27. MOVE CLOSER

![]()

IT’S BEEN SAID many times over that in order to create more interesting images, move closer to the subject or action. The same applies to portrait photography. We’re pretty comfortable staying at a respectable distance (physically or optically) from our subject; however, zooming in or physically moving closer to your subject also moves the viewer closer to them, capitalizing on the relationship you create between subject and audience, be it a portrait of a daughter for her mother or a Wall Street executive for the readers of an economic periodical.

Getting closer to your subject creates greater intimacy with them (Figure 27.1). Humans, as social creatures, heavily read into non-verbal communication, such as body language, gesture, and facial characteristics. Reducing the perceived distance between subject and camera pushes the viewer into a distance in which non-verbal cues are easily read. As a result, the viewer becomes more interested in the image and the subject since they are given a greater opportunity to learn more about him without the use of words or audio.

Not all portraits need to be made at very close distances for them to be engaging. I don’t mean to argue away from full and medium shots (especially since I tend to gravitate toward them as an environmental portrait shooter). I will argue, though, that we can do a better job of moving the viewer closer to the subject occasionally to exploit their tendency to really focus on the subject. Some of the most powerful portraits throughout history (think about Steve McCurry’s portrait of Sharbat Gula, better known to Western audiences as The Afghan Girl, who appeared on a 1985 National Geographic magazine cover) are those that move the viewer so close to the subject that everything else around the subject becomes void.

The question, then, becomes: how close is too close? The answer depends on the purpose of the portrait. I think it’s best to answer this question with a few things that you might want to avoid regarding the top and bottom of a person’s head.

First, avoid cutting through the subject’s chin with the bottom of the frame (Figure 27.2). It’s best to always give the indication that the subject does indeed have a neck, so composing the bottom of the frame (especially for headshots) so the neck is visible is a good idea (Figure 27.3).

27.1 Getting closer allows you to frame your portraits tighter and convey a great deal of intimacy with the subject, like I did with a portrait of writer and artist Kippra Hopper.

ISO 400; 1/40 sec.; f/4; 75mm

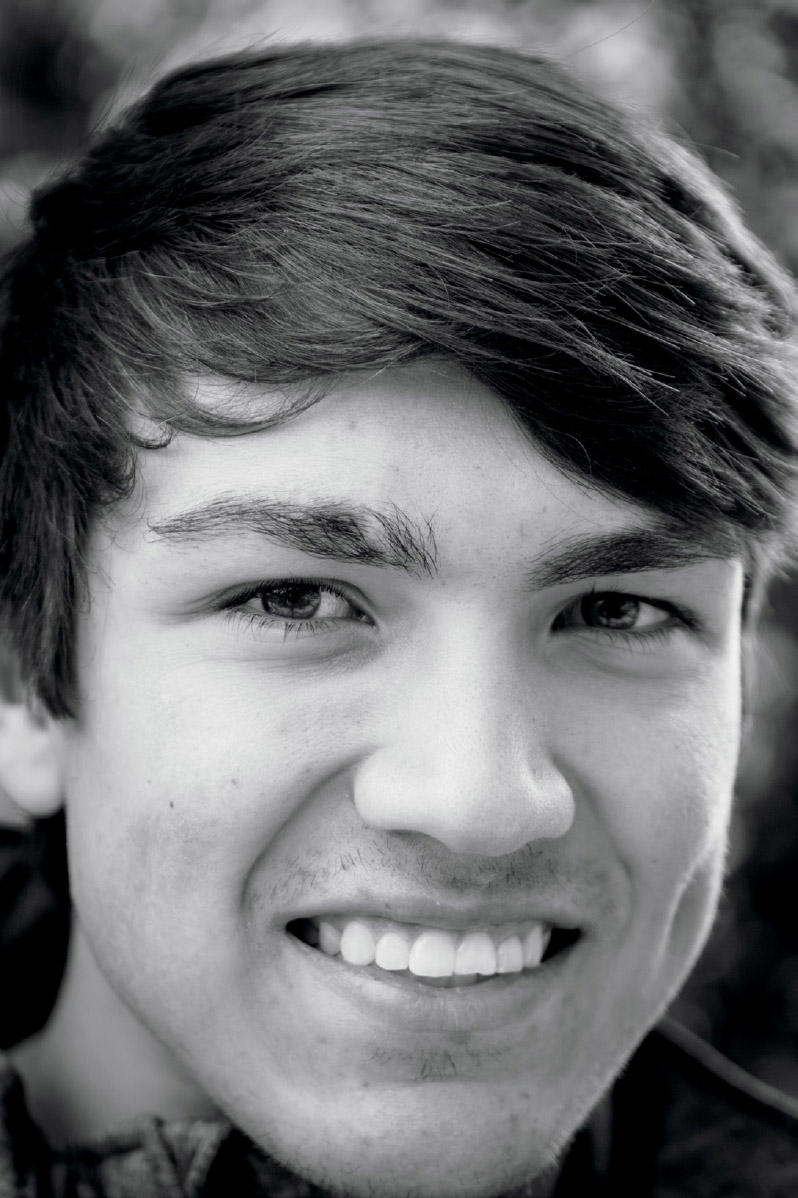

27.2 Although this image feels too tight to begin with, one of the more irksome characteristics is the chin being cut off.

27.3 A more backed out framing of the portrait allows the chin “room to breathe” and the next is exposed, creating a more complete, natural visualization of the person being photographed.

ISO 100; 1/640 sec.; f/2.8; 70mm

Second, if you’re tight enough to be cutting off the chin, consider how much of the top of the head is being cut. It has become trendy over the years to create portraits and headshots so close to the subject that the top of the head is cut off. I like this proximity, and it certainly forces the eye to engage the subject. However, there’s a fine line between cutting too far into the forehead and cutting too little into the top of the head. If your subject has a full head of hair, I suggest cutting no lower than the hairline, and instead, leaning toward leaving a good bit of that hair showing underneath the edge of the frame (Figure 27.4). However, don’t cut just a few millimeters of hair out of the frame for risk of making the image look incomplete (Figure 27.5). This is a rather subjective call. Finding a middle ground between intimacy and awkward composition is the ideal solution here.

Finally, a warning: when moving in close to your subject with a wide focal length (shorter than 50mm), beware of how distorted your subject becomes. Wider focal lengths increase the level of optical distortion present in the image (Figure 27.6). Place a human subject amidst that distortion, and our perception of reality becomes, well, distorted. The closer you move a wide focal length to your subject, the more likely his nose will elongate, his chin will become larger, and his face will bulge toward the camera. The closer you compose his face to the side of the frame, the more it will stretch toward that side. The effect increases as the focal lengths get wider. All lenses distort to some degree, but wider focal lengths do so more obviously. It’s a good idea to avoid moving a wide focal length so close to your subject that all you can see in the frame is his head. It won’t come across as the subject would like.

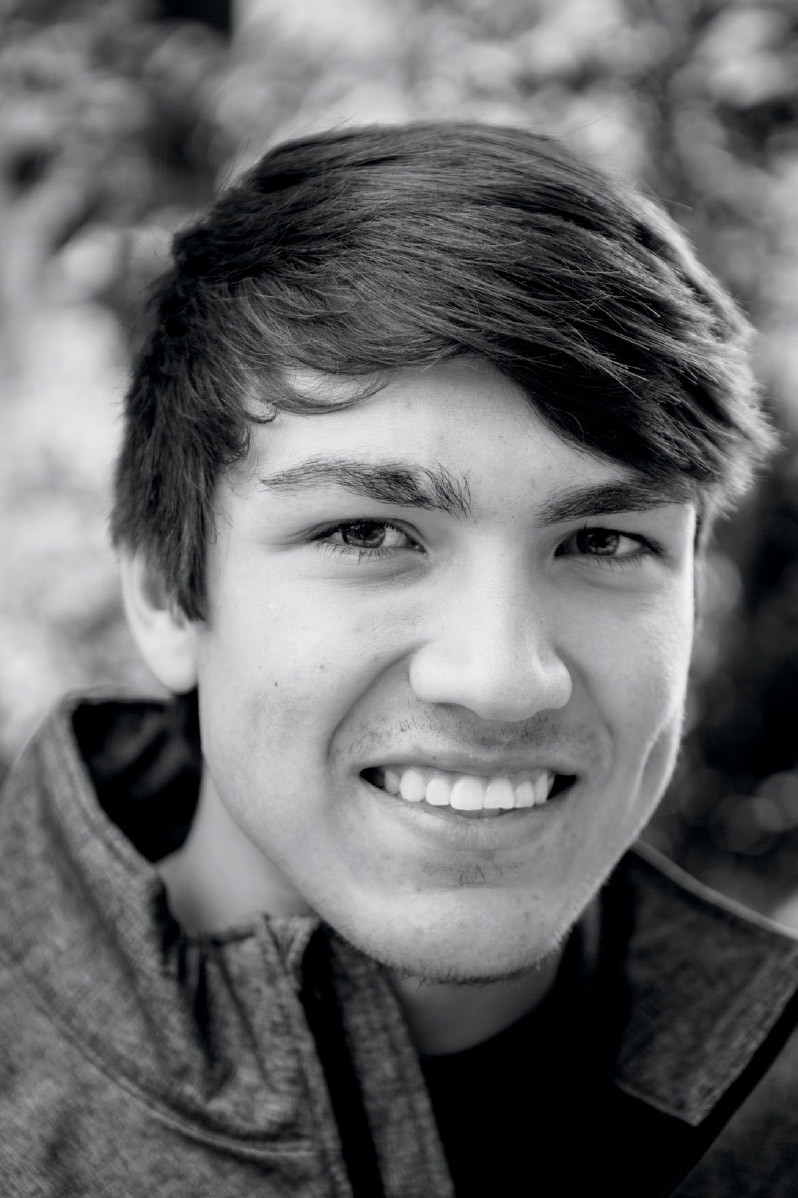

27.4 Cutting into the top of the head to create a framed intimacy with the subject is stylistically popular, as long as there’s still enough hair underneath the top edge of the frame to give the viewer context to the subject’s head and form.

ISO 200; 1/320 sec.; f/1.8; 85mm

27.5 Consequently, cutting off too little of the top of the head simply results in a poorly composed image that leaves the viewer wondering about the top of the subject’s head. This is visual tension best reduced as much as possible.

27.6 In trying to create a portrait of a weary bikepacker after a couple days in the desert, I pushed a wider focal length close to his face, making it bulge toward the camera. Personally, I don’t care for how much it does push toward the camera while also composing the bottom of his beard out of the frame.

ISO 200; 1/400 sec.; f/2.8; 130mm