Chapter 4

Work and the Dimensions of Energy

Some years back I sat down with the CEO of a mid‐sized technology company that had engaged my company to help with its stalled turnaround and its transition toward becoming a large company in a fast‐growing sector. I was directly involved in the engagement, playing the roles of executive coach and organizational advisor. My interviews with a number of company staff and executives provided the fodder for my analysis of the company's situation and problems. I was now with the CEO, whom I will call Mark, to give him my preliminary report and advice. He was particularly interested in what was stalling his turnaround progress so I focused on that.

“Mark,” I said, your company has been around for about 15 years and among your staff you have about 70 veteran employees who have been with the company most of that time. They know your products like no others and much of this knowledge exists only in their heads. Documentation is still pretty sparse, so they hold the keys to the kingdom. As I looked for areas of resistance to your turnaround efforts, I discovered that they informally formed a gang over the years that amassed tremendous power and exercised bully tactics when necessary to get what they wanted. This self‐serving strategy revolved around their own job security, compensation, and comfort. They've been operating covertly and effectively, protecting the status quo. They want you to fail so they can keep things the way they are, and your highly visible reputation for firing people every time something goes wrong is not helping. They're afraid and are circling the wagons.”

I named the gang the Underground Railroad and told Mark their attitude was that “CEOs come and go, but we stay. We are the real power in the company.” I advised him to cool his habit of making employee terminations public events and solve the root cause problems, which I outlined for him, without overly threatening the veterans. “Get your products documented, take your power back, and then rock that boat if you still need to.” Unfortunately, Mark didn't heed my advice, preferring his usual tactics over my suggestions. In response, the veterans dug in and the turnaround remained largely stalled. About six months later things caught up with Mark. The board removed him from his position and sold the company to a rival. It's never a good idea to underestimate people or to fail to adequately take them into account. In order to optimize any business, function, or change initiative, we must understand the energy that people bring to their work and strive to align it around common business goals.

The Dimensions of Energy in Work

Up to this point in this book, we have focused on the profound effect that enterprise elements can and do have on the way people interact in a business. They can promote effective interactions or they can promote conflict. Now we shift our focus to the work itself within the business. The enterprise elements that surround people are only part of the picture. As we discuss in this chapter, we, as people, bring things with us to our work that interact with the surrounding environment to determine the outcome of our work. This blending is the intersection of, and interaction between, the enterprise and the individual.

This blending of energies has an infinite number of possible recipes and outcomes. Throughout a business there are multiple people at any moment in time conducting or participating in work streams. Each work stream has an energetic makeup and outcome that contributes to the collective energy of the business. Ideally, we would like every single work stream to go well and contribute the maximum possible amount of positive energy to the enterprise. That being the case, first we need to understand the things that make up work so we can go about optimizing the work stream.

The Dimensions of Energy and Their Ingredients

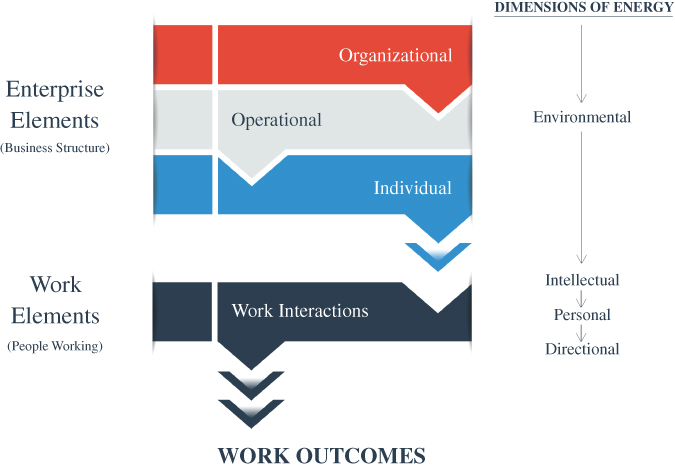

The Dimensions of Energy in Work model identifies and organizes the various factors that are involved in, and influence the outcome of, work. The model is based on careful observation of people at work and the things that influence them along the way. As shown in Table 4.1, there are four dimensions of energy in work. The first one, the Environmental dimension, is what surrounds and externally impacts the work. Its ingredients are the enterprise elements that have been the focus of this book so far. (Although it is true that what happens outside the walls of a business affects the work within it, it does so through the four dimensions described here, so we address the energy of those outside factors within this framework.) The other three dimensions, Intellectual, Personal and Directional, are things about the person doing the work. The ingredients of these dimensions are personal attributes. Taken together, the four dimensions of energy determine the work accomplished in any given work stream. The energy of work flows through these dimensions and, as we will see, the nature of the dimensions determines the nature of the work outcome and the energy associated with it. The four dimensions of energy, their ingredients, and their contributions to work are defined next.

Environmental Dimension

The Environmental dimension is what surrounds the person doing the work, and frames the work effort. It is composed of the business environment, which is made up of the organizational, operational, and individual enterprise elements. Together, these elements provide the field of play for doing work while also constraining it, sometimes appropriately (e.g., a well‐designed business process) and sometimes inappropriately (e.g., a poorly designed system). The environmental dimension can and does have a profound effect on how people work.

Table 4.1 The Dimensions of Energy in Work

| Work Dimension | Ingredients | Work Contribution |

| Environmental | Business Environment (i.e., the enterprise elements) | Framing |

| Intellectual | Clarity and Knowledge | Understanding |

| Personal | Intent, Attention, Engagement, Effort | Conducting |

| Directional | Skills and Behaviors | Navigating |

Intellectual Dimension

The Intellectual dimension relates to what the person knows and understands about the work. Its two ingredients are clarity and knowledge. Clarity is the degree of understanding around what the business/unit wants and what the person is being asked to do to support it. Knowledge is the person's intellectual capability and understanding associated with the work to be done.

Personal Dimension

The Personal dimension is about the character, attitude, and effort that people bring with them to conduct the work. It drives their personal experience with the work, which can be anything from joyful immersion to disgust and avoidance. It has four ingredients. Intent is what the people intend to do and not do regarding the work, which encompasses their goals and agendas, personal beliefs and attitudes, and personal positions regarding the work. Attention is how much attention the people give the particular work versus other things, and has a lot to do with how much they value and prioritize the work. Engagement is people's interaction and relationship with organizational elements, operational elements, and people who are needed to and/or are involved in doing the work. And effort is their degree of action and intensity in accomplishing the work. As the name implies, the personal dimension is about our own characteristics, motivations, and attitudes. That makes it powerful and worthy of self‐reflection as we do our individual work. Its partly hidden nature also makes the personal dimension more difficult to see and influence in other people.

Directional Dimension

Whereas the Environmental dimension is akin to the field of play, the Directional dimension relates to how the person doing the work navigates the field. The quality and impact of the navigation, and the choices made along the way, are driven by the skills and behaviors of the people doing the work. In particular, these are the skills and behaviors for doing the work and interacting with people and systems involved in the work.

The Big Picture

Figure 4.1 provides a big‐picture view of the flow of energy in work. It shows how the four dimensions of energy are involved in any work stream. The ingredients that make up these work streams cluster into two major parts: the enterprise elements, which surround us and frame our work, and the more personal work elements, which we bring with us. The figure also illustrates how work becomes multidimensional when others are involved. This complexity gives rise to the need for effective interactions and collaboration, which, of course, also affect work outcomes. (See chapter 5.) Overall, the figure illustrates the primary things and energies involved in work as a basis for both understanding and improving the conduct of work.

Figure 4.1 The Flow of Energy in Work

Next, we dive deeper into the dimensions of energy and some of their more important implications.

Implications of the Dimensions of Energy

The four dimensions of energy and their ingredients have a number of significant implications regarding work performance and management, talent management, change initiatives, enterprise design, performance improvement, and a host of other endeavors. We explore some of these implications here, starting with some general observations.

A Lot Going On

Taking the four dimensions of energy and their ingredients together, there is much more going on with work than meets the eye. When we recognize that every ingredient is constantly in play while a person is working, we begin to get a sense of the great swirl of energy that blends together to ultimately create the work outcome. No wonder managing ourselves and others can be difficult with all of that going on.

Good In, Good Out

The better the ingredients in the work stream, the better the outcome. Therefore, if we want to improve outcomes, we have to improve and align the work ingredients. We discussed the need for alignment among enterprise elements in the first three chapters. Now we extend that concept and need into the more personal elements of work. This concept becomes the basis for important performance improvement strategies for individuals, groups, and entire businesses.

Bad In, Bad Out

Deficiencies (misalignments) in any one or any combination of the ingredients in the work path will impede work progress and/or quality and/or speed. As is the case with enterprise elements, misalignment among personal work ingredients can lead to conflict, both internal and external. If we want to maximize work progress, quality, and speed, we need to be paying special attention to the ingredients with identified deficiencies that are not well aligned with the desired outcomes.

Overcoming Deficiencies and Obstacles

It is actually quite common for people in work streams to face deficiencies and misalignments in quite a few work ingredients while still producing an acceptable, albeit compromised, outcome. We learned this over the years teaching consulting skills to people in businesses. For example, we often observed significant dysfunction in the Environmental dimension that created pervasive conflict and made virtually any work much more difficult. In those organizations, the most valuable application of consulting skills was to help people get work done within their own dysfunctional companies and agencies. In other words, the new consulting skills and behaviors augmented the Directional dimension and gave people greater ability to navigate their work in a difficult environment.

Time and again these people overcame enterprise deficiencies to produce acceptable and, in many cases, very good work outcomes. Unfortunately, it took a great deal of energy to overcome the deficiencies, which made the businesses inefficient at best. The point is, overcoming obstacles and deficiencies is very common, very costly, and yet possible. The resilience of people at work can be quite impressive, but it comes with a price to them and the business.

Showstoppers

At the other end of the spectrum are the showstoppers, negative work ingredients that can stop a work stream or render it completely ineffective. Only one or a small handful of these ingredients can seriously impair work. This is true even if all of the other work ingredients are stellar and well aligned. For example, if a manager is part of a work effort that she does not agree with, she may simply never give it her attention. She may just let the effort die on the vine.

Showstoppers are often the stuff of personal agendas and office politics. However, they also occur more innocently. For example, someone simply may not have sufficient knowledge and understanding to complete the work. However they occur, showstoppers tend to be extremely wasteful. And in a political organization with a lot of conflict, they become weapons.

People who use showstoppers for their personal and political gain know intuitively that it takes a whole lot less energy to stop a show than it does to move it forward. This gives them considerable power and influence with relatively little investment of time and energy. Meanwhile, all of the energy that was invested in the work up until it was stopped is wasted; it produces nothing for the business.

Our Traditional Wisdom Isn't

As managers practicing surface‐level management, our typical inclination when we see work that isn't going well is to attribute the problem to the person or people doing the work. Unfortunately, we typically don't go much deeper than that. In truth, sometimes the people are the problem, and sometimes they aren't. When we understand that the problem can lie in any one or a combination of work dimensions, we see how limited we are by our traditional “wisdom” and antiquated management techniques.

Often our best people bring more to the table than others in the Directional, Intellectual, and Personal dimensions. They are better able to overcome obstacles, especially organizational dysfunction and politics, to produce acceptable work outcomes. Others run into trouble where the star performers overcome, and we judge them as if they are wrong for not being stars. That is not to say that we shouldn't move out chronically poor performers, but it suggests that there are often better ways to solve the real problems. For example, if we redesigned some dysfunctional organizational and operational elements, we could eliminate some major obstacles so that people don't have to be such star performers to get their work done, nor would they have to invest so much energy to overcome obstacles.

Training

When people have problems with their work, businesses often respond with training. Training can help the Directional dimension (interpersonal skills and behaviors) and the Intellectual dimension (hard/technical skills). Training can have a major impact on improving work, especially when the primary deficiencies are in the Directional and Intellectual dimensions. However, when other deficiencies are present and involved, they erode the impact of the training if they are not addressed. Unfortunately, this is often the case. Worse yet, when the primary deficiencies are outside of the Directional and Intellectual dimensions (i.e., when they are in the Environmental and/or Personal dimensions), training provides, at best, a coping mechanism.

Performance Improvement

Performance improvement is most often associated with improving the efficiency of a business process, which is a type of work stream. Usually the process itself is modified to improve the outcome. This is effective when the process, which lies in the Environmental dimension, is the primary deficiency. However, when there are other deficiencies and they are left unattended, a lean process may not help much. The positive impact of the process improvement is eroded. Perhaps there is a knowledge deficiency in the Intellectual dimension, or a resource shortfall in the Environmental dimension. Or perhaps there is a pervasive attitude problem in the Personal dimension that impedes the work. In any event, performance improvement needs to be approached in a holistic fashion that considers all work dimensions.

Change Management

There are countless books and articles on change management, but there is no model that always works. Furthermore, when we look at the fact that a large majority of change initiatives fail or significantly underperform, we see that, on average, change management models contribute to failure more often than to success. What are we missing?

The answer lies in the dimensions of work and the many involved ingredients. One of the biggest reasons change initiatives fail is that most address only a portion of the ingredients involved and leave the rest unattended. Anything that requires people to significantly change the way they work challenges their personal ecosystem, and addressing only part of the ingredients without recognizing the overall system often makes people feel like the business just doesn't get it and doesn't really care about its people. Therefore, managing change is, by nature, multifaceted.

Unfortunately, many companies hang their hats on good communication to drive change. They invest a lot of time and effort communicating with people to ensure that they have a good understanding of what will happen, what is expected of them, and how they will be affected. The degree of their understanding affects (to some extent) their performance in changing the way they work. However, there is more to work than the Intellectual dimension. While it is not practical to crawl into people's heads to affect every aspect of their work, the insights we gain through the lens of energy do suggest that we look under the hood of work and rethink our paradigms for managing change. We address this further in chapters 6 and 7.

In General

Many more implications derive from the dimensions of energy and their ingredients. We covered some general ones here. One common characteristic among all of the examples is that the model provides significant new insights into how and why things happen, and don't happen, in business. Work is a complex blend of many ingredients. Each ingredient has an effect on the work stream. If we are to improve work streams, we must improve and align the work ingredients. But there is another factor we must consider when analyzing and choosing the best way to improve work streams. That factor, which we cover in the next section, has to do with the interactions between work ingredients.

One Thing Affects Another

In our discussion of work so far, we have characterized individual work ingredients much like one might characterize ingredients of a cake. Each has a standalone impact when mixed with the other ingredients. For example, if you add more sugar, you will have a sweeter cake. The separate ingredients largely determine the taste of the cake overall. This is all true for work as well. However, for both work and cakes, it is also true, and quite important, that the ingredients interact and affect one another, similar to chemical reactions. While this does complicate things to some degree, it can also help guide us in our approach to improving work streams.

It Rolls Downhill

To introduce this concept, we will go back to the Alchemy Instruments example, both before and after the problems got fixed, and look at it from our new perspective of work. Specifically, we will focus on how ingredients in the environmental dimension affect those in the Personal dimension.

Again, here is a summary of the original problem.

Alchemy Instruments is a scientific instrument company that manufactures and sells high‐end electronic equipment to business clients across North America. It recently reorganized its sales force into two groups, the Product Group and the Regional Group. The Product Group is organized around the company's product lines, with subgroups for each line. Sales staff members in the group are instructed to sell their products to any potential client in the United States and Canada. The Regional Group is divided into six sales regions in North America. Those assigned to a region within the group are instructed to sell all of the company's products within their regions.

Although sales staff in each group were encouraged to work cooperatively with staff in the other group, problems began to surface in the field soon after the reorganization was completed. Members from both groups were calling on the same clients, cooperation and cross‐group support was at best a low priority, and the VPs of the two groups were at odds. The two groups became polarized and competitive. Less time was being spent on selling and more time was being spent competing with those in their own company.

The root cause problem turned out to be the wrong sales paradigm (individual selling), which was created by a host of ingredients in the environmental dimension, from the organizational structure to business processes to incentives. Instead, a new (team selling) paradigm was needed. The old paradigm caused a great deal of unintentional conflict between the Product Group and Regional Group and the people within the groups.

Now, with that background, how did all of these dysfunctional Environmental ingredients affect the Personal ingredients of an individual in one of the groups? The short answer is that they had a major impact on the personal ingredients. The longer answer lies in an analysis of the four ingredients in the Personal dimension: intent, attention, engagement, and effort. While there is certainly variance among people in the groups, this analysis focuses on the pervasive characteristics across the groups.

Intent

The SVP of Sales, who engineered the reorganization, wanted people from the Product Group and Regional Group to work together. He encouraged it. However, given the environmental circumstances, that was the last thing they wanted to do. They were incented to sell individually, not cooperatively. Furthermore, as the divide between the two groups widened and competition heated up, there was a disincentive to working with “those other guys.” The intent for the individuals in the groups was to do as much individual selling as possible and “may the best people and group win.”

Attention

People tend to put their attention on what is most important to them. In accordance with their intent, the salespeople put most of their attention on individual selling. Conversely, they paid little or no attention on doing things that would promote cooperative selling. They were not interested in building relationships with the other group, teaming up on sales calls, or doing much of anything that would take them away from their individual selling.

Engagement

Again, the SVP wanted people from the two groups to engage each other and work together to engage the clients. While there were some attempts to do this early on, people who tried it met with disappointing results. Remember the Product salesperson who stood up a Regional salesperson in a client meeting? The Product salesperson had “better” things to do (i.e., individual selling). A barrier formed between the groups and their people, and any attempts to engage the other group fell by the wayside. The only engagement that mattered was engagement with external clients.

Effort

Given the state of the other three Personal ingredients, you can imagine where people did and did not apply effort. They did apply effort to individual selling. Except for a short time following the reorganization, people did not apply effort to cooperative selling.

Now, given the state of the Personal ingredients among the salespeople involved, what were the chances that cooperative selling was going to work? It simply wasn't going to happen. The Environmental ingredients drove the behavior of the salespeople toward individual selling and created a breeding ground for conflict.

From this story, you can see that the ingredients in the Personal dimension were profoundly affected by those in the Environmental dimension. Personal ingredients that live within people contain receptors, sensing devices that are influenced by environmental conditions. While the environmental conditions provide the triggers for unintentional conflict, people ultimately choose how to react to those conditions. The more inclined people's Personal ingredients are toward conflict, the more difficult it is for them not to engage in conflict when triggered. In this story, we essentially rolled out the red carpet to conflict. The only chance to avoid it was for a person to mitigate this trigger/receptor relationship between the Environmental and Personal dimensions with a strong set of skills and behaviors in the Directional dimension—plus a lot of fortitude. Only then, with a great deal of effort, could someone navigate the sea of potential conflict.

A Success Story

Now we fast forward our story to its happy ending, when the real problems were fixed and cooperative selling was working. We will examine how the newly designed set of involved enterprise elements (Environmental ingredients) had a much different effect on the Personal ingredients.

The team selling paradigm had been fully implemented. This paradigm affected the same Environmental ingredients that were previously involved in the old paradigm. Now they were redesigned around the new operational concept, implemented with a coordinated plan, and adopted by the sales staff. Sales were up, and the mood was very upbeat. Let's look at how the four Personal ingredients were transformed due to the new influence from the redesigned Environmental ingredients.

Intent

The salespeople were now incented to work cooperatively in a team selling paradigm. They could no longer derive compensation from individual selling. Furthermore, they could see that team selling was working. Their intent now was to make team selling work better and better. They wanted relationships with those in the other group to be strong, as they could see how this helped them work better in teams. They wanted their own individual reputations to reflect that they were team players who could be counted on to do their part well as members of sales teams. They were still keenly interested in having strong client relationships, but they understood that no longer meant trying to do everything needed to make a sale and being the only point of contact in the company. They shared ideas and success stories with each other and set their sights on continuing to improve team selling performance.

Attention

Attention followed intent and was squarely on team selling.

Engagement

The salespeople engaged each other and the clients in new ways. Because relationships with those in the other groups (and their own) were important to them, they reached out frequently to initiate cooperation and engaged each other with mutual respect. They worked as teammates on the sales teams. They engaged clients now within the context of their individual roles on those teams.

Effort

Instead of spending time fighting and competing with those in the other group while protecting their individual selling turfs, salespeople focused their efforts on team selling and collaborative work. These efforts were rewarded with success and higher compensation.

What a difference in the work streams of the salespeople. This scenario illustrates how people change. In the business world where change is constant, it is essential to understand the inner workings of people and how they are affected by what is around them in the business. This story shows us that our change initiatives are not complete and sustainable until the four ingredients in the Personal dimension come into alignment with Environmental ingredients designed to bring about that change. The change is not complete until we have adequately changed the work streams of the individuals involved.

We need to use this understanding—that some work dimensions and ingredients affect others—to design our business transformation strategies, sequencing, and plans. It's all about energy and about how one thing affects another.

In the next section we look at how this new perspective can help us understand work stream issues at a deeper level so we can improve them through sustainable change.

Optimizing Work Streams

In order to optimize a work stream, we must first diagnose it to understand the work ingredients and their deficiencies/misalignments. We can then take action to minimize or eliminate deficiencies while aligning the involved work ingredients overall. However, not all work streams are created equal. There are three types of work streams. Each type has its own level, purpose, and optimization approach. The three work stream types are:

- Individual work stream. This is the work of an individual person. Improving an individual work stream is about improving the performance of a person in the business.

- Common work stream. A common work stream is one where multiple people do the same work. This is often a repeatable business process for individual work. Improving a common work stream is about improving the combined performance of everyone involved in a particular kind of work.

- Collective work stream. A collective work stream is a combination of different people performing different work streams in support of a larger common goal. Teams, in their many forms, are usually associated with collective work streams. A collective work stream is often summarized by a schedule with various tasks and timeframes. Improving a collective work stream is about improving the work of a team.

In this section we look at examples of each type of work stream and discuss strategies for diagnosing and optimizing them.

Individual Work Streams

Improving individual work streams is a common goal for us as individuals doing work as well as for managers with people whose work streams could use some improvement. Both target individuals and their performance. Either way the impact will be on a single person's work. While the impact of this improved energy within the overall enterprise may be relatively small, we must remember that every single person in the business can have a positive impact, and all of that energy adds up quickly. Even though individuals can't fix everything on their own due to the fact that they are surrounded by enterprise elements outside of their control, they can do a lot. Essentially they have control over the Directional, Intellectual, and Personal dimensions.

Improving your own work stream is somewhat easier than improving someone else's work stream. First, you are obviously privy to your Personal ingredients. With a degree of introspection, you can evaluate your intent and what drives it: goals/agendas, personal beliefs/attitudes, and personal positions about the work. You have direct access to that information. You are also aware of how much attention you give to the work stream, your tendencies toward engaging other people and things related to the work, and how much effort you put into it. In addition, you are largely in control of what you know (Intellectual dimension) and where you go (Directional dimension).

When we, as managers, embark on improving another person's work stream, we don't have that level of control, nor do we have a front‐row seat into the person's thoughts. We must use the indicators of the energy flowing through people and their work streams (i.e., their work characteristics and quality, behaviors, patterns, attitudes, verbal and written messages, body language, etc.). It is easier to be unbiased and objective when helping others improve their work streams. When considering our own work, our well‐honed defense mechanisms can kick in at any time and give us blind spots that don't help us improve. With this in mind, pairing a motivated individual with a manager or coach to develop their work streams is usually most effective.

Improving a work stream starts with diagnosing the problem(s). At one end of the spectrum, individual work stream diagnosis and improvement can be simple and fast; at the other end, it can be quite complex. We begin with some simple examples and then move toward complex ones.

Here are some simple examples of work streams gone awry that are quickly diagnosable:

- At the last executive team meeting, the president asked team members to create a one‐page report on the top five problems they are challenged with and to bring it to the next meeting to discuss. At the next meeting, everyone had their report except the Marketing SVP. When the president asked the SVP about it after the meeting, the SVP remarked that she had a lot of meetings last week and couldn't get to it. When the president asked the SVP what she thought of the assignment, the SVP said it was fine but she didn't see how it would help anything in her case. What was the problem ingredient on the work stream? A lack of Intent. The SVP probably never intended to complete the assignment in the first place due to her negative opinion of the work.

- A high school principal asked teachers to access some of the school's new online courses to get a feel for how they worked and to share any problems or issues at the next faculty meeting. The principal told the teachers that the person who led the implementation of the courses was available to show them how to navigate the system and encouraged them to meet with him before they reviewed individual courses to avoid getting lost. At the next meeting, the principal was surprised that only about half of the teachers had reviewed the courses. After discussing the matter, it turned out that almost every teacher who had completed the assignment sought out the help of the system implementer, while the teachers who didn't complete it neglected to seek help. A few tried to access the system on their own but gave up. What ingredient in the work stream was the problem? It was a lack of adequate Engagement. Both the implementer and the system needed to be engaged before a course review could occur.

- A skilled and experienced program manager known to have a high level of motivation has been assigned to manage five programs. Two of her programs were experiencing delays. When asked about it, the PM said that those two programs seemed less important than the other three, so she spent less time working on them. Where is the problem in the work streams for those two programs? Attention or, in this case, lack thereof. But there was no attitude problem that would suggest the PM didn't care or had some issue with the work. In this case, we must look a little deeper at the root cause of inadequate attention to the two programs. Clearly the PM didn't have enough time to go around. She was overassigned. This wasn't her problem to solve. It is a resource issue in the Environmental dimension. This story reminds us that we are not necessarily finished with our diagnosis when we identify the problems in the Personal dimension. To be thorough and accurate, always look deeper for interactions and the real cause and effect.

From these examples, you can see that by applying the Dimensions of Work model to a particular circumstance, we gain clarity on the what, why, and how that gives us a laser focus into understanding and solving the problem. The model is a framework for understanding the flow of energy in a work stream. We can see where energy is obstructed (e.g., lack of intent or adequate engagement) and when it is insufficient for the work to be done (e.g., resource shortages). And we can see that the energy in work dimensions (e.g., Environmental dimension) affects those in others (e.g., Personal dimension).

Even given the relative simplicity of these examples, it is amazing how often we misdiagnose problems. Faced with problems, managers often react with a general frustration that “these people are not doing what I want them to do.” Quite often their interventions are to repeat their orders, tell the person to fix the problem, or assign it to someone else. You can see from these examples that such general, uninformed interventions miss the mark. By looking at work streams through the lens of energy, we can avoid such mistakes and solve the real problems optimally.

Table 4.2 Work Stream Analysis Tool

| Work Dimension | Ingredients and Root Cause Deficiencies | Planned Improvements and Recommendations |

| Environmental | Involved Organizational Elements | |

| Involved Operational Elements | ||

| Involved Individual Elements | ||

| Intellectual | Clarity of Work Assignment | |

| Knowledge/Understanding of Work | ||

| Personal | Intent (goals/agendas, personal beliefs/attitudes, and personal positions) | |

| Attention | ||

| Engagement (with others and things related to the work) | ||

| Effort | ||

| Directional | Technical Skills and Behaviors | |

| Interpersonal Skills and Behaviors |

Individual work streams can and do become more complicated than the examples given for two reasons. First, when the work itself is complex, a work stream naturally becomes more complicated. Second, the work stream of even a simple task can become complicated when there are deficiencies and misalignments in several work ingredients. Either way, when things are complex, it helps to use the Work Stream Analysis Tool to diagnose the problems and plan the solutions. As shown in Table 4.2, the tool essentially lists the four dimensions of energy and their ingredients and provides space to list root cause deficiencies associated with specific ingredients as well as planned improvements and recommendations for each. To illustrate how to use this tool, we use the story of what initially seems like a simple work stream but is ultimately complex.

John Brown took a position as the VP of Operations for a midsize information services company. His position was responsible for all of the company's programs, of which there were four types: revenue producing (contracts), product development, system development, and internal change initiatives. To provide visibility up the chain, John's boss, the president, asked John to provide a monthly report with status on all of the active programs. The work stream we address in this story is the generation of the monthly report.

John pulled his directors together in a meeting to find out what systems and processes were in place to provide the information he needed for the report. The directors described a process where program managers provided their reports to their director and the directors compiled the information to generate reports for the VP. The VP then compiled those reports into the monthly operations report. That all sounded good and logical to John. He then asked the directors what information was provided in the reports. They said that each program report contained a description of activities/accomplishments/issues that occurred over the past month, planned activities for the upcoming month, and three status stoplights, which provided overall status for the program schedule, deliverables, and cost. Green meant everything was going as planned, or better. Yellow meant there were potential or emerging problems. And red meant there were significant issues (e.g., deliverable error, behind schedule, cost overrun).

John decided to go with that process to get information to develop his next monthly report. He asked his directors to send him their reports one week before his report was due. They agreed. However, the first time around, the reports dribbled in. John had to send out multiple reminders and was forced to start on his report before he had received even half of the needed information. The final reports came in one day before John's report was due, giving him little time to digest the information. He also noticed that every director used a different style and format for their reports; there was even more variance among program managers' reporting styles. Many described the details of their programs in great detail, and the directors didn't seem to be doing much to summarize or standardize the information. As a result, John ended up with over 100 pages of input.

John shuddered at the thought of delivering a 100‐page monthly report but didn't have much choice, at least for this first report. Although he was quickly coming up to speed on the business, he had much to learn. He didn't yet know enough about the business to differentiate important from less important program details. For now, he had to leave it all in. The stoplights were the only thing that provided an overall status summary, so he decided to emphasize those in the executive summary of his report.

John finished his report two days late and sent it to the president, who read the entire report. In a subsequent conversation, the president thanked John for the report and kindly mentioned that it was “full of information.” John said that he wanted to look at his process for creating the monthly report over the next few months to shorten it and make sure both he and the president were getting the information they needed while not having to wade through unnecessary details.

As John analyzed his work stream over the next few months and experienced life among the programs, he discovered a disturbing trend. Long‐term programs that had consistently reported green stoplights were suddenly reporting red in one or more categories as they neared the end of their program periods. Cost overruns were threatening John's profit goal, and schedule delays were causing problems with clients. John dug into the problem and analyzed the programs. He discovered that program managers did not have enough granular visibility into the status of their programs and realized that the problem began with how the typically year‐long programs were planned.

In the program plans, a big chunk of money (the program budget) was associated with a big chunk of work (all of the work to be done on the program). Consequently, program managers would color their cost stoplights green as long as they had money left in their budgets. When they neared the end of their programs and the money ran out before the work was done, they switched the stoplights to red. When this was reported in the monthly reports, managers were surprised all the way up the chain. John had little confidence that his monthly report was providing an accurate picture of project status, much less an early warning system. Furthermore, nobody could tell what parts of the program work were causing the cost overrun. The problems and resulting overruns could have occurred almost a year ago and only now were their impacts being revealed.

John knew that to solve the problem and give his program managers adequate visibility into status, the programs had to be planned in a more granular fashion. The planning process had to divide the work into smaller component pieces, with each piece being associated with the budget needed to do that work. That way, problems impacting budget could be identified early and dealt with then, when a difference could be made. John used the Work Stream Analysis Tool to document the deficiencies in the four dimensions of energy and identify planned improvements for each. Table 4.3 shows his analysis.

After completing his analysis, John marveled at the situation. The relatively simple monthly reporting work stream had uncovered a can of worms due primarily to the several dependencies his work stream had on Environmental ingredients. But John was grateful for the information and perspective his analysis provided. He knew that without making these changes, he could never be confident in his monthly report, much less in his ability to do his job effectively.

This work stream is a good example of why things that seem like they should be relatively easy, like a monthly report, can be difficult and frustrating. A surface‐level manager may react to this situation and his expectation of easy by putting pressure on the directors to stop the surprises or else. The directors would then roll that pressure and fear down to the program managers. The program managers' monthly reports might get even longer as they try to document anything that could go south so that, if it does, they can say it wasn't a surprise. There would be a lot more yellow in the stoplights, a cover‐your‐ass maneuver to be able to say “I warned you.” But none of this would really solve the problem. It would, however, cause a huge amount of conflict and blame.

The work stream in this story, which started out looking like a relatively simple individual one, is actually dependent on the other two types of work streams: common and collective. The individual work stream itself is relatively simple. Looking at John's analysis in Table 4.3, the individual work stream is focused on the VP refining the monthly operations report process and content while continuing to learn the business. The other ingredients in the analysis are related to the common and collective work streams that support the creation of the report. These additional work streams cannot be ignored because, as they say, garbage in, garbage out. That reality applies to energy and monthly reports. The VP has little choice but to lead the necessary changes in the common and collective work streams. Let's look at those in more detail.

Table 4.3 Monthly Reporting Work Stream Analysis

| Work Dimension | Ingredients and Deficiencies | Planned Improvements and Recommendations |

| Environmental | Involved Organizational Elements

|

|

Involved Operational Elements

|

|

|

| Environmental, Cont. | Involved Individual Elements

|

|

| Intellectual | Clarity of Work Assignment

|

|

Knowledge/Understanding of Work

|

|

|

| Personal | Intent (goals/agendas, personal beliefs/attitudes, personal positions)

|

|

Attention

|

||

Engagement (with others and things related to the work)

|

|

|

Effort

|

||

| Directional | Technical Skills and Behaviors

|

|

Interpersonal Skills and Behaviors

|

|

Common Work Streams

Common work streams are usually business processes, whether they are well designed and documented or just evolve naturally over time in the course of work. They involve multiple people doing the same thing. Usually the quality of the process design and its level of documentation determine how closely people follow a common process versus everybody doing it their own way. Sometimes the problem in a common work stream really is the process. But other times it is more than the process, or the problem may not even involve the process. That is why it is always important to evaluate all of the dimensions of energy in a work stream.

Our story includes three common work streams that provide inputs into the monthly operations report work stream: program planning, program management and oversight, and the program manager and director portions of the monthly reporting process. In each case there is a need and a goal for the people to do things the same way. That doesn't mean we want people to become nonthinking robots. It means we need a level of consistency in how people do these things in order to make the larger system work. Taken together, these three common work streams make up the bulk of what program managers and their directors do. Therefore, adjusting these processes is a big change for the group. It is, in fact, a culture change, which is why a culture shift is indicated in the analysis in Table 4.3. It also includes changing and bringing consistency to the way programs are planned, managed, and reported on; developing new capability and capacity among the program managers and directors, acquiring and implementing new scheduling technology, and developing new technical knowledge and expertise in the area of program management. To help promote the change, new (higher) performance expectations will be developed and communicated, and the VP will develop a deeper level of engagement with his staff.

What the table does not mention are the involved ingredients in the Intellectual, Personal, and Directional dimensions of the directors and program managers. There are two reasons for that. First, this book is not intended to be an exhaustive cookbook, and we don't want to bog down in details here. Second, the analysis is a good representation of a first pass done from the perspective of John, the VP in this story. John was understandably focused on his own Intellectual, Personal, and Directional dimensions.

What would ideally happen next, now that the existence of multiple common work streams has come to light, is that the Work Stream Analysis Tool would be applied separately to each common work stream, with ample attention to the more personal dimensions of energy in the work streams. These analyses would, of course, focus on the people who execute those work streams—the directors and program managers. This step becomes even more essential when a change of this magnitude is contemplated. Remember, we are not finished with our change until these personal ingredients are aligned with the Environmental ingredients and our desired work outcomes. Left unattended or partially addressed, the more personal dimensions of energy have a way of pulling things back to the way they were. Addressing these dimensions is often the difference between temporary and sustainable change.

Collective Work Streams

Collective work streams are becoming more and more common as businesses continue their shift toward the use of teams, especially cross‐functional teams, to accomplish complex business endeavors. The basic strategy is to build teams with talent representing the various functional disciplines needed to complete the project or program. The functional team members, either formally or informally, bring with them the business processes needed to do their work on the program. When these processes are well defined and documented, usually by functional departments or centers of excellence that own the disciplines, it is much easier to plan the work of a program, and the planning can be done in a much more granular fashion. Conversely, when the functional processes are undefined or poorly defined and documented, functional work on the program can become a mystery to the program manager, who is probably not an expert in each functional area. Under these circumstances, program plans tend to be high level and vague. That brings us back to our story.

Our VP, John Brown, recognized that the programs themselves were collective work streams. They were composed of cross‐functional experts performing a variety of work within the scope of the programs. The program plans were, unfortunately, vague. The program managers did the best they could, but the functional processes were not well defined or documented, so the work of the functional experts was largely a mystery. Furthermore, the work seemed to vary from person to person. Everybody had their own way of doing things. In short, the functional work streams that made up the programs were poorly defined, had a lot of variance, and were not sufficient to support the level of planning needed.

John flagged this problem in the essential producing processes section of his analysis. His discussions with the functional leaders further revealed that getting the processes better defined would be challenging. He knew that when the Personal dimension of energy among the functional experts was mapped out, it would reveal significant issues in the area of intent. Many of the leaders enjoyed the power of having the functional knowledge in their heads. From their perspective, it gave them value to the organization, which protected their jobs. Making that knowledge explicit for all to see would take that power away and make them feel vulnerable. Another obstacle was that people liked having the ability to do things their own way and perceived a consistent process as overly restrictive.

In spite of these obstacles, John knew that life would actually be better for the functional experts once his changes were implemented. Their work would be more effective, the teams would operate together much better, rework would drop, and errors would be avoided. Their new sense of value would come from the excellence of their work instead of the control of knowledge. The program managers would have the information they needed to create granular plans with better estimates and staff allocation. In executing those plans, the program managers would know when schedule, cost, or quality was threatened so they could take action immediately to resolve the problems. And, finally, John would have confidence that his monthly operations report was giving him and others visibility into the proactive program management that would make the programs highly successful. At last, John's individual work stream would be all it needed to be.

Although John knew that the effort to work with the functional departments to better document their processes would be substantial, he also knew it would pay big dividends. And, for the company this story is modeled after, it did.

Optimizing the Dimensions of Energy

In this chapter we took a deep dive into the nature of work. We viewed work as a flow through the four dimensions of energy—Environmental, Intellectual, Personal, and Directional—and defined the ingredients in each dimension. We saw that each dimension contributes importantly to the work but can also block or starve the overall flow of energy. We also explored how profoundly the energy of the Environmental dimension, which surrounds the people doing the work, can affect the Personal dimension in those people, both positively and negatively. And we parsed out the three types of work streams—individual, common, and collective—and used a story and a tool to illustrate how to approach optimizing each type.

Within all of this discussion, some significant insights emerged:

- The need to understand how work works. We took a deep dive into work because good work is what we want people to do in business. That sounds simple enough, but what is amazing is how limited our view of work has been. Now the moving parts in work have been revealed, giving us powerful new visibility, insight, and tools to optimize it.

- The contribution of people. While the role and impact of the Environmental dimension in work is huge, the role and impact of people is also huge. In the business of optimizing work, we should never look at one without looking at the other. In the end, people are needed to do the work. They need to be understood, managed well, and taken care of.

- The nature of change. The world is full of change initiatives and business transformations that don't stick. In the end, they create little sustainable change. Many have studied and written about this problem and have no doubt contributed wisdom to the matter. Most offer a list of reasons why initiatives fail. Unfortunately, however, the success needle hasn't moved much at all. One thing we've been missing is the fact that change is not complete or sustainable until the dimensions of energy and their ingredients are adequately aligned. We explore this idea further in chapters 6 and 7.

- Avoiding surface‐level management. Most leaders and managers learned surface‐level management in business school or on the job. It has been the norm in business for many years. As we explore the energy of business, we see just how limiting that has been. At the surface, where the view is limited, we misdiagnose problems, take actions that don't resolve the real problems, and hurt people and business performance in the process. And, until now, no one was the wiser. Now that the lens of energy has given us new wisdom and insight, we have an opportunity to move away from surface‐level management toward managing the energy of business.

In the next chapter we explore the final aspect of work, the interactions among people.