pan shot

In a pan shot, the camera scans space horizontally pivoting left or right while remaining stationary, mounted on a tripod or even handheld. The term pan is short for panoramic: the showing of an unbroken view of an area. Panning shots are often used to follow a subject as it moves across a location (called pan with shots), and are said to be “motivated” camera moves because the movement of the subject motivates the movement of the camera. Pan shots are also used to shift the view from one subject to another; in these shots, also called pan to shots, the movement of the camera is not motivated by the movement of a subject, making the camera move more apparent to the audience unless some aspect in the narrative internally motivates the pan; for instance, a character looking at something off-screen can motivate a pan that reveals what she is looking at when it traces her gaze. Panning the camera instead of using individual shots to cover a particular aspect of a scene should take into account that a pan preserves the integrity of real time and space, and therefore can convey to an audience that some special connection is taking place that requires its use. For instance, you might want to pan with a character as he moves about a location to establish, in real time, how long it takes him to get across it, or the spatial relationships that exist at that location if this information plays a critical role in your story. Panning can also be used to preserve the integrity of a particularly important performance by an actor that could have its impact diminished if editing were used instead. An argument between a couple, for instance, could be covered by panning back and forth between them instead of using a more typical shot/reverse shot combination, to convey the heightening of emotions as they get increasingly agitated; the panning speed of the camera could even be choreographed to match the intensity of their exchange, while letting the audience experience the argument in real time would make the scene stand out from other scenes that use conventional editing techniques. All of these factors can be considered when trying to decide whether to use a pan shot or a combination of shots to cover a particular scene or moment within a scene in your film.

The example on the left, from Akira Kurosawa’s Kagemusha (1980), uses a pan with shot to follow the titular character (Tatsuya Nakadai), a lowly thief, as he impersonates a recently deceased general. As he reviews his troops, he gets caught up in the excitement of suddenly being treated as a respected leader, breaking into a furious gallop while his soldiers cheer him. Kurosawa pans with the character as he makes his way by the troops, using a telephoto lens that narrows the field of view considerably. The resulting shot, a Kurosawa stylistic signature, makes the impersonator look like he is moving much faster than he really is because of the telephoto’s effect on movement across the x axis of the frame while panning, effectively conveying his unbridled exhilaration in this scene.

This pan shot from Akira Kurosawa’s Kagemusha (1980) takes advantage of the reduced field of view of the telephoto lens to accelerate the perceived motion across the x axis of the frame as it pans with the titular character (Tatsuya Nakadai).

pan shot

why it works

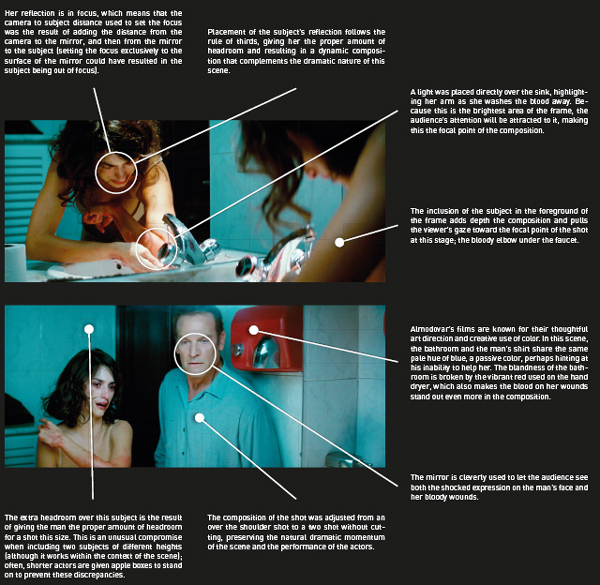

Panning can be used as an alternative to editing when it is preferable to preserve the integrity of a particularly meaningful performance, relationship, or moment in a scene. In this pivotal scene from Pedro Almodovar’s Broken Embraces (2009), Mateo (Lluís Homar) enters a bathroom to discover that Lena (Penélope Cruz), his lover and the star of his film was physically abused by her pathologically jealous married lover, a wealthy businessman. The entire scene plays without any edits, panning from Lena to Mateo when he enters, then back to Lena when he notices her bloody bruises, culminating in a two shot that maximizes the use of a mirror to show both his reaction and her wounds in the same image. The use of handheld panning within a single shot instead of editing shots of various sizes adds tension and realism to their encounter, letting the audience witness the action as it unfolds in real time.

technical considerations

lenses

Since a pan scans space horizontally, your choice of focal length can have a major impact in how the audience perceives movement across the x axis relative to fixed objects in the foreground and background of the frame. For instance, a pan with shot that follows a subject with a wide angle lens will make it look as if he is moving slower across the frame than he is in reality. This effect is the result of the wider field of view that shorter focal length lenses have, and becomes more pronounced with wider angle lenses. If the same shot were taken using a telephoto lens, the effect would be reversed, with the subject appearing to move faster across the x axis of the frame, as seen in the example from Kurosawa’s Kagemusha at the beginning of this chapter. Focal length also has an impact on the speed at which you can safely pan without creating a strobing effect, as explained below.

equipment

The panning of the camera should be absolutely steady unless camera shake is part of the visual strategy you designed for your film (by choosing to shoot with a handheld camera, for instance). Any jerkiness will immediately call attention to itself and make the audience aware of the camera, so if a smooth pan is desired, it is imperative to make sure that the tripod head allows you to have precise control over the speed and movement of the panning action. Most tripods come equipped with some resistance mechanism (friction or fluid based) that smooths out panning and tilting to a constant speed; this resistance is adjustable, so that you can pan as slowly or as quickly as necessary with an even pace throughout. Before panning, it is important to make sure the tripod is perfectly level, otherwise the pan will gradually dip or rise; most tripods have a bubble that lets you level the head on which the camera rests precisely for this purpose. It is also important to be aware of the strobing effect that can appear at certain panning speeds when shooting at 24 or 25 fps (with either film or video); if a pan moves beyond a certain speed, strobing, or a stuttering of the image, will be seen. This effect will become more pronounced with longer focal lengths, and will also be affected by the shutter angle being used. The general rule of thumb to prevent strobing is that it should take about 5-7 seconds to pan across the length of the frame; panning at this speed will ensure that the image will not judder (most cinematography manuals have panning speed tables you can consult for this purpose). There is, however, one type of pan in which strobing is of no concern; a swish pan, where the camera snaps from one subject to another, purposely creating a blurry image while in transit. Swish pans are commonly used as transitions between scenes, using the resulting blur to conceal the edit point between two shots. They are sometimes also used within a scene to quickly pan from one subject to another, placing a dramatic emphasis on the subject at the end of the pan.

lighting

Whether you are panning with a subject or panning from one subject to another, the depth of field you have will affect your ability to maintain focus throughout the shot. If, for aesthetic or technical reasons, you choose to use a shallow depth of field while panning from a subject to another, you might have to adjust the focus if the second subject if placed at a different distance from the camera than the first subject. However, if you wanted to have all subjects in focus as you pan, you would need to have a deep depth of field, which can only be obtained by using a small aperture that requires enough lighting to avoid underexposing your image. This will of course not be a problem while shooting day exteriors, but might prove challenging while shooting indoors or night exteriors.

breaking the rules

A swish pan (a shot that pans the camera fast enough to create blur) is used in this scene from Edgar Wright’s Hot Fuzz (2007) to shift the view to top London Cop Nicholas Angel (Simon Pegg) as he arrives to meet his girlfriend Janine (Cate Blanchett), only to find out she has dumped him. Swish pans are commonly used as transitions between scenes, or to place a dramatic emphasis on a subject at the end of the pan when used within a scene. In this example, however, a swish pan is used to conceal an edit within the same scene, and the dramatic emphasis is used as a visual punch line; Wright’s work is known for appropriating visual techniques from the horror and science fiction genres for his comedies.

Solaris. Steven Soderbergh, 2002.