sequence shot

Sequence shots are among the most complex, difficult, and ultimately rewarding shots you can attempt. The term comes originally from the literal translation of the French “plan-séquence,” and refers to a shot that incorporates a sophisticated set of dynamic camera moves and framing over a long take, very often encompassing action from several scenes that would otherwise be covered with a number of separate shots. Sequence shots make an unmistakably powerful narrative statement about the importance of the action they cover and the spatial and temporal relationships between elements in the shot, and therefore they are often used to showcase a crucial set of events that are pivotal to the understanding of the rest of the film. Sequence shots can include crane shots, dolly shots, zoom shots, handheld shots, panning, tilting, tracking shots, and Steadicam shots, often combined seamlessly to create a dynamic frame that can go anywhere from an extreme close up to an extreme long shot. Camera movement in sequence shots is often motivated by the movement of characters, although unmotivated camera movement is also used, exclusively or in combination with motivated movement. Since sequence shots always use long takes (shots that can last anywhere from a minute to well over an hour, depending on the shooting format), they preserve real time, space, and the performance of actors, and can add realism, tension, and dramatic emphasis to a scene. However, this real time aspect does not automatically connote realism, as these shots are frequently stylistically virtuosic and very apparent to audiences. Because of the complexity of sequence shots, filmmakers have found ways to cheat, creating what appear to be extended sequence shots that are in fact a number of separate, mini-sequence shots with their edits concealed. This is often accomplished by cutting between two shots while the frame is completely filled with a nondescript image, like an blank wall or the shadow of a character as she passes in front of the camera, a technique used most famously in Alfred Hitchcock’s film Rope (1948). More recently, the advent of computer generated imagery, or CGI, has made it possible to conceal edits more effectively, making them virtually impossible to detect.

One of the most famous examples of a sequence shot happens during the opening scene in Orson Welles’ Touch of Evil (1958). The shot begins with a close up of a homemade explosive, which is placed in the trunk of a car that later gets driven by a couple on their way to the United States-Mexico border. Their car crosses paths with a newlywed couple (Charlton Heston and Janet Leigh) also on their way to the border, whose romantic interlude is interrupted by the explosion of the car. This entire set of events is astoundingly and flawlessly covered with a single three-minute sequence shot (accomplished with the use of a camera mounted on a crane in the back of a truck) that lets the action unfold in real time, amplifying the suspense and tension set up at the beginning of the shot when the explosive’s timer was set. The intricate camera movement also introduces the border area in a way that is suggestive of the tangled moral, ethical, legal, and cultural clashes that will occur there afterward, one of the key themes explored in this film.

This legendary sequence shot from the opening scene of Orson Welles’ Touch of Evil (1958) allows the action to unfold in real time, gradually intensifying the suspense and tension initially introduced when an explosive device on a timer is shown being triggered at the beginning of the shot.

sequence shot

why it works

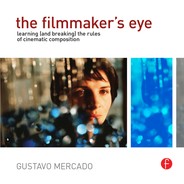

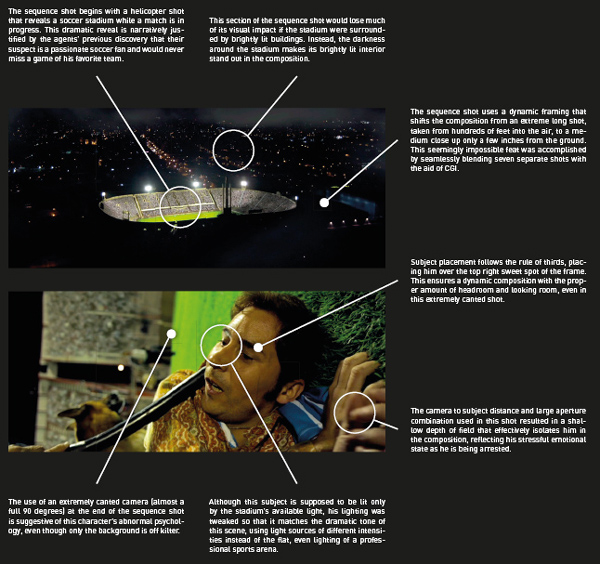

Sequence shots can make a powerful narrative statement that showcases a pivotal and extended set of events, preserving the integrity of time, space, and performance in the process. This crucial scene from Juan José Campanella’s The Secret in Their Eyes (2009) does just that, in an amazing sequence shot (actually seven shots seamlessly merged with the aid of CGI) that begins high above a soccer stadium, glides above the crowds and follows federal justice agents Benjamin and Pablo (Ricardo Darín and Guillermo Francella) as they chase after a murder suspect (Javier Godino, pictured) through the bowels of the stadium, ending with his arrest on the playing field. The extreme dramatic emphasis conveyed by the sequence shot underlines the importance his capture represents and all but confirms his guilt.

technical considerations

lenses

The complexity of the sequence shot will dictate the appropriate focal length(s) or even the kind of lens that will work best for the job. Some factors to consider are: the variety of shot sizes you will be attempting, the field of view necessary at every stage of the shot, the type of camera or subject movement that needs to be emphasized or understated, the minimum camera to subject distance the shot requires, whether a zoom lens will be needed to expand the dynamic frame choices, the need to have a specific maximum aperture, and many other variables. In Welles’ Touch of Evil, the use of a relatively wide angle lens elongated distances and exaggerated movement along the z axis of the frame, added some optical distortion to the architecture of the border town, and produced a wide field of view that allowed the inclusion of much of the richly detailed mise en scène. These qualities reflect the importance the border town plays in the story and present it as a labyrinthine, sleazy, and sinister place, filled with moral and ethical ambiguities. While this example represents a perfect incorporation of visual style and theme, the technical requirements of a sequence shot will sometimes override your desire to use a particular focal length. The same sequence shot, for instance, would have been nearly impossible to shoot with a telephoto lens and a shallow depth of field.

equipment

Sequence shots can require virtually any kind of equipment designed to create a free-flowing dynamic camera move, including cranes, jibs, dollies, vehicles, helicopters, Steadicam rigs, and even a handheld camera. While all dynamic camera moves require extra time to light and to coordinate equipment, crew, resources, and cast, the unique technical requirements of a sequence shot simply cannot be overstated. In fact, it is entirely possible for a sequence shot to take up an entire day of shooting or more, depending on the level of complexity it entails; for instance, it took Michelangelo Antonioni 11 days to shoot a 7-minute sequence shot for his film The Passenger (1975).

lighting

The strategies for lighting a sequence shot are not too dissimilar from the ones used for Steadicam shots and other dynamic camera moves that cover a single wide area or numerous distinct spaces. If shooting night interiors, the use of practicals (sources of light visible within the frame that are part of the mise en scène) can be extremely helpful, since a roaming camera is likely to prevent you from placing movie lights where you normally would. In some cases, a crew member is enlisted to travel alongside the camera with a portable light source to provide sufficient and constant exposure to a moving subject, although this raises the level of complexity of an already technically demanding shot. Day interiors can be lit using only motivated light coming through windows, allowing the camera to travel freely without worrying about the placement of lights within the location. Night exteriors, as always, present a formidable challenge unless you have access to large lighting fixtures that can be raised high enough to pass for moonlight, even though it would never be that bright in real life. Another option would be finding a location with enough available light so that very few additional lights, if any, would be needed (as seen in the sequence shot example from Campanella’s The Secret in Their Eyes). More often than not, it will be extremely hard or even impossible to have perfect lighting throughout an entire sequence shot, so you should decide beforehand what the key moments are so that you can choreograph and light them accordingly.

breaking the rules

It is impossible to overstate the spectacular achievement accomplished in Aleksandr Sokurov’s Russian Ark (2006), a film that uses a single, 91-minute Steadicam sequence shot to transport the audience through 300 years of Russian history as they explore the Hermitage Museum. This shot incorporates virtually every type of shot described in this book, and it was made possible thanks to the use of a Steadicam and a portable hard drive recording system.