7

Making it Happen

You can tell whether a man is clever by his answers. You can tell whether a man is wise by his questions.

—Naguib Mahfouz1

When Julie Morath came on board as chief operating officer at Children's Hospital and Clinics in Minneapolis, Minnesota, her goal was simple: 100% patient safety for the hospitalized children under her care.2 The goal may have been simple. How to accomplish it was not. This was late 1999, and few people were talking about patient safety. It's not that most clinicians thought patients were completely safe from mistakes and harm; it's just that they tended to think that when things went wrong, someone was to blame. This made it hard to talk about the problem. Nurses and doctors, Morath knew, first had to become willing to speak up to report errors if was going to be possible to reduce the incidence of harm. In short, she needed the data on what was happening, when, and where. Only then could the hospital find new ways to enhance the safety of all of the vulnerable young patients at their six medical facilities in the Twin Cities.

The Leader's Tool Kit

In previous chapters, we saw how a lack of psychological safety stopped a NICU nurse from speaking up about a possible medication error for fear of annoying the physician. We saw how well-trained clinicians at a cutting-edge medical facility failed to question a fatal chemotherapy dosing regimen over a period of several days. These situations both took place in settings where a lot was going on.

Tertiary care hospitals, like Children's, are complex. It's challenging to get every single task done perfectly every single time. To begin with, every patient is different. No two care episodes are identical. Upping the ante, the highly-interdependent work of patient care must be seamlessly coordinated among narrow specialists with complementary knowledge and skills – who may not even know each other's names. Multiple, interdependent departments – pharmacy, laboratory, physicians, and nursing – who have conflicting priorities about what service to provide at what time must coordinate their actions for safe care to be consistently delivered. And so the organization had long accepted that things would occasionally go wrong. A certain number of slip-ups and crossed wires was just the way things were. It wasn't discussed much, and there was an unfortunate tendency to blame individuals (rather than system complexity) for errors that slipped through the cracks and led to patient harm.

Morath felt that this attitude had to change if progress was to be made. She needed a leadership tool kit to get this done. In retrospect, what happened to profoundly shift attitudes and behaviors at Children's can be divided into three categories: setting the stage, inviting participation, and responding productively.

Setting the Stage

As soon as she took the job, Morath began speaking to large and small groups in the hospital to explain that healthcare delivery, by its nature, was a complex system prone to breakdowns. She presented new research and statistics on medical adverse events to educate everyone about their prevalence. She introduced new terminology (“words to work by”) that altered the meaning of events and actions in important ways; for instance, instead of an “investigation” into an adverse event, the hospital would use the term “study;” instead of “error” she suggested people use “accident” or “failure.” In subtle but important ways, Morath was trying to help people think differently about the work – and especially about what it means when things go wrong. These leadership actions comprise what I refer to as framing the work.

Frames consist of assumptions or beliefs that we layer onto reality.3 All of us frame objects and situations automatically. Our focus is on the situation itself, and we are typically blind to the effects of our frames. Our prior experiences affect how we think and feel about what's presently around us in subtle ways. We believe we're seeing reality – seeing what is there. For instance, if we frame medical accidents as indications that someone screwed up, we will ignore or suppress them for fear of being blamed or of pointing the finger at a colleague. However, we can shift our automatic frames and create a shared frame that more accurately represents reality. More information about framing the work is provided later in this chapter. But when Morath began to give presentations that called attention to hospital care as a complex, error-prone system, what she was doing was framing the work – or, more accurately, reframing it. Her goal was to help people shift from a belief that incompetence (rather than system complexity) was to blame. This shift in perspective would prove essential to helping people feel safe speaking up about the problems, mistakes, and risks they saw.4

In setting the stage for open discussion of error, Morath also communicated urgency about the goal of 100% patient safety. I consider this an important stage-setting act because it helped people reconnect with the reasons they went into healthcare in the first place: to save lives. This reminder helped motivate people to do the hard work of reporting, analyzing, and finding ways to prevent harm. In short, with an emphasis on the complex and error-prone nature of the work, and a reminder of what was at stake (children's lives), Morath had set the stage for candor. But that was not enough to make it happen.

Inviting Participation

As you may imagine, hardworking neonatal nurses and experienced pediatric surgeons did not immediately flock to Morath's office to confess to having made or seen mistakes. People found it easier to believe that medical errors happened elsewhere rather than in their own esteemed institution. Even if they understood, deep down, that things can and do go wrong, it was not front of mind, and they genuinely believed they were providing great care.

Morath, hearing silence from the staff, stopped to consider. I'm sure it crossed her mind to try again – to re-explain the complex, error-prone nature of tertiary care hospital operations so as to correct the staff's implicit response that nothing was going wrong. If so, she resisted the temptation to lecture. Instead, she did something that was as simple as it was powerful. She asked a question. “Was everything as safe as you would like it to have been this week with your patients?”5

The question – genuine, curious, direct – was respectful and concrete: “this week,” “your patients.” Its very wording conveys genuine interest. Curiosity. It makes you think. Interestingly, she did not ask, “did you see lots of mistakes or harm?” Rather, she invited people to think in aspirational terms: “Was everything as safe as you would like it to be?” Sure enough, psychological safety started to take hold. People began to bring up incidents that they had seen and even contributed to.

Morath enhanced her invitation to participate with several structural interventions. First, she set up a core team called the Patient Safety Steering Committee (PSSC) to lead the change initiative. The PSSC was designed as a cross-functional, multilevel group to ensure that voices from all over the hospital would be heard. Each member was invited with a personal explanation for why his or her perspective was sought. Second, Morath and the PSSC introduced a new policy called “blameless reporting” – a system inviting confidential reports about risks and failures people observed. Third, as people began to feel safe enough to speak up, Morath led as many as 18 focus groups to make it easy for people throughout the organization to share concerns and experiences.

These simple structures made speaking up easier. When you join a focus group, your input is explicitly requested. It feels more awkward to remain silent than to offer your thoughts. In this way, the voice asymmetry described in Chapter 2, in which silence dominates because of the inherent risks of voice, is mitigated.

Responding Productively

Speaking up is only the first step. The true test is how leaders respond when people actually do speak up. Stage setting and inviting participation indeed build psychological safety. But if a boss responds with anger or disdain as soon as someone steps forward to speak up about a problem, the safety will quickly evaporate. A productive response must be appreciative, respectful, and offer a path forward.

Consider the “focused event analysis” (FEA), a cross-disciplinary meeting that Morath instituted at Children's to bring people together after a failure. The FEA represents a disciplined exploration of what happened from multiple perspectives – like the proverbial blind men around the elephant. In this setting, however, the goal is not to fight about who was right, as the blind men did, but rather to identify contributing factors with the goal of improving the system to prevent similar failures in the future.6 The FEA is thus a prime example of responding productively.

Equally important, the blameless reporting policy enabled productive responses to messengers who brought bad news about an error or mishap. Instead of expecting blame or punishment, the healthcare personnel at Children's began to expect – and experience – appreciation for their effort in bringing valuable information forward.

This goal of this chapter is to provide further examples of specific ways leaders build psychological safety in their organizations by setting the stage, inviting participation, and responding productively. With some practice and reflection, this tool kit is available to any leader wishing to create psychological safety. Table 7.1 summarizes the framework. To develop these behavioral tools, I drew from both research and my years of experience studying and consulting with organizations around the world.

Table 7.1 The Leader's Tool Kit for Building Psychological Safety.

| Category | Setting the Stage | Inviting Participation | Responding Productively |

| Leadership tasks |

Frame the Work

Emphasize Purpose

|

Demonstrate Situational Humility

Practice Inquiry

Set up Structures and Processes

|

Express Appreciation

Destigmatize Failure

Sanction Clear Violations |

| Accomplishes | Shared expectations and meaning | Confidence that voice is welcome | Orientation toward continuous learning |

How to Set the Stage for Psychological Safety

Whenever you are trying to get people on the same page, with common goals and a shared appreciation for what they're up against, you're setting the stage for psychological safety. The most important skill to master is that of framing the work. If near-perfection is what is needed to satisfy demanding car customers, leaders must know to frame the work by alerting workers to catch and correct tiny deviations before the car proceeds down the assembly line. If zero worker fatalities in a dangerous platinum mine is the goal, then leaders must frame physical safety as a worthy and challenging but attainable goal. If discovering new cures is the goal, leaders know to motivate researchers to generate smart hypotheses for experiments and to feel okay about being wrong far more often than right. In this section, I'll first explaining how and why framing the work includes reframing failure and clarifying the need for voice. From there I'll move on to another stage-setting tool in the leader's tool kit: motivating effort.

Framing the Work

Reframing Failure

Because fear of (reporting) failure is such a key indicator of an environment with low levels of psychological safety, how leaders present the role of failure is essential. Recall Astro Teller's observation at Google X that “the only way to get people to work on big, risky things…is if you make that the path of least resistance for them [and] make it safe to fail.”7 In other words, unless a leader expressly and actively makes it psychologically safe to do so, people will automatically seek to avoid failure. So how did Teller reframe failure to make it okay? By saying, believing, and convincing others that “I'm not pro failure, I'm pro learning.”8

Failure is a source of valuable data, but leaders must understand and communicate that learning only happens when there's enough psychological safety to dig into failure's lessons carefully. In his book The Game-Changer, published while he was still CEO of Proctor and Gamble, A.G. Lafley celebrates his 11 most expensive product failures, describing why each was valuable and what the company learned from each.9 Recall, also, Ed Catmull's assurance to Pixar animators, that movies always start out bad, to help them “uncouple fear and failure.”10 Here, Catmull is making a leadership framing statement. He is making sure that people know this is the kind of work for which stunning success occurs only if you're willing to confront the “bad” along the way to the “good.” Similarly, OpenTable CEO Christa Quarles tells employees, “early, often, ugly. It's O.K. It doesn't have to be perfect because then I can course-correct much, much faster.”11 This too is a framing statement. It says that success in the online restaurant-reservation business occurs through course correction – not through magically getting it right the first time. Quarles is framing early, ugly versions as vital information to make good decisions that lead to later, beautiful versions.

Learning to learn from failure has become so important that Smith College (along with other schools around the country) is creating courses and initiatives to help students better deal with failures, challenges, and setbacks. “What we're trying to teach is that failure is not a bug of learning, it's a feature,”12 said Rachel Simmons, a leadership development specialist in Smith's Wurtele Center for Work and Life and the unofficial “failure czar” on campus. “It's not something that should be locked out of the learning experience. For many of our students – those who have had to be almost perfect to get accepted into a school like Smith – failure can be an unfamiliar experience. So when it happens, it can be crippling.”13 With workshops on impostor syndrome, discussions on perfectionism and a campaign to remind students that 64% of their peers will get (gasp) a B-minus or lower, the program is part of a campus-wide effort to foster student resilience.

Note that failure plays a varying role in different kinds of work.14 At one end of the spectrum is high-volume repetitive work, such as in an assembly plant, a fast-food restaurant, or even a kidney dialysis center. Failing to correctly plug a patient into a dialysis machine or install an automobile airbag in precisely the right manner can have disastrous consequences. So in this kind of work it's vital that people eagerly catch and correct deviations from best practice. Here, celebrating failure is a matter of viewing such deviations as “good catch” events and appreciating those who noticed tiny mistakes as observant contributors to the mission.

At the other end of the spectrum lies innovation and research, where little is known about how to obtain a desired result. Creating a movie, a line of original clothing, or a technology that can convert seawater to fuel are all examples. In this context, dramatic failures must be courted and celebrated because they are and integral part of the journey to success. In the middle of the spectrum, where much of the work done today falls, are complex operations, such as hospitals or financial institutions. Here, vigilance and teamwork are both vital to preventing avoidable failures and celebrating intelligent ones.

Reframing failure starts with understanding a basic typology of failure types. As I have written in more detail elsewhere, failure archetypes include preventable failures (never good news), complex failures (still not good news), and intelligent failures (not fun, but must be considered good news because of the value they bring).15 Preventable failures are deviations from recommended procedures that produce bad outcomes. If someone fails to don safety glasses in a factory and suffers an eye injury, this is a preventable failure. Complex failures occur in familiar contexts when a confluence of factors come together in a way that may never have occurred before; consider the severe flooding of the Wall Street subway station in New York City during Superstorm Sandy in 2012. With vigilance, complex failures can sometimes, but not always, be avoided. Neither preventable nor complex failures are worthy of celebration.

In contrast, intelligent failures, as the term implies, must be celebrated so as to encourage more of them. Intelligent failures, like the preventable and complex, are still results no one wanted. But, unlike the other two categories, they are the result of a thoughtful foray into new territory. Table 7.2 presents definitions and contexts to clarify these distinctions. An important part of framing is making sure people understand that failures will happen. Some failures are genuinely good news; some are not, but no matter what type they are, our primary goal is to learn from them.

Table 7.2 Failure Archetypes – Definitions and Implications.16

| Preventable | Complex | Intelligent | |

| Definition | Deviations from known processes that produce unwanted outcomes | Unique and novel combinations of events and actions that give rise to unwanted outcomes | Novel forays into new territory that lead to unwanted outcomes |

| Common Causes | Behavior, skill, and attention deficiencies | Complexity, variability, and novel factors imposed on familiar situations | Uncertainty, experimentation, and risk taking |

| Descriptive Term | Process deviation | System breakdown | Unsuccessful trial |

| Contexts Where Each Is Most Salient |

Production line manufacturing Fast-food services Basic utilities and services |

Hospital care NASA shuttle program Aircraft carrier Nuclear power plant |

Drug development New product design |

Clarifying the Need for Voice

Framing the work also involves calling attention to other ways, beyond failure's prevalence, in which tasks and environments differ. Three especially important dimensions are uncertainty, interdependence, and what's at stake – all of which also have implications for failure (e.g. expectations about its frequency, its value, and its consequences). Emphasizing uncertainty reminds people that they need to be curious and alert to pick up early indicators of change in, say, customer preferences in a new market, a patient's reaction to a drug, or new technologies on the horizon.

Emphasizing interdependence lets people know that they're responsible for understanding how their tasks interact with other people's tasks. Interdependence encourages frequent conversations to figure out the impact their work is having on others and to convey in turn the impact others' work has on them. Interdependent work requires communication. In other words, when leaders frame the work they are emphasizing the need for taking interpersonal risks like sharing ideas and concerns.

Finally, clarifying the stakes is important whether the stakes are high or low. Reminding people that human life is on the line – say, in a hospital, a mine, or at NASA – helps put interpersonal risk in perspective. People are more likely to speak up – thereby overcoming the inherent asymmetry of voice and silence – if leaders frame its importance. Similarly, reminding people that the only thing that is at stake is a bruised ego when a lab experiment doesn't go as hoped is a good way to get them to be willing to go for it – offer possibly crazy ideas and figure out which ones to test first!

Finally, how most people see bosses presents a crucial area for reframing. Table 7.3 compares a set of default frames to a deliberate reframe for how we might think about bosses and others at work. As a default, bosses are viewed as having answers, being able to give orders, and being positioned to assess whether the orders are well executed. With this frame, others are merely subordinates expected to do as they are told. CEO Martin Winterkorn at VW is a prime example of an executive governed by the default frame. Notice that the default set of frames makes interpersonal fear sensible. In a world in which bosses have the answers and absolute authority over how your work is judged, it makes sense to fear the boss and to think very carefully about what you reveal. The reframe, in contrast, spells out logic that clarifies the necessity for a psychologically safe environment. This logic applies to the successful execution of work in most organizations today.

Table 7.3 Framing the Role of the Boss.

| Default Frames | Reframe | |

| The Boss |

Has answers Gives orders Assesses others' performance |

Sets direction Invites input to clarify and improve Creates conditions for continued learning to achieve excellence |

| Others | Subordinates who must do what they're told | Contributors with crucial knowledge and insight |

The reframe shows that leaders must establish and cultivate psychological safety to succeed in most work environments today. The leader is obliged to set direction for the work, to invite relevant input to clarify and improve on the general direction that has been set, and to create conditions for continued learning to achieve excellence. Cynthia Carroll reframed the work at Anglo American by actively inviting the miners' input to draw up new physical safety practices. Naohiro Masuda, the plant superintendent for Fukushima Daini, reframed the work when he set up a whiteboard to lead his team successfully through a tsunami's onslaught. He gave the team as much ongoing information as he had available in a quickly changing environment. The more creativity and innovation are required to achieve a particular goal, the more this stance is needed. The problem with Winterkorn's stance at VW wasn't that it was wrong in a moral sense; rather, it was wrong in a practical sense; it was wrong for achieving a goal that called for innovation. Making the company the largest automaker in the world by leveraging diesel engine technology was somewhat of a “moonshot” goal such as those pursued at Google X. The diesel engine technology was not yet able to perform in ways consistent with regulatory requirements; no amount of giving orders could overcome that basic truth about the situation. A psychologically safe environment, such as we saw at Google X, could have productively absorbed this innovation failure, allowing the senior executives to rethink their strategy.

In the reframe, those who are not the boss are seen as valued contributors – that is, as people with crucial knowledge and insight. When Julie Morath asks people to speak up about patient error or when Eileen Fisher orchestrates staff meetings to give everyone a chance to speak, they do so because it will improve decision-making and execution – not because they want to be nice. Leaders in a volatile, uncertain, complex, and ambiguous (VUCA) world, who understand that today's work requires continuous learning to figure out when and how to change course, must consciously reframe how they think, from the default frames that we all bring to work unconsciously to a more productive reframe.

Framing the work is not something that leaders do once, and then it's done. Framing is ongoing. Frequently calling attention to levels of uncertainty or interdependence helps people remember that they must be alert and candid to perform well. Had NASA leaders emphasized these essential features of the work, the invitation to engineers to share tentative concerns would have been far more visible to them.

Motivating Effort

Emphasizing a sense of purpose is another key element of setting the stage for psychological safety. Motivating people by articulating a compelling purpose is a well-established leadership task. Leaders who remind people of why what they do matters – for customers, for the world – help create the energy that carries them through challenging moments. Kent Thiry's “one for all and all for one” motto motivates staff at DaVita to care for patients with kidney disease. In this motto, he at once reminds people of patients' vulnerability and reminds them that the team is all in it together. Note that even when it seems obvious (for instance, taking care of vulnerable patients) that the work is meaningful, leaders still must take the time to emphasize the purpose the organization serves. This is because anyone can get tired, distracted, and frustrated and lose sight of the larger picture – of what's at stake. Carroll brought her passion for zero harm to the South African government and larger mining institutional bodies. Once stakeholders from previously disconnected groups began working together for the shared goal of safety in the mines they were able to develop trust for one another. It's the leader's job to bring people back to a psychological place where they are in touch with how much their work matters. This also helps the overcome the interpersonal risks they face at work.

Meaning can be defined and framed in other ways, too. Ray Dalio at Bridgewater Associates emphasizes to his hedge fund employees that personal growth is as important as profit. That each employee is becoming a better person matters to Dalio, and he hopes to them as well. Bob Chapman's belief that the company measures success by how well it touches the lives of employees motivates all to bring their best selves to the job.

Most leaders would be well served by stopping to reflect on the purpose that motivates them and makes the organization's work meaningful to the broader community. Having done so, they should ask themselves how often and how vigorously they are conveying this compelling rationale for the work to others. Our primal need to feel purpose and meaning in our lives, including at work, has been demonstrated by numerous studies in psychology.17

How to Invite Participation So People Respond

The second essential activity in the leaders' tool kit is inviting participation in a way that people find compelling and genuine. The goal is to lower what is usually a too-high bar for what's considered appropriate participation. Realizing that self-protection is natural, the invitation to participate must be crystal clear if people are going to choose to engage rather than to play it safe. Two essential behaviors that signal an invitation is genuine are adopting a mindset of situational humility and engaging in proactive inquiry. Designing structures for input, another powerful tool I discuss in this section, also serves as an invitation for voice.

Situational Humility

The bottom line is that no one wants to take the interpersonal risk of imposing ideas when the boss appears to think he or she knows everything. A learning mindset, which blends humility and curiosity, mitigates this risk. A learning mindset recognizes that there is always more to learn.

Frankly, adopting a humble mindset when faced with the complex, dynamic, uncertain world in which we all work today is simply realism. The term situational humility captures this concept well (the need for humility lies in the situation) and may make it easier for leaders, especially those with abundant self-confidence, to recognize the validity, and the power, of a humble mindset. MIT Professor Ed Schein calls this “Here-and-Now Humility.”18 Keep in mind that confidence and humility are not opposites. Confidence in one's abilities and knowledge, when warranted, is far preferable to false modesty. But humility is not modesty, false or otherwise. Humility is the simple recognition that you don't have all the answers, and you certainly don't have a crystal ball. Research shows that when leaders express humility, teams engage in more learning behavior.19

Demonstrating situational humility includes acknowledging your errors and shortcomings. Anne Mulcahy, Chairperson and CEO of Xerox, who led the company through a successful transformation out of bankruptcy in the 2000s, said that she was known to many in the company as the “Master of I Don't Know” because rather than offer an uninformed opinion she would so often reply, “I don't know,” to questions.20 Although reminiscent of Eileen Fisher's “Be a Don't Knower,” Mulcahy adopts this stance as the newly promoted chief executive of a global corporation rather than as a founder of her own company. Speaking to executives in the Advanced Management Program at Harvard Business School, Mulcahy commented that her willingness to be vulnerable with others and admit her own shortcomings turned out to be a huge asset. “Instead of people losing confidence, they actually gain confidence [in you] when you admit you don't know something,” she said.21 This created the space for others at Xerox to step up, offer their expertise, and engage in the process of turning the company around. Although this may seem downright obvious, such humility can be strangely rare in many organizations.

London Business School Professor Dan Cable sheds light on why. In a recent article in Harvard Business Review, he writes, “Power…can cause leaders to become overly obsessed with outcomes and control,” inadvertently ramping up “people's fear – fear of not hitting targets, fear of losing bonuses, fear of failing – and as a consequence…their drive to experiment and learn is stifled.”22 Being overly certain or just plain arrogant can have similar effects – increasing fear, reducing motivation, and inhibiting interpersonal risk taking.

Recall that in our study of neonatal intensive care units mentioned in Chapter 2, Ingrid Nembhard, Anita Tucker, and I found that NICUs with high psychological safety had substantially better results from their quality improvement work than those with low psychological safety.23 A factor we called leadership inclusiveness made the difference. To illustrate, inclusive Medical Directors (physicians in charge of the intensive care organization) said things like, “I may miss something; I need to hear from you.” Others perhaps took it for granted that people knew to speak up. Our survey measure rated three behavioral attributes of leadership inclusiveness: one, leaders were approachable and accessible; two, leaders acknowledged their fallibility; and three, leaders proactively invited input from other staff, physicians, and nurses. The concept of leadership inclusiveness thus captures situational humility coupled with proactive inquiry (discussed in the next section).

Building on this work, Israeli researchers Reuven Hirak and Abraham Carmeli and two of their colleagues surveyed employees from clinical units in a large hospital in Israel on leader inclusiveness, psychological safety, units' ability to learn from failures, and unit performance. They found that units in which leaders were perceived as more inclusive had higher psychological safety, which led to increased learning from failure and better unit performance.24 In sum, leaders who are approachable and accessible, acknowledge their fallibility, and proactively invite input from others can do much to establish and enhance psychological safety in their organizations. Powerful tools, indeed.

Proactive Inquiry

The second tool for inviting participation is inquiry. Inquiry is purposeful probing to learn more about an issue, situation, or person. The foundational skill lies in cultivating genuine interest in others' responses. Why is this hard? Because all adults, especially high-achieving ones, are subject to a cognitive bias called naive realism that gives us the experience of “knowing” what's going on.25 As noted in the previous section, we believe we are seeing “reality” – rather than a subjective view of reality. As a result, we often fail to wonder what others are seeing. We fail to be curious. Worse, many leaders, even when they are motivated to ask a question, worry that it will make them look uninformed or weak. Further exacerbating the challenge, some companies sport “a culture of telling,” as a senior executive in a global pharmaceutical company put it in a recent conversation we had about his company. In a culture of telling, asking gets short shrift.

Yet when leaders overcome these biases to ask genuine questions, it fosters psychological safety. Recall Morath at Children's Hospital: Was everything as safe as you would like it to have been this week with your patients? Or Carroll's question to the mineworkers: What do we need to create a work environment of care and respect? Genuine questions convey respect for the other person – a vital aspect of psychological safety. Contrary to what many may believe, asking questions tends to make the leader seem not weak but thoughtful and wise.

The leaders' tool kit contains a few rules of thumb for asking a good question: one, you don't know the answer; two, you ask questions that do not limit response options to Yes or No, and three, you phrase the question in a way that helps others share their thinking in a focused way. Consistent with these basic principles, the World Café organization, which is dedicated to fostering conversations that focus on finding new ways to accomplish important organizational or social goals, identifies attributes of “powerful questions” – those that provoke, inspire, and shift people's thinking – as shown in the sidebar.

All of us can benefit from introducing more inquiry into our work. The essential skill of inquiry involves picking the right type of question for a situation. For instance, questions can go broad or deep. To broaden understanding of a situation or expand an option set, ask, “what might we be missing?”, “what other ideas could we generate?”, or “who has a different perspective?”27 Such questions ensure that more comprehensive information is considered and that a larger set of options is generated related to a problem or decision. Other questions are designed to deepen understanding. Ask, “what leads you to think so?” or “can you give me an example?” Such questions are crucial to helping people learn about each other's expertise and goals. Moreover, when asked thoughtfully, a good question indicates to others that their voices are desired –instantly making that moment psychologically safe for offering a response.

Bob Pittman, founder of MTV, offers an example of inquiry to push for depth of analysis and diversity of perspective at the same time. In an interview with former New York Times “Corner Office” writer Adam Bryant, Pittman recounts,

Often in meetings, I will ask people when we're discussing an idea, “What did the dissenter say?” The first time you do that, somebody might say, “Well, everybody's on board.” Then I'll say, “Well, you guys aren't listening very well, because there's always another point of view somewhere and you need to go back and find out what the dissenting point of view is.”28

Here we can see that Pittman is practicing proactive inquiry and also modeling to his employees how to do it. Further, the idea that there's always another point of view is a subtle move to frame the work. In this small point, he is framing the work, implicitly reminding the team that creative programming work, such as practiced at MTV, benefits from a diversity of views. For more cases and detail on the power of inquiry as a fundamental leadership skill, I recommend Ed Schein's thoughtful book, Humble Inquiry.29

Designing Structures for Input

A third way to invite participation and reinforce psychological safety is to implement structures designed to elicit employee input. The focus groups and FEA meetings at Children's are examples of such structures. These were so successful in getting conversations on safety underway that hospital staff members began to design structures of their own to elicit their own colleagues' ideas and concerns. Notably, Casey Hooke, a clinical nurse specialist, came up with the idea for a safety action team in her unit. The cross-functional unit-based team met monthly to identify safety hazards in the oncology unit. Soon, two other units, inspired by Hooke's efforts, launched their own safety action teams. Eventually, the patient safety steering committee suggested that all hospital units implement such teams.

Another way to chip away at interpersonal fear is through employee-to-employee learning structures, as Google has done with its creation of the “g2g” (Googler-to-Googler) network, consisting of more than 6000 Google employees who volunteer time to helping their peers learn.30 Participants in g2g do one-on-one mentoring, coach teams on psychological safety, and teach courses in professional skills ranging from leadership to Python coding. Google claims that g2g has helped develop the skills of countless employees. It is also helping to build a psychologically safe culture where everyone is both a learner and a teacher.

The global food company Groupe Danone created structured conference events called “knowledge marketplaces” to foster inquiry and knowledge sharing across country business units.31 Although many good ideas and practices that improved operational performance came out of these workshops, which brought employees from different countries together, the executives who sponsored them saw the most important outcome as a shift in the organizational culture toward speaking up, asking for help, and sharing good ideas.

How to Respond Productively to Voice – No Matter Its Quality

To reinforce a climate of psychological safety, it's imperative that leaders – at all levels – respond productively to the risks people take. Productive responses are characterized by three elements: expressions of appreciation, destigmatizing failure, and sanctioning clear violations.

Express Appreciation

Imagine if Christina, the NICU nurse in Chapter 1, had spoken up to Dr. Drake. Her quiet fear was that he would have berated or belittled her. But what if he had said, “thank you so much for bringing that up”? Her feeling of psychological safety would have gone up a notch. This is an example of an appreciative response. It does not matter whether the doctor believes the nurse's suggestion or question is good or bad. Either way, his initial response must be one of appreciation. Then he can educate – that is, give feedback or explain clinical subtleties. But to ensure that staff keeps speaking up so as to keep patients safe from unexpected lapses in attention or judgment, the courage it takes to speak up must receive the mini-reward of thanks.

Stanford Professor Carol Dweck, whose celebrated research on mindset shows the power of a learning orientation for individual achievement and resilience in the face of challenge, notes the importance of praising people for efforts, regardless of the outcome.32 When people believe their performance is an indication of their ability or intelligence, they are less likely to take risks – for fear of a result that would disconfirm their ability. But when people believe that performance reflects effort and good strategy, they are eager to try new things and willing to persevere despite adversity and failure.

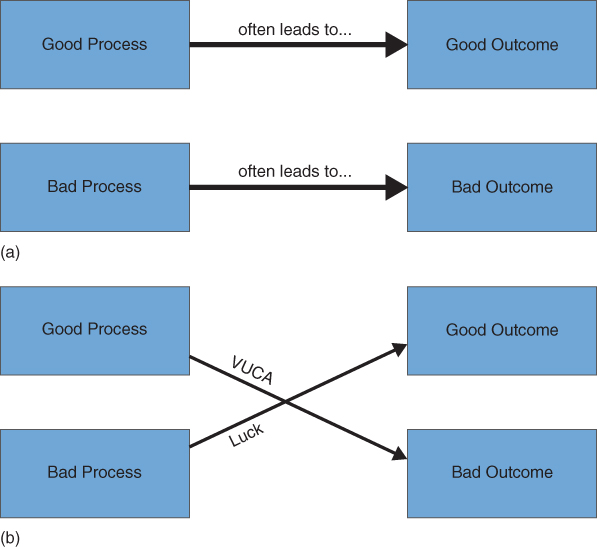

Praising effort is especially important in uncertain environments, where good outcomes are not always the result of good process, and vice versa. Although many of the examples in this book present responses from CEOs, an equally important leadership responsibility for C-level executives is making sure that people throughout the organization respond productively to their colleagues. It helps if everyone understands the logic conveyed in Figure 7.1, which depicts the imperfect relationship between process and outcome. Clearly, good process can lead to good outcomes, and bad process can lead to bad outcomes (Figure 7.1a). But, as shown in Figure 7.1b, good process also can produce bad outcomes (especially facing high uncertainty or complexity, as in VUCA conditions), and bad process can produce a good outcome (when you get lucky), or the illusion of a good outcome (for a while, anyway, as in the cases of VW and Wells Fargo). The lack of simple cause-effect relationships in uncertain, ambiguous environments reinforces the importance of productive responses to outcomes of all kinds, but especially to bad news outcomes.

Figure 7.1 The Imperfect Relationship between Process and Outcome.

Productive responses often include expressions of appreciation, ranging from the small (“thank you so much for speaking up”) to the elaborate – celebrations or bonuses in response to intelligent failure.

Destigmatize Failure

Failure is a necessary part of uncertainty and innovation, but this must be made explicit to reinforce the invitation for voice. Consider the implications of the failure typology in Table 7.2 for designing a productive response to news of a failure. Leaders who respond to all failures in the same way will not create a healthy environment for learning. When a failure occurs because someone violated a rule or value that matters in the organization, this is very different than when a thoughtful hypothesis in the lab turns out to be wrong. Although obvious in concept, in practice people routinely get this wrong.

I frequently ask managers, scientists, salespeople, and technologists around the world the following question: What percent of the failures in your organizations should be considered blameworthy? Their answers are usually in single digits – perhaps 1% to 4%. I then ask what percent are treated as blameworthy. Now, they say (after a pause or a laugh) 70% to 90%! The unfortunate consequence of this gap between simple logic and organizational response is that many failures go unreported and their lessons are lost. As shown in Table 7.4, the primary result of responding to failures in a negative way is that you don't hear about them. And that, as Mark Costa noted in Chapter 2, should be your biggest fear.

Table 7.4 Destigmatizing Failure for Psychological Safety.

| Traditional Frame | Destigmatizing Reframe | |

| Concept of Failure | Failure is not acceptable. | Failure is a natural by-product of experimentation. |

| Beliefs About Effective Performance | Effective performers don't fail. | Effective performers produce, learn from and share the lessons from intelligent failures. |

| The Goal | Prevent failure. | Promote fast learning. |

| The Frame's Impact | People hide failures to protect themselves. | Open discussion, fast learning, and innovation. |

A productive response to a complex failure at Children's Hospital is embodied in the FEA process, described in the Leader's Tool Kit section. All of the people whose work or role touched the failure in question are invited to sit around the same table to share their observations, their questions, and their concerns related to the events that unfolded. Everyone listens intently to what others saw, felt, and did. More often than not, individuals were doing their tasks in prescribed ways, but a host of factors came together in a new way to produce a mishap. The FEA is not a fun activity, but it is deeply meaningful and gratifying. People gain understanding of how various systems and roles in the hospital intersect, and they leave with a deeper appreciation of system complexity and interdependence. They do not feel blamed but instead empowered to go back out and make the system better so as to prevent a similar failure in the future. Most importantly, they feel psychologically safe enough to keep reporting what they see, to keep asking for help or clarification, and to offer ideas for improvement.

In fact, a productive response to intelligent failure can mean actually celebrating the news. Some years ago, the chief scientific officer at Eli Lilly introduced “failure parties” to honor intelligent, high-quality scientific experiments that failed to achieve the desired results.33 Might this be a bridge too far? I don't think so. First, and most obvious, it helps build a psychologically safe climate for thoughtful risks, which is mission critical in science. Second, it helps people acknowledge failures in a timely way, which allows redeployment of valuable resources – scientists and materials – to new projects earlier rather than later, potentially saving thousands of dollars. Third, when you hold a party, people tend to show up – which means they learn about the failure. This in turn lowers the risk that the company will repeat the same failure. An intelligent failure the first time around no longer qualifies as intelligent the second time.

In brief, a productive response to preventable failures is to double down on prevention, usually a combination of training and improved system design to make it easier for people to do the right thing. However, there are instances in which a preventable failure is the result of a blameworthy action or a repeated instance of deviation from prescribed process, impervious to prior attempts at redirection. In such cases, usually rare, there is an obligation to act in ways that prevent future occurrence. This may mean fines or other sanctions, and in some cases even firing someone.

Sanction Clear Violations

Yes, firing can sometimes be an appropriate and productive response –to a blameworthy act. But won't this kill the psychological safety? No. Most people are thoughtful enough to recognize (and appreciate) that when people violate rules or repeatedly take risky shortcuts, they are putting themselves, their colleagues, and their organization at risk. In short, psychological safety is reinforced rather than harmed by fair, thoughtful responses to potentially dangerous, harmful, or sloppy behavior.

In July 2017, Google engineer James Damore wrote a 10-page memo railing against the company's diversity stance, arguing that biological differences explained why Google had fewer women engineers and paid them less well than men, and circulated it widely within the company.34 Someone then leaked the memo, creating a public firestorm.35

How did Google respond? Damore was promptly and publicly fired a month later, earning the company both praise and criticism. Thoughtful arguments have been made on both sides of the firing debate. Rather than coming out on one side or the other, let's step back to consider when firing constitutes a “productive response,” and when it doesn't.

Take this specific case. To begin, it is a shame that Damore chose to share his personal concerns electronically and widely within the company, all but ensuring that someone who disliked the memo would share it publicly. Ideally, an employee with an opinion to express related to an important work issue or policy would first solicit feedback from colleagues, especially with those who might be likely to have a different view. The person might want to first learn more about the potential impact of those ideas and the forms in which they could be expressed. Very few of us are able to see complex issues from multiple perspectives and consider the potential consequences well enough to make good decisions about them alone. This doesn't matter when stakes are low. But stakes are high when a document that affects your colleagues, customers, or company may be read by millions.

But, once the inflammatory memo has been made public, how should a company respond? My intention is not to illuminate the specifics of Damore's memo at Google but rather to suggest a general strategy for productive responses to actions or events in your organization that you wish had not occurred.

If there are clear policies against the use of company email addresses or social media platforms for the expression of personal opinions, then an employee who violates these policies commits what we can call a blameworthy act. In this case, a productive response indeed involves tough sanctions, which may include terminating the employee. A tough response is productive because it lets people know that the company is serious about its policies and values, which shapes future behavior, and because it constitutes a fair response to a stated violation.

If policies are unclear, however, a productive response is one that turns the unfortunate event into a different kind of learning opportunity – for the company and sometimes for the interested public. In the Damore case, executives might express dismay at the employee's opinion (and perhaps dismay at his ignorance of a larger set of societal forces that have systematically diminished advancement opportunities for certain demographic groups over decades). They might then go on to explain their plans for educating employees on what they believe to be the value of a diverse workforce. As part of this organizational learning process, company managers at all levels would elicit and listen to ideas, questions, concerns, and frustrations. They might create opportunities for engaging in perspective taking, building empathy, developing inquiry skills, and more. The organization might also seek ways to come up with new, improved ways to leverage employee diversity to build better products and services.

In short, a productive response is concerned with future impact. Punishment sends a powerful message, and an appropriate one if boundaries were clear in advance. Indeed, it is vital to send messages that reinforce values the company holds dear. However, it is equally vital not to inadvertently send a message that says, “diverse opinions simply won't be tolerated here,” or “one strike and you're out.” Such messages reduce psychological safety and ultimately erode the quality of the work. In contrast, a message that reinforces the values and practices of a learning organization is, “it's okay to make a mistake, and it's okay to hold an opinion that others don't like, so long as you are willing to learn from the consequences.” The most important goal is figuring out a way to help the organization learn from what happened. And so, if there is ambiguity about public self-expression related to company policies, then a productive response is one that engages people in a learning dialogue to better understand and improve how the company functions. Table 7.5 shows how a productive response to failure in an organization should vary for different failure types.

Table 7.5 Productive Responses to Different Types of Failure.

| Preventable Failure | Complex Failure | Intelligent Failure | |

| Productive Response |

|

|

|

Leadership Self-Assessment

The practices described in this chapter are dominated by complex interpersonal skills and thus not easy to master. They take time, effort, and practice.36 Perhaps the most important aspect of learning them is to practice self-reflection. A set of self-assessment questions, provided in a sidebar, can be used to do just that. The questions map to and operationalize the framework introduced in this chapter.

Endnotes

- Wakabayashi, D. “Contentious Memo Strikes Nerve Inside Google and Out.” The New York Times. August 8, 2017. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/08/08/technology/google-engineer-fired-gender-memo.html Accessed June 14, 2018.

- Molteni, M. & Rogers, A. “The Actual Science of James Damore's Google Memo.” WIRED. August 15, 2017. https://www.wired.com/story/the-pernicious-science-of-james-damores-google-memo/ Accessed June 14, 2018.