CHAPTER 8

Income Approaches

The income approach is the workhorse of the valuation profession. In the income approach, the estimated cash flow is divided by a capitalization rate in the capitalization of earnings method, or discount rate in the discounted cash flow method to estimate the value.1 These are the two primary income methods.

The two primary income methods will be reviewed back and forth in steps throughout the chapter. This is because many of the steps have similarities and build on one another. We start with a discussion of some critical issues about the income method that only applies to very small businesses. Then we will look at estimating cash flows under the two approaches including tax affecting and other adjustments. Subsequently we will estimate a discount rate and follow with the further adjustments to estimate a capitalization rate. Next we will complete the capitalization of earnings estimate and then discuss a few variations of that method. Finally, we will complete the discounted cash flow estimate to determine the appraisal.

A complete calculation including estimating the cash flow, calculating the discount or capitalization rate, and then completing the estimates is shown in Figure 8.3 on p. 163 for the capitalization of earnings and in Figure 8.15 on p. 213 for the discounted cash flows method. Refer back to these frequently. In fact, if this material is new to you, it may be easiest to go to the website and review the related Excel files including looking at the formulas. Then print the files and make notes on the printout when going through this chapter.

The income method's main variance from the market method is that instead of a market multiplier determined from comparable transactions, a discount rate for forward-looking cash flows or capitalization rate applied to adjusted historic cash flows is determined by looking at the relative risk of this investment to other available investments to investors.

“There are three main components that need to be investigated to use the income approach:2

- What is the cash flow and is it reliable and predictable?

- How is the cash flow going to grow and how do we estimate a growth rate?

- How risky is this investment compared to all other investments available?”

An essential element in applying the income method is to make sure the income stream is properly aligned with the calculated discount rate.3 “Apples to apples,” while this seems simple, it often is not.

There are many different cash flows. Revenues, gross profit, EBITDA, EBIT, after-tax cash flow, net income, cash flow to equity, cash flow to invested capital, and so on. Each may call for a different estimated discount rate. The valuation will be wrong if an improper alignment between cash flow and discount rates is used.

Another issue related only to very small businesses is, are there really investors for this business?

WHO IS AN “INVESTOR”?

A primary difference between the market approach and the income approach is that the income approach is “value to the investor.” This is often conveniently overlooked when valuing very small businesses.

For many small businesses, particularly those with less than $1,000,000 of earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization (EBITDA), there is a limited “investor” market. There are mainly owner-operators; namely, people buying jobs hopefully with opportunity. Owner-operators can be considered investors but they need compensation. The mix of compensation for labor vs. return for investment is very murky and with very small businesses often inseparable. As a practical matter, this problem gets bigger as EBITDA or other cash flows get smaller. At $500,000 of EBITDA, there are almost no third-party investors other than family members and loved ones. These businesses and smaller businesses are typically purchased by owner/operators and financed using small business administration (SBA) loans.

What this creates for valuators who insist on using the income method for smaller businesses is either converting to seller's discretionary earnings (SDE) instead of after-tax cash flow or EBITDA. SDE cannot be tied into any method of estimating a capitalization or discount rate except maybe the guess method. (Or a back-door market method, but then it would be better to just be honest and do a proper market analysis.)

Or, valuators are presented with the unsupportable but true possibility that very small businesses have much lower discount rates than larger businesses. (Supply and demand could explain it, after all there are many more people who can afford a $100,000 value business than a $50,000,000 value business.) But, that goes against “common knowledge” and logic. See Figure 8.1 for an analysis of increasing discount rates necessary to value very small businesses.

To restate, as the cash flow goes below $500,000 EBITDA, it becomes very difficult to determine EBITDA, as it is hard to estimate the employment value of an owner-operator of a small enterprise. Yet this can have a very large effect on the value found.

| SDE | $100,000 | $200,000 | $300,000 | $400,000 | $500,000 | $600,000 | $700,000 | $800,000 | $900,000 | $1,000,000 | $1,100,000 | |

| Reasonable Salary | $150,000 | $150,000 | $150,000 | $150,000 | $150,000 | $150,000 | $150,000 | $150,000 | $150,000 | $150,000 | $150,000 | |

| EBITDA | ($50,000) | $50,000 | $150,000 | $250,000 | $350,000 | $450,000 | $550,000 | $650,000 | $750,000 | $850,000 | $950,000 | |

| SDE Market Multiplier | 2.5 | |||||||||||

| SDE Value Estimate | $250,000 | $500,000 | $750,000 | $1,000,000 | $1,250,000 | $1,500,000 | $1,750,000 | $2,000,000 | $2,250,000 | $2,500,000 | $2,750,000 | |

| Implied EBITDA | ||||||||||||

| Discount Rate (%) | 10.00 | 20.00 | 25.00 | 28.00 | 30.00 | 31.43 | 32.50 | 33.33 | 34.00 | 34.55 |

Note:

This chart shows the “Implied” Discount rate as businesses get very small. Note how the rate drops precipitously.

While a simplification, this chart clearly shows problems with the model as business value drops below $2,000,000 and even more so under $1,000,000 of value.

FIGURE 8.1 Comparable “Required” Discount Rate After Tax Cash Flow Drops

Unlike large companies, there is limited data on the employment value of a leader of small businesses who works 55 + hours a week, rarely takes vacations, and also often has very high-level technical skills across the many situations that arise in a small business. He or she knows they are making $500,000 a year in total. They choose to grow their business by reinvesting some of this capital and are still well compensated, particularly compared to their other likely choices. But how much of that is for replaceable management and other measurable labor tasks versus how much is really profit for owning a business? How do we even define the job? Further, this theory is at least supported by the anecdotal common belief that, as businesses grow, usually three distinct skill sets and people are hired to replace what the owner has been doing: sales, finance/accounting, and operations.

Clearly as EBITDAs and after-tax cash flows increase the risk of the error in estimating owner's compensation decreases. For one thing, as companies get larger, there may be more accurate data. Additionally, simply because the likely range of owner compensation becomes a smaller part of the overall cash flow, the risk of significant error in this adjustment drops. Figure 8.2 shows the effect of the difference between $100,000 and $150,000 of reasonable compensation on the “required” implied capitalization rates as companies get very small.5 The variance on the discount rate to find the likely correct value is huge. (I say this as small businesses DO sell on their SDE value. This is a fact.) Note how at higher values, (approximately $1,500,000 of value in this case), the variance created by a $50,000 salary difference becomes manageable.

| 1 | SDE | $100,000 | $200,000 | $300,000 | $400,000 | $500,000 | $600,000 | $700,000 | $800,000 | $900,000 | $1,000,000 | $1,100,000 | |

| 2 | Reasonable Salary | $100,000 | $100,000 | $100,000 | $100,000 | $100,000 | $100,000 | $100,000 | $100,000 | $100,000 | $100,000 | $100,000 | |

| 3 | EBITDA | $0 | $100,000 | $200,000 | $300,000 | $400,000 | $500,000 | $600,000 | $700,000 | $800,000 | $900,000 | $1,000,000 | |

| 4 | |||||||||||||

| 5 | SDE Market Multiplier | 2.5 | |||||||||||

| 6 | SDE Value Estimate | $250,000 | $500,000 | $750,000 | $1,000,000 | $1,250,000 | $1,500,000 | $1,750,000 | $2,000,000 | $2,250,000 | $2,500,000 | $2,750,000 | |

| 7 | |||||||||||||

| 8 | Implied EBITDA | ||||||||||||

| 9 | Discount Rate (%) | 20.00 | 26.67 | 30.00 | 32.00 | 33.33 | 34.29 | 35.00 | 35.56 | 36.00 | 36.36 | ||

| 10 | |||||||||||||

| 11 | |||||||||||||

| 12 | SDE | $100,000 | $200,000 | $300,000 | $400,000 | $500,000 | $600,000 | $700,000 | $800,000 | $900,000 | $1,000,000 | $1,100,000 | |

| 13 | Reasonable Salary | $150,000 | $150,000 | $150,000 | $150,000 | $150,000 | $150,000 | $150,000 | $150,000 | $150,000 | $150,000 | $150,000 | |

| 14 | EBITDA | ($50,000) | $50,000 | $150,000 | $250,000 | $350,000 | $450,000 | $550,000 | $650,000 | $750,000 | $850,000 | $950,000 | |

| 15 | |||||||||||||

| 16 | SDE Market Multiplier | 2.5 | |||||||||||

| 17 | SDE Value Estimate | $250,000 | $500,000 | $750,000 | $1,000,000 | $1,250,000 | $1,500,000 | $1,750,000 | $2,000,000 | $2,250,000 | $2,500,000 | $2,750,000 | |

| 18 | |||||||||||||

| 19 | Implied EBITDA | ||||||||||||

| 20 | Discount Rate | 10.00% | 20.00% | 25.00% | 28.00% | 30.00% | 31.43% | 32.50 | 33.33% | 34.00% | 34.55% | ||

| 21 | |||||||||||||

| 22 | Discount Rate Variance | 10.00% | 6.67% | 5.00% | 4.00% | 3.33% | 2.86% | 2.50 | 2.22% | 2.00% | 1.82% | ||

| 23 | |||||||||||||

| 24 | Percentage Difference | 20/22 | 100.00% | 33.33% | 20.00% | 14.29% | 11.11% | 9.09% | 7.69 | 6.67% | 5.88% | 5.26% | |

Notes:

This chart shows the relationship between selecting replacement labor value and EBITDA with smaller businesses. Note not only the high implied discount rates (the bottom half of the chart is the same as Figure 8.1) but the large swing in implied discount rates at lower business values.

Replacement Salary is shown at $100,000 on the top chart and $150,000 on the lower chart. Discount Rate Variances are shown at the bottom.

At higher cash flows, SDE multipliers will be higher and become less likely to be the correct valuation multiplier. Yet, the problem illustrated at low values is very real.

FIGURE 8.2 Impact of Reasonable Compensation in Very Small Companies

As EBITDA and after-tax cash flows increase, the income method becomes more reliable. If adequate market data exists for small and very small businesses, the market method generally should be the preferred method. But, certainly, the income method is an important secondary method.

For this reason, once cash flow is over $500,000 SDE, the market method using EBITDA and the income methods should be more closely analyzed. (This is also a requirement of Valuation Standards for opinions of value, all valuation methods should be considered.)6

CASH FLOW FOR INCOME APPROACHES

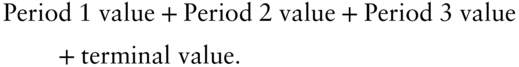

Estimating the future cash flow is the first major component of the income method. The two main income methods are the discounted cash flow and the capitalization of earnings. The major difference in the two methods is how the future cash flows are forecast.

In the discounted cash flow method, a portion of the future, often three to ten years, is forecast. Growth is part of the forecast and can vary in each forecast year. This method is often used when early cash flows are going to vary significantly from future cash flows. A steady growth rate is then estimated to calculate the growth in the remaining cash flows used to perpetuity. Perpetuity is a ‘long business period’ that contemplates the highs and lows of operations over time. It is likely not to be the year-over-year growth in forecast periods.

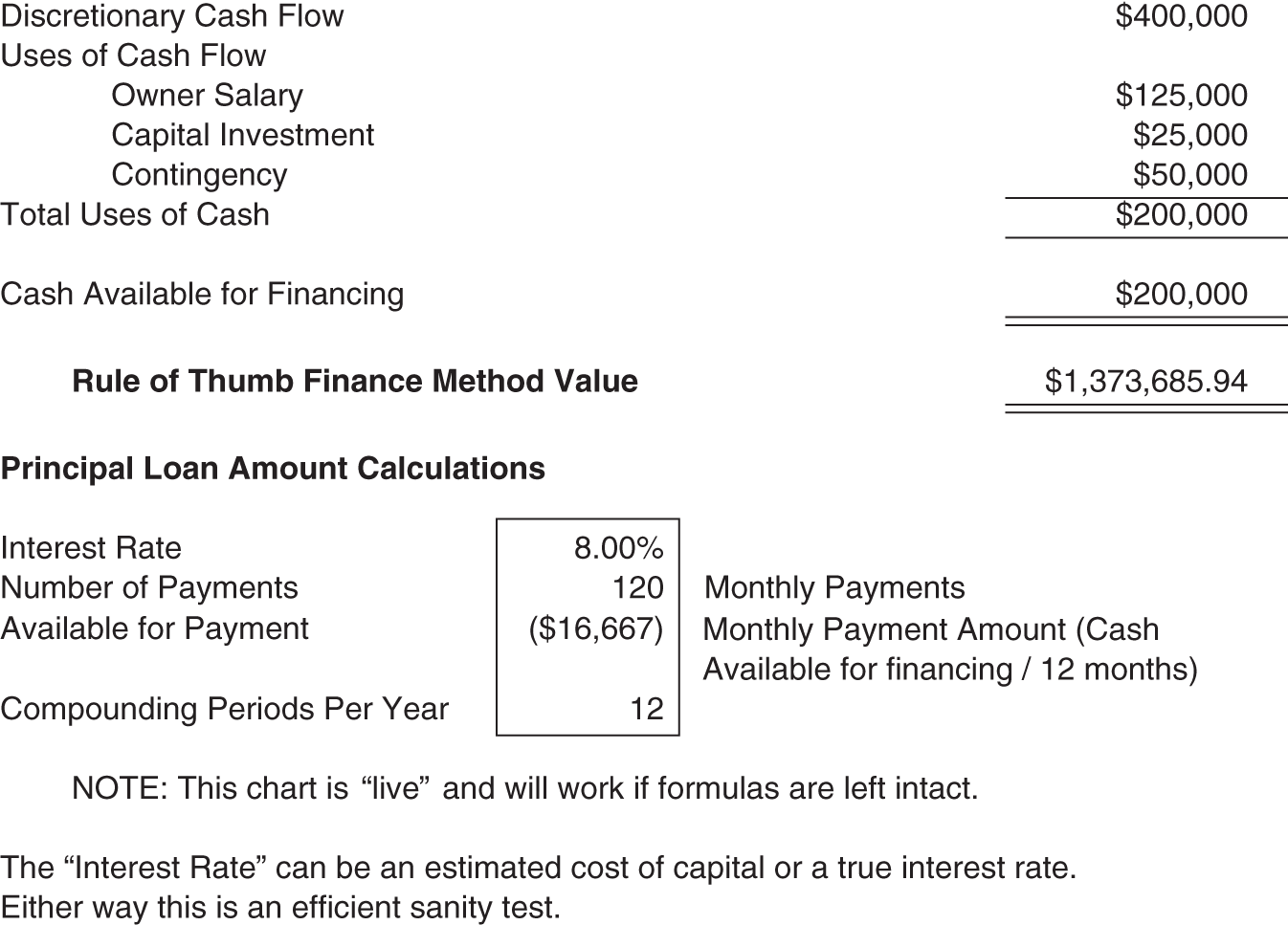

The capitalization of earnings method is a shortcut to the discounted cash flow method. Past financial information is used to estimate a cash flow for the next period that is then divided by a capitalization rate. The capitalization rate is a discount rate that is further adjusted to incorporate a growth factor to reflect projected future growth. A calculation of cash flow, a calculation of the capitalization rate, and an estimate of value are shown below. Use Figure 8.3 as a map when reading the portions of the chapter on capitalization of earnings.

CAPITALIZATION OF EARNINGS METHOD

The capitalization of earnings method is a shorthand version of the discounted cash flow method.7 Growth is calculated as an adjustment to the discount rate. A discount rate with a growth rate adjustment is a capitalization rate. (Said another way, the capitalization rate = discount rate – growth rate.) This capitalization rate is estimated and applied to adjusted past cash flows to calculate the effect of future cash flow growth.

Steady historic and likely steady future cash flow growth is the best situation for this model. That is because the valuator must select one growth rate for the future. Yet most small businesses do not have steady cash flow growth. Many cyclical businesses have more of a roller-coaster cash flow effect than steady long-term growth. Therefore, weighting or averaging a longer time period (perhaps five historical years) to estimate the growth rate is often reviewed. The found average rate is rarely directly used. Instead a rate to perpetuity must be estimated from this data. Growth rate can have a huge impact on the value found.

For instance, the value of a company with $1,000,000 of after-tax cash flow next year with a 20% discount rate and no growth is a 20% capitalization rate. This could well be the case for a mature small business where cash flow is not even keeping up with the rate of inflation. If the same company has a 4% growth rate, then the capitalization rate (discount rate - growth rate) is 16%. Perhaps new management has recently demonstrated short-term growth which is believed likely to continue into the foreseeable future.

| Line No. | Determination of After-Tax Cash Flow | Historic Year 3 | Historic Year 2 | Historic Year 1 |

| 1 | Historic Adjusted Pretax Cash Flow | $609,900 | $609,900 | $609,900 |

| 2 | Weighting | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 3 | Weighted Average Cash Flow | $609,900 | ||

| 4 | ||||

| 5 | Deduct Average Depreciation/Amortization | $40,000 | ||

| 6 | Taxable Income | $569,900 | ||

| 7 | State Corporate Tax Rate | 8% | ||

| 8 | Estimated Tax | $45,592 | ||

| 9 | Subtotal | $524,308 | ||

| 10 | Estimated Federal Tax Rate | 21% | ||

| 11 | Estimated Federal Tax | $110,105 | ||

| 12 | Subtotal | $414,203 | ||

| 13 | Plus Depreciation/Amortization | $40,000 | ||

| 14 | Decrease (Increase) Working Capital | $0 | ||

| 15 | Decrease (Increase) Capital Expenditures | $0 | ||

| 16 | Decrease (Increase) Long-Term Debt | $0 | ||

| 17 | Selected After Tax Cash Flow | $454,203 | $454,203 | |

| 18 | ||||

| 19 | ||||

| 20 | Calculation of the Capitalization Rate | |||

| 21 | ||||

| 22 | Cost of Equity | |||

| 23 | ||||

| 24 | Risk-free Rate of Return | 3.0% | ||

| 25 | Common Stock Equity Risk Premium | 6.0% | ||

| 26 | Small Stock Risk Premium | 5.4% | ||

| 27 | Industry Risk Premium | 3.7% | ||

| 28 | Company Specific Premium | 0.0% | ||

| 29 | Total Cost of Equity | 18.1% | ||

| 30 | Less Sustainable Growth | 3.0% | ||

| 31 | Next Year Capitalization Rate | 15.1% | ||

| 32 | Current Year Capitalization Rate | 14.7% | ||

| 33 | ||||

| 34 | Selected Capitalization Rate | 14.7% | 14.7% | |

| 35 | ||||

| 36 | Estimated Value Capitalization of Earnings | $3,089,818.50 |

Notes:

This Chart will be broken down and explained in detail.

Line No.

1 Historic Adjusted Pretax Cash flow is used.

Normalization adjustments will be made similar to those shown for the market method.

Weighting is performed similar to weighting in the market method.

5 Average depreciation/amortization is subtracted from the cash flow before taxes are adjusted.

32 Current Year Capitalization Rate - The analyst can either increase the cash flow to reflect next year's

after growth earnings (Current Year earnings times 1 + long-term growth) or adjust the capitalization rate

for the same amount. Namely take next year's capitalization rate and divide it by (1 + long-term growth)

Per the Gordon Growth model theory the immediate next period's cash flow is applied against the capitalization rate.

36 Line 17/line 34

FIGURE 8.3 Complete Capitalization of Earnings Calculation

The difference in value found is $5,000,000 at 20% and $6,250,000 at 16%.8 This shows the importance of estimating the growth rate correctly.

The underlying theory of the capitalization of earnings method is the Gordon Growth model or dividend discount model (DDM) as further explained in the next section.

The Gordon Growth Model

Variations of the Gordon Growth model are used to estimate a value of the future earnings stream of a company. It is the basis of many calculations in the income methods. It is the direct basis for the capitalization of earnings model and in estimating terminal value under the discounted cash flow model. A brief explanation follows.

The Gordon Growth model, also known as the dividend discount model (DDM), calculates the intrinsic value of a company's stock price. The stock value is calculated as the present value of all of the stocks' future dividends.

Generalizing this to fit all business sales, the formula becomes

For small businesses usually (but not always) instead of the dividend or distribution amount being used, the theoretical amount available for distribution (the distributable amount) is used. This figure is usually either EBITDA or EBIT or after-tax cash flow (essentially after-tax earnings plus depreciation and amortization) or somewhat improperly SDE.

This raises the issue of: how is reinvestment reflected in the model? The model assumes all reinvestment is at the perpetuity rate. In reality, as money is distributed, it often is spent or placed in safer investments that do not produce the same rate. This is an issue with the model as all models have problems. Again, professional judgment involves selecting the most useful models for our situation.

The Gordon Growth model accounts for the value of free cash flows that continue growing at an assumed constant rate in perpetuity.

Also, the projected free cash flow in the first year beyond the historic data (N+1) is used. This value is divided by the discount rate minus the assumed perpetuity growth rate:

- T0 Value of future cash flows (Price)

- D0 Cash flows estimated for the next period of time

- k Discount rate

- g Growth rate

See

- The cash flow (CF) for the year after the historic data is adjusted to grow at the estimated growth rate.

- The discount rate for the last year of the discrete cash flows then has the growth rate subtracted from it to estimate the capitalization rate.

- CF is then divided by the capitalization rate to find the value in perpetuity

Using this formula as the basis for estimating a value requires determining a cash flow, a discount rate, and a growth rate. Details on these matters and determining forecast cash flows and related issues under the income method are covered in the rest of this chapter.

MORE CASH FLOW CONSIDERATIONS

As suggested above, the first step is to normalize cash flows usually to either a seller's discretionary earnings (SDE), or earnings before interest and taxes (EBIT), or earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization (EBITDA), or the after-tax cash flow standard. Usually EBITDA or the after-tax cash flow is assumed to be distributable cash flow to investors or the equivalent for small business purposes.

Normalization adjustments to the cash flow will be made similar to those covered in Chapter 5, Normalization of the Cash Flows and Chapter 11, Accounting Issues with Small and Very Small Businesses.

Tax Affecting

In theory, buildup methods use after-tax cash flows because they are based on public companies which post after-tax earnings. When valuing a pass-through entity, valuators “tax affect” or make tax rate-based adjustments to maintain an equivalent cash flow basis (taxable to taxable) for the comparison.

Therefore, most valuators tax affect when using the income method to value very small tax pass-through entities.9 They believe it is the best alignment of the subject company to comparable data. Many small businesses are pass-through entities avoiding the double taxation of C corporations. These pass-through entities historically had a lower total tax to the investor at the investor level than non-pass-through entities. There is some level of debate about the true extent of this pass-through tax advantage, particularly with the passage of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA). Even prior to the TCJA, the tax rate of public entities in different industries was rarely the posted 35% average rate stated for companies with $10 million and above of taxable income.

TCJA may have solved most of the big differences in taxes to the shareholder between C corporations and pass-through entities at the Federal level but in high tax states, there still appears to be advantages for pass-through entities (PTEs) overall. Finally, it is still unclear what Code Section 199A Qualified Business Income Deduction (QBI) really means in the application for taxation of pass-through entity owners.10 More important, since it can depend on other income streams to the owner, how can we really make valid determinations as to what a buyer's tax benefits will be in our estimates?

There is a great debate on these topics at the time of writing of this book. It is beyond this book to go down every rabbit hole. Instead a reasonable methodology for use with small and very small businesses is going to be provided. Certainly, other methodologies may be used and there will be cases where this methodology is inappropriate but this should serve as a guide to work through these issues.

Factors to consider:

- Is this a valuation for the Internal Revenue Service (IRS)?

- Is the valuation standard fair value, investment value, or fair market value?

- Should state taxes be considered and deducted before the IRS rate?

- Do we have a reasonably reliable disposition date of the interests being valued?

IRS

The Tax Court has consistently found that when using the fair market value standard for PTEs, the cash flows should not be tax affected.11 However, two recent cases have to give the IRS pause. These are the Estate of Aaron Jones12 and Kress vs. United States.13 The IRS lost in both of these cases. What we don't know as of the writing of this book is if the IRS will acquiesce (i.e., accept them as law) with them or not. From a practical perspective it is unclear how the IRS will respond.

The historic IRS position has been that the future taxes of a hypothetical buyer are unknown. They cannot be known because different buyers will have different internal tax consequences depending on state taxes, loss carryforwards, whether the entity will remain private or become part of a public entity, etc. While this fails to deal with the issue of using two different income streams on different sides of the valuation equation, when valuing PTEs, it has been the IRS and Tax Court position at least until the Estate of Aaron Jones14 case. For this reason, many advisors take heed to this and use non-tax-adjusted cash flows for estate or gift tax type purposes.15

Issues with Tax Affecting

Similar to past IRS arguments, under fair market value, it is hard to know exactly what a buyer's tax status will be and if tax benefits of the seller will accrue to a buyer.16 This is made even more complex under the TCJA where a 20% qualified business income (QBI) deduction may be applied to a pass-through taxed business in certain industries that meet other income/wage limitations of the company and shareholders.

Qualification for these tax benefits are so complex as to almost be beyond many small and very small business tax advisors' ability to estimate future taxes, much less our ability as valuators to fully comprehend or adjust.

Below are some problems, not with the concept of tax adjusting, which conceptually is an easy “yes” we should, but by how much to adjust.

- When might the tax rates be changed again?

- The normalization process for calculating EBIT, EBITDA, and after-tax cash flows changes the tax status of many owner benefits. Namely, they were expenses by the company and in some cases not recognized by the beneficiary, i.e., some auto expenses. After being recast, they are now taxed. This can be a substantial portion of small business cash flows in some situations.

- The interaction of 199A of the tax code with pass-through entities is still being digested by the tax community, making it difficult to compare. With this provision it may always be difficult to create cross-industry models. In fact, some buyers may lose QBI deductions for buying certain types of businesses. (For instance, investment banking and valuation have often been performed by the same companies. Investment banking qualifies for QBI but business valuation does not and could theoretically cause a disqualification for the overall entity.)

- The 199A provisions sunset end of 2025 meaning the value of the tax benefit drops every year.

- These results under TCJA may also vary with the income of the owner and possibly the spouse, if married and filing joint taxes. This is a much more pertinent issue with very small businesses. How do we know or account for that?

- Strictly for very small businesses: The inability to amortize the purchase price of C corporations that tend to be stock sales raises the cash flow necessary to successfully buy a business. This is a barrier to sale. Most very small business sales are leveraged buy-outs using SBA loans. If the purchase price cannot be amortized, all of the principal payments have to be “after-tax” dollars. While a 10-year loan does not line up perfectly with 15-year amortization, it does make a big difference. (Plot the cash flows yourself.) This can be a 15% +/- “penalty” or gross up in terms of earnings required to really make the payments.

- In some cases, this is offset by personal goodwill. But there is still likely to be a large portion of un-amortizable corporate purchase price. Fortunately with small and very small businesses, personal goodwill does tend to exist.

- Most industries do not pay the “stated” tax rate. How do we really know (or how can we calculate) the tax rate being paid in the underlying public company data? Industry adjustment in the buildup methods is related to beta. Does that really mean we now have an implied industry tax rate in the buildup data?

- High state taxes vs. low state taxes can swing the analysis. Does the fact that the cash flow in Idaho with a 7.4% C corporation tax or Wyoming,17 the state next door with no corporate income tax, mean pretax earnings are really worth 6–8% more than the adjacent state? How is that passed through in value? How would we prove it even if it is true?

- According to Nancy Fannon,18 an expert on business valuation and taxation, research indicates that because a portion of the public company investor earnings stream is long-term capital gains and because much of the dividend-issuing stock is owned by investment companies that have different tax rates than individuals, the estimated implied tax rate on stock appreciation is 9% not the 20% capital gains rate. (I assume plus state taxes for high income earners.) Yet another big swing that an analyst may or may not agree with but could be difficult to explain.

- Daniel R. Van Fleet, ASA, another noted expert on taxation and business valuation, concludes because of TCJA, “that there are now three distinct types of business entities from a tax perspective: (1) C corps, (2) PTE service businesses, and (3) PTE nonservice businesses.” He further concludes that C corps experienced the greatest increase in value, non-service PTEs continue to have benefits above C corps, but service PTEs' benefits have largely disappeared19 as compared to C corporations.

- Using a tax effect calculator, the results vary dramatically with many plausible situations. How do we account for that? See Figure 8.5 on p. 174.

Something that is clear compared to larger companies:

- One thing that does simplify the analysis is that most small and very small companies are either purchased by pass-through entities or the buyer forms a new pass-through entity. It is very rare for a small or very small business to be purchased by a C corp. Therefore, the cash flows and perhaps tax benefits of buyers are likely to be similar to sellers. (Again, beware of service vs. non-service PTEs if that can be determined.)

- Prior to the TCJA, a study of data from Pratt's Stats (at the time, only small private company data was represented) found evidence of a PTE premium WHEN the buyer can take advantage of the pass-through benefits. This premium was estimated to be in the 15–24% range using varying methodologies.20

Some analysts may have clear answers to many of the above questions. Much of it does not appear to be knowable. Therefore, apply reason. Another situation for asking yourself: “Does this make sense?”

Suggested Tax Affecting Method for Small and Very Small Businesses

Based on the situation today, below may be one methodology to use. It is logical and supportable assuming a typical fact pattern. This area is in flux and lacks agreement. Use tax affecting or not according to your best judgment.

The first step is to tax affect the cash flows to the estimated corporate rate:

- Tax affect the found normalized cash flows.

- For guidance to the tax affect amount, assuming you are using an industry adjustment, look at the IRS statistics on corporate taxes by sector.

- Tax affect for the state tax rate. Again, most small businesses' income stream is often derived from one state. If it is derived from multiple states, a composite rate may be used. The first step is to tax affect the cash flows to the estimated corporate rate:21

An example of tax affecting to the corporate rate is shown in Figure 8.4.

| Weighted Average Cash Flow | $500,000 |

| Deduct Average Depreciation/Amortization | $40,000 |

| Taxable Income | $460,000 |

| State Corporate Tax Rate | 8% |

| Estimated Tax | $36,800 |

| Subtotal | $423,200 |

| Estimated Federal Tax Rate | 21% |

| Estimated Federal Tax | $88,872 |

| Subtotal | $334,328 |

| Plus Depreciation/Amortization | $40,000 |

| After Tax Cash Flow | $374,328 |

| Note: This estimate is before adjusting for working capital, long-term loans and capital investment | |

FIGURE 8.4 Tax Affecting for Capitalization of Earnings

- More details to think about when applying the above suggested adjustment are shown in https://www.treasury.gov/resource-center/tax-policy/tax-analysis/Documents/Average-Effective-Tax-Rates-2016.pdf

- Here is average tax rates for individuals prior to TCJA: https://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-soi/14insprbultaxrateshares.pdf

- If they are not available or do not appear reasonable for your industry, use 21% for the corporate rate.22

- State taxes can be difficult, as they vary. (Forty-four states levy a corporate income tax from 2.5% in North Carolina to 12% in Iowa. Four states have a gross receipts tax instead of an income tax. Two states have no corporate income tax or gross receipts tax.)23 Small and very small businesses tend to be in one state and pay that state's tax. In addition, some larger cities have their own taxes so if that is material, they should be added. If multiple state taxes are paid, use a figure based on a reasonable weighting as most taxes are based on profits derived from earnings in the state.24

- This should provide a reasonable adjustment to account for the corporate tax rate used in the buildup methods. Now the valuator must still adjust for differences between the buildup tax level and the pass-through entity tax level.

Adjust the discount rate or capitalization rate for the pass-through tax benefit (if any)

- Use the tax affect calculator below to develop a sense or range of options.

- Understand if the PTE is a service or non-service entity. This may require a detailed look-up. Many of the broad titles are misleading. For instance, it is widely stated that brokerage is under the service category. But real estate brokerage and business brokerage count as non-service. Architecture and engineering are in non-service but accounting is service.

- Non-service entities are likely to justify a reduction in discount or capitalization rate by 2% or 3% (example: 16% – 2% tax benefit = 14% cost of capital), a range based on Van Fleet's and Eric Barr and Peter L. Lohrey's findings.

- Use common sense and judgment.

- For small and very small businesses this may be like trying to perform surgery with a hatchet.

I find this simpler than trying to create a comprehensive formula. We are simply creating apples to apples with the cash flows, then adjusting for assumed advantages due to tax treatments where it appears they exist. This should also be much easier to explain to less sophisticated users and produce a reasonable result.

Use a tax affect calculator, such as the one in Figure 8.5, to approximately estimate the difference in after-tax cash flows between public C corporations and pass-through entities. Be sure to factor in both state and Federal taxes. In addition, remember the research that indicates a 9% paid tax rate on distributed cash flows from the public company earnings.25 Use this with various scenarios to develop a sense of how your situation may play out. (A functional Excel file is on the related website.) Two scenarios are shown using a very simple tax affect converter table in Figure 8.5. Then use your best judgment.

| C Corp | S Corp | |

| Income Before Corporate Tax | $100 | $100 |

| Corporate Tax Rate (State and Federal) | 29.00% | 0.00% |

| Available Earnings | $71 | $100 |

| Taxes At Personal Level | 28.00% | 43.00% |

| After Personal Level Tax Earnings | $51 | $57 |

| Premium per S Corp Model | 11.50% | |

| Assumed 21 % Federal Corporate Tax Rate plus 8% State | ||

| Assumed 20% Capital Gains plus 8% State | ||

| Assumed 35% individual plus 8% State | ||

Notes:

*If research cited by Nancy Fannon is believed and the 28% C Corp personal tax is replaced with 9%, then there would be a -12% rounded premium.

*If the 9% is then plus the 8% State Tax, the premium is - 3%.

FIGURE 8.5 Tax Affect Converter Table

This analysis may change as the current law is better understood, technology allows better tax estimates, and the tax law changes.

Adjusting Cash Flows for Working Capital, Capital Expenditures, and Debt under Capitalization of Earnings

The theory behind the income methods is that we are calculating the distributed cash flow to owners adjusted to compare to a public company and therefore after-tax data. In practice, particularly with the capitalization of earnings method for small businesses, distributable after-tax cash flow is often used. This can be justified because the undistributed cash flow is usually used in the business for expansion. This expansion, assuming it is profitable, increases future earnings power and often produces a higher growth rate than when the company distributes frequently. Remember, small and very small businesses have much less access to affordable capital. Because of their volatility, debt is often much more risky for them. So, retaining a portion of the distributable capital is usually neutral to a positive.

In some cases, if the cash needs during growth are high for two or three years, then phase out, it may be worth preparing a rough forecast as opposed to “jamming” that situation into the capitalization of earnings model. Again, this model works best with fairly consistent cash flows into the future.

Yet, in some circumstances, the best application of the model does include further adjustments to the distributable cash flow. These adjustments fall under the categories: increase or decrease in working capital, capital investment, and debt.

Because the method can only adjust all future cash flows (there is not a mechanism to change the cash flow year by year), the best that can be done when these factors are present is to estimate the current amount and then reasonably adjust the amount to a figure reasonable for use in perpetuity. This requires recognizing that early money and cash flow are much more valuable than later money. Because of the time value of money and the assumption of declining growth rates over time at typical capitalization rates for small and very small businesses, after about 40 years the present value contribution of earnings is near 0. See Figure 8.6.

Therefore, one factor in determining these adjustments for cash flow is how long the use of cash is likely to continue. Principal to pay off a new 10-year note might be shown at 50%, as it is to be allocated out over a reasonably long time early in the life of the projection. Perhaps a few larger mid-term equipment purchases would be allocated at 10% of the payment figure, if they are going to be reduced significantly after two or three years. Of course, if reinvestment is continuous, then the whole amount might be deducted from the cash flow. Again, this is an area for judgment and the capitalization of earnings model is used in these situations on a “best we can do” basis (Figure 8.7).

| Annual Cash Flow Amount | $100,000 | ||||||||

| Capitalization Rate | |||||||||

| Period | 10.00% | 15.00% | 20.00% | 25.00% | 30.00% | 35.00% | 40.00% | 45.00% | 50.00% |

| 1 | $90,909 | $86,957 | $83,333 | $80,000 | $76,923 | $74,074 | $71,429 | $68,966 | $66,667 |

| 2 | $82,645 | $75,614 | $69,444 | $64,000 | $59,172 | $54,870 | $51,020 | $47,562 | $44,444 |

| 3 | $75,131 | $65,752 | $57,870 | $51,200 | $45,517 | $40,644 | $36,443 | $32,802 | $29,630 |

| 4 | $68,301 | $57,175 | $48,225 | $40,960 | $35,013 | $30,107 | $26,031 | $22,622 | $19,753 |

| 5 | $62,092 | $49,718 | $40,188 | $32,768 | $26,933 | $22,301 | $18,593 | $15,601 | $13,169 |

| 6 | $56,447 | $43,233 | $33,490 | $26,214 | $20,718 | $16,520 | $13,281 | $10,759 | $8,779 |

| 7 | $51,316 | $37,594 | $27,908 | $20,972 | $15,937 | $12,237 | $9,486 | $7,420 | $5,853 |

| 8 | $46,651 | $32,690 | $23,257 | $16,777 | $12,259 | $9,064 | $6,776 | $5,117 | $3,902 |

| 9 | $42,410 | $28,426 | $19,381 | $13,422 | $9,430 | $6,714 | $4,840 | $3,529 | $2,601 |

| 10 | $38,554 | $24,718 | $16,151 | $10,737 | $7,254 | $4,974 | $3,457 | $2,434 | $1,734 |

| 11 | $35,049 | $21,494 | $13,459 | $8,590 | $5,580 | $3,684 | $2,469 | $1,679 | $1,156 |

| 12 | $31,863 | $18,691 | $11,216 | $6,872 | $4,292 | $2,729 | $1,764 | $1,158 | $771 |

| 13 | $28,966 | $16,253 | $9,346 | $5,498 | $3,302 | $2,021 | $1,260 | $798 | $514 |

| 14 | $26,333 | $14,133 | $7,789 | $4,398 | $2,540 | $1,497 | $900 | $551 | $343 |

| 15 | $23,939 | $12,289 | $6,491 | $3,518 | $1,954 | $1,109 | $643 | $380 | $228 |

| 16 | $21,763 | $10,686 | $5,409 | $2,815 | $1,503 | $822 | $459 | $262 | $152 |

| 17 | $19,784 | $9,293 | $4,507 | $2,252 | $1,156 | $609 | $328 | $181 | $101 |

| 18 | $17,986 | $8,081 | $3,756 | $1,801 | $889 | $451 | $234 | $125 | $68 |

| 19 | $16,351 | $7,027 | $3,130 | $1,441 | $684 | $334 | $167 | $86 | $45 |

| 20 | $14,864 | $6,110 | $2,608 | $1,153 | $526 | $247 | $120 | $59 | $30 |

| 21 | $13,513 | $5,313 | $2,174 | $922 | $405 | $183 | $85 | $41 | $20 |

| 22 | $12,285 | $4,620 | $1,811 | $738 | $311 | $136 | $61 | $28 | $13 |

| 23 | $11,168 | $4,017 | $1,509 | $590 | $239 | $101 | $44 | $19 | $9 |

| 24 | $10,153 | $3,493 | $1,258 | $472 | $184 | $74 | $31 | $13 | $6 |

| 25 | $9,230 | $3,038 | $1,048 | $378 | $142 | $55 | $22 | $9 | $4 |

| 26 | $8,391 | $2,642 | $874 | $302 | $109 | $41 | $16 | $6 | $3 |

| 27 | $7,628 | $2,297 | $728 | $242 | $84 | $30 | $11 | $4 | $2 |

| 28 | $6,934 | $1,997 | $607 | $193 | $65 | $22 | $8 | $3 | $1 |

| 29 | $6,304 | $1,737 | $506 | $155 | $50 | $17 | $6 | $2 | $1 |

| 30 | $5,731 | $1,510 | $421 | $124 | $38 | $12 | $4 | $1 | $1 |

| 31 | $5,210 | $1,313 | $351 | $99 | $29 | $9 | $3 | $1 | $0 |

| 32 | $4,736 | $1,142 | $293 | $79 | $23 | $7 | $2 | $1 | $0 |

| 33 | $4,306 | $993 | $244 | $63 | $17 | $5 | $2 | $0 | $0 |

| 34 | $3,914 | $864 | $203 | $51 | $13 | $4 | $1 | $0 | $0 |

| 35 | $3,558 | $751 | $169 | $41 | $10 | $3 | $1 | $0 | $0 |

| 36 | $3,235 | $653 | $141 | $32 | $8 | $2 | $1 | $0 | $0 |

| 37 | $2,941 | $568 | $118 | $26 | $6 | $2 | $0 | $0 | $0 |

| 38 | $2,673 | $494 | $98 | $21 | $5 | $1 | $0 | $0 | $0 |

| 39 | $2,430 | $429 | $82 | $17 | $4 | $1 | $0 | $0 | $0 |

| 40 | $2,209 | $373 | $68 | $13 | $3 | $1 | $0 | $0 | $0 |

FIGURE 8.6 Present Value Contribution over 40 Years

Increase or Decrease in Working Capital

A simple and usually sufficient formula for estimating working capital is provided in the balance sheet adjustments section in Chapter 11, Accounting Issues with Small and Very Small Businesses. If additional (or less) working capital is going to be required in the future, the question becomes how much working capital change is really required to tie into the assumption of perpetual growth at a fairly low but persistent rate. That figure can be tied to a rate of revenue growth and adjusted for perpetuity.

| Historic | Historic | Historic | ||

| Line No. | Determination of After-Tax Cash Flow | Year 3 | Year 2 | Year 1 |

| 1 | Historic Adjusted Pretax Cash Flow | $609,900 | $609,900 | $609,900 |

| 2 | Weighting | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 3 | Weighted Average Cash Flow | $609,900 | ||

| 4 | ||||

| 5 | Deduct Average Depreciation/Amortization | $40,000 | ||

| 6 | Taxable Income | $569,900 | ||

| 7 | State Corporate Tax Rate | 8% | ||

| 8 | Estimated Tax | $45,592 | ||

| 9 | Subtotal | $524,308 | ||

| 10 | Estimated Federal Taxe Rate | 21% | ||

| 11 | Estimated Federal Tax | $110,105 | ||

| 12 | Subtotal | $414,203 | ||

| 13 | Plus Depreciation/Amortization | $40,000 | ||

| 14 | Decrease (Increase) Working Capital | ($30,000) | ||

| 15 | Decrease (Increase) Capital Expenditures | $10,000 | ||

| 16 | Decrease (Increase) Long Term Debt | $0 | ||

| 17 | Selected After Tax Cash Flow | $434,203 | ||

| 18 |

Notes:

This Chart will be broken down and explained in detail.

Line No.

1. Historic Adjusted Pretax Cash Flow is adjusted pretax profits plus depreciation and amortization.

5. Average depreciaion/amortization is subtracted from hte cash flow before taxes are adjusted.

7. Estimated State Corporate Taxes.

10. Estimated Federal Corporate Taxes.

13. Depreciation and amortization is added back to cash flow.

14. Adjustment to Working Capital. Remember this is for each year to perpetuity, not next year.

15. Adjustment to Capital Expenditures each year to perpetuity.

16. Long-Term Debt adjustment each year to perpetuity.

FIGURE 8.7 Estimating the Cash Flows for Capitalization of Earnings

Finally, if the balance sheet shows excess assets on the valuation date, including excess working capital, this should be added to the final value found.

Capital Investment or Cap X

Some industries require constant capital investment in order to grow or even maintain operations. Trucking, excavation, some manufacturing lines that wear out equipment, and the like. Most small and very small businesses are using computer-based technology to enhance productivity and certainly many industrial machines have computer enhancements. But the cost and complexity of large-scale automated equipment have prevented large-scale implementation in small and very small businesses. Therefore, generally, most small and very small businesses, even in manufacturing, tend to do repairs, refurbishing, or assembly as opposed to heavy manufacturing. These businesses, similar to service providers, tend to have lesser capital investment compared to revenues and other cash flows.

If capital investment is a material factor and a requirement for the company's cash flow to continue, then it should be estimated and put into the cash flow calculation. Note that depreciation, whether accelerated or not, is often not a reasonable assumption for long-term capital investment in most cases. Some businesses have major investments from time to time. These are not always predictable. Estimating the timing of these investments may be difficult.

Increases and Decreases of Debt

Debt can be used for growth capital or to get “cash out” of an investment. If the debt is undertaken with the intent to get cash out of an investment, the discounted cash flow method will be superior, as this is almost always a one-time event, at least in the foreseeable future.

When a company carries material amounts of debt, it is important to align the cash flows with the discount/capitalization rate. Cash flow to equity (after the payment of all debt in the capital structure) can vary dramatically from cash flow to total invested capital. This is magnified by the fact that these are cash flows to perpetuity.

Most small businesses do not carry significant debt indefinitely into the future. When they do, it is often in the form of lines of credit against invoices or inventory, or equipment debt where the equipment is regularly replaced. Some small and very small companies do carry receivables lines and while they are short-term debt in name, the small companies often treat the line as long-term debt. These callable lines are not reduced but a long-term feature of the capital structure and should be treated as long-term debt.

Long-term debt may also be handled by not adjusting the cash flow (assuming EBITDA cash flow is being used) and reducing the value found by the debt similar to the treatment under the market method. This is often a reasonable treatment if the purpose is to determine equity value in a sale. In instances where the standard is more a value to the holder and the debt is continuing, a cash flow adjustment for principal payments may be the best solution to address the debt. Note these variations in treatment can result in large fluctuations in value if not performed thoughtfully.

Next we will review estimating cash flows under the discounted cash flow method. If you wish to continue reviewing the capitalization of earnings method, skip down to “Calculating a Discount or Cap. Rate”.

CASH FLOW FORECASTS UNDER THE DISCOUNTED CASH FLOW METHOD

Forecasts are used to estimate the cash flows in the discounted cash flow method. Therefore, we will start by reviewing forecasts, then estimating the present value discount, and finally showing how to estimate the terminal year calculations.

The first step, review and analysis of the forecast itself, is often skipped by valuators. And no wonder, this is where the most common sense and professional judgment are required. With smaller businesses, often the forecasts do not make sense. With larger businesses, the forecasts can become so complex that even when the analyst has a strong opinion as to the reliability or likelihood of reaching the projected result, the issue becomes (due to complexity) how can an analyst make the changes?26

Fortunately with smaller companies, if there are forecasts, it is easier to apply some common sense to check reasonableness. Remember, the forecast is unlikely to be correct with the addition of hindsight. Valuators can only work with the information in hand as of the valuation date, if it is reasonable, to ensure accuracy and supportability based on assumptions and data.

In most cases, do not build the forecast yourself. That can be criticized as valuing your own work. Have management prepare the forecast. Yet there are circumstances where a simplified and clearly explained forecast generated by the valuator may be the best that can be provided.

Review of Forecasts

Below is a checklist that should be used to review projections and forecasts. Clearly the more complex the company and the forecast, the more time and attention that will need to be applied.

- Look at historic data: three to five years.

- Understand revenue, expense, and profit trends.

- Understand management structure and product or services.

- Look for bottlenecks and weaknesses in the soft side of business that could improve or worsen financial results.

- Has something changed significantly with management, products, production, etc. (for instance, a transportation company went from using their own trucks to subcontracted trucks) during the historic period or going into the projection period?

- If the business is a start-up or if major changes are projected from the past, review all assumptions and the facts or basis for those assumptions.

- What is the support for the changes?

- Carefully review the future forecasts.

- Who prepared the forecast?

- Why was the forecast created?

- What date was it created?

- Where did the key facts and assumptions come from?

- If based on contracts or other existing back-up, can you review the back-up?

- Is there a history of forecasts?

- If so, compare forecasts vs. results. Are they reasonably consistent or is the variance consistent?

- Overall forecast review

- Does it reasonably transition from historic data to forecast?

- If there is a “hockey stick” effect, do the assumptions and facts and other support make sense? Unfortunately there often is an unsupportable jump or a jump that happens far faster than is likely to do so in real implementation. (Due to the time value of money moving up cash flows a year in the early years can greatly swing value.)

- Harder to evaluate is a growth rate which is reasonable in one year but not over many years.

- High growth over five or ten years is difficult for most companies even if the rate is reasonable for one or two years.

- Detailed forecast review. Look at cost of goods sold (COGS) and gross margins, expenses, and profits.

- If gross margins and profits are increasing, is the increase supportable?

- If gross margins and profits are falling, where does growth become unprofitable or unsupportable by cash flow or borrowing ability?

- Where are breakpoints for the fixed costs, such as rent?

- Are there other major capital investments required?

- If so, what are the volume or dollar break points?

- Are those being adequately addressed?

- Again, with long-term growth, can the soft side expenses such as the management team appropriately expand?

- A $10 million revenue company may get by with a controller-level person but a $20 million revenue company might need both a controller and a true CFO. Is this addressed?

- Many small businesses are primarily labor or skilled labor providers (including many “service” businesses) or perform light assembly with similar types of people. Management is critical particularly if work is performed in multiple, possibly changing, locations.

- What is the timing of and what is a realistic rate for adding quality managers and skilled employees?

- This is often the true limiting factor and too often overlooked.

- What systems, training, and checks are in place to manage the managers as necessary?

- Many fast-growing service companies in cyclical businesses lose control of work quality and profitability in spurts of growth. Often this shows up in lower margins and warranty costs a year or two later. An example, a demolition contractor tore out two office bathrooms in an office building so they could be remodeled. Only they were on the wrong floor. A very expensive mistake due to quick recent growth and inexperienced middle management. This is not as unusual as you may think.

- What is the timing of and what is a realistic rate for adding quality managers and skilled employees?

- While a generality, for smaller companies, less professional-looking forecasts prepared by the owner or key manager often are more likely to be supportable than fancy forecasts prepared by financial consultants who better understand how to “make the numbers look right” and sometimes use industry standard numbers that poorly tie into past financials.

- Often valuation-adjusting entries will need to be made to the forecast. Document your work.

- Write down all questions and concerns.

- If possible, have a conversation with the person who produced the forecast to make sure you fully understand assumptions, calculations, and the like.

- Review with the owner or appropriate manager (or both) all your questions.

- “Why” is a powerful question. Ask “why” and “how” often. Ask “why” three times in a row. You will be amazed at what you learn.

- If you cannot have a direct conversation, get questions answered via email.

- Take notes and think about what was said. Write down key thoughts on why it works and/or why it does not work. Review Chapter 13, Assisting the Small Business Buyer or Seller, the section on How to Ask Questions Effectively.

- If the forecast is simple and needs adjustment in some circumstances, the analyst might make the adjustments. Be sure to document the assumptions and adjustments. You likely will want to show the original and the adjusted version in the report.

- If the forecast is complex, adjust either the discount rate (if using very long holding periods) or a likelihood adjustment prior to calculating a discount.

- At some point, the forecast may not be meaningful enough to use at all. This is quite common with small and very small businesses.

Once the forecast is understood, then adjustments need to be made to develop the cash flow that is going to be used in the discounted cash flow calculation.

Often EBITDA or after-tax cash flow is used to show cash flow for small businesses. Because, in theory, this is return to investors (in practice with small businesses, it tends to be potential return to investors), some decisions need to be made to determine what investors could receive. These areas include necessary increases or decreases in working capital, necessary capital investments, and obtaining additional credit and/or paying credit.

If the forecast is well built, it will include these factors. Yet, with small businesses, balance sheets are usually not provided (maybe never provided) and matters related to balance sheets are not considered. Therefore, the valuator may need to add them or, at a minimum, check if it is reasonable that the business could expand at the projected rate with the internal cash flow for working capital and capital investment.

Forecasts and Balance Sheet Accounts

Because balance sheets and other financial checks are often missing, important limitations on growth, or restrictions on distributions while growth is occurring, may be missed.

If possible, a balance sheet should be prepared each year as part of the annual forecasts. Since that possibility is unlikely with small and very small companies, the analyst should perform some level of analysis and, if necessary, make adjustments to the forecast or the discount or cap. rate when necessary. These should be factored into the forecasts each year in the discounted cash flow method.

Working Capital

In many industries where the small company is providing materials or labor to large companies, the subject company will be expected to extend short-term credit in the form of accounts receivable to their client base. The credit collection time term is often 45–60 days with some extending to 90 days. Many engineering firms, industrial manufacturers, construction subcontractors and the like can fall into this category.

Therefore, the first concern is, can the company generate enough cash to support growth? If not, what is a realistic growth rate or can the company borrow the cash, perhaps on a line secured by receivables? Just remember, receivables financing at reasonable rates tends to vanish in many industries during recessions.

A fairly detailed analysis on estimating working capital is shown in the “Working Capital” section of Chapter 11, Accounting Issues with Small and Very Small Businesses. If possible, adjust the forecast (even if a simplified model for your work papers) to understand the growth limits based on working capital needs.

Do finally note, excess assets, including excess working capital, on the balance sheet as of the valuation date should be added to the value found under this method.

Capital Expenditures

Certain industries require heavy capital equipment spending, e.g., excavation and some other construction trades, equipment rental companies, certain manufacturers, even distributors or retailers experiencing rapid growth. Rapid or high investment reduces otherwise distributable cash. With high levels of accelerated depreciation for small companies, a review of tax implications should also be performed if using an after-tax cash flow.

So carefully review the necessary level of capital investment to grow at the rates projected in the forecast. Is a proper cash flow set aside for these purposes? If not, adjust.

Increase or Decrease in Debt

Increasing debt provides cash to use for investment in working capital and capital goods. While somewhat rare with small and very small businesses, increasing debt can also provide cash for distributions.

Small company debt is likely to include personal guarantees, so the credit worthiness of the owner and potential collateral outside the business also may be factors that need to be reviewed, if valuing a high growth company. But, if increasing debt is a viable solution, make sure interest and, where applicable, principal payments are factored into the ongoing cash flows.

One issue with discounted cash flow models that is more pronounced with very short forecasting periods is the effect of working capital, capital investment, and debt that may not have properly stabilized when the forecast ends and the terminal value is calculated.

Generally, debt is not subtracted from the value found when using the discounted cash flow. With small businesses where debt tends to be called and required to be paid at conveyance (again, what is the purpose of the valuation?), there may be times when subtracting the debt from the value found is appropriate.

All valuators can do is use or adjust to reasonable forecasts. It will be very rare when they actually look like the future. But, they can be a reasonable model of a likely outcome.

CALCULATING A DISCOUNT RATE OR CAP. RATE

A discount rate will be estimated first. Additional steps necessary to estimate the capitalization rate will then be shown. All the steps and factors discussed when estimating a discount rate apply to the capitalization rate. In most cases the capitalization rate formula and the terminal value rate formula (before discounting to present value step) used in the discounted cash flow are similar.

The discount rate is the pricing method to determine how much an investor will pay for the cash flow of a business (or anything else such as a public share of stock, investment real estate, a debt, or perhaps a government bond) with the same level of risk as the subject company. Therefore, the valuation analyst must keep the following in mind:

- Investors are looking across all investment classes and types. It is the risk of this investment as compared to all other investment alternatives to as viewed by the market of investors. This is driven by the investment market. This is what creates value for investors, not the value to the current owners. (Most businesses do not sell or are not on the market because the value to the current owners is significantly higher than the value to investors or other potential owner-operators.)

- Risk of not making the projected cash flows is a primary determinant of the discount rate. As risk goes up, it drives down the value. Investment risk as defined for investors is the degree of uncertainty that future payments or earnings will be obtained.27 Note that this risk is the apparent risk, hence the need for judgment as there is no certainty.

Once the history, forecast, and subject company's strengths and weaknesses are understood, then a discount rate needs to be calculated. As in many other areas of business valuation, there used to be one, then two methods to calculate a discount rate, but now there are many.

Sources of Data for Discount and Capitalization Rates

The income method appears simple and when there only was the Ibbotson data available, it was. One needed to simply pull data from one page in a book and maybe look up the industry adjustment in another table that was maybe six pages long. It was simple to apply. Of course, very few people ever read the thick book where the one page was located.

The income method is often used by valuation professionals in litigation because of this apparent simplicity. This simplifies the understanding by a judge and jury and reduces the risk of cross-examination. In addition, since it is the most commonly used method, it clearly meets the judicial test of being a proven method.

The income method was never simple. Read the Valuation Handbook: Guide to Cost of Capital book by Duff & Phelps to begin to understand the complexities and assumptions made in the method. (This book can be downloaded, by chapter, from the Cost of Capital Navigator website at www.dpcostofcapital.com.) Another really curious issue that is rarely raised is the lack of clarity or connection between the history back to 1926 for the Center for Research in Security Prices (CRSP) data used in the Ibbotson calculations by Duff & Phelps and what that really tells us about tomorrow. Duff & Phelps' own methodology is calculated from 1963 onwards.

That being said, commonly used or referenced sources at the time of publication include:

- Duff & Phelps/Ibbotson (Duff & Phelps continue to publish the Ibbotson methodology)

- Duff & Phelps

- BV Data

- Aswath Damodaran

- Pepperdine Cost of Capital

Sources appear to be multiplying, so more likely do exist.

Duff & Phelps Products. Under Duff & Phelps model, a calculated risk-free rate is used to smooth out fluctuations that are thought to come from quantitative easing and other sources. Yet as time passes, low risk-free rates are looking more and more the norm.28 How does this really affect small and very small businesses? Certainly small and very small business interest rates have not dropped commensurate with large company rates. (The typical SBA rate at the date of writing in August, 2019 is prime at 5.25% plus 2.5% or 7.75% while Grade A Corporate bonds are at 3.21%.)29

Duff & Phelps calculate both the forward-looking and the backward-looking cost of capital figures. Again, valuation theory is forward-looking. Historic data is backward-looking, supply side is forward-looking. Forward looking requires more assumptions. Assumptions about the future vs. using the past (which is not the future, yet we rely on the past for trend analysis). We are looking to predict the near-term future. This is a constant tension in business valuation.

Duff & Phelps also calculate the buildup data using the same formulas as the Ibbotson data. This may be the most commonly used set of indicators as it has the advantage of long-term use and familiarity. This data includes the breakdown of Decile 10 which is very important for valuing small and very small businesses.

The Cost of Capital Navigator is a complex product. There are complaints of it being a “black box”; however, Duff & Phelps have now included supplementary data that clarifies how the results are estimated. Yet the buildup method was always this complex. At least now we can look at different components individually and intelligently select the components that most affect the subject company, and, using professional judgment, select the correct discount rate. This judgment will improve as valuators work with the product.

Duff & Phelps products (https://www.duffandphelps.com/learn/cost-of-capital) are still the most widely accepted and used for most cost of capital purposes.

Aswath Damodaran. He calculates forward-looking cost of capital data that is based on current financial market results.30 Dr. Damodaran tends to work with very large capitalization companies and therefore the data may not be as useful for small and very small companies. He also calculates and publishes industry beta information and debt to equity relationships. Very useful for the Cap-M buildup method and the weighted average cost of capital iteration. Every business valuator should visit his website, which has a humble appearance, but is filled with information (http://pages.stern.nyu.edu/∼adamodar/).

BV Resources. BV Resources' product, “Cost of Capital Pro” (https://www.bvresources.com/products/cost-of-capital-professional) allows valuators to select the start year for data instead of assuming 1926. It uses the CRSP data just as Duff & Phelps does. It does not break down Decile 10. This is unfortunate when valuing small and very small businesses as Decile 10 businesses (even the small end of them) are still huge compared to small and very small businesses. The product is claimed to be simpler and transparent but it is based on the CRSP data, which is quite complex when fully researched.

Different start dates produce radically different results. This leads to a host of questions that did not exist when valuators presumed one start date for all data. At this point there does not appear to be an answer to the questions of which year do we choose as a start date and why?

The BV data originally referred the valuator to the Damodaran Beta charts. They now have the charts as part of their tool. Again, these products are changing rapidly as adaptation from books to databases is opening up more options and ways to compare data. Overall, this is a very good product and has gained market share quite rapidly since its release.

Pepperdine Private Capital Markets Report. This is an unscientific survey of what investors and banks are requesting, which can be quite different from what they receive. (As many investors told me when I was raising capital, “We want 25–35% internal rate of return (IRR)31 on the forecast but if you really get us 12–15% over three to five years, we will invest again.” I will also note that statement was given at a time (1995) when there were much higher treasury bill rates.) The study is based on asking participants, such as owners, private equity groups, bankers, business brokers, investment bankers, and other groups questions about the cost of capital and the state of the sales and finance market.

The 2018 Pepperdine Survey also revealed that 48% of small and very small business owners think that their cost of equity is less than 10%. That is a very questionable assumption to assert, at least for third party money. For years, these reports were free, but now are available for purchase on Amazon. The Pepperdine Survey is a wonderful reasonableness/sanity test but use with caution.32

Partnership Profiles. Partnership Profiles' model33 is used to calculate a cost of capital for holding companies and family limited partnerships, particularly non-marketable minority interests. With the higher estate tax limits, valuations of these interests (particularly small and very small holdings) have become less common and will not be discussed in this book.34

There are other sources of discount rates for various valuations in specialized circumstances. These will rarely be encountered or necessary when valuing small and very small businesses.

COST OF CAPITAL BUILDUP METHOD (BUM): CALCULATING A DISCOUNT RATE

The basic premise is that data primarily from the public markets will be taken and used to estimate required investment returns at various levels of risk.

It has become common for valuators to take multiple sources of cost of capital data and compare the results from multiple data sources. Yet, most of the data is coming from the same underlying financial data. Therefore, it seems (but I certainly do not have proof) that using more than one source of discount rate data for a buildup just muddies the water. (We all know there are going to be variances but we have no knowledgeable basis for making a selection beyond “the best available data.”) Select the best data source and use it. Particularly with small and very small businesses, the cash flow issues and business risk far outweigh the improvement (if there is one) to weighting multiple sources in the selection of a rate.

Part of Duff & Phelps' Cost of Capital Navigator is the offshoot of the Ibbotson Cost of Capital series of books, Stocks, Bonds, Bills, and Inflation, used for years for cost of capital calculations. Duff & Phelps published the data for approximately five years. No other source breaks down Decile 10 data which comes closest to representing small and very small companies. For these reasons, examples in this book will work with data from Duff & Phelps.

One of the aims of this book is to simplify business valuation by focusing on what really matters to obtain as accurate a valuation as possible. With this in mind, I had the opportunity to ask Roger Grabowski how a valuator working with a small company should use the Navigator. His comment was: “Use the CRSP buildup data, namely, the Risk Premium Report Study with the Regression Equation Method button on. This would estimate the cost of capital for small and very small businesses.”35

| Cost of Equity(%) | |

| Risk-free Rate of Return | 3.0 |

| Common Stock Equity Risk Premium | 6.0 |

| Small Stock Risk Premium | 5.4 |

| Industry Risk Premium | 3.7 |

| Company Specific Premium | 0.0 |

| Total Cost of Equity | 18.1 |

FIGURE 8.8 Cost of Capital According to Ibbotson's Buildup

It should be noted that caution should be applied when using extrapolations beyond the data. There is no way to be sure the extrapolation is correct but it is the best that can be done. This estimate then needs to be screened to see if the figure provided by the system makes sense independently. Again, this is a problem with the income model, not Cost of Capital Navigator data. Review the data and use where it affirmatively answers the question, “Does this make sense?”

Figure 8.8 shows a typical Duff & Phelps Ibbotson's process for estimating a buildup. It is further explained below.

Below is a high level summary of a common set of buildup classifications.36

- The first tier of the buildup method is the risk-free rate. This is usually derived from the current day or beginning of the month or year rate of 20-year treasury bonds.37 Sometimes 10-year term or 30-year term T-Bond rates are used. Duff & Phelps have a “calculated rate” that can be used with their version of cost of capital.

- The second tier is the equity risk premium, which is the additional risk premium that needs to be paid to invest in large company stocks over long-term government bonds. The selected rate needs to correlate with the risk-free rate selected.

- The third tier is a size premium or small stock risk premium which is an additional risk premium assessed for smaller businesses. This data is generated by breaking down equities by total market value of an equity into deciles and then further breaking down the 10th or smallest decile. Again, this needs to be correlated (same start date and data set) with the first and second tier selections made.

- The fourth tier is an industry risk premium which calculates an adjustment for industry based on the industry beta. Beta is the ratio of the particular stocks correlation of movement with the market. The market is 1. If the stock swings more than the market over time, the beta is above 1. If less than the market as a whole, it is below 1.

- The fifth tier is then the company-specific risk premium, which is an adjustment based on the subject company's soft data and financial results, as interpreted by the valuator's judgment. It should be emphasized this is company cash flow risk going forward, not the owner's or any shareholders' cash flow risk which can be quite different.

Not all methodologies have multiple tiers. Each of the tiers have variations in how they are calculated under the different buildup methods.38 Extensive information is provided by most data sources on their website or in their publications.

The first two tiers are quite established and need no further comment at this time. Most valuators appear to respect Duff & Phelps' work on the calculated risk free rate but use 20-year t-bonds for the rate. The large cap equity risk premium is firmly established.

The third tier, size premium has recently had questions asked about its existence. Apparently in the decade of the 1980s, small capital stocks actually had lower returns than large company stocks. This may be due to popular investment strategies that were heavily promoted at the time. Long-term data and data since the 1990s show a size premium.39 For middle market companies, the jury may still be out at least with certain data start dates, but most valuators agree there is a size risk premium for small and very small businesses.

The fourth tier, industry risk premium is used by many valuators. Again, the question should be, does the industry risk premium make the comparable data more or less like the subject company? Remember this data is pulled from very large chains and companies. For instance, the restaurant industry risk premium is -2.00. If the subject company is a McDonald's or perhaps even a Subway (the oversupply of Subways may have changed this performance in recent years), perhaps the business does have a below normal volatility. But small local independent restaurants do not. For an independent restaurant, the SIC Code 58 Eating and Drinking Places Industry Risk premium may not be reflective of their risk.

When in doubt, you can look up the companies compiled into the industry data and the number of companies the data is based on. In addition, sometimes surprising companies are in the classifications. In a recent look-up for general contractors (by SEC Code as required), the companies in the category were primarily large homebuilders. Not general contractors.

The fifth tier is the specific company risk premium. Pratt, Hitchner, and Fishman indicate that the typical inside range of values for the specific company premium is 1–6% with an outside range of 0–10%.40 They further indicate that a negative, specific company risk premium does rarely occur.

A few courts have ruled against the use of the specific company premium. This is understandable, for while it is common practice, there is no real data supporting most of the adjustments other than “this is how it is done,” but that logic is a bit circular.

Specific company premium is where valuators adjust for the differences in risk to the large public companies and the risk to the small company being valued. These are unsystematic risks beyond the risk captured in the larger public stocks and industry adjustments.

This tier is where all the subjective company-specific factors (depending on the standard of value, this may be from the buyer's and/or seller's points of view) are taken into account. These may include adjustments for concentrations, management depth, tax matters, threats to the industry the company cannot adjust to, and so on. A longer list of factors that may apply is given below.

- Growth rate

- Risk of not meeting the growth rate

- Strategic risk

- Changing business model

- Historic growth success/failure

- Financial risk

- Risk of leverage

- Risk of contingent liabilities or lawsuits

- Profitability/cash flow

- One-time expenses

- Casualty loss

- Control systems

- Treasury/loss of assets

- Credit risk

- Ability to obtain credit, loss of credit, loss of lines

- Gross margin coverage

- Operational risk

- Uncertainties from daily activities, human risk

- Owner concentration/goodwill

- Management limitations/leaving

- Lack of insurance

- Labor issues

- Ineffective systems, growing beyond systems

- Recruiting, training, human resources

- Product/service development

- Equipment maintenance

- Purchasing

- Inventory management

- Compliance risk

- Intellectual property risk

- Non-competes, non-solicits

- Industry risk41

- Regulation

- Commodity/supply issues

- Changing technology

- Supply chain

- Owner status/certification-dependent

- Economic risk

- Recession

- Tariffs

- Concentrations

- Customer concentration

- Supplier concentration

- Referrer concentration

- Regional limited location risk

- Key word/search dependent

- Depending on Amazon for sales

Remember, this list of factors equals the total unsystematic risk that cannot be derived from the larger investment market analysis.

Specific company premium is often weighted or calculated using the same techniques discussed in Chapter 6, Market Approaches, the section “How to Present Soft Factor Analysis.” This includes the percentage or direct weighting method, the major factors method, and the list method.