CHAPTER 14

How to Review a Business Valuation

I would rather be approximately right rather than perfectly wrong.

Does this make sense?

Namely, when looking at a business valuation, a sense of curiosity is the starting point of the Art of Business Valuation. A surprising number of times when carefully reviewing valuation reports, the answer to the question is no. This does not make sense.

Sometimes the value determined seems reasonable but the supporting facts and assumptions do not really add up. Other times the value calculated is just wrong. Most of us have read too many reports that seem quite “pretty” and thorough (or at least long) to find upon closer review that they are wanting in their logic, have unsound or incorrectly applied methodology, meaningless subjective weightings, unfounded or unexplained assumptions, and calculations that couldn't be replicated or just don't matter.

Clearly there are multiple levels and reasons to review a business valuation. The steps presented here can be used for internal pre-release checking of the valuation. They can also be used to review other valuators' valuations.

Humans (including analysts) can be swayed and begin to take sides and not even notice they are doing it. Another factor that plays into poor valuation estimates is lack of expertise. Combine a work product that requires many assumptions, multiple methodologies, and a huge variation of types of businesses and size ranges of businesses and it is easy to miss the mark and never even know it.

Mergers & Acquisitions professionals see this all the time with valuations prepared for exit planning purposes. For example, the well-meaning analyst who used large public company guideline comparables for a small engineering firm and then put a control premium on top. Nice theories but the wrong result. (You can't make this stuff up. Even the owner knew that the value did not make sense.)

The aim of this chapter is to allow analysts to overcome these issues in their own work and for all users to be able to spot errors and problems in other professionals' reports.

This section will begin with some larger “jump off the page” type issues and work down to smaller details that may impact value and certainly will impact credibility. I am primarily using a bullet-point format as this is more of a checklist.

WHERE ESTIMATES OF VALUE GO WRONG

Eventually value is calculated with numbers. Because every detail and the fact that every detail and assumption are eventually translated into a number representation, it makes sense that following the numbers is a logical way to review the report and calculations. This does not mean the industry, customer relations, organizational structure, and so on do not impact the value. It means we will look at how they are tied into the numbers with an emphasis on …

Does this make sense?

Most business valuations are going to be in the ballpark, or satisfactory type of work product and opinion. A few will be exceptionally well done. A few will not represent an accurate business valuation or even be close. Remember, the test is not “will this happen” (though “this cannot happen” is a test) but are the fact pattern, assumptions, and value derived therefrom the most foreseeable from what is known and knowable on the valuation date?

Key numbers and areas of emphasis are:

- Selection of the period(s) reviewed

- Cash flow normalization/add-backs used

- Weighting and selection of cash flow measure, including projections

- Selection of methods and then the resulting multiplier, capitalization rate, or discount rate

- Modifying cash flows and valuation method calculations for internal and external soft factors (economy, management, etc.)

- Balance sheet adjustments, such as working capital, inventory, excess assets, including built-in gains tax

- Discounts and premiums.

Each of these areas will be reviewed in detail. There is also the issue of the cumulative effect of assumptions, choices, and even errors that also needs to be monitored.

Jump Off the Page Issues

The following issues need little explanation and, if visible, should be further investigated:

- The wrong standard of value

- The wrong valuation date

- The above two issues seem technical and they are. But think of the value of a restaurant serving a tourist destination on a far-off island the day before and the day after 9/11. Remember after 9/11 no one flew for three years

- Recognize for some planning and divorce matters, the valuation date might “move” over time.

- The cash flow being applied against the wrong multiplier or discount rate (an SDE cash flow being applied to an EBITDA multiplier; a non-tax adjusted cash flow being applied to a standard buildup)

- Almost miraculously better or worse current year or even last two year data

- Hockey stick projections

- Cash flow weighting that is not supported by facts

- Suspicious add-backs, one-time events, and so on

- Unusual or unlikely discounts, capitalization rates, and market data multipliers

- A final value after all adjustments and balance sheet additions (inventory and/or accounts payable) that is above a 100% financed business at 8% (this is extreme, but it happens). Again, the finance method is a great sanity check

- At the other extreme, a long-term high revenue business in a cash industry with very low gross margins and no value. (While it could be a huge discounter, it could have cash leakage.)

- Cherry picking. Namely, almost every choice was favorable to very favorable for a higher or lower value.

All of these issues, other than the first two issues, could be explainable and even correct. But, if these factors are present, look hard before signing that the value found and report is correct.

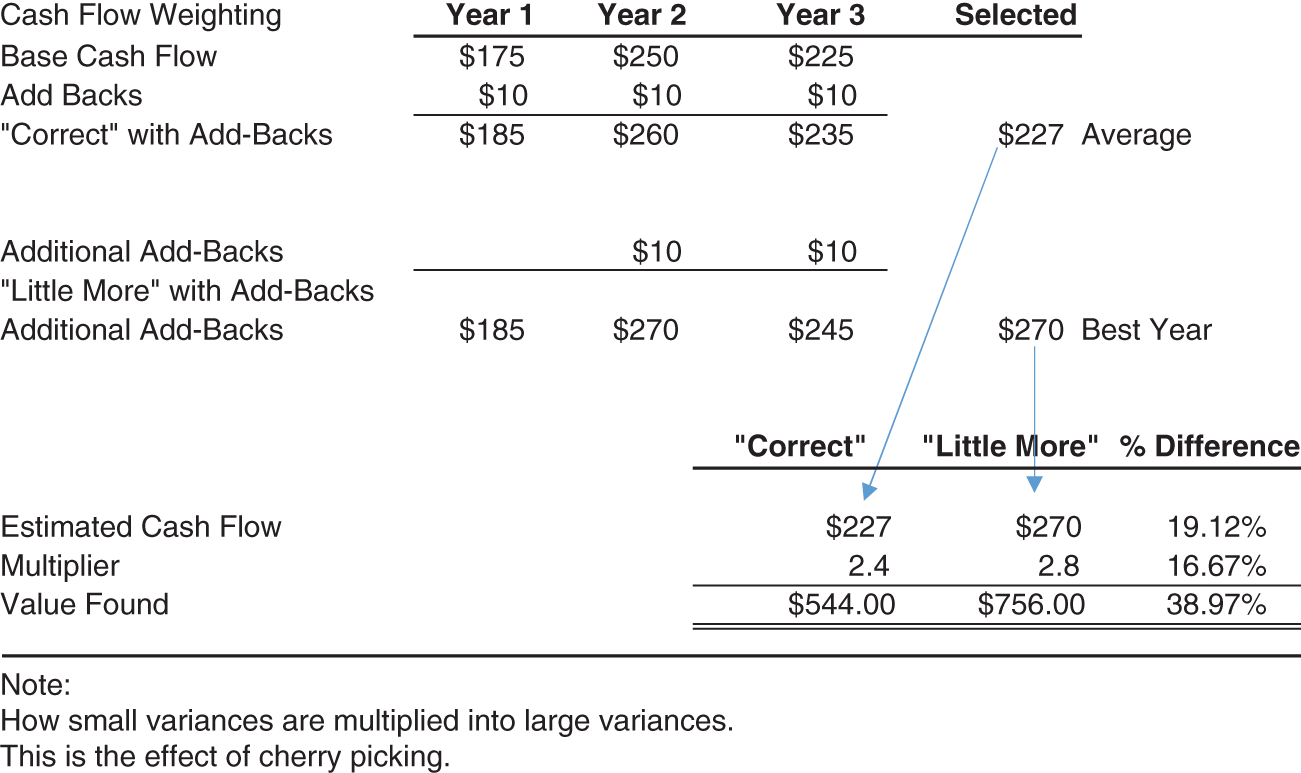

Cherry Picking

Cherry picking is when the analyst consistently chooses a favorable assumption or analysis over an unfavorable one to increase or decrease value. This can be an assumption or choice on any one area but in most cases it is replicated throughout the estimate and report. While performing reviews, keep a tally of the choices made and if they are neutral, unfavorable, or favorable for the direction the preparer may want the value to go, based on the purpose. Also have a column where you check off if the choice was the best choice. Remember, sometimes there really is a very favorable fact pattern for one value or another. Figure 14.1 demonstrates the cumulative effect of cherry picking. Note how small increases in various measures can greatly increase the value found. See Figure 14.2 for a handy form to review a business valuation for cherry picking.

FIGURE 14.1 Estimating the Cumulative Effect of Cherry Picking

The analysis presented in the chapter will indicate measures of the strength or weakness of the overall valuation. Use the form shown in Figure 14.2 and available on the website to track overall integrity as the review is performed. The remainder of the chapter details issues to look for that can be summarized on the form.

| Assumption | Explanation | Favorable | Unfavorable | Neutral | Use? |

| Basic Accounting | |||||

| Periods reviewed reasonable | |||||

| Cash or accrual basis | |||||

| “Miraculous” up or down results | |||||

| Cut-offs adjusted properly (particularly last few periods) | |||||

| Revenues and expenses recorded (cash issues) | |||||

| Revenues and expenses in correct period | |||||

| Math correct | |||||

| Add-Backs Normalization | |||||

| Add-backs tie into statements used | |||||

| Add-backs properly supported | |||||

| Owners' compensation / benefits adjusted | |||||

| Owned real estate / other adjusted | |||||

| One-time revenues / expenses reasonable? | |||||

| Consistent margins | |||||

| Cogent explanations for change? | |||||

| Valuation Matters | |||||

| Correct standard of value | |||||

| Correct valuation date | |||||

| Premise of value | |||||

| Well organized | |||||

| Logical case made | |||||

| Standards (if any) met? | |||||

| Market Method | |||||

| Multiplier consistent with profitability, other factors | |||||

| Comparable data reasonable for size profitability | |||||

| Have comparables been charted by price to cash flow? | |||||

| Soft business factors support multiple selected | |||||

| Cash flow weighting ties into results and future | |||||

| Value found is reasonable | |||||

| Balance sheet adjustments performed (see below) | |||||

| Income Methods | |||||

| Is buildup method accepted and reasonable? | |||||

| Basis for specific company premium | |||||

| Is growth rate supported? | |||||

| Are forecasts supported? | |||||

| Are forecasts reasonable/ consistent / foreseeable? | |||||

| Is the period projected fair? | |||||

| Cap of earnings: is the cash flow weighting reasonable? | |||||

| Is the method tax affected? | |||||

| Do working capital, capital investment, debt support forecast? | |||||

| WACC: are the rates representative of this size business? | |||||

| WACC: is all interest-bearing debt subtracted? | |||||

| Is the value found reasonable? | |||||

| Balance sheet adjustments made (if any – see below) | |||||

| Business Soft Factors | |||||

| Do revenues, gross profits, and profit trends support selections? | |||||

| Do people, processes, and profits support selections? | |||||

| Risk from concentrations | |||||

| Lease, contract, litigation, other deal killers | |||||

| Foreseeable caps on growth (capital, key people, etc.) | |||||

| Owner / management capacity | |||||

| Economy / industry issues | |||||

| Amazon Effect | |||||

| Specific competitor or product issues | |||||

| Marketability issues such as certifications, licenses, restricting transfer | |||||

| Balance Sheet Matters | |||||

| Valuation method consistent with treatment of accounts? | |||||

| Inventory taken, merchantable, correct | |||||

| Working capital estimated / reasonable | |||||

| Accounts receivable collectable | |||||

| Excess assets accounted for | |||||

| Fixed assets marked to market | |||||

| Liabilities paid off or other treatment | |||||

| Personal Goodwill, Discounts, Premiums | |||||

| Does standard of value allow discounts? | |||||

| Are risks double counted? | |||||

| Is selected amount reasonable based on comparables? | |||||

| Concentrations or other unusual discounts | |||||

| Definition of personal goodwill | |||||

| Reasonableness of factors | |||||

| Method Selection, Weighting | |||||

| Are method results close? | |||||

| Would alternative selection materially change the value? | |||||

| Does value relate to price? | |||||

| Sanity check, reasonableness test, other |

FIGURE 14.2 Cherry Picking Analysis Form

Selecting the Periods for Review

This seems pretty straightforward. Select the three or five years before the valuation date. Select the projection period provided by management. In many cases that will be reasonable. However, if data is available, the following review may be very revealing:

- If a year or two was added to either side of the period reviewed, would the resulting cash flows “look” different?

- A quick estimate of the cash flows for those years can be calculated. (EBITDA or SDE using similar add-backs for a very rough cut). Does the resulting revised cash flow support or change your thoughts about the overall cash flow selected? (This will be reviewed in the section, Selection of the Cash Flow.)

- Are the period cut-offs correct?

- Is the transition from reviewed accounting statements or tax returns to the current year company internal data prepared on the same basis?

- Does it appear all data is in the right period cut-offs? While this is assumed to be more of a problem with a cash basis, often underlying assumptions for accrual basis can be manipulated (i.e., percentage of completion for contractors and manufacturers, actual capturing of expenses, etc.).

- Information technology companies often bill and are paid in advance, contractors can have billings in advance of completion (where the liability may not be recorded). These and other factors can require cut-off (and related balance sheet) adjustments.

- Sniff test work in process schedules when available. Is it consistent over periods? Recognize high-level industry managers can walk a site and quickly access the percentage of completion for most trades. Was that done by impartial people? If multiple WIP schedules can be obtained, do they tend to show losses or reductions in profit first appearing at 80% complete? This often indicates poor management and other problems

- Beware if current year gross margins or overall results are dramatically changing from historic data. Maybe the current year should not be part of any cash flow weighting

- Is the cost of goods sold, inventory, work in process, etc. properly established? The retailer that uses 35% COGS because it always seems to work out and has never done a physical inventory has very suspect earnings.

- Do industry and economic data and projections support the periods selected?

- For instance, doing a cut-off of a projection the year before a recession for an electrical contractor may give an unfair view. Same with a historic cash flow that selects only one very high cash flow year immediately prior to a recession or for a company that clearly had a one-time boost to earnings.

- Remember, valuation looks to the future with what is known or knowable.

- Mediators, courts of equity, and other reviewers may view what actually happened in the next few periods as knowable even if different from expert and management projections. If it would influence your thinking, it might influence them

- Valuators stand up for their valuation conclusion not the client's wishes.

Add-Backs Used

This is an obvious area to examine. Some add-backs are quite basic and straightforward. With small and very small businesses, many add-backs can be difficult to verify and then questionable: does it really meet the definitions and should be added back?

- Start by reviewing all math in the report.1 Have someone duplicate every addition, subtraction, multiplication, and the like. Surprising things may be found.

- Do the add-backs selected tie into the related expense items on the underlying financial statements? Sounds basic but often they do not.

- Is unreported cash involved?

- If so, what is the support?

- If proven for revenues, could there be expenses paid in cash too? (This is very common.)

- Are there support documents such as POS reports or even cash register tapes, credit card statements, delivery tickets, journal entries, reconciliations, sales tax reports, tax accountant work-papers?

- What support is there for discretionary add-backs?

- Family members' salaries. W-2s show payments but is labor being performed and can it really be determined? Sometimes it is clear such as children who are away at college, though with virtual jobs, even this is less clear.

- For EBITDA discretionary compensation-type adjustments, does the adjustment include benefits or not? Should it? $25,000 family health insurance plan is a big percentage when it is being given on a $75,000 salary.

- Is the comparison right for labor value estimates reasonable? (An association representing very large electrical contractors had a typical President's salary at $400,000, which is more than most 15-person electrical firm's SDE – this is not reasonable.)

- If the building or real estate (or equipment) is owned by a related party, are the payments between parties at market? How was this determined?

- Is everything properly reflected on the balance sheets?

- One-time revenues/expenses

- Are they really one-time? Is the claimed item really unusual for the trade or business being reviewed? Does the fact pattern really support “one-time”? What happens if the review period is expanded?

- Some companies (infrequent with small and very small businesses) “manage” their earnings and have tucked away earnings offset by contingent liabilities. These can be difficult to find (do not assume they show up on reviewed financials as they often do not) but should require at least moving the earnings between periods.

- An advertising agency offset $500,000 of earnings due to a magazine vendor payment contingency (really?) and recognized the earnings three years later when the business trends were sliding down. The transferred earnings moved EBITDA from $1,000,000 to $1,500,000. A very material difference in the earnings per period fact pattern.

- Are all add-backs included?

- Often missed items include the employer portion of payroll taxes.

- Auto expenses can have many pieces, insurance, repairs, gas, lease.

- Cost of goods sold can have personal swimming pools, second or new homes and other benefits (often bordering on tax fraud) buried in them. Search contractors' COGS carefully if telltale signs or trust issues (this quickly becomes a forensics matter) when appropriate for the purpose.

- Question one-time expenses and revenues. Do not assume they will be clearly identified or in other income or expense.

- Check miscellaneous or other expenses, particularly if very large for hidden add-backs.

Weighting and Selection of Cash Flow Measures, Including Projections

One of the simplest ways to adjust a valuation is to weight the cash flow wrong. This can be very effective and not always obvious to inexperienced eyes. See the section, Weighting the Cash Flow, in Chapter 6, Market Approaches to understand the power of this error. Adjustments include:

- Weighting for the market method or capitalization of earnings method:

- Do historic result trends support the weighting?2

- Does the weighting tie into economic and industry projections?

- If the review period was expanded, would you use the same weighting?

- Remember this is future-oriented. There may be major events that will change the future from the historic. (When would these be known or knowable?)

- Forecasts (high level review, see the section, Review of Forecasts, in Chapter 8, Income Approaches, for a detailed review):

- Do the forecasts tie into historic data?

- Do the gross margins, expenses, profits tie into historic percentages?

- Was a set ratio (i.e., 3%) used to increase all expenses?

- Does the forecast form a hockey stick (hard to believe but they often will)?

- Does forecast preparation date, preparer, purpose, and so on add credibility or reduce credibility?

- Is there a history of forecasts and, if so, what does that indicate?

- Do the economy and industry data support the forecast?

- Do the “reasons” provided for changes make sense and is there supporting evidence?

- What actually happened since the forecast? (Again, this ties into the known or knowable issue in business valuation. The definition of known or knowable may be liberally construed by courts of equity trying to provide fairness.)

Selection of Methods: The Multiplier, Capitalization Rate, or Discount Rate

Method selection seems basic but results can vary dramatically between different approaches and between the various methods within an approach.

- Method selection and then the multiplier, capitalization rate, or discount rate:

- The market method

- If the business is in a comparable rich industry, be concerned about why the market method was not used. For all the cross-examination issues, charting the market method results is quite persuasive and may provide less wiggle room than other methods.3

- Do sufficient market comparables exist? While six to ten is often considered a minimum, maybe fewer comparables can still provide guidance.

- Are the selection criteria reasonable? Remember increasing minimum sales revenues often increases multiples. Was a reasonable sales revenue range selected? Was the earnings stream selected representative and reasonable? For instance, revenues are frequently used for tax preparation firms but rarely for construction contractors.

- Are the cash flow multipliers based on similar criteria as the subject company or are there many high-revenue low-earning companies in the sample used? (This often produces high cash flow multipliers.)

- How are “soft factors” tied into the cash flow and multiplier? (See Soft Factors below.)

- What comparables were eliminated from the set and why?

- If “specific transactions” were selected and the small set used, do the criteria hold up as impartial vs. all the comparables or vs. other sorting of the comparables?

- What is the variance from the comparables median or mean multipliers from the selected multiplier?

- Do the gross margins and other available indicators tie into the selected multiplier indicators?

- Plot out cash flow and revenue multipliers by profitability. The 75th percentile cash flow multiplier is likely to apply to the 25th percentile performing business. Check, as this alone can be a very big swing.

- The income method: calculating the discount rate:

- Which buildup method was selected?

- What is the start date of the data and why was that start date selected?

- If an averaging of methods was used, do the weighting and reasoning make sense?4

- Is it consistently applied?

- First, was the same “chart” or method applied across all buildup tiers and then were the same forward- or backward-looking estimates applied consistently.

- Small company premium: Did the methodology have Section 10 of The Center for Research in Security Prices (CRISP) data further broken down into deciles? Which decile was used and why?

- Recognize most valuators do not use the smallest deciles under the theory that those are very distressed firms as they report net losses and therefore not comparable. While small company premiums may be arguable for mid-market firms for small and very small firms, very few analysts would suggest there is not small company risk.

- Does the industry premium reflect the conditions of your company? That is, risks to national known restaurant chains may not be the same as an unbranded sub-shop. Should this be in the equation?

- How was the company-specific risk rate formulated? Beyond “experience,” what quantitative data was it tied into? If the market method has a reasonable number of comparables, why was that method not used? If it was used as a reasonableness test or otherwise, why not just use the market method entirely? (See Soft Factors below.)

- Income method: calculating a capitalization rate and/or terminal value rate:

- All factors in the income method determining the discount rate should be reviewed.

- How was the growth rate selected?

- This is a very subjective number that can greatly swing value.

- How does it relate to recent actual growth or contraction?

- If it is below 0 or above 6, it is quite suspect in the eyes of the valuation community. Usually 2–3% for mature companies and 3–4% for younger companies.

- For terminal value even though the next year's cash flow is used (with the long-term growth added), remember that the last year of the projection's present value rate is used.

- Are there modifications to the “perpetual” cash flow that should be made (working capital, debt, capital investment) at transition from discrete years cash flow to terminal value cash flow?

- Income methods: all

- Is the cash flow calculated and used consistent with the capitalization rate or discount rate used?

- Has the cash flow been tax affected or the discount rate appropriately adjusted for pre-tax cash flow?

- If WACC (weighted average cost of capital) was used, was the buildup rate increased for additional risk due to leverage and is the ratio of debt reasonable?

- With WACC, is all interest-bearing debt subtracted from the value found to determine equity values?

- The specific company adjustment and the growth rate are both highly subjective, hard to tie into data, and can greatly swing value. That does not mean small and very small businesses should not have those adjustments. Yet reasonable may not be right. But it may be hard to overcome that presumption.

Working Capital, Inventory, Excess Assets, Balance Sheet Adjustments

The general rule is that the assets necessary for the business to function, including current assets (usually accounts receivable, inventory, other current assets) and of course fixed assets, need to be conveyed with the business. Otherwise the business could not earn the money or cash flow that is the basis of the value.

This is modified in that the market method for small and very small businesses using the comparables. These often do not include net working capital. Namely, the seller keeps the cash, accounts receivable and other current assets, if any. In addition, in some databases and many industries, good and merchantable inventory is added to the price.

For most small and very small businesses, debts and liabilities will be paid off at the time of a sale. This may vary with the industry custom, valuation method, and standard of value being used.

The Market Method

- The starting point premise, assuming a private transaction database is being used, that is when recording asset sales, is that all current assets are retained by the seller. In addition, all liabilities are retained by the seller.

- This appears more consistent with smaller companies where SDE is used as a cash flow.

- As companies get larger and EBITDA is typically used, this is less consistent and reasonableness needs to be tested. The rule of thumb finance method is useful for this check.

- Inventory is reported to be sold above the purchase price in some databases.

- Carefully check the comparable database for their treatment of inventory.

- This seems to be more consistent with small companies below $1,000,000 in value.

- Inventory must be saleable. Often deep inventory retailers or parts suppliers will have huge unsaleable inventory.

- Take a used parts/junkyard. They had $3,000,000 of “wholesale sales price” inventory that was constantly being added to. Industry custom is that the first sales of parts from a salvage vehicle are applied 100% to cost so there is no real cost record. But, they could not turn it or discount it to sell at a reasonable pace. Agreed inventory was $400,000 or four months inventory turn.

- Companies with inventory bulges due to seasonality usually have offsetting liabilities and/or reduced capital. Beware of adding the inventory and missing the payable or capital reduction.

- Between $1,000,000 and $2,000,000 of business value inventory is very negotiable.

- Above that, inventory starts tending to be included in the value.

- Check industry custom. Inventory that is the equivalent of “cash,” such as gasoline, perishable produce, and other very quick turn inventory, is often added to the value across all transaction sizes.

- Working capital-type adjustments are common for businesses over $1,500,000–$2,000,000 in value. Companies with excessive working capital requirements (or inventory or capital investment for that matter) will have much lower multipliers as they have less cash to distribute to owners. This size guide is probably due both to the size of the bank lines that would need to be borrowed and the sophistication of buyers.

- Excess assets, whether on a net asset basis or as companies get larger on a working capital basis, are added to the value of the business. If there are more liabilities than assets, the liability would be subtracted from the value.

The Income Method

- Typically, the company is assumed to have a “balanced” balance sheet. Namely, reasonably necessary working capital and inventory is included.

- This method is very inaccurate with very small businesses. Particularly with small businesses with inventory and perhaps accounts receivable.

- As a rule of thumb this method becomes more useful for businesses over $1,500,000 in value.

All Methods

- What standard of value is being used to determine hard/fixed asset value?

- Company vacation and sick leave accruals can be substantial. Has that been accounted for?

- Is inventory merchantable, current, at lower of cost or market, and in reasonable quantities

- For long-lasting inventory, two years on the shelf is a rule of thumb limit used in many transactions.

- For high inventory or high accounts receivable businesses, the balance sheet adjustments can be huge. A typical $7,000,000 in revenues construction subcontractor can have $1,500,000 of accounts receivable when well managed. Whether this is included or excluded in value is a huge swing.

- If the SDE of a small subcontractor is $500,000 and the multiple is 2, the value before balance sheet adjustment is $1,000,000. A “typical” transaction might add $900,000 of the receivables to the price and the seller would collect the other $600,000 directly. That collected portion is more likely to be $400,000 after warranty work and negotiations. So the “value” would be $2,300,000 ($1,000,000 + $900,000 + $400,000). In a strong economy that is reasonable. In a weak economy the multiple will be 1 and the value would be $1,800,000. In a very weak economy, the company would be worth the value of the collectable receivables. Once word is out that the company is shutting down, the value of the receivables would probably fall to 70% so the likely value would be $1,050,000.

- Inventory creates the same issues. Selling the last 50% of inventory in some industries is almost impossible.5

- Are all excess assets on the balance sheet known and reported?

- Are assets on the books and records not actually titled to the company?

- Are liabilities being treated properly?

- They are a usually a subtraction when estimating market value using market methods.

- Income method:

- If small amounts or when for sales with small and very small businesses, the debt is usually subtracted.

- The debt payments may be factored into the cash flow. For small and very small businesses, this often makes more sense for fair value, intrinsic value-type valuations. Sometimes the weighted average cost of capital could be used in these cases.

- Are all liabilities shown on the balance sheet?

- Check for long-term equipment leases.

- If union workforce, pension or other liabilities:

- A small union printer that made $250,000 of SDE had a pension liability of $700,000. The union denied the extent of the liability until a demand letter was presented.6 It took 60 days to receive the reply revealing the extent of the liability.

- Unfunded and/or unrecorded warranty liabilities.

- Unrecorded lawsuits or disputes including employee matters.

- Are balances of interest bearing debt reported properly?

“Soft Factors”

All methods. How are these factors tied into the cash flow and valuation method?

- Do external “soft” factors support or weaken future prospects of the company. The economy, technological change, industry change all fall in these categories. “A rising tide lifts all boats” is a valid but often hard to adjust for factor.7

- Do the company “soft” factors such as management team, history, staff, systems and the like support the multipliers, discount rate, or capitalization rate selected?

- Does the company have concentrations (sales, customers, suppliers, referrers, etc.) that are properly adjusted for?

- How do these two above factors affect the resiliency of future cash flows?

- Does it have a status such as 8(a) or minority owner that might reduce the buyer pool and value?

- Have all material changes such as gain or loss of key accounts and contracts been reported and taken into account?

- Might a franchisor or landlord charge high transfer fees or require expensive upgrades at transfer?

- Check deal killers:

- State or Federal tax issues, lawsuits, undisclosed legal issues, inability to extend real estate lease or other irreplaceable material contracts, licensing issues, employee issues including key employee availability for transition.

- These may lower the multiplier, increase the discount rate, or be adjusted against the cash flow. Do make sure they are factored into the business valuation.

Personal Goodwill, Discounts, and Premiums

Personal goodwill, discounts, and premiums are a very subjective area. Clearly a 5–45% discount or more can greatly swing value found. When personal goodwill, discounts, and premiums apply, reasonableness and “Does this make sense?” must be used.

- Check if the standard of value allows for premiums and discounts.

- Technically, entity-level premiums and discounts may be reasonable even for fair value when comparability or other issues prevail, but this level of parsing may be above a user's comprehension or local court precedent.

- Does the method used warrant a premium or discount to be comparable to the interest being valued?

- Review for double counting. Namely, if the same risk is being adjusted for multiple times. This can occur in the discount or capitalization rate, in the minority discount, or in the discount for lack of marketability or in all three.

- For example, the valuator increased the specific company premium for customer concentration and then took a discount for lack of marketability primarily due to customer concentration. Nice when they put it in writing.

- Is the discount selected on the high, low, or median of the range of discounts?

- After the premium or discount adjustment, do the overall value, return on investment, and other measures make economic sense? While this may be circular logic, this is the most important factor in reviewing a discount or premium.

- Personal goodwill:

- What is the definition of personal goodwill being used by your user (state law or Federal tax law)?

- If there is no non-compete or exit transition agreement or worse yet if the human seller competes, would it damage the company?

- If the answer is yes, tie into the definition of personal goodwill for your jurisdiction and purpose

- Many valuators have a “position” on personal goodwill. I too have an opinion. But, if the definition for a purpose is clear in a jurisdiction, we are not legal counsel and should apply the law as provided. Of course, this too can be argued and even I would have exceptions.

Selection of the Method, the Weighting, and Other Factors

This section will look at the selection and weighting of the methods. We will conclude with a few other factors that have an impact on value found and, more importantly, credibility.

- If for estate and/or gift tax, IRS purposes, Revenue Ruling 59-60 specifies selecting the best method.8

- Many analysts believe, and standards allow, selecting a range of values for many purposes. Therefore, for many purposes valuators perform a weighting of two or more credible methods.

- Are there strong reasons to select the weighted methods vs. other methods?

- If there are large variations between the methods, are the reasons given reasonable?

- What would the effect have been if one method was selected over the other?

- Is the other method or is the less weighted method likely to be materially more correct?

- Is the selected method weighting reasonable?

- For instance, in a divorce, the “out” spouse's advisor put a heavy reliance on the market method revenues; based on a lifestyle analysis (clearly a forensics not valuation method) that indicated profitability but an inability to account for likely cash and show profitability in the company. Certainly, the forum and rest of the fact pattern will be part of determining if this is really reasonable.

- Weighting four or seven methods or more indicates a lack of thought and selection. At a minimum, it strikes the appearance of an averaging of rules of thumb. Blind averaging is not supportable.

- Is the application of the discount, premium, or personal goodwill justified and reasonable in the final weighting?

- Other

- Is the report well organized, does it comply with standards?

- That assumes the report is prepared by someone with standards. (Note many economists and brokers and other knowledgeable people may not have standards.) Are there typos and spelling errors? Maybe whole sentences left in from prior uses of the report?

- Check the math (again) throughout

- Is there an overall logic to the story, situation, or case being presented? Is it consistent? Is it fair and reasonable?

- What are the credentials of the analyst? If in a conflict situation, does the analyst appear to have unusual credibility in general or with the reviewer?

- Take a case where the other valuator was suggested by the judge as a “good guy to use,” but both sides were ordered to obtain their own expert.

- Is the report well organized, does it comply with standards?

- Finally, does this make sense?

- Given the overall fact pattern, would someone pay a price that reasonably relates to the value found, based on the facts and both specified and reasonable assumptions with what was known or knowable on the valuation date?

NOTES

- 1. Many valuators forget to use the “=ROUND” routine in Excel; when this happens their column of amounts will not properly add to the total disclosed.

- 2. In a recent review of a report against an oppressed shareholder, the opposing valuator included in the historic data the fifth oldest year with net income of just $10,000. The first through fourth oldest years all had net income in excess of $300,000. The most recent year had the highest net income with expected growth into the future. He weighted all of the historic years equally. The averaged net income that was used to begin the cash flow calculation was “much less” than the most current historic year. Therefore, it appears (subject to other reasoning) the valuator deliberately started with an amount that understated the net income for the cash flow analysis and understated the ultimate enterprise value. He appears to be acting as an “advocate” for his client.

- 3. See Jim Hitchner, “Cross-examination of the Transactions Method of Valuation,” Family Lawyer, April 29, 2019.

- 4. If all the methods used to estimate a buildup are based on the same underlying data, is averaging more effective than selecting the “best” data source?

- 5. Contrast this with furniture “going out of business sales.” Specialty liquidators will sell the company inventory and assorted new cheap inventory paying a commission on the new inventory during the sale period. Sometimes this results in a higher liquidation value than otherwise would be estimated.

- 6. They acknowledged there was “something” due.

- 7. Commonly attributed to John F. Kennedy who used it in a 1963 speech. His use was more general economic theory than concerns about business cycle effects on valuation.

- 8. Rule 59-60, Section 7 Average of Factors states that, “Because valuations cannot be made on the basis of a prescribed formula, there is no means whereby the various applicable factors in a particular case can be assigned mathematical weights in deriving the fair market value. For this reason, no useful purpose is served by taking an average of several factors (for example, book value, capitalized earnings and capitalized dividends) and basing the valuation on the result. Such a process excludes active consideration of other pertinent factors and the end result cannot be supported by a realistic application of the significant facts in the case except by mere chance.” I do not agree with this statement but it is the rule.