emblematic shot

Emblematic shots have the power to communicate abstract, complex, and associative ideas with compositions that reveal special connections between visual elements in the frame. Emblematic shots can “tell a story” with a single image, conveying ideas that are generally greater than the sum of their parts. Audiences watching Luke Skywalker looking at the twin suns of Tatooine in George Lucas’ Star Wars (1977), get more out of that shot than the literal content of the image (young man watches suns setting). Instead, the audience is encouraged to identify larger meanings from the connections and associations contained in the visual elements, specifically by their placement in the composition and the symbolism associated with certain images. These connections transform the concrete meaning “young man watches suns setting” into the symbolic “he feels his future is out of reach” in the minds of the audience. There are many different approaches to create these shots, but the first step is to have a clear understanding of the themes, subtexts, and core ideas in your story; once these are identified, you can design compositions that support them visually. You could, for instance, use Hitchcock’s rule to create a composition that emphasizes a particular visual element over another, or use any of the compositional principles (like balanced/unbalanced framings, the rule of thirds, etc.) to establish a specific relationship between visual elements in the minds of the audience. Emblematic shots are usually placed at the beginning or at the end of particularly meaningful scenes or sequences. When used at the beginning of a scene, they tend to set up the tone of what follows. When they appear at the end of a scene or sequence, they tend to comment on, or contextualize, the events that led to the emblematic shot. Another common practice is to reuse or recreate an emblematic shot toward the end of a film, alerting the audience that a story has come full circle and that the ending is near (a popular technique in image systems). When creating an emblematic shot, think about the meaning being implied by the arrangement of subjects in the shot. Is your composition supporting what is taking place in the scene/sequence/film? Challenging it? Foreshadowing an event that will take place later? Commenting on issues that are not directly related to the plot but are ultimately what your film is really about? Can you take your emblematic shot out of the film, show it to someone who doesn’t know the story, and have him or her recognize what your film is about?

Hal Ashby’s Being There (1979) uses an emblematic shot early in the film, right after its protagonist, an idiot savant named Chance (Peter Sellers), finds himself homeless in Washington, D.C. after the death of his employer. The composition of the shot cleverly suggests Chance’s eventual ascendancy to the presidency of the United States (symbolically represented by the Capitol building and the green traffic light giving him the “go ahead”), while the isolated path he walks on is suggestive of his unique look at life. This simple, yet effective emblematic shot introduces and foreshadows themes that are explored throughout the film.

In Hal Ashby’s Being There (1979), Chance the Gardener (Peter Sellers) finds himself homeless and roaming the streets after his benefactor suddenly dies; the inspired composition of this early shot in the film cleverly foreshadows his ultimate destination: the Presidency of the United States of America.

emblematic shot

why it works

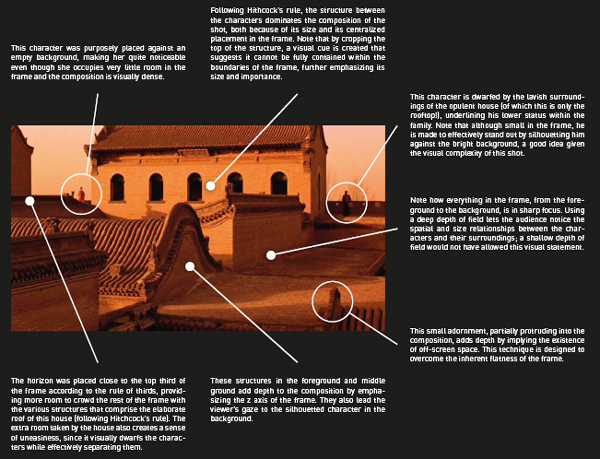

Emblematic shots are not easy to conceive, but they can be very effective at communicating complex, non-verbal, or associative information. In these shots, the director’s take on the themes explored in the film are visualized, through the thoughtful arrangement of visual elements within the frame. A common approach to the composition of these shots is to use Hitchcock’s rule, organizing the visual elements in a way that lets audiences create meaningful connections to the story. In this emblematic shot from Zhang Yimou’s Raise the Red Lantern (1991), Songliang (Gong Li), a girl married against her will to a rich man who already has several wives, has a chance encounter with one of her stepsons, Feipu (Chu Xiao). Although they meet only briefly, this is the first time she has a meaningful emotional connection with a man since her arranged marriage, because traditional “house rules” severely restrict her every move. Appropriately, their last gaze of each other is visually obstructed by a section of her husband’s house, framed to present a formidable obstacle between them, both physical and symbolic.

technical considerations

lenses

Since the emblematic shot relies on viewers making connections between visual elements in the frame, the use of smaller apertures to obtain deep depth of fields (to ensure everything is in focus) is common. While using smaller apertures is not difficult when shooting outdoors on a sunny day (where you will have more light than you need), you will have to have plenty of lights when shooting indoors. If you’re shooting film, there are ways to make it easier to achieve a deep depth of field indoors, by choosing the right film stock (see below). Another technique to get a deep depth of field is to choose a lens with a short focal length, which will produce the appearance of one, but you will have to take into account the distortion it creates and the radical change in the field of view your composition will have. Another option would be to use a specialized lens like a split field diopter, which lets you have both background and foreground subjects in focus simultaneously, with the caveat you will also have an area of blurriness in the middle of the composition (where the join between the two lenses is located). You could also use a tilt-shift lens, which allows you to have a plane of focus along a diagonal toward the z axis, but this will require the careful arrangement of visual elements only along this axis, severely restricting your compositional choices.

format

The smaller apertures needed to get a deep depth of field let less light through, necessitating the use of extra lighting to compensate when shooting indoors. Choosing a fast film stock in this situation will make it possible to use a smaller aperture, since they require less light to record an image than slower stocks. You could also try to increase the camera to subject distance to create a deeper depth of field, but this is not always an option when shooting indoors because of space restrictions. Shooting on SD or HD works in your favor in this case; the smaller CCD sensors most consumer and prosumer cameras use make it very easy to achieve a deep depth of field, since their lenses have to produce a much smaller image and therefore have much shorter focal lengths than their larger format counterparts.

lighting

One of the ways that emblematic shots are identified as such, is through a lighting scheme that is slightly different from the rest of the film, creating a greater impact and demanding extra attention form the viewer. The first two examples used in this chapter exemplify this special attention to lighting. In the example on the previous page, the natural light used in the scene produces very long shadows. The director shot this scene either very early in the morning or very late in the afternoon, obtaining a beautiful orange glow. Shooting during or close to magic hour can produce amazing results, but dramatically reduces the amount of time you have to shoot. Faster film stocks will make it possible for you to continue shooting right up until the sun sets if shooting at dusk, long after digital video cameras start to display video noise. The wide field of view of this shot would have made it nearly impossible to light with artificial lighting, unless cost was of no concern. Just remember that magic hour is never really an hour (but more like 20 to 30 minutes)!

breaking the rules

Although emblematic shots commonly rely on a complex arrangement of visual elements to make their point, sometimes simple compositions, coupled with clever blocking of actors and inspired casting and art direction decisions, can be just as effective. In this medium long shot from Jonathan Demme’s The Silence of the Lambs (1991), Clarice Starling (Jodie Foster) enters an elevator filled with male FBI recruits, who provide a strong visual contrast because of their gender, the color of their uniforms, height, and body language. Clarice is the focal point of the composition, placed at the center of the frame, looking besieged by the males around her (especially by the two at her sides, who seem particularly annoyed by her presence). Her gaze is fixed upward (Lecter tells her that what she seeks most of all is “advancement”) while her hands are clasped over her genitals, one of many visual cues in this film that underline the subtext of sexual tension between Clarice and male figures of authority.

The Soloist. Joe Wright, 2009.