CHAPTER

FORTY-TWO

CONVERTIBLE SECURITIES: THEIR STRUCTURES, VALUATION, AND TRADING

Managing Director

UBS Financial Services

Convertible debentures and convertible preferred shares, or more generally equity-linked securities, span the space from common stock on the one hand to nonconvertible (straight) debt on the other. While the majority of newly issued convertible securities combine a balance of the common stock and straight debt attributes, some are close proxies for common stock and others skewed toward straight debt. Some new issues may have maturity of as short as three years, as in the case of convertible notes and mandatorily convertible securities, while traditional convertible preferred shares are perpetual; that is, the issuer is not ever required to repay the par or the principal amount of the security. The vast majority, though, have maturity dates ranging from 5 to 30 years, with 5 to 10 years being the most common. Over time, a convertible security that may have started out as very close to straight debt may become very much like common stock due to price appreciation in the common stock into which it is convertible, called the underlying stock. The reverse is also true as the price of the underlying common stock declines.

Convertible securities have evolved significantly along with the market’s sophistication in analytics, trading, and attention to risk. This chapter will examine the products that comprise the asset class, its evolution, motivations for their issuance and purchase, and their structural aspects. A substantial part of the chapter will focus on valuing these securities, colloquially known as convertibles or converts. Passing reference will be made to convertible markets in the other regions, namely, Europe, Japan, and non-Japan Asia.

The essential features of convertible products, and notable exceptions thereto, are as follows:

• A convertible security may be converted, generally at any time until its maturity date, into the underlying common stock. Exceptions: some converts may have an initial nonconversion period of 6 to 12 months, sometimes longer. Some may have a Contingent Conversion clause whereby the conversion right of the investor only commences upon the underlying stock price exceeding a threshold price, usually ranging from 25% to 50% above the then effective conversion price, for a prespecified number of days.1

• The vast majority of convertibles are convertible into the shares of the issuer. The rest are convertible into shares of another publicly traded entity. These latter securities are called exchangeables.

• The conversion right rests with the investor. Exceptions: in mandatorily convertible securities, investors are not given a conversion option; they receive the applicable shares mandatorily at maturity. Some nonmandatorily convertibles may have a knock-in automatic conversion subject to the underlying stock price exceeding a threshold price for a prespecified number of days.

• Almost all converts have a redemption feature that allows the issuer to redeem them prior to maturity. Exceptions: some traditional convertibles and most mandatorily convertibles are nonredeemable.

• Even if convertible at any time, investors are likely to exercise the conversion right only in response to a redemption notice by the issuer—also known as the issuer redemption or issuer call, or simply, the call. In other words, virtually all conversions occur only when forced by the issuer. Exceptions: (a) when the underlying stock pays a high dividend and is also illiquid, e.g., Real Estate Investment Trust Stocks; (b) in the presence of material market friction such as future restrictions on conversion or it is costly to borrow the underlying stock to sell it short as a hedge; and (c) when the underlying stock price is above the critical stock price, discussed in further detail below.

• Upon conversion, the issuer will usually satisfy its obligation by transferring to the investor the specified number of shares of the underlying stock per convertible. This is called a physical settle. Exception: Sometimes the issuer may have the right, specified in the prospectus for the convertible, to satisfy its obligation by paying the investor the cash value of the underlying securities. This is known as the cash settle option. Depending on the liquidity of the underlying stock, a cash-settled convert may fetch a slightly lower price than would a physical settled convert due to the cost incurred by arbitrage and hedge fund investors in covering their stock short position. With some exceptions for deep-out-of-the-money convertibles, hedge funds short the underlying stock against a long position in the convert. In some instances, conversion is specified into a combination of the underlying stock and cash, or a specified combination of stocks or a choice among specified multiple stocks. The last case is called a rainbow conversion option, wherein the investor has the option of converting into that stock among the choices provided that results in the highest value upon conversion.

• A convertible’s current yield or yield to maturity or yield to first put usually exceeds the dividend yield of the underlying stock.

• The price of a convertible is at least equal to the value of the shares into which it is convertible, that is, its conversion value. In other words, a convertible should trade at a non-negative premium to its conversion value. Exceptions may occur under the following conditions: (a) when there are restrictions on the investors’ conversion right; (b) when the underlying stock is illiquid and the cost of borrowing the stock is high; (c) in anticipation of forced conversion leading to a loss of the accrued coupon—this feature is colloquially known as the screw clause—a currently redeemable, deep in-the-money, convertible may trade at a discount to its conversion value; and (d) in the case of cash settled convertible, which may cause additional transaction costs for arbitrage and hedge fund investors.

• Convertible debentures are most commonly issued as subordinated debentures, although senior subordinated and senior unsubordinated debentures are increasingly more frequent. Unsubordinated convertible debentures are generally the rule in Europe. When issued as either subordinated convertible debenture or convertible preferred, they are accompanied with relatively fewer restrictive covenants.

• Convertibles have a prespecified maturity. Exceptions include: (a) A handful of mandatorily convertibles whose maturities may be extended by a year at the option of the issuer; and (b) the “PHONES” convertible product (described below), in which maturity may be extended by as long as 30 years.

• Convertibles have a prespecified number of shares per convertible, i.e., a fixed conversion ratio. Exceptions: (a) The number of shares received upon conversion of a mandatorily convertible security is not fixed, but is a function of the underlying share price on the settlement date. However, the number of shares to be received is bounded by prespecified maximum and minimum limits; and (b) some Japanese and non-Japan Asian converts have a reset or refix clause whereby the conversion ratio is adjusted upwards, and the conversion price adjusted downward if the underlying stock price does not exceed prespecified trigger prices.

Evolving sophistication of convertible issuers, investment bankers, and investors has changed the convertible market in several key ways. Higher interest rate volatility has highlighted duration risk and convexity inherent in any security with a fixed income component, including converts. The increased volatility of corporate spreads (over U.S. Treasury or LIBOR or other interest rate benchmarks) resulting from concerns about corporate defaults as well as defaults by countries—the sovereign defaults—has heightened investor sensitivity to default risk. The consequent emergence and importance of credit default swap (CDS) as an instrument for risk transference for corporate and sovereign issues can hardly be overemphasized.2 The volatility in corporate spreads, in the context of converts, raises concern regarding the reliability of a convert’s estimated fixed income floor or bond value. As a result, to arrive at a better estimate of the bond floor and hedge against the default probability of a convert, CDS pricing level applicable for the issue and its trading have very quickly become integral parts of convertible valuation and arbitrage.

Convertibles have equity and interest rate options, and occasionally, currency options, embedded in them. The value of these options is a function of, among others: (a) Equity volatility; (b) interest-rate volatility; (c) spread volatility; (d) default probability; and (e) recovery value in the event of default. Except in some simple situations in which options embedded in a convertible are separable and therefore can be valued using simple models in an additive mode, in the vast majority of cases the options interact with each other and are not separable. Investors should, therefore, be aware of the inherent danger of attempting to value the embedded options as if they were separable options.

The balance of this chapter describes the evolution in the convertible product including details of their various structures, their pay-off diagrams, reasons for investing in them. This is followed by the basic characteristics of convertible securities at their various stages, their valuation parameters, and valuation models. We close by discussing aspects of trading these securities.

EVOLUTION IN THE CONVERTIBLE MARKETS

While most of the issues in the convertible market continue to be noninvestment grade rating or are unrated, it is no longer true that only firms of marginal credit quality and/or firms unable to access public debt markets raise funds by issuing convertibles. This asset class has evolved into a sizable and mature one wherein issuers have raised large amounts, exceeding $1 billion each, some even through overnight transactions with very little marketing effort.3 To understand this evolution and its future direction, it will be useful to segment this asset class into its distinct distribution channels.

Convertible Market Segments

The principal segment comprises of the publicly issued convertibles that includes those issued either as registered under the Securities Act of 1933 (“SEC registered”) or under Rule 144A institutional private placement (“144A issue”). Gross proceeds at issue in this segment are of least $50 million each. Smaller size issues—generally from “small cap” and “micro cap” issuers—may not attract institutional buying interest and as a result tend to be illiquid with wide bid/offer spreads.4 The present chapter will, therefore, focus on the publicly traded convertibles, though the economic and valuation logic apply to other convertibles as well.

Another segment of the convertible market consists of highly structured and individually negotiated transactions, wherein the issuer and a single investor or handful of investors draw up the terms and conditions of the investment and the structure of the convertible security purchased. This “private investment” is not available to investors at large. The specific one-off nonmarket features and covenants of privately placed issues may include: (a) a relatively high conversion premium in exchange for a high coupon or preferred dividend; (b) an extended period of nonconversion; (c) conversion into restricted stock which cannot immediately be monetized upon conversion; (d) a resetting of the conversion premium and/or coupon or preferred dividend based on balance sheet/income statement/cash-flow target ratios for specific time periods5; (e) debt covenant restrictions; (f) seniority in the event of bankruptcy, merger, or acquisition; and (g) provisions for voting and control issues. Typical investors are leveraged buyout funds, private equity funds, hedge funds and, occasionally, mutual funds. These buyers provide strategic capital infusion to distressed firms, firms needing added capital to restructure or grow through acquisitions, and firms not otherwise ready for, or unwilling to pursue, public market transactions. This set of investors tends to have medium or long holding period horizons, and have bullish projections about the future stock market performance of the firm and/or hedge themselves. Consequently, the lack of secondary market liquidity of the privately placed structured convertible is less of a concern.

Convertible Products Range

Convertible products6 may be divided into three categories, based on their seniority in the balance sheet and the tax treatment of the preferred dividend. These categories are (1) convertible debt products; (2) convertible preferred products of the mandatory and the nonmandatory types; (3) hybrid products which are preferred shares from a financial reporting perspective, but are structured so as to be tax deductible, and thus to reduce the net cost to the issuer; and (4) structured public convertibles.

Convertible Debt Products

Convertible Debt Products’ interest payment obligation can be in the form of cash coupons or interest accrual or both or neither. The “neither” case occurs when the value of the equity option embedded in the convertible offsets the value of coupon payments of an otherwise identical nonconvertible debt of the same issuer. Not surprisingly, the zero coupon nonaccreting structures are more common in low interest rate environments. Coupon payments and accrued interest are tax deductible and the issuer is accorded no equity credit from the rating agencies.7 The products in this category include:

• Traditional Convertible Debt: Typical maturities are five, seven, or 10 years, with a 15% to 40% conversion premium, and a nonredemption period (hard noncall) of three years or longer. The bond is issued at par, matures at par, and has a fixed conversion ratio8 and hence a fixed conversion price during its life. Basic variations include a higher conversion premium with a higher associated coupon, or a stock price trigger based conditional redemption (also known as a provisional call or a soft call protection).9 The combination of an initial period of hard noncall followed by a soft call is often used to trade off against a lower coupon and/or a higher conversion premium. As a rule, the greater the volatility of the underlying stock and the higher its growth expectations, the greater the variation from the basic structure.10 Reset or refix clauses are included when the outlooks for the firm or for the firm’s primary economic domicile country, or both, are unfavorable. The conversion price is revised downward if some stock price triggers are not met. The reset clause lowers the risk to the investor and transfers it to the issuer.11

• Zero-Coupon Convertible Debt: Also known as LYON,12 this product is a zero coupon, putable, redeemable, convertible debenture with 15 to 30 years maturity; with one day puts at accreted value at 5, 10, 15 years from the settlement date following new issuance; and with a hard noncall until the first put date. Thereafter, the issue is unconditionally redeemable at any time at the accreted value. The debenture is issued at a discount to par, calculated at the semiannually compounded yield to maturity of the security. For example, a 5% yield to maturity, 20-year LYON will be issued at a price of 37.243% of par, which is the present value of $100 discounted at 2.5% for 40 periods. The initial conversion premium ranges in most cases from 15% to 40%. The conversion ratio established at issue remains constant during the life of the security. As a result, since the bond value is accreting toward par while the conversion ratio is fixed, the conversion price rises continuously.13 Attractive features of this security from the perspective of the issuer include:

• Conservation of cash and the option to deploy it at the (presumably higher) internal rate of return of the issuer;

• Tax deduction on the accrued interest;

• Upon conversion, the per bond equity addition to the balance sheet is comprised of the initial issue price plus the accrued interest amount;

• Upon conversion, there is no re-capture (by the Treasury) of the accrued tax deduction;

• The LYON and its zero coupon variation of the CoCo structure (discussed later) are, all else being equal, the most debtlike of all equity-linked securities with the highest effective conversion price;

• This structure signals to the market that the issuer is unwilling to sell equity at the spot price at issue but only at the high effective conversion price.

The trade-offs to investors for the rising conversion price include the higher option value in the five years of hard noncall; a higher accretion rate; and the option to put the security back to the issuer at accreted value at the stated intervals.14 Among the typical variations in the structure are higher conversion premiums for highly rated issuers and/or high volatility–high expected growth stocks, sometimes in conjunction with a first put in year 3 with a corresponding hard noncall also for 3 years. Other variations include longer first put date, often in year 7, as well as nonsym-metric put and call dates with the first call date occurring before the first put date.

• Original Issue Discount Convertible Debt: This structure (called the OID convert) combines aspects of the preceding two structures in that a small part of the yield to maturity is paid in the form of cash coupon, and the balance accretes. As is to be expected, all else being equal, the yield to maturity in this structure straddles those of the preceding two structures. The conversion price is also rising but at a rate lower than that for the zero coupon structure. Maturity for this product is usually five to seven years with a typical hard noncall protection of three years and is typically not putable prior to maturity although there is no reason why it cannot be structured with, say, a put in year 3 and final maturity in year 5 or 7.

• Premium Redemption Convertible Debt: This is simply another variation of the OID convert. The only difference between this variation and the OID is that the latter is issued at below par and accretes to par at maturity, while the Premium Redemption Convertible is issued at par and accretes in exactly the same manner to a number above par and hence the name. This structure occurs more in Europe and Asia, where regulations may require the issuance of bonds at par.

• Step-Up Convertible Debt: This product follows a pay-in-kind or PIK structure common in the non-investment-grade debt market, wherein the security pays no coupon for a period of up to five years. The coupon then steps up to a higher level cash coupon than what it would have been if it were current coupon paying from the start. Adapted for the convertible market, this security pays a low cash coupon for the first three years, which is also the hard noncall period. The coupon then steps up for the balance of the life of the convert that ranges from another four to seven years. The effective conversion price rises continuously until the last low-coupon payment date, and stays constant at its higher level thereafter until maturity. As might be expected, the absolute levels of the coupons in step-up convertibles are much lower than those in the high-yield market due to the inclusion of the conversion option. Interest is expensed at the rate of the yield to maturity, which is higher than the cash coupon during the low coupon period, but lower than the cash coupon rate in the later period. The incentive for the issuer to redeem this security prior to the higher coupon kicking in is therefore very strong. A flip-side variation of the structure, particularly in low interest rate environments, is the step-down convertible wherein after an initial cash coupon period the coupon drops to a lower level or to zero with or without accretion.

Contingent Convertible Bonds

In most convertibles the investor has an American option to convert into the underlying stock. As a result, Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP) require that the denominator in the earnings per share (eps) calculation add the new number of shares to be issued upon conversion of this convertible to the existing number of shares outstanding. The increase in the number of shares in the denominator—and hence eps dilution—occurs immediately upon the settlement of the newly issued convertible transaction and is based on the conservative assumption of immediate conversion by the investor. In this nicknamed CoCo convertible, the conversion option granted investors is not immediate but contingent upon the stock price exceeding a prespecified hurdle, i.e., the investor’s option to convert “knocks in.” By adopting this twist, first introduced in 1999, the issuer did not have to recognize immediate eps dilution but could defer it to the knock-in date. Under those rules, the CoCo structure grew to dominate U.S. convertible new issuance. The majority of the issues were investment grade, and the transactions generally very large, as the non-immediate dilution feature was particularly attractive to issuers.

However, that was before the Financial Accounting Standards Board’s Staff Position APB 14-1 in May 2008 and adopted shortly thereafter. It established that prospectively as well as retroactively, all convertible debt would be treated under the “bifurcation concept,” i.e., viewed as a combination of straight debt plus an equity component. Consequently, regardless of the CoCo structure, eps dilution would be recognized immediately upon issuance of the convertible security. As a result, the issuance of CoCo convertibles has declined materially from its peak. CoCos now may, at the option of the issuer, settle in shares, i.e., physical shares settlement, or a combination wherein the par value may be paid in cash and the in-the-money component paid in shares, called net share settlement, or both components paid in cash. Clearly, the latter two alternatives are aimed at reducing the number of shares delivered upon conversion.15,16,17

• Contingent Payable Bonds: As one might surmise from the name, these CoPay bonds knock-in contingent payment by the issuer to the investor subject to the stock price exceeding a pre-established threshold. The Co-Pay feature generally helps defer voluntary conversion by the investor thereby allowing the issuer to continue claiming interest deduction on a typical long-dated structure since the bifurcation method also applies here. Conditioned on a credible probability of the contingent payment, the issuer can deduct interest expense at the long term straight debt rate matching the maturity of the security. The magnitude of the tax benefits of this structure varies depending on whether the security is ultimately converted or not, but in either case it potentially generates significant tax benefits to the issuer. The Co-Pay structure may also be embedded inside CoCo or any of the accreting structures.

• Negative Yield Convertible Debt: Yield on the benchmark 10-year Yen denominated Japanese government debt has hovered below 1% for several years and was at 0.54% as of 3/10/11 for five-year Japanese government bonds (JGBs). Dividend yields on Japanese equity are traditionally very low. Under this scenario, consider a yen denominated, zero coupon, low conversion premium, unsubordinated convertible debt with an effective maturity of five years issued with hard noncall also of five years. Its theoretical value would most likely be a few points above par. To make it equitable to both issuer and investor, such a convert might be issued at 1% to 3% above par, yet it matures at par thereby resulting in a negative yield to maturity security. Not surprisingly, this structure will be more frequently used in a low interest-rate environment and particularly so when combined with high volatility in the underlying stock.

Increasingly, convertibles debentures have been issued as senior unsubordinated debt, pari passu with senior existing or future nonconvertible debt of the issuer. This feature has long been common in convertible bonds issued out of Europe and is particularly suited for CoCo/CoPay structures. The collateral benefits accruing from of this structure are the increased liquidity due to it facilitating capital structure arbitrage trading as well as credit hedging via CDSs in addition to a higher tax deduction rate.

Convertible Preferred Products

Convertible preferred products are senior only to the issuer’s common stock. The preferred dividend is not tax deductible, and hence is a costly source of funding on an eps basis. Convertible preferreds are mostly issued, therefore, when the firm needs equity credit from the rating agencies, or when it is unable or unwilling to issue debt due to leverage covenants imposed on them by other classes of senior securities, or when the firm does not pay taxes due to accumulated losses or a combination of these reasons. These products are viewed as “permanent” or long-term financing and provide the issuer with the option to skip payment of preferred dividends without triggering default. Hence they are generally accorded up to 50% equity credit from the rating agencies.18,19 Withholding taxes and the low bond floor equivalent resulting from the perpetual maturity are the primary reasons why these structures are not commonly issued in Europe. Withholding tax on preferred dividends applicable to non-U.S. investors deters them from investing in U.S. preferreds too. The products in this category may be further subdivided into those that redeem at par if not converted, that is, without impairment to the original investment, and those that convert mandatorily into a formula number of common shares at maturity. In the latter case, investors may lose part of their initial investment if the stock price falls below that on the date of issue.

Nonmandatorily convertible preferred shares include:

• Perpetual Maturity Convertible Preferred Shares: This is the preferred share counterpart of the Traditional Convertible Debt described above in that it has a fixed conversion price, it is a very easy structure to understand, and has been a staple of the convertible market for several decades. The main differences are its perpetual maturity and lower seniority. Consequently, the dividend on the convertible preferred will be higher than the coupon on an otherwise identical convertible debt. The higher rate on the preferred results from the fact that both the corresponding benchmark interest rate and the credit-spread corresponding to this longer maturity are higher, and the two together form the base rate.20 The dividend rate on the convertible preferred is determined by adjusting downward from this higher base rate for the embedded equity option.21,22

• Dated Convertible Preferred: Again a convertible adaptation from the high-yield market, this product has a maturity of 10 to 12 years, although 30-year dated convertibles have also been issued. Typically, it matches or is outside the maturity of high-yield debt which is usually 10 and sometimes 12 years. If not converted, a dated convertible preferred must be redeemed at par at maturity. In all other aspects it is similar to the perpetual maturity convertible preferred. Rating agencies are less likely to accord any equity credit due to this product’s debtlike redemption at maturity feature and is almost always used by noninvestment grade issuers faced with covenant restriction limits.

• Step-Up Convertible Preferred: This product is analogous to the step-up convertible debt, but with perpetual maturity.

Mandatorily convertible preferred shares in essence transfer the downside risk of the stock to the investor in exchange for a higher preferred dividend. This category of converts includes:

• Capped Common: Also known as PERCS,23 the capped common is essentially a combination of purchasing a common share and writing an out-of-the-money call to the issuer. Investors have no conversion option at any time during the life of the security, which is typically three years and sometimes shorter. The issuer, however, may redeem this convertible at any time provided the preferred dividend due until the maturity date is paid in its entirety. The premium for the call option that the investor is short is packaged in the form of quarterly preferred dividends. This packaging of a common options strategy, known as the buy-write strategy, allows convertible funds to invest in them. Were these three-year convertible securities unbundled, the charter of convertible funds which may disallow pure play option positions would generally prohibit such investment. The investor in the capped common realizes all of the stock price appreciation from the spot price at issue up to the cap or strike price level; anything beyond the cap price is retained by the issuer. On the other hand, the investor loses part of her principal to the extent that the stock price at maturity is lower than the price at issue. In a rising equity market, the issuer has almost always exercised the call option and this product has under-performed the common stock from an investor perspective. Consequently, its popularity has declined considerably. Rating agencies may generally be expected to accord equity credit of up to 85%.

• Modified Capped Common: A variation on the above, the modified capped common may be viewed as a PERC with some downside protection to the investor, in the form of an embedded put the investor purchases from the issuer. Microsoft Corporation was the first to use this structure in 1996; it offered $1 billion of this security with a cap of 28% on the upside, but without any downside risk to the investor; that is, with no hit to the principal. The embedded put purchased by the investor for this three-year maturity security was an at-the-money European put on what was then a high volatility stock, and hence was very expensive. The net option premium paid to the investor in the form of preferred dividend was accordingly low.24

• Mandatorily Convertible Preferred: This structure, invented in 1993, and its hybrid version, the Trust Mandatory Preferred (described below) have been so frequently used to raise funds in the convertible market that it has spawned a host of acronyms.25 Typically, it is issued at the same price as the underlying stock price; matures in three to five years, most frequently three-year maturity. It has a conversion premium in the 20% to 22% range, but may be higher in low interest rate regimes. It is easiest to view this security (popularly known as a mandatory) as a traditional convertible with a three-year maturity that is share settled, packaged with an embedded at-the-money put purchased by the issuer from the investor. The number of shares received by the investor at maturity depends on the share price on the maturity date.26 This security’s popularity has stemmed from the high equity credit from rating agencies, the transfer of risk to the investor in the event of a decline in the share price, and the traditional convertible features on the upside. Because the issue is settled in shares, the question of credit risk of the issuer with respect to payment of par is irrelevant. Only the credit risk with respect to the payment of the preferred dividends remains. Consequently, the structure is relatively insensitive to the creditworthiness of the issuer. The typical high preferred dividend rate of the mandatory being attractive to the buyers is another reason for its popularity.

• A variation on the preceding structure, the modified mandatory convertible preferred provides the investor with downside protection for the first 10% to 25% from the spot price, in exchange for a lower preferred dividend. In effect, the net put component of the package purchased by the issuer is 10% to 25% out-of-the-money. Hence the put premium is lower, and this is translated as a lower preferred dividend. The maximum number of shares is 1.111 for a 10% out-of-the-money put case, rather than the one share in the at-the-money put case of the traditional mandatory. The equity credit accorded is identical.

Mandatorily and modified mandatorily exchangeable securities (wherein the underlying stock is different from the issuer’s common stock) can be issued as debt securities whereas a mandatorily convertible security issued on the issuer’s own stock is deemed as a forward sale of the common and hence is not tax deductible. Specialized structures, the specific details of which are outside the scope of this chapter, are crafted in compliance with the applicable tax code in order to achieve effective tax deductibility. The next subsection briefly outlines these hybrid products.

Hybrid Convertible Products

This category consists of structures which are treated as preferred shares for financial reporting purposes, but their distributions are tax deductible. The development of hybrid convertible preferreds closely followed the invention of the MIPS, QUIPS and TOPRS27 in the fixed-rate nonconvertible preferred market. The essential structure in this category is as follows: a Trust28 issues convertible preferred shares to investors and simultaneously uses the proceeds to purchase convertible subordinated debt from the issuer. The convertible subordinated debt will be the sole asset of the Trust. The coupon from the issuer to the Trust exactly mirrors the preferred dividend paid by the Trust. Upon conversion by the investors, the Trust in turn converts the convertible debentures and passes through the shares to the investors.

• Trust nonmandatory preferred: The maturity of this product ranges from 15 to 30 years and equals the life of the Trust; its cash distributions and maturity mirrors that of the convertible debenture purchased by the Trust from the issuer. Investors are generally not sensitive to the structural difference between these securities and the traditional perpetual convertible preferred. Rating agency equity credit may be equal to that of the traditional perpetual convertible preferred, although recent discussions might lead this product to be viewed as being closer to debt.

• Trust mandatory preferred and modified mandatory preferred: This product is similar to its non-tax-deductible counterpart, except for the complexities involved with the Trust and the forward purchase contract between the investor and the issuer which is required to ensure mandatory conversion at the end of the life of the Trust, typically three years. Variations among the trust mandatory preferred relate to the structure and conditions regarding the forward purchase contract. Trust structure is also employed when the entity selling the shares is not an SEC registrant, but rather an individual or an investment or venture capital partnership. If the creditworthiness of the corporate issuer is less than acceptable, or the seller is not an SEC registrant, preferred dividends due the investors over the life of the security are escrowed in the Trust in the form of Treasury strips with maturities matching the scheduled preferred dividend payment dates. On the date of issue, proceeds from the sale of the Trust mandatory preferred to the investors, less the cost of the Treasury strips and Trust administration costs are forwarded to the issuer. The underlying shares are simultaneously escrowed in the Trust so as to create a bankruptcy remote Trust with an implied AAA credit rating.

Zero Premium Exchangeable Debt

This product acronym “PHONES”29 is a 30-year zero conversion premium security issued at the same price as the underlying share into which it is exchangeable. It is redeemable by the issuer at any time, and convertible by the investor at any time, though there may be an initial nonconversion period. However, if the security were to be converted by the investor in the initial 30-year maturity period, the conversion ratio will be 0.95 implying a 5% penalty for voluntary conversion. The security is extendible for a further 30 years, subject to certain minimal conditions, at which time the conversion ratio becomes one share. The investor receives a pass-through of the dividend paid by the underlying share plus a fixed interest component. Any increase in the dividend paid by the share is deemed return of principal and deducted from the residual “par value” which is initially equal to the original issue price. Investors are liable for taxes on income deemed as received at the issuer’s subordinated straight debt rate, which considerably exceeds the interest paid by the issuer. In exchange, the investor’s basis for the share will rise with time. Zero premium exchangeable debt, at its most basic level, is a tax advantaged way for the issuer to monetize its holding of the underlying shares without actually transferring ownership of the shares. It thus potentially allows the issuer to defer the capital gains tax for as long as 60 years while enjoying a much larger interest deduction than cash coupon paid (6% imputed rate versus 1.75% actual cash coupon rate in one instance). Given the substantial tax advantage it provides the issuer it is attractive for the issuer. However, due to its material tax liability for a taxable investment entity, this product is most likely to appeal to tax sheltered investment vehicles of the equity income type, tax sheltered index funds, and offshore hedge funds. Many investors do not consider this security to be a convertible, as it lacks any meaningful convexity and their popularity has fallen off.

Structured Public Convertibles

A recent innovation to reduce earnings per share dilution relating to the issuance of a convertible entails combining it with an equity derivative overlay transaction. The most common among these is the “call spread overlay.” Consider a convertible issued with a 25% conversion premium. With part of the proceeds from the sale of this convertible the issuer buys from an investment bank an off-setting 25% out-of-the-money call matching exactly the conversion option embedded in the convertible in its maturity, number of shares and redemption features. Further, the issuer sells a 50% out-of-the-money call with identical features. In so doing, the issuer has reduced the potential dilution impact of the convertible through this net 50% out-of-the-money call. In addition, the net cost of the call spread can be deducted for tax purposes. Furthermore, the investment bank, as the seller of the call spread, has to hedge itself—in the 25% to 50% out-of-the-money range—by buying the underlying shares, thereby benefitting the stock. At maturity settlement for the investor in the convertible is as usual and can be in shares or cash or combination. If the stock exceeds the 50% threshold, the settlement with the investment bank is in net shares.

Exhibit 42–1 provides a schematic of the terminal payoff diagrams for the major convertible securities. Similar payoff diagrams can be drawn for the other convertible products.

EXHIBIT 42–1

Equity-Linked Payoff Diagram

Since the upheaval in the convertible market in 2005, and even more dramatically in 2007–2008, issuers and investors have moved noticeably to the simpler product structures. Traditional convertible bonds, mandatories, and convertible preferred shares have been chosen over some of the more complicated structures described above.

Investing in Convertible Securities

The most frequently cited reason to invest in convertibles is that convertibles provide upside participation with downside protection. While generally true, it does not fully apply to mandatory securities in which the investor retains the downside risk of the stock. Since convertibles span the space between equities and straight debt, the risk profile of each convertible product contains elements of both. Investors will choose from the subset of convertible offerings that match their target risk-reward profile and/or their assessments of the future levels of the underlying stock price, interest rate and credit-spread levels, volatility parameters, as well as market technicals such as supply/demand and liquidity. These are discussed in detail in the following.

Institutional investors in convertible securities can be broadly classified into outright investors and hedgers. Outright investors include the dedicated convertible funds, equity income funds, insurance companies, and fixed income funds seeking to participate in the potential upside in the equity. Convertible mutual funds, money managers who manage third party funds such as those from pension funds with specific allocation for convertibles as an asset class, as well as in-house managed funds earmarked for convertibles are also included in this category. The main hedge funds participants include those focused on convertible arbitrage, equity volatility arbitrage, and capital structure arbitrage. The common investment objective of the outright investors is to obtain equity exposure with portfolio volatility lower than that of common stocks. They are active money managers and are often measured by holding period returns compared to benchmark indexes such as the Standard & Poor’s 500 Index, or the Russell 2000 Index of small stocks, or a risk adjusted benchmark. A subset of managers is measured by the Sharpe ratio.30 An aspect of the charter of outright convertible funds is that they may not be allowed to hold the common shares received upon conversion nor permitted to hedge their convertible positions. That flexibility is left to the convertible arbitrage funds.

The assets under management dedicated to convertibles, particularly by hedge funds, in the past decade has dramatically altered not only the size of this asset class, but also the way convertibles structured, marketed, evaluated, and traded. Convertible hedge funds went from being a significant part of convertible market to being the most dominant segment leading up to 2007 when they were variously rumored to be more than 80% of the funds invested in U.S. and global convertible markets. Further, due to their high portfolio turnover, they accounted for the majority of the liquidity provided. The financial illiquidity of 2007–2008 hit dedicated convertible arbitrage funds very hard forcing many to shut down while multistrategy hedge funds drastically reduced their allocation to the strategy. As they ceased to be the buyers to drive the new issue pricing, outright buyers with a longer holding period horizon have seen new issue pricing move in their direction and now account for a larger segment for the asset class than before the illiquidity event.

Outright investors will seldom buy a convert unless they like the fundamentals, or the equity story, of the underlying stock. Ideal attributes of an issuer, from outright investors’ perspective, include

• A strong management team with a well articulated business model

• Presence in a growing sector of the economy

• The firm being in the growth phase of its business cycle

• Strong or improving credit with the ability to undertake the fixed liability without jeopardizing its credit rating

• Credit-spread established by an actively traded nonconvertible bond by the issuer or indications of credit default swap or asset swap levels

• High volatility stock

• Little or no dividend on the common stock

• Liquid secondary market for the convertible and the underlying stock

Additional items considered by hedge funds, who are essentially relative value investors, include:

• Cost to borrow the stock

• Richness or cheapness of the implied volatility of the options embedded in the convertible versus those of comparable listed equity options and the historical volatility of the underlying stock. This forms the basis of volatility trading.

• Implied equity volatility of credit default swaps and equity default swaps. Together with implied volatility of comparable equity options.

• Credit-spreads for all levels of seniority of obligations of the underlying stock, including the convertible with a view to capital structure arbitrage. The idea is to arbitrage (a) credit-spread mispricings, (b) differential implied probabilities of corporate default, or (c) recovery rate in the event of default embedded in the pricing of these obligations.

Thus, evaluating a convertible encompasses, among others, fundamental equity research, analysis of interest rates, credit-spreads, capital structure, associated equity and debt derivatives as instruments of trade expression or hedging, market technicals, liquidity of the security itself as well as the restriction on, and costs of, shorting the underlying stock. To understand the arena where this increasingly sophisticated analysis is deployed, we discuss convertible new issues next.

Convertible New Issues

Publicly issued convertible new issue product in the United States has had its ups and downs as it grew steadily in size from $12 billion in 1992 to over $106 billion in 2001 before the collapse of the dot.com boom and did not recover to the $100 billion level until 2007. And, not surprisingly, it dropped off again following the global illiquidity crunch that followed, ending with a paltry new supply of $39 billion in 2010. Taking the maturing issues into consideration, there was indeed a net contraction of the market during these years. Globally, the new issuance peaks and valleys roughly mirrored the United States’ pattern with total issuance of $180 billion in 2003, $198 billion in 2007, and ending with $101 billion in 2010. While geographically continuing to be the most liquid of the convertible markets with the largest new issue calendar, the United States’ proportion of the global new issues has fluctuated from as high as 61% in the challenged market conditions of 2008 to as low as 38% in both 2009 and 2010, but accounted for more than half of global issuance for most years in the last two decades. European issuance, on the other hand, has been steady at mid-teen to mid-twenties percent, with a spike to 37% in 2009. Japanese issuance in the current century ranges in the mid-single-digits to a rare spike of 16% in 2004—due to a few large transactions including one by Toshiba Corp for Yen 100 billion (US$923 million)—and considerably below the levels of issuance commensurate with its prior decades of growth. However, as might be expected, the portion of non-Japan Asia new issuance—at 25% in 2010—is considerably higher in keeping with their very high rates of growth compared to those of the developed regions comprising the United States, Western Europe, and Japan.

What determines the amount and type of convertible financing selected by issuers? One key factor, surely, is the economic cycle, along with the equity and bond market environments. As might be expected, in the low interest environments, issuers will clearly prefer to build up their capital base/extend maturities/restructure their balance sheets by issuing straight debt rather than dilute their earnings by issuing equity or equity-linked securities. Banks and financial companies, particularly, and others that bore a major brunt of the downturn were the exceptions with mandatories being the structures of choice for them. Hence the structure of convertible financing has a cyclical element to it with tax and accounting rules as factors being not far behind. Governmental financial inputs to stabilize global economies and the resultant or concurrent low interest rate environment are expected to curtail convertible new issuance until the economies are in stronger recovery stages. History provides an indication of the choice of structures.31

Despite the lull in convertible new issues since the 2007–2008 financial crisis years, 15 converts were issued in the United States with proceeds exceeding $1 billion each, from 2009 on to the first quarter of 2011. Select examples are: (a) 4.75% mandatory maturing on December 1, 2013, issued by General Motors on November 18, 2010, as it emerged from bankruptcy; (b) Citigroup’s 7.5% mandatory maturing on December 15, 2012 and issued on December 6, 2009 for $3.5 billion to add equity to its capital base; (c) Intel Corp.’s 3.25% convertible bond maturing on August 1, 2039 and issued on July 21, 2009 for $2.0 billion; and (d) MetLife Inc.’s $3.0 billion mandatory issued on March 3, 2011 and maturing on September 11, 2013, carries a preferred dividend of 5.0%. Depending on market conditions, the average size of a U.S. convertible issue has ranged from a low of $160 million to a very respectable and liquid $550 million. European issues are roughly comparable in size, although with larger variations from year to year, while non-Japan Asia issues are gradually increasing in size to an average of $225 million in 2010. While Japanese issues are predominantly Yen denominated and European issues in Euro, even in these countries US$ denominated issuance is not uncommon and is the currency of choice in most non-Japan Asian issuance.

When US 144A transactions started being issued with increasing frequency, they were not kindly received, as many tended to be overnight issues as opposed to being registered and fully marketed over a few days or weeks of road shows.32 That is, the issues are announced after the trading day is over, orders solicited that same night or early the next morning, and the transaction completed before trading starts that morning. Over time, the ire over 144A issuance has tempered as investors have come to accept their inevitability. The demand for the product is largely unaffected while issuers do not need to provide investors a number of days, as is done in registered offerings, to study the details of the company’s finances and/or the transactions prospectus thanks to a large extent to hedge funds, institutional buyers and QIB’s as they can quickly respond to the new issue offer.

Although the total issuance volume in this asset class pales in comparison to both investment grade and high-yield issuance in the United States, they are still healthy. And in countries and regions in which the straight debt market is not as developed, convertibles are the vehicles of choice as the economies graduate from bank financing. That said, we next discuss convertible valuation.

BASIC CHARACTERISTICS OF CONVERTIBLE SECURITIES

The simplest convertible security, namely a traditional convertible bond, can be viewed from a fixed income investor’s perspective as a combination of an otherwise identical nonconvertible bond plus a call option to exchange the bond for the underlying shares. From the equity oriented investor’s viewpoint, it may be viewed as a combination of a long position in the underlying shares, a put option to exchange the underlying shares for an otherwise identical nonconvertible bond, and a swap to receive coupons of the convertible bond in exchange for dividends on the underlying shares. This is an immediate implication of the European version of the put-call parity theorem.33 The introduction of redemption features and other embedded options in the more varied convertible structures discussed above may complicate, but does not invalidate, the basic equivalence concept.

Value Diagram and Descriptive Measures

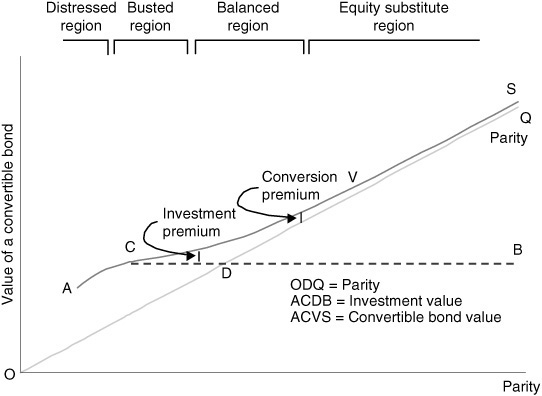

Exhibit 42–2 value diagram shows the roles of debt and equity components in valuing a convertible security. The horizontal axis is the value of the underlying shares and equals the stock price times the conversion ratio. This value is called the convertible’s parity value, or simply parity. The line ODQ also represents parity. ACDB is the value of the corresponding straight debt, and ACVS represents the value of the convertible bond. Because a convertible bond provides the investor with rights beyond those provided by an otherwise identical nonconvertible bond, in that it can be converted into the underlying shares, its value should equal or exceed the larger of the corresponding debt or parity. Accordingly, in the value diagram, ACVS is equal to or above the segment OD, where bond value exceeds parity, and is equal to or above DQ, where parity exceeds bond value.34

EXHIBIT 42–2

Convertible Value Diagram

Three measures of premium are commonly used in convertible parlance. They are the conversion premium, the points premium, and the investment premium. The vertical distance between ACVS denoting the value of the convertible bond, and the bond floor (or investment value) line ACDB, represents the convertible bond value in excess of its investment value. This is expressed as the investment premium, defined as

![]()

The vertical distance between the convertible bond value ACVS and parity ODQ represents premium over parity. This may be stated in points premium, defined as the dollar value of the convertible bond minus the dollar value of parity, expressed as a percent of par. For example, if the bond price were $1047.50 and parity were $920, then points premium would be 12.75 points. Alternately, the premium may be stated as the conversion premium, defined as

![]()

The conversion premium is 13.86% in the illustration above. Conversion premium, or simply, the premium, is an important and commonly used measure. Together with the investment premium and the notion of the delta of the convertible (defined below), the conversion premium helps characterize the change in the value of the convertible with a changing underlying share price.

The ratio of the change in the value of the convertible to the change in the value of the underlying shares, or parity, is called the convertible’s parity delta. As does the equity call option delta, the parity delta ranges from zero to 1.0, and is the per share delta of the convertible. Therefore, it is also called the delta, or the neutral hedge ratio; the per share basis is the unstated assumption. At zero delta the convertible behaves like straight debt, and at 1.0 it behaves like common stock. Therefore, the delta of the convert may be viewed as the correlation of the change in the price of the convert to the price change in the underlying share. A 65% delta means that for small moves in the underlying share price of, say, $0.10, the change in parity = the change in the price per share times the number of shares per convertible = $0.10 × 6.621 = $0.6621. The expected change in the value of the convertible bond then is = the change in parity times the hedge ratio = $0.6621 × 0.65 = $0.4304, or 0.0434 bond points. If an investor of the convert wanted to hedge the equity risk, she would in theory have to sell short.

Conversion ratio × delta = 6.621 × 0.65 = 4.3037 shares per bond to establish a delta neutral position.

The neutral hedge ratio is the tangent to, and the slope of, the convertible bond valuation curve at a particular stock price. For infinitesimal moves up or down in the stock price from this initial level, a hedged portfolio consisting of long the convert and short the shares, as illustrated above, will result in neither a loss nor gain. For noninfinitesimal stock price change upwards, the gain arising from the long position in the convert will be lesser than the loss incurred due to the short position in the shares as the conversion premium declines.35 In the event of a large move up, the ex-ante neutral hedged position turns out to be ex-post underhedged, and hence the loss. The reverse is true in a large down move in share price. In this case, decline in the convert price, all else being the same, will be lower than the gain on the short position in the shares as the conversion premium increases or “blows out”. Viewed ex-post, the position was over-hedged. The main point to note is that a traditional convert is long an embedded equity call option and thus is a positive gamma security with respect to the underlying stock. On the other hand, like all callable fixed income instruments, it is also negatively convex with respect to interest rates.

Stages of a Convertible Security

The price response of a convertible to a change in parity can be conceptually segmented into four stages or regions. These approximate regions are delineated in Exhibit 42–2. They are:

Balanced Converts

Several factors determine the conversion premium of a convert. Among the more important of these is the price response of a convert to changes in the underlying stock price and interest rates. Convertibles with conversion premium of 15% to 40%, and investment premium of 15% to 25%, respond materially to both. Their deltas range from roughly 55% to 75%.36 Hence converts with these attributes, either upon issuance or subsequently as a result of stock price movements, are called balanced convertibles. Their upside/downside participation and risk/return tradeoff characteristics appeal to outright convertible funds and equity funds seeking a lower risk alternative or add-on position to common stock from an issuer with attractive equity fundamentals. All else being equal, lower the premium, more attractive the convertible from a buyer’s perspective.

Equity Substitute Converts

The more the underlying stock price exceeds the fixed conversion price of a traditional convert, or, in the case of an accreting convert, the then effective conversion price, the deeper in-the-money is the convert. When such a convert’s premium is about 15% or less, while its investment premium is higher than 40% it is referred to as being equity like, or as an equity substitute. It will respond sharply to changes in parity, and to a lesser extent to changes in the interest rates or interest spreads, and its delta is usually above 80% to 85%. Clearly, this movement is due to the investor put option to exchange the convert for its redemption price being now deep-out-of-the-money. While share price is the prime determinant of the value of a convert in this phase, it cannot be emphasized enough that other factors, such as remaining call protection and stock price volatility, also materially affect its value. The shorter (longer) the remaining call protection, the lower (higher) the conversion premium an investor would be willing to pay. Outright convert funds tend to sell the security at this stage in favor of other balanced converts while equity income funds tend to buy in this stage. Hedge funds’ trading role increases along with stock price fluctuations, in what is known as gamma trading. With positive convexity feature of the convertible prominent at this stage, portfolio leverage and small net capital requirement due to the high delta, this stage of the convertible constitutes a potentially lucrative trading opportunity for hedge funds.

Busted Converts

If the share price were to decline such that the conversion option were deep-out-of-the-money, and correspondingly, the put option deep-in-the-money, the conversion premium would increase while the investment premium would decline. The conversion premium in this stage is usually larger than 50% and may be as high as 200% or even higher, but investment premium is less than 15%. As the conversion option is worth very little, the convertible bond value approaches that of an otherwise equivalent nonconvertible bond. Its price falls to a level determined by the relevant yield measures. For traditional converts, those measures are the current yield and the yield to maturity. For the accreting converts they are the yield to put and/or yield to maturity. Outright convert funds exit their positions in these converts, to be replaced by fixed income funds seeking equity participation and hedge funds with credit analysis expertise. Credit risk may be offset by buying CDSs if they are available. In the absence of CDS on the particular issuer, proxy credit hedging methods include purchasing CDS of a similar credit in the same industry sector, shorting straight bonds of the issuer particularly if they are pari passu in seniority at a duration based hedge ratio, or buying equity puts or over-hedging by shorting more shares than suggested by the bond’s equity delta. Some funds, though, may choose to retain exposure to the credit if their fundamental credit analysis or analytical models conclude that the risk/reward ratio is compelling, the yield give-up in exchange for the deep-out-of-the-money conversion option is relatively minor and, sometimes may even be negative, due to market inefficiencies in this region. However, fixed income funds that traditionally invest in senior or senior-subordinated bonds may not be reluctant to buy subordinated convertibles, nor do they generally buy busted convertible preferreds.

Distressed Converts

These converts may be considered a subset of the busted converts with the distinction that the stock price has fallen so far as to materially increase the probability of default. The ratings may be lowered either explicitly by the rating agencies or implicitly by the market as reflected in a substantial widening of its credit-spread or materially increased CDS premiums. Unlike the other stages in which the bond floor holds up reasonably well (see Exhibit 42–2) here the bond floor falls rapidly with the stock price. At this stage, the fixed income funds exit and distress funds or vulture funds, are the primary investors. These funds specialize in assessing the default probability and recovery rate estimation in the event of default. Both the conversion premium and the investment premium are very small to negligible in this stage. Interestingly, the gamma with respect to the stock price is extremely high as small changes in the low stock price may change the delta very significantly. Distressed funds may be long or short the convertibles based on the relative values of other senior or pari passu debt used as hedging instruments as well as depending on the availability and relative attractiveness of establishing deep-out-of-the-money protective put hedges.

Before leaving this section, some caveats are in order. First, the stages discussed do not have discrete boundaries. For instance, newly issued converts in Europe may have high conversion premiums but a low investment premium, and a delta in the region of 55% to 70%. This is due to the very high implied ratings of the investment grade converts resulting in a high bond floor. Second, convertible securities are not static, in that their price response changes and they may become more equity-like or debtlike with the attendant changes in the risk/return profile. Consequently, analytical tools for fundamental equity research as well as those for valuing fixed income securities and derivatives would be needed to select and manage a portfolio of convertible securities. Third, while the conversion premium is often used as a readily available measure to determine the current stage of the convertible, that is, whether it is a busted convert or in-the-money or something else, the more appropriate measure is the investment premium. For example, an in-the-money convert with extended period of remaining call protection, on a volatile, low dividend paying underlying stock can trade at substantial conversion premium. However, higher (lower) the investment premium, unambiguously more (less) in-the-money is the convert.

APPROACHES TO VALUATION OF CONVERTIBLES

In this segment, we discuss the traditional valuation method as well as the analytical—and more mathematically intensive modeling—approaches. The latter are increasingly more standard though it is not uncommon for investors to use both these approaches, to varying degrees to supplement each other.

Traditional Valuation Method

This approach is based on the premise that buying a convertible is the equivalent of buying common stock at a premium with the premium recouped over time from the difference between the higher income from the convertible coupon and the lower dividend on the underlying stock.37 Payback period or break-even period is the principal metric employed in assessing the relative attractiveness of the convert versus the common stock. The shorter the payback period, the more attractive the convertible, especially if the payback period is shorter than the call protection period. As we shall see, the concept of payback period is flawed, yet this concept continues to be used by some equity-oriented investors as an adjunct to their fundamental analysis of the underlying stock. Unfortunately, this measure is not applicable to some of the newer structures, and may even prove misleading. Even within the traditional structures, most convertible new issues in the past decade would fail the payback period test. We will use the following example to explain the traditional valuation method.

Consider a convertible bond issued at a par of $1,000 by PQR Corp. with 2.625% annual coupon and a five-year maturity that can be converted into 16.1421 shares of PQR common stock. Due to the appreciation of the stock price since its issue and the elapse of time—it now has about four years remaining to maturity—the bond currently trades at 121 (bond points, in percent of the par amount) and the common stock at $65.06. The common stock dividend has been, and is still, zero.

If an investor purchased one PQR convertible at 121 instead of buying the common shares equal to the conversion ratio of the note, she paid a premium of $159.75 (= $1,000 × 121 percent – $65.06 × 16.1421), or 15.975 bond points. However, this premium would be compensated for by the cash-flow differential between the convertible bond and the underlying shares:

Annual cash-flow differential

= Par amount × coupon rate − Parity × dividend yield

= $1,000 × 2.625% − $1,050.25 × 0%

= $26.25

This implies that each year, the bond investor receives $26.25 more income than she would from dividends on the PQR common shares. Thus the payback period is:

= Premium paid/Annual cash-flow differential

= $159.75 / 26.25

= 6.09 years.

Simple derivation leads to the following formula for computing the cash-flow payback:38

![]()

where current yield refers to the current yield of the convertible. For the convertible the conversion premium was 15.211% and the current yield is 2.625%/121 = 2.169%, and the dividend yield on the common was zero. Using these inputs, Equation (42.3) results in the same payback period of 6.09 years. All inputs for the computation should be in decimals.

An alternate method of calculating payback period, though less defensible, is more commonly used. It is called the dollar-for-dollar payback. Under this method, the implicit question asked is, “If I were to invest the same dollar amount in buying the common shares as I would in buying the convertible, what would be the payback period of the premium?”

In the above example, if the same dollar amount were invested in PQR stock, one could buy $1,210/$65.06 = 18.5982 shares. The annual cash-flow differential would still be the same as before, as would the payback period under this method, on account of the fact that PQR pays no dividends. However, if the stock paid a significant dividend, the latter method would result in a longer payback period. The formula for this latter method can be derived as:

![]()

The denominator of Equation (42.4) is called the yield advantage. Note that the payback period of over six years is longer than the remaining maturity of the PQR convertible bond, which is about four years. Is this a valuation anomaly, or is the valuation approach lacking?

While the definitions of paybacks can be refined by using dividend growth rates and discounting the cash-flow streams, the basic flaw in the traditional valuation approach lies in its failure to consider the optionality embedded in the convert, i.e., in its assuming conversion into common stock with absolute certainty. In the case of the traditional convertible, bond investors have the right, but not the obligation, to convert should the stock price not exceed the conversion price, in which event they would receive par at maturity. And the meaning of payback period becomes even more problematic for accreting securities. For example, investors in zero-coupon convertible bonds do not receive current cash income. Thus, the convertible’s income advantage would be zero or negative, and it’s payback period could not be calculated. One may be tempted to substitute the yield to maturity or yield to the next put for the current yield. However, this again implicitly assumes a conversion probability of 100%, and excludes the possibility of default by the issuer.

Analytical Valuation Models

Virtually all valuation models for convertible securities currently in use by market professionals follow the economic framework of contingent claims analysis pioneered by Fischer Black, Myron Scholes, and Robert Merton.39 The models differ from each other in the number of stochastic variables used in their construction.40 The simpler one-factor model assumes that the stock price, or more correctly, the stock return, is the only underlying stochastic variable. All other items that impact on the value of a convertible are descriptors and variables. The more complex two-factor models assume both stock returns and interest rates to be stochastic and are discussed below.

Descriptors and Variables That Affect Convertible Valuation

Descriptors are the attributes of a security that are known with certainty, such as its stated maturity, coupon, and call and put schedules. Variables are inputs that can be estimated, albeit with estimation error. Examples include future dividends and the costs involved in hedging the security. Descriptors that affect the value of a convertible security include:

• Spot price of the underlying security: The higher the stock price, the more the conversion option is likely to be in-the-money (or less out-of-the-money), and hence the higher the value of the convert.

• The dividend yield of the underlying common stock: The higher the dividend yield of the underlying stock, the lower the value of the convert as it results in a lesser yield advantage thereby reducing the attractiveness of the convert as an alternative to the common stock. Looked at another way, a higher dividend restrains the stock price appreciation and the convert’s potential to go in-the-money. The same logic holds for the dividend growth rate. Most new issue converts have a dividend protection clause that compensates the investor in cash or decrease in the conversion price if the dividend payout on the common stock exceeds a prespecified level.

• Coupon or preferred dividend: The higher the distributions from the convert, the higher the yield advantage and hence the higher the value of the convert.

• Issuer redemption: A longer noncall period increases the value of the convert in two ways. First, the investor enjoys the yield advantage for a longer period. Second, absent a voluntary conversion by the investor, the minimum maturity of the conversion option equals the convert’s first redemption date; hence the longer the conversion option, the higher the value of the convert. A hard noncall is worth more to the investor than a soft call of the same maturity.

• Maturity: Consider two converts identical in all respects except their maturity dates. The longer maturity convert will have the lower value. This may seem contradictory because we know that the longer the maturity of a call option, the higher will be its value. But while longer maturity does increase the value of the conversion option, it is swamped by the decrease in the value of the bond floor caused by discounting the cash-flow stream at a higher rate over a longer period. For deep-in-the-money converts, the direct impact of increasing rates is smaller because conversion value of the convert acts as the lower bound. However, if rate increase impacts the stock price adversely, which is plausible, then the second order impact of rates on deep-in-the-money can also be negative.

• Investor put: Redemption at maturity is the equivalent of an investor put at maturity. A convert with a put prior to maturity will be worth more than one without. The earlier the put date, all else being equal, the higher the convert’s value; also, the higher the put redemption level, also called the put price, the higher the convert’s value.

• Liquidity: The more illiquid the convert, the lower the value of the convert as even moderate size trades are likely to materially change convert prices, causing sellers to realize less than they otherwise would and buyers to pay more. As seen during the 2007–2008 period, market illiquidity caused convert prices to fall quite dramatically as hedge funds needed to sell positions to meet client redemptions. Not surprisingly, the most liquid converts were the easiest to sell, although at discounted prices. Even though market volatility increased, the implied volatility of the convertible securities fell. In other words, the pricing curve of convertible in Exhibit 42–2 declined. Conversion premiums did “not open” or increase with declining stock prices—as would be expected under normal market conditions—during this period of illiquidity. Thus even positions held by better financially better situated funds and outright funds experienced mark-to-market looses. The notion of “illiquidity premium” became more relevant.

• Borrow costs: Increase in the cost to borrow stock effectively has the same impact as an increase in the dividend of the underlying stock. When the convert is illiquid and/or the stock borrow cost excessive, the convert may trade below parity, leading investors to voluntarily exercise their conversion option, which normally they would not. Outright investors are also affected as increased hedging costs to investment banks’ trading desks are likely to result in wider bid/offers, smaller transaction sizes or accepting the outright investors’ sell order on a “work the order,” which entails the investor holding the position until another buyer is found and having to bear market exposure until the position is sold.

• Country risk: As with other non-domestic securities, country risk assessment needs to be balanced against economic growth potential in general, and that of the underlying stock in particular. Not surprisingly, therefore, there is generally less exposure to non-U.S. converts in most U.S.-based outright portfolios. International funds, specific regional funds, and hedge funds account for the bulk of the investment pool for non-U.S. converts as they they may have a wider array of securities to hedge currency risk as well as at least a part of the country risk. As a general rule, converts originating from countries with perceived higher country risk typically are issued at lower premiums, or equivalently, their equity volatility is not fully priced. On the other hand, converts from large multinational firms, especially from the G-10 countries, are well received when the implied corporate credit rating is high and the country risk low.

Candidate stochastic variables used to model the value of a convert include:

• Stock returns: This is the most basic explanatory variable, and is part of all convertible valuation models. A single factor model assumes stock returns to be the sole stochastic variable and posits a behavior of stock returns and variance.41 Not surprisingly, since volatility plays a crucial role in valuation of options, it does so too in the valuation of convertibles. Some models use a flat volatility as an input for all time and stock price levels, whereas the more sophisticated ones use a term structure of volatility, and yet others may also incorporate option volatility skew wherein the volatility estimate depends on the extent the option is away from the at-the-money strike at each stock price as the stock price evolves over time.

• Interest rates: Valuation models for bond options have interest rates as the main stochastic variable. Since the price dynamics of a convertible are also influenced to a considerable degree by the straight bond component and its convexities, it stands to reason that two-factor convertible models include interest rates as the second factor. Its volatility, called the yield volatility, is an estimated parameter, analogous to stock return volatility in the single factor model.

As stated, higher interest rates reduce the value of the bond floor of a convert by discounting the convert’s cash flows at the higher rate. The impact of interest rates on the embedded options is more complex. An increase (decrease) in the interest rate increases (decreases) the value of the conversion option, and the reverse for the option to put the convert, if there is an investor pre-maturity put feature. From the issuer’s perspective, if the convert is out-of-the-money, higher (lower) interest rates will reduce (increase) the value of the issuer’s call option, as it would entail financing the redemption value by new debt at a higher (lower) rate. In the case of in-the-money converts, which should in most cases be called as soon as possible, the issuer’s incentive for a conversion-forcing call will increase with rising interest rates.

• Credit-spread: The lower the credit quality of the issuer, the higher the probability of default, and hence the higher the credit-spread. For example, a Baa3/BBB- rated issuer may have a credit-spread of 210 basis points for a five-year maturity subordinated debt. If the rating were a notch lower at Ba1/BB+, the spread could widen by a further 50 to 150 basis points or even wider.42 Thus spreads impact on converts in the same direction as do interest rates. Credit-spread is increasingly viewed as a stochastic variable in its own right and its volatility is tracked very closely.43 Development of liquid CDSs on individual corporate issues, standardization of swap languages, and liquidly traded index CDSs as well as asset swaps allow investors to hedge credit risk for a majority of investment grade issues and many non-investment grade issues. Credit-linked products are an exciting growth area for convertible investment and arbitrage trading as also in relative value capital structure and equity volatility trading.

• Exchange rates: Consider a US$ denominated bond—both par and coupon are US$ denominated—exchangeable into shares of a UK pound (GBP) denominated underlying stock. In addition to the equity risk associated with the investor’s conversion option into the underlying ordinary shares, a U.S.-based investor is exposed to exchange rate risk because the shares are denominated in a different currency. With the number of shares per bond fixed, any increase in the value of the GBP against the US$ would benefit the investor, and any decline reduce the value of her position. Thus the investor thus has an embedded call on GBP, or equivalently, an embedded put on US$, in the convert.

Since exchange rates are stochastic, they could potentially be an additional factor in the valuation of a convert. Exchange rate volatility would have to be estimated.

Analytical Valuation Models and Factor Choices