8. CONTROL THE APERTURE

![]()

IF THERE’S ONE mechanism I favor over the others on the camera, it’s the aperture. Actually, the aperture is located in the lens, not the camera body, and is comprised of a ring of overlapping metal leaves that open or close based on the user’s preference. Like ISO and the shutter, the aperture has a technical function: it’s the mechanism that completes the exposure triangle. It’s also a mechanism that can provide great aesthetic value for portraits.

The aperture controls an image’s depth of field—the amount of an image that appears in focus while looking into the frame. Depth of field is determined by the point at which the image is focused, or the plane of critical focus. Depth of field expands toward and away from the camera based on the aperture setting. This makes the aperture one of the most effective tools at the photographer’s disposal because changing its size effects the perceived depth of field in an image. Aperture values, which are often referred to as f-stops, are denoted as fractions related to the size of the opening in the lens (Figure 8.1). The more open the aperture, the smaller the identifying denominators will be; e.g., f/2.8, f/4, and f/5.6. The more closed the aperture, the larger the identifying denominators will be; e.g., f/11, f/16, and f/22. Essentially, the smaller the denominator, the more open the aperture, and vice versa.

Now, all of these numbers do translate into visual results. The more open an aperture is, the shallower the depth of field, i.e., the more out of focus the background behind your subject and the foreground in front of them will be. Conversely, the more closed the aperture is, the wider the depth of field will be. For example, a portrait made with an aperture set to f/1.8 (Figure 8.2) will have considerably less depth of field and a more out-of-focus background than the same portrait made with an aperture set to f/8 (Figure 8.3).

The depth of field in an image says quite a bit about the important visual and narrative elements of the photo. Visually, a completely out of focus background can be attractive, but the image may lack visual depth. Of course, this all depends on how you compose a portrait. Narratively, an out of focus background drives the viewer’s eye directly to the most important subject or area in the frame. The significance of other indiscernible subject matter is reduced (Figure 8.4). To make a cinematic analogy, what is left in focus—your portrait subject—is the lead actor of the image, while everything else is the supporting cast. Likewise, a background that is in focus can be busy and distracting, but if composed purposefully, it might also let the environment in which the subject is photographed play a stronger supporting role (Figure 8.5). As you’ll see later in this book, much of how depth of field (or the lack thereof) affects the image is also reliant upon how the portrait is composed.

Typically, though, photographers control the aperture in order to direct the majority of attention to the main subject or subjects of the portrait. This means we tend to think about portraits as having a relatively shallow depth of field in order to command the viewer’s eye to our subject. I recommend starting out with an aperture setting of f/4 or f/5.6 to obtain a shallow depth of field, and working your way to a smaller aperture if you desire more area in the frame to be in focus.

8.1 The maximum aperture of any lens is typically labeled on the front of the barrel. In this case, the maximum aperture is 1:3.5-5.6. This means that at the widest focal length of this zoom lens, the maximum aperture is f/3.5. At the longest focal length, it is f/5.6. This is referred to as a variable aperture lens.

8.2 At f/1.8, a very open aperture for any focal length, the depth of field is minimal. This concept is conveyed here by the large amount of out-of-focus area in the image.

ISO 100; 1/1600 sec.; f/1.8; 85mm

8.3 When the aperture is stopped down to f/8, the depth of field increases. This means more of the portrait in front of and beyond the subject will be in focus. In this image, this change in depth of field makes the background busy and distracting.

ISO 100; 1/80 sec.; f/8; 85mm

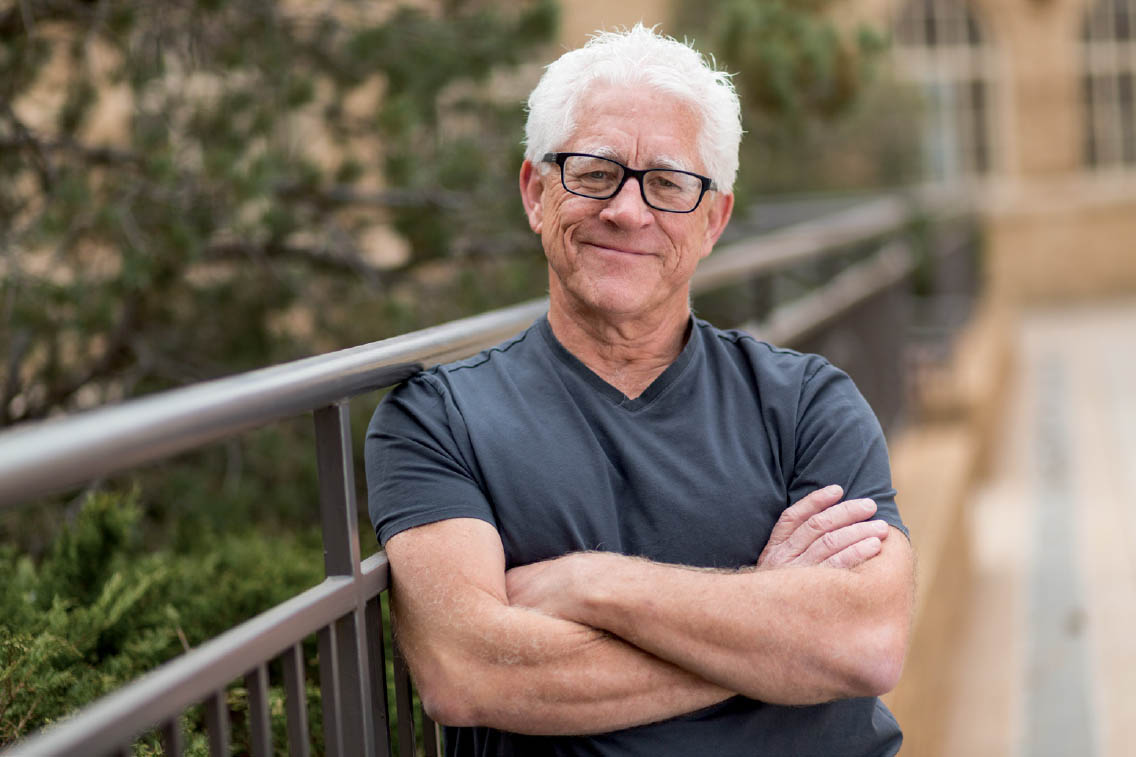

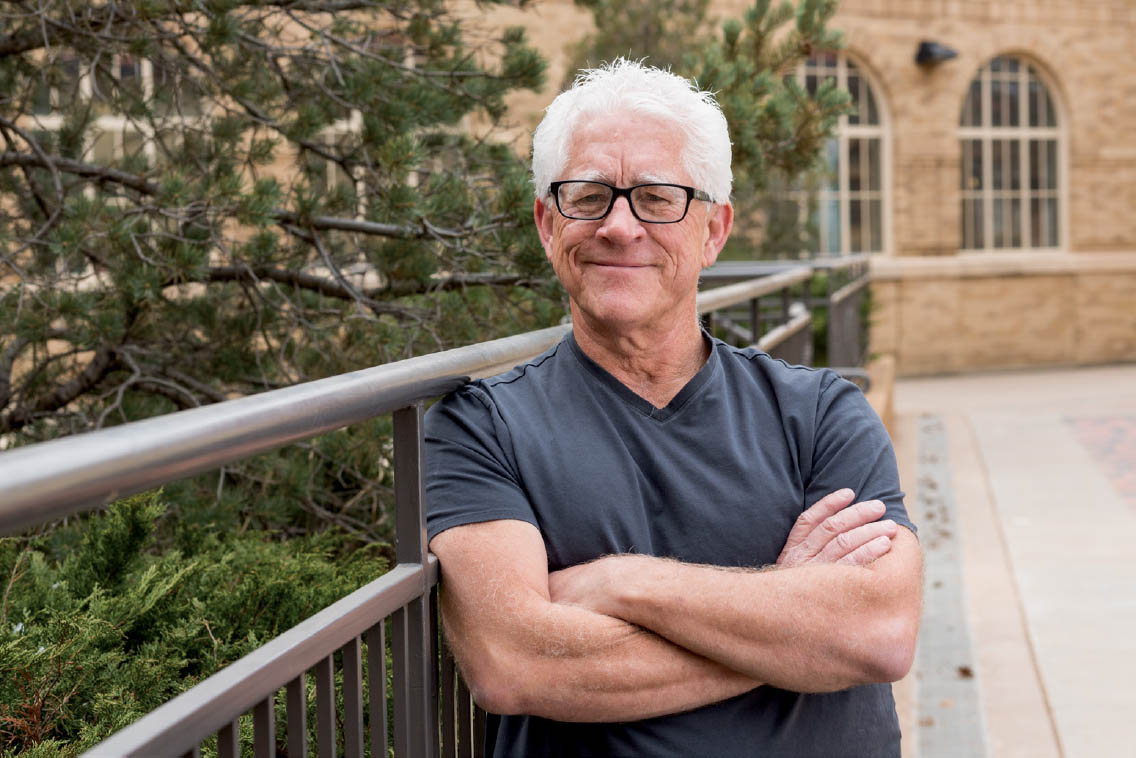

8.4 I set the aperture to f/2.8 for this portrait so the trees in the background wouldn’t take away from the portrait subject.

ISO 200; 1/800 sec.; f/2.8; 150mm

8.5 I used an aperture of f/16 for this environmental portrait of Logan to ensure the ancient, man-made hole appeared in focus in the foreground. In this case, the environment shows the portrait subject’s passion for history and archaeology.

ISO 400; 1/50 sec.; f/16; 17mm

8.6 Using a 50mm lens set to f/4 dropped the background out of focus enough to not be a distraction.

ISO 100; 1/60 sec.; f/4; 50mm

8.7 Although still not necessarily a distraction, using the same lens and aperture combination at a distance farther from the subjects brings the background more into focus, essentially increasing the image’s depth of field.

ISO 100; 1/60 sec.; f/4; 50mm

Distance and Visual Depth of Field

The aperture is not the only thing that affects the depth of field. Regardless of lens and aperture, the visual effect of the aperture setting will change based on your distance from your subject. The closer you move to your subject and maintain focus on it, the more out of focus the background will appear (Figure 8.6). The more distance between your camera and the subject, the larger the depth of field will seem (Figure 8.7). Technically, the depth of field is not changing; it only appears so because you are bringing the plane of critical focus either closer to the camera or farther away from it. Depth of field expands from the plane of critical focus and is limited by the optical possibilities of your lens, so these effects may come in handy either creatively or strategically during your shoot.