Chapter 5

Collaboration and Interpersonal Services

One of the most memorable collaboration experiences I have had occurred in 1999 when I was invited to participate in a knowledge management training session hosted by Kent Greenes, SAIC's newly minted chief knowledge officer. There were about 15 of us in attendance, all open and eager to taste the cutting edge of knowledge management. The environment was ideal for learning and collaboration, and the group had bonded during our morning activities. In the afternoon Kent divided us into three teams of five people each and explained the rules of our next activity. Each team would be given a box of small wooden blocks, some wooden skewers, rubber bands, and a small stuffed toy rabbit. A cute story that went along with all of this escapes me, but overall the object of the game was to use the materials to raise the rabbit as high off of the table as possible. As a test of strength, the structures were required to withstand an earthquake, which was to be simulated by dropping a phone book on the table next to the structures. There would be three rounds of play, and the team with the highest rabbit at the end of each won the round.

Kent assigned the teams to private rooms with no windows and started the clock on round one. My team struggled a bit in the beginning but then seemed to find its collaborative groove. We built a platform out of the blocks, fastened the skewers to the top of the platform using the rubber bands, and then mounted the rabbit on the tip of the highest skewer. It was our masterpiece. Kent called time and then he and another judge visited each room, simulating the earthquakes and measuring the heights of the rabbits. We came in second place, and were determined to improve in the next round. Kent brought the teams together into a neutral room and encouraged each team to ask the other teams questions about how they approached the activity. This gave my team some valuable insights, as the other two teams had thought of strategies and approaches that we hadn't. Armed with that new information, we jumped right in to round two, hitting our stride immediately. We again came in second place but, more important, all of the rabbits were substantially higher than they were in round one. What was strikingly clear was that the internal collaboration within each team, augmented with the cross‐group Q&A collaboration, was a powerful recipe for learning and innovation.

In preparation for the final round, Kent had the entire group visit each of the rooms to see each team's creation and ask questions about it. I found the ingenuity of all three teams to be quite impressive, each in its own way. After this show‐and‐tell, Kent sent us back to our rooms and started round three. Armed with the innovation secrets from the other two teams, my team went to work to put our rabbit into the stratosphere. Every aspect of our contraption had a purpose and strategy that emerged from all we had learned and experienced during the activity. In the end, our rabbit was over twice as high as it had been in the first round, and all three rabbits were inches from the ceiling. It was absolutely obvious and undeniable that the collaboration had produced something much greater than the sum of the parts. Granted, we were collaborative people in an ideal collaborative environment, but the activity showed us all what is possible when agendas and energies are aligned and people are unencumbered in their expressions of creativity. Although it is unrealistic to expect a home run from every business collaboration, our collective challenges suggest a relatively urgent need to move in that direction.

The Importance of Collaboration

We started this book by highlighting a growing need in the Fourth Industrial Revolution for people to become more effective at collaboration and interpersonal services. Based on our definition of collaboration in this chapter, all interpersonal services are a form of collaboration. In collaboration, people with common and aligned goals have a series of interactions that ideally lead them to the achievement of those goals. That's also the case with interpersonal services, the essence of which is mutually beneficial collaboration. For example, a sales interaction is a form of interpersonal services. The salesperson has a goal of selling something, making money, and pleasing customers. Customers have a goal of figuring out what product or service they need and buying it for a fair price. Thus, the salesperson's and the customer's goals are aligned. The collaborative interaction is about exploring options, identifying the best one, and then negotiating the price and terms of the deal that leaves both parties satisfied. The whole experience is a mutually beneficial collaboration. Therefore, improving our ability to collaborate also improves our abilities to provide interpersonal services.

We also discussed a variety of ways that organizational, operational, and individual elements, the Environmental dimension of energy, can and do affect the way people in business interact with one another. It is clear that if we want people in business to have productive interactions and to optimize the management of energy in the business, we must consider all of the enterprise elements and do what we can to optimize them. Nevertheless, at the end of the day, interactions are among people, and no matter how well or poorly the enterprise elements are designed, people have the power to make or break business interactions. Their positive interactions can grow shared space, and their negative interactions can erode it. Therefore, we turn our attention now toward these interactions and their relationship to collaboration.

Collaboration continues to be a big topic in business, and people generally understand the need for it. This is true probably because when collaboration doesn't exist, it's usually quite obvious. People are at odds, not on the same page, angry and frustrated, and not making much progress in the work at hand. Most observers would say, “We need more collaboration here!,” and they would be correct. Unfortunately, the way to accomplish collaboration can be elusive. This chapter shines some light on why that's the case and what we can do about it.

The Types of Collaboration

Research, literature, articles, and sales pitches on collaboration define and approach the topic in very different ways. Although there is some general agreement on the positive effects of collaboration that we are all looking for, there is certainly no agreement on what it is and how to accomplish it. Therefore, we start here with a short discussion on the different types of collaboration and some definitions to clarify our area of focus.

This truncated definition of collaboration from BusinessDictionary (2019) does a good job of summing up the many definitions out there:

Collaboration is a cooperative arrangement in which two or more people work jointly towards a common goal.

What we find, however, is that there are different methods and forums for working jointly. Specifically there are three primary types of collaboration: institutional, asynchronous, and dynamic.

Institutional collaboration is when the entities collaborating are businesses, educational institutions, and/or government agencies. While individuals are obviously involved, the key distinction here is that the interactions are primarily about group‐to‐group conversations and relationships.

The interactions associated with asynchronous collaborations do not occur at the same time, thus the term “asynchronous.” For example, people making contributions to a Google Doc may do so hours, days, weeks, or even months apart. Software developers may upload and download software modules to and from a common managed software repository throughout the project's life cycle. The primary characteristic of asynchronous collaboration is that responses to others' comments and input are seldom, if ever, immediate. Responses are separated by time. Another characteristic of asynchronous collaboration is that transactions run the gamut from transactional (e.g., here is my software module), to interpersonal (e.g., a thoughtful email reply to a sensitive subject). A final characteristic is that asynchronous collaboration often involves one or more collaboration tools.

With dynamic collaboration, interactions occur in real time—at the same time. For example, meetings (in person and virtual), phone conversations, and problem‐solving sessions involve real‐time interactions. These interactions tend to be reciprocal and more personal in nature. Responses to one another are immediate and in the moment.

A Focus on Dynamic Collaboration

Each type of collaboration is important, and all are growing more important each year as business continues its shift from independent and transactional work to shared and collaborative work. Our primary interests in this book are the interpersonal aspects of all three collaboration types. However, to help simplify the discussion, we'll focus primarily on dynamic collaboration, with the understanding that this material is relevant to the other two types to the degree that they involve the interpersonal dimension. Why focus on dynamic collaboration? Because dynamic collaboration, due to its real‐time nature, creates and is impacted by energy in a very immediate and significant way. It not only carries energy from the surrounding enterprise elements, which may or may not be in alignment, but it also has a dynamic relationship to the energy associated with the interactions themselves. This direct relationship can involve the creation of shared space or, on the other side of the equation, conflict. Either way, it involves the creation of an interactive momentum, which is all about energy.

In addition, dynamic collaboration permeates business affairs broadly. Consider the number of meetings, presentations, creative sessions, and customer conversations that occur every day in business. Whether dynamic collaboration is done well or poorly, it occurs at every level of the organization and in a variety of forums and formats. Therefore, improving dynamic collaboration capability in a business can have dramatic positive results with huge return on investment potential. In short, dynamic collaboration is a powerful lever of change worthy of our investment and attention. Furthermore, it is our future.

If we are to improve dynamic collaboration in our businesses, it is essential to clearly understand how it works. To do that, we must, as we have done so far in this book, look at and observe it from the perspective of energy.

The Collaboration Dynamic

The energy flow of collaboration is essentially a self‐adjusting system that can work to our advantage or disadvantage, depending on the nature of the interactions. It turns out that what is being adjusted within that system, the thing that can breathe life, creativity, and power into the collaboration, is shared space. This is not theory. The presence of shared space is something we have all felt and experienced. Consider this scenario:

You are meeting with a colleague to discuss an important business problem and work out a solution. The conversation is going well. You seem to have common ground and goals. You're working together toward those goals. It seems easy. You feel a connection and a camaraderie. You get the desired results—or even better!

This is shared space in action. The more it is present during an interaction, the easier things seem to go, and the better the outcome. Shared space is an energy, and therefore it is invisible to most people. However, its effects can be seen and felt, and we are all capable of creating it through our positive interactions. We are also capable of eroding shared space and creating conflict through our negative interactions. Our goal then is to have more of the positive and less of the negative.

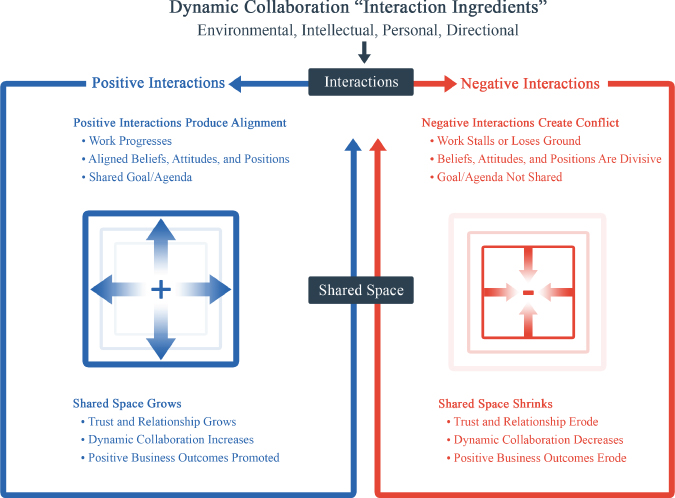

To do that, it is important to understand the system within which collaboration works so we can ultimately grow shared space and promote more effective collaborations. We call this system the Collaboration Dynamic. Figure 5.1 illustrates the Collaboration Dynamic at work.

Figure 5.1 The Collaboration Dynamic

The Dynamic Overview

The ingredients of work contained in the four dimensions of energy are also the ingredients involved in our interactions. Here we refer to them as the interaction ingredients. As is the case with work, a subset of ingredients are typically the primary players in a given interaction. The short story of the Collaboration Dynamic is that we start with a set of involved ingredients as if we are baking a cake. We, as people, bring the personal ingredients to the dance, and the rest exist around us in the business environment. When the interactions begin, these ingredients come into play as we allow them to. Some ingredients or combinations foster positive interactions that produce alignment and build shared space. Other combinations foster negative interactions that create conflict and erode shared space.

But that isn't the end of the story. We don't have collaborations for the sake of creating shared space. We have them to create positive desired outcomes with others. So here is the connection between shared space (or conflict at the other end of the spectrum) and outcomes. Shared space and conflict are not just the result of the interactions. Once created, they also become additional ingredients of the interaction. Shared space makes it easier to create more shared space, and the positive outcomes flow easily. Conflict breeds additional conflict and, without intervention, can drag the entire collaboration down a rat hole. The trick to collaborations is to stay ahead of the power curve. Doing so has a host of implications for how we can promote better collaborations. We will come back to that later. First, we'll walk through the Collaboration Dynamic in more detail and relate it to experiences we have all had in order to see it in action and understand its power.

Interaction Ingredients

As shown at the top of Figure 5.1, the dynamic begins with the interaction ingredients. Again, these ingredients are the things that surround and influence the interaction as well as the personal attributes that we bring with us. We view these ingredients now within the context of interactions.

At the top of the list are the Environmental ingredients. These are the enterprise elements at work—organizational, operational, and individual. As discussed earlier, the ways enterprise elements are designed and developed can have big impacts on the people in the business. These impacts, positive and negative, help set the stage for the interaction. For example, if the business has a collaborative culture, that ingredient will undoubtedly give the interaction a greater chance of success. If, in contrast, the culture is more about conflict and competition, that characteristic will likely reflect in a less successful interaction.

The Intellectual dimension includes clarity, the degree of understanding around what the business/unit wants the person to do, and knowledge—the person's degree of knowledge and understanding associated with the work to be done. Misunderstandings about what needs to be done or insufficient knowledge to perform the work will negatively impact the interaction. A strong Intellectual capability will support positive interactions, unless it is overdone. Too much intellect without the personal and directional capacity to utilize it properly can lead to unnecessary pontification and competition to be the smartest person in the room. Having a good balance is the key.

The Personal dimension is composed of goals and personal agendas, personal beliefs and attitudes, and personal positions regarding things or people related to the work. This is a critical dimension when it comes to interactions because the ingredients can have a lot of energy pointed in either the same or the opposite direction of collaboration. The ingredients of the Personal dimension are outlined below as they relate to the collaboration dynamic.

- Goals and personal agendas. We all have goals and personal agendas. There are two types. The first type, one that may or may not be present at the start of an interaction, is a shared goal. For example, if a scheduled meeting is about planning the next executive team offsite, we may come with a shared goal of building an agenda. Having a shared goal identified up front is clearly beneficial to the interaction. But this is not the case with every interaction. Perhaps someone didn't get the email or simply doesn't agree with the goal. That can throw a wrench into the conversation. The second type of goal and agenda is personal. It would be easier if we were all robots and could leave our personal goals and agendas at the door in favor of a common goal. Interactions would tend to go much better. However, as humans, it is unrealistic to expect personal goals and agendas to disappear during interactions. They will certainly be present, but as we discuss later, what becomes important is whether and how we allow our personal goals and agendas to affect our side of the interaction.

- Personal beliefs and attitudes. Again, we all have personal beliefs and attitudes, and we don't leave those at the door. If I am a consultant about to meet an executive who hates consultants, I am headed for a difficult conversation. The best I can hope for is to persuade the executive that I'm not like those other consultants and find a common interest that will help build rapport. If the executive likes to bring in consultants for help with specific needs, that orientation helps open the door for a strong collaboration.

- Personal positions. Personal positions are our positions on issues related to the conversation we are about to have. If we are to discuss where to move our facility, and I live on the south side of town, I may have a position that the new building should be on the south side of town. If you favor the north side of town, we have a significant challenge going into the interaction. Although that doesn't mean there is no hope for agreement, it will require effort and engagement on the part of both parties to find common ground.

The Directional dimension consists of the skills and behaviors that we have for, among other things, conducting and participating in collaborative interactions. They will be addressed in some detail later on, but suffice it to say that these skills and behaviors can have a major effect on the quality and outcome of our interactions. Regardless of the personal stuff we bring to the table, a strong set of skills and behaviors, along with a positive intent, can go a long way toward promoting a successful collaboration.

Fixed versus Flexible Ingredients

It is important to note the different nature of the various interaction ingredients, because some are more fixed than others. Specifically, those in the Environmental dimension (enterprise elements) and the Directional dimension (interaction skills and behaviors) are essentially fixed. While they will change over time, they will not change during the course of a conversation. Conversely, the ingredients in the Intellectual dimension (clarity and knowledge) and the Personal dimension (goals/agendas, personal beliefs and attitudes, and personal positions) are subject to change during the conversation. In successful collaborations, this movement is usually an indication of establishing greater alignment among those involved. Therefore, adjustments in the flexible interaction ingredients are a natural part of the Collaboration Dynamic. Each ingredient starts out one way but may be quite different by the end of the collaboration. That, in turn, becomes an important part of the ultimate outcome.

For example, let's say two members of Congress are collaborating on how to draft a particular bill. One is a Democrat and the other a Republican. They start off intellectually by each representing their party lines, which means they are intellectually at odds with each other. In the Personal dimension, each has a certain mistrust and distaste for the other because they are on the other side of the aisle. In spite of these initial divides, they share information and educate each other, which helps them find common ground on an approach for the bill. As their Intellectual alignment grows and they get to know each other through their interactions, they start to build a mutual respect that begins to neutralize the “other guy” posture they both started with. Before you know it, they are shaking hands in agreement and scheduling the next steps to move the bill forward. In the course of their successful collaboration, their Intellectual and Personal dimensions shifted in a unifying direction.

It's clear that some interaction ingredients morph and change during collaborations. The cake we start to bake isn't always the cake we end up baking because some of the ingredients change right there in the mixing bowl. And that can be one of the most beautiful and even magical things about a good collaboration! We have all seen and experienced it—a better outcome than we could imagine when we started.

Given the potential for the interaction ingredients to combine with detrimental effects, though, collaboration can be difficult and elusive. Nevertheless, the dynamic also reveals a number of clues about how to have good and productive interactions.

Interactions in the Collaboration Dynamic

Now that we clearly understand our interaction ingredients, let the collaboration begin. All dynamic collaborations are composed of a series of interactions among those involved. The nature of these interactions will, to a large extent, determine the outcome of the collaboration. At the extremes there are two types of interactions, positive interactions and negative interactions. As shown in Figure 5.1, positive interactions build alignment among those involved. You see the work progress more smoothly; the beliefs, attitudes, and positions of those involved become more aligned; and your shared goal and agenda become clarified and strengthened. Beneath the surface, shared space grows. There is greater trust and relationship, dynamic collaboration becomes easier, and positive business outcomes emerge.

At the other end of the spectrum, negative interactions create conflict. You see the work stalling or losing ground; the beliefs, attitudes, and positions of those involved become divisive; and the goal and agenda that was supposedly at the center of the collaboration is not being shared by all or perhaps by anybody. Looking more deeply, shared space shrinks. Trust and relationship erode, collaboration becomes more difficult, and business outcomes are headed in a negative direction.

As a practical matter, not every interaction falls at the positive or negative extreme. Those extremes are two ends of a continuum, and the quality of an interaction may fall anywhere in between. In other words, any interaction may embody both positive and negative characteristics. However, it is the sum of those characteristics that gives an interaction its prevailing direction.

Because collaborations are a series of interactions, and because some interactions may be positive and some may be negative, the energy of collaborations may actually switch back and forth between positive and negative. Thus, the Collaboration Dynamic is indeed dynamic.

In the next section we apply the Collaboration Dynamic to some example collaborations and explore the implications of “seeing” and understanding collaboration through the lens of energy.

Applying the Collaboration Dynamic

In the previous section we discussed how collaboration works with a detailed review of the Collaboration Dynamic model. In this section we use the model to examine examples and approaches for what we can do before and during collaborations to help optimize their outcomes. Then, in the following two sections, we identify and describe collaboration skills for one‐on‐one and group collaborations and discuss how we can improve our own skills and/or the skills of those in a group or an entire business.

The relevance and value of the Collaboration Dynamic model comes alive when we use it to better understand and improve actual collaborations. The Collaboration Dynamic does this in several ways:

How Collaboration Works

- The Collaboration Dynamic explains how collaboration works with a model that maps the factors involved, their interplay, and how both positive and negative outcomes may occur.

- It shows us concretely why we alone cannot ensure a successful collaboration but can promote one through our interactions.

Before a Collaboration

- The Collaboration Dynamic suggests approaches to setting the stage for a more effective collaboration.

During a Collaboration

- The Collaboration Dynamic provides a tool for evaluating why and how a collaboration we are in or are observing is working and/or not working.

- It suggests possible actions to improve a collaboration that is having challenges.

- It helps us understand our contributions (positive and negative), and the contributions of others, in collaborations.

Improving Collaboration Skills

- The Collaboration Dynamic provides a context for assessing our collaboration skills as a foundation for further development.

To illustrate how all of this works, we now apply the model to two specific collaborations.

The Spiraling‐Downward Collaboration

As discussed earlier, collaborations generally have a momentum that results in the growth or shrinkage of shared space. Shared space tends to promote even more shared space, and vice versa. We start with an example of a collaboration that gets off on the wrong foot and spirals downward from there, as if it were being pulled into a dark hole by a tractor beam. Here's the story.

A network technology company, Net Superior, experienced an embarrassing problem on one of its client implementation projects. The system had a major flaw that brought down the client's network for 24 hours during a critical time for the company. Similar problems had occurred on other Net Superior projects twice during the past six months, and the CEO was concerned about this repetitive pattern. He pulled the SVP of Professional Services, Mark Watson, and the chief technology officer, Steve McMahon, into his office to discuss the problem. Mark was responsible for all of the client implementation projects, and Steve's Technology Department provided IT resources to the projects. The CEO told Mark and Steve that they needed to work together to figure out the problem and make sure it wouldn't happen again.

Mark met with his project manager in charge of the troubled project to get her take on what went wrong. She told Mark that the problem was a network design issue caused by the tech lead assigned to her project. Separately, Steve met with the tech lead for a briefing on what happened. The tech lead told Steve that the project got behind schedule and the project manager made a decision to skip the design review. When Steve asked him why the project was behind schedule, the tech lead said that, at the time, he was assigned to four different projects and just couldn't keep up.

Mark and Steve were both somewhat relieved after their preparatory meetings. The prospect that the problem originated in their areas of responsibility had them fearing for their jobs. The CEO was taking heat from the board on this issue and was known to act swiftly and abruptly. Mark and Steve scheduled a meeting for the next day for the stated reason of sitting down to collaborate on understanding the problem and finding a suitable solution. Privately, however, both men had a primary goal of protecting themselves and their jobs by pushing to get their personal positions acknowledged and agreed to by the other guy. The stage was set.

The next day, Steve and Mark walked into the conference room and sat down on opposite sides of the table. They chatted briefly about the weather and their latest golf games. The nice talk ended there. Steve opened by saying he didn't have a lot of time and there was no need to discuss the problem. He knew what it was. Mark, who could already feel the blame, responded in kind: “I know what the problem is as well, a network design issue!” “Yes,” Steve said, “but it happened because your project manager cut corners and skipped the design review.” Mark responded loudly, “And she wouldn't have had to do that if your guy hadn't been so far behind schedule in his design work! How many projects did you have him assigned to?”

At this point the conversation was going downhill fast. Stepping back, Mark decided to take another tack. “Steve,” he said, “we're supposed to find a solution here and we can't even agree on the problem. Why don't we start over?” “Sure,” Steve replied. “As long as we can agree that the problem was your project manager's corner cutting.” “Really?” said Mark. “You can't see that because you haven't hired enough technology leads, the projects are shorthanded and falling behind schedule?” “Your people manage the schedules,” Steve stated defensively. Seeing the futility of the conversation, Mark pushed back from the table and said, “Well, I guess we will just have to agree to disagree.” With that, the “collaboration” was over.

This is obviously a fairly extreme example, but, unfortunately, it is not uncommon. Let's review what happened. How does the Collaboration Dynamic model help us understand why things went so poorly?

First and foremost, due to the circumstances and the nature of the interaction ingredients, the deck was stacked against this collaboration from the beginning. The stakes were high and fear was abundant. The business culture—the CEO's tendency and reputation for abrupt action—made this a job survival issue. There was little room for a common goal, as the survival of both men depended on making the other wrong. Both men came into the interaction with strong personal positions that were unlikely to change. Although it is possible under such conditions to pull out a successful collaboration, the odds are very low.

All of this played out as the real conversation began. Personal positions and agendas quickly took center stage. The conversation went immediately to conflict as Mark and Steve essentially fought each other for their jobs. That made them each other's enemy, so there was clearly no trust, relationship, or shared space. Mark made an attempt to rescue the collaboration when he suggested they start over. Unfortunately, the collaboration had too much negative momentum for that to work. Steve held onto his position, and Mark could see that any real collaboration was futile.

Steve and Mark remained in their positions, feuding from that point on. The CEO never figured out what the problems were because both men had plausible stories. He didn't manage the energy, he tried to manage the personalities. He kept trying to get the men to work things out. Ironically, it was the CEO who could have done more than anyone else in the story to promote a good collaboration and solve the real problems. To show how that would work, let's rerun the story with some modifications to the interaction ingredients and the interactions themselves.

The Truly Effective Collaboration

In this version of the story, we modify one collaboration ingredient, the company culture and the CEO's tendency to blame and create an environment of fear. Here we endow our CEO with a deeper understanding of how things work, a desire to get to the bottom of the real problems, and a stated position that it is OK to make mistakes occasionally as long as you learn from them and don't make the same mistakes again. When he pulled Mark and Steve into his office and asked them to collaborate, he made all of this abundantly clear. Mark and Steve knew that even if the problem originated in their areas, they would be OK as long as they fixed it. This launched a collaboration that had every chance of success.

What Mark and Steve heard from their people about the problem was the same as in the first version of this story. Mark's implementation project manager told him that the problem was a network design issue caused by the tech lead assigned to her project. Steve was told by his tech lead that the project got behind schedule and the project manager made a decision to skip the design review. When Steve asked his tech lead why the project was behind schedule, he said that, at the time, he was assigned to four different projects and just couldn't keep up. At that point Steve could see there were problems on both sides of the fence and that his insufficient supply of tech leads triggered the project manager's decision to omit the design review, a mistake on her part.

When Mark and Steve scheduled a meeting for the next day to collaborate on understanding the problem and finding a suitable solution, they had no hidden agendas. Their goal truly was to solve the problem together. Steve and Mark walked into the conference room and sat down at a corner of the table. After exchanging pleasantries and a few laughs, they got down to business. Mark opened by saying that his project manager told him the problem was a network design issue caused by a mistake on the part of the tech lead. But he qualified it by adding “With that said, I am not sure I have all of the information here, and I'd like to hear what you know.” Steve replied that he received some information from his tech lead that indicates the cause of the network design issue was multifaceted. With a generous demeanor, Steve said that he believed the problem started because his tech lead was overassigned and fell behind on his work on the problem project. The project manager then decided to cut out the design review to make up lost time on the project schedule, an unfortunate decision.

Mark thanked Steve for his research and analysis. He told Steve that while he knew a design flaw was involved, he did not know the circumstances around it. Steve commented that he had been aware of the need for more tech leads and that he was having trouble recruiting for those positions. Mark admitted that his project manager should have never cut a design review and that her authority as a project manager did not include omitting essential process steps. Steve agreed and replied, “It seems we now have a good understanding of the problems. Why don't we talk about how we will correct them and make sure they never happen again?” Mark replied, “That sounds good to me.”

Steve said that, first and foremost, he would work with HR to engage an outside recruiting firm to fill the open tech lead positions. “That will solve my problem right now,” he said, “but it's not enough to ensure that resource shortages won't occur in the future. I need some kind of a heads‐up warning system that will help me know, with as much advance notice as possible, that we are headed for shortages in a given area of expertise.” Mark said, “I can put in place a process whereby my project managers notify me if they are experiencing shortages on their projects, and then I can pass that information to you.” Steve liked the idea and told Mark he appreciated his offer to do that. Steve added, “But that still doesn't give me much advance notice, certainly not enough time to recruit new staff. While I think we should do it, I think what we really need is a capacity management system that looks six to twelve months out at our resource needs on the projects and translates that into needed headcount in the various functional areas.” Mark said, “That's a great idea! We can propose that as a new improvement initiative.” Steve agreed.

Mark next said that he would need to clarify protocols for his project managers on what they could and could not do on their projects. For simplicity, Steve suggested Mark could make a rule that the managers could not ask or pressure functional experts to cut corners on defined and approved functional processes, like design reviews. Mark agreed and said he would include that. He added that he would launch the newly refined protocols with training and communication sessions in his group. Steve liked the idea and suggested his people attend as well. Both men agreed.

Mark said, “Let me try to sum this all up and you tell me if I miss anything. You are going to work with HR to engage a recruiting firm and get your vacancies filled. I will implement a process that will notify me, and then you, when resource shortfalls occur on the projects. And we will both meet with the executive team and propose a new initiative to develop a capacity management system as soon as possible. I will clarify protocols for the project managers and roll out training and communication sessions that my people and yours will attend. Does that sound right?” “Absolutely!” Steve replied. “Let's go tell the boss we figured it out!” Both men felt relieved and energized. They shook hands and went to see the CEO.

This was a great collaboration, a far cry from the first round. The story illustrates some central points about collaboration.

- Leadership matters. The only difference in the starting ingredients between the first and second versions of the story was the style and position of the CEO. In the first case, he instilled a culture of fear and blame, which strongly influenced the personal agendas and positions of both men. In the second case, he fostered a culture of excellence and collaboration, which encouraged and motivated both men to hold the common goal—understanding, resolution, and prevention—as their personal goal. That made all the difference in getting the collaboration off on the right track and keeping it there.

- Clarification of knowledge and understanding. As discussed above in the description of the Collaboration Dynamic, some interaction ingredients are fixed while others are subject to change during the collaboration. The knowledge and understanding of the problem's root cause and solution grew throughout the collaboration. In particular, Mark's initial understanding, which was limited to the existence of a design flaw, expanded quickly as Steven explained the two factors that caused the flaw.

- Changing intent. Similar to the expansion of knowledge and understanding, Mark's intent changed during the interaction. He started with an intent and expectation that he and Steve would be focused on the actions of the technology lead and how to prevent people in that role from making design mistakes. As the collaboration proceeded, his intent changed as he realized there were multiple root cause issues to resolve.

- Shared space. You can see how shared space is reflected in virtually every interaction within the collaboration—both the creation of shared space and the boost that the existence of shared space gives the collaboration. On the side of creating shared space, Mark and Steve choose their words carefully out of mutual respect, limited their assumptions and stayed open, listened to each other and made remarks that were additive to the collaboration. Regarding the boost from shared space, you can see and feel the collaborative momentum build as the men reached a common understanding of the problems and made a string of agreements on what to do about them. The men were literally joyful at the end, and they created a beautiful business outcome that met, and probably exceeded, their goal.

As we compare and contrast these two stories, we recognize that the quality and nature of many collaborations fall between these two extreme examples. Many can go in either direction and may even flip back and forth between positive and negative. Some collaborations are saddled with issues in the Environmental and Personal dimensions, yet people can and do find ways to overcome them and achieve good business outcomes. To what do we attribute this ability to overcome adversity? Most often it is due to the power of the Directional dimension of energy.

The Power of the Directional Dimension of Energy

The ingredients of the Directional dimension of energy are the skills and behaviors that allow people in business to conduct work and collaborate. The dimension has much to do with a person's ability to create shared space while navigating obstacles and overcoming negative energy. This realization became abundantly clear after our many years of teaching consulting skills to professionals across industries. Teaching people things like empathy, how to consider the preferences and characteristics of other people, having good conversations, and building alignment within groups is all about navigating work and collaborating with powerful energy in the Directional dimension.

The many HR groups we have worked with over the years are good examples of how developing the Directional dimension can make all the difference. A popular trend in HR is to help what you might call traditional HR professionals who are used to a more transactional style of work become trusted HR business partners. HR business partners are typically assigned to a line manager and tasked with learning their part of the business and serving as a focal point for the more strategic aspects of HR. Although they may not articulate it this way, line managers think of these HR business partners as partners only if they understand their business, know their people, and, perhaps most important, have the ability to navigate complex interactions and business solutions. Line managers quickly grow tired when they are the only ones on their team who seems to be navigating complex work and collaborations. Line managers welcome skilled HR business partners who can take some of the load off.

There are many more examples in business where Directional skills and behaviors make the difference between a trusted business partner with great value and an order taker. That's why training in collaboration skills should focus on the Directional dimension with an eye toward overcoming obstacles and negative energy in the other dimensions.

We turn now to a discussion of collaboration skills, first for one‐on‐one collaborations and then for group collaborations.

One‐on‐One Collaboration

Effectively working one on one with others and providing interpersonal services ultimately boils down to the quality of our interactions. In general, if the interactions go well, the collaboration goes well. If the collaboration goes well, the work at hand gets accomplished and the stage is set for additional positive collaborations with that person. In contrast, if a conversation goes poorly, work is impeded, conflict often occurs, and future interactions with that person are burdened by the negative experience. The goal, then, is for our individual interactions and collaborations to go well. While this goal is absolutely realistic, it is formidable because there are so many ways to derail a conversation that was intended to be collaborative. We often feel an energetic shift and perceive negative cues in ourselves and others when our conversations derail. Here are some reactions to common derailers.

- You don't understand me. I don't feel like you know or care about me and my needs here.

- We don't seem to have common ground. I see that you have your own agenda.

- You talk at me, not with me.

- You seem to talk from a script, with little or no reaction to what I say.

- You tried to bully me.

- You only care about having the right answer and being the smartest person in the room. You don't budge from that role. Often I want something different or more than that.

- I see that you're trying to influence me, but it doesn't seem very relevant to me and my situation.

- I don't trust you.

- I'm not sure if I trust you.

- You don't seem to be aware of your impact on me or other people.

The question becomes this: How do we avoid such derailers and instead interact in ways that promote positive and effective collaborations? Here are some examples of reactions to the “positive” side of the collaboration equation.

- I felt like you understood me and my needs.

- You seemed to take my needs into consideration as much as your own.

- You are a good listener.

- You made me feel appreciated and valued.

- You built me up rather than shooting me down.

- The more we talked, the more I felt comfortable with and trusted you.

- I feel like we connected in our unspoken communication.

Each of these positive reactions is an indicator that we created shared space during the collaboration. We create shared space with another person when we focus on the bigger picture and the common good we can create together, not just on our own agendas. But how do we build and monitor shared space throughout the collaboration? That takes us back to the Directional dimension of energy.

Building Shared Space with Others

Some people intuitively know how to build shared space with another person during a collaboration, even if they aren't familiar with the shared space concept or term. However, if you ask them to tell you how they do it, you are likely to get a fairly general, nonspecific response. The reason for this general response is that it is difficult to describe what is often a very complex interplay. We need a way to bring it to the surface and make it explicit. In this section we use the Dimensions of Energy Model to help explain what goes on in a typical collaboration so that we can first understand and then use the model to help people collaborate more effectively. As you will see, there is both an art and a science to collaboration.

Building shared space during a collaboration requires careful communication that considers all four dimensions of energy, Environmental, Intellectual, Personal, and Directional. However, some dimensions require more focus than others. Because they are subject to change during the collaboration, we must pay particular attention to the Intellectual and Personal dimensions. Environmental factors are fixed during collaborations. Although they can clearly create obstacles and negative energy that impact interactions, or vice versa, they generally do that through the Intellectual and Personal dimensions in people. How do we keep an eye on these energies, process their meaning, and respond accordingly? We do this through the Directional dimension.

The trick in one‐on‐one collaborations is to navigate the creation of shared space from the Directional dimension to promote a co‐creation that modifies Intellectual and Personal ingredients in one or both people. Take the effective collaboration story with Mark and Steve, for example. During the collaboration, both men made Intellectual adjustments as their interactions revealed a deeper understanding of the problem and identified the components of the solution. Similarly, the Personal dimensions of both men changed as they solidified a common intent to implement their agreed‐upon solutions. Because of positive Environmental factors (i.e., the CEO's creation of a collaborative culture), both Mark and Steve were motivated to do their part in navigating the collaboration. Thus, a characteristic of effective collaborations is that Intellectual and Personal factors come into alignment.

Strong collaborators who are able to build such alignment have well‐developed and powerful Directional dimensions. These dimensions have two primary parts. The first part is the Observer. As its name implies, the Observer observes everything going on in the interaction and is aware of the surrounding environment. The Observer monitors the status and direction of the conversation, including the buildup or erosion of shared space. Observers also pay close attention to the Intellectual and Personal dimensions in others and themselves. The ability to observe ourselves means Observers have a degree of independence from the other dimensions, a very important characteristic.

The second part of the Directional dimension is our Guide. Whereas our Observer watches passively without judgment, our Guide processes the information and decides how to respond. In deciding how to respond, our Guide considers input from our Intellectual and Personal dimensions, and from those of the other person, and decides what should be represented in the next response. For example, my Personal dimension may be chattering away with “I don't like that guy, and his tie doesn't match his socks.” If my Guide is reasonably well developed, it would likely filter that and not let it influence my next response. Similarly, if my Intellectual dimension is screaming “That is a stupid idea!,” my Guide would not filter it but would be much more diplomatic in the presentation of that in my response, especially if my Observer was picking up that this guy really likes his idea.

Like our Observers, our Guides have a degree of independence from the other dimensions. The level of a person's independence in their Directional dimension has a lot to do with how well they are able to collaborate. For example, if I have little independence, I will have little ability to filter my personal agenda and hold it lightly in favor of a common collaboration goal. Conversely, if I have a high degree of independence, I can choose not to engage in conflict triggered by something in the Environmental dimension. Independence in the Directional dimension is a discipline that comes through awareness, practice, and experience. This independence is not about us becoming cold and machinelike. To the contrary, it is about bringing the best of our human elements to the table while avoiding those that would unnecessarily damage the collaboration. It is about building shared space, achieving business outcomes, and effectively playing our role as people.

Some people who meditate practice their ability to move into what is called the third person, a place of detachment where they are able to passively observe the chatter of their minds without engaging it. Being in the third person is quite similar to the independence and detachment ideally present in the Directional dimension. Thus, those who meditate may feel that the Directional dimension is familiar and may find that collaboration comes more naturally.

Essential Collaboration Skills

What are the essential skills and behaviors that make up the Directional dimension? What skills are needed for navigating collaborations and creating Intellectual and Personal alignment with others? While many skills may fall within the umbrella of collaboration, we focus here on the essential skills and behaviors. We can boil that down to a relatively simple recipe: Me, You, and Us. These are the basic ingredients of any interaction, so it makes sense that the essential skills fall in these three areas. Here is a summary of essential collaboration skills, which all fall into the Directional dimension.

Me

Self‐awareness is essential for effective collaborations. There are two parts to this self‐awareness. The first part has to do with what we bring intellectually and personally to the collaboration and how we prepare ourselves for it. We will discuss that here. The second part has to do with monitoring ourselves during collaborations, as we just discussed. We address specific skills associated with that in the “Us” section below.

In the Intellectual dimension, we have knowledge, ideas, opinions, and intellectual biases related to a given topic of collaboration. In the Personal dimension, we have personal goals and agendas, beliefs and attitudes, and personal positions regarding the topic of collaboration. First and foremost, it is important to know where we stand in these areas. This is especially true with regard to our Personal attributes, which have significant emotional origins. Although it may be convenient to ignore them, doing so is likely to backfire in a collaboration. Ignored Personal attributes tend to come out sideways in collaborations, often at the most unfortunate times. So the first skill in the Me department is self‐awareness.

The second skill has to do with preparing for the collaboration. This has to do with our intent regarding the collaboration, as governed by our Directional dimension. Understanding our Intellectual and Personal attributes is a start, but then we must ask ourselves some fundamental questions.

- Will my Intellectual and Personal attributes, if brought to the collaboration, support what I understand to be our common goal?

- If not (i.e., I have Intellectual and Personal attributes that will work against our common goal), what am I willing to do about them going into the collaboration?

Regarding this question, there are a variety of things to consider in addition to adopting a genuine willingness to collaborate. For example, in the Intellectual dimension, if you know your ideas and opinions about the work or problem are significantly different from the other person's, you could decide to adopt the other person's ideas, try to find a middle ground, or come up with a brand‐new idea that may work for both of you. In the Personal dimension, depending on where your “issues” are, you could change your goals, agendas, beliefs, attitudes, or personal positions regarding the work. Although such changes should be considered, they are not always appropriate, and often we are not willing to make them.

Fortunately, however, there is another option. If, going into a collaboration, we are unwilling to change attributes that may tend to work against finding common ground and achieving the common goal, then we can at least choose to hold them lightly. That means that while we have chosen not to change the attributes going in, we have decided to keep an open mind regarding those attributes during the collaboration. I may go into a collaboration thinking my idea is better than the other person's, but I can at least be willing to hear them out and consider their ideas. And should I see merit in their ideas as I achieve a better understanding of them, I reserve the option of adopting all or part of the ideas. If, for example, I go into a collaboration with a personal agenda that a certain line cannot be crossed or it will threaten my budget, I can at least work with the other person to see if we can find a way to cross that line while adequately protecting my budget.

The point is that we are each responsible for doing all we can ahead of the collaboration to enable a successful outcome. That doesn't mean we should just roll over. It means we should do what we are willing to do and, at the minimum, hold our potentially conflicting attributes lightly. If we allow collaboration to happen, the creative process just might help forge a path to a mutually agreeable outcome. So, the underlying skill in the Me category is to have the ability, willingness, and courage to allow for a successful collaboration.

You

The other side of the coin in our collaborations is knowing the people we are interacting with (e.g., clients, stakeholders, teammates, coworkers, etc.), so we can optimize our interaction strategy with them. In the business world, knowing a person is focused on two primary categories: their business needs and their personal characteristics. Business needs spring from the person's position and role in the business, the person's associated business goals and concerns, and the circumstances surrounding the person in the context of the matter to be discussed. These things are associated primarily with the Intellectual dimension. People appreciate it when you know something about their business, circumstances, and history. If you are meeting someone for the first time, you can find a lot of information online (e.g., company website, LinkedIn, Facebook, etc.). You can also talk with people who know the person. However you do it, try to put yourself in the other person's shoes.

Personal characteristics include the elements of what we call PLOT: their Personality, Language (both verbal and body language), Opinion and frame of reference about the work and you, and Task approach (how they like to work and communicate). These things are primarily associated with the Personal dimension, especially opinion and frame of reference.

You can use PLOT as a tool to read people and formulate an interaction strategy. For example, you are about to meet with an executive you met once before to discuss the agenda for his executive offsite meeting. He is Type A and quite serious (Personality). He talks fast and waves his arms a lot (Language). He prides himself on how much work he can get done and thinks of himself as superior to most people, including you (Opinion/Frame of Reference). He is a big‐picture guy who doesn't think details are something he should get into and he likes to delegate (Task approach).

Given his PLOT, what is the best interaction strategy? He is certainly not the kind of guy who wants to spend all day brainstorming about possible agenda topics and activities. You are going into a collaboration with someone who probably doesn't like to collaborate, yet you have to find a way. You decide to meet him where he is. The meeting will be short, fast paced, and formal. He is not interested in building a relationship with you; he wants to get the meeting done and move on. You will talk fast and get to your points quickly. Instead of walking in with a blank sheet of paper, you will take a stab at framing out an agenda with options for topics and activities. That will put him in the role of evaluating and making quick decisions, things he is quite comfortable doing that reinforce his self‐image. The day of the meeting comes and your strategy works like a charm. You are in and out in ten minutes, he appreciated your preparation, and you have your agenda.

This example underscores the importance of reading and knowing the person with whom you will be collaborating. What would have happened if you had walked into the meeting without a strategy to optimize the collaboration? Sometimes, in fact, we find ourselves in that circumstance. We may learn about a last‐minute meeting with someone we have never met where there is no opportunity for preparation. In those cases you can apply PLOT in the moment when you meet and ask questions to find out about the person's business. That brings us to Us.

Us

As important as the Me and You skill sets are, the Us skills are probably the most important in collaboration. This is where the navigation really begins. At the heart of this skill set is the ability to sense, process, and respond in the moment during interactions to build shared space and alignment toward a common goal. As mentioned earlier, what is being aligned are the Intellectual and Personal dimensions of energy between you and the other person. We will address sensing, processing, and responding one at a time and then come back to how they all work together in collaborations.

Sensing has to do with monitoring the other person, ourselves, and the deeper messages of the interaction. It is the stuff of the Observer. What we are ultimately monitoring are the Intellectual and Personal dimensions of energy in ourselves and the other person. That means there is an intellectual component of the conversation and a personal component with an emotional genesis. To monitor these energies in others, we must monitor their indicators. These indicators include:

- Words. While it is certainly true that much of our communication happens in nonverbal ways, words remain a central form of communication. In particular, words—possibly augmented by visuals—are how you will learn about the other person's intellectual contributions to the collaboration. When people are being forthright, they may also express personal beliefs, attitudes, and positions through their words.

- Body language. Body language can tell us a lot about the other person's Personal dimension and reveal intellectual preferences as well. For example, if we inadvertently challenge someone's personal position about the work, we may see them push back or cross their arms. Most people read body language naturally, so we won't spend time here describing how to do it. Suffice it to say that we need to make sure we are paying attention to body language if we can actually see the other person.

- Tone. Even when we can't see the other person (e.g., during a teleconference), we can learn a lot about the Personal dimension and its associated emotions through a person's tone of voice and volume.

- Generosity. People can be generous in conversations or they can withhold information and contribute little. How generous people are to the collaboration with their engagement, willingness to listen, thoughtful ideas, and appropriate feedback can speak volumes about their intent.

Monitoring our own Intellectual and Personal energies is part two of the self‐awareness equation. Intellectually, we generally go into collaborations with specific ideas and opinions about the work. As the collaboration unfolds and we are exposed to new information and ideas, our own ideas and opinions may well change. We must monitor the collaboration for things that may change us intellectually.

Monitoring our Personal energies is more difficult but essential for most good collaborations, as discussed. Remember unintentional conflict and the many things that trigger it? Well, this is the place where those triggers push our emotional buttons. At the sensing stage, we have not yet reacted and we still have a choice about how to react (i.e., do we engage in conflict or go a different way?). The important part of sensing is to be aware of when a trigger pushes one of our emotional buttons; typically this occurs when we perceive that our work survival, comfort, reputation, or level of importance are being threatened.

Not all Personal energies in ourselves and others are negative, however, and it is equally important to monitor the positive developments. For example, if the other person has a personal position about the work that was contrary to yours and decides to let that go, you will certainly want to be aware of that. If a person's level of generosity in the collaboration suddenly increases, it reflects a positive shift in the person's Personal dimension.

Processing is what we do after sensing. It is done by our Guide. Whereas sensing provides us with information, processing helps us understand what it means. Once again, there are two sides to the equation.

- What information means to the other person. Understanding what information means to the other person entails translating the information into how it is affecting their Intellectual and Personal dimensions and how it is affecting the creation or erosion of shared space. For example, if I throw out an idea and the other person reacts in a snippy way, I know that intellectually she didn't like the idea and personally probably felt threatened by it. Depending on the magnitude and implications of the idea and the personal attributes of the other person, it may have also eroded trust and shared space. Conversely, if the other person likes my idea and agrees to it, I have successfully moved him intellectually. Personally, he may feel a higher degree of trust. He may feel positive emotions like relief, satisfaction, or even joy. Shared space grows.

- What the information means to you. Once you have the information from the last exchange, and you have arrived at what it does or may mean about the other person, you evaluate what all the information means to you in anticipation of a response. These are often your defining moments in a collaboration. For example, let's say I am easily offended by people who reject my ideas. I am offended because I am unwilling to consider other suggestions (Intellectual rigidity) and I make the rejection of my idea into a rejection of me and a condemnation of my abilities (Personal beliefs). I decide to argue in favor of my idea and to do it with some anger and righteousness; this is a clear path toward conflict.

In contrast, I may have prepared for the collaboration by holding my ideas and personal positions lightly, as we discussed earlier. I am not offended by the rejection as I can see that the snippy component of the other person's remark was born out of fear, and I am seeing the person's human condition. I am not condoning snippy behavior; I am simply understanding what it means—something about the other person, not me. I see this as an opportunity to ask the other person for ideas, to hear what he has to say and to model the kind of collaborative behavior I would like to see from him.

These examples show us that what we make things mean to us, based on our Intellectual and Personal attributes and energies, has a huge influence on our decisions and actions in a collaboration. What we make things mean to us can send us into battle, or it can turn a negative into a positive. It also shows us a defining moment when a trigger for conflict can be engaged or left alone. Given the magnitude of conflict in our businesses today and the huge prices we pay for it, we would be well advised to develop ourselves and our people with the skills and behaviors to see things for what they are and to choose not to take things personally. Doing so would help us avoid some of the conflict triggered by Environmental factors and interactions with people who are not as adept at managing their energies.

Responding is the second part of the Guide's job. It is essentially executing the plan and decision developed in the Processing step. However, there are many options for how you can respond. We look now at four things to consider in your responses.

- Effective questioning. Most collaborations include portions where people are trying to get to the bottom of things (e.g., reach a mutual understanding of the causes of a problem). During those interactions, you will likely have to ask probing questions in a way that doesn't threaten people. For example, if I were to ask the captain of the Titanic (had he survived), “What the heck were you thinking as you steamed at top speed across the Atlantic in the Titanic when you knew there were icebergs in the area?,” he would have undoubtedly responded in a defensive manner. However, if I asked him, “What were the factors that night that compelled you to conclude that the risk of an iceberg collision was minimal?,” he would respond quite differently and would appreciate my approach. Another aspect of effective questioning is not to script your questions too tightly in advance. Instead, let the last response, and your processing of that response, guide you in framing your next question. You will achieve an understanding more quickly this way, and the other person will know you are listening.

- Questions versus statements. There are times in collaborations when you need to make a point. But many a collaboration has gone awry because when people want to make a point, they often are more inclined to make a statement than ask a question. Avoid making statements based on your opinions only. Doing so can be risky. Instead, practice the art of making points with carefully worded questions. For example, if you are concerned that the manager you are talking with will not provide enough resources from her department to make a project successful, you may say something like “I'm concerned that the project could fail because you may not assign enough people from your department to support it.” That looks and feels like a direct confrontation, and it is guaranteed to close off any shared space you may have created. Alternatively, you might ask, “What is your strategy for identifying who in your department will support the project? How will you know when you have assigned enough people?” These questions are far more powerful and effective than making statements.

- Adjusting your role. In our interactions we all have roles that we play, and those roles often change as the conversation progresses and evolves. For example, in the first part of a collaboration, you may be in the role of a Strategist as you brainstorm with the other person about how to approach accomplishing a goal. Once an approach has been identified, however, the other person may want help thinking through a sticky point in the implementation of the strategy where you have had significant experience. To bring the greatest value to the collaboration, you would switch into the role of a Coach. While a thorough discussion of the collaborative roles is beyond the scope of this book, suffice it to say that you will bring the greatest value to your collaborations when you can recognize in the moment the optimal role to play and then step into it. Collaborations are severely limited and more prone to conflict when people are unwilling or unable to step out of the comfort zone of their preferred roles. While changing roles may sound mechanical, it helps to create a dynamic, empathetic, and responsive dance in the interaction. This has a tremendous effect on building shared space.

- Influencing others. We are all in business to get important work done, and it is essential that we are able to appropriately influence the positions, beliefs, and attitudes of others. How we influence others is the key. It is best to recognize that your influence during a collaboration is constant. Even your questions have influence. As you promote adjustments in the other person's Intellectual and Personal dimensions, you can see the results of your influence. Things to watch out for include coming on too strong, which can feel like bullying, and stating opinions without ensuring they are relevant and compelling to the other person. Communicating to the other person the relevancy of our ideas to their situation is far more powerful than simply blurting out an opinion. Because this type of communication is a very thoughtful way of aligning people with our ideas, people tend to appreciate the influence as opposed to feeling pushed. And, yes, this too builds shared space.

When we put Me, You, and Us together, tremendous resolution, creativity, and innovation can happen. The acts of knowing ourselves and others, responsibly preparing for collaborations, and sensing, processing, and responding with a common goal in mind make us powerful collaborators. Looking at how all of this comes together, two overarching points about collaboration emerge. First, collaboration is best accomplished with a strong degree of independence from the Intellectual and Personal dimensions. You are observing and processing information and cues about yourself and the other person and making navigational decisions based on information. You need to be objective, especially about yourself. To do that you will want to observe and make decisions from a vantage point where you aren't taking things personally and you aren't easily insulted. This takes practice, but it can be done. Second, in your collaborations, you are ultimately reading and responding to energy. You sense these energies through the various cues we discussed. We call these cues the other conversation. The other conversation represents the bigger picture of energy. Let's look at an example.

The Other Conversation

One type of collaboration that is increasingly common in business is when a project leader interviews executive stakeholders early in the project to find out about their ideas, preferences, and issues so they can be considered in project planning and direction. We will use this type of collaboration to illustrate the other conversation. Our stakeholder's name is Jane.

The narrative part of the story below characterizes the flow of the verbal conversation. The italicized comments characterize what I call the “other conversation,” where the real collaboration is happening. These comments are about what Jane and Joe are thinking and feeling, not what they are saying. Here is the story.

Joe arrives at Jane's office for the scheduled interview, having done his homework on Jane's business needs and personal characteristics.

| Jane: | I hope this interview is over quickly. I have so much to do. Does this guy have a clue about my business? |

| Joe: | I've done my homework on Jane and her business, and I'm going to show her that with my opening comments and questions.

Joe opens the conversation by stating his goal of understanding Jane's preferences regarding the project so they can be considered during project planning. He then summarizes his understanding of her position and how this project might affect her operation. |

| Jane: | He really understands my business! He obviously took some time to get to know me. I appreciate that. Now what is his agenda?

Jane states her appreciation for Joe's “homework” and then begins to talk about her business and concerns around the project. |

| Joe: | I sense she is opening up but may still have doubts about my intent. I'll show her my intent through my questions, comments, and thoughtful listening.

Joe listens carefully and asks questions to clarify his understanding of what Jane is saying. Jane mentions that Joe asks good questions and begins to ask some of her own questions about the project. |

| Jane: | He seems to not just have his own interests in mind, and genuinely wants a good outcome for me and my business on this project. That's great! I'm going to do what I can to help him too.

As this dialogue continues, the conversation becomes more open and frank. Agreements are reached on certain aspects of the project and how Jane would be given review opportunities at specific project milestones. |

| Joe: | I think she really trusts and appreciates what I am trying to do. She is giving me some great information that will really help me and the project! |

| Jane: | Wow! His questions made me think about things I wasn't even aware of about my business. I'll have to take a closer look at those. Meanwhile, this has been a valuable conversation—time well spent. And I like this guy, Joe. I wasn't sure about him before, but I trust him now. |

By the end of the conversation, Joe has all the information he needs and thanks Jane for a pleasant and productive meeting.

This example is pretty simplistic but helps illustrate the point. The other conversation in our collaborations is real, it always happens, and it is by far more important than the surface‐level conversation. The surface‐level conversation is about words. The other conversation is about the dynamics of energy and the truth of the matter. You can see from the other conversation how shared space between Joe and Jane continued to open up as the conversation progressed. This led to a very successful outcome. This story and its outcome illustrate the fact that we must help people operate effectively below the surface as well as above the surface to improve their collaboration capabilities.

Not all of our collaborations are one on one. Collaborations often include multiple participants. We turn our attention now to group collaborations.

Group Collaboration

In this section we define group collaboration and then address it in two common forms. First, we dive into the collaborative group conversation, a one‐time event that usually comes in the form of a meeting. Second, we look at longer‐term collaborative efforts, which usually come in the form of projects.

Defining Group Collaboration

Group collaboration is when three or more people work together in concert toward common goals. All of the ingredients of one‐on‐one business interactions absolutely apply to group collaboration. The concept of creating shared space together also applies. However, the addition of people increases the complexity of the interactions and requires that we recognize group dynamics in the collaboration that contribute to and erode the creation of shared space and positive outcomes.

The Collaborative Group Conversation

Collaborative group conversations are extremely common in business and will continue to gain in both importance and frequency as the Fourth Industrial Revolution unfolds. Some of these conversations produce successful outcomes; others produce just the opposite. Overall, we need to up our game. As in one‐on‐one collaborations, the Environmental dimension can have a tremendous influence on group conversations. For example, on the negative side, anything in the enterprise that creates factions and inappropriately elevates the importance of personal agendas will detract from the collaborative group conversation. Similarly, things in the enterprise that bring up fear, scarcity, or survival issues will make the creation of shared space and positive outcomes much more difficult. On the positive side, collaborative cultures and a healthy enterprise go a long way toward promoting successful group collaborations. The bottom line here is that too many collaborative group conversations are doomed before they get started because of unhealthy enterprises that breed unintentional conflict.

As for the conversations themselves, collaborative group conversations have both similarities to and differences from one‐on‐one conversations. Like one‐on‐one conversations, the Collaboration Dynamic and the four dimensions of energy apply, and creating shared space is equally important. The differences have to do with dynamics within groups that don't exist in one‐on‐one interactions. Let's review some of the similarities and differences to inject the perspective of energy onto group discussions and provide strategies for promoting effective group collaborations.

Individual and Group Alignment

We know that alignment is important in collaborative group conversations, but exactly what is being aligned and how does alignment work? The answer is that both individuals and the group as a whole are being aligned. Individual alignment is finding common ground and direction between every individual and every other individual. This occurs, for example, when two people in the group express differing opinions and then work toward alignment through their interactions. Taken literally and to the extreme, aligning everyone with everyone would require far too many individual conversations. Fortunately, that is not the end goal, nor is that the way colloboration works in group conversations.