Mary loves to shop. Easy access, limitless variety, easy payments—online connectivity has been a blessing both for consumers and online companies. Consumers like Mary are the engines of e-commerce, which has grown exponentially in many countries. Omnichannel business is a reality, and in poor countries, connectivity has meant bringing millions of disadvantaged people into the mainstream.

As people spend most of their lives fiddling with their connected devices, it was only natural that commerce moved there as well. People love to try out and buy new things. In the age of e-commerce, they get the means to do so at their finger tips. The long commute, the wait, and even the monotony of fiddling with online devices—all can be broken by browsing the huge variety of new products that are so easily accessible. Who can resist taking a look at the latest gadget or that little dress when it is so easy to do it? Today, thanks to easy connectivity, availability of payment gateways and systems to ease the buying process, e-commerce has grown considerably all over the globe. The Forrester Research Online Forecast (Sehgal 2013) says that e-commerce accounted for almost 9 percent of the $3.2 trillion total retail market in 2013 and is expected to grow at a compound annual growth rate of 10 percent between 2013 and 2018.

The phenomenon is not limited to the United States alone. The e-commerce sales in Western Europe is expected to grow at an even faster rate than in the United States in the next five years, from €112 billion in 2012 to €191 billion by 2017, representing a compound annual growth rate of 11 percent. In the UK, online retail already accounts for 13 percent of the total economy, and is expected to increase its share to 15 percent in 2017, according to the report. The IBM Retail 2020 (2012) report says that e-commerce is growing at five times the rate of traditional retailing and is expected to be over $500 billion within the decade.

Developing countries too are showing sizeable increase in online purchasing. China’s e-commerce market was estimated to be $210 billion in 2012, growing at a phenomenal compound annual growth rate of 120 percent since 2003, according to a report by McKinsey Global Institute (2013). The e-tail had a share of about 5 to 6 percent of total retail sales in 2012. Indian e-commerce has grown at a compounded annual growth rate of 30 percent since 2009, and is one of the fastest growing online markets. It is estimated to be $16 billion in 2015, growing to $50 billion by 2020, according to a report in Business Standard (2015).

Connected Devices and E-commerce

Digital devices have invaded our lives. People have come to love their smartphones. They see the phone as a device that helps them in many ways. This gives enormous opportunity to companies to plug in their content that interests users and leads them to their products and brands. E-commerce gets a huge boost from smartphone ubiquity.

Many factors have contributed to the growth of e-commerce. Among them are:

- A growing pool of technology-savvy population;

- Exponential growth of mobile phones and Internet penetration;

- Increased comfort with the use of electronic payments through credit and debit cards;

- Developing countries catching up in consumption with the rest of the world;

- Rapid spread of social media, increasing brand awareness;

- Offline stores selling online as well; and

- Micro payments, which help the poor to bank and transact.

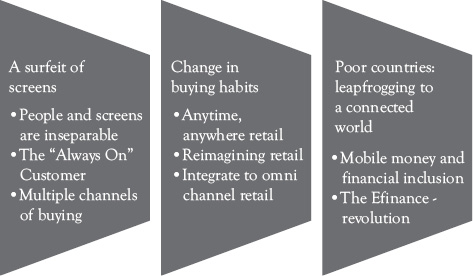

Market estimates by Gartner (2014) show that the devices are indeed becoming popular: Worldwide, smartphones have been selling more than basic feature phones since 2013. It says that the share is increasing as prices of smartphones drop. A screen in every hand has changed the buying habits and has helped developing countries to leapfrog into a connected world (Figure 2.1).

Figure 2.1 How the always-on customer is causing the push to omnichannel retail in the rich world and financial inclusion in the developing nations

A Surfeit of Screens

Screens have become ubiquitous. Research conducted by Vivaldi Partners (2014) shows that people in the United States use three connected devices every day, get online multiple times a day, and do so from at least three different locations. The study shows that 48 percent of consumers today are Always-On consumers who are obsessed with staying connected, leading to huge changes in human behavior. When asked what they would forgo for a year to be able to maintain Internet access, the study reports that:

- About 7 percent of U.S. consumers said they would forgo showering for a year;

- 21 percent said they would give up sex; and

- 73 percent said they would sacrifice alcohol.

This has resulted in a shift in media consumption patterns. A report by Nielsen, The Digital Consumer (2014) finds that consumption of TV content has increased because of the ability to watch time-shifted content. While watching TV, people also use their smartphones and tablets, using their devices as second-screens. This opens many avenues to deepen engagement with customers—an ad watched on TV can be immediately supplemented with information on the connected device, with the ability to order and pay at once.

Social media also helps e-commerce as it has become ingrained into the lives of consumers. By being present on such sites, a huge opportunity exists for the companies to increase their exposure with consumers during their consumer decision journeys. It is hardly a wonder that mobile retail is gaining momentum, with a huge majority of U.S. smartphone and tablet owners using a mobile device for shopping; developing countries, lagging basic telephony services, are leapfrogging to mobile transactions. Using a combination of media, including TV and online devices, companies find opportunities to reach customers at all times. Companies find that mobile commerce is giving them the power to reach out at all touch points.

The Forrester Research Online Retail Forecast from 2013 through 2018 shows that:

- Social media usage is now a part of daily lives of people—people visit social networks almost compulsively. Number of people using social media apps has increased, with people checking these sites while at work and even while in the bathroom.

- The average American household has high definition television (HDTVs) (83 percent), Internet-connected computers (80 percent), and smartphones (65 percent).

- Eighty-four percent of smartphone and tablet owners say they use their devices as second-screens while watching TV at the same time.

- On an average day, roughly one million Americans turn to Twitter to discuss TV.

Companies are leveraging these consumer habits and the surfeit of screens to drive online commerce. They attempt to understand and appeal to a generation growing up on digital devices and offer them value through products and omnichannel experiences. By all accounts, they are succeeding.

The Consumer Landscape

The change in buying habits over the last few decades has led to phenomenal changes in the consumer buying landscape. It is a change that had not been conceived by science fiction books or movies. Carrying their smartphones or other mobile devices, people check prices and shop at all times. Single day delivery is a reality. Drones deliver orders within a few hours in some areas. Customers who will not be home to take delivery can have their orders delivered to lockers located in subways which can be opened by a unique code sent to them by the retailer, and can simply collect their orders while walking through.

Companies and retailers are finding new ways to harness technology. They track customers through mobile devices, directing them to the nearest store in the neighborhood or delivering a discount coupon that they can use for their purchase, luring them into a store when they walk past it. Advertising too is done in a focused way, delivering tailor-made messages on their devices. Consumers scan the codes on products and in advertisements, and quickly connect with the company even while on the move. Restaurants enhance their environment with Wi-Fi access, getting free advertising when people share their location with others. Apparel retailers help people try out new clothes on virtual models and help them select what suits them best. Retailers offer online searches for products if they are not available in-store, promising to deliver them quickly if they are available in their inventory anywhere—store, warehouse, or factory.

This has given rise to anytime, anywhere retail.

Reimagining Retail

Digital-savvy consumers connect across all channels and touch points. As a result, consumers are empowered and informed. That is a big shift from the past and companies have to reinvent themselves to meet the needs of such customers. It is time to reimagine and reinvent retail.

Oracle’s survey (2011) of digital natives (people born after 1980) from the UK, Germany, and France revealed that the shopping experience of the future has to be connected, individualized, and always available. The results of the survey show that companies have to cater to discerning consumers who love to shop, with differentiated products, pricing, and services. Connected consumers interact with retailers when and how it suits them, and want their experience to be seamless across channels. Retailers must, therefore, optimize their operations for customer experience and operate in a connected full-time environment.

“The Internet has quickly become a very serious shopping alternative to traditional ‘brick and mortar’ retailers,” says the IBM Retail 2020 report. E-commerce sites are able to offer huge selection, customized offers, easy availability, and quick delivery, which appeals to people. The report makes several predictions about e-commerce.

- The digital generation: Young people born into the digital world will grow older and dominate shopping in the coming years.

- The hourglass effect: Consumers trade up and down, so that luxury retailers and those offering value do well. But the middle market is expected to shrink in the United States and in other mature markets, creating an hourglass effect. Stores catering to middle class customers have to create fresh value propositions.

- Growth in emerging markets: Since markets in developed countries are saturated, emerging markets like Brazil, China, and India will be the engines of economic growth. Brands have to make use of the great size of these markets.

- Excess retail space: Markets will witness excess retail space in many parts of the world. Online retail is going to cause problems for physical retail space, which has grown faster than retail sales growth.

- Integrated retail: Retail has to reinvent itself to combine the advantages of online with traditional business models, and vice versa.

- New ways of shopping: The mobile phone has become an accessory in shopping. People use it to find the location of physical stores, find the best prices, or locate friends who are in the vicinity, and so on. Companies use location-based services to offer localized and personalized offers. Sales persons will be able to do more than sales and become solution specialists by helping customers in solving their exact needs.

- The big four players: A set of four big online players will continue to shape online shopping experiences: Amazon, Google, Facebook, and Apple. Amazon dominates in e-commerce with variety, infrastructure investments in technology, and logistics. Google will continue to guide customers to merchants and product information sites, holding great influence about where consumers buy. It also offers services like Google Offers and Google Wallet. Facebook has a lot of data about its users and what they like. Converting this data to influence purchasing habits of its users will open a gold mine and it can become a sizable force in shaping and controlling future consumer behavior. Apple provides an ecosystem for customers with all online services and stores delivering customer experience.

Indeed, the world of brands and how they are sold has changed, posing challenges to the existing ways of doing business. Director of Commercial Experience at Adidas, Chris Aubrey, and David Judge (2012) of JudgeGill write, “Brands need to optimize the physical store so that it can drive operational efficiencies in terms of product range, capital costs and logistics, as well as deliver a consumer-focused experience that is on-brand and drives consumer preference.” Bricks-and-mortar offers retail a significant opportunity—to reimagine the role of the store so that it can rise to the challenges of connected customers. Physical retail channels have to be reinvented by companies so that they deliver on four fronts: experience, service, consumer-focused logistics, and integration.

Integrating the Shopping Experience

As a first step, companies have to discover the drivers of online purchases as also the factors that inhibit them. While consumers like the wide variety and ease of buying, there is also a lurking fear—at least in a segment of the population—of goods not matching up to expectations, security of payments, difficulties in getting after-sales service, or manufacturer’s guarantees. These are summed up in Table 2.1.

Table 2.1 Factors that encourage or inhibit online purchases

|

Factors leading to online purchases |

Factors inhibiting online purchases |

|

Ease and convenience |

Delivery of low-quality products |

|

Better prices, quick deliveries; availability |

Difficulty in returning products |

|

Huge choice and variety |

Difficulty in obtaining after-sales service—call centers are unresponsive |

|

Privacy |

Difficulty in getting manufacturer’s warranties |

|

Avoiding aggressive salesmen in physical stores |

Security issues in payments, risk of misuse of personal data, stealing of data by hackers |

|

Better information and payment terms, deals, and discounts |

Difficulty in returns and obtaining refunds |

|

Ability to source products globally |

Lack of ability to see and touch products |

Digital natives buy online comfortably, but others find it difficult to get over their inborn inhibitions. There is a need to understand all segments. Aljukhadar and Senecal (2011) divide online consumers into three categories which form three global segments:

- Basic communicators: Likely to consist of older people; these consumers use the Internet mainly to communicate via e-mail and look for information.

- Lurking shoppers: Consumers who employ the Internet to navigate and shop. Mostly this group consists of highly educated males or females.

- Social thrivers: People who use the Internet to interact with each other socially by means of chatting, blogging, video streaming, and downloading. Such people are most likely to be less than 35 years old and fall in the lowest income bracket.

Each segment has to be approached differently. Companies have to make efforts to help overcome the fears of the basic communicators. For lurking shoppers, they have to improve customer experience leading to branding and loyalty. For social thrivers, companies have to improve engagement through relevant messages and content, which leads them to brands.

Sorce, Perotti, and Widrick (2005) studied the buying behavior of younger and older online shoppers and their attitudes toward Internet shopping. They found that while older online shoppers search for significantly fewer products than their younger counterparts, they actually purchase as much as younger consumers. So, though older consumers were less likely to search for a product online, once they had done so, they were more likely to buy it online than younger shoppers. Most shoppers have four objectives for online shopping: convenience, information access, selection, and ability to control the shopping experience.

The key to online customers remains enhancement of customer experience using the above four elements. Integrated across channels, it leads companies to omnichannel retail.

Exhibit 2.1

Integrating Physical and Virtual Worlds: General Electric’s Direct Connect Program

The Always-On customer requires companies to integrate all channels. Distribution channels must merge with sales, service, and information channels to provide real-time information to customers. Companies understand this and integrate the information available online with their capabilities in physical supply chains for wide-ranging savings. This exhibit shows how General Electric (GE) was able to reduce costs through integrating channels in its white goods division.

Treacy and Wiersema (1995) describe how the company was able to integrate online channels to help reduce inventories and thereby heavy investments in distributing products. Traditionally, the business operated on the principle a loaded dealer is a loyal dealer, that is, if dealers have excess stock, they would be committed to sell it and would not be able to stock goods of anyone else.

However, this thinking was becoming irrelevant as retailing changed. Low-cost retailers gained a distinct advantage over GE dealers. In the 1980s, therefore, GE decided to transform itself and become a low-cost, no-hassle supplier to dealers. It abandoned the loaded dealer concept and decided to build operational efficiency instead. Dealers were connected to the company’s supply chains and depended on virtual inventory—a computer-based inventory system—and no longer had to stock excess stocks and incur carrying costs.

GE’s Direct Connect program helped link dealers to the company’s own inventory. Dealers were now able to access hundreds of models and show them as lying in their warehouses, though they did not have them. Customers could see and experience the few models that were available in stores and see the variations on computer terminals. The model selected by the customer is ordered on Direct Connect and immediately shipped by the company from the nearest warehouse.

In this way, the company reduced inventories across channels and integrated dealers into its own system. In turn, dealer information, such as customer data and movement of goods, was made available to the company in real time. The company saved distribution costs through the system, while the dealer operations also became more efficient. By linking the system to order processing and demand forecasting and production, the company operates to consumer demand rather than loading dealers. The company backed up the system by creating 10 warehouses that can deliver 90 percent of the orders in 24 hours.

The experience of GE’s Direct Connect program shows that companies can gain by:

- End-to-end integration of supply chains;

- Standardizing operations and systems; and

- Management systems that favor integrated and high-speed transactions.

Omnichannel Retail

Omnichannel retail has become a reality because people move across channels seamlessly. In omnichannel retail, all channels, including online and offline ones, track and entice customers. This is necessary because consumers do not distinguish between online and offline channels. A consumer will, for instance, see a hoarding and his mind will connect it with the store display or TV commercial, and in turn with previous experiences and store ambience seen earlier.

Integration of channels is, therefore, an evolutionary response to the changed environment. Physical stores face a threat from e-commerce, so they must use online channels to offer a seamless experience. Online companies, on the other hand, find that they must deliver a physical experience so as to deliver customer experience at all touch points.

That is why companies must combine their online and offline experiences. They must first connect various channels, and then go beyond connecting those channels, converging them with customer touch points. Though companies treat these activities as different departments, customers view them as one company, whether online, in-store, on a mobile device, tablet, or anything else. They want a multichannel experience with seamless interactions, with a availability. This gives rise to the opportunity to offer personalized promotions and interactions so as to engage the consumer.

To meet the expectations of the customer, companies exploit technology to expedite the shopping experience, optimize their operations, and develop multichannel strategies. Brick-and-mortar stores remain critical in the shopping experience of the future. Physical stores exhibit products and deliver great shopping experiences, while online services allow customers to explore the complete range, compare prices, and learn from others.

Physical retail channels have to deliver on four fronts: experience, service, consumer-focused logistics, and integration into omnichannel systems. Aubrey and Judge (2012) mention that the omnichannel approach is the new normal—companies have to adapt to a commercial landscape in which value-oriented and omnichannel consumers are in control. They have to absorb the higher costs related to the extending supply chains across channels.

Online retailers try to deliver a good offline experience, while brick-and-mortar retailers increase their reach through online offerings. Growth comes from two developments. First, as the use of smartphones and tablets spreads, consumers are spending more time online to explore products. Second, traditional retailers are increasing their online involvement.

Thus, omnichannel actually is a survival strategy: Threatened by the online onslaught, traditional retailers are left with no option but to follow their customers on the Internet. For example, the leading bricks-and-mortar chain, Macy’s, tracks customers by installing 24 tracking cookies on a visitor’s browser, according to MIT Technology Review (Regalado 2013). It combines other channels well: It uses TV advertising with a celebrity, Justin Bieber, who asks customers to download its mobile app, which guides them to stores. During shopping, the app is used by customers to scan the QR codes on products and to connect with the company. The chain of more than 500 Macy’s stores are used as distribution centers, from where online orders are shipped.

Companies such as Macy’s integrate offerings so as to provide convenience and seamless shopping experience through cross-channel delivery options such as click and collect or click and pick services. Retailers and consumers interact with each other online through mobiles, tablets, and kiosks, while in physical stores.

How companies are integrating channels to deliver a seamless customer experience is summarized in Table 2.2.

Table 2.2 Integration strategies used by online and offline merchants

|

Company category |

Integration strategy |

|

Online merchants |

Improve delivery systems Offline experiences and customer service Physical stores for display, trials, click and pick and click and collect |

|

Offline stores |

Provide detailed information about products online Salespersons help in-store search using tablets Take orders online and deliver from stores Real-time inventory tracking across stores Interactive boards and screens enabling customer engagement |

This phenomenon is not limited to the rich countries only. Across the world, people are using smartphones to research purchases, find stores, look for best prices, and make payments. It has emerged as an instrument of empowering people in poor countries, who can now spend and receive micro payments and conduct transactions through their mobile phones.

Developing Countries: Leapfrogging

to a Connected World

While consumers in developed economies see integration of channels and improved customer service through integration of channels, e-commerce is being ushered in by mobile phones through entirely different and unique ways in developing countries, changing the lives of the poor. For instance, The Economist reports that the poor are using them in innovative ways to increase their business. Beeping, or the practice of hanging up after a single ring, has become a free messaging system: Street hawkers assign special ring tones to different customers and become the means of placing orders.

E-commerce is being helped in such countries by the falling prices of smartphones. The average selling price of Android smartphones was $254 in 2014, and was expected to fall to $215 in 2018. Google launched Android One in 2014, which enables partner companies to sell smartphones for $105. In emerging markets, local manufacturers are able to offer smartphones that are less than $100; price tags of $50 are a reality in many parts of the world.

Perhaps never before has a technology penetrated so fast to the poor. It has given a boost to commerce, enabling even small traders to benefit from technology.

The way that e-commerce and mobile payments work with the poor is entirely different from the Western world, fulfilling a more important role. In the more developed countries, most people have bank accounts and the mobile phone serves as an additional payment channel. In emerging economies, it is being used to empower poor people who do not have bank accounts or access to formal banking. Since many developing countries have nonexistent or poorly developed financial infrastructure, transactions are done mostly in cash. The poor—because they live in remote areas or lack education—mostly remain outside the banking system. Low levels of financial inclusion condemn the poor to make use of informal systems, which have high interest and transaction costs. This poses a barrier for social and economic development.

Mobile money has helped financial inclusion of the poor in emerging countries. A growing number of people in remote areas are now using mobile phones for payments. One such innovation is M-Pesa, a mobile phone-based money payments service developed by Vodafone and launched by its Kenyan affiliate, Safaricom. M-Pesa helps people to make very small electronic payments and to store money using ordinary mobile phones. People use their phones to transfer funds to M-Pesa users and nonusers, pay bills, and purchase mobile airtime credit for a small, flat fee of 2 percent per transaction. The low fee has helped penetration among the poor and enabled them to get access to formal financial services that they lacked.

Mobile money systems such as M-Pesa enable people to use formal banking and financial services, freeing them from money lenders. It allows millions of people to get access to financial services cheaply and securely. In Kenya, for example, active bank accounts increased from 2.5 million in 2007 to more than 15 million in 2011. Unbanked consumers using the mobile banking service M-Pesa doubled between 2007 and 2009. They saved transaction costs of approximately three dollars per transaction; M-Pesa is being used not only for transactions but also for savings. More services are being added as people get access to better technology. These include financial services such as credit, insurance, merchant payments for goods and services purchased, governments payments, and to collect tax revenues.

It is estimated that M-Pesa transactions in Kenya outnumber the total number of worldwide transactions made by Western Union. In many countries, governments are allowing e-money and the operation of nonbank operators. Together with the success of electronic remittances, digital payments are leapfrogging the need for building costly formal banking structures. Similar systems like easypaisa, t-cash, and others have been launched in other countries, with varying degrees of success.

Mobile money helps people in emerging economies to:

- Make money transfers;

- Pay bills for utilities and services;

- Receive government payments such as social security payments, salaries, and pensions;

- Access banking services; and

- Purchase airtime.

Companies eye the market opportunities that technology opens up in emerging countries. They look at the sheer size of markets in Brazil, China, Africa, and India to sell their products. Brands are already entering these countries through online offerings.

More important, many countries are leapfrogging—that is, jumping to a new technology without going through intermediary technologies. Mobile phone technology, for instance, is available in many developing countries and areas where even landlines were not available. “By leapfrogging technologies like telephone and cable landlines, emerging markets will be able to access productivity-enhancing technologies for a tiny fraction of the cost,” explains (Ernst and Young, n.d).

The E-finance Revolution

E-finance is a revolution for poor countries. Evidence indicates financial inclusion is starting to happen. In many African countries, electronic cash and multipurpose cards help in savings and payments for customers who often do not even have formal bank accounts. Countries like Brazil, Estonia, and the Republic of Korea show that e-finance can be introduced quickly even where basic financial infrastructure is weak.

“The service has brought millions of people into the formal financial system, hobbled crime by substituting cash for pin-secured virtual accounts, and created tens of thousands of jobs,” writes Mutiga (2014).

Some developing countries show how leapfrogging has changed lives. In Zimbabwe, Botswana, Cote dÕIvoire, and Rwanda, wireless phone subscribers outnumber fixed-line users. Cambodia has a low per capita income, but the country has a high mobile telephone penetration, according to a report by the World Bank (Claessens, Glaessner, and Klingebiel 2001).

The initial fears of consumers to pay online have been overcome in many countries by higher security standards. People trust the

e-commerce sites that take responsibility for payments and refunds. E-commerce payments fall in the category of Card Not Present merchants, since customers do not swipe cards. Multiple verification systems and enhanced security standards have to be used to make online payments safe, and fight a constant battle to remain one step ahead of the hackers.

E-commerce is changing the way business is done. It has many faces: In the developed world, the use of big data defines anticipating and fulfilling customer needs. In emerging economies, it offers people, even those living in remote areas, to buy products and brands that they had no access to earlier. Also, in poor economies, as people get used to using online payment services, markets will leapfrog and mature into full-fledged e-commerce sooner rather than later.

There is little doubt that e-commerce is the future everywhere. How it evolves and how companies make use of opportunities globally remain to be seen. Innovative apps are waiting to be built and technologies continue to evolve and develop to take e-commerce to entirely new directions that we cannot imagine today.

To develop it further, businesses have to look at the characteristics of the connected consumers like Mary, their needs and motivations, and their ease in dealing with omnichannel buying in the next chapter.