Figure 18-1: Retrochoir, Wells Cathedral

When I first walked into Wells Cathedral, I was so overwhelmed by the central arches that I had to walk away, re-establish my bearings, and collect my thoughts before returning to photograph them. I wandered to the far-east end of the cathedral, where I was equally overwhelmed by the forest of columns and arches in the retrochoir and the magnificent luminosity of it all. They seemed alive and exuberant to me, like fountains or fireworks. This became the first exposure I made in the cathedral before returning to photograph the central arches. This started my study of the English cathedrals, a subject matter I never would have guessed to be of interest to me.

CHAPTER 18

Toward a Personal Philosophy

![]()

THIS CLOSING CHAPTER BRINGS THE BOOK FULL CIRCLE. We started by inquiring into ourselves—our own personal interests—and asking what we wanted to say about them and how we wanted to say it. Then we delved into the techniques and considerations that translate those desires into visual statements, and not mere “pictures.” Then we engaged in some philosophical thoughts about art and creativity. In this chapter, I hope to suggest avenues for improving your vision in areas that already interest you, and for drawing inspiration and insight from areas you may have never previously considered.

Flexibility

To my way of thinking, maintaining flexibility in every aspect of photography is the best gift you can give yourself. Avoid limits; avoid boxing yourself in. Try to avoid saying, “I won’t do this” or “I won’t do that.” We all tend to place limits on ourselves unintentionally; let’s not do it intentionally. Of course, whenever you choose the things you’ll do, inevitably, you also choose what you won’t do. You can’t photograph everything; you can’t print everything; you can’t experiment with every approach. But you can keep an open mind and you can periodically delve into areas that didn’t attract you previously. Allow that flexibility.

![]() Maintaining flexibility in every aspect of photography is the best gift you can give yourself.

Maintaining flexibility in every aspect of photography is the best gift you can give yourself.

Approaches stressed in earlier chapters—exposing negatives higher on the scale, using the full negative scale available, pushing the histogram to the right, always shooting in RAW for best printing results, using the appropriate printing controls, playing with toners, etc.—expand your flexibility by allowing you to photograph in the widest possible range of lighting conditions, and to make prints with the widest possible approaches. A simple technique like cropping keeps me from being beholden to the shape of the camera format or the lenses available to me at any time. It gives me greater flexibility, thus expanding my artistic possibilities.

Don’t be hobbled by thoughts of consistency. Emerson said, “A foolish consistency is the hobgoblin of small minds.” For example, my negatives are wildly inconsistent in average density. Much of that inconsistency is intentional; if I want expanded contrast, I expose the scene in the mid-zones and then greatly expand development, yielding a very dense negative, but one with the best possible contrast increase. I can then print those high densities down to the values I desire. So “inconsistent” negatives can produce better prints. That’s the type of flexibility I desire.

What about multiple-negative prints, negative prints, time exposures that may exploit movement, double or multiple exposures, collages, mixed media, or any other type of imagery you can conceive? Try them! Try crazy ideas. Most will fail, but some will work and will launch you into new realms of fun and creativity.

Visual Arts

The most obvious place to search for ideas and inspiration is the visual arts. Visit museums and galleries. Look at art books, but don’t just look at the images, read the text as well. Sometimes the thoughts expressed are even more valuable than the imagery. Look beyond photographs to paintings, drawings, lithographs, and sculpture. They all have lessons to teach on composition, lighting, movement, and color. The same philosophical and compositional elements underlie all visual art forms; they are related, and you can learn from any of them.

I suggest emphasizing the study of great photographers of the past—Berenice Abbott, Ansel Adams, Diane Arbus, Eugène Atget, Bill Brandt, Margaret Bourke-White, Frederick Evans, Josef Koudelka, André Kertesz, Imogen Cunningham, Walker Evans, Josef Sudek, Paul Strand, Edward and Brett Weston, Minor White, Ernst Haas, Henri Cartier-Bresson, Frederick Sommer—as well as contemporary photographers. Pay particular attention to those whose field of interest parallels your own, but study the others, too, looking for new ideas and interesting approaches. Don’t become so thoroughly involved in only their subject matter that you can’t learn from their approaches to light, texture, composition, mood, dynamics, and other aspects of seeing and feeling that you can apply to your work.

Be cautious about including illustrated travel books in your studies. There are a number of coffee table books that are exquisite to peruse but that don’t exhibit the highest artistic standards. Enjoy them, as I do, for their exposition of scenic areas, but don’t rely on them for fine photography because they tend to focus on places photographed on bright sunny days with blue skies, but rarely with interesting lighting. In essence, these are wonderfully done postcard picture books.

Try to see original prints whenever possible rather than just looking through books. Though the reproduction quality of books has improved greatly, nothing compares to the photographer’s own prints. In the original prints you’ll see not only the composition, but also the tonal richness and the hard to define but easy to see quality of a fine photograph.

Whether you look at books or the originals, please don’t look at photographs or paintings like most people do—flipping through pages or walking slowly past the originals hung on walls, looking mindlessly at everything and seeing nothing. Study them. Even if you have time to study only a few and must miss most of the others, study those few with care. Ask yourself if they are worthy of greatness and look them over carefully before rendering a decision. What does the photograph say to you? Is the composition good? Is it unified? Does it show insight on the part of the photographer? If not, why not? It will prove far more valuable to analyze a few photographs carefully than to peruse dozens of them nonchalantly. It always seems strange to me that so many people go to galleries without knowing how to look at what’s in front of their eyes—and then they come out yawning, bored with their waste of time.

Look for personal appearances by noted photographers, and even by “unknowns” who are yet to be famous. Universities, museums, and galleries often present lecture series in which photographers present their work and discuss their philosophy and approach. These lectures not only give you greater insight into their work, but may also stimulate ideas for your own work. Sometimes a lecturer will state a well-known idea in a slightly different way that “clicks” with your thinking. It could open up new avenues of thought for your work. Alternatively, a lecturer may express ideas with which you thoroughly disagree, but which help you articulate your own ideas more clearly.

Nonvisual Arts

Beyond the obvious benefits of seeing great art (painting, photography, lithography, sculpture, etc.), look to other art forms for insight and inspiration. There’s a long history of music inspired by literature, and there’s no reason photography can’t draw from both literature and music. After all, our life experiences all mold the type of person we are. If we incorporate our understandings and revelations from other art forms, we can expect new insights and new directions. Composers and writers attempt to do much the same thing that photographers do: make personal statements about the world around them. Surely there are lessons to be learned from their efforts.

Music can offer extraordinary insights. I believe that I evolved a greater understanding of subtlety in printing as a result of hearing the intricacies of fine orchestration. I also feel that this understanding has been heightened in recent years through my growing interest in and love of chamber music; when only a few instruments interact, I can hear each of them individually along with their mutual interactions. The interplay of harmonies, counterpoints, rhythms, melodies, and phrases seems to have many counterparts in the interplay of lines, forms, tones, colors and other photographic qualities.

How has this given me insights into printing? I have listened to the same musical composition played by different orchestras, ensembles, or soloists, each with different interpretations of the original score. Often, I have fantasized about making the ultimate recording of any one of these pieces by selecting an opening performed by one group, a closing by another group, a crescendo by still another, and so forth. I have directly translated that concept to printing in both the digital and traditional darkroom by optimizing each section of the image for maximum effect. Some parts have to be quieted down so that others can glow with brilliance. There must always be a balance between overall brilliance and the ultimate feeling that I want to convey in the print. In that manner, classical music—particularly chamber music—has given me great insight into my approach to postprocessing and printing images.

Relationships between music and photography have long been recognized. Ansel Adams’s famous negative/print analogy—“The negative is the score; the print is the performance”—is but one famous example. Adams was a gifted pianist as a younger man, with enough ability to give public recitals and concerts. Don Worth was a gifted pianist as well, as are Paul Caponigro and Charles Cramer today. It’s no coincidence that such outstanding photographers also have great talent in music. Most photographers who lack talent as musicians can still draw from their interests in music. This is true whether the genre is classical, jazz, electronic, avant garde, hard rock, country-western, or any other type.

I suspect there are very strong relationships between the type(s) of music you listen to and the photographs you make (or want to make). The relationships may be subconscious, but with effort I believe you can define them and apply them to your photography. Whatever music you find enjoyable, you can probably find some surprising insights in it that can be applied to your photography.

I feel that much of my work in the English cathedrals was heavily influenced by classical music. I saw musical relationships in the interactions of the columns, arches, and ceiling vaults, and with the play of light upon these forms. The relationships changed with every step I took, so that I felt I could control the visual music by the placement of my camera—a half step to the left, up four inches, forward just a bit. Then there were no inharmonious intrusions, no harsh dissonances to mar the score—only a symphonic flow of lines and forms, brilliantly orchestrated by the soft light filtering through the stained glass windows (figure 18-1). In the cathedrals, I was as much a conductor as a photographer, but I must admit I had quite a score with which to work.

At the turn of the last century, photographer Frederick Evans worked with the same “score” and produced quite a different “symphony.” Using uncoated lenses that produced flare whenever exposed to a light source, printing on platinum papers, and working in smoke-filled cathedrals (due to candles, rarely used today), he produced prints that let viewers almost experience the air within the space. In fact, it appears that Evans photographed the air between him and the architecture, as well as the light filtering through the air, rather than the architecture itself. His images are quiet, introspective, and thoroughly magical.

![]() In the cathedrals, I was as much a conductor as a photographer, but I must admit I had quite a score with which to work.

In the cathedrals, I was as much a conductor as a photographer, but I must admit I had quite a score with which to work.

It’s possible, perhaps probable, that a different printing of my own negatives would produce yet another interpretation of the cathedrals. I haven’t attempted the project because I can’t see them any other way. But following Ansel’s analogy, several years ago I did spend time in the darkroom attempting various printing results from the same negative. I was spurred on by my encounter with several recorded versions of Schubert’s string quartet #14, titled Death and the Maiden. I found that differences in tempo, emphasis, timbre, and dynamics gave each performance a wholly different character, and I wanted to see if the same would hold true of different prints produced from the same negative. Indeed it did, and I was amazed by the different interpretations a single negative could yield.

Years ago, John Sexton carried this type of experiment further. Prior to a workshop, he would send copies of one of his negatives to more than 10 students, asking them to make a print of it in whatever way they chose. Cropping, burning, dodging, toning—everything was up to the students. The variation in “performances” was quite remarkable. (But of course, none of them were actually at the scene when the photograph was made, so none of them could have gained any idea of how they would have interpreted the scene had they experienced it. So while this exercise was both interesting and instructive, it was also limited.)

Does music evoke mental pictures for you? If the answer is yes, I suspect you have a strong proclivity for drawing photographic insight and inspiration from music. It is unlikely that this will produce new and wonderful photographs for you immediately, but try to open up to the possibilities that music offers. It will prove its worth over time.

Literature is another area from which artists have historically drawn inspiration. Any form of literature can provide it. I have long been fascinated by Japanese haiku: three-line poems with only 17 syllables total. The three lines have five, seven, and five syllables respectively. There are, of course, variations of this basic structure, but all haiku stay close to these rules.

Haiku are designed to evoke imagery. They have an uncanny ability of enticing the reader into conjuring up detailed scenes that fit the concept of the words. It’s apparent that in a poem of only 17 syllables, little can be said. The haiku poet must allude to something without spelling it out in detail. He must build a skeleton structure and allow the reader to fill in the rest. This not only allows for widely varied interpretations, but also allows the reader to become involved in the creative process. If you think about it, that lesson can be applied to photography. Let’s look at several haiku to grasp the meanings better. I urge you to read each one slowly and think about the mental picture it conjures up before going on to the next one.

A lightning flash:

between the forest trees

I have seen water.

Masaoka Shiki

A man, just one—

also a fly, just one—

in the huge drawing room.

Issa

Small bird, forgive me,

I’ll hear the end of your song

in some other world.

Anon

A bitter morning:

sparrows sitting together

without any necks.

J. W. Hackett

No sky at all;

no earth at all—

and still the snowflakes fall . . .

Hashin

Each of these haiku paints a vivid picture, but when you stop to think about it, you painted the picture. The poem only stimulated your imagination. It built the structure, and you filled in the details. This bears a close resemblance to the wonderful quote by photographer Ernst Haas: “The less descriptive the photo, the more stimulating it is for the imagination. The less information, the more suggestion. The less prose, the more poetry.” Haiku fits that description perfectly. Do your own photographs come close?

How often do your photographs say everything, leaving nothing more for the viewers? If you’ve said it all, taking the creativity away from the viewers, you can only expect a quick glance before they move to the next photograph.

The lesson I received from haiku is to say enough to interest viewers, but to leave enough unsaid to allow creative seeing and interpretation. Let them spend time thinking about it. Let your work excite and stimulate them, but leave them an opening for their own creativity.

Haiku is not the only form of literature that contains profound messages for working photographers. Other forms of poetry, as well as novels, philosophical writings, etc., all offer new ideas. They reside on the pages like fruit on the trees: you just have to find them, pick them off, and incorporate them into your way of seeing.

Expanding and Defining Your Interests

In chapter 1, I devoted a substantial section to determining your interests. I’d like to return to that from a different viewpoint, and perhaps one that goes further. I’ve long felt that most people segregate their lives, putting their work in one place, photography in another, music in a third, other outside interests in a fourth, etc. I think that by integrating your life to a greater extent you can draw from multiple areas and apply the lessons to each of the others. The nonvisual arts provide perfect starting points for this integrated approach. We are all multifaceted people with a variety of interests, from politics to the arts, from financial investments to recreational pleasures. No doubt some of these interests have greater potential for a visual dialogue than others, but many have potential beyond our expectations.

In our lives, we almost have to segregate these varied interests, but in so-called primitive societies, they intermingle as one. Art, music, religion, food gathering, birth, marriage, and death are all intertwined. Each represents an essential part of life, and none can exist without support from the others. Why we have evolved into a civilization that segregates these aspects of life could be a lifelong study for an anthropologist. But I feel that those of us who are seriously interested in making photographs can benefit greatly by trying to integrate the many facets of our own lives.

What are your interests? Do you find any visual qualities in them, whether or not you see them as photographic qualities? If so, there may be ways to make comments on them with your camera. My outside interests—natural history, the cosmos and the subatomic, architecture—found photographic expression, and I feel that you can have the same gratifying experiences if you pursue your interests actively.

I wonder how many people try to find things that can be photographed where they work—where they spend nearly half of their waking hours. How many people look for photographic subjects around the house or in their neighborhood? How many people probe their general interests—or their everyday environment—for photographic possibilities?

The canyons were special to me, as were the cathedrals, which I discovered almost simultaneously. Prior to that, the natural landscape served as my main source of imagery, and it still forms the central focus of my photography. Each of these areas—as well as my work in urban areas—has opened up new avenues for me that have great importance and meaning.

Nature draws me because I love the beauty and drama of our planet, and I abhor the way we are defiling it. Yet, it has always been difficult for me to photograph the destruction. I don’t like spending hours in the darkroom just to make a print that looks awful! I always wanted to make some visual commentary on humanity’s disregard for the land, but it remained beyond my grasp until rampant development around my home in Agoura, California (from 1980–1982) pushed me over the brink. Then, for the first time, I became so angry that I photographed things I hated: rolling hills once covered with oaks and wild grasses, bulldozed into bare plateaus; homes looking like they came from your old Monopoly set plunked down in rows with concrete block walls surrounding each one like miniature prisons; telephone and power wires hanging in the sky (figures 18-2 and 18-3). Even those photographs are meaningful to me, but I don’t like them. I don’t like what they represent. They’re purely documentary, borne out of anger and frustration of witnessing pleasant natural land turning into rather wretched suburbia, while reading the words of businesspeople referring to such desecrations of natural beauty as “improvements.”

In 1999, I went a step further. After an extended environmental battle that I headed, political interests overturned, rewrote, or ignored existing laws that would have protected the environment from a massive gravel pit and quarry, in the state of Washington, where I had moved a decade earlier. The permitting of this illegal project drove me to make a series of photographs that were not of the project itself, but rather designed to convey my anger, anguish, and torment over the way politicians crushed both the public and the environment with their outrageous decisions.

Figure 18-2: Oaks and Hills, Agoura

Gently rolling oak-covered grasslands northwest of Los Angeles create some of the most quietly relaxing landscapes anywhere. Such rolling hills run for hundreds of miles northward, up to San Francisco and beyond. But they are being cut down, scraped, and developed into suburbs, car dealerships, business parks, and shopping centers. The natural environment is rapidly disappearing. This photograph was taken near my home—a suburban tract that once looked like this—in the late 1970s, shortly before this location, too, fell to the chainsaws and blades.

Figure 18-3: Monopoly Homes, Agoura

Looking like pieces out of your old Monopoly game set, new homes sprang up, almost pushing up against one another, to replace the natural landscape. Each featured a high concrete block wall surrounding the home, turning the development into a set of prison cells, but referred to as “privacy.” (At least there was no barbed wire atop the walls.) Streets of the tract were given names such as “Shady Oak Lane,” substituting a pleasant name for the reality that once existed prior to the development.

Figure 18-4: Ghosts and Masks

This image is one of a series I made in response to a major environmental battle I led—and lost—during the 1990s. Our environmental group won every legal battle against a proposed gravel pit and hard rock quarry, but county politicians altered existing laws and ignored others to grant the permit. The photographs I produced are my “primal scream.”

These photographs are details of burls on a small log I found on my own property in the state of Washington. Though they are all made under soft light conditions, they are printed with exaggerated contrast levels—including deep blacks devoid of detail and light grays glowing out from the blacks. The bright whites in these images are generally products of bleaching to shocking tonalities, but the predominant tones of each image are dark because I wanted to avoid tonalities that might be interpreted as optimistic or positive (figures 18-4 and 18-5).

I presented 10 of these images as my “Darkness and Despair” portfolio in Tone Poems – Book 1. They are far more artistic than the series I did in Agoura and elicit a far greater emotional response from viewers. They are quite abstract—some viewers can’t determine the subject matter—but the universal visual language of sharp contrasts and tightly curved lines expresses my ideas and feelings. Hence, these photographs use a small log for a specific purpose. In essence, I followed Minor White’s dictum of photographing the log for what else it represented.

After Hurricane Katrina ravaged New Orleans and the Gulf Coast of Mississippi, I quickly did a scouting trip for a workshop. The workshop followed several months later. The purpose was to photograph the awful devastation caused by a natural event after years of indefensible human neglect (figures 18-6 and 18-7). It was gut wrenching to see such widespread devastation, and to see that so little changed in the seven months between the scouting trip and the workshop. I hope that these images made an impact, but it appears that government has not been terribly interested in rebuilding New Orleans or the lives of the people who once lived there.

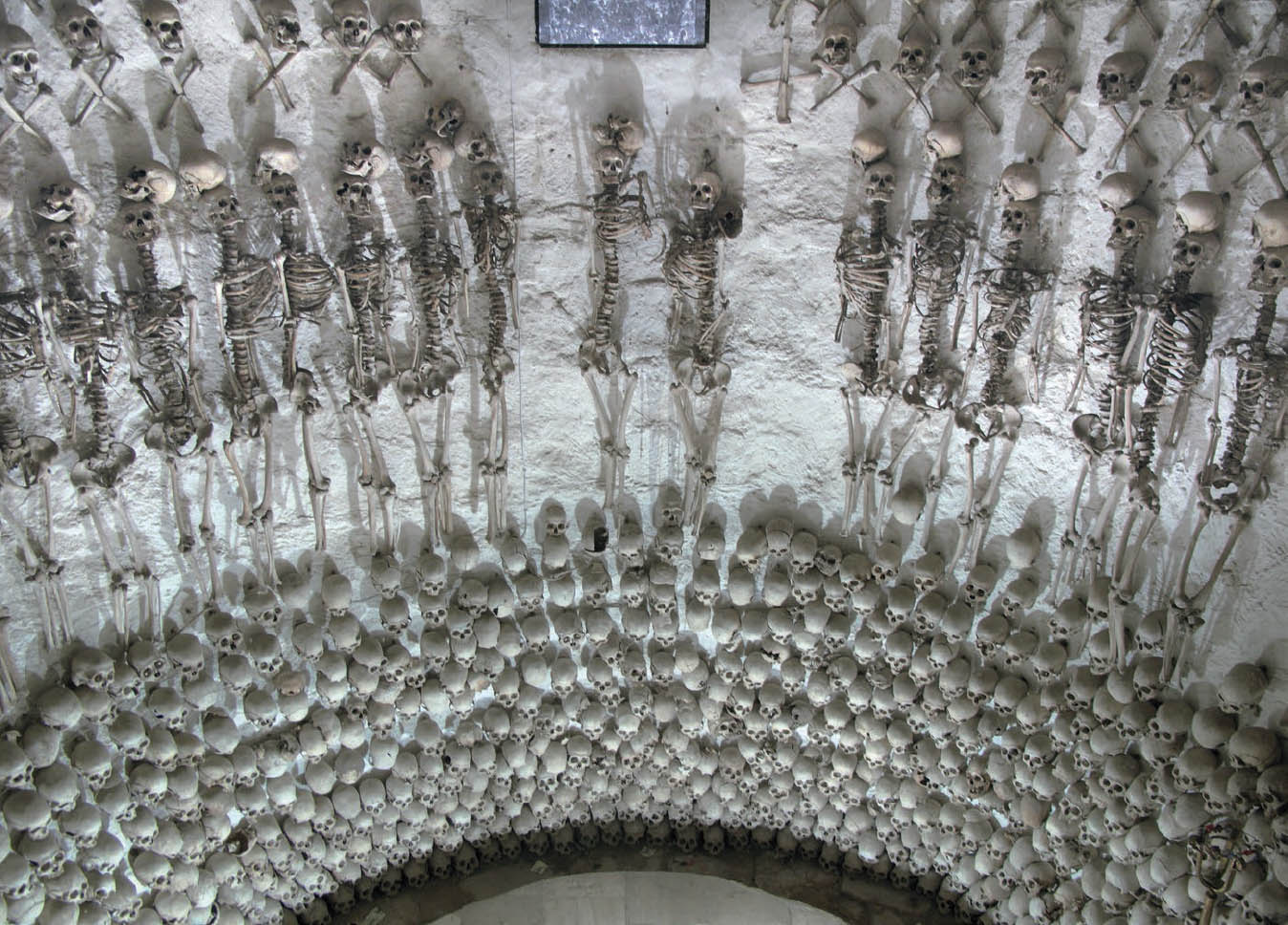

Neither my Katrina images, nor my Agoura images, nor my “Darkness and Despair” images represent my “typical” approach, but they had to be done! I simply couldn’t avoid doing them. Give some thought to what you want to say—with pleasure, awe, sadness, or anger—and how you can say it. Note the things you do aside from photography and see whether any of them have photographic possibilities. Note the things you think about and see whether any of them have visual aspects. Perhaps you can find material objects that relate to those visions. These are the areas where you’ll find your strongest images. Sometimes it may be a surprise encounter with something so unexpected and visually overwhelming that you simply cannot walk away, as was the case for me in a huge church in the remote town of Lampa, Peru, where its most striking feature was a three-story display of human skeletons, skulls and bones (figure 18-8). It was simply too bizarre and too macabre to pass up.

Figure 18-5: Distortion and Desperation

This image in my “Darkness and Despair” portfolio is meant to show the turbulence, horrors, and distortions caused by the illegal political decision to permit the gravel pit and hard rock quarry. The affair proved to me that when big money is involved, there’s no difference between democracy and dictatorship. The entire portfolio derives from close up images of burls on one small log I found on my property, none more than four inches long.

Figure 18-6: Destroyed Home, Ninth Ward, New Orleans

The family photograph on the dining room table, likely placed there after the flooding subsided, had a strong emotional effect on me. It was as if the family had come alive before my eyes, seen in happier days. I never walked into the house and never touched a thing. The image shows exactly what I saw from the doorway.

When you do find a photographic possibility, work with it for a long time, if possible. Try to make a project of it. Study it. Photograph it in every way that has meaning to you—at different times, under a variety of lighting conditions, with an assortment of lenses, and anything else that may produce interesting and meaningful images. Don’t just make one or two photographs and drop it. Keep going back to search for new possibilities. You may be amazed at how fascinating the process proves to be.

Figure 18-7: Multipurpose Room, Thomas Hardin School, New Orleans

This room had served as an elementary school cafeteria, auditorium, and gymnasium. Caked, cracked mud covered every horizontal surface and stained the walls almost to the ceiling. None of the photographs I made following Hurricane Katrina was a pleasure to make. But I felt they had to be made.

Too many people shoot randomly, snapping whatever happens to strike their fancy and failing to look deeply into any specific subject. It turns out that going deeper into a subject can be an exhilarating experience. It’s a form of personal research, personal involvement, personal dedication, and above all, love. By the time you complete your project (if, indeed, you ever complete it), you’ll know it so well—more than anyone else—that you’ll truly love it. I feel the best work always springs from that level of personal involvement.

Figure 18-8: Lampa Cathedral Skeleton Display

This three-story-high display dominates the center of the huge church in the Peruvian town of Lampa. I had no idea what the display meant, but it seemed too bizarre and macabre to pass up. I later learned the display is to honor those of the past who were buried in local graves and those who contributed to the church. It is, therefore, a display of honor.

As you expand your possibilities, you also more accurately define your expressive approach. My own approach is well defined. I like both the art and the craft of photography. I prefer—almost demand—that my prints be sharp and clear. The exceptional rendering power of photography, continuously improved by better lenses and technologies, is one of its chief assets. I like to take advantage of that inherent strength.

I find little appeal in the muddy, out-of-focus creations of the Diana or Helga camera with its plastic lens. Yet I don’t make this preference an absolute rule. On occasion, I’ve produced unsharp images with limited focus because they seemed warranted and effective. Even with my strong feelings about sharpness, I try to maintain flexible thinking rather than rigid rules. The photographs of “Darkness and Despair” have very limited sharpness, especially in their original 16" × 20" size, as they were made with a medium format camera using extension tubes for extreme close ups. I blacked out some of the most out-of-focus areas during printing. Others are visible, but they help create the macabre imagery that I sought.

Sometimes out-of-focus images can be pleasantly appealing, though generally not to me if everything is out of focus. You’ll have to be the judge of what works best for you, and how much can go out of focus (see figure 3-24).

Limitations of Photography

Somewhere in your thinking about how much can be done through photography, there must be the recognition that it can’t do everything. It has limits, just like painting, sculpture, music, and literature, as well as science and technology. None of them can say everything, solve all problems, or reveal all truths. The fact is that photography may not always be up to the task of expressing your feelings, no matter how experienced you become. I still can’t think of a way to express my political views photographically. I feel that an understanding of photography’s limitations is as important as an understanding of its potential.

In 1986, I spent three consecutive days cross-country skiing and photographing in the Canadian Rockies with fellow photographer Craig Richards who lives near Banff National Park, Canada. One day we awakened with the first light of dawn, grabbed a few bites of breakfast, and departed Assiniboine Lodge for a day of exploration and photography before any of the other guests were out of bed. The first hour was drudgery as we laboriously skied uphill through dense forest toward Wonder Pass, several miles away. It was bitterly cold and bleak under a heavy blanket of clouds, and we had constant problems with our skis.

Suddenly, the most remarkable transformation occurred. We broke through the trees into more open country just as the clouds began to part overhead. Wonder Pass lay straight ahead, still a couple of miles away, but visible for the first time. Within seconds the immense wall of mountains to our right opened up, then the slopes and distant peaks to our left. From that moment on the weather became a constantly changing kaleidoscope of calm periods alternating with blizzard-like winds that pushed walls of windblown snow before them. Several times I stood facing the onslaught, only to turn, crouch, and cover my face at the last moment before the blast hit. A minute later it all passed, and I’d stand there cheering with my arms upraised and fists clenched by the exhilaration of it all. Periods of dense fog followed those of crystal clarity. Every moment was special; every vista was extraordinary. It was a day of magic.

At one point I looked uphill toward Wonder Pass for a possible photograph, liked what I saw, but looked to my right before setting down my tripod. What I saw there looked even better, so I skied a few feet to the side to re-position myself. Again I looked to my right, and again found something better! Within moments it happened several more times. Suddenly I realized that I had skied a full 360-degree circle—everything looked better than everything else! It was sensory overload of the highest order. I photographed until I ran out of film. So did Craig. By mid-afternoon we returned to the lodge and sauna, physically exhausted but emotionally charged.

Several weeks later, from my home near Los Angeles, I phoned Craig and asked if he had come away with any particularly strong photographs. There was a period of silence, punctuated by several stutters and stammers, but no words (and Craig is not the quiet type!). I broke the silence by saying, “I’m not sure I got anything, but I don’t really care. It was the day that was so incredible.” “Exactly!” Craig blurted out. “That’s exactly how I feel. I just couldn’t quite find the right words! It was . . . unbelievable! I don’t think I got anything, either, but it doesn’t matter. What a day!”

We both recognized that we were unable to show through our photography what we had experienced. There was too much going on, too fast. No single thing could have been isolated from the ever-changing panorama. It was nature at its most spectacular. Now, if either of us had been equipped with a 35mm camera or a digital SLR, which didn’t exist back then, we might have been able to make the photographs that were skipping past us so quickly. This proves that every camera format has its place, its value. None are better than any other one. Each is a tool. You just have to use your tools as best you can for the task at hand. We had the wrong tools for that kind of day.

I have no regrets that the day yielded no outstanding photographs. The memories are sufficient. Even if I could, I would never trade the experience of that day for a fine photograph—or even several fine photographs. If I had to make a choice between nature and my photography, I would choose nature every time. It’s important to keep things in perspective. To a large extent, my photography is a product of nature, but nature is not a product of my photography.

There are times when the magnificence of nature—or any other subject—can be conveyed with success. There are times when it can be enhanced. Perhaps it could have been on that March day near Wonder Pass, but only by someone who could have maintained his photographic sensibilities better than Craig or I did under those conditions. Perhaps, but I doubt it. There are limits to photography. It’s not always possible to distill so much sensory input into a two-dimensional picture.

There is also another limitation to photography: that of interpretation. You can say what you wish to say through photography, but viewers won’t always get the message you’re trying to convey. This is true of verbal communication, as we have all experienced. Visual communication compounds the problem.

I’ve photographed nature for years—not only recognizing and paying homage to its beauty, but also hoping that others would recognize that beauty as something to be preserved. But I may never see the lush tropical rain forests before they’re completely cut down for palm oil, farms, or ranches. I wonder how long air pollution will go on producing acid rain that destroys lakes, wildlife, and even our own photographs. I wonder what global warming will do to everything, and the horrible impacts it will have on the land, the oceans and the wildlife around this planet. I wonder how many wild rivers I will have the opportunity to see, hear, and photograph before they are dammed and damned as extensions of our indoor plumbing and electric outlets. And how soon will our corporate mentality turn all of the world’s forests into tree farms, ranches, or urban sites?

I have long since accepted the limitations of photography as the perfect vehicle of expression in all situations, but the limits of interpretation are harder for me to deal with. Perhaps a new approach on my part will help solve the problem, and I will surely look for ways to more effectively state my environmental concerns in the future.

There are other minor limitations in photography that are often difficult to detect. One hidden limitation comes via semantics. Landscape photography, for example, is a misnomer. Nature photography is a more appropriate phrase because it is more accurate and allows wider interpretation. My photograph Fallen Sequoias (see figure 3-7) is a landscape photograph, in the usual parlance, yet without the fog that envelops everything in the scene, it would have been excessively complex. Thus, the interaction of the landscape with the ambient weather conditions—nature, in a word—made the photograph possible. It’s not just a landscape, but a nature study, which has broader implications. By speaking of it as a landscape, I believe there is a subtle narrowing of understanding.

Most landscapes truly are broader studies; rarely are they landscapes alone. Interestingly, my abstract canyon photographs are the purest landscape images I’ve produced, for everything within each photograph is eroded rock. Yet they too are broader nature studies to me, because of my interpretation of them as cosmic or subatomic—the embodiment of nature at all levels throughout the known universe.

These are a few of the limitations of photography that I’ve experienced. Doubtless there are others. I feel it’s important to recognize them so you can avoid disappointment with photography’s inability to express every aspect of your thinking. It’s inevitable that such limitations exist. Push those limits to the fullest, but learn to live with them.

Figure 18-9: Mineral King, Sunset

Made in 1969, this image was my entry into photography. This photograph and several others were used by The New York Times as illustrations of this Sierra Nevada mountain valley, which was embroiled in an environmental battle and subsequently added to Sequoia National Park. The Times paid me for the photographs, clueing me in to the astounding fact that I could go camping and get paid for it! At that point, I turned away from missile guidance computer programming, and photography became my new career.

The image, taken just before sunset, has strong side lighting and a dramatic diagonal line of silhouetted trees, adding both depth and a diamond-like design to the photograph. Even today, it holds up as a strong image.

There are also great rewards, to be sure. It’s well known that the work of Ansel Adams was pivotal in preserving vast tracts of land for parks and wilderness, but the process must have seemed glacially slow to him over the years. W. Eugene Smith’s photography of the pollution at Minamata Bay, Japan dramatically alerted the world to the dangers of mercury poisoning, but he was nearly beaten to death by corporate thugs in retaliation. Yet the impact of his work was extraordinary. These are examples of photography at its most effective.

I may have contributed to a successful environmental effort even before I turned to photography as a career. In 1969, I photographed the Mineral King area of the southern Sierra Nevada, a high mountain valley surrounded by Sequoia National Park on three sides. At that time, a major controversy surrounded Mineral King: The Sierra Club wanted it included in the park, but Walt Disney wanted to build the largest ski resort in North America there. I spent several days camping, hiking, and photographing the area, then offered my images to the Sierra Club to help its efforts. Less than two months later, a few of those photographs illustrated a long article in The New York Times Sunday Magazine explaining the issues of the environmental battle. I’ll never know if it helped in the successful effort to get Mineral King into Sequoia National Park, but it certainly didn’t hurt (figure 18-9).

Developing a Personal Style

Photography students of all ages are justifiably concerned about developing a personal photographic style. As a workshop instructor, I am repeatedly asked for the means, the method, and the key to developing their personal style. My answer to these questions is always the same: don’t give it a second thought. (In fact, don’t give it a first thought!) A personal style, like stuff, happens. (There’s a better word than “stuff” in this context, but to keep this book on a higher plain, we’ll settle for “stuff.”)

It’s my contention that anyone consciously working to develop a personal style ends up with a self-conscious, forced, and false style. It won’t be natural. It won’t reflect you. Why not? Think of it this way: In life, there are people who develop self-conscious styles, people who aren’t themselves. We have names for such people: actors and actresses. It’s great when they’re on stage or in front of the cameras, but off stage, they can be themselves. They don’t have to pretend to be someone else.

You are you because of the way you look, the way you think, the way you talk, the way you move, the way you interact with others, etc. That’s you. You didn’t work at that. You didn’t think about being you. It just evolved. It happened. You simply ended up being the person you are. Nobody else can be you.

It’s the same photographically. Once you find the subject matter that really matters to you—that raises your passion to new levels—you’ll respond to it in your own unique way. You’ll see it your own unique way. You’ll interpret it your own unique way. You’ll photograph and print it with your personal stamp. Why? Because it really means something to you, and you simply can’t see or think about it in any other way. Beyond that, nobody else will see it, interpret it, post-process it, or print it the way you will.

![]() Once you find the subject matter that really matters to you—that raises your passion to new levels—you’ll respond to it in your own unique way. You’ll see it your own unique way. You’ll interpret it your own unique way. You’ll photograph and print it with your personal stamp.

Once you find the subject matter that really matters to you—that raises your passion to new levels—you’ll respond to it in your own unique way. You’ll see it your own unique way. You’ll interpret it your own unique way. You’ll photograph and print it with your personal stamp.

Of course, this implies that your technique as a photographer and printer allows you to do what you want to do. If your technical side is insufficient for the task, you’ll fall short. But while good technique is necessary to make your expression come to life, it’s not sufficient by itself. There must be the initial passion that ignites your fire—that starts your creative juices flowing. You have to find the subject matter that really matters. If you haven’t already identified what it is, keep your eye and mind open for it. When you discover it, you’ll know; you won’t have to think about it.

A corollary to the thought expressed above about seeing, interpreting, and printing things that truly excite you in your own way is that it frees you from the petty thinking that you have to guard your “secrets.” People with secrets invariably lack confidence, and generally for good reason. They fail to make a personal statement about anything, and underneath it all they recognize that failure (though they’re never honest enough to admit it . . . even to themselves). Photographers with ability and confidence share their thinking, their techniques, and their locations freely.

In my workshops, there are no secrets. My co-instructors freely share all their insights with the students, whether it’s locations, techniques, materials, thinking, etc. It’s far more rewarding to share than to be secretive. We share our discoveries with each other regularly. I learned the compensating developer procedure from the late Ray McSavaney, who taught workshops with me for many years. I learned about potassium ferricyanide reducing (bleaching) from Jay Dusard, who teaches workshops with me regularly. Don Kirby, with whom I’ve hiked and photographed for years, has greatly extended my understanding of masking. In recent years I’ve learned most of my digital photography through several friends, co-instructors, and students who have given me tips, tutorials, and valuable on-the-spot advice. In fact, much of my learning has taken place while I was teaching, proving that teaching and learning is truly a two-way street. I have always recognized that students have a lot of insight and knowledge, and I’ve often been the beneficiary of wonderful new ideas offered by my students.

Worthwhile photographers reason that if you learn some of their procedures, their ideas, their workflow, you may be able to eventually show them a wonderful photograph that benefited from one or more of those. Dedicated photographers enjoy not only making great photographs, but also seeing great photographs made by others. My list can go on and on, but my point is that people like these are the ones who are worthy of your company—but only if you are worthy of their company by sharing your discoveries with them.

Self-Critique, Interaction, and Study

Be your own toughest critic. That’s easier to say than do because it involves an extremely difficult transition from subjective response to objective analysis. Throughout the book, I’ve stressed the importance of allowing your emotional response and intuition to tell you what interests you. When you get excited about making an exposure in the field, you do so because you’re subjectively moved by something in front of you. You respond emotionally.

It’s just as important to be objective in analyzing your own effort spontaneously. You respond intuitively. But I’ve also stressed the importance of perfecting the imagery with non-spontaneous thinking about camera position, lenses, filters, exposure, etc. When you look at the resultant file or print days or weeks later, you must remove that subjective response and ask objectively and analytically, “Does the photograph alone convey my thoughts?” In essence, you must separate yourself from your personal involvement and ask if you’d honestly be inclined to stop and look at that photograph. That’s a tough transition. It’s a tough question. But it must be done if you want to analyze your work realistically. The subjective, emotional beginning provides your photographs with spark and life; the objective, analytical end assures that you present strong, meaningful work to others.

This is something you must do by yourself, but there is also more you can do with others. Seek out classes and workshops with good instructors who will push your development, and seek out peers with whom you can share your experiences while pushing one another.

Try to engage in a periodic critique of your own work and the work of others—not on a competitive basis, but on a mutually supportive basis. Again, this will stimulate your thought process and put you in regular contact with other photographers, other approaches, and other ways of thinking. There may be organizations or clubs in your area that promote such gatherings, and if not, see if you can start one.

Beware of organizations that sponsor contests. Contests are antithetical to art. Imagine a contest pitting Rembrandt against Van Gogh, Stieglitz against Strand, you against the next person. Who’s better? It’s a foolish question that deserves no answer. The only pertinent questions in art are, “Does it say something to me?” and “Does it show insight by either answering a question or posing one?” Contests are usually based on rules of composition. The only worthwhile rule is the one stated by Edward Weston: “Good composition is the strongest way of seeing.” Rules constrict creativity. In fact, creativity thrives when rules are broken.

Seek out knowledgeable people to critique your work. We all begin by having friends and relatives look at our work, but at some point you have to go to those who really know what they’re talking about and who are willing to say what they think. It may not be easy to take, but it’s the best way to boost your photographic development. Go back to your friends and relatives between bouts with those who know, and let them build up your shattered ego with praise. Then, when you’re ready, go back in the ring with the pros for another round.

Read about photography and photographers. Such books can open up new avenues of thought and stimulate new directions. Look at photographs and read what the critics have to say about them, but always take their words with a grain of salt. (A review of Reed Thomas’s exhibit in 1981 was quite positive, in general, except for some critical remarks about the images made from multiple negatives. The interesting thing was that Reed had never made a print from multiple negatives, but that didn’t slow down the critic who failed to look carefully enough to note that the multiple image effect came from window reflections and objects behind the windows!) Here and there, good critics can shed some illumination on photographs, and those reviews are useful for helping you analyze photographs yourself.

Photography classes and seminars can be very useful, depending on the instructor. Learn who the instructor is before wasting your time with a poor one. I feel strongly that the best way to learn photography (and perhaps many other arts, crafts, and even some academic subjects) is by old-fashioned apprenticeship. Apprenticeship is long outmoded, though it would be great if it could be brought back today. That approach allows you to learn directly from a master; no other approach can be as effective.

I could stand guilty of prejudice, but I feel that workshops are the best means of achieving photographic growth. Workshops are today’s closest thing to an apprenticeship. You can choose the photographer whose work you admire and take one or more workshops from him or her. You don’t have tests. You’re not graded on your performance, your attendance, your participation, or your attitude. You sign up because you want to learn. I got my start that way, and I see the intensity that develops during an uninterrupted week of interaction with other students and instructors. Nothing can be as informative as that exchange of information and viewpoints. Total, continuous immersion in photography for an extended period, without the distractions of everyday life, focuses the mind on photography. Nothing else intrudes. It’s the best possible method of acquiring maximum information and ideas in a minimum amount of time. You’ll improve your photographic techniques and define your photographic interests and goals.

Finally, always keep an open mind. Consider new methods and approaches. Seek to expand your own frontiers. Photography is a continuing, growing process. Keep growing. There’s always another valid approach, another new insight.

Keep searching.