47. ARCHITECTURE

ONE OF THE most remarkable aspects of international travel is the opportunity to learn about a culture and its history through architecture. Cityscapes are time capsules, telling the stories of the years through line, shape, material, and juxtaposition. From the complexity of a column, to the smoothness of a well-worn stair, every inch of a structure speaks of the past as well as the present.

Whereas the architect works artistically on a grand visual scale, the photographer must choose whether to tell the story of a building through its full form or through the abstract details within. Excellent architectural photography can inspire emotion and the urge to travel just as easily as a stunning landscape, because architecture is one of the most apparent examples of human ingenuity and creativity. What began as a pursuit to put a roof over our heads transformed into complicated feats of engineering, articulate design, and a sense of overwhelming grandeur.

Context

When I photograph architecture, one of my primary considerations is the context of the structure—the historical context of the design, the physical context of the natural surroundings or other structures, the social context of whether the structure was appreciated or reviled. Context is what makes a structure more than just a pile of bricks or a skeleton of steel. Context is why the structure matters and how it became a part of a location’s unique story.

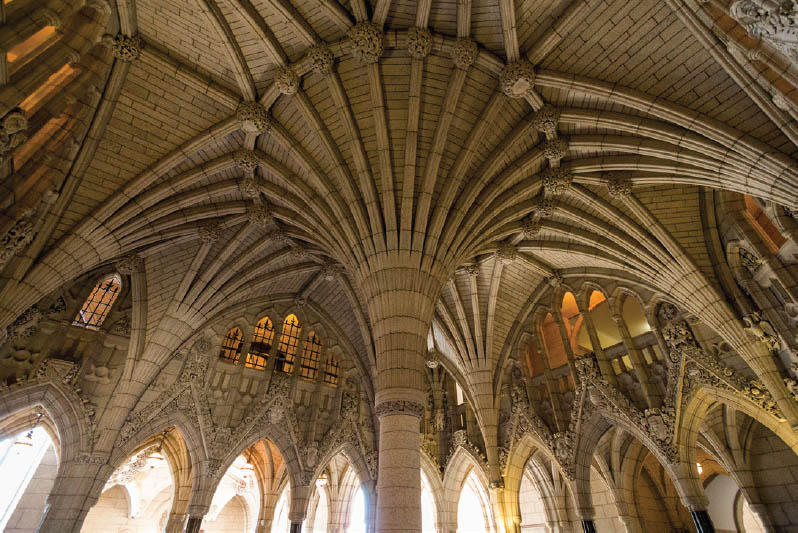

Each architectural movement had a specific set of values. Brutalist architects stressed function and rawness over classic concepts of beauty. They worked with rough textures of concrete and emphasized repetition. When I photograph a brutalist structure like the Met Breuer or the Salk Institute, I deliberately highlight the context of the brutalist movement. I pay close attention to a structure’s most representative features: the texture (Figure 47.1), the repetition (Figure 47.2), and the right angles (Figure 47.3). When I photograph a gothic structure, I pay attention to the ornate details (Figure 47.4), the arches (Figure 47.5), and the sense of soaring height (Figure 47.6).

47.1 The Met Breuer, New York, New York

ISO 800; 1/160 sec.; f/3.5; 18mm

47.2 The Salk Institute, La Jolla, California

ISO 200; 1/1000 sec.; f/1.8; 50mm

Physical context is equally important in an architectural photograph. The enormous peaked structure of Alberta’s Prince of Wales Hotel echoes the mountains that surround it. By shooting from a distance, you ensure that the viewer gets the full benefit of the mountainous context (Figure 47.7). When a structure seems to grow up almost impossibly in the narrow crevice between two other buildings, a successful photo might mirror that context with a tight, claustrophobic crop (Figure 47.8). Conversely, negative space is a powerful form of physical context. A structure that seems to pop up out of nowhere should be photographed in a way that makes use of that openness (Figure 47.9).

47.3 The Salk Institute, La Jolla, California

ISO 100; 1/800 sec.; f/3.5; 10mm

47.4 Girona, Spain

ISO 100; 1/250 sec.; f/4; 17mm

47.5 Parliament of Canada, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada

ISO 25000; 140 sec.; f/3.5; 10mm

47.6 Almudena Cathedral, Madrid, Spain

ISO 1250; 1/40 sec.; f/4.5; 26mm

47.7 Prince of Wales Hotel, Alberta, Canada

ISO 125; 1/400 sec.; f/6.3; 79mm

47.8 Chicago, Illinois

ISO 100; 1/250 sec.; f/5.6; 50mm

47.9 Wood End Light, Provincetown, Massachusetts

ISO 400; 1/50 sec.; f/29; 22mm

47.10 Monroe and Michigan, Chicago, Illinois

ISO 100; 1/160 sec.; f/8; 300mm

47.11 Yuma Territorial Prison, Yuma, Arizona

ISO 160; 1/2000 sec.; f/4; 10mm

Conditions

Because architecture is so nuanced, certain conditions will work better for some buildings than others. A heavily detailed facade will be more apparent with strong side light that creates shadows and defines dimension (Figure 47.10). Stark white walls will look more compelling in direct sunlight and with the use of a polarizing filter (Figure 47.11). Narrow European streets will have more interesting atmosphere when the sun is low in the sky and casts long shadows (Figure 47.12). If you fall in love with a structure, try to revisit it across multiple times of day or in different weather conditions to find the scenario that brings out its personality or provides interesting atmosphere.

47.12 Cáceres, Spain

ISO 100; 1/200 sec.; f/5.6; 85mm

Perspective

When it comes to photographing architecture, my favorite advice is simple: look up. A day spent exploring architecture should end with a smile and a sore neck. So many times, I’ll share a photo that I got while shooting with friends and they’ll say, “I didn’t see that. Where was it?” Nine times out of ten, my answer is “up.” You never know what sort of amazing geometric patterns (Figure 47.13), interesting lighting, or bizarre shapes you’ll be able to find when you turn your lens upward. Architecture is so impressive because of its scale, so rather than focusing only on the parts of the structure at your eye level, look up.

Once you’re in the habit of looking up, you may start to pick up on a common frustration: the appearance of converging lines and leaning buildings. The closer you are to a building or the wider your lens, the more extreme the visual distortion will be. In some photographs, distortion and convergence work well (Figure 47.14), but if you’re going crazy trying to keep lines parallel and angles perpendicular, then you have a few options: move farther away and zoom in, use a tilt-shift lens, or make perspective adjustments in post-processing. Not every perspective will work with every structure. Experiment with different shooting locations, interesting angles, and swapping out lenses to find what works best for the buildings you want to photograph.

Abstract

Sometimes the most interesting way to study architecture is to examine the smaller portions that make up the whole. Thanks to Instagram, architectural abstracts are more popular than ever. Photographers all over the world are isolating lines, colors, shadows, and repeating elements in interesting and engaging photographs.

Anything can make an interesting architectural abstract, from unique lighting conditions and shadows (Figure 47.15) to reflections (Figure 47.16) and ornate details. After I photograph the wider images of a structure, I like to focus in on the little nuances that make it unique. A series of abstract images of a building can speak volumes about its cultural and historical context as well.

47.13 Bank of Canada, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada

ISO 125; 1/2500 sec.; f/3.5; 10mm

47.14 Santa Maria del Fiore, Florence, Italy

35mm film

47.15 The Getty Center, Los Angeles, California

ISO 100; 1/500 sec.; f/4.5; 10mm

47.16 Chicago, Illinois

ISO 320; 1/40 sec.; f/10; 70mm