

In the early days of digital photography, many photographers relied solely on a folder-based organizational system. Even today I come across photographers who use named folders to manage their entire image library. With a folder-based organizational system, the degree to which you can successfully retrieve specific images depends on your ability to memorize the folder structure and know where everything is stored. Anyone who is responsible for maintaining a large image archive knows that this method of file management can soon become unwieldy. What is needed is a cataloging program that can help you keep track of everything. Therefore, the trend these days is to use file management by metadata, where you search for a file by searching its attributes rather than by trying to remember which folder you put the picture in.

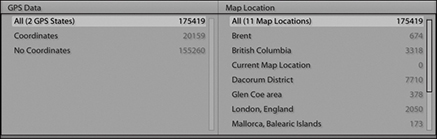

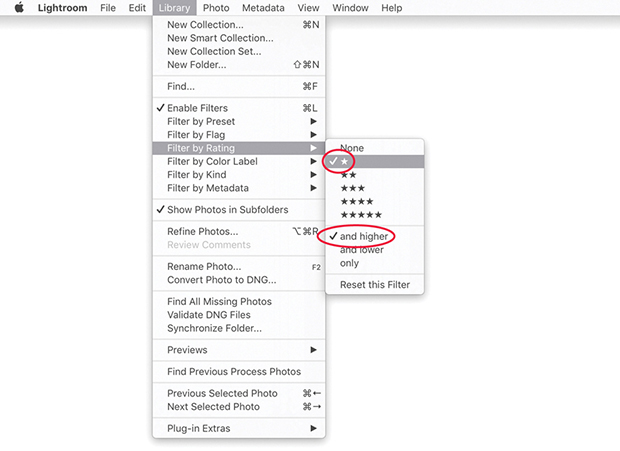

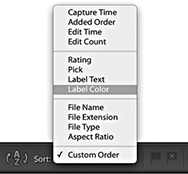

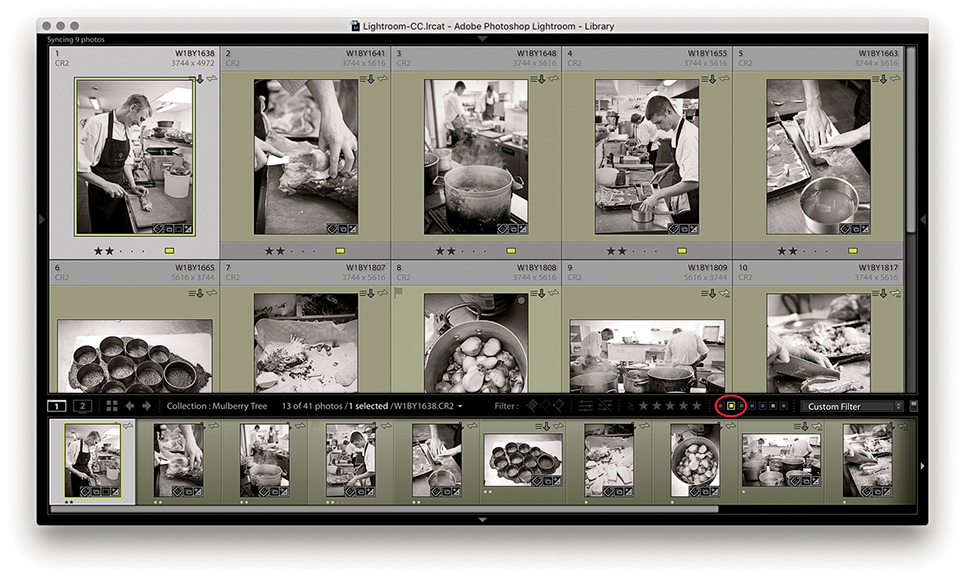

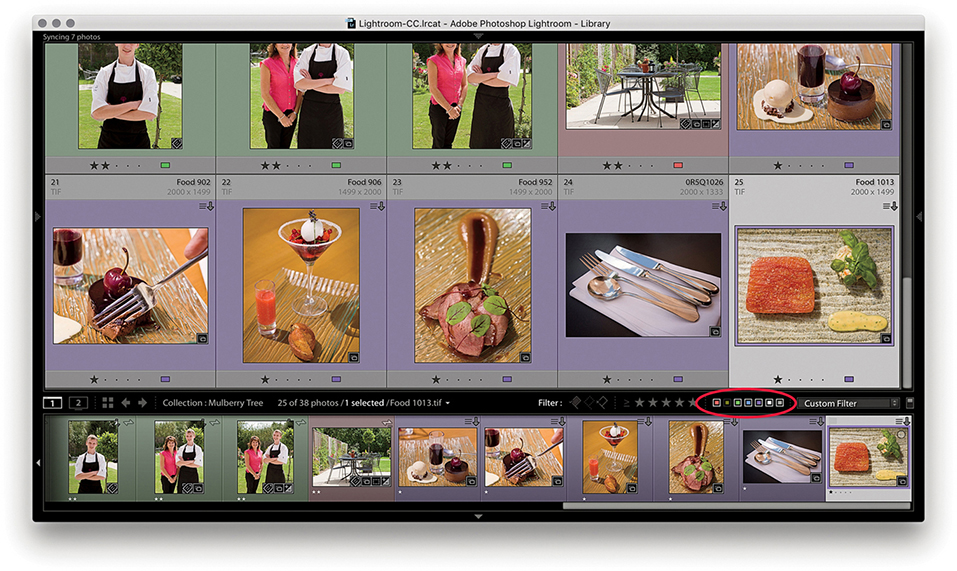

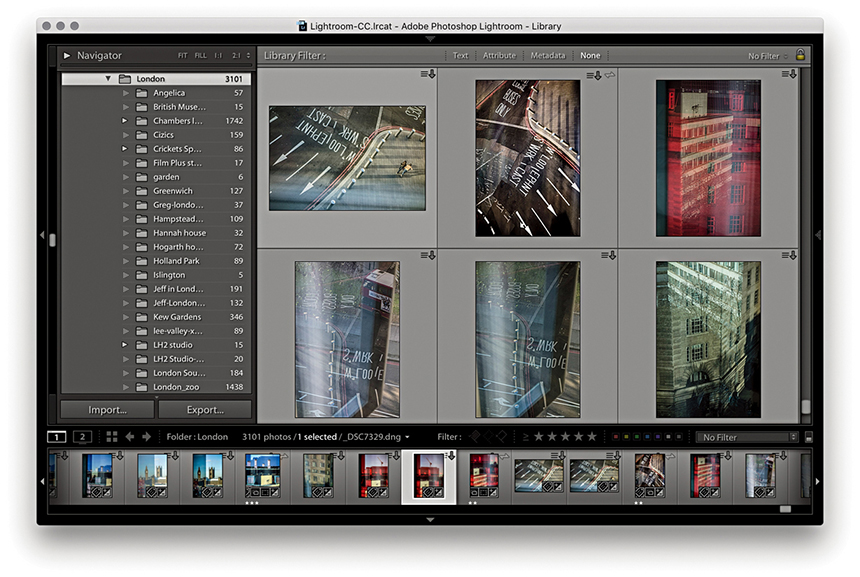

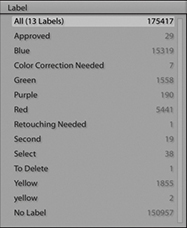

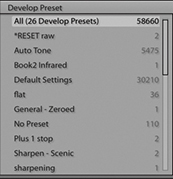

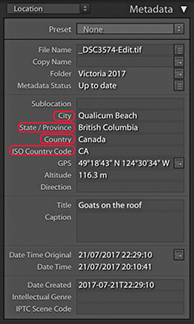

At the heart of any digital asset management (DAM) system is the ability to manage the files stored on that system through the use of metadata. A good DAM system should allow you to filter files using the metadata that is already embedded, as well as add custom metadata tags that can be used to carry out refined file searches and organize files into custom groupings. Some examples have already been shown in this book, such as how the Filmstrip filter can narrow down a selection of photos and display only those images with ratings of one star or higher, or two stars or higher, and so on. We have also looked at how to use the Folders panel to manage the image library. But the real power behind Lightroom is the database engine, which lets you carry out specific searches and quickly find the photos you are looking for. Figure 10.1 shows an example of metadata applied to a personal photograph, while Figure 10.2 shows an example of metadata applied to a commercial photograph.

It is in no way mandatory that you follow all the advice offered in this chapter, as everyone will have their own particular image-management requirements. You may find you just want to use the Folders panel to catalog your library images, and that is enough to satisfy your needs. But, hopefully, one of the key things you will learn in this chapter is that the time invested in cataloging an image collection can pay huge dividends in terms of the time saved when tracking down those pictures later. The image-management tools in Lightroom are far from being a complete asset-management solution, but they do offer something for nearly everyone. Some may find the cataloging tools in Lightroom insufficient. But even so, the data you input via Lightroom will be fully accessible in other image-asset-management programs. Once you start adding metadata to your images and grasp the benefits of doing so, you’ll soon reap the rewards.

The Different types of Metadata

Metadata is usually described as being data about data, which is used to help categorize information. Most of us carry out metadata searches on a daily basis. Every time you use an Internet search engine such as Google, you are using metadata to find what you are looking for. For example, if you type in a search for “elephants” and then click the Images filter, you can quickly locate lots of photographs of elephants (over 11 million of them). But if you were to refine the search criteria to “Indian elephants ceremonial,” you could start to narrow the search down further. If you need to find an email that was sent to you a year ago, you can use the search tools in your mail program to quickly find what you are looking for. iTunes is able to make use of embedded metadata to help you locate specific music, and a cable TV system will typically allow you to search for movies in a variety of ways. You can probably search for a specific film title by genre, release date, or director.

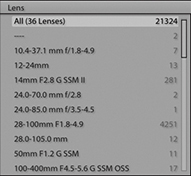

Lightroom also lets you organize your image files by metadata. All digital image files will contain a certain amount of camera data (known as EXIF metadata) to describe such things as the camera and lens used, along with other technical information, such as the lens settings and image file type. The thing is, the information that we would consider most important, such as who or what was in the picture when the photograph was shot, cannot be included automatically (although the Lightroom People feature can sometimes help). For the most part, photographers have to add such custom metadata information manually by entering keywords that describe the image. Keywords can be used to categorize the photos in your catalog, and if you are skilled at keywording, this can really help you manage your photos efficiently, as well as improve sales if you are in the business of supplying photos to an agency.

It is true that you will need to spend time entering all this metadata information, although there are various tips coming up in this chapter that will show you how to avoid repetitively entering this data for every single image. The trade-off is that the time invested in cataloging your images in the early stages can help reap rewards later in the time saved retrieving your files. In most cases, you need to configure essential metadata only once to create a custom metadata template. You can then apply this bulk metadata automatically to a set of imported photos. You can take the metadata cataloging further and add extensive custom metadata information to individual images. It all depends whether this is important for the type of work you do. Basically, the amount of effort spent adding metadata should always be proportional to how useful that information may be later. There is no point in going overboard doing this. How much time you should devote to this task and the amount of detailed information you record will all come down to how important that information will be to you personally and/or the people you are supplying your images to.

There is a lot of detailed content coming up in this chapter about how to apply, edit, and use metadata. Therefore, I thought the best way to introduce this subject would be to provide a quick example of how metadata can be used to carry out a search of the Lightroom catalog.

A Quick Image Search Using Metadata

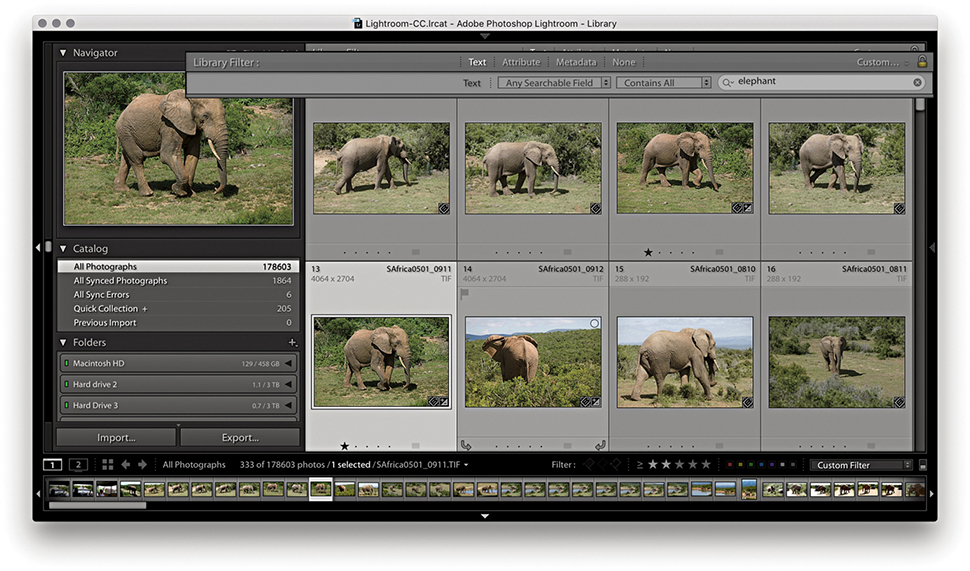

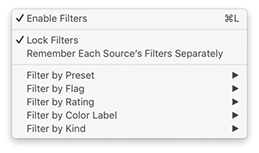

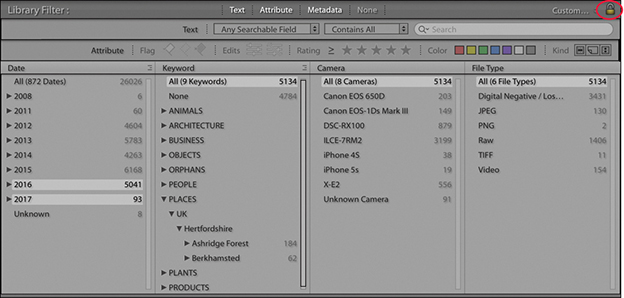

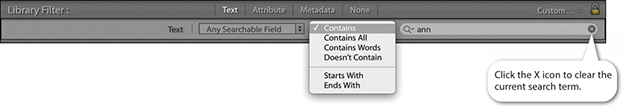

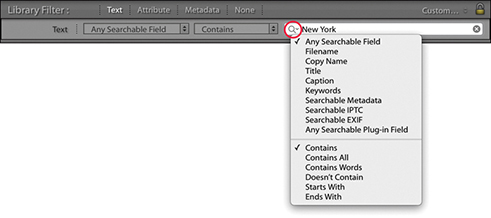

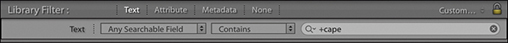

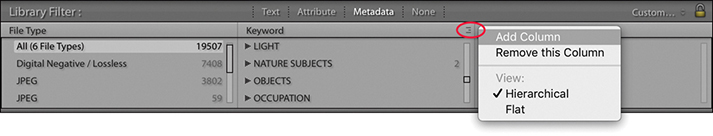

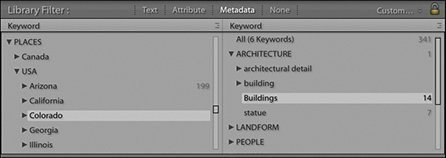

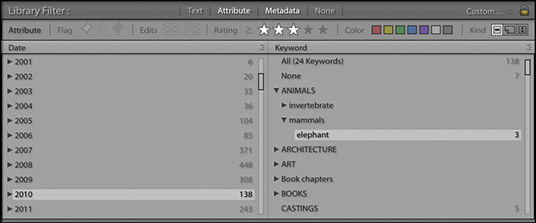

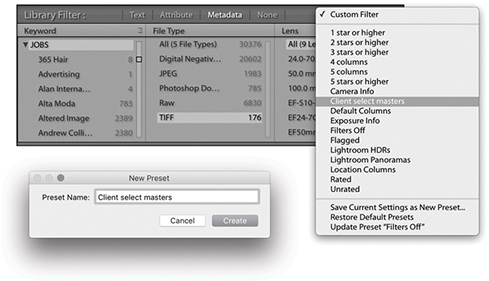

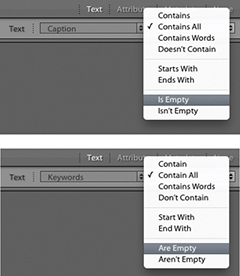

One of the key features in Library module is the Filter bar, which can be accessed at the top of the content area whenever you are in the Library Grid view mode. The Filter bar combines text search, file attribute, and metadata search functionality all in one. The following steps suggest just one of the ways you can use a metadata filter search to find photos quickly and thereby demonstrate the usefulness of tagging your photos with keywords.

1. Let me start by showing how you can search for photos quickly, without needing to refer to the folders the images are kept in. In the example, I selected all of the photos in the catalog and used ![]() (Mac) or

(Mac) or ![]() (PC) to reveal the Library Filter bar with the Text search field activated. Here, I typed “elephant” and I allowed the search to search within Any Searchable Field using Contains All search criteria. This filtered the catalog view to reveal 271 images with a text match for “elephant.” This could be wherever there was a match in a keyword, caption, or filename. A filtered selection of 271 images was obviously a lot easier to sort through than a search of the entire catalog, but there are ways you can use Lightroom to further narrow down a search.

(PC) to reveal the Library Filter bar with the Text search field activated. Here, I typed “elephant” and I allowed the search to search within Any Searchable Field using Contains All search criteria. This filtered the catalog view to reveal 271 images with a text match for “elephant.” This could be wherever there was a match in a keyword, caption, or filename. A filtered selection of 271 images was obviously a lot easier to sort through than a search of the entire catalog, but there are ways you can use Lightroom to further narrow down a search.

2. I then clicked the Attribute tab in the Filter bar and clicked the one-star button to narrow the search to elephant images with a rating of one star or higher. This reduced the selection to a more manageable 59 images.

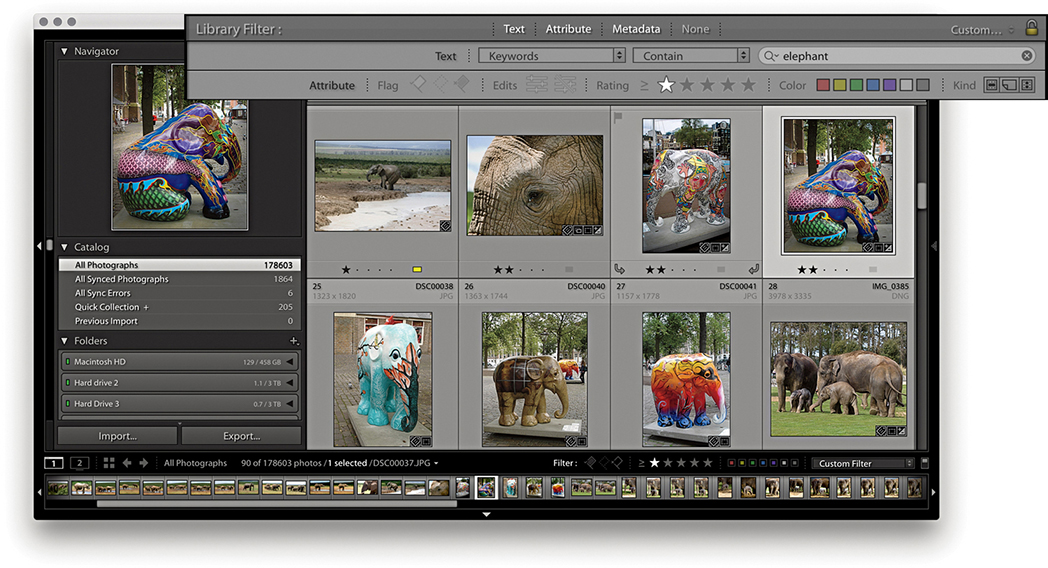

3. Lastly, I clicked the Metadata tab in the Filter bar and, in the Date column, clicked to select just those images that were shot in 2010. I also clicked the three-star button to display just those images with a rating of three stars or higher.

Metadata Panel

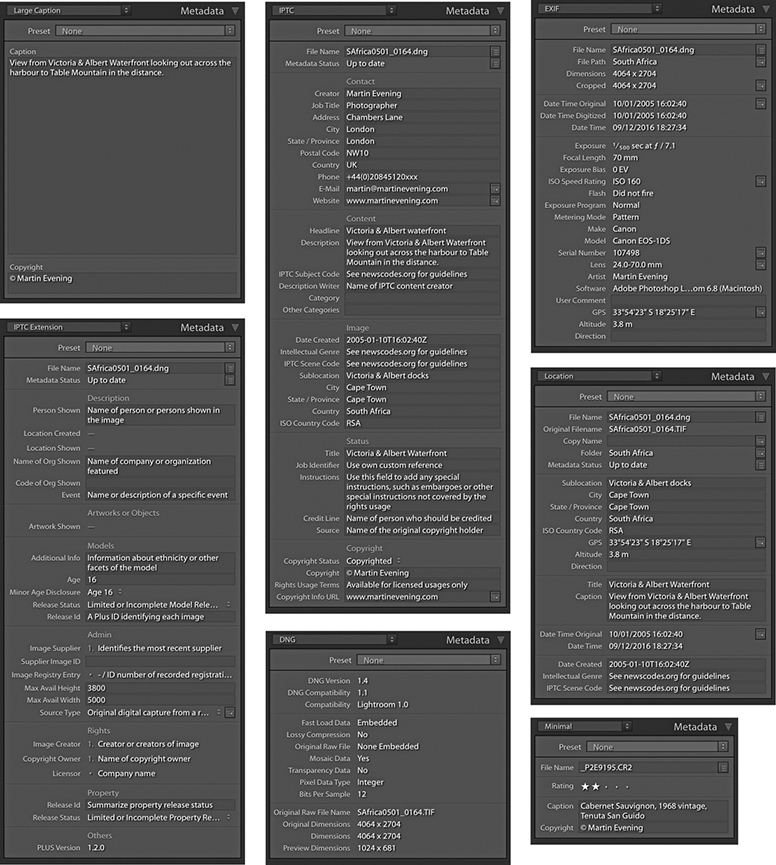

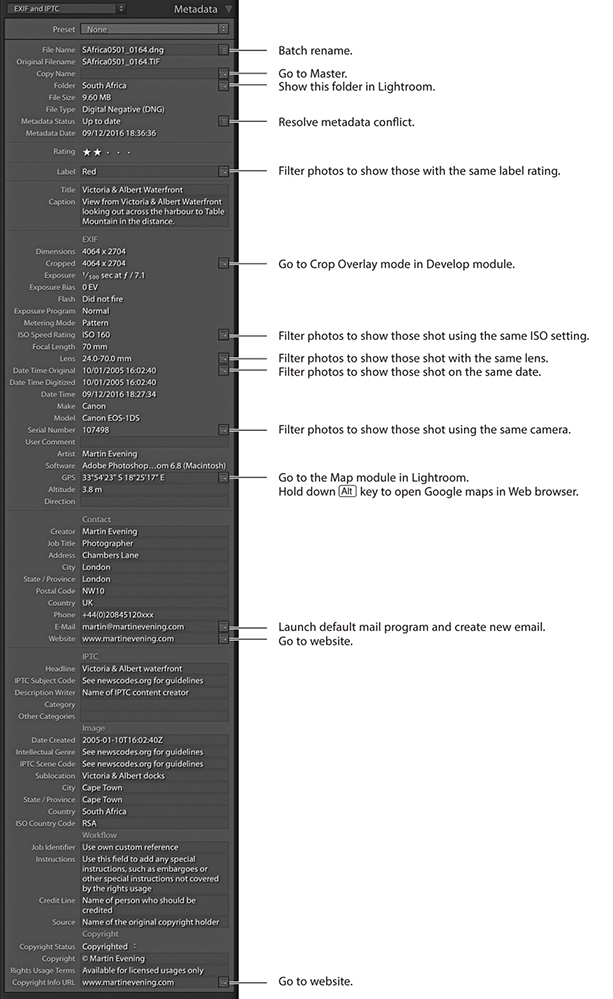

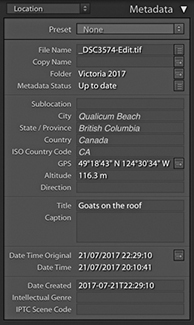

Let’s now look at the Metadata panel. Figure 10.3 shows the default Metadata panel view, which displays a condensed list of the file and camera information. At the top is the Preset menu with the same options as those found in the Import dialog Apply During Import panel (see also page 570 for more about creating and applying metadata presets). Below this are fields that show basic information about the file such as the File Name and Folder. Underneath that are the Title, Caption (elsewhere also referred to as “Description”), Copyright, Creator, and Location fields. These fields are all editable, and when you click a blank field, you can enter custom metadata, such as the image title and copyright information. Below this are Rating and Label, followed by the basic EXIF metadata items. This data is informational only and shows things like the file-size dimensions, camera used to take the photograph, camera settings, lens, and so forth. Some of the items in the Metadata panel have action arrows or other buttons to the right of the metadata item. These provide additional functions. For example, clicking the action arrow button next to Folder (circled in Figure 10.3) takes you directly to a Grid view of the source folder contents.

Metadata Panel View Modes

If the Metadata panel in your version of Lightroom looks different from the one shown in Figure 10.3, this is probably because you are using one of the 11 other Metadata panel layout views. If you click the View menu shown in Figure 10.4, you can access any of the alternative Metadata panel view options. In Figure 10.5, you can see a comparison of some of the main Metadata panel view modes. Each photo can contain a huge amount of metadata information, so if you want to see everything, you can select the EXIF and IPTC view. But if you want to work with a more manageable Metadata panel view, I suggest you select a Metadata panel view more suited to the task at hand. For example, the EXIF view mode displays all the non-editable EXIF metadata, whereas the IPTC view mode concentrates on displaying the IPTC custom metadata fields only. The IPTC Extension view can be selected to display additional IPTC Extension data. The Large Caption view mode displays a nice, large Caption metadata field, which gives you lots of room in which to write a text caption (the large caption space here does at least make the Caption field easy to target—click anywhere in the Caption field and you can start typing). While you are in data entry mode, pressing ![]() allows you to add a return character in this field section instead of committing the text.

allows you to add a return character in this field section instead of committing the text.

The Location panel mode provides a metadata view that is more useful for reviewing travel photographs. The Minimal and Quick Describe view modes are suited for compact Metadata panel viewing, such as when working on a small screen or laptop. And the DNG mode reveals specifics about the DNG data for selected DNG images. This lets you see specific DNG file information, such as whether lossy compression has been applied.

General and EXIF Metadata Items

Let’s now look in more detail at the items that can be displayed in the Metadata panel. Figure 10.6 shows a fairly complete list of the items you might see listed when using the EXIF and IPTC view mode. Many metadata items can be displayed here and most are self-explanatory. As you roll over the items listed in the Metadata panel, the tooltips provide extended explanations of how to use each of the fields. You might not see everything listed here in your version of Lightroom; certain items require the metadata to be present before they can be displayed. For example, only if there is an audio sidecar present will it appear as a metadata item just below Metadata Status. If you click the action button next to this, you’ll be able to listen to the audio annotation. If no audio sidecar file is attached, you won’t see anything listed.

Tip

Making audio notes via the camera is useful should you wish to record information, such as the name of a person you have just photographed or other information that you might want to write up later as a caption.

File Name

This displays the filename for the currently selected photo. If you need to change the name of a file, click inside this field to make any name changes. If you want to carry out a batch-rename action, select the photos you want to rename and click the button to the right to open the Rename Photos dialog.

Sidecar Files

The Sidecar Files item shows up whenever a sidecar file is found associated with an image. Sidecar files are always hidden from view in Lightroom, so this extra item in the Metadata panel lets you know whether an XMP sidecar is present.

Copy Name

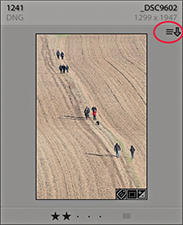

The Copy Name field refers to virtual copy images made in Lightroom. Each virtual copy image can provide an alternative version of the original master (or negative as it is sometimes described in Lightroom). By making virtual copies, you can apply different crops or color treatments. But because virtual copies all refer to the same master, they all share the same root filename. Whenever you create a new virtual copy, Lightroom labels each one as Copy 1, Copy 2, etc., but you may want to edit this name. In Figure 10.7, I renamed the virtual copy name Black and white. Virtual copy images can quite often end up being separated from the master, because you may have assigned a different star rating to the virtual copy version, they may be grouped in a collection, or they may have been removed from the master parent image. If you click the action button next to the copy name field (circled in Figure 10.7), you can quickly trace the master version of any virtual copy.

In Figure 10.8, you can see Grid view showing a master DNG image with two virtual copies to the right (see the page curl-icons circled in the bottom-left corners). The one on the right was renamed Black and white.

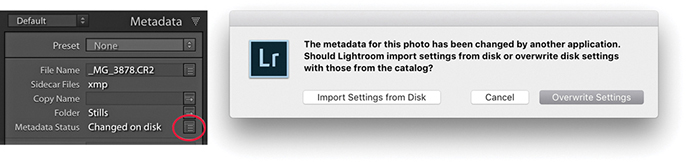

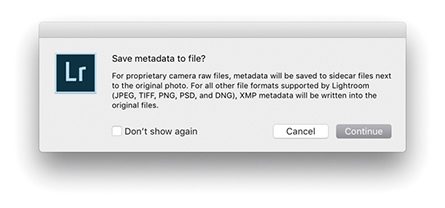

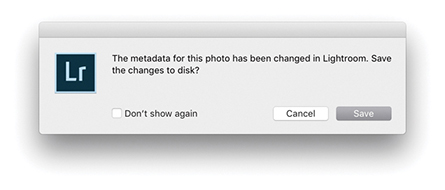

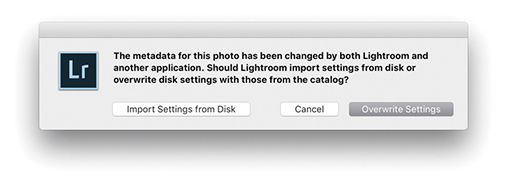

Metadata Status

If there is no metadata status conflict, the Metadata Status field will say “Up to date.” If the metadata for the photo has been altered since it was last saved to the file’s XMP space, it will say “Has been changed.” Clicking the action button opens a dialog prompting you to save the changes to disk. If the metadata has been edited externally in Bridge, but the settings have not yet been read in Lightroom, it will say “Changed on disk,” while a “Conflict detected” message indicates the metadata has been changed both in Bridge and Lightroom. In both cases, clicking the action button opens the metadata status dialog shown in Figure 10.9, where you can choose Import Settings from Disk, Overwrite Settings, or Cancel. The ins and outs of metadata saving, XMP spaces, and Lightroom settings are quite a complex subject. For a more detailed explanation, see pages 628 to 634.

Cropped photos

If a photo has been cropped, the Cropped measurement will appear in the Metadata panel, showing the crop dimensions in pixels. If you click the action arrow next to it, this takes you directly to the Crop Overlay mode in the Develop module.

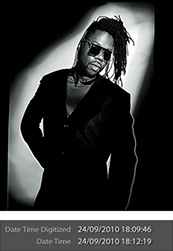

Date representation

Date Time Original and Date Time Digitized mean the date that a photo was captured or was first created, whereas the Date Time field indicates the time the file was last modified (such as a DNG conversion). Figures 10.10 through 10.12 explain the differences between these bits of metadata information.

Next to Date Time Original is the Go to Date action button (this applies only to digital capture images). Clicking this button filters the catalog view to show only those photos that have matching capture dates. To exit this filter view, use the ![]() (Mac) or

(Mac) or ![]() (PC) shortcut, which toggles the catalog filters on or off.

(PC) shortcut, which toggles the catalog filters on or off.

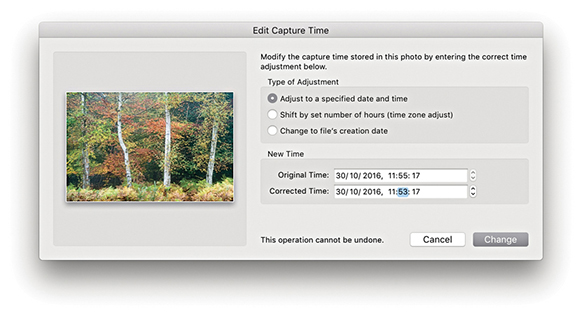

Capture time editing

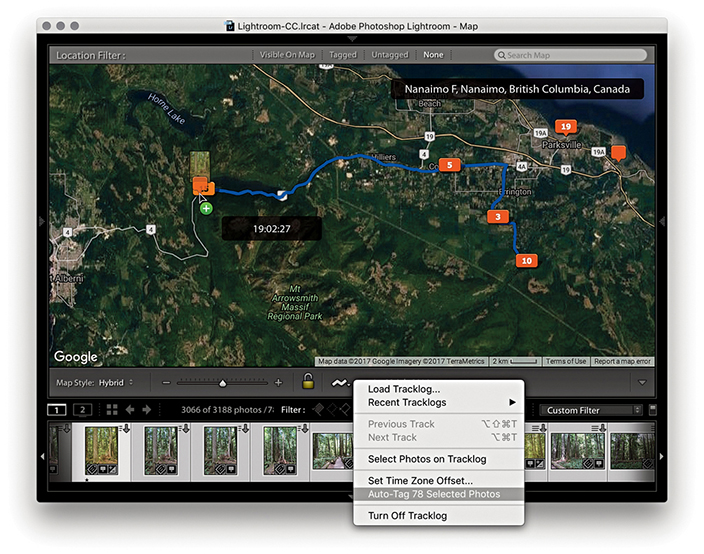

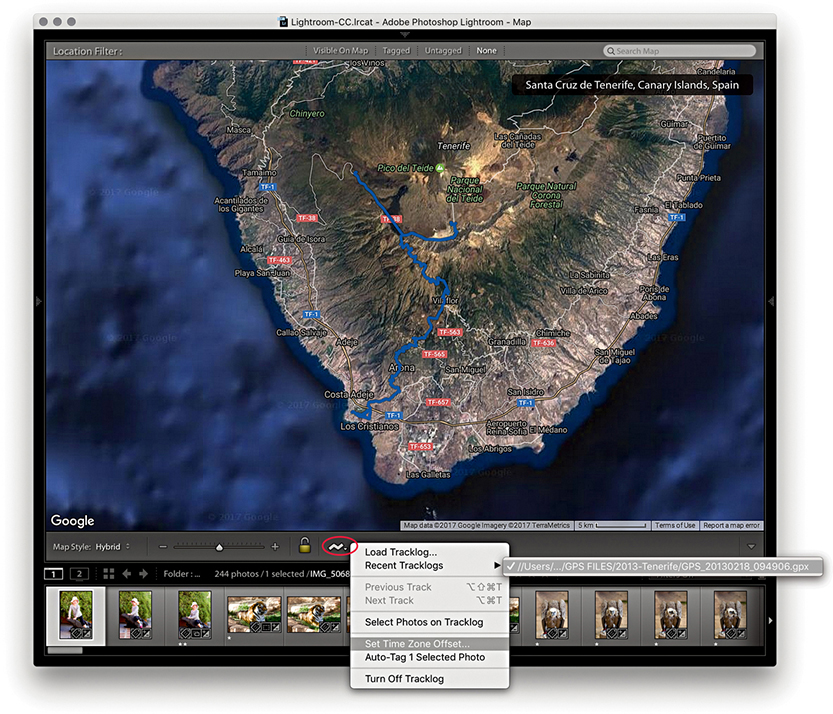

Maintaining a capture time record of the photos you shoot should be more than just a matter of idle curiosity. A lot can depend on having your photos accurately time-stamped. For example, when importing photos from more than one camera, it is important that the internal clocks of both cameras are in sync. Doing so means the photos will be correctly ordered when sorted by the capture time. Perhaps the internal clock in your camera is wrong. Did you remember to set the internal clock correctly when you first bought your camera? For critical, time-sensitive work such as GPS tagging via a separate GPS device, you may want to keep a regular check on your camera’s internal clock to ensure it is accurate.

If you know that the camera time and date settings are incorrect, you can address this by choosing Metadata ![]() Edit Capture Time while working in the Library module. The Edit Capture Time dialog (Figure 10.13) lets you amend the Date Time Original setting for an individual image or a group of images.

Edit Capture Time while working in the Library module. The Edit Capture Time dialog (Figure 10.13) lets you amend the Date Time Original setting for an individual image or a group of images.

If you find out too late that the date and time are wrong, the Edit Capture Time feature can help you restore the correct time to your captures. If you are editing the capture time for a selection of images, the “Adjust to a specified date and time” option lets you set the date for the current most selected image (the one shown in the dialog preview) and the remaining selected images will all reset their dates and time relative to this image. If the internal camera clock is correct but you simply forgot to adjust the camera clock to a new time zone, you might want to select the “Shift by set number of hours (time zone adjust)” option and adjust for any time-zone difference. At the bottom of the dialog, there is a warning that “This operation cannot be undone.” However, if you later go to the Metadata menu in Lightroom, you can choose Revert Capture Time to Original. This allows you to reset the capture time metadata. Also, the “Change to file creation date for each image” option allows you to change the capture time for the capture time setting in the camera EXIF data back to the original creation date.

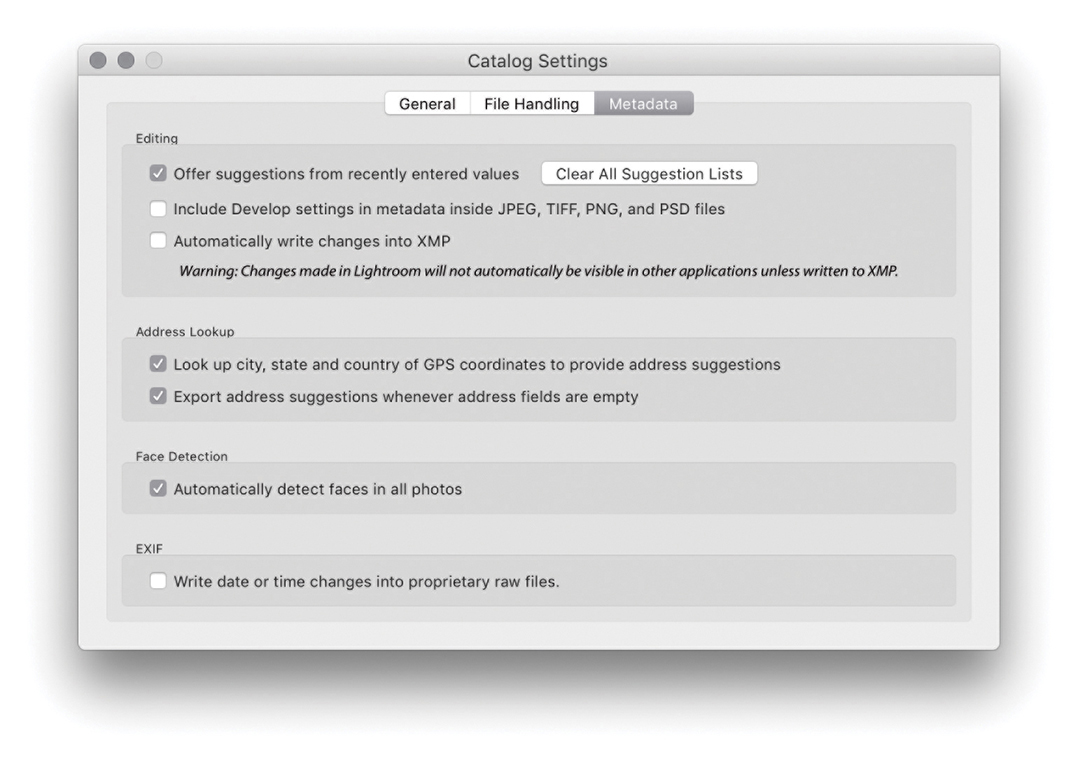

When you use the Edit Capture Time dialog to edit the original capture time settings for raw files, the changes made are applied to the XMP data only. If you go to the Metadata tab in the Lightroom Catalog Settings and go to the EXIF section at the bottom, you will see the option “Write data or time changes into proprietary raw files.” When this is checked, it lets you hardwire date changes into the EXIF field contained in the proprietary raw file (as opposed to simply writing to the XMP space). It is not normal practice to risk editing the internal metadata fields of undocumented proprietary raw files, so use with caution. The reason for having this preference is that when some workflows rely on external programs, it may be necessary to edit the EXIF field inside the actual raw file (for example, you may need to externally synchronize the raw files with a GPS log).

Tip

On the Mac, there is an application called A Better Finder Attributes to reset the Date Original and Date Time Digitized back to their actual times: publicspace.net/ABetterFinderAttributes. It works for a number of camera raw formats.

Camera model and serial number

These items instantly tell you which camera model and specific serial number were used to take a particular photograph. If you shoot using more than one digital camera body or have photos in the catalog taken by other photographers using the same camera type, this data can prove really useful, especially if you want to track down exactly which camera was used. Let’s say there is a problem with one of the cameras—there may be damage to the sensor or a camera focusing problem. Using this data, you can pinpoint which specific body is responsible.

Artist EXIF metadata

The Artist EXIF metadata will show up only if you have applied this as a custom user setting for your camera. This can be done quite easily on most cameras by searching for the Copyright menu item, where you can enter your personal copyright details (Figure 10.14). If there isn’t a Copyright menu item, you may find your camera comes with utility software. Connect it to the computer using a tethered connection and navigate to the section that allows you to enter and edit the Artist copyright field.

Embedding your name as the owner in the camera settings seems like a pretty good idea. This ensures the copyright name is always embedded in the capture file EXIF data. Just remember that if you borrow someone else’s camera or rent one, always check what the owner name metadata says. Once the owner metadata is embedded in the raw capture files, you will not be able to edit the EXIF data that easily. If you are feeling brave, it can be changed using an EXIF editor, such as ExifTool by Phil Harvey (sno.phy.queensu.ca/~phil/exiftool), but this is a command line-based editor and not particularly easy to use. While you can’t edit the Artist EXIF field directly, you can use Lightroom to edit the IPTC Creator field, which will work superficially because the two fields are linked in Lightroom.

Custom Information Metadata

So far, I have mostly described the fixed, embedded camera metadata that is displayed in the Metadata panel. We are now going to look at working with custom metadata, which is data that you can use to add image-specific information. This can broadly break down into information about the image, such as the caption, headline, and location details of where the picture was shot. You can also add custom metadata that includes contact information about who created the photograph, such as your name, address, phone number, email, and website. This information can also include how the photo might be classified and what copyright licensing restrictions might be in force. As you start applying metadata to individual photos or groups of images, you gain the ability to differentiate them further and can reap the benefits of having a carefully catalogued image database. Applying such metadata now will help you in the future. Not only can it allow people to contact you more easily, but it can also help when you are working in Lightroom and need to make a targeted image search.

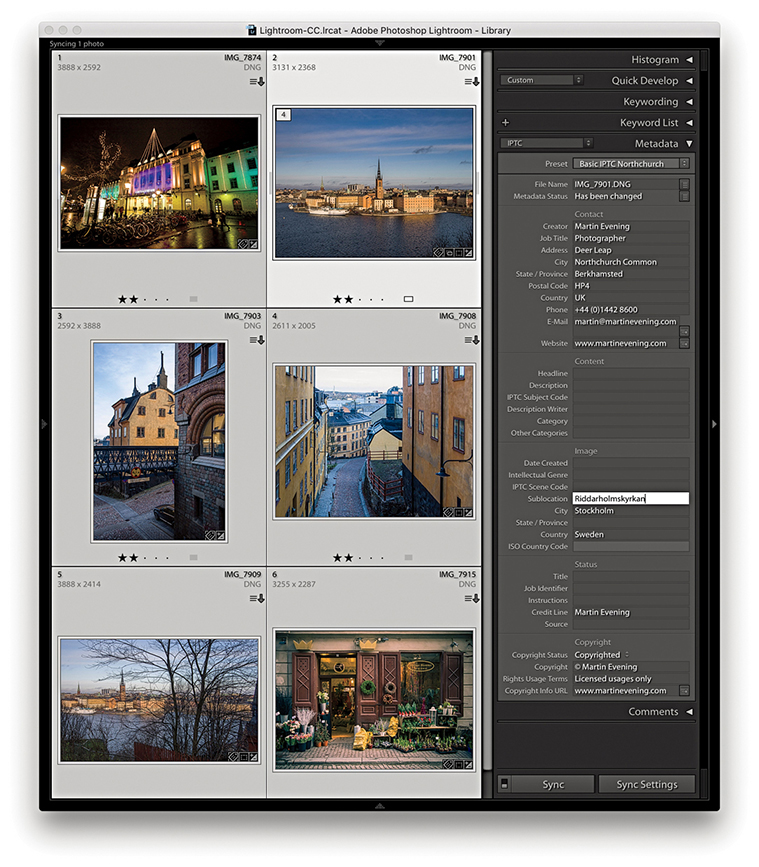

Figure 10.15 shows the Metadata panel in the IPTC view mode. You can see here that I have filled in the editable sections with examples of how you might use this panel to add descriptive information to a photo. You could, for example, select all the photos in a particular folder from the same shoot and add custom information to categorize them. Most of the items in this panel, such as Creator, Job Title, and Address, are self-explanatory, and this is data you would probably want to apply to nearly every photo. However, the Headline and Caption fields can be used to add image-specific information. The Headline field might be used to describe a photo shoot, such as Xmas catalog shoot 2018, or White-on-white fashion shoot, while the Caption field can be used to provide a brief description of a scene, such as Crowds line the streets at local festival to celebrate the Chinese New Year. These custom bits of information are essential when submitting images to a picture library, and they are particularly useful when you take into account that the value of an individual image is increased as more information is added. Even with a small-scale setup, you’ll find it rewarding to methodically catalog your photographs with basic metadata information in the Contact and other IPTC sections.

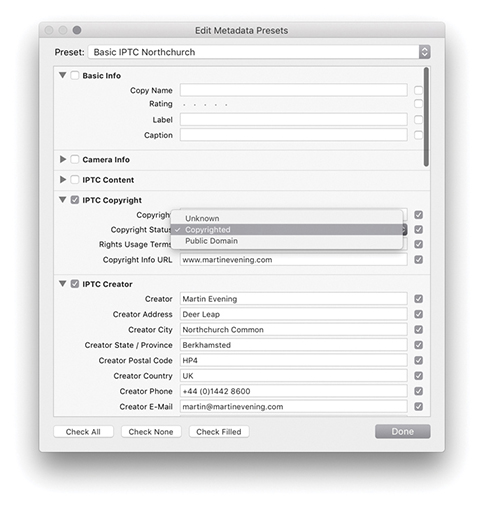

Metadata presets

You certainly do not want to spend too much time entering repetitive metadata. This is where the metadata presets (also known as metadata templates) come in handy, because you can use them to apply the metadata information that needs to be input on a regular basis. To create a new metadata preset, click the Preset menu shown in Figure 10.16 and select Edit Presets. This opens the Edit Metadata Presets dialog (Figure 10.17). The fields here will be populated with the IPTC metadata already applied to the currently selected photo, which you can use as the basis for a new preset. You can then edit the fields in this dialog as well as check the individual boxes for the items you wish to include. Having done that, click the Done button at the bottom to open the Save Changes dialog, where you can select Save As to save these settings as a new metadata preset.

Metadata presets provide a useful way to batch-apply informational metadata either at the import stage or later via the Metadata panel. You might therefore find it useful to create several metadata templates for the different types of shoots you normally do. Let’s say you are a sports photographer and are often required to photograph the home football team whenever the team plays a game at the local stadium. You could save yourself a lot of time by creating a template with the name of the football team and the location information and apply this template every time you photograph a home game. Even though the Lightroom Metadata panel cannot display all the items that can be included in a Metadata preset, other programs may be able to do so.

Tip

If nothing else, make sure that every photo you create contains your contact details, is marked as copyrighted, and has a copyright notice. Photographers should always take steps to ensure that any photographs they release into the public domain do not become classified as orphan works.

If a photograph has no identification as to who shot it and it is “found” by someone on the Internet, that photo becomes classified as an orphan work. Currently, this does not give anyone the legal right to use such images. However, in some countries, there have been recent attempts to change the law so that orphan works can be legitimately used without needing to trace the owner.

The message here is to make sure everything you create is marked with your copyright and beware of uploading photos to sites that may strip the copyright metadata from your images.

Editing and deleting metadata presets

If you want to edit an existing preset, first choose the preset you want to edit and then select Edit Presets. Apply the edit changes you want to make, and click the Done button. This opens the Save Changes dialog, where you will have to select Save As and choose a new name for the preset (it must be a new name—you cannot overwrite an existing preset). To remove a metadata preset, choose Edit Presets and select Delete Preset.

IPTC metadata

The items listed in the Edit Metadata Presets dialog are not as comprehensive as those found in Photoshop, Bridge, or other programs, but the editable items you see listed in Figure 10.17 do conform with the latest International Press Telecommunications Council (IPTC) standard file information specifications, as used worldwide by the stock library and publishing industries. Therefore, the metadata information you input via Lightroom will be recognizable when you export a file for use in any of these other programs. Conversely, Lightroom is able to display only the metadata information it knows about. It will not be able to display all the data that might have been embedded via Bridge or Capture One. Should this be a cause for concern? For those who regard this as a shortcoming in Lightroom, it may well prove to be a deal breaker. But for others, the metadata options that are available should be ample. Figure 10.17 provides a useful overview and suggestions on how to complete the Basic and IPTC fields, and Figure 10.18 shows a practical example of a metadata preset that would be suitable for everyday use. For help in understanding how to complete some of the advanced IPTC fields (such as the IPTC Subject Codes), I suggest you try visiting newscodes.org.

It is not mandatory all the listed fields be completed; just fill in as many as you find useful. For example, the IPTC Content section can be used to enter headline information and details of who wrote the description. The Description Writer field refers to the person who entered the metadata information: This might be a picture library editor, a photographer’s assistant, or a work colleague. This type of information is not something that you would necessarily want to add as part of a metadata preset. However, the IPTC Copyright section can list information about who owns the copyright plus Rights Usage Terms. The IPTC Creator section can also contain contact details such as your address, telephone, email, and website. This information will most likely remain the same until you move or change email accounts. The IPTC Image section allows you to enter information that is more specific to the image, such as the intellectual genre. The remaining fields can be used to describe when and where the photograph was shot, job reference (such as a client art order), and so on.

Once you are done, you can save this template as a new metadata preset and apply it whenever you import new images into the catalog. Essentially, metadata presets are available and editable via the Import Photos dialog. You therefore have the choice of applying metadata presets either at the import stage or via the Metadata panel Preset menu. This way, you can ensure that after each new import, all newly added photos carry complete copyright and contact information (Figure 10.19).

In Figure 10.18, you will notice I did not enter data into all the fields, and for those that were empty, I deliberately left the check boxes deselected. This is because a selected check box is saying “Change me.” When you create a metadata preset, you will often want to devise a preset that is general enough to cover certain types of shoots but without including terms that will make a preset too specific. Also, if you create a metadata preset that is designed to add metadata to specific IPTC fields, you may not want to overwrite any of the other fields that contain important metadata.

When a field in the Edit Metadata Presets dialog is checked but left blank, its description will turn red. The placeholder text in the field will say “Type to add, leave blank to clear,” reminding you that if you select the box and do not add any text, it will act as an eraser, deleting any data for that field. Let’s say I had an image where the Caption, Color Label, and Rating information had already been added. If I applied the metadata preset shown in Figure 10.18 but with all the boxes checked, it would overwrite these existing metadata settings with null content, thereby erasing the Caption, Color Label, and Rating data. So, when you create a new preset, it is always worth confirming that you select only those items that you intend to change; otherwise, your metadata presets can soon start messing up the photos in the catalog rather than enhancing them. Of course, you can always edit an existing preset and deliberately set the preset to erase older metadata if you think that would be useful. Configure these presets carefully, and always test them to make sure they behave exactly as you expect them to.

IPTC Extension metadata

Lightroom incorporates the IPTC Extension schema for XMP, which is a supplemental schema to the IPTC Core. It provides additional fields with which to input metadata that can be useful to a commercial photography business. If you refer back to the example shown in Figure 10.17 on page 571, you will see brief explanations of how these fields may be utilized. Basically, the IPTC Extension schema can provide additional information about the content of the image, such as the name, organization, or event featured in a photograph. It provides you with further fields to improve administration, whereby you can apply a globally unique identifier (GUID). It offers fields for precisely defining the licensing and copyrights of a particular photograph. For example, instead of just saying “This photo is copyrighted by so and so,” it allows you to specify the name of the copyright holder, as well as whom to contact to obtain a license. This might well be a picture library or a photo agent rather than the photographer. The image supplier can also be identified separately. Again, it might be a photo library that supplies the image rather than the photographer directly. For more information, visit the PLUS website: useplus.com.

If you photograph people, you can record specific model information such as the age of the model, which might be particularly relevant if the subject was a minor when the photo was shot. You can also provide a summary of the current model release status. The same thing applies to photographs of private properties where, under some circumstances, a property release may be required.

A more efficient way to add metadata

One of the things that continues to irk me about Bridge is that if you select a photo, make the Description field active in the Metadata panel, and enter new text, you have to press ![]() to commit, select the next image, and then retarget the Description field all over again to add a new description for the next photo.

to commit, select the next image, and then retarget the Description field all over again to add a new description for the next photo.

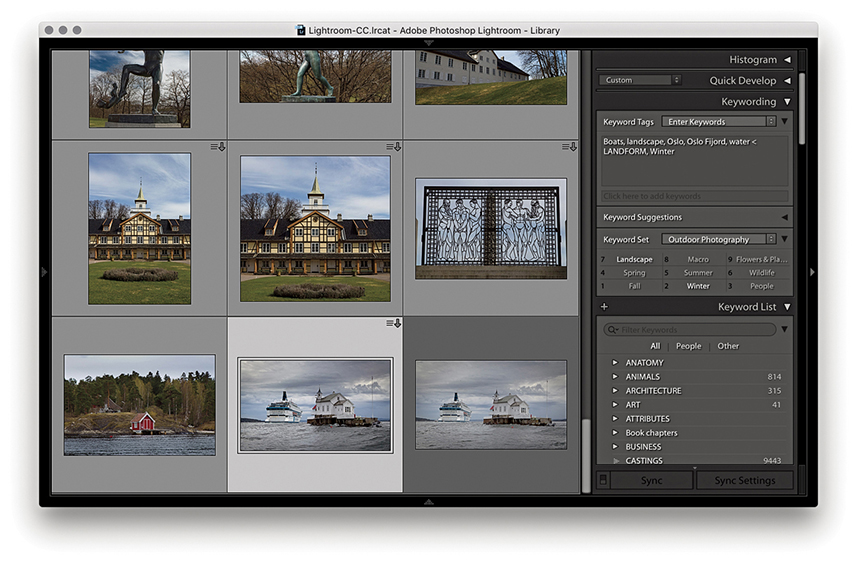

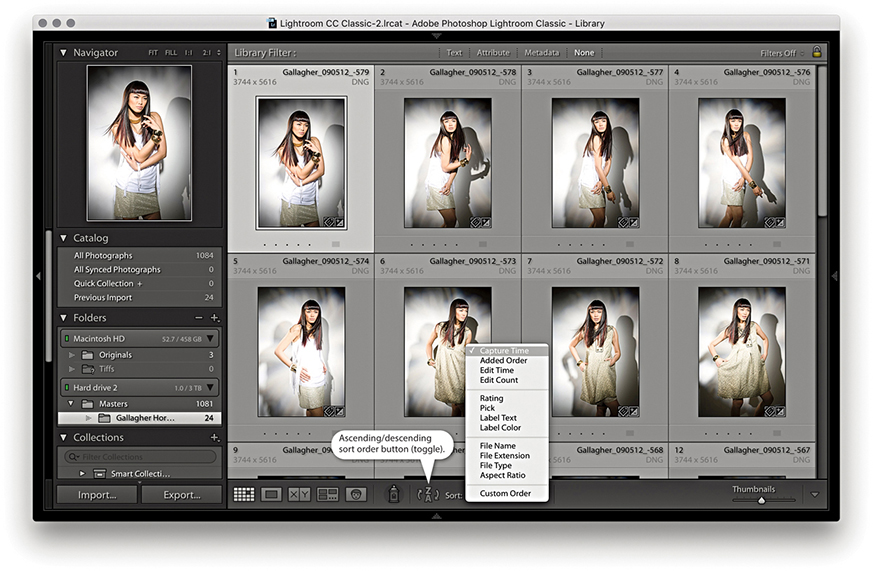

Fortunately, this process is made a lot easier in Lightroom. Figure 10.20 shows a Library Grid view of photographs that were taken at a model casting. I tend to shoot model castings with the camera tethered to the computer and update the Caption field with the model’s name and model agency as I go along. In Figure 10.20, you can see that the Caption field is currently active and I have typed in the model’s details. Instead of pressing ![]() to commit this data entry, I could use the

to commit this data entry, I could use the ![]() key (Mac) or

key (Mac) or ![]() key (PC), and a Right or Left Arrow to progress to the next or previous image. This step commits the text entry and takes you directly to the next photo. It also keeps the metadata field active so you are now ready to carry on typing in new information for the next selected photo.

key (PC), and a Right or Left Arrow to progress to the next or previous image. This step commits the text entry and takes you directly to the next photo. It also keeps the metadata field active so you are now ready to carry on typing in new information for the next selected photo.

Metadata Editing and Target Photos

If you have a group of photos currently selected and go to the Metadata panel, whenever there are varied file attributes for the selected images, the metadata information will display <mixed> values (Figure 10.21). Only those values that are common to all the selected photos (such as the copyright information) will be displayed. When you are in this default mode of operation, you can edit individual fields in the Metadata panel to update the metadata you wish to be common to all the selected files. So, for example, if you want to apply the same title to everything, you can edit the Title field, and this will update all the selected images and apply to all.

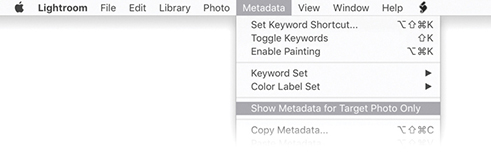

However, if Show Metadata for Target Photo Only is selected in the Metadata menu (Figure 10.22), the Metadata panel display will look like the version shown in Figure 10.23, which displays the metadata information for the most selected or target photo only, even though you may have more than one photo selected.

To show you how this feature might be used, in Figure 10.24, I selected all of the photos from a folder in the catalog. The Metadata panel displayed the information for the photo that was the most highlighted (the target photo). By using the ![]() + Arrow keys (Mac) or

+ Arrow keys (Mac) or ![]() + Arrow keys (PC), I was able to navigate from one photo to the next without deselecting the active photo selection and read the metadata information for each individual image as I did so.

+ Arrow keys (PC), I was able to navigate from one photo to the next without deselecting the active photo selection and read the metadata information for each individual image as I did so.

With the Show Metadata for Target Photo Only mode, the one thing you need to be aware of is that you will now only be able to edit the metadata on a per-image basis. This is a good thing, because it means that you can keep an image selection active and edit the metadata for each of the individual photos without losing the selection. However, many people will be accustomed to making image selections and then using the Metadata panel to edit the settings globally. So, just be aware that although this menu item can prove useful, you probably will not want to have it enabled all the time, as it could lead to confusion if you forgot this option was switched on.

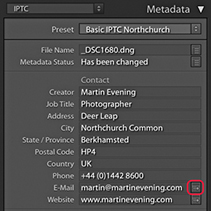

Mail and web links

You can use the E-Mail field to enter your email address. Other Lightroom users viewing your photos can simply click the action button circled in Figure 10.25 to create a new mail message to this email address using the default mail program on their computers. If the email program is not currently running, Lightroom launches it automatically.

Similarly, clicking the action button next to the Website field launches the default web browser program and takes you directly to that website. The Website field can be used to enter your usual website address. But if you wanted to, you could use this field to enter a URL that takes people to a specific page on your website. For example, you could direct people to a specific web page informing people of the types of rights that are available for certain types of images. For instance, I could broadly divide the photos in my catalog collection as photos that have been exclusively licensed, those that have non-exclusive licenses (and are available for purchase), and those that are not for sale.

Copyright status

In the Copyright Status field (Figure 10.26), you can set the copyright status as being Unknown, Copyrighted, or Public Domain. You can edit the copyright status via the Metadata panel, or go to the Metadata panel Presets menu, choose Edit Presets, and create a new custom metadata preset via the Metadata Presets dialog where Copyrighted is selected by default (Figure 10.27). If you choose to use the Copyright field only to indicate this is your copyright, this statement will be clearly understood in nearly all countries and is all that you need to do to enforce your ownership rights. You will notice that whenever you open an image in Photoshop that is marked as being copyrighted, a © symbol appears at the beginning of the filename in the document window title bar.

When viewing a photo using the IPTC Metadata panel view, the action arrow next to the Copyright Info URL takes you directly to the website link entered into the accompanying Copyright URL field.

I highly recommend that, wherever appropriate, you mark all your images as being copyrighted. You can do this by applying a metadata preset during the import process (see Chapter 2). Unfortunately, marking an image as being copyrighted will not fully protect it from becoming an orphan work. For example, if you upload your images to certain social networking sites, the copyright tag is automatically stripped, so beware. For advice on how to format a copyright notice, go to en.wikipedia.org/wiki/copyright_notice.

Keywording and Keyword List Panels

Keywording provides one of the easiest and most flexible ways to annotate your photos. In order to gain the maximum benefit, you will do well to apply a certain degree of discipline and consistency to the way you keyword your images. As I showed at the beginning of this chapter, keywording images can add value to any catalog. For professional photographers who sell photographs for a living, good keywording is essential for achieving maximum sales. For amateur photographers who are maintaining an archive of personal photographs, keywording can still add value in terms of making special photographs more easily accessible. It has taken a while to convince everyone of the importance of keywording, but now that many of us are shooting tens of thousands of photos each year, it is more important than ever to do what we can to keep our photo catalogs manageable. So, how much should you keyword? Professional colleagues of mine, such as Seth Resnick, claim that each image they supply to a picture library should have at least 50 keywords attached if it is to achieve any sales success. Seth generally carries out careful research to look for as many terms and related topics as possible for each of the images he submits. He will consider checking for variations in spelling, as well as looking out for hot topic words that might be relevant to something he has just shot. If you are not focused on library sales, then this kind of approach may seem like overkill. There is no point in overdoing things, and the key is to spend only as much time on the process of keywording as you are likely to benefit from in the future through the time saved when carrying out a file search. Okay, so it is hard to know exactly how much keywording is going to be necessary. I have to confess that I am still kind of catching up with the keywording of some of the older photos in my catalog, but I am at the stage now where every photo has at least one keyword term associated with it. But adding a few keywords that are relevant can add significant value to each image you annotate—even if it is just the photos you keep in a personal archive (Figure 10.28).

You can add keyword metadata via the Import Photos dialog as you import your images. The Figure 10.29 example shows relevant keywords being added to the Keywords field, which would then be applied to all the photos as they are imported. Lightroom can auto-complete keywords if it recognizes that the word you are typing might already belong to the keyword list.

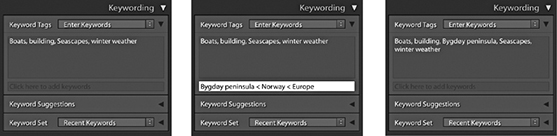

Or, you can add or edit the keywords at any time via the Keywording panel (Figure 10.30). However, I’ll first organize my keywords in the Keyword List panel into a hierarchy of keyword categories (also referred to as a controlled vocabulary). For example, in the Keyword List panel Places keyword category, I have a keyword subcategory called Europe. In Figure 10.30, I clicked in the highlighted Enter Keywords field (where it says “Click here to add keywords“) to add keywords to an image. In this instance, I wanted to add a subcategory of Europe titled Norway, and within that a subcategory: Bygdøy peninsula. The full keyword path here was: Bygdøy peninsula < Norway < Europe < Places. The keyword metadata is always entered in this hierarchical order, placing the child keyword before the parent. You will find that it pays to establish a proper keyword hierarchy that suits the content of your library and give some careful thought as to how you wish to structure a controlled vocabulary. For example, also included here were other keywords such as Seascapes < Nature subjects and Boats < Transportation.

Note

Lightroom Classic CC does not sync keywords to the cloud servers, so they won’t appear in Lightroom CC/Lightroom mobile. Similarly, keywords added via Lightroom CC will not show up in Lightroom Classic CC either. The only way to get keywords from Lightroom Classic CC to Lightroom CC is to migrate the catalog (as described in Chapter 11). During this one-time process flattened keywords are migrated to Lightroom CC.

Keywords can be used to describe anything you like. But do not forget that there are also IPTC fields that can and should be used to enter data, such as the location where a photo was shot. While keywords provide a single place for entering informational data, the fields in the IPTC data section are regarded as the formally correct place for entering such data. If you sell photos for a living, it makes sense to follow industry conventions and make sure you also fill out these sections rather than rely solely on keywording to do this.

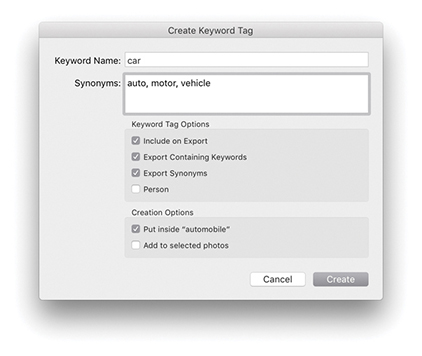

You can add keywords by clicking the plus button in the Keyword List panel, which is circled in Figure 10.31. And here, you can see I also right-clicked on the Norway keyword to reveal the context menu and chose Create Keyword Tag inside Norway. This opened the Create Keyword Tag dialog (Figure 10.32), where I added Bygdøy peninsula as a child of Norway.

When you roll over a keyword in the Keyword List panel, a check box appears to the left of the keyword. If you click this box, it adds a check mark and the keyword is added to the selected image or images (Figure 10.33). If you click the arrow to the right of the keyword count number, Lightroom filters the catalog to show all photos that share the same keyword.

If need be, you can use the Keyword List panel to manually edit the keyword list hierarchy, remove keywords that are no longer applicable, or create new hierarchy groupings. After a keyword has been added to the Lightroom keyword list, Lightroom will auto-complete keywords as you start typing in the first few letters for a new keyword entry. Apart from making it quicker to enter new data, this helps you avoid duplicating keyword entries through careless spelling or typos. Lightroom also auto-assigns the correct hierarchy. For example, the next time I might choose to add the keyword Seascapes, the Seascapes keyword will be automatically applied to the image using the Seascapes < Nature subjects keyword path (Figure 10.34). I will be coming back to this point later, but basically when you enter a keyword, Lightroom is able to auto-complete the keyword and at the same time knows to assign the correct keyword hierarchy. The only problem that can arise here is when a single keyword can have more than one context and therefore appears listed in more than one hierarchy.

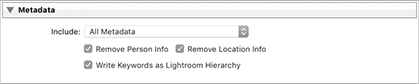

Keeping metadata private

What about metadata you might wish to keep private? As you create new keyword tags or edit existing keywords, you can deselect the Include on Export option in the Create Keyword Tag dialog (Figure 10.36). This lets you prevent specified keywords from being exported. Let’s say you have been asked to take photographs at a number of high-security locations. For your own purposes it would be useful to keyword the photos to identify where each was taken and this would help when filtering the photos in Lightroom. But your client would most likely not want you to include this particular keyword information at the export stage.

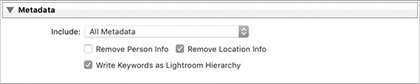

Imagine you were in the business of supplying photographic location services to clients. Figure 10.35 shows an example of an image of a holiday property, for which you might want to keep the location metadata hidden. After all, it would not be in your interests to include the exact location details within the metadata. If you use the Export dialog to export your photos, you can select the Remove Location Info box in the Metadata section to remove all GPS and IPTC location metadata. Similarly, you can also select the Remove Person Info box to exclude including People keywords (I’ll be discussing People keywords later on page 592).

Synonyms: The hidden keywords

Within keywords, it is possible to include synonyms (Figure 10.36). Synonyms are basically alternative terms that can be used in place of the main keyword, which may or may not overlap with other keyword terms. The key difference between synonyms and keywords is that synonyms, although they are searchable the same way as keywords, actually remain hidden from view in the Keywording List panel. This may seem odd, but there is a good reason for this. Basically, keeping synonyms hidden can help keep the keyword list less cluttered. However, one issue with synonyms is that when you import an image that contains a synonym (and when Export Synonyms was selected), it will be treated as a separate keyword and appear orphaned in the Keyword List panel.

In the Figure 10.36 example, the keyword car uses the following hierarchy: car < automobile < land transportation < TRANSPORTATION. Because Export Containing Keywords is selected, when any file using this keyword is exported, the full keyword hierarchy will be included. However, there are other search terms that people might want to use when searching for cars, such as auto, motor, or vehicle. These can be added as synonyms. Consequently, any image that’s tagged using the single keyword car will be discoverable using any of the following search terms: car, automobile, land transportation, transportation, auto, motor, or vehicle. The benefit of using synonyms is that they allow you to include more potential keyword search terms within a single keyword in the keyword list, but without cluttering up the entire list with lots of different keywords that are essentially variations of a single keyword term. When creating keywords for locations, if it is important that other people find your photos, there are good reasons to consider including foreign-language versions of a name in order to reach a maximum audience. For example, English speakers might search “Venice,” whereas the Italians will (correctly) search “Venezia.” When I was photographing in Scotland recently, many of the places I photographed had both English and Gaelic names. Therefore, the Gaelic versions might be suitable for inclusion as synonyms.

Applying and managing existing keywords

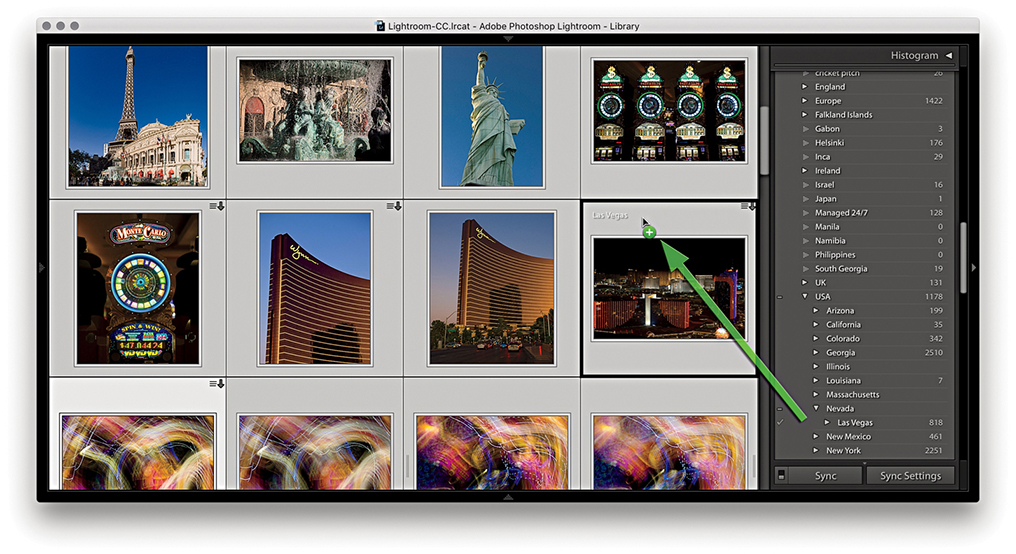

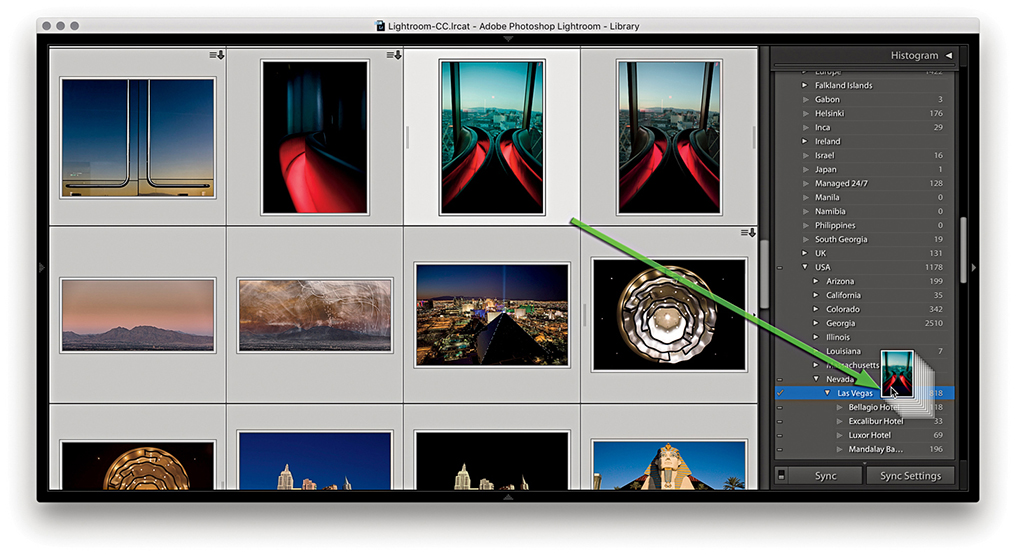

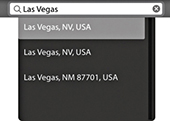

You can apply keywords to photos in the catalog in a number of ways. Figure 10.37 shows how you can apply a keyword to a selection of images by dragging a keyword to the image selection. The good thing about this method is that it is easy to hit the target as you drop the keyword. The other option is to make a selection first in the content area, and then drag the selection to the keyword. In Figure 10.38, I selected the same group of images and dragged the selection to the keyword Las Vegas.

When you select an image in the Library module, you will see all keywords associated with the photo listed in the Keywording panel, each separated by a comma. If multiple images are selected, the Keywording panel displays all the keywords that are active in the image selection. Those keywords that are common to all images in the selection are displayed as normal, while those keywords that apply only to a subselection of the images will be appended with an asterisk (Figure 10.39). If you want to unify a particular keyword across all the selected images, simply highlight the asterisk and press the ![]() key. This ensures all the selected images are now assigned with that keyword. If you want to change a particular keyword, you can always highlight it and type in a new word or press

key. This ensures all the selected images are now assigned with that keyword. If you want to change a particular keyword, you can always highlight it and type in a new word or press ![]() to remove it completely from the selection.

to remove it completely from the selection.

Auto-complete options

As you enter metadata for keywords and other editable metadata fields, it can save time to have the “Offer suggestions from recently entered values” option selected in the Catalog Settings dialog (Figure 10.95 on page 628), where you can also click the Clear All Suggestion Lists button to reset the memory and clear all memorized words. If you begin typing a keyword that has two or more possible sources, Lightroom will offer them as choices. I will discuss the reasons for this later in the implied keywords section on page 588.

Most of the time, auto-completion is a useful thing to have active. Sometimes, however, it can become a pain. For example, when I do a model casting and enter the names of models in the Caption field of the Metadata panel in the Library module, I don’t find auto-completion particularly helpful. What is useful with the Mac version is the ability to spell-check. The Edit ![]() Spelling submenu in the Library module contains the options Show Spelling and Grammar, Check Spelling, and Check Spelling as You Type. This can help you avoid mistakes as you add new metadata.

Spelling submenu in the Library module contains the options Show Spelling and Grammar, Check Spelling, and Check Spelling as You Type. This can help you avoid mistakes as you add new metadata.

Removing keywords

It is easy enough to remove keywords. You can go to the Keyword List panel, select the keyword or keywords you want to delete, and click the minus button at the top of the panel. This deletes the keyword from the Keyword List panel’s hierarchical list and also removes it from any photos that have had the keyword assigned to them. Understand though that when you remove a keyword via the Keyword List panel, you are deleting it from the Lightroom database only. If keyword metadata has already been saved to the file’s XMP space and you need to maintain compatibility with Bridge, you will want to force-save the metadata change (the keyword deletion) back to the file’s XMP space by choosing Metadata ![]() Save Metadata to Files. By the same token, if specific keywords are removed using an external program, those keywords will not appear removed when you view the photo in Lightroom until you explicitly read the revised metadata back from the image.

Save Metadata to Files. By the same token, if specific keywords are removed using an external program, those keywords will not appear removed when you view the photo in Lightroom until you explicitly read the revised metadata back from the image.

As photos are removed from the catalog, keywords that were formerly associated with those images will consequently become unused. You can remove these by selecting and deleting as I have just described, or clear them from the Keyword List panel. To do this, go to the Metadata menu and choose Purge Unused Keywords. Just so you don’t remove these keywords by accident, a warning dialog will ask you to confirm this action.

Keyword hierarchy

It is important to plan the keyword hierarchy you are going to use by adopting what is known as a controlled vocabulary of keywords. You can edit the keyword list by dragging the keywords into different keyword categories. It is possible to have several tiers of subcategories. For example, you could organize place name keywords in the following order: Town/City < State < Country < Places. When you are working in the Keywording panel, you can enter new keywords and assign a hierarchy by including a < character after the keyword, followed by the category. So, if you wanted to add a new keyword called elephants as a subcategory of mammals, vertebrates, and ANIMALS, you would type elephants < mammals < vertebrates < ANIMALS (or you could type ANIMALS > vertebrates > mammals > elephant). When you press ![]() , you will see the elephants keyword appear as a new subset keyword in the Keyword List panel. There are a few things to point out here. One is that you always enter new keywords using the above path directory methods. Second, once you have established a basic hierarchy, there is no need to type a complete path each time. In other words, once you have created the above path hierarchy to add, say, cat as a keyword, you do not have to type cat < mammals < vertebrates < ANIMALS. All you will need to type is cat or maybe cat < mammals, and Lightroom will know how to complete the remaining hierarchy.

, you will see the elephants keyword appear as a new subset keyword in the Keyword List panel. There are a few things to point out here. One is that you always enter new keywords using the above path directory methods. Second, once you have established a basic hierarchy, there is no need to type a complete path each time. In other words, once you have created the above path hierarchy to add, say, cat as a keyword, you do not have to type cat < mammals < vertebrates < ANIMALS. All you will need to type is cat or maybe cat < mammals, and Lightroom will know how to complete the remaining hierarchy.

How you categorize library images is entirely up to you, but if you submit work to an external photo library, you will most likely be given guidelines on the acceptable keywords and categories to use when keywording photographs for submission. These guidelines are normally supplied privately to photographers who work directly with the picture agencies, but there are online resources you can refer to that describe how best to establish and work with a controlled vocabulary. These ensure the keyword terms you use to describe your images conform to prescribed sets of words that are universally used by others working in the same branch of the photo industry. When you get into complex keywording, it is important to be methodical and precise about which terms are used and the hierarchy they belong to.

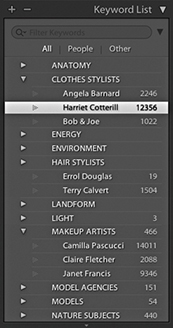

Keyword categories can also be used to catalog images in ways that are helpful to your business. For commercial shoots, I find it is useful to keep a record of who has worked on which shot. Some catalog programs let you set up a custom database template with user-defined fields. In Lightroom, you can set up keyword categories for the various types of personnel and add the individual names as a subset (or child) of the parent keyword category. Figure 10.40 shows how I have created keyword categories for Clothes stylists, Hair stylists, and Makeup artists. Within these categories I created subcategories of keywords listing the people I have worked with regularly. As I start typing in someone’s name as a new keyword entry, if Lightroom recognizes this as a possible match to one of the existing keywords in the keyword database, it auto-completes the keyword metadata entry in addition to correctly placing the keyword within the established hierarchy. This type of organization is also useful for separating library images by job/client names. When the keyword names are in place, you should find it fairly easy to keep your catalog of images updated.

Keyword filtering

The Keyword List panel can easily grow to contain hundreds of keywords. You can simplify the navigation by typing the keyword you are searching for in the Filter Keywords section at the top of the panel. Even if you type just the first few letters, this can help narrow the selection of keywords to choose from. You can use this feature to check if a keyword exists in more than one place and edit the keyword list accordingly. The filter options allow you to filter by All keywords, by People keywords, or by Other (exclude People keywords). If you click on the down arrow beside the magnifier in the Filter Keywords box (circled in Figure 10.41), you can select Show Keywords Inside Matches. This is helpful when you also want to show all the child keywords of the ones you have filtered.

You can also use the Keyword List panel to filter the photos that appear in the content area. As you roll over a particular keyword, you will see an arrow appear next to the keyword count number. When you click the arrow, this displays all the photos in the Lightroom catalog containing that keyword, regardless of whatever photo filter view you have currently active.

Importing and exporting keyword hierarchies

You can create your own keyword hierarchy from scratch or import one that has already been created (as in the Figure 10.41 example). To import keywords into Lightroom, you’ll need to do so from a tab-delimited keyword file. This is a plain text file with a tab between each indented level in the text so the data is arranged in a hierarchical format. David Riecks runs a website with tips and guidelines on how to work with a controlled vocabulary at controlledvocabulary.com, where you can purchase a ready-made vocabulary that is compatible with Lightroom. To install it, download the file, launch Lightroom, choose Import keywords from the Metadata menu, and select the file. That’s it—these keywords will be added to the Keyword List panel. Similarly, you can export a keyword hierarchy for sharing on other computer systems or catalogs by choosing Metadata ![]() Export Keywords. Likewise, this exports the keyword list as a text file using a tab-delimited format.

Export Keywords. Likewise, this exports the keyword list as a text file using a tab-delimited format.

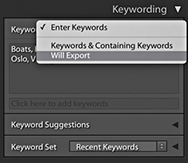

Implied keywords

The Keywording panel lists keywords that have been applied explicitly to images via the Keyword Tags section. But as I mentioned, some of the keywords you enter will already have implicit keywords associated with them. So, if in the future, I apply the keyword Bygdøy peninsula, it will automatically include the implicit keywords: Places, Europe, and Norway. I don’t have to type in Bygdøy peninsula < Norway < Europe < Places if there is already a keyword with such a hierarchy in the database. It should only be necessary to type in the first few letters, such as Byg, and Lightroom will auto-complete the rest. If the Keyword Tags menu is set to display Enter Keywords (Figure 10.42), you can edit the keywords in this mode, but the implicit keywords will be hidden (although they will nonetheless remain effective when conducting searches). If you select Keywords & Containing Keywords or Will Export (Figure 10.43), you will see a flattened list of keywords that includes the implicit keywords, but you will not be able to edit them in the Keywording panel when using these two modes.

When you enter a new keyword, you use the < key to signify that this keyword is a child of the following keyword (such as train < land transportation < Transportation). This establishes the hierarchy, and as I explained, when you use the Enter Keywords mode, all you will see is the first keyword, and the parent keywords will be hidden. However, if you apply a keyword that is identical to another keyword but both have different parents, you will then see the full keyword path hierarchy appear in the Keywording dialog. For example, in Figure 10.44, you have two options for the Keyword Camilla Pascucci, because I added the keyword Camilla Pascucci in two separate contexts. In one context, Camilla Pascucci is a makeup artist I work with, but she is also my wife (so she can also be listed as a subset of PEOPLE as someone I know). This is why when you type in certain keywords, you will sometimes see more than one keyword path suggestion. It also explains why, when after you press ![]() to okay the choice, you may see a full keyword path directory in the Keywording panel rather than a single keyword.

to okay the choice, you may see a full keyword path directory in the Keywording panel rather than a single keyword.

Keyword suggestions

Expanding the Keyword Suggestions section reveals a number of suggested keywords. You can click on any of the keywords displayed here to add these to a selected photo or photos. When you select an image, Lightroom adapts the list of keywords that are available for use based upon the keywords already in neighboring images that have been captured around the same time. The suggested keywords are also prioritized based on how soon before or after the current photograph they were taken. The system works well when trying to guess what other keywords you might like to add to a particular photograph. In Figure 10.45, the selected image had the keywords Las Vegas, night, and Paris Hotel. From this, the Keyword Suggestions section was able to suggest adding other keywords such as Bellagio Hotel, Luxor Hotel, and MGM Hotel. These were common keywords that had been assigned to photos taken close to the time the selected image was captured. The more keywords you have in the source photo or neighboring photos, the more accurate the suggested keywords will be. The diversity of your keywording will also count. If all the keywords in a set of images are nearly identical, there is not much Lightroom can do when it comes to suggesting alternatives.

Keyword sets

The Keywording panel can also be used to display sets of keywords. When keywording certain types of photo projects, it can save you a lot of time to have commonly used keywords made quickly accessible. Keyword sets offer a quick method for adding commonly used keywords to selected images. To access a keyword set, click the disclosure triangle (circled in Figure 10.46) to reveal the Keyword Set section options. This will normally display the Recent Keywords keyword set, which, as I just showed, can be useful for most keywording jobs. Or, you can select one of the supplied keyword set presets such as Outdoor Photography, Portrait Photography, or Wedding Photography. In Figure 10.46, the Outdoor Photography keyword set was selected, offering suitable, outdoor keyword suggestions such as Landscape and Wildlife. Clicking the keyword set keyword suggestions is a toggle action. You can click once to add a keyword and click again to remove it. You can also use the ![]() key plus a number as a shortcut for assigning keyword set keywords. If you hold down the

key plus a number as a shortcut for assigning keyword set keywords. If you hold down the ![]() key, the number shortcuts will appear next to each keyword. So, for example, if I wanted to assign the Landscape keyword, I would use the

key, the number shortcuts will appear next to each keyword. So, for example, if I wanted to assign the Landscape keyword, I would use the ![]() shortcut (Figure 10.47).

shortcut (Figure 10.47).

Creating your own custom keyword sets

1. To create a custom keyword set, go to the Keyword Set section of the Keywording panel and click “Edit set.” This opens the Edit Keyword Set dialog using the current keyword set list. Just replace these with the keywords you would like to use when keyword-editing a particular project. Here, I created a keyword set that I could use when editing photographs taken in the Antarctic.

2. After you create a new custom keyword set, the keywords appear listed in the Metadata panel in the Keyword Set section. You can hold down the ![]() key to preview the keyboard shortcuts and use the

key to preview the keyboard shortcuts and use the ![]() key plus a number to quickly assign any of these keywords to selected photos.

key plus a number to quickly assign any of these keywords to selected photos.

If you have lots of photos to edit from a specific trip or you regularly photograph certain types of events, you may find it useful to create your own keyword sets for these types of shoots.

Tip

When the Painter tool is set to Target Collection mode, it can be used to add photos to whatever is the current target collection. This is normally the Quick Selection in the Catalog panel, but you can change this to any collection you like.

The Painter Tool

The Painter tool is located in the Library module Toolbar (Figure 10.48). It can be activated by clicking the tool, which will float it from its docked position. You can also access the Painter tool by going to the Metadata menu and choosing Enable Painting, or use the ![]() (Mac) or

(Mac) or ![]() (PC) shortcut.

(PC) shortcut.

You can then select which type of settings you want to apply with the Painter tool. The Painter tool is ideal for those times when you may want to repeatedly apply a keyword or combination of keywords to photos in the Library module Grid view. You can do this by clicking with the Painter tool on a photo, or you can click and drag over a number of photos at once. But as well as that, you can use the Painter tool to paint using labels, flags, ratings, metadata, Develop settings, or rotation settings, as well as add to the target collection. You can also load keywords from any of your keyword sets. To do this, hold down the ![]() key with the Painter tool selected to pop open the keyword sets list, select a desired keyword set, and then click individual keywords to add these to the keyword painter list. In Keywords mode, you can enter more than one single keyword into the Paint field. You will also notice in the Keyword List panel that keywords entered this way will appear with a + sign next to them.

key with the Painter tool selected to pop open the keyword sets list, select a desired keyword set, and then click individual keywords to add these to the keyword painter list. In Keywords mode, you can enter more than one single keyword into the Paint field. You will also notice in the Keyword List panel that keywords entered this way will appear with a + sign next to them.

The Painter tool appearance varies according to which mode you have selected. Figure 10.49 shows examples of all the different styles. As you can see, there are lots of potential uses for this tool—not just applying keywords, but other tasks such as painting with a saved Develop setting. To undo a Painter tool–applied setting, you need to hold down the ![]() key as you click to switch to the Eraser mode (

key as you click to switch to the Eraser mode (![]() ), which will undo a setting. Also keep in mind that you have to be careful to target the thumbnail and not just the cell area. For jobs where you are constantly applying the same instruction, like “rotate this photo 90 degrees” or “apply this set combination of keywords,” the Painter tool does have its uses, but it can often be much easier to just select the photos first and then apply a setting to all the photos in one step.

), which will undo a setting. Also keep in mind that you have to be careful to target the thumbnail and not just the cell area. For jobs where you are constantly applying the same instruction, like “rotate this photo 90 degrees” or “apply this set combination of keywords,” the Painter tool does have its uses, but it can often be much easier to just select the photos first and then apply a setting to all the photos in one step.

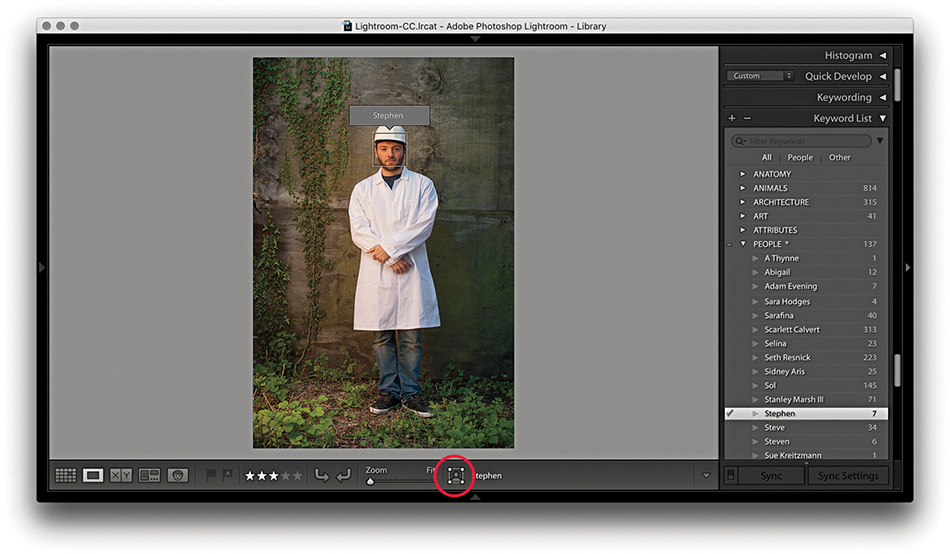

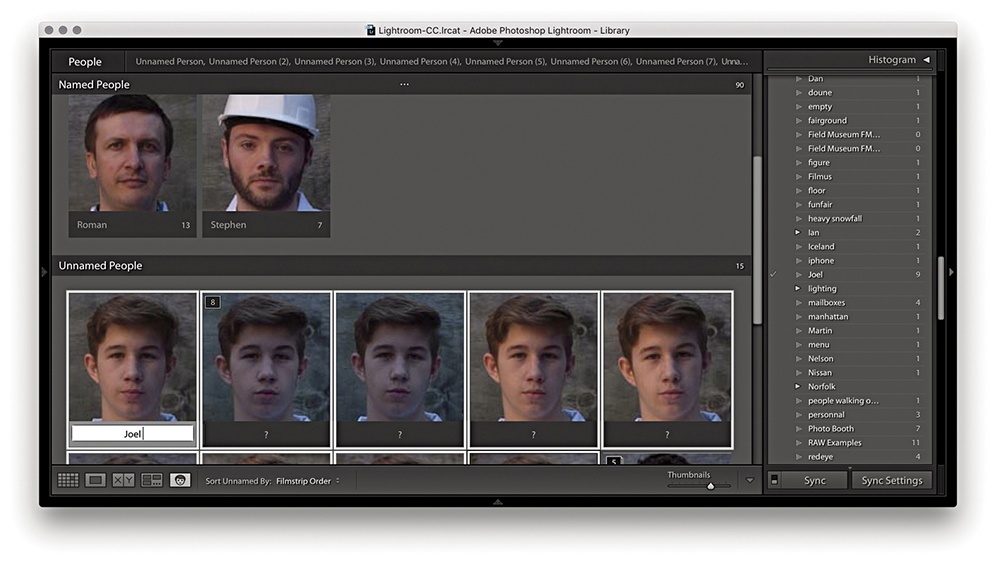

People View Mode

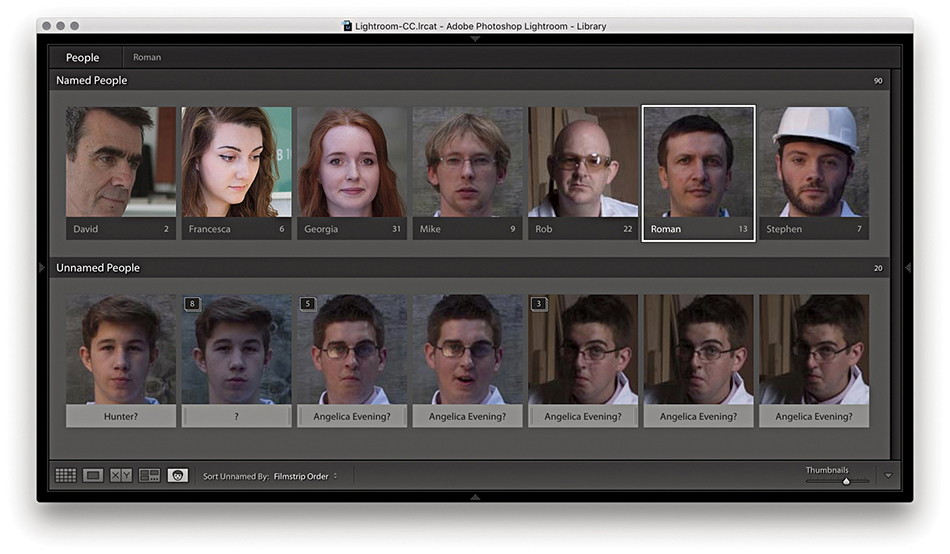

The face-tagging feature automatically identifies faces in the catalog images, adding face regions to individual photos. It can be trained to recognize named individuals and then to create and automatically add Person keywords to the Keyword List panel inside a designated parent keyword.

Before Lightroom can identify and recognize face shapes in each image, however, the photos in the catalog (or Filmstrip selection) must be indexed. During this stage, Lightroom builds a record of each image in a form that the face-recognition engine can use to detect and analyze faces in images. Indexing can be turned on for the whole catalog by checking the “Automatically detect faces in all photos” option in the Catalog Settings Metadata section, or you can click the Identity Plate to open the Activity Center and enable Face Detection. For photos that are currently offline, Lightroom automatically indexes them the next time they come back online and Lightroom is launched. If indexing is turned off, Lightroom indexes the selected source only when you enter the People view or you activate the Draw Face Region tool in the Loupe view for the current photo. For example, it can be useful to index faces for family and portrait photos of known people, but less so if you have photographs recording an event where there may be lots of unknown faces in a crowd. Therefore, it can pay to be selective about which photos you choose to index and those you don’t.

Tip

To trigger a face detection run again, select the photos, do a batch rotation, and then rotate them back.

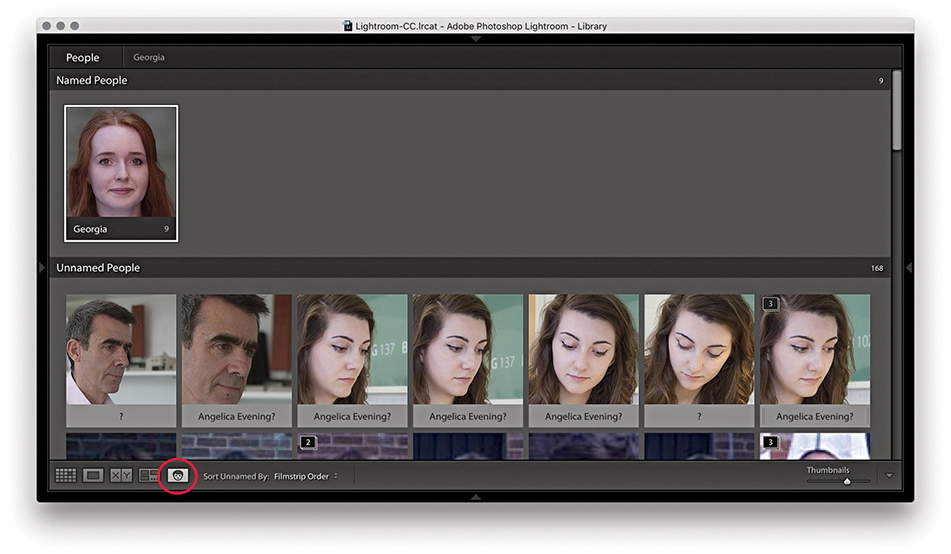

When the initial indexing is complete, you can click the People button in the Library module Toolbar to go to the People view mode (click again to toggle returning to the Grid view). Or, choose View ![]() People or use the

People or use the ![]() shortcut. Once in the People view mode, Lightroom displays face thumbnails in the Unnamed People section showing all the possible face matches for that particular selection of images. If you hold down the

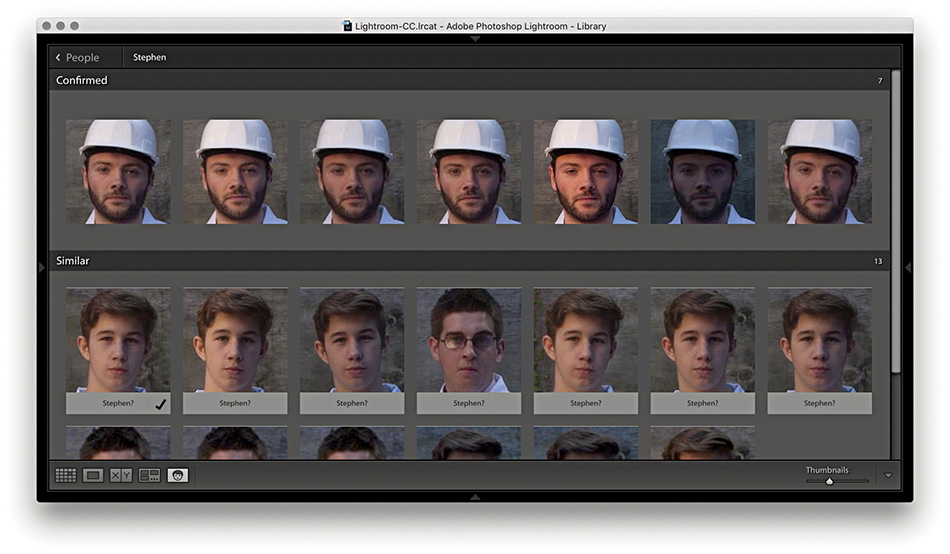

shortcut. Once in the People view mode, Lightroom displays face thumbnails in the Unnamed People section showing all the possible face matches for that particular selection of images. If you hold down the ![]() key and pan the pointer over a face stack, it shows a preview of all the faces that are in that stack. From there, it is up to you to identify the faces and enter the names manually. As you identify each face, Lightroom will attempt to identify similar faces. You can then click to approve the name suggestions as being correct, or rename them correctly.

key and pan the pointer over a face stack, it shows a preview of all the faces that are in that stack. From there, it is up to you to identify the faces and enter the names manually. As you identify each face, Lightroom will attempt to identify similar faces. You can then click to approve the name suggestions as being correct, or rename them correctly.

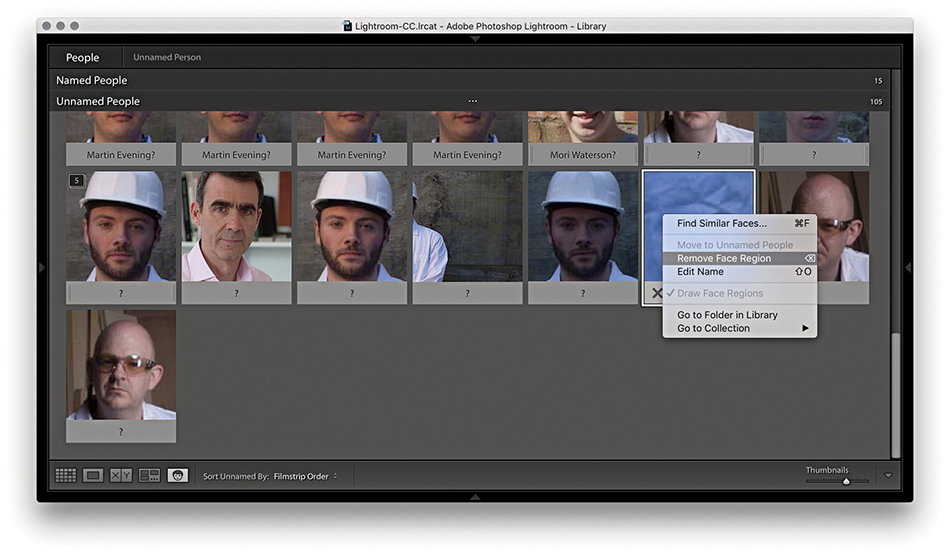

In Loupe view with the Draw Face Region tool active, face regions overlay each recognized face. For a photograph with a group of people, Lightroom will not just suggest the names of the people featured in the photo, but will identify each face individually. Lightroom seems mostly able to spot faces. On the other hand, it can still miss obvious matches, or incorrectly include all kinds of picture elements as faces, but you can always choose to delete the face region for such photos to remove them from the equation. In practice, you will have to decide whether the effort of all this training work is worth it compared to the manual method of visually identifying people and manually entering keywords. Ultimately, face-tagging requires a significant amount of user input in the early stages in order to familiarize Lightroom with the people you photograph most often. The more you use this feature, though, the easier it becomes for Lightroom to automatically recognize the people seen in your photographs and name and keyword them automatically.

You can monitor the indexing progress via the Activity Center. The indexing process involves reading the raw data from disk. Even if you happen to be doing something else that involves reading the raw data, such as converting to DNG, or building Smart Previews, the indexing process can happen simultaneously and get a free ride. Plus, the index will build faster if you have Smart Previews available. Failing that, if there are embedded previews that are sufficiently large enough (greater than 1024 pixels along the longest edge), Lightroom will use those. Face info search data is also included when importing from another catalog and when creating a virtual copy.

It is worth pointing out here that the underlying face-tagging engine in Lightroom has been significantly updated. The new face engine does a better job of picking up faces that the old engine might have missed and improves a little bit on detecting faces in profile. If you are working with a catalog that has already been face-indexed, Lightroom is able to re-index photographs that have existing face regions. These are the square overlays that appear in the Loupe view when the Draw Face Region button is activated in the Toolbar. The Face Regions are preserved while Lightroom recomputes the underlying face descriptor files that are used in face recognition. To initiate this, see the section below.

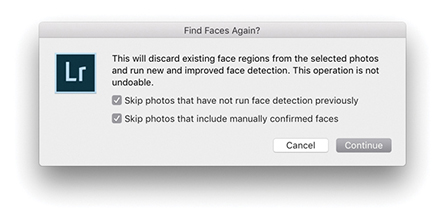

Find Faces Again

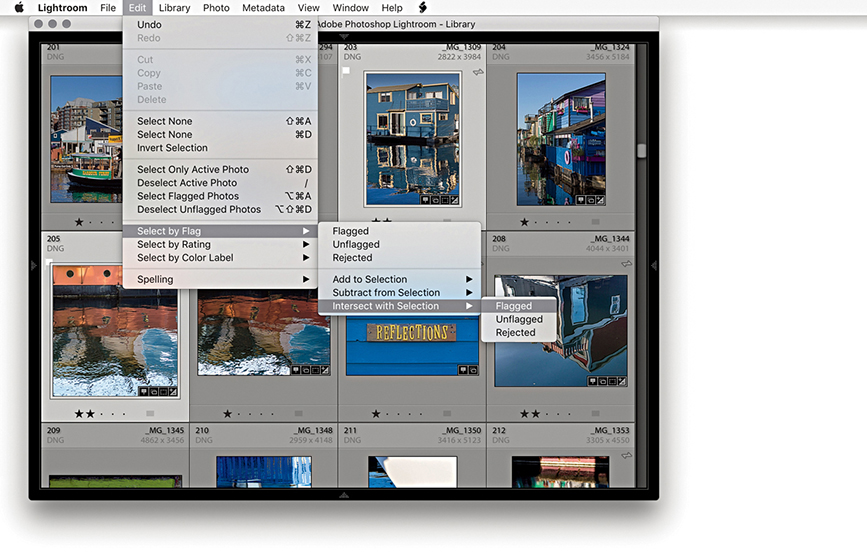

To reindex everything, first go to the Library module Catalog panel and click All Photographs. Next, select Edit ![]() Select All to select all the photos in the Grid view or the Filmstrip. Having done that, choose Library

Select All to select all the photos in the Grid view or the Filmstrip. Having done that, choose Library ![]() Find Faces Again to pop open the Find Faces Again dialog (Figure 10.50). Here, you can choose to “Skip photos that have not run face-detection previously.” In this case, the reindexing process should not take too long, as Lightroom is only computing the face descriptors for already-indexed files, rather than analyzing the catalog all over again. However, until that process has been completed, you will see only those photos that have been reindexed using the new Face engine when carrying out a faces search. The other option is to “Skip photos that include manually confirmed faces.” This preserves all manually confirmed faces and does not reindex such photos all over again.

Find Faces Again to pop open the Find Faces Again dialog (Figure 10.50). Here, you can choose to “Skip photos that have not run face-detection previously.” In this case, the reindexing process should not take too long, as Lightroom is only computing the face descriptors for already-indexed files, rather than analyzing the catalog all over again. However, until that process has been completed, you will see only those photos that have been reindexed using the new Face engine when carrying out a faces search. The other option is to “Skip photos that include manually confirmed faces.” This preserves all manually confirmed faces and does not reindex such photos all over again.

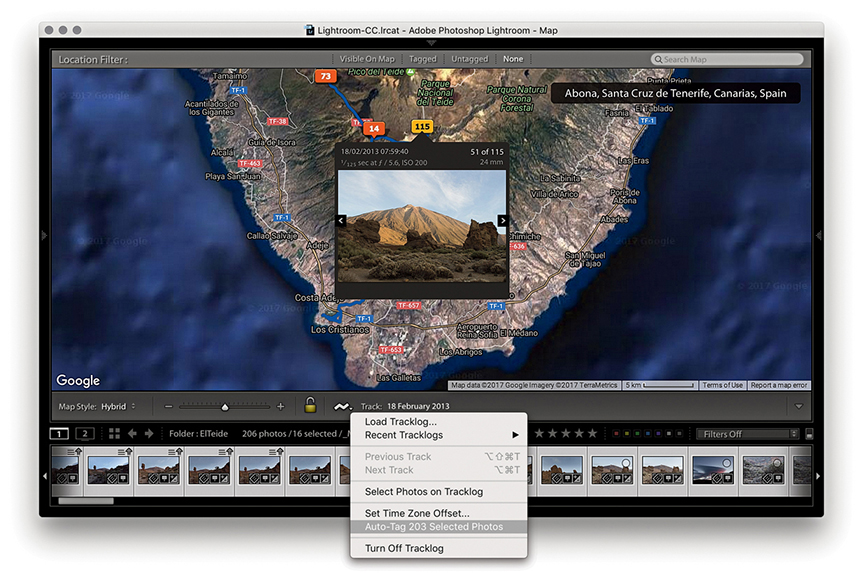

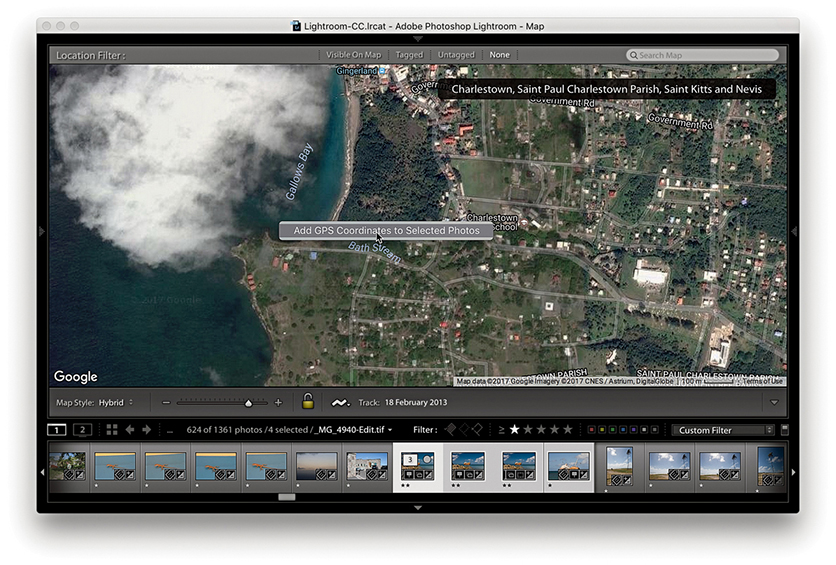

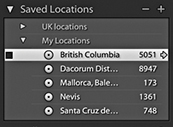

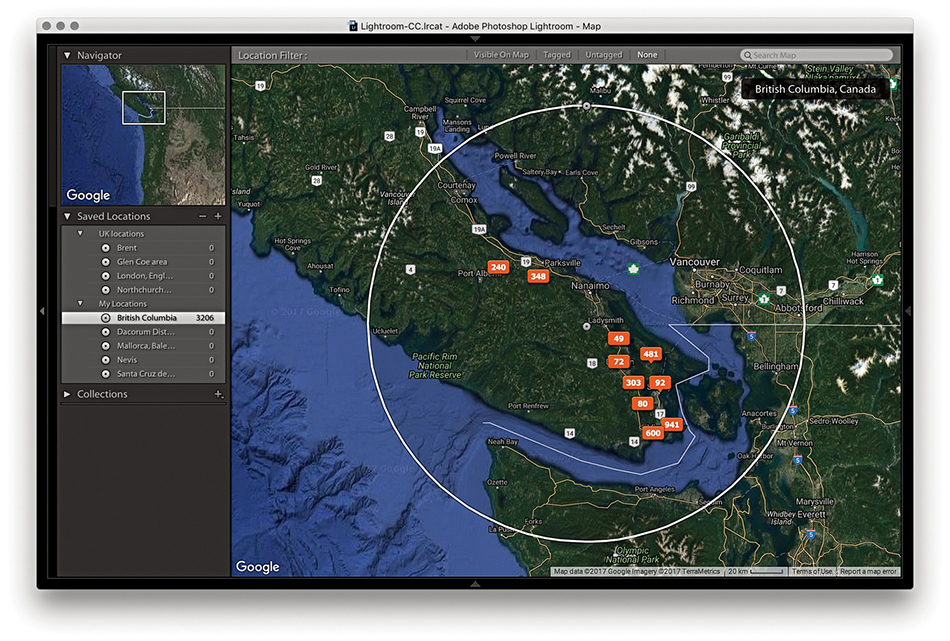

Newly imported photos are analyzed for both the face detection and face recognition stages (providing face indexing is turned on for the catalog and the face regions have not simply been imported from the XMP).