medium long shot

Medium long shots include a character or characters from approximately the knees up in the frame; they are wider than medium shots, but tighter than long shots. These shots are also sometimes known as “American shots,” originally named by European critics because they were first introduced in early American western films (according to film history lore, this shot size was created to include characters and their gun holsters). Medium long shots are commonly used for group shots, two shots, and emblematic shots, because they provide enough room in the frame to include several characters or visual elements simultaneously. While the long shot emphasizes the body language of a character and the surrounding area, the size of the medium long shot allows you to showcase body language, some facial expression, and the surrounding area simultaneously, making them ideal for situations when a relationship between these three visual elements needs to be established to present a narrative or expository point to the audience. The size of a medium long shot is also ideal to establish the dynamics of a relationship between characters, by the way they are placed within the composition (by using Hitchcock’s rule, or balanced/unbalanced framings, for instance). Like long shots and medium shots, medium long shots are commonly used in combination with tighter shots to control the emotional involvement of the audience (normally by cutting to medium close ups or close ups at key moments of a scene), but because they can pick up some facial expression, medium long shots can also be used by themselves without completely sacrificing the kind of emotional connection that is associated with tighter shots. The relatively wide coverage of medium long shots makes it necessary to keep them on the screen slightly longer than tighter shots with fewer visual elements, especially when they are used at the beginning of a scene to set up the spatial relationships between characters or between characters and their surrounding area.

The medium long shot on the opposite page, from Luc Besson’s Leon: The Professional (1994), features a small exchange between the titular character (Jean Reno), an expert hitman, and Mathilda (Natalie Portman), a 12 year old he saved from a gang of corrupt cops. In the previous scene, Mathilda proved her intent to become a killer by blindly shooting a gun out of his apartment’s window, prompting Leon to move out. The medium long shot that follows is used as a reveal: Leon appears first in the frame as he walks toward us, tricking the audience into thinking he has ditched Mathilda. As the shot continues, Mathilda enters the frame revealing that he has in fact decided to let her tag along. The scene plays out entirely in this shot as they have a brief exchange, relying on the ability of the medium long shot to show some facial expression and much body language. The central placement of the characters in the frame, combined with the exclusion of most of the background and the use of shallow depth of field, isolates them from their surroundings, underlining the awkwardness of their pairing by letting the audience concentrate on their dramatically contrasting costumes and physical appearance.

A medium long shot perfectly showcases the differences in height, physical appearance, and wardrobe between Mathilda (Natalie Portman) and Leon (Jean Reno) in this exchange from Luc Besson’s Leon: The Professional (1993).

medium long shot

why it works

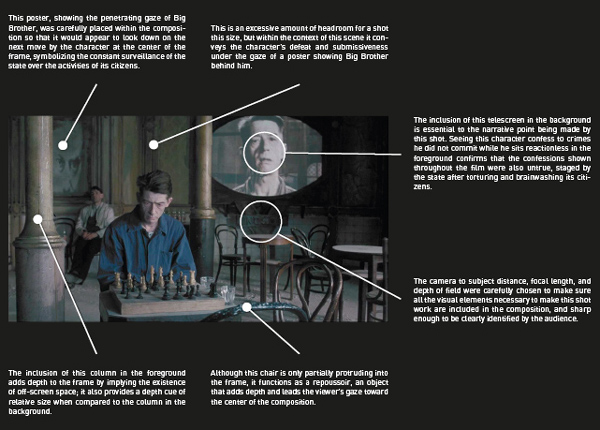

The size of a medium long shot is ideal to showcase a character’s body language, some facial expression, and the surrounding area simultaneously, a characteristic used to maximum effect in this example from the poignant ending of Michael Radford’s adaptation of George Orwell’s dystopian Nineteen Eighty-Four (1984). The composition of this shot is designed to let the audience see Winston Smith (John Hurt), a Party worker at the Ministry of Truth, after he was tortured and brainwashed for committing a thoughtcrime (keeping a diary). He is flanked by a poster with the figurehead of the state, Big Brother, and a telescreen that plays his confession as traitor to the Party. A long shot would not have allowed us to see the listless expression on his face, while a medium shot would have excluded either the poster or the confession, both necessary visual elements to communicate the narrative point of this shot. Note the use of extra headroom over the character, visually emphasizing his defeat by the totalitarian regime that watches over his every move, symbolized by the gaze of Big Brother behind him.

technical considarations

lenses

Because the medium long shot can include a character’s body language and some facial expression along with the surrounding area, the choice of lens can be especially critical, since it can be used to include or exclude visual elements from the frame according to the field of view needed. The example from Leon: The Professional at the beginning of this chapter, for instance, deftly uses a telephoto lens to exclude a lot of the background, directing the audience to concentrate solely on the two characters and their exchange at that time. A very different kind of relationship between character and surrounding area is established in the example from Nineteen Eighty-Four on the previous page, where a lens with a focal length much closer to normal was used, allowing a large portion of the location to be included in the composition (although not as much as would be included if a wide angle lens had been used). In this shot, allowing the audience to see the area surrounding the central character is essential to establish the multiple visual and thematic relationships contained in this complex moment. Focal length can also be selected according to the need for either shallow or deep depth of field in the composition. Actual control over the range of focus will of course be more a function of the aperture and not the focal length, but depending on the distance between foreground and background visual elements, a shallow depth of field will be easier to achieve with a telephoto lens (since it compresses distances along the z axis) than a wide lens (since it expands distances along the z axis).

format

Any type of shot that depends on the manipulation of depth of field to establish a visual relationship between characters or between a character and the surrounding area will benefit from the flexibility of being able to use interchangeable lenses, possible only when shooting film or HD and SD video with the use of a 35mm lens adapter kit. SD cameras and their native zoom lenses make it very difficult to create any composition with a shallow depth of field. Shots that require deep depth of field, however, will not present a problem when shooting with an SD video camera, since the smaller native lenses they use produce inherently deeper depths of field.

lighting

The relatively wide field of view in a medium long shot might necessitate the use of larger lighting instruments when shooting indoors, especially if the composition precludes the placement of lights close to the subject. For instance, in the example from Nineteen Eighty-Four on the previous page, a single light source had to be powerful enough to reach all the way to the back wall. The size of this shot might also prevent you from placing butterflies over the subjects when shooting on sunny day exteriors to control the quality of the light, a very common technique used in medium shots and medium close ups (as seen in the example from Perfume: The Story of a Murderer, in the medium close up chapter). Shooting night exteriors will require powerful lights that will most likely necessitate using a portable generator, or finding a location that has available light that is bright enough to achieve a usable exposure. This problem is exacerbated when shooting SD or HD video since their CCD sensors are less sensitive to light than fast film stocks.

breaking the rules

Medium long shots are generally used to showcase a character and some of the surrounding area, but in this example from Bong Joon-ho’s Memories of Murder (2003), a film based on the true story of South Korea’s first serial murders, a character who fears she is being stalked by a killer is purposely kept out of focus throughout the length of the shot, diverting the audience’s attention to the deserted woods around her instead. This unusual and highly effective technique shifts the focus both figuratively and literally away from the human subject to the deceptively harmless woods before the character is violently attacked by the serial killer. Note that although the character is completely blurred, she was placed in the composition according to the rule of thirds, ensuring a dynamic frame and the proper amount of headroom for a medium long shot.

Sid and Nancy. Alex Cox, 1986.