extreme close up

The extreme close up allows you to concentrate the audience’s attention on a tiny detail of a character or on small objects. While the close up lets the audience see nuances of a performance that would normally be lost in wider shots, the extreme close up can effectively isolate even smaller, single visual details from the rest of the scene. If the detail is extremely small, sometimes these shots are obtained with the use of specialized lenses, and are called macro shots, but narratively, they still function as extreme close ups. Using an extreme close up to frame a small object or a detail of a character instantly generates the expectation that what is being shown is important and meaningful to the narrative in some way (an application of Hitchcock’s rule). Extreme close ups can also be used to make very powerful visual statements within the image system of your story. A common use of the extreme close up involves the isolating of an object or a detail of a character that is seemingly unimportant, but ends up playing a critical role later in the narrative. In this case, the extreme close up visually underlines the importance of the object so that its reappearance will not seem unjustified and artificially convenient, and to elicit the audience to anticipate a possible connection as the narrative unfolds. In some cases, the extreme close up works as an abstract shot, letting the audience focus on visual details that might not be directly related to the narrative, but nonetheless add to the overall dramatic tone or thematic content because of the abstract or symbolic qualities associated with the image. A good example of this occurs during the opening of David Lynch’s Blue Velvet (1986), where after a series of shots that include idyllic images of small-town America, the montage ends with an extreme close up of black beetles crawling under a perfectly manicured lawn; the beetles are ultimately irrelevant to the plot, but their appearance within the context of the sequence suggests the thematic idea that primal violence can lurk beneath a surface of idealized social order.

In the example on the opposite page, from Julio Medem’s Sex and Lucia (2001), an extreme close up is used to concentrate the audience’s attention on the path of a single tear as it rolls down the cheek of Elena (Najwa Nimri), a woman who had a torrid affair with a man she met while on a secluded Mediterranean island. The scene opens with a graphic match dissolve from a full moon to a circular pregnancy test with a “plus” sign. Upon seeing it, she sheds a tear that falls on the test, partially smearing the positive result. The visual emphasis the extreme close up places on the tear (because of the closeness of the shot, and by using camera movement to follow its path) imbues this detail with symbolic and even poetic meaning, because of the associations it can elicit (salt water, the sea, tides, moon cycles, menstrual cycles, pregnancy, etc.). In this case, the extreme close up was used to make a thematic point that could only be made with this type of shot.

This arresting extreme close up from Julio Medem’s Sex and Lucia (2001) follows the path of a single tear as it runs down the cheek of Elena (Najwa Nimri), a woman who just found out she is pregnant. The tear, a reminder of the seawater in which her fateful sexual encounter took place, will eventually fall on a pregnancy test.

extreme close up

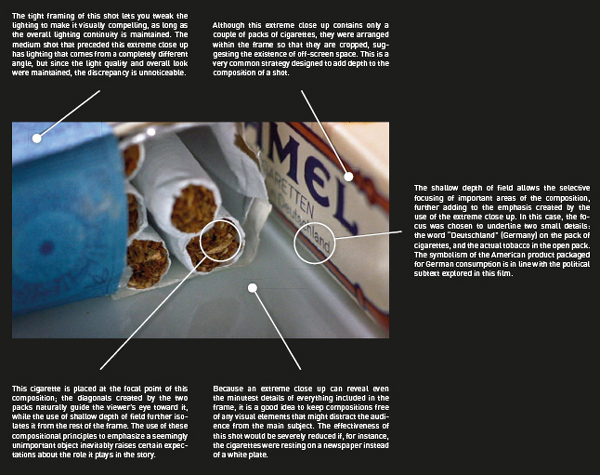

why it works

One of the uses of the extreme close up is to make a strong visual statement by concentrating the audience’s attention on a small detail of a subject. This usually generates the expectation that this detail will have an important role to play in the larger canvas of the story, even if it is unclear what that will be when the shot is first presented. In this example from Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s The Marriage of Maria Braun (1979), an extreme close up shows a pack of cigarettes early in the film, after it is established that they are used as currency in Germany after WWII. At this time in the story it is not clear why this shot (and the narrative emphasis it provides) is being used. At the end of the film, when the title character meets her demise because of a pack of cigarettes, we understand that this extreme close up was actually foreshadowing their importance in the story, adding an element of inevitability to her life, while commenting on the political history of Germany since World War II.

technical considerations

lenses

Depending on the size of the subject being shot, long focal length lenses or wide angles are more commonly used. Both lenses can produce shallower depths of field (the telephoto because of the optical characteristics inherent to this kind of lens, and the wide angle because of the extremely short distance it will require between the camera and the subject to create a tight framing). Zoom lenses are at a disadvantage if they are used as wide angles, since a prime wide angle with the same focal length as a zoom at that setting will be able to focus at a much closer distance, capturing smaller details of the subject in the frame. The native zoom lenses on many SD and HD cameras also make it relatively easy to shoot extreme close ups, because their shorter focal lengths (the result of the smaller-sized CCD sensors they use) allow very short minimum focusing distances. In some cases, the subject might be too small to capture with standard lenses regardless of the format, requiring the use of specialized lenses that allow you to focus even closer than a prime lens. Shots that use these lenses are referred to as macro shots, because they normally use a macro lens to capture the image (although there are other ways to get the same results; please check out the macro shot chapter for more information).

format

The closeness of this shot sometimes makes it difficult to see all the detail that will be captured, especially when using a wide angle lens that will probably be very close to the subject. In these cases, the use of a large preview monitor can be extremely helpful to see and fully exploit the textures and visual details that an extreme close up will reveal when projected. Shooting film will make using a preview monitor impossible unless you have a film camera equipped with a video assist system that will let you see what the lens is seeing. SD and prosumer HD cameras have a slight advantage over film cameras in this regard, since they allow you to preview exactly what the resulting image will look like if you use a preview monitor that approximates or matches the resolution of your shooting format. It is best to avoid using the LCD displays that come with most cameras, since they are far too small and lack the resolution and contrast to display every detail being captured. The same cannot be said for film cameras, since even if you were to use an HD-capable monitor to preview the feed sent from a video tap, it would not be capable of displaying the full resolution of negative film stock.

lighting

Whether the subject is a person or an object, lighting should be planned and executed as carefully as if you were shooting a key close up of one of your leading characters. It is easy to forget that although you might be shooting something that is very small, the size of this shot will make a strong visual statement, making it critical that the lighting supports the narrative point being made. The tightness of the framing will most likely preclude the inclusion of light sources that were established in wider shots, giving you license to add, move, and change their direction to produce a shot that is visually compelling, provided that overall lighting continuity is maintained (meaning that you should not suddenly light an extreme close up using a low-key, film noirish look if the wide shot had high-key, soap opera-like lighting, and vice versa). The example from Clockers on the opposite page takes full advantage of this freedom to tweak the lighting; although in the preceding wide shots the surrounding area of the interrogation room was clearly visible, in this extreme close up the lighting was adjusted so that only the interrogator’s reflection can be seen on the eye, resulting in a visually striking image.

breaking the rules

The tight angles in an extreme close up only allow you to show a tiny detail of your subject, but in this shot from Spike Lee’s Clockers (1995), the reflective qualities of the human eye are cleverly exploited to include much more. When detective Rocco (Harvey Keitel) interrogates Victor (Isaiah Washington) about the inaccuracies of a murder he has confessed to, he tells him: “I want to see what you see” as this extreme close up is shown. The dramatic lighting in this visually compelling shot was carefully planned so that the detective’s reflection would be easy to notice on the pupil of the subject. Interestingly, the word “pupil” comes from “pupilla,” the Latin for “little doll,” an ancient reference to the very phenomenon captured in this shot.

WALL·E. Andrew Stanton, 2008.