image system

The term “image system” was originally introduced by film theorists, in articles that tried to create a systematic understanding of film through the analysis of images, editing patterns, shot composition, and ideological tendencies of certain directors. In some film theories, image systems are used to decode the layers of meaning a film might have, based on the connotations certain images have in addition to their literal meaning. For instance, a shot of a character looking at his reflection in a mirror can also signify the concept of a divided self and internal conflict, because of the symbolic meanings associated with mirrors and reflections in psychoanalytic theory; this is a common visual trope found in many films dealing with characters who have personality disorders or are suffering internal conflicts. Image system also has a much simpler definition, most often used by filmmakers and screenwriters; it refers to the use of recurrent images and compositions in a film to add layers of meaning to a narrative. The repetition of images can be a powerful tool to introduce themes, motifs, and symbolic imagery that might or might not be explicitly dealt with within the plot of the film. It can also be used to show character growth, foreshadow important information, and create associative meanings between characters that are not explicit in the story. Because the experience of watching a film relies so much on the use of images (although not exclusively, since the film experience always has involved a sound component, even when films were technically silent), most films have an image system at work at some level, whether the filmmaker intends to have one or not. This visual recalling and comparison is inherent in the way audiences extract meaning from images to understand a story, constantly making connections between and within shots. Image systems can be very subtle, repeating certain shot compositions, colors, and imagery in ways that are not easy to notice at first but are nonetheless internalized by the audience on a subliminal level. In this case, only some viewers might notice the repetition of images and shot compositions and infer their narrative significance, decoding an additional layer of meaning to their understanding of the story. Other viewers, however, might completely miss the connections, accessing only the main narrative of a film. Some filmmakers make the image system in their films overt and impossible to ignore, imbuing numerous shots with iconic, graphic, or symbolic significance, sometimes at the expense of letting the audience connect with the story; this is generally not a good idea, since image systems work best when they support and add meaning to, and not become, the point of your film.

Image systems do not have to rely solely on the repetition of images to make a narrative point. An image system could consist, for example, of shots in which the distance between two key characters is gradually diminished (through actual blocking or by using increasingly longer focal lengths to visually compress the distance between them along the z axis) as their relationship deepens, or shots that gradually switch from high angles to low angles to signal that a character becomes more assertive as the story progresses. An important distinction to keep in mind is that an image system should not be confused with a visual strategy (choices regarding stocks, format, lenses, and lighting). These elements do not constitute an image system, but are instead some of the tools that will make your image system work, in combination with thoughtful shot composition, editing, art direction, and any other element that can be used to develop the explicit and implicit meanings of a shot.

Having an image system is not essential or mandatory; you might not want to deal with having to create one and choose instead to tell your story without any intended extra layers of meaning. On the other hand, coming up with an image system can be a very exciting experience that also helps you get a clearer understanding of your story’s structure (necessary to make the image system consistent and meaningful). To create an image system, you must first identify the core ideas of your story, its main themes and motifs (something you probably did when you devised the initial concept for the visual strategy of your film). Once you know what your story is really about, you can design an image system that supports your core ideas in overt or subtle ways that should be consistently implemented throughout your film. Consistency is essential if you want the image system to be recognized by the audience; it should be used in a systematic way that underlines only those events that are meaningful to the understanding of the concepts and motifs you want to highlight in your story.

image system in Oldboy

Park Chan-wook’s Oldboy (2006) has an intricate image system that uses the repetition of shot compositions and symbolic imagery to add emotional depth to its story of obsession and revenge. Oldboy tells the story of Oh Dae-su (Choi Min-sik), a businessman who gets kidnapped and is then imprisoned for fifteen years; during that time, he learns that his kidnappers have killed his wife and framed him for her murder. Without explanation, Dae-su is suddenly released, befriending a young woman named Mi-do (Kang Hye-jeong) after he passes out at the restaurant where she works. With her help, he finds out his daughter, an infant at the time of his kidnapping, was adopted by a family living in another country. He shortly receives a phone call from the man who imprisoned him, who challenges him to find out the reason behind his kidnapping, giving him a deadline of five days or else he will have Mi-do killed. If he succeeds, the stranger tells him he will kill himself instead. This sets Dae-su on a race against time to save Mi-do and exact revenge on the man who murdered his wife and took fifteen years of his life. With Mi-do by his side, Dae-su succeeds in unraveling the mystery behind his imprisonment; a millionaire by the name of Woo-jin (Yu Ji-tae), who attended the same high school as he, blamed him for the suicide of his sister after Dae-su spread a rumor about their incestuous relationship. Unbeknownst to Dae-su, Woo-jin’s revenge had already taken place by the time he finally confronts him, since he had manipulated everything that happened after his release to make him and Mi-do fall in love. In one of the most shocking film endings of the past few years, Dae-su discovers, to his horror, that Mi-do is in fact the daughter he thought had been adopted fifteen years ago, and that Woo-jin’s revenge was to have him commit incest with her.

The image system in Oldboy is tightly integrated with its narrative; the repetition of compositions and motifs does not work exclusively to add layers of meaning, but is at times an active part of the story, used at key points to advance the plot. For instance, Dae-su discovers that he has had an affair with his daughter through a photo album with pictures of her at different ages that include a photograph he held at the beginning of the film (figure 15), Woo-jin’s sister takes a photograph of herself seconds before she commits suicide, which reappears at the end of the film in Woo-jin’s penthouse. The repetition motif through the mirroring of events and images are also used throughout the story: Dae-su sees his reflection on the photo album when he uncovers Woo-jin’s scheme, Woo-jin’s sister stares at her reflection on a mirror while she has an affair with her brother, a hypnotist makes Dae-su use his reflection on a window to erase the memory of his incestuous affair, and Woo-jin’s revenge scheme is built around making Dae-su fall in love and commit incest with a family member, mirroring events from his life.

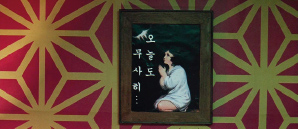

Oldboy also uses repetition in a variety of ways to support the core ideas of the film, amplifying the dramatic impact of the story. Figure 1 shows a painting that Dae-su stares at throughout his imprisonment; it has an inscription that reads “Laugh, and the world laughs with you. Weep, and you weep alone” (a quotation from Solitude, a poem by Ella Wheeler Wilcox). After he is released, he recites this line under his breath a number of times, whenever he finds himself in a dire situation usually set up by Woo-jin. The expression on the face in the painting is ambiguous, making it difficult to tell if its subject (a man with wild hair that resembles Dae-su) is smiling or crying. Figure 2 is from one of the last shots in the film, shown after Dae-su has apparently erased the memory of his incest and reunites with his daughter. Like the man in the painting, it is difficult to tell if Dae-su is smiling or crying, suggesting the horrible possibility that he still remembers the incestuous affair he was tricked into having. His grimace would be heart-wrenching to watch even if the audience did not have the context added by its similarity with the face in the painting and the theme of solitude evoked by the poem, but the visual connection between them and the poem makes this moment in the narrative even more emotionally and psychologically complex.

Figures 3 and 4 show Dae-su in the opening scene of the film, in what we later learn is a flashforward, preventing a man from committing suicide. The striking composition of these shots and the questions they generate (who are these men? Why is he trying to kill that man?) make them easy to recall when they are mirrored at the end of the film, through a flashback (keeping with the theme of reflections and mirrored images) that reveals Woo-jin’s sister committing suicide under strikingly similar circumstances (figures 5 and 6). The repetition of compositions and circumstances shown here suggests a fateful connection exists between Dae-su and Woo-jin, implying perhaps that in their effort to exact revenge on each other, their obsessive behaviors have made them very much alike. This similarity of behavior is made clear several times throughout the film; Woo-jin goes through an unbelievably convoluted scheme to make Dae-su pay for this transgression, waiting fifteen years until Dae-su’s daughter had become a woman to exact his revenge. Dae-su, on the other hand, spends the last ten years of his imprisonment transforming himself into a killing machine, letting go of much of his humanity in the process as he also prepares for revenge. By the time of their final confrontation, their similarity is so pronounced that even the simple act of putting on a shirt is visually connected by the use of almost identical shot compositions and narrative emphasis, with an extreme close up of Dae-su buttoning a cuff (figure 7), that is recreated a few minutes later when Woo-jin is shown doing the same thing (figure 8).

The symbolism associated with certain imagery is also used to establish a connection between characters. Figure 9 shows Dae-su at the beginning of the film, showing off a pair of toy angel wings he bought for his daughter the day of his kidnapping; toward the end of the film, Woo-jin has the wings delivered to Mi-do while Dae-su learns the truth about his relationship with her. She tries the toy wings on and attempts to make them flap, like her father did (figure 10). The repeated action and imagery adds poignancy to the reappearance of the wings (they were finally delivered after fifteen years), while the symbolism associated with angels adds a religious subtext to these scenes; Mi-do and Dae-su have fallen from grace because of the sin they committed and can no longer fly. Religious imagery is also suggested by the reenactment of a painting seen in the prison-room Mi-do stays in while waiting for Dae-su to come back from his confrontation with Woo-jin. A close up of the painting shows a little girl praying (figure 11), a composition that is recreated in a long shot showing Mi-do praying (figure 12). Her connection with the painting in the prison-room also recalls Dae-su’s connection with the painting in his own prison-room while he remained in captivity (figures 1 and 2).

Image repetition is also directly acknowledged in the plot, in a scene where Dae-su, following clues left by Woo-jin, visits one of his old high school classmates at a hair salon. While he gets information from her, a young woman enters the shop; Dae-su, who moments before was shown to be strangely attracted to her classmate’s exposed knees while she was trying to recall a name, turns his attention to the young woman’s knees, shown in a close up (figure 13). Suddenly, the sight of the girl’s knees triggers a memory in Dae-su about an encounter he had in high school with Woo-jin’s sister, introduced in a flashback also with a close up of her knees (figure 14). Dae-su could not remember this encounter until he saw the girl’s knees, suggesting the possibility that he might have blocked this memory of her because of the psychological trauma he associated with this encounter. This point is reinforced when Dae-su is shown going back to the room where he witnessed Woo-jin and his sister having their incestuous affair. It is only when he revisits the actual spot where he spied on them that he is able to remember the event and finally reveal the reason for Woo-jin’s revenge.

The image system in Oldboy also uses repetition to show character growth and change. Figure 15 shows Dae-su at the beginning of the film, holding a picture of his family while drunk at a police station; during his final confrontation with Woo-jin, that composition is repeated when he shows him the picture his sister took seconds before her suicide (figure 16). This time, however, Dae-su looks focused, determined, and threatening. He has essentially become a new man, transformed by his ordeal, a change that is also reflected by the blood red shirt he wears here instead of the white shirt he wore at the police station. These two shots also summarize Dae-su’s arc in the story: he goes from living an inconsequential and carefree life to living a life filled with purpose (revenge), from taking his family for granted (he gets drunk and arrested on his daughter’s birthday) to making them the focus of his life (he plans to avenge his wife’s murder and eventually reunite with his daughter), from being an out of shape businessman to becoming a one-man killing machine.

A more typical use of an image system includes the repetition of a particularly easy to remember image toward the end of a film, signaling to the audience that the story has come full circle and is therefore about to end. Figure 17 shows Dae-su being released from his imprisonment early in the film after a hypnosis session, while figure 18 shows him in the last scene in the film, after he wakes from another hypnosis session designed to make him forget the incestuous affair he had with his daughter. The composition of both of these shots is purposely unusual and therefore easy to recall by the audience, with both shots employing a high-angle long shot that shows Dae-su staggering on the ground. This particular use of an image system is very popular among filmmakers, even in films that do not incorporate image systems as intricately as Oldboy does. One reason is that repeating images in this way does more than bringing the story full circle; it also gives the audience the impression of narrative closure with no unresolved questions, even if this is not truly the case.

Oldboy has a complex image system expertly interwoven with its narrative, used in a way that amplifies and adds dramatic resonance to the themes and motifs that are already present in its story. This is by far the best way to use an image system, to deepen the emotional impact and audience engagement with a filmic narrative, adding layers of meaning that reward an attentive audience and invite repeated viewings of a film, as new depths, dimensions, and understandings can be gleaned every time the story is revisited. However, the implementation and effectiveness of an image system also relies on the creation of meaningful, narratively compelling compositions for every basic shot of the cinematic vocabulary, the topic of the rest of the chapters in this book.

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

Sex and Lucia. Julio Medem, 2001.