18

A Lost Revolution

Sputnik moments cast long shadows.

—Teacher

Neuroscience came late to the schoolhouse. The fact that the brain—the one organ that is essential for learning—is not a prerequisite in teacher education programs makes very little sense. This omission speaks volumes. Teachers, in professional development courses, are quick to point out this gap in their preparation: “How come we don’t know about Reticular Activating System?” “It’s hard to believe I have never heard of amygdala hijack.” “I wish I had known 20 years ago about the cognitive revolution with alternatives for rewards and punishments.”

Indeed, many educators are surprised to learn about a cognitive revolution that, supposedly, occurred in 1956. Surprise turns to frustration, and not a little anger for some, when they realize that the knowledge contained in the so-called “revolution” could be beneficial in their classrooms. It was adopted by other academic entities—but not by educators.

The gathering of scientists occurred on the second day of a symposium organized by a “Special Interest Group” (SIG) in Information Theory at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (80). It was at this meeting that George Miller delivered his influential paper on the limitations of working memory (64). Looking back, he describes the moment of conception as an exhilarating time “when psychology, anthropology, and linguistics were redefining themselves, and computer science and neuroscience, as disciplines, were coming into existence.” (p. 141)

Without mentioning education per se, Miller admitted that it was a rather exclusive gathering. Referring to a paucity of resources, he suggested that many disciplines could not be invited to take part. Making no mention of the fact that education was not represented in the room that day, he did, however, acknowledge that, “Basic research in cognitive science has already had practical applications in such established fields as education and medicine.”

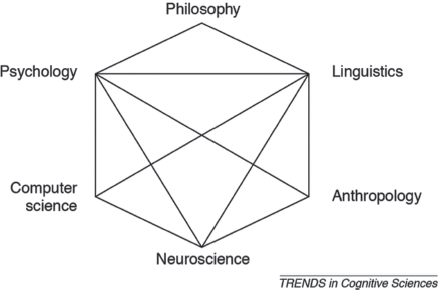

Cognitive Science

In 1956, educators were otherwise engaged. Schools were busy setting up systems that were designed to educate large numbers of children who were required to attend school in the US. Figure 18.1 describes a summary of the state of cognitive science in a succinct graphical representation prepared for the Sloan Foundation. In this diagram, interactive connections and emerging synergies were apparent. It was exciting to witness groundbreaking new perspectives that cross-disciplinary scholarship might deliver to emergent and established fields—psychology, philosophy, linguistics, neuroscience, and computer science. It’s impressive to explore synergies of erudite fields. The glaring gap was education. In an evolving cognitive world, there was no room for method, practice, or science of pedagogy. Already, academic scientists in other fields—notably psychology, linguistics, and computer science—embraced the cognitive methodologies and were quick to “liberate” their fields from radical behaviorism with its attendant limitations (29).

FIGURE 18.1 Education Was not Included in Cognitive Science, 1978

Scientists in the room that day had no idea that they were setting in motion any kind of revolution that would eventually be known as the “Cognitive Revolution.” They were interested merely in advancing the field of Information Theory by illuminating its connection with artificial intelligence. This is where a big pay-off for future collaborative research seemed to reside. As we listen to Miller summing up his conception of the future in cognitive science, we note the need to think about online learning, “teacherless” schools, and artificial intelligence in schools:

Miller’s theory had already outgrown Skinner. He shared Noam Chomsky’s and Herb Simon’s view that Skinner’s ideations were limited. They began by disagreeing with his claims that language resulted purely from external sources. For Miller, it was clear that “grammatical rules, which govern phrases and sentences are not behavior.” Chomsky was more direct. He forcefully belittled Skinnerian thinking by proclaiming:

As theoretical scientists in emerging and established fields abandoned Skinner’s theories in favor of a nuanced cognitive approach, they were deliberate about including mentalistic concepts. The brain had to integrate and explain behavioral data. Sadly, teachers missed out on this shift.

Consequence to Historical Change

That this cognitive revolution failed to arrive in the classroom might have something to do with the historical consequences of Sputnik (one year after SIG-IT-MIT), and the resultant existential focus on educational results and standards to ensure America’s dominant place, ahead of Russia, in the scientific world. In retrospect, it is ironic that the scientific community, which had managed to sidestep “ruthless reductionism” implied by stimulus-response behaviorism, failed to disseminate their new thinking and methods (including brain and mentalist processes) to teaching and learning. The fundamentals of the very science that launched the modern information-age were somehow obfuscated to learning institutions. Schools were hampered with a two-dimensional remnant of the previous industrial age. Stubborn adherence to an antiquated school system relegated new thinking to prescribed learning methods and practices that equated learning not to cognitive processing, but merely, to memory.

Notwithstanding the reason … missing the revolution has proved to be a heavy burden for teachers. Education systems mired themselves in a 19th-century framework that did not fit well with needs of accomplished learners in an information age (98). Consequently, teachers have struggled to understand unexpected behaviors from discontented children, with commensurate lack-luster outcomes in academic performance (115). Further compounding the damage, this failure inflicted long-term losses on America as a country, where entire lost generations of student potential failed to materialize (14, 116).

By missing the cognitive revolution, teachers missed scientific “breakthrough” discoveries in related fields—especially neuroscience—that were not only meaningful for classroom instruction, but essential knowledge for how children acquire language, how memory works, and how cognition elaborates information. Educators were at a loss for methods, practices and entire frameworks that would have changed fundamental mental models for application of motivation and understanding in the classroom. For instance, behavior, instead of being ‘bad’ or ‘good’, would be addressed as an important communication asset.

As learners, we missed Donald Hebb’s especially appropriate mental model about neurons that fire together wiring together (1960s). We missed Marion Diamond’s groundbreaking discoveries about implications for enriched environments and neural plasticity through cognitive rehearsal and myelination (1960s). Neural plasticity is so critical for learning and yet teachers missed out on the classroom relevance of nuance related to synaptic plasticity versus myelin plasticity. We missed Hebb’s critical understanding in relation to neuron assemblies (1960s). We missed Lomo’s exciting discoveries, which implicated synaptic modulation and long-term potentiation (1970s). This opened the door to enhancing children’s capacity to reach their true potential. If teachers didn’t hear about LTP until 2020, consider the lost generations of learners who were consigned to grow up in a different paradigm.

Instead, teachers were asked to double down on progressive punitive processes that carried an innate potential to fuel a robust school-to-prison pipeline (14). Knowing about Reticular Activating System, we are sure that maladaptive practices exacerbated children’s downward spiral. Could these negative learning events contribute to lives, which do not resemble potential? Teachers’ lack of awareness with regard to critical information about Miller’s Law is sure to cause cognitive overload for children who are struggling with formal schooling (117). Associated with cognitive load are issues pertaining to the size of working memory, the brain’s capacity to create new pathways, the brain’s ability to compensate for deficiencies, and the brain’s ability to build strong structures for success.

In addition, the educational system as a whole was deprived of important mental models that are brain-based, that resonate with children’s capacity to excel. Genetic and epigenetic factors are rarely in the classroom. Teachers cannot take into account a child’s autonomic nervous system reactivity, or their individual susceptibility because of neurobiological differences to social context. How many children failed to achieve their potential because they were too sensitive to survive in a stratification environment that propagates ‘social evaluative threat’ (SET) instead of inspired learning (108)?

This is not just a sad list of whining teachers who are disgruntled because they are not very successful at what they do. Data reported by the nonprofit public policy organization the Brookings Institute describe the real story. Brookings data confirm a very troubling picture of our children in education since the 1970s. Brookings experts conduct in-depth analyses that lead to new ideas for solving problems facing society at local, national, and global level. The current US educational crisis constitutes a local, national, and global calamity. This is what Brookings experts report:

Brookings is not a lone voice. International literacy and numeracy data from the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) attest to the same crisis. This revered body is an international organization committed to building better policies for better lives. Their Assessment of Adult Skills (AAS) confirms the troubling picture we paint of educational outcomes in the US by comparison with other first-world countries.

Comparing the oldest—those born from 1947 to 1957—to youngest cohorts—those born from 1988 to 1996, the US gains are especially weak.

The United States ranks dead last among 26 countries tested on math gains, and second to last on literacy gains across these generations. The countries which have made the largest math gains include South Korea, Slovenia, France, Poland, Finland, and the Netherlands (118). These data paint a clear, if disturbing, picture. Over the last 40 years, the United States has invested heavily in education with little to show for it. The result is a society with more inequality and less economic growth; a high price indeed (118).

Teacher Talk

Summary

A century lost, or so it seems! Hard lessons in the classroom and out! High stakes choices with consequences that are viewed in the rear-view mirror. Teachers bear an inordinate load to try to implement a system that is essentially “un-implementable.” We survived school; we should have thrived in school. Only time will tell. Will children who “actually” love to go to school do better than children who were coerced, bribed, and threatened with punishment if they didn’t excel in school?

Vocabulary

Cognitive Revolution, Mentalistic, Sputnik