2

The Paper Trail

“Your greatest fear as a CEO is that people aren't telling you the truth.”

—Mark Costa1

Mark Costa, CEO of Eastman Chemical Company, was speaking to a classroom full of second-year MBA students at the Harvard Business School in the late spring of 2018. The students were paying unusually close attention; there was something about his confidence, his energy – and indeed his taking the time to share his insights with them – that exuded “role model.” An alumnus of the school, Costa had spent many years in strategy consulting before taking an executive role at Eastman – from which he was later promoted to run the company. Now four years into his tenure as CEO, he clearly relished both the opportunity and the responsibility of leading the $10 billion-dollar global specialty chemical manufacturer headquartered in Kingsport, Tennessee. Under Costa's leadership, the portion of sales accounted for by innovative specialty products rather than commodity products had steadily risen, consistent with a crucial strategic goal he'd articulated for the company. Financial performance was correspondingly strong. To accomplish this, engaging the expertise, ideas, and market knowledge of Eastman's 15 000 employees around the world had been mission critical.

For the benefit of the students for whom diplomas and new jobs were imminent, Costa reflected on what he had learned in the quarter century since he'd graduated from business school. As the quote at the opening of the chapter conveys, he stated – likely surprising many of them – that his greatest fear as CEO was of not knowing what's really going on. He worked hard to make it clear to his employees that he wanted the truth—good, bad, ugly, or disappointing. He explained to the class that, as a leader, you have to “be willing to be vulnerable and be open about your mistakes so others feel safe” to report their own.2 Alluding to the risk of hubris, Costa added, “If you think you have all the answers, you should quit. Because you're going to be wrong.”3

In today's organizations, psychological safety is not a “nice-to-have.” It's not an employee perk, like free lunch or game rooms, that you might care about so as to make people happy at work. In contrast, I'll argue that psychological safety is essential to unleashing talent and creating value. Hiring talent simply isn't enough anymore. People have to be in workplaces where they are able and willing to use their talent. In any organization that requires knowledge – and especially in one that requires integrating knowledge from diverse areas of expertise – psychological safety is a requirement for success. In short, when companies rely on knowledge and collaboration for innovation and growth, whether or not to invest in building a climate of psychological safety is no longer a choice. Every manager must follow Mark Costa's lead.

Not a Perk

In any company confronting conditions that might be characterized as volatility, uncertainty, complexity, and ambiguity (VUCA), psychological safety is directly tied to the bottom line. This is because employee observations, questions, ideas, and concerns can provide vital information about what's going on – in the market and in the organization. Add to that today's growing emphasis on diversity, inclusion, and belonging at work, and it becomes clear that psychological safety is a vital leadership responsibility. It can make or break an employee's ability to contribute, to grow and learn, and to collaborate.

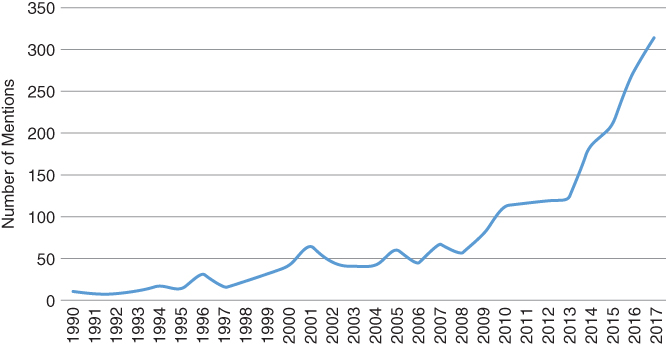

One measure of practitioner interest in psychological safety can be found in the term's use frequency in the popular media. To gauge the popularity of the concept, I used Factiva to see how many times the term had been mentioned in newspapers, articles, blogs, and other news media. The graph in Figure 2.1 depicts the results, indicating mentions of “psychological safety” and its variants (i.e. psychologically safe) each year since 1990.

Figure 2.1 Mentions of Psychological Safety in Popular Media.4

The uptick in mentions in recent years reflects, I believe, growing recognition that psychological safety matters in any environment in which people are attempting to do something novel or challenging. From leading a project team in the office5 to caring for patients in the hospital ward,6 from coaching a cricket squad on the pitch7 to teaching and counseling young students at school,8 from encouraging others to speak out about wrong-doing9 to even reaching Mars(!),10 psychological safety is essential for communicating, collaborating, experimenting, and ensuring the well-being of others in a wide variety of team and organizational settings.

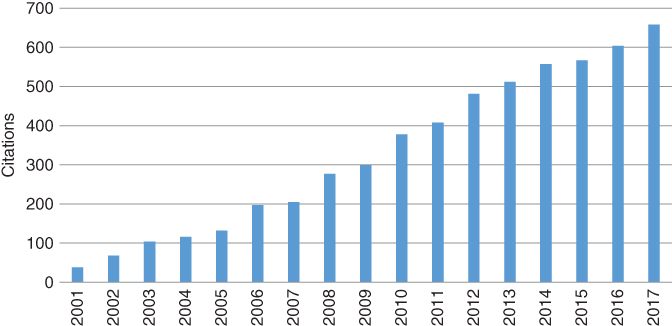

Another measure of interest on the part of researchers can be found in academic citations to the article that introduced the concept and measure of team psychological safety.11 As shown in Figure 2.2, the article has been frequently cited, with each year since its publication in 1999 showing more citations than the year before. This is a quick and simple index of the degree to which academic research has found that the psychological safety variable explains outcomes of interest.

Figure 2.2 Citations of 1999 Article Introducing Team Psychological Safety.12

This chapter reviews the evidence for psychological safety's benefits from two decades of research, laying the foundation for the real-world stories of low and high psychological safety workplaces that lie ahead in Part II. Over the past 20 years, scholars, consultants, and company insiders have published dozens of rigorous studies showing effects of psychological safety in a variety of industry settings. By sharing some of the highlights, I hope to give the reader confidence in the importance of psychological safety in the modern workplace. My hope is that knowing that the ideas and stories in this book are backed up by data will motivate many readers to act on this knowledge.

The Research

My colleagues and I reviewed the academic literature on psychological safety. We were surprised by the number of studies we found and by the range of settings in which psychological safety has been examined. Studies conducted in companies, government organizations, nonprofits, school systems, hospitals, and classrooms highlight the growing cross-sector interest in psychological safety.

Reading more than 100 articles, we found plenty of evidence that psychological safety matters. It affects measurable outcomes ranging from employee error reporting13 to company return on investment.14 Unfortunately, the research also makes clear that many workplaces lack psychological safety, cutting themselves off from the kinds of employee input, engagement, and learning that are so vital to success in a complex and turbulent world.

I organized the studies into five categories. Group 1 reveals the extent to which psychological safety is lacking in many workplaces. Group 2, which is the largest, investigates relationships between psychological safety and learning. In these studies, we find the evidence that psychological safety leads to, among others, creativity, error reporting, and knowledge sharing, as well as behaviors that detect the need for change or that help teams and organizations make change. Group 3 finds positive relationships between psychological safety and performance, and Group 4 finds positive relationships between psychological safety and employee engagement.

Lastly, Group 5 encompasses what researchers call “moderator studies,” in which psychological safety alters a relationship between another team attribute and an outcome, such as team performance. A team attribute might be diverse expertise, which would naturally challenge the team to figure out how to work effectively. Similarly, a team with members located in multiple geographic regions might struggle to coordinate. Studies show that psychological safety makes it easier for teams to manage such challenges. When people can speak up, ask questions, and get the help they need from each other to sort things out, they are more likely to overcome the barriers created by working together across diverse disciplines or time zones.

1. An Epidemic of Silence

Chances are you've had the experience at work when you did not ask a question you really wanted to ask. Or you may have wanted to offer an idea but stayed quiet instead. Several studies show that these types of silence are painfully common. Collecting and analyzing data from interviews with employed adults, studies have investigated when and why people feel unable to speak up in the workplace. From this work we learn, first and foremost, that people often hold back even when they believe that what they have to say could be important for the organization, for the customer, or for themselves.

There is a poignancy in these discoveries. No one gains from the silence. Teams miss out on insights. Those who fail to speak up often report regret or pain. Some wish they had spoken up. Others recognize they could be experiencing more fulfillment and meaning in their jobs were they more able to contribute. Those deprived of hearing a colleague's comments may not know what they are missing, but the fact is that problems go unreported, improvement opportunities are missed, and occasionally, tragic failures occur that could have been avoided.

In an early study of workplace silence, New York University management researchers Frances Milliken, Elizabeth Morrison, and Patricia Hewlin interviewed 40 full-time employees working in consulting, financial services, media, pharmaceuticals, and advertising, to understand why employees failed to speak up at work and what issues they failed to raise most often.15 When pressed to explain why they remained silent, people often said they did not want to be seen in a bad light. Another common reason was not wanting to embarrass or upset someone. Still others expressed a sense of futility – along the lines of, “it won't matter anyway; why bother?” A few mentioned fear of retaliation. But the two most frequently mentioned reasons for remaining silent were one, fear of being viewed or labeled negatively, and two, fear of damaging work relationships. These fears, which are definitionally the opposite of psychological safety, have no place in the fearless organization.

What issues employees wanted to speak up about were both organizational and personal. They ranged from concerns that are understandably difficult to raise: for example, about harassment, a supervisor's competence, or having made a mistake. More surprisingly, however, they also held back on suggestions for improving a work process. In short, as later research would demonstrate more systematically, people at work are not only failing to speak up with potentially threatening or embarrassing content, they are also withholding ideas for improvement. Notably, every individual interviewee reported failing to speak up on at least one occasion. Most had found themselves in situations where they were very concerned about an issue and yet still did not raise it to a supervisor.

A later and larger study conducted in a manufacturing company used survey data to identify very similar reasons for silence.16 Specifically, employees who did not feel psychologically safe to speak up cited reasons that included fear of damaging a relationship, lack of confidence, and self-protection. In another study, social psychologist Renee Tynan surveyed business school students about their relationships with a prior boss to gain insight into when and why people do (or don't) communicate their thoughts upward. She found that when people felt psychologically safe, they spoke up to their bosses. They were able to ask for help and admit errors, despite interpersonal risk. When they did not feel psychologically safe, they tended to keep quiet or to distort their message so as not to upset their bosses.

A few years ago, University of Virginia Professor Jim Detert and I interviewed more than 230 employees in a large multinational high-tech company.17 We asked interviewees, who spanned all levels, regions, and functions, to describe instances in which they did and did not speak up at work to their managers or anyone else higher in the company. Here too, all individuals could readily describe a time in which they failed to speak up about something they believed mattered. Jim and I combed through the thousands of pages of accumulated responses to find out what drove people to speak up – and, perhaps more importantly, what drove them to hold back.

Consider the manufacturing technician in a US plant who told us he didn't share an idea he had for speeding up the production process. When we asked why, he replied, “I have kids in college.” At first glance, a nonsensical reply. But his meaning was clear; he felt he could not take the risk of speaking up because he could not afford to lose his job. When we probed further, hoping to hear a story about someone losing a job related to speaking up, the associate admitted that it really didn't work that way. In fact, he replied, “Oh, everyone knows we never fire anybody.” He was not speaking sarcastically; he was admitting that his reticence to rock the boat with what he believed was a good idea was irrational, and deep down he understood that. Yet the gravitational pull of silence – even when bosses are well-meaning and don't think of themselves as intimidating – can be overwhelming. People at work are vulnerable to a kind of implicit logic in which safe is simply better than sorry. Many have simply inherited beliefs from their earliest years of schooling or training. If they stop to think more deeply, they may realize they've erred too far on the side of caution. But that kind of reflection is rarely prompted.

Ultimately, we discovered a small set of common, largely taken-for-granted beliefs about speaking up at work. We called them implicit theories of voice. Shown in Table 2.1, they are essentially beliefs about when it is and isn't appropriate to speak to higher ups in an organization. To test these implicit theories, gleaned from one company, Jim and I conducted a vignette study with managers from many other companies. We designed fictional vignettes to test when and if people would employ specific decision rules in determining whether or not to speak up. For example, one vignette involved an important correction an employee wanted to share with the boss; in one of the versions of the vignette, the boss's boss was present. In the other vignette, only the boss was present. The managers we studied were significantly more likely to point out the correction if the boss's boss was not present.

Table 2.1 Taken-for-granted Rules for Voice at Work.

| Taken-for-granted Rule Governing when to Speak or Remain Silent | Examples from Interviews |

| Don't criticize something the boss may have helped create. |

“It's inherently risky since bosses may feel personal ownership of the tasks I am suggesting are problematic.” “The boss may have created these processes and may be offended because he's attached to them.” |

| Don't speak unless you have solid data. |

“I think that presenting an under-developed, under-researched idea is never a good idea.” “You are questioning their ideas and had better have proof to back up your statements.” |

| Don't speak up if the boss's boss is present. |

“If there is a higher level individual present it is risky because you would be afraid that your direct boss would feel as if you were going over their head.” “My boss would see [speaking up to his boss] as undermining and insubordinate.” |

| Don't speak up in a group with anything negative about the work to prevent boss from losing face. |

“Managers hate to be put on the spot in front of others. It is best to brief them one-on-one so the boss doesn't look bad in front of the group.” “You should pass it by the boss in private first, so you don't ‘cut his legs out from under him.’” |

| Speaking up brings career consequences. |

“To stop or criticize a project would be a career ender at our place.” “The long-term consequences are bad because [higher ups] will resent being put on the spot.” |

By and large, these beliefs (taken-for-granted rules) about speaking up make it harder to achieve productivity, innovation, or employee engagement. It's an old truism that bad news doesn't travel up the hierarchy. But what we found is that people err so far on the side of caution at work that they routinely hold back great ideas – not just bad news. They intuitively recognize what Jim and I call the asymmetry of voice and silence. Consider the automatic calculus that governs speaking up. As depicted in Table 2.2, voice is effortful and might (but might not) make a real difference in a crucial moment. Unfortunately, much of the time the potential benefit will take a while to materialize and might not even happen at all. Silence is instinctive and safe; it offers self-protection benefits, and these are both immediate and certain.

Table 2.2 Why Silence Wins in the Voice-Silence Calculation.

| Who Benefits | When Benefit Occurs | Certainty of Benefit | |

| Voice | The organization and/or its customers | After some delay | Low |

| Silence | Oneself | Immediately | High |

Another way to think about the voice-silence asymmetry is captured in the phrase “no one was ever fired for silence.” The instinct to play it safe is powerful. People in organizations don't spontaneously take interpersonal risks. We don't want to stumble into a sacred cow. We can be completely confident that we'll be safe if we are silent, and we lack confidence that our voices will really make a difference – a voice inhibiting combination.

Another of the implicit theories of voice that Jim and I found that explains why people hold back on good ideas, not just bad news, is related to a fear of insulting someone higher up in the organization by implying that the current systems or processes are problematic. What if the current system is effectively the boss's baby? By suggesting a change, we might be calling the boss's baby ugly. Better to stay silent.

In failing to challenge these widely held taken-for-granted speaking rules, employees around the world at this particular company (which, ironically, was dependent on employee expertise and ideas for its future success) were depriving their colleagues of their ideas and ingenuity. They were depriving themselves as well – missing out on the satisfaction of the chance to act on their ideas and create change. Instead of helping to create a learning organization, they were just showing up and doing their jobs.

2. A Work Environment that Supports Learning

Given this well-documented tendency for people in the workplace to choose silence over voice, sometimes it seems surprising that anyone ever speaks up at all with potentially sensitive or interpersonally threatening content. This is where psychological safety comes in. A growing number of studies find that psychological safety can exist at work and, when it does, that people do in fact speak up, offer ideas, report errors, and exhibit a great deal more that we can categorize as “learning behavior.”

Learning from Mistakes

For example, in a study of nurses in four Belgian hospitals, a team of researchers led by Hannes Leroy explored how head nurses encouraged other nurses to report errors, while also enforcing high standards for safety.18 The challenge here is one of asking people to perform the highest quality (arguably, error-free) work yet still be willing to talk about the errors that do occur. Leroy and his colleagues surveyed the nurses in 54 departments, measuring a set of interrelated factors. These were psychological safety, error reporting, the actual number of errors made, and nurses' beliefs about how much the department prioritized patient safety and about whether the head nurse practiced the safety protocols.

Leroy found that groups with higher psychological safety reported more errors to head nurses. That finding was consistent with what I had seen back in graduate school in my study of medication errors.19 More interestingly, they found that when nurses thought patient safety was a high priority in the department and when psychological safety was high, fewer errors were made. In contrast, when psychological safety was low, despite believing in the department's professed commitment to patient safety, staff made more errors. In short, psychologically safe teams made fewer errors and spoke up about them more often. What I have found in similar settings is that good leadership (for instance, on the part of head nurses who demonstrate a commitment to safety and to openness), together with a clear, shared understanding that the work is complex and interdependent, can help groups build psychological safety, which in turn enables the candor that is so essential to ensuring the quality of patient care in modern hospitals.

Quality Improvement: Learn-What and Learn-How

Nearly every organization wants quality improvement. Hospitals, especially, constantly pursue efforts to improve the innumerable processes of patient care. Does it make a difference whether a unit supervisor creates the conditions for psychological safety or simply commands staff to work on improvement projects?

With Wharton Professor Ingrid Nembhard and Boston University Professor Anita Tucker, I studied over a hundred quality improvement (QI) project teams in neonatal intensive care units (NICUs) in 23 North American hospitals.20 By asking the QI team members to report on what they did to improve unit processes, we found that these clustered into two distinct sets of learning behavior, which we called learn-what and learn-how. Learn-what described largely independent activities like reading the medical literature to get caught up with the latest research findings. Learn-how, in contrast, was team-based learning that included sharing knowledge, offering suggestions, and brainstorming better approaches.

We were intrigued to find that psychological safety predicted an uptick in learn-how behaviors (those that came with interpersonal risk) but had no statistical relationship whatsoever with the more independent behaviors captured by learn-what activities. This result provided a reassuring demonstration that psychological safety does promote learning by helping people overcome interpersonal risk for engaging in learn-how behaviors. Not surprisingly, for the kinds of learning that you can do alone (read a book, take an online course), psychological safety is not essential. The results also offer support for why psychological safety was not as important in days of yore when work might consist primarily of well-defined tasks such as typing letters for the boss, or passing the surgeon the correct scalpel.

Reducing Workarounds

“Workarounds,” a phenomenon identified by Anita Tucker in her remarkable ethnographic study of nurses in the early 2000s, are shortcuts that people take at work when they confront a problem that disrupts their ability to carry out a required task.21 A workaround accomplishes the immediate goal, but does nothing to diagnose or solve the problem that triggered the workaround in the first place.

The problem with workarounds is that well they, work. They seem to get the job done, but, in so doing, they create new, subtle, problems. First, workarounds sometimes create unintended risks or problems in other areas. For example, confronted with a shortage of a needed material input (say, linens in a hospital unit), a worker might simply find a supply of linens in another unit, thereby getting what she needs but depleting her colleagues who will encounter a shortage later. Second, workarounds delay or prevent process improvement. The problems that trigger workarounds can be seen as small signals of a need for change in a system or process. The workaround bypasses the problem, thereby silencing the signal by getting the immediate job done – but getting it done in a way that is inefficient over the longer term. More difficult, because it would require working across silos, would be for nurses to devise a new linen supply system for all units.

Workarounds can occur when workers do not feel safe enough to speak up and make suggestions to improve the system. Indeed, in another study of hospitals, Jonathon Halbesleben and Cheryl Rathert found that cancer teams with low psychological safety relied more on workarounds, while teams with high psychological safety focused more on diagnosing the problem and improving the process that caused it so it didn't happen again.22 Halbesleben and Rathert gave us additional evidence that psychological safety is important for organizations interested in achieving process improvement. Their work shows that psychological safety makes it easier for people to speak up about problems and to alter and improve work processes rather than engaging in the counterproductive workarounds.

Another study of process improvement projects, this time in a manufacturing company, also found that projects with greater psychological safety were more successful. Here the researchers studied 52 process-improvement teams following principles of total quality management (TQM). They found that even when employing a highly-structured process improvement technique, interpersonal climate matters for success.23

Sharing Knowledge When Confidence Is Low

You might think that speaking up with creative ideas is easier than speaking up about errors. Now, imagine you're at work and you've got an idea you're 95% confident is creative or interesting. You'll probably have no trouble speaking up. Now imagine that same situation but you're only 40% confident of your idea. Most people will hesitate, perhaps trying to size up the receptivity of their colleagues. Stated another way, when you feel extremely confident in the value or veracity of something you want to say, you are more likely to simply open your mouth and say it. But when your confidence in your idea or your knowledge is low, you might hold back.

In a particularly compelling study in several US manufacturing and service companies, University of Minnesota Professor Enno Siemsen and his colleagues found an intuitively interesting relationship between confidence and psychological safety.24 As expected, the more confident people were in their knowledge, the more they spoke up. More interestingly, a psychologically safe workplace helped people overcome a lack of confidence. In other words, if your workplace is psychologically safe, you're more able to speak up even when you have less confidence. Given that an individual's confidence and the value of his idea are not always tightly linked, the usefulness of psychological safety for facilitating knowledge sharing can be immense. Communication frequency among coworkers also led to psychological safety. In other words, the more we talk to each other, the more comfortable we become doing so.

3. Why Psychological Safety Matters for Performance

To understand why psychological safety promotes performance, we have to step back to reconsider the nature of so much of the work in today's organizations. With routine, predictable, modular work on the decline, more and more of the tasks that people do require judgment, coping with uncertainty, suggesting new ideas, and coordinating and communicating with others. This means that voice is mission critical. And so, for anything but the most independent or routine work, psychological safety is intimately tied to freeing people up to pursue excellence.

When I set out to study 50 teams – including sales, production, new product development, and management teams – in a manufacturing company in the mid 1990s, my goal had been to establish a relationship between psychological safety and learning behavior. While I was at it, I measured performance. I did this in two ways: The first was self-report, meaning team members confidentially rated their team's performance on a scale of one to seven. The other was somewhat more objective. I asked managers who evaluated the team's work, along with (internal) customers who received the work, to rate each team's performance on a similar scale, also with complete confidentially. Happily, the data showed that teams with psychological safety also had higher performance – a result that held for both types of performance measures.25

Researchers Markus Baer and Michael Frese took this question up to the next level of analysis by showing that psychological safety increased company performance in a sample of 47 mid-size German firms in both industrial and services industries. Performance was measured in two ways: longitudinal change in return on assets (holding prior return on assets constant) and executive ratings of company goal achievement.26 All of the companies were engaged in process innovations. But process innovation efforts only led to higher performance when the organization had psychological safety. In short, process innovation can be a good way to boost firm performance, but a psychologically safe environment helps the investment pay off.

Research also shows a relationship between psychological safety and innovation. For instance, Chi-Cheng Huang and Pin-Chen Jiang collected survey data from 245 members of 60 Research and Development (R&D) teams in several Taiwanese technology firms and found that psychologically safe teams outperformed others.27 Without psychological safety, the researchers explained, team members were unwilling to offer their ideas or knowledge because of the fear of being rejected or embarrassed. They emphasized the particular importance of psychological safety for teams in R&D because they necessarily have to take risks and confront failure before they achieve success.

Finally, a multi-year study of teams at Google, code-named Project Aristotle, found that psychological safety was the critical factor explaining why some teams outperformed others, as reported in a detailed feature article by Charles Duhigg in the New York Times Magazine in 2016, and widely discussed in the blogosphere.28 Google researchers from the company's sophisticated “people analytics” group reviewed the academic literature on team effectiveness. Their first line of attack was to consider team composition – a variable considered important in historical research on teams, primarily in terms of whether the skills team members hold are a good match for the work they're expected to do.

Led by Julia Rozovsky, the researchers considered people's educational backgrounds, hobbies, friends, personality traits and more, in their analysis a set of 180 teams from all over the company. They found nothing. No mix of personality types or skills or backgrounds emerged that helped explain which teams performed well and which didn't. It seemed like there was no answer to the question of why some teams thrive and others fail. And then, as Duhigg wrote, “When Rozovsky and her Google colleagues encountered the concept of psychological safety in academic papers, it was as if everything suddenly fell into place.”29 What they had discovered was that even the extremely smart, high-powered employees at Google needed a psychologically safe work environment to contribute the talents they had to offer. The team also found four other factors that helped explain team performance – clear goals, dependable colleagues, personally meaningful work, and a belief that the work has impact. As Rozovsky put it, however, reiterating the quote at the start of Chapter 1, “psychological safety was by far the most important…it was the underpinning of the other four.”30

4. Psychologically Safe Employees Are Engaged Employees

Executive interest in employee engagement has taken hold in recent years, building on the longtime focus on employee satisfaction as an important measure for predicting turnover. Today, most managers understand that employee satisfaction is important but incomplete. Satisfaction, which refers to how happy or content employees are, doesn't capture emotional commitment to the work, or motivation to pour oneself into doing a good job. Engagement, defined as the extent to an employee feels passionate about the job and committed to the organization, is seen as an index of willingness to put discretionary effort into one's work. Validated measures of employee engagement are widely available, and most executives recognize employee engagement as a vital element of strong company performance.

Recent studies of employee engagement include attention to psychological safety. For instance, a study in a Midwestern insurance company found that psychological safety predicted worker engagement. In turn, psychological safety was fostered by supportive relationships with coworkers.31 Another study looked at the relationship between employee trust in top management and employee engagement. With survey data from 170 research scientists working in six Irish research centers, the authors showed that trust in top management led to psychological safety, which in turn promoted work engagement.32 Finally, a study of Turkish immigrants employed in Germany found that psychological safety was associated with work engagement, mental health, and turnover intentions. Moreover, they found that the positive effects of psychological safety were higher for the immigrants than for the German employees in the same company.33

One place where worker engagement really matters is healthcare delivery. Frontline staff confront high stress and emotionally laden work with life and death consequences. Disengaged employees lead to safety risks and to staff turnover. Turnover means higher recruiting and training costs, as well as a higher percentage of less experienced workers on staff. Experts' concerns about staff turnover have thus given rise to interest in improving the healthcare work environment as a strategy for employee retention. In one recent study, a survey of clinical staff at a large metropolitan hospital found that psychological safety was related to commitment to the organization and to patient safety. The authors noted that a work environment in which workers felt safe to speak up about problems was especially important in healthcare for helping people feel able to provide safe care and stay engaged in the work.34

5. Psychological Safety as the Extra Ingredient

The fifth and final group of studies emphasizes psychological safety's role in altering the strength of relationships between other variables. In these studies, psychological safety acts (using statistical language) as a moderator that makes other relationships weaker or stronger. Psychological safety has been found to help teams overcome the challenges of geographic dispersion, put conflict to good use, and leverage diversity.

Overcoming Geographic Dispersion

It's increasingly common for teams to have members working in different locations around the world who may not even have met in person. These so-called virtual teams face the related challenges of communicating through electronic media, managing national cultural diversity, coping with time zone differences, and dealing with shifting membership over time. Psychological safety has been shown to help such teams manage these challenges. For instance, in an ambitious study of 14 innovation teams with members dispersed across 18 nations, University of Western Australia Professor Cristina Gibson and Rutgers University Professor Jennifer Gibbs showed that psychological safety helped these dispersed teams navigate the challenges of dispersion.35 With psychological safety, team members felt less anxious about what others might think of them and were better able to communicate openly.

Putting Conflict to Good Use

Conflict is another challenge most teams confront – whether they work face to face or spread around the globe. In theory, conflict promotes better decision-making and fosters innovation because it ensures consideration of diverse views and perspectives. In practice, however, people are not always good at navigating conflict and putting it to good use.36 It's easy to get upset or dig in one's heels, effectively squandering the opportunity to improve the work by working through differences. Some recent research has found that psychological safety can make the difference between conflict being put to good use and conflict getting in the way of team performance. For instance, in a study of 117 student project teams, Bret Bradley and his colleagues showed that psychological safety moderated the relationship between conflict and performance such that conflict led to good team performance when teams had high psychological safety and low performance otherwise.37 They attributed this result to the ability to express relevant ideas and critical discussion without embarrassment or excessive personal conflict between team members.

As you can see, studies that look at psychological safety have been done in many settings, including factories, hospitals, and classrooms. Yet it is also the case that executives wrestling with strategic decisions can benefit from attention to creating a climate of curiosity and candor – in other words, psychological safety. When I studied top management teams with action scientist Diana Smith, we analyzed detailed transcripts of their conversations to show how a psychologically safe climate for candid discussion of strategic disagreement can be created, even in high-level teams confronting strategic challenges, and how this can enable productive decision-making.38

Gaining Value from Diversity

Teams are often put together to leverage diverse expertise. But too often, the challenge of integrating diverse knowledge, perspectives, and skills is underestimated, and the hoped-for synergy never materializes. One recent study showed that psychological safety can make or break achievement of team performance in diverse teams. The researchers surveyed master's students participating in 195 teams in a French university and found that expertise-diverse teams performed well when psychological safety was high and badly otherwise.39

Finally, a number of studies have investigated effects of demographic diversity on team performance. Some have shown that diversity helps performance, while others have found a negative relationship between diversity and performance. When different studies show conflicting results like this, it's usually a sign of a missing moderator. In this case, psychological safety could be that missing ingredient –the factor that could make or break a diverse team's ability to put its different perspectives to good use. Indeed, in one study in a Midwestern mid-size manufacturing company, a positive climate for diversity and psychological safety together led to more discretionary effort. These relationships were stronger for minorities than for whites, suggesting that psychological safety may be playing an especially crucial role for minorities in creating engagement and a feeling of being valued at work.40

Bringing Research to Practice

The research summarized here, which is steadily growing with consistent observations across diverse industry settings, provides further confidence that psychological safety truly offers benefits for organizations and countries around the world. No longer confined to academic interest, psychological safety has garnered attention from practitioners in almost every industry – especially in the aftermath of Google's Project Aristotle, with its feature pieces in the New York Times and on Fareed Zakaria GPS on CNN.41 More and more professionals – consultants, managers, physicians, nurses, engineers – can be found talking about psychological safety. Yet few may be aware of the full weight of supporting evidence that it matters. And fewer still may have stopped to reflect on what their companies lose when psychological safety is missing.

One of the most important things to keep in mind, wherever you work, is that the failure of an employee to speak up in a crucial moment cannot be seen. This is true whether that employee is on the front lines of customer service or sitting next to you in the executive board room. And because not offering an idea is an invisible act, it's hard to engage in real-time course correction. This means that psychologically safe workplaces have a powerful advantage in competitive industries.

The four chapters ahead in Part II vividly portray the consequences of workplace fear (Chapters 3 and 4) and the benefits of psychological safety (Chapters 5 and 6) for both organizational performance and human safety. We'll visit more than 20 organizations – old and new, large and small, private and public sector, domestic and overseas. Examining events that transpired in companies as diverse as Volkswagen and Wells Fargo, I hope to convey a visceral understanding of what is lost in fear-based workplaces, which are, alas, all too often still the default in organizations around the world, even after two decades of research providing evidence of its costs. Taking a look inside a range of fearless organizations, such as Pixar Animation Studios and DaVita Kidney Centers, I also hope to convey all that is gained.