The Four Seasons of Ethnography

A Creation-Centered Ontology for Ethnography

In this chapter, similar to Aluli-Meyer’s endeavor to introduce an alternative epistemology for knowledge production (Chapter 9), Sarah Amira de la Garza proposes a non-Eurocentric method of ethnography called “The Four Seasons of Ethnography,” which is predicated on the creation-centered ontology of organic and circular order as opposed to the “naturalistic” paradigm grounded in the Western linear, mechanistic, and positivistic worldview. She critically reflects on the four guiding ideals of Western “naturalistic” ethnography: (1) opportunism with linear and material orientations to time and process; (2) the assumption of independence of researcher that prescribes a separation of the researcher and the researched; (3) the entitlement of the researcher with a dominating relationship with cultures studied and nature; and (4) primacy of rationality that silences spirituality, emotionality, and other forms of interpretive voices. Using the metaphor of four seasons to describe the entire process of ethnographic research rooted in the creation-centered circular cosmology, De la Garza then ventures to formulate the guiding ideals of the Four Seasons of Ethnography: (1) natural cycles (appropriateness) of the processes and experiences of living beings, (2) an awareness of interdependence of all things, (3) preparedness, and (4) harmony/balance (discipline).

Background

My first professional encounters with the study of culture came under the tutelage of Asante (1987, 1988, 1990) to whom I was assigned as research assistant at the State University of New York at Buffalo in 1980. He taught me much about the interaction between ontology and notions of race and ethnic identity by exposing me to his work on Afrocentricity and sensitizing me to the ways ethnicity and race manifested in organizational and academic politics. I was then a student of organizational and interpersonal communication. Dr. Asante has remained my friend and mentor over the last two decades, and his influence has been tremendous. During that time, I was encouraged to study ethnography from anthropologist Fred Gearing, known for his work among Native Americans. I was also taught statistics, methods of network analysis, conversation analysis, organizational auditing, and interactive computerized surveys. This multi-methodological approach would continue to characterize my experience as a doctoral student at the University of Texas at Austin, where I studied sociolinguistics with the British linguist Bickerton (1992, 1996), conversation analysis with the late Hopper (1992), variable analytic research with Ed Hayes and with John Daly (see Daly et al., 1997, 1998), rhetorical analysis with Hart (1987, 1996) and grounded theory and ethnography with Browning (see Browning & Shetler, 2000) and the sociologist Snow (1993).

While a Fulbright professor in the city of Chihuahua, Mexico during 1988–1989, I was sent to the faculty of psychology at the Universidad Autónoma de Chihuahua to teach qualitative research methods. This was the first year of the administration of President Salinas de Gortari, and a massive effort to “modernize” Mexico was underway, with government expectations of unquestioned solidarity. During that year, I conducted a study of the identity of Chihuahuans during this process of modernization. Based on my daily observations that many Mexicans seemed to pride themselves on both their modernity and their traditionalism, I wanted to see what they would choose if faced with questions designed to identify their preference. The study was multi-methodological and conducted in various phases, including interviews, focus groups, and factor analysis of survey items generated to reflect an array of views held to be either modern or traditional according to the work of Inkeles and Smith (1974). What I found was that Mexicans in Chihuahua could not be identified as “either/or,” but both modern and traditional. The resulting paper which I presented at a 1991 border studies conference in Mexico (González & Cole, 1991) questioned the cultural assumptions of factor analytic methodologies and their appropriateness for use in cultures that do not value exclusive binary categorization of experience. If contradiction is not culturally problematic, then consistency in response cannot be taken to be an indication of validity. Reliability becomes practically moot as an issue.

It was largely in this sort of intellectual environment that I was led to question how it is that persons come to believe they understand a culture in the first place. I could see what I believed to be a tremendous interplay between the methodologies accepted for the study of culture and the cultures themselves that produced those methodologies.

Upon my return from Mexico, I spent the time from December of 1989 to July 1992, preparing for, engaging in, and writing an ethnographic exploration of the sharing of Native American (chiefly Lakota) spirituality between “Indians and non-Indians” (see González, 1998). During that time, I watched the constant construction and deconstruction of individuals’ ethnic identities as such related to the rights of access, ownership, practice, and dissemination of spiritual traditions and practices. Additionally, I witnessed debates on the rights of individuals to define themselves ethnically. The individuals I confronted and grew to know well during this study were marginal in many ways. The “White” non-Indians identifying with Native American cultural traditions, changing their names, abandoning their families and disassociating from their own cultural histories, were “choosing” this identity as a voice against the “meanings” of being non-Indian. It was a way to disassociate one’s self from the history of one’s cultural group and to identify with an idealized other. In a fascinating way, the re-identification that took place allowed for high levels of self-deprecation and rejection of one’s family and history as a perceived way to increase the “correctness” or “worth” of the self. The Native Americans sharing and teaching spiritual practices also were creating and maintaining an identity that had privileges of sovereignty and ownership of their traditional ways. This manipulation of ethnicities drew my attention because of the implicit awareness of the significance of identification, in many instances seemingly related to a desire to disassociate from cultural, familial, national, or personal histories of oppression, abuse, failure, waste, and other manifestations of domination. I realized that in many ways, this dynamic seemed present in the methodological trends in our field.

The Four Seasons of Ethnography are introduced as a methodology for ethnography that stemmed from my awareness that the dynamics we find in often problematic intercultural contexts are often pervasive in studies of culture. I considered the reality that the taken-for-granted approaches to reasoning and rhetoric which we put forth as academic discourse were themselves exemplars of a greater cultural ontology that assumes hierarchical relations of domination. How could I proceed to seek insight into the questions that motivated me without further reifying those structures? In 1987, Molefi Asante suggested a different, Afrocentric, ontology for rhetoric, and demonstrated its implications. Asante’s approach to reconceptualizing taken-for-granted ontologically rooted structures motivated me. I asked myself, what would the ethnographic study of others look like if it were done from a perspective that at this point in our history is not taken-for-granted?

This is the question that motivated me in 1991 to begin formulating a methodological approach to ethnography that grew out of a cultural ontology of organic, circular order, one that I call creation-centered (Fox, 1991, 1994, 1996), significantly different from a received Western, linear, mechanistic and positivistic worldview. I was frustrated by the outcomes of works inspired by Lincoln and Guba’s (1985) hallmark work on the “naturalistic” paradigm. The enthusiastic “new” research which graduate students and others developed often seemed to me to simply “dress up” otherwise still Western, linear understanding. I struggled with the growing awareness that my own indigenous1 cultural ontological position was informing a different reading of Lincoln and Guba. The Four Seasons of Ethnography evolved from my gradual realization that the same methods can be used within different methodologies, reflecting the source ontologies which themselves reflect cultural location and taken-for-granted assumptions. I was inspired by the joint works of scientists and theologians Capra and Steindl-Rast (1992) and Swimme and Berry (1992). They were able to critique the mechanistic worldview without rejecting its contributions. The objective and subjective were part of the same experience, not in different boxes. I wanted to do the same. The problems I saw with our received view were not because it was “evil,” but because when treated as if it is a separate view, its implications are problematic. I searched non-traditional sources for insight, including my own cultural positioning as a woman scholar of Mexican mestizo ancestry.

Birth of the Four Seasons as Ontology for Ethnography

Capra and Steindl-Rast (1992) discuss paradigmatic conflicts in the natural sciences. In their dialogue, Capra claims that the traditional scientific paradigm does not allow for any work conducted from other paradigmatic perspectives to even be called “science.” However, they assert, this does not mean that science is not possible from other perspectives. Systematic observation and development of theory are the necessary components for the development of a science. The oral traditions of the creation-centered non-materialist and organic cultures of the world are replete with assertions of “learning by watching.” The cycles of nature become the experiential source of a circular cultural ontology. The scientific knowledge of people not governed exclusively by positivist rules for knowing is oftentimes disregarded due to the implicit and tacit forms of their accustomed methodologies. In order for science conducted within these paradigms distinct to the traditional Western academic “received” view to be understood, the ways of those alternatives must be articulated.

Capra and Stcindl-Rast explain that social communities, and indeed cultures, are themselves paradigmatic and therefore offer alternatives to the traditional ways to do science. However, the European/American models for science, based on domination and control, they say, have become so prevalent, that even in nations whose everyday cultures are quite distinct, scientific work tends to reflect the traditional “Western” paradigm. When the methodology is driven by the paradigmatic source, the work will always reflect that paradigm, regardless of the culture or personal/political leanings and preferences of the researchers.

The Four Seasons is my attempt to reformulate the task of ethnography, as it might be viewed through the methodology of a circular ontology as experienced and often expressed by Native American “Indian”2 cultures. My own experience as a child was heavily influenced by the lessons taught to me by my Mexican Indian-Spanish grandparents. The “folk” theories of my grandfather Manuel (of Comanche and Rarámuri Mexican ancestry) were all based on his systematic observation of human behavior and nature. His life as a social and political activist was rooted in these tacit theories and aided by his spiritual practice of praying to the Mother at sunrise, noon, and sunset each day. My grandmother Fina (of Lipán Apache Mexican ancestry) was a champion unobtrusive observer, sitting dutifully by her window each day watching the community come and go in the Mexican barrio where I lived as a child. We called her juzgona,3 teasingly referring to her opinions freely given based on those observations. She had a daily spiritual practice and was a weather-watcher, often walking many miles in a day to gather and deliver the herbs that were needed by someone in the community.

My grandfather Cosme of Basque and Sephardic Spanish ancestry was a silent, meditative man who read rigorously and compared the newspaper reports daily, able to provide situated opinions on the circumstances that surrounded him. Orphaned after his father was murdered by a conspiratorial group of Texans seeking to gain access to lands owned by Mexicans, he spent time during his childhood as a servant to an Anglo-Texan family and watched his last name changed from the Basque Urueta to Ureta, which was easier for Anglos to pronounce. Developing alcoholism in his adult years, he taught me of the pain existing in the spaces “between,” not too different from the pain of having to present our cultural realities through only one set of lenses (see González, 1995).

Mama Carmelita, my paternal grandmother, kept daily journals for over 50 years, and she wrote in them faithfully each night, recording the events of the day and her observations of those events. She shared her reflections on the present by comparing it to her experience growing into womanhood—the daughter of a soldier in the Mexican Revolution, and fleeing to the USA from the religious oppression of post-revolutionary Mexico. From her I learned of the pain of hegemony and of the complexity of a life story, as well as the strength that can be maintained through dutiful practice of recording one’s accounts.

These were my models for my ethnographic practice and research identity, long before I used such terms. They provided the cultural ontology that served as the backdrop for my practice of ethnographic methods I would one day learn. From them all, I learned a methodology that was rooted in a spirituality of the seasons of life, action gauged in response to one’s environment. It is from this ontology, garnered through the lived experience of indigenous culture and years of committed study and practice of the metaphysical spiritual traditions of my Native American ancestors, that the Four Seasons were born.

Ontology and Methodology

If rooted firmly in the taken-for-granted assumptions of an ontological position, the methodology for the application of particular methods will reflect the ontology in the ways the methods are developed, utilized and interpreted. The results of one’s research cannot be assumed to reflect a particular ontological position, simply because of the prototypic appearance of the methods. Research by many in the social sciences has moved increasingly toward a validation of a relativist ontology, often in the guise of postmodernism, at other times simply reflecting the politics of positionality. This has been reflected in the utilization of qualitative, narrative, situational, and autobiographical methodologies for data collection, analysis, and writing (Denzin, 1997; Ellis & Bochner, 1996; Goodall, 1989, 1991, 1996, 2000; Banks & Banks, 1998).

It has been my experience in the pedagogy of qualitative research methods that recent converts and zealous students new to the freedom of applied relativism will often be drawn by the aesthetics and/or emotional appeal of the subjective methodologies, not fully understanding the ontological approach that supports them. An ontology involves far more than a difference of opinion; it is the basic structuring set of assumptions of what can be taken as real. It follows that then an absence of ontological awareness, comprehension, or commitment can appear in taken-for-granted claims of ontological validity which are assumed simply on the evidence of the subjective methodologies used. The resultant problems in definition and accountability can result in seriously naïve claims about the significance of methods on face value alone. Altheide and Johnson (1994) warn ethnographers of the central importance of accountability in ethno-graphic work. Without an honest accounting of one’s methods and decisions along the path of an emergent design (Lincoln & Guba, 1985), it is difficult to learn the nature of one’s craft, or one’s assumptions. The most positivistic, linear, and deterministic of assumptions can be cloaked in the sheep’s clothing of qualitative methods assumed to be on face value ontologically distinct in their application due to a non-traditional textual form.

This argument is particularly relevant to the presentation of the Four Seasons of Ethnography methodology. The methods that are utilized will be familiar to students and advocates of ethnography. The Four Seasons methodology does not assume to introduce new methods, per se, but rather to demonstrate the application of a variety of already familiar ethnographic methods, along with other familiar methods from introspective and analytic traditions, when rooted in a holistic ontology of circular order. What results is a research process and outcome that is intentionally and necessarily both personally and academically tentative and dynamic. Like the circular progress of a spiral, the researcher and theories develop cumulatively and rhythmically, with no claims of absolute knowledge. Rather, the results are reported with tentative certainty (González, 1994, 1998), a paradoxical term which is characteristic of a respect for the power of nature to determine the circumstances or “facts” of our human experience. Conceptual dynamism, or “new ideas,” are only “new” in that they revisit where we have already been, as fundamental to the ideas’ present and equally dynamic state. History and tradition are fundamental to our current understanding. Theory is not to be refuted or disproven, but contextualized and amplified. Things get bigger, not smaller and tighter, as we understand them.

Guiding Ideals of the “Received View” of Ethnography

When I refer to the “ethnographic method,” I am assuming the array of methods which in consort become both process and outcome of a study of the creation and maintenance of meanings which can serve to identify social groups and their individual members. This creation and maintenance of meanings can happen through (among innumerable others) conversation, nonverbal behavior, routines and rituals (both formal and informal), and even through personal introspection. The methods for its study, however, are fairly straightforward, and the Four Seasons methodology incorporates them: pre-ethnography, ethnography proper (immersion, observation, and interviews utilizing field notes and transcriptions), synthesis and analysis of transcriptions and notes, and the decisions and actions of writing an account of the cultural aspects explored. A classic explication of this sort of methodology can be found in Glaser and Strauss (1967), and Buraway et al. (1991) present a strong collection of the sorts of ethnographic essays that result from solid participant observation ethnography. The following comparison of guiding ideals of traditional ontologically framed work is not a rejection of such exemplary ethnographic works, but is rather a comparative explication, for the purposes of demonstrating how significant decision points in research might end in different ontologically based research strategies and actions.

I borrow the term “guiding ideals” from Guba’s The Paradigm Dialog (1990), in which Guba describes the “ideals” which guide the work within positivistic, naturalistic (constructivist), and critical theory research. The guiding ideal, in effect, serves as an implicit ideological marker by which the researcher can gauge his or her “success” within the given paradigm of research. I have expanded the use of the term to include multiple ideals which exist on a taken-for-granted level due to the cultural situatedness of “Western” research. Guba’s use, I believe, accounts for ideals which characterize the conscious intent of researchers who ascribe to a given “paradigm.” My extension of the use takes into account the very powerful ideals which are driven by cultural assumptions, in such a fashion that they are not recognized as driving ideals, but rather as taken-for-granted reality or nature. The force of these ideals persists, I believe, in the same fashion that one’s primary cultural frames persist and resurface during intense experience.

It is important to mention that the separation presented in these two sets of ideals is itself part of our received view. Although the Four Seasons is presented in this text as separate, care should be taken to note that it incorporates the other as part of the many, many ways in which we experience our realities during the seasons of our experience. As Swimme and Berry (1992) point out:

No experience can be simplistically divided up into inner and outer aspects where the outer aspects … refer simply to the objectively existing universe, and the inner refers simply to the subjectivity … the elements of experience cannot be assigned a simple, univocal origin. (1992, p. 40)

Similarly, it is hoped that the following dualist presentation can be recognized as a heuristic and not as the definition of a battleground of separate opposites. Following are four “guiding ideals” of the received view and also of the Four Seasons ontology.

Received Guiding Ideal #1: Opportunism

This ideal is often discussed under the mantel of linear and material orientations to time and process. I have called it opportunism in that underlying beliefs about the passing of time, including the concepts of “losing” and “wasting” of time manifest themselves in activity for the sake of activity before an opportunity “is lost” or “passes by.” Interviews might be conducted because a member of the culture is present “today” and might not be there “tomorrow,” even if the researcher is not really aware of a purposive need for the interview.

The linear and material orientation to process manifests itself in beliefs that research methods and outcomes should reflect predictable forms. Therefore, if data and observations do not lend themselves to the planned form or design, the form takes precedence over the integrity of the data. Linear and material orientations to time allow for the existence of the myth of “one time” opportunities. Because time can be “lost,” it is important to plan and schedule one’s research. These beliefs, rooted in the same basic cultural assumption, create a guiding ideal that values and rewards “seizing the opportunity” and encourages the perception of “windows of opportunity.” An action orientation to field work develops, in which “doing” something is necessary for it to be regarded as an appropriate “use” of time.

Received Guiding Ideal #2: Independence of Researcher

The idea that the researcher is somehow separate from that being studied, a key epistemological issue, is at the root of this ideal. Culturally, the ability to conceive of such a separation must exist within a belief system that unitizes the world and believes that somehow the separation of entities allows for manipulation of one by another. In many ways, this guiding ideal is actually a necessary condition for the existence of the third guiding ideal, entitlement. The independent researcher can engage in any multitude of activities and relationships while in the field and by implicit definition not consider the effects and implications of the activity on his or her understanding of the culture. The belief in independence allows for immersion research to be understood as “researcher in contact with culture” and not more radically, “researcher as part of cultural context.”

Although much traditional literature on ethnography discusses at great length the reality of involvements and relationships “in the field,” and encourages methods to deal with this, it should be noted that the assumption is that methods are intended to correct and remedy the “problems” which arise when the independence of the researcher is violated (See Stringer, 1996, for an excellent explication of these sorts of dynamics.) Such “violating” influence is not regarded as an integral part of the research process itself.

Similarly, a reaction formation response is possible by those who inherently remain Western in their primary cultural orientation (Hall, 1983), as unpalatable as it might be to some on political or personal grounds. In this case, a hyper-subjectivity and epistemology of involvement is adopted, not as a taken-for-granted position, but as a hypervigilant reaction to the independence position. I have seen this often in graduate students who adopt an ideological opposition to “tradition,” only to reify the validity of the traditional stances through their vehement adoption of “non-traditional” methods. Their reason for the adoption is anti-traditional, rather than organically rooted in a differing ontology. This distinction is precarious, but vital to the understanding of ontology in research.

Guiding Ideal #3: Entitlement

Entitlement is similarly linked to a set of cultural assumptions, in this case, regarding one’s relationship to experience and the world. Social hierarchy is a taken-for-granted, and the human being, translated as self, is seen as in a dominant relationship to that which is external to him or her, including nature and the unusual. Therefore, frustrations exist when this dominance cannot be exercised, as in being able to determine the form and nature of data or experience a priori.

It is manifested most intriguingly on the relation-concept level, a level that exists when one’s access to information is dependent on the cooperative provision of that information by an external party. Since the taken-for-granted natural relationship is one of dominance to anything external to the familiar self, simply having a question is seen as grounds for being able to obtain one’s “answer” upon demand. Curiosity becomes sufficient grounds for entry into a culture and/or community for study. Tanno and Jandt (1994) provide an insightful discussion of these sorts of entitlement dynamics.

Information gathered throughout one’s ethnography is in the control of the owner, as ownership is a manifestation of dominance. Ownership implies ability to control activities, form, or presentation. Therefore, this guiding ideal of entitlement demonstrates itself in any number of issues of assumed access, rights to information, representation, and respect and/or understanding of interpersonal and social boundaries.

It is of interest as well that aspects of the self not known or understood could be seen as unwelcome intrusions, therefore making honest reflection difficult, too.

Guiding Ideal #4: Primacy of Rationality

Spiritual, physical-material, and psycho-emotional experience are made valid subjects of the rational interpretive voice. Historically rooted, the “splits” between the dimensions of human experience are often simplified in discussions as “mind–body” dualisms, etc. The framing of human experience as either mind or body itself implies the primacy of the rational thought as mind, by positioning all other experience within the realm of the body (the physical, emotional and spiritual), with the extreme forms found in physiological explanations provided for spiritual and emotional experience. Given that the paradigm assumes the duality, it is logical that the resulting science would provide explanations which would support the collapsing of categories of human experience (Asante, 1987).

While “in the field,” this can be seen by the insatiable need to explain all things within already accepted categories. It can become extremely problematic when the particular meaning of a cultural phenomenon is so primary to a culture that its members take its definition for granted through its simple or implicit reality to them. The instant that the ethnographer begins, on his or her own, to speculate explanations for these implicit meanings, the rationality of the ethnographer is privileged above the authentic embodied experience of the participants in the culture.4

The primacy of the rational is particularly of issue in the creation of texts that describe cultural experience. Because the written word and many academic forms are rooted in the same cultural assumptions, an authentic rendering of the understanding that might have been attained is made difficult if not impossible. What occurs in the privileging of the rational voice is essentially a veiled repetition of the cultural theme of dominance of the self which operates through the preceding ideals. Ultimately, it will be the interpretation of the rational writer that is assumed as the voice of the “other.”

Guiding Ideals of the Four Seasons

The guiding ideals for a creation-centered circular ontology, as assumed by the Four Seasons methodology are presented below.

Four Seasons Guiding Ideal #1: Natural Cycles (Appropriateness)

The most central guiding ideal is rooted in the belief that all natural experience is ordered in cycles, which are then reflected in the processes and experiences of all living beings. With the Four Seasons, one such cycle is used to demonstrate the circular process of preparation, growth, harvest, and rest with “rest” moving naturally into “preparation” without a fixed point of experiential demarcation.

These cycles are inevitable and multiple, layered upon each other due to the multiplicity of experiential domains, yet all continuing in their natural rotation. For instance, a sudden frost in spring may impede the preparation for growth of crops in summer, thereby affecting the fall harvest, and the nature of winter experience. These natural realities are used allegorically in their application to methodology.

The awareness of this cycle carries with it the interdependent notions of appropriateness and necessity, which can be confused with opportunity if the spiraling nature of circular order is not experienced ontologically. Opportunity is never “lost,” simply delayed for the reoccurrence of a season. This perspective requires that predetermined designs and outcomes be abandoned as dictators of activity. A sensitivity to seasonal cues must develop to appropriately respond throughout one’s research, requiring much of the researcher as a human instrument. If the seeds are not planted at the appropriate time, in other words, allowing for the development of deep analytic skills and awareness-in-practice of the value of all forms of research-related experience, researchers not accustomed to such necessary heightened awareness can find it fatiguing. In the worst cases, researchers might lend themselves to a fatalistic approach in which they avoid the interaction of the human instrument with experience. A balanced system involves a human being who makes wise choices on the basis of awareness of the cycles and their influence on one’s environs.

Four Seasons Guiding Ideal #2: Interdependence of All Things (Awareness)

The interdependence of all things deals with the arbitrary nature of boundaries that we construct for ourselves in our social experience. However, it does not imply by arbitrary that they are unnecessary or without value. Rather, the awareness of the nature of boundaries calls for a further awareness of the obfuscation that occurs if we reify boundaries and perceive separateness where we have constructed it for functionalist reasons.

This guiding ideal will manifest itself most obviously in the seeming disregard for rigid disciplinary and academic dictates of what “counts” as a source of knowledge or information. This is particularly apparent in the formal establishment of one’s expertise, or theoretical sensitivity,5 during which sources of information and insight might come from any academic discipline, from fiction, popular culture and the media, or other non-traditional fonts of knowledge and insight.

In the field, it manifests in the awareness of the inability to compartmentalize experience as “data collection” or “just being there.” Similarly, interviews begin with the first contacts and efforts to schedule an interview and continue with everyday encounters, rather than simply in the asking of formal guided questions. All that exists and occurs within a culture is data and related to the awareness of meanings for the persons for whom it provides primary human grounds for interpretation and execution of experience.

Personal relationships in the field, including those of the researcher with “outsiders,” become related to the study. What develops in one who operates within this ontology is an extension of the heightened awareness referred to in guiding ideal #2. One realizes that all experience is part of the whole process. Therefore, a discipline for one’s life as an ethnographer must develop which respects the process and eventual report as a demonstration not just of the focus of the study, but also of the nature of the researcher, as part of that study.

Four Seasons Guiding Ideal #3: Preparedness

The spiritual traditions of those people whose practices are rooted in the observation and notion of interdependence with nature always have an element present that incorporates the awareness of the nature of cyclic processes. This element is the notion of preparedness, that one simply cannot enter into that for which he or she is not prepared appropriately. A seed will not grow without being planted! This manifests itself in the appearance of personal reflexivity in the reports of one’s ethnographic research, and the value given to rich descriptions of personal and experiential context for one’s “findings.” The coexisting ideal of appropriateness governs implicitly the awareness that an honest and authentic report of context will demonstrate the meaning of those findings, including the interpretations and assumed meanings reported by the researcher. In many ways this guiding ideal incorporates the notion of letting go of control, giving the upper hand to “nature” (see González, 1998). An example of this can be identified when I was studying the sharing of spirituality between non-Indian and Indian (Native American) persons. While preparing, the many layers of my own mixed Native American/Mexican/Spanish ancestry and my corresponding attitudes and feelings about “culture sharing” had to be the object of my own deep reflection and honesty. I relied heavily on members of the groups I got to know throughout the ethnography for their observations on my observations. I could not have done this at a time in my life when I was tightly attached to my identity or opinions as somehow factual. I find graduate students, who want to study major life events while learning methods, are often hampered when they face the reality of their (un)readiness. There is no crime in this—no defect—it is perhaps simply not the season for that topic. The importance of heightened personal awareness cannot be stressed too much.

Four Seasons Guiding Ideal #4: Harmony/Balance (Discipline)

The preceding ideals, with their necessary responsiveness to the awareness of nature and relationships within it, will manifest themselves in the ultimate awareness that all forms of experience must be respected and given attention, due to their interdependent nature. As such, the rational is no more valuable than the spiritual, the material no more significant than the emotional. The awareness that builds due to the belief that all things are interdependent will ultimately lead to the growth of one’s personal discipline and rigor as a human instrument and ethnographic scholar. This discipline will be rooted, not in the expectations of one’s academic field or career, but in the awareness that what is not taken care of now will inevitably be dealt with again in a future cycle of seasons.

One’s methodology in the field will begin to reflect a cyclical awareness of experience within individual events and situations. Field notes and forms of recording experience will respect the natural cycles that the researcher is living. The ultimate report will reflect an insightful selection of what can be reported, and in what form, so as not to upset the balance of meaning.

Ethics are incorporated into this highly intuitive form of discipline. The taken-for-granted requirements for competent and “rigorous” methodology are authenticity and honesty with one’s self as the research is conducted and texts written and shared. The skill of introspection and the ability to accept and process feedback regarding very personal aspects of one’s work are probably the most important attributes of a researcher who functions within this ontology. The instrument in ethnographic qualitative research is, as so well stated by Lincoln and Guba (1985), a human instrument. We, the ethnographers, hold the information, insights, and conceptual turns of our research. We gather the data and process it. Nothing is produced that has not been part of us, as researchers. The research is intimate, organic and interdependent.

This sort of “naturalist” paradigm is best described for me in the writings of Lincoln and Guba (1985). I have adopted and adapted insights from naturalism in my exposition of the Four Seasons. This naturalist paradigm which they presented in their 1985 work could also be called a “constructivist” paradigm (Guba, 1990), or even the “holographic” paradigm (Lincoln & Guba, 1985; Talbot, 1991). Sometimes it is simply referred to as qualitative research. Some might call it `postmodern’. In juxtaposing the paradigm of positivism with these views as I apply them in this work, I have preferred to call the ontology of the Four Seasons a paradigm of paradoxical tentativeness. It is the tentative and paradoxical nature of knowing which characterizes the Four Seasons, due to the cyclical nature of experience and discovery. All “new” knowledge is also paradoxically old, necessarily reflecting all preceding knowledge that led to its discovery. And as the cycles continue, any findings are necessarily tentative. A good example, related to nature, is a weather report.

Lincoln and Guba (1985) do an admirable job arguing that a worldview or paradigm is more than just an alternative perspective. It is not just “standing in a different place.” It is seeing with different eyes. Based on this, all experience, not just the research process, would differ for someone operating from a paradigm of paradoxical tentativeness. One of the most significant differences is found in the subjectivity–objectivity dialectic. The paradoxical tentativeness paradigm places emphasis on the subjective experience, while the positivist places emphasis on the objective. However, within paradoxical tentativeness, objectivity is paradoxically incorporated as a form of subjective experience of equal value to (not privileged above) all others. This is accomplished through the conscious acknowledgement of the functional, yet arbitrary, boundaries, which result in a variety of standpoints. In a sense, boundaries and bracketing of those boundaries (Becker, 1992), are a manifestation of the illusion of objectivity which is necessary to operate within constructed realities. Objectivity in this sense, however, does not imply the lack of influence by external factors, rather it highlights the awareness of the researcher regarding the influence of individual factors. Since all such factors can never be accounted for, boundaries are simply an illusory heuristic for the purposes of cooperative human behavior.

The scholar who operates from the circular paradigm of paradoxical tentativeness acknowledges the human instrument, the researcher as a whole person, as the means of collecting, synthesizing, and analyzing data. In ethnography, the field worker in the midst of a culture being studied, is through his or her experience—physically, socioemotionally, rationally, and spiritually—“collecting data.” Because of this, a profound awareness and understanding of the nature of the constructed boundaries of one’s own identity and personal experience is critical to being an effective “human instrument.” In positivist research, much time is spent in the preparation and “perfection” of a good research instrument. There is a constant awareness that the nature and quality of one’s data and findings is dependent on the nature and quality of one’s instrument. Unfortunately, while there is much romanticism about the human instrument, and much lip service about the need to prepare for one’s ethnographic experience, there has been little yet existing that approaches what might be adequate forms of preparation of the human instrument, as required by the circular ontology of paradoxical tentativeness (for an exception to this, one might look at the work of Goodall, 2000).

Viewing the ethnographic process from a creation-centered cyclical perspective provides a means for framing one’s preparation for fieldwork. By using this approach, I have also found a means for framing the entire ethnographic process—it is a spiritual enterprise, situated in a human context (González, 2003). As creation-centered, I have chosen to view the ethnographic process through the cycles of the Four Seasons of nature. Creation-centered cultures share a close relationship with nature, and with the yearly cycles that govern life. Spiritual and social rituals reflect those cycles, respecting the interdependence between all things. Depending on geography, the seasons may have different characteristics, but cycles still exist, and at all levels of experience. This holographic reality is today being recognized by scholars and technologists (Talbot, 1991). When someone is culturally predisposed to view things ontologically and paradigmatically as circular and paradoxically tentative, the assumptions behind the Four Seasons will not be problematic; they are in sync with reality. For others, culturally “Western,” linear and objectivist in their assumptions about reality, the Four Seasons will be a serious challenge to learn. But as many persons not culturally “Western” seem to succeed at mastering methodologies foreign to their ontologies and implicit paradigms, I believe the methodology of the Four Seasons can be learned—but hope that it might be a less traumatic experience.

I personally believe that the experience reported by many underrepresented groups in the academy, who have been forced into conducting and reporting their ethnographic work through lenses of an ontology and paradigm that is in discord with their own, is an example of the trauma which can occur if forced to repeatedly prove one’s value as a scholar through an alien ontological position (see Padilla & Chávez Chávez, 1995, for graphic narrative accounts of Latina/os in U.S. higher education). For this reason, I personally do not believe it ethical (or sound) to expect persons to totally “deconstruct” and eliminate the present ontology or paradigm as requisite for acceptance as a member of the academy or one of its subgroups.

This much said, I believe that because the ideals of the positivist paradigm and its resultant ontology predispose persons to believe in the existence of truth vs. non-truth, any other way of looking at the world will tend to be viewed as inferior through those lenses crafted to perceive dichotomies of value. As such, I can understand why some would move to “eliminate” the positivist paradigm. This desire is a residue of positivistic thinking. Paradigmatic change should be voluntary, based on the gradual awakening and changing of individuals and society. Imposition would simply be a replication of the hierarchical domination already present. With paradoxical tentativeness, even forces experienced as oppositional and destructive or dominating reflect something of the interdependent cyclical world in which we live. To deny the reality of variance is foolish, nor can we control it any more than we can control tornadoes or earthquakes.

It is the application of the methods within a paradigm that often demonstrates the ontological positioning of the researcher. I believe that the Four Seasons methodology is very compatible with what I have read concerning the naturalist/constructivist paradigm. Paradoxical tentativeness and holographic interdependent realities are difficult to handle, but especially so if one does not implicitly operate in his or her world according to these ideals. Just rationally or intellectually “agreeing” with a concept, or “seeing its point” is not the same as taking it for granted in the application of one’s research methods.

In order to present the Four Seasons in a language that will trigger fewer predisposing constructs, I will largely abandon social science style in writing in favor of the language of ceremony from creation-based cultures that do indeed have a circular ontology. I gather much from my direct experience in ritual. What follows in an attempt to describe the essence of a Four Seasons approach to methodology.

The Nature of the Four Seasons

In creation-centered traditions, ceremony is much more than the ritual proper. Ceremony involves phases, which like seasons, reflect the natural process of the ceremony, itself reflecting the cycles in creation. There is a preparation, or spring, as I will call it, which is the foundation for all that will come. It is followed by the summer, or actual recognizable ritual acts. The fall, or harvesting portion of a ceremony is the time when the fruits of the ceremony are shared and celebrated communally. The winter is the time of rest and waiting, and it is often the time when the meaning of the ceremony is received and understood. The phases of nature can be observed to provide wisdom about the phases of all human experience. What follows is a description of the ethnographic process using the four seasons to highlight the methodology and significance of the season to the overall ethnographic project.

Spring

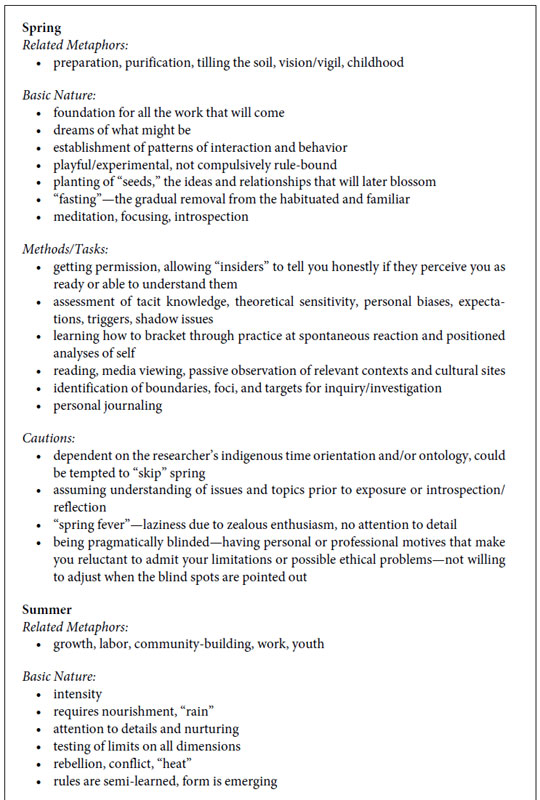

Like the fast of the firstborn before the first Passover seder, or the fasting and ritual purification before the traditional Lakota hanbleceya,6 the spring of ethnography is that time during which the ethnographer must prepare for what is ahead (Figure 10.1). It is the foundation of all the work that will come. During this time, there is much speculation and dreaming about what the ethnographic project will be like. The future is uncertain, and there is excitement, anticipation, and often some reservation. In the traditional ways, one is a fool not to have some measure of fear. It demonstrates a lack of respect for what is about to be experienced. Likewise, not having some measure of fear about one’s ethnographic experience demonstrates immaturity and serious naiveté concerning the entrance into the lifeworld of others.

In some ceremonial traditions, it is necessary to ask permission to be allowed to participate in the ceremony. Preparation cannot begin until that is granted. Often, in the Western social scientific traditions, there is an assumed “right” to study what one is curious about. From the perspective of the Four Seasons, this is always presumptuous and disrespectful, demonstrating clearly the inappropriateness of timing for the research. In creation-centered traditions, a demonstration of sincere respect is of utmost importance. This respect might be demonstrated through patient waiting to receive word that one can participate. Some people wait years to know that the time is right to participate in a ceremony. Similarly, just knowing that you want to study something does not mean it is the right time to do so. Respect is about “looking at something again,” getting to really know it. It is not about rushing.

Figure 10.1 Synthesis of Integral Concepts for the Four Seasons of Ethnography.

During the spring, the human instrument is being prepared for fieldwork. This is a time for much introspection and honest observation of the self. What are your strengths and flaws? This will tell you much about your methodological preferences and choices once you are out in the field. The blatant extrovert, for example, will often want to rely mostly on interviews and conversation, while the more introvert researcher will want to be an unobtrusive observer. By honestly accepting these bits of information about the self, you can prepare for your study, knowing what other types of data you will need to strengthen your work, knowing what methods will best triangulate with what you personally prefer. Personal “flaws” are not problems. They are what characterize you. What you think is a flaw simply tells you what is culturally valued, not what is “wrong with you.” They are guides that lead you in the direction of what you might need. Because of this, the ethnographer who refuses to see his or her own characteristics, both positive and negative, is limited. Denial guarantees that you will not see the weaknesses in your method, because you do not see the weaknesses in your instrument—you.

During the spring of ethnography, you should honestly assess your biases. Unlike positivist research, biases are not problematic. They are part of your subjectivity, and they provide insight into the unique perspective that you will provide in your ethnography. Without an awareness of them, however, you will not know what your perspective is, and neither will your eventual reader. It will weaken your finished work. Some examples of work that have been done utilizing this ontology are those of Krizek (1994), Stage (1997), Broadfoot (1995) and Mendoza (1999).

Further introspection should guide you to look for your limitations and boundaries in terms of what you are personally capable of stomaching and tolerating. This will tell you what the scope of your study can be. Because as tentativists we do not pretend to represent whole populations with our work, it is not necessary that we have a scope that specifically accounts for all aspects of a culture. The holographic nature of reality will interestingly enough provide you with information about the breadth of the culture if you are watching carefully, with an eye of wholeness rather than separateness.

Respect others. Boundaries, because they are socially constructed, are there for a reason. Crossing them has implications -a price- and you will pay it, one way or another. In traditional ways of creation-centered practices, violating order in a ceremony is a grave transgression that carries a spiritual, if not physical, price. There are things that can and cannot be done. During the spring of ethnography, we listen to others who have gone before us and know of the culture. They can help us to identify the rules. We are not all-privileged in all situations. Research does not entitle us to be able to enter, ask or do as we wish. Like in a ceremony, there are limits and boundaries of appropriateness. Spend time identifying them. Listen when they are identified to you by others, and respect them. One of my students learned this very powerfully when in her curiosity while in a sweat lodge in Porcupine, SD, taking an ethnography class in field methods which I was teaching, she attempted to approach the man who was running the ceremony. He very curtly informed her that it was not to be allowed—ceremony time was not the time for doing anything but ceremony.

Search your heart. This is very important, and is perhaps the most important aspect of preparation. Why are you doing this? A traditional medicine person will turn you away if you do not at some level know why you want to participate in a ceremony. If you don’t know why you want to study something in this highly intimate way, then maybe you aren’t ready. Spend more time reading, studying other things, learning about yourself. If you are impatient or rebellious, take time to figure out why. You are about to enter into other people’s life worlds. Be honest about your motives, even if they are embarrassing. Don’t do it disrespectfully. And this goes for looking at your own life as the subject of ethnography as well! It is a grave disrespect to participate in a ceremony “just to see what it’s like,” or to talk about it publicly just for the attention. There has to be a conscious spiritual reason, not just an assumption of spirituality. Likewise, in ethnography, what is your reason? And be honest. If you don’t know what your reasons are, you aren’t ready. Learn to wait. Sometimes, the ethnographic process will startle you if you cannot answer this. One student, while coding her field notes, was stunned when her biases against men became glaringly apparent in that she had not included any codes of negative experiences of women in a matriarchal society. She was forced to see that she had an underlying agenda for the study, which, had it not been recognized when she submitted her codes for grading, would have led her to write a report that systematically distorted what she experienced.

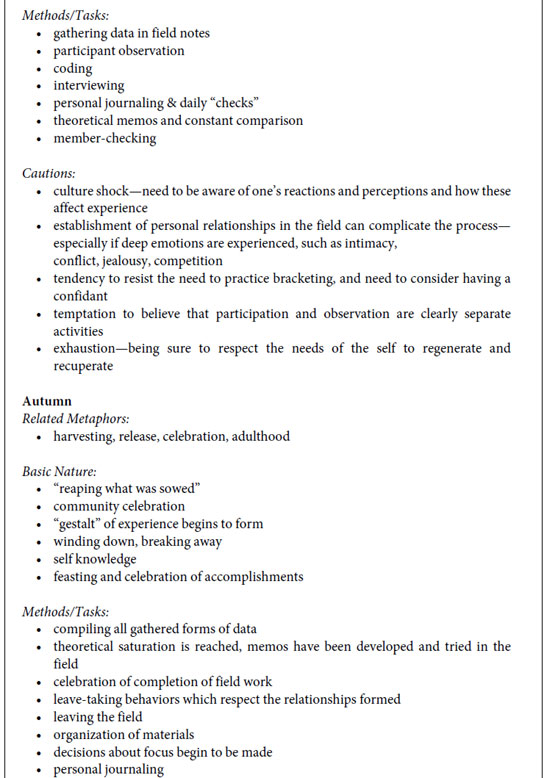

Summer

Just as with seasons, one wakes to the summer of ethnography gradually. It is an emergent progression from one fluid state to another. Suddenly one day you realize that you are in the midst of field work proper; you are no longer preparing. This emergent realization is only possible if preparation has been adequately conducted, for spring is actually a gradual entry into the field, a sort of “pre-ethnography.” If this pre-ethnography has not taken place, then one feels a jolt with what can be a violently rejected culture shock. What is considered a normal part of field work from a traditional academic perspective (culture shock) is a sign of not being able to be present where you are. Preparation in the spring should teach you how to handle this more appropriately, so you can handle the culture shock better. You cannot force seasons to change, and from this perspective you cannot begin your work until it’s time.

During the summer, it is the time to maintain steady involvement with the culture. It is the time for discipline, but not as in traditional conceptions of rigor. Discipline here implies that you have become a disciple of the culture. You are learning it not as an outsider, but in order to be part of it, as yourself. It is never the same to merely watch a ceremony as it is to participate in it. The level of depth of understanding you can attain through this type of participation is true understanding rooted in experience. And you need not change yourself. Change occurs naturally—when it doesn’t, it is a form of violence. Summer is a time of intense realizations.

It is this intensity, this “heat,” which will determine how the rest of the year will proceed. Like an all-consuming summer heat, it cannot be escaped, even at night when alone in bed. This is what true immersion fieldwork is like. That is what is so frightening and threatening about it. It is during the summer that one is most apt to want to cry, “I wanna go home!” but not out of culture shock. Rather, like in a ceremony, because heat makes one quickly realize what is really involved. Making it through the summer of ethnography means working even when fatigued, heat-exhausted, and weary. This fatigue will be mental, emotional, and spiritual as well as physical.

The skilled ethnographer in the field learns to believe in the circle of time, in the inevitability of changes. If there is too much focus on one’s specific experience, the product of the ethnography will be narrow and non-holistic. It will not capture the essence of the culture. Rather, each and every experience within the culture is an example of the whole culture. And the essence, therefore, is tentative and paradoxical. Wisdom begins to grow from this aspect of summer, as fruit that reaches its full size and begins to ripen. The Sun Dancer in Lakota tradition learns the meaning of his or her people through the dance. The dancer who focuses on his or her thirst rather than the dance, cannot understand its essence anymore than an ethnographer who focuses on specific behaviors and the recording of those specific behaviors can understand that which gives them meaning—the context, the culture.

Summer is a time of paradox. The heat makes the body naturally lazy, but work at the same time must pick up if one is to be ready for fall. Because of this, work during the summer of ethnography must always be tempered by efforts to conserve energy. The amplitude of experience that offers itself in the summer provides the ground for learning one’s limits as a human instrument. As relationships build and fatigue grows, the potential for conflict and confrontation of personal biases increases. It is in the summer that the idealized “subjects” in the field lose their romance. They become people -ordinary people with human frailties and faults. It is in this aspect of the summer that the value of honesty during the spring can best be appreciated. Having “sold” one’s self to get access by making the human instrument seem “too good to be true,” or denying the reality of one’s limitations, will become apparent as the immersed human instrument shows his or her humanity along with that of the native members of the culture. The irony is that it is the conflict that begins to arise here which is integral to obtaining a true understanding of another culture.

Until one learns to engage in conflict and stay, one does not know what members of a culture are like. The does not mean watching conflict between others, it means accepting one’s own involvement in conflict as a member of the social dynamics of the field. It means perceiving this conflict not as a “methodological issue,” but as lived cultural experience. Not only the enjoyable or entrancing is worthy of our attention. I remember the problems I had with my landlady during the early stages of ethnographic work in Mexico in the fall of 1998. She lectured me daily on religion and morality, and when she found me buying a gift bottle of tequila in a grocery store, she snatched the money out of my hand and attempted to influence my behavior. I spent much time interviewing other women informally about this encounter, and in the process, learned much about the roles of women in conflict in Mexico. Rather than try to explain my position ad nauseum, I tried to find out why they found the situation to be permissible, although aggressive. This was not an enjoyable phase of my ethnography, but vital.

Having planted one’s crops and leaving them when they begin to be choked by weeds is not the way to prepare for a good harvest. It is similarly the undesirability of one’s work that tests the human instrument’s ability to obtain the “data” which will allow an ethnography that demonstrates true understanding to be written. It is always possible to alter one’s tasks by focusing on journals and note-taking, on categorizing and interviewing, during this phase. The seasonal approach to ethnography sees those enterprises as important, but not central to one’s work. What is central is the involvement with the culture, and although we have called it “immersion” into a culture, it is more like infusion. The human instrument must be steeped in the culture, allowing him or herself to be transformed through the research. Only through this transformation will he or she ever understand the culture implicitly. This is what will enable him or her to write the essence of a culture rather than describe it.

What is needed in the summer is the ability to let the indigenous participants in the culture teach the human instrument how to function as a human being in their world. This is not in order to understand them as “subjects,” but to fully participate as one’s self in their world. This means that aspects of his or her personality and preferred ways of doing things will need to be put aside for the duration of the research. One learns to make choices within the cultural frame—sacrifice and laboring are needed. This is not in order to demonstrate skill or endurance, but because the human instrument is gathering data in the way he or she best does it -through experience. It becomes part of him or her. I once heard the head dancer of a Lakota Sun Dance joking with a group of non-Indian dancers after a particularly grueling day of dancing, “Put that one in your book, Jim!” At another time, he added, “Some things aren’t able to be known ‘out there’ with pictures and words; some things can only be known inside.” When the human instrument begins to know this intuitively rather than intellectually, fall is approaching.

Fall

The intuitive sense of knowing in an implicit unexplainable way is as comforting as the first cool breeze of autumn after a long hot summer. Autumn is the cool down; it is exhilarating and intoxicating to reach a sense of completion that is dangerously misleading. The year is not over, but it feels as if the work is. This is the stage when the ethnographer needs to concentrate on his or her task, because it is at this point that winter is anticipated. And winter is the deadliest of seasons if one is not prepared. Winter will be the time of writing and publishing, of sharing one’s work publicly. Without a good harvest, one’s efforts will be for naught.

In the autumn of fieldwork, the human instrument begins to reframe the experiences of the summer. Instead of saying, “I wanna go home,” he or she is more apt to say, “I don’t know if I wanna go home.” Having made it through conflict with members of the culture, there is apt to be a sense of bonding and comfort with the “host” culture. This is when it is tempting to believe that one has actually become a member of the culture. While decisions to continue relationships with members or aspects of the cultures studied may indeed be part of the life experience of many ethnographers, caution needs to be taken as a researcher during the fall. The ethnographic task from a circular, holistic perspective is to understand the culture as a whole. By being lured into purely subjective personal experience with no “eye” for the whole picture, the ethnographic task is endangered. This is when one’s journals and notebooks again become important. Summer’s tasks are misleading in that they could lead one to believe that that is when note-taking is most important. From this perspective, it is actually autumn when most notes should be recorded. It is during autumn that theoretical memos should be written and necessary interviews conducted. It is the time to harvest. And this is a harvest from within the human instrument.

During autumn, the researcher should know enough about the culture to know what is being analyzed. Earlier, in the spring, the focus was on preparation of the instrument. In the summer, it was on learning the culture. Once both seasons have passed, memos can be written. From a holographic perspective, there is no problem in recording events at this time, and not only when in their midst. It does not mean that no notes can or should be taken during the summer, but merely that it is not the sole time, nor always the most appropriate. With repeated experience in the field over years, one’s memory will begin to develop in ways that will facilitate harvesting in the fall. The fruit gathered in the summer is far from ready for harvesting. One must wait until fall. Clarity of one’s experience is a characteristic of a well-prepared fall, like crisp clear autumn nights. Now, decisions on the perspectives for analysis must be made.

From a creation-centered perspective, all knowledge is valuable, but wisdom is only attained from completion of cycles. The insight of wisdom into a culture requires tenacity and willingness to wait until one is ready to “know.” And even then, “knowing” is tentative. It is during the fall that the temptation will grow to believe that one has certainty about the culture. That is why I have formulated the concept of “tentative certainty” to characterize the knowledge acquired through creation-centered ethnography stemming from a circular ontology. Rooted in relativity, tentative certainty respects the boundaries of subjective context as determinants of what is known. During the fall, the ethnographer begins to create categories for what he or she has experienced, and to chronicle experiences within those categories. Categories are related to each other in explanatory expositions called theoretical memos (Glaser & Strauss, 1967). But at all times, these relationships and category assignments are subject to redefinition; they are tentative. Practicing this frame of mind during the autumn prepares one for writing in the winter. One’s writing cannot reflect tentativeness if the writer does not intrinsically experience it. It is not being “wishy-washy” or noncommittal; it is the ability to believe something wholeheartedly without being attached to it. Learning how to detach one’s self from things held dear, including one’s ideas, was at first practiced in the spring by bracketing one’s biases and limitations. Later it was practiced in the summer by learning to continue in endeavors when one does not rationally want to continue. In the fall, it is practiced through expressions of tentative certainty. All three seasons ultimately prepare for winter.

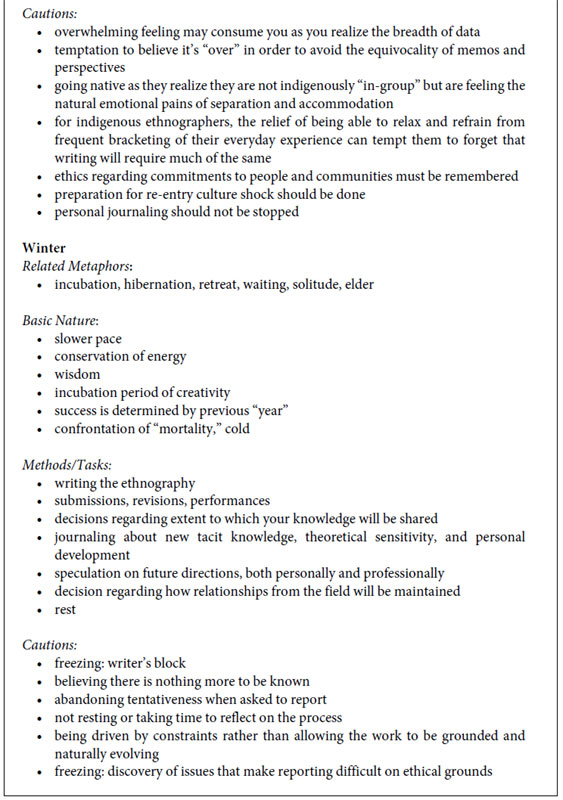

In the winter, the researcher “leaves the field.” In classic fieldwork, this is meant literally. The researcher breaks away physically from personal contact and presence. This may or may not be the case with indigenous ethnography, but the human instrument must still somehow break away from dynamic lived experience to write about it. The very act of recording in writing the essence of culture changes it to something it is not. It freezes it. And the possible deathly consequences of winter’s deep freezes are excellent metaphors for the costs of careless writing.

Writing about a culture, even when one is or has become a member of it, always involves leaving the culture in one’s mind. This is why during the winter of ethnography, I believe it is necessary for the human instrument to physically retreat. This is not in order to leave one’s subjects and setting, but rather to contemplate the separations one will create with writing. Some might call this “considering ethics.” But the issue is not whether one is right or wrong ethically—it is considering what will be given back to the people with one’s work. It is time to consider what the human instrument has experienced subjectively. It is a time to anticipate one’s future life, having been through the ethnographic experience. It is a time to journal honestly while simultaneously explicating one’s theories and ideas about the culture.

In the winter, the human instrument cannot become so absorbed in his or her work that the self is neglected. Winter is a cold time. It is often lonely. Writing about a culture removes you from it, so that even if you are part of it, you no longer are in the same way. This is the winter of ethnography. Even if relationships established in the field are maintained, writing about it in a way that will become public transforms the writer. The human instrument has done something which will reflect back on him or her, and the culture about which is written. In traditional creation-centered societies, this is at the core of justice without need for elaborate legal systems. If what you do will reflect back, or come back, to you, then actions must logically be careful. What one writes about the people will inevitably come back to the writer in his or her life. It is not a light enterprise. In fact, it is quite serious.

Words are sacred in creation-centered traditions. They create realities with which we must live. Discussing open systems in human communication, we sometimes talk about irreversibility. In traditional creation-centered views, it is not just that something cannot be reversed; it is that whatever we say will keep moving along the circle of life and come back to us. Words are spiritual—they carry with them power and energy which lives through them. It is this spiritual force of words which enables them to create reality. It is also the reason behind the unwillingness of traditional native people to speak when they have nothing to say. Similarly, the human instrument should write to say something. One should not express out of obedience or strict obligation; one should express only when there is something to say. Accordingly, what is expressed by someone who truly believes it, is serious. It is not taken back. It has been ex-pressed, sent out, with an understanding that its spiritual force will come back to the sender.

This is what winter is all about. It is the culmination of all that the other seasons have involved. And it, like the other three seasons, can last for a very long time. One should not be tempted to think that the annual aspect of the seasonal metaphor implies that the Four Seasons of Ethnography reflects a calendar year. The Four Seasons highlight many real aspects of a creation-centered approach to ethnography, but the seasons of a year are fairly fixed in terms of their duration. In ethnography, the duration of seasons is determined by the subjective, spiritual experience of readiness on the part of the human instrument during a cycle that has its own rhythms.

This intuitive sense of knowing when to “go on” to the next season means that one’s work may not correspond to formal organizational requirements. But if we are honest with ourselves, formal organizational requirements rarely are natural. The Four Seasons propose an approach to understanding other cultures that is creation-based, organic, and not imposed. It requires new definitions of academic performance. For example, I believe that the well-developed and supported theoretical memo must begin to be recognized as a viable contribution to scholarship. Similarly, entries from “spring journals” must begin to be accepted methodological reports. By allowing work that reflects the progress at all seasons to be recognized as the viable scholarship it is, ethnographers who use the Four Seasons approach to “govern” their research would find they can be productive even before the ethnography is “done.” All seasons are beautiful and sacred in their own way. To stress the works of one season above another is to work in an unbalanced way. When there is a lack of balance, something will fall or break eventually. By choosing to do ethnography as a reflection of the natural, organic, order in the universe, I am choosing to do my research in a way that allows me to maintain balance and harmony.

Maintaining balance in this sense does not mean eliminating conflict. Harmony does not mean carefully orchestrated synchrony. Balance is the precarious experience of dynamic tension, with the constant awareness that “things could tip” at any point in time, if a move is made too abruptly or too dramatically with too much force. From a state of balance, all actions are “weighed” with regard to their effect on the balance. It is not a position of comfort. It is the position of dialectic tension, of the constant awareness of opposites. Balance is the union of those opposites, and rather than eliminate the tension, it is the experience of it. Similarly, harmony is like the morning song of birds waking to the new day. They all sing different songs at the same time, at different paces, but with respect to each other’s song. All come through. To do ethnography from a place of harmony does not mean it is without conflict or challenges or displeasure. It means that the goal of one’s voice is authenticity and mutual participation. In order to do this, all the seasons must be lived fully. From this position, one would eventually come to the place of not having to ask oneself, “Why do I do what I do?” When balance and harmony become a way of life, then one’s work is merely an extension of it, and its purpose is not compartmentalized as distinct from other aspects of life (Fox, 1994). Harmony and balance exist when individuals are themselves, and when they act from a confident awareness of that knowledge. Our ethnographic work begins to answer, not the demands of structured organizations or careers, but the question of a source far greater—a question that asks, “What is the reason for which I am called to do this work?” (Kamenetz, 1998). Imagine if birds, if trees and four-legged animals, waited for their career plans to tell them what they should do next!

Native, creation-centered people living traditional earth-based lives, have always learned how to act organically—by watching nature. Many of the traditional tales and stories of animals are reflections of the awareness developed of archetypal organic ordering (Taylor, 1998) that is developed from observing and living an experience of creation, of nature. As such, animals and plants are seen to have the same potential as humans and vice versa. This approach to looking at members of “other” cultures has much to offer those who have been overly affected by the notions of scientific objectivity and the myth of possible separation of parts. Everything is related, and therefore what we do in our work with others will inevitably be done to us.

Afterward

There is an old Hopi story about Coyote and her efforts to get food for her pups. On one of her ventures, she encounters a sacred kiva, and she is overcome by curiosity. Her curiosity is so great that she violates norms in order to look into the hole on top. What she sees is lots of people—four-leggeds, birds, humans-all learning how to transform themselves into other creatures. Twice, their magic is interrupted because they realize that someone is watching, and they search for her outside the kiva, taking time from their normal activities to stop the interference. On the second search, they find her and take her in. They might as well—she has already seen them at work. Coyote is asked if she would like to learn their secret. She decides she will become a rabbit, because then she could run much faster and catch her prey. Like the others, she jumps through a hoop and is transformed into the animal she desired to be. They then tell her to go on her way and to come back another time, when they will tell her how to return to her previous form. When she leaves, the others laugh at her naiveté and ignorance. Imagine, they think, she actually thought they would tell her all their secrets! Meanwhile, Coyote runs home in the form of a rabbit, and upon arriving home to her hungry pups, they eat her.

Ultimately, her own were the ones who suffered from her venture. Had she only tried to live her own life, rather than attempting to know what was not meant to be her knowledge—by attempting to do her work in the form of another. There are many lessons here for us as ethnographers if we will only pay attention to the creation around us.

Notes

1.I use the term indigenous to refer to a cultural conceptual “place” of origin, as opposed to specific physical location or nation-state identification.

2.Native American peoples, as I use the term, includes those cultures that populated the lands from what is now Arctic Canada and Alaska to the southern tip of South America, prior to the arrival of European refugees, conquerors and settlers.

3.One who observes in order to judge or give an opinion.

4.This would seem somewhat less likely in an indigenous ethnography, if the ethnographer were particularly reflexive and possessing a high awareness of his or her own culture. The strength of the received view is demonstrated in that academic socialization can function to distance a cultural member from his or her own culture.

5.This formal academic preparation which utilizes theories and literature to serve as a backdrop for awareness I refer to as theoretical sensitivity, broadening the use of the term coined by Glaser and Strauss in their 1967 work, The Discovery of Grounded Th eory.

6.Literally, “crying for a vision,” the Lakota ceremony popularly called a “vision quest,” which entails being placed in a pit or up on a hill to await one’s vision.

References

Altheide, D. L., & Johnson, J. M. (1994). Criteria for assessing interpretive validity in qualitative research. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative research (pp. 485–499). Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Asante, M. K. (1987). The Afrocentric idea. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press.

Asante, M. K. (1988). Afrocentricity. Trenton, NJ: Africa World Press.

Asante, M. K. (1990). Kemet, Afrocentricity and knowledge. Trenton, NJ: Africa World Press.

Banks, A., & Banks, S. P. (Eds.). (1998). Fiction and social research: By ice or fire. Walnut Creek, CA: AltaMira Press.

Becker, C. S. (1992). Living and relating: An introduction to phenomenology. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Bickerton, D. (1992). Language and species. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Bickerton, D. (1996). Language and human behavior. Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press.

Broadfoot, K. (1995). Theory of a faceted cultural self: The role of communication. Unpublished master’s thesis, Arizona State University, Tempe, AZ.

Browning, L. D., & Shetler, J. C. (2000). Sematech: Saving the U.S. semiconductor industry. College Station, TX: Texas A & M University Press.

Buraway, M., Burton, A., Ferguson, A. A., Fox, K. J., Gamson, J., Gartrell, N., Hurst, L., Kurzman, C., Salzinger, L., Schiffman, J., Ui, S. (1991). Ethnography unbound: Power and resistance in the modern metropolis. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Capra, F., & Steindl-Rast, D. (1992). Belonging to the universe: Explorations on the frontiers of science and spirituality. San Francisco, CA: Harper.

Daly, J. A., McCroskey, J. C., Ayres, J., Hopf, T., & Ayres, D. M. (Eds.). (1997). Avoiding communication: Shyness, reticence, and communication apprehension (2nd ed.). Cresskill, NJ: Hampton Press.

Daly, J. A., McCroskey, J. C., Martin, M. M., & Beatty, M. J. (Eds.). (1998). Communication and personality: Trait perspectives. Cresskill, NJ: Hampton Press.

Denzin, N. K. (1997). Interpretive ethnography: Ethnographic practices for the 21st century. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Ellis, C., & Bochner, A. P. (Eds.). (1996). Composing ethnography: Alternative forms of qualitative writing. Walnut Creek, CA: AltaMira Press.

Fox, M. (1991). Creation spirituality: Liberating gifts for the peoples of the Earth. San Francisco, CA: Harper.

Fox, M. (1994). The reinvention of work. San Francisco, CA: Harper.

Fox, M. (1996). Original blessing: A primer in creation spirituality. Santa Fe, NM: Bear & Company.

Glaser, B. G., & Strauss, A. L. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. Chicago, IL: Aldine.

González, M. C. (1994). An invitation to leap from a trinitarian ontology in health communication research to a spiritually inclusive quatrain. In S. A. Deetz (Ed.), Communication yearbook 17 (pp. 378–387). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

González, M. C. (1995). In search of the voice I always had. In R. V. Padilla & R. Chávez Chavéz (Eds.), The leaning ivory tower: Latino professors in American universities (pp. 77–90). Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.