CHAPTER

FOURTEEN

CONVERTIBLE SECURITIES AND THEIR INVESTMENT APPLICATION

Executive Vice President

Pacific Investment Management Company

CHRIS P. DIALYNAS

Managing Director

Pacific Investment Management Company

A convertible bond is a debt security that allows the holder to convert to a given number of shares of a company’s equity. This convertibility to equity means that the holder of a convertible bond will profit from a significant increase in the firm’s stock price while being protected against lower stock prices through his debt claim. In this chapter we will first discuss some key terms and the basic features of convertible bonds, and then describe the motivations for issuing these securities and the key portfolio management considerations for investing in them, and finally give an overview of the major factors involved in their valuation.

BASIC CHARACTERISTICS OF CONVERTIBLE SECURITIES AND KEY TERMS

Conceptually, a typical convertible bond is a combination of a debt claim and a call option on the firm’s equity. However, the type of performance profile and the nature of the risks that a given convertible bond will generate will be driven by the interaction among several features of the security.

Nature of the Debt Claim

The seniority of the underlying debt claim in a convertible bond is one of the most important considerations in assessing the strength of the security’s “bond floor” (and by extension, determining whether the bond is likely to be positively or negative convex under a large downward move in the equity price). Convertible bonds will often be senior unsecured claims, but they are also frequently subordinated debt or preferred stock. In the case of preferred stock, deferral of coupons is generally not an act of default for the issuer, and nonpayment of coupons is frequently not cumulative. A convertible with a senior debt claim will exhibit much more positive convexity than subordinated debt or preferred stock, and an investor will therefore demand a higher coupon (wider credit spread) for more junior securities.

In order to assess the appropriate excess credit-spread for subordinated debt or preferred stock vis-à-vis senior debt, an investor needs to consider the likely range of potential recoveries of each tranche of debt in the event of default, as well as its relative thickness as a percentage of the overall enterprise value of the firm. (For a typical company where the enterprise value is well in excess of its liabilities, an investor should demand a wider credit-spread for a thinner part of the capital structure given an equal amount of subordination.) Additionally, while the credit component of a senior unsecured convertible bond is often able to be hedged using credit default swaps (CDS), CDS referencing subordinated debt and preferred stock are generally not traded in the marketplace.

Another common type of convertible security, aside from those with an underlying claim at the senior unsecured, subordinated, or preferred part of the capital structure, are “mandatory” convertibles. These securities are not really bonds at all. In the most typical structure, the investor receives a coupon based on the par value of the security while selling an at-the-money put option and buying an out-of-the-money call option on the issuing firm’s common stock. At maturity, the mandatory convertible converts into common stock, paying the investor par if the stock price is between the put and call strike, while the investor takes direct equity exposure if the stock is below the put strike or above the call strike. Mandatory convertibles are effectively thus just long positions in the issuing firm’s equity, and most investors who buy these securities do so either for income enhancement or because they are not able to take direct equity positions.

Coupon Payments

Historically, one of the primary advantages of convertible bonds to issuers is their relatively low coupon payments. Investors are willing to accept a materially lower coupon than in the case of a nonconvertible debt security because of the equity call option embedded in the convertible. Coupons are generally fixed-rate as opposed to floating, and zero coupon convertibles are not uncommon. In considering how to structure a new convertible security, the issuer must weigh the tradeoff between lowering its coupon expense versus increasing the likelihood of dilution in the case that the bond is converted to equity (i.e., selling an equity option of greater value).

Equity Conversion Rights

The equity call option embedded in a convertible bond is in the form of a conversion ratio, giving the holder of the bond the right to a given number of equity shares per a given bond face value. This ratio implies a conversion price (that is, the strike price of the embedded equity call option), which is simply the face value of the bond divided by the conversion ratio; for instance, a $1,000 par convertible bond with a conversion ratio of 25 will have a conversion price of $40. Market participants often refer to the distance between the current stock price and the conversion price in terms of how far “up” the conversion price is; for instance, one might say that a new deal coming to market is “3%, up 25,” meaning that it carries a 3% coupon and its conversion price is 25% above the current equity price.

Another concept related to a convertible’s equity component is the security’s parity, which is simply the conversion ratio multiplied by the market price of the common stock. Participants will often refer to the valuation of convertibles (particularly those that are deep in-the-money) in terms of their “point premium” to parity; for example, if the parity of a convertible is $80, and its price is $105, one would say that it trades at a twenty-five point premium. Alternatively, participants will refer to a convertible’s conversion premium, which is simply the percent premium to parity of the instrument ([convertible price – parity]/parity).

Finally, the convertible’s delta refers to the sensitivity of the bond price to an incremental change in the underlying equity. Delta is most frequently expressed relative to parity; so if the delta of the bond in the prior example were 50%, this would mean that a 1% increase in the stock would be expected to result in a $0.40 increase in the convertible’s price (1% × 50% × 80). Alternatively, delta can also be expressed relative to the price of the convertible itself (often called outright delta), which in the previous example would be 38.1% (i.e., 0.4/105). Expressing delta relative to parity or the bond price is often referred to as “hedge delta” or “outright delta,” respectively.

Call and Put Options

It is very common for convertible bonds to include a series of call options giving the issuer the right to repurchase the bonds as well as put options giving the holder the right to sell the bonds back to the issuer at specified price. These calls and puts often occur at the same or very close dates, and so effectively serve to shorten the maturity of the convertible bond. While the presence of these calls and puts greatly complicates the valuation of a given convertible bond, they are very common features as they help to optimize the tax and accounting advantages of the security to the issuer.

Dividend Protection

Dividend protection features are intended to compensate the convertible bond holder for dividends paid to common equity holders. For securities that do not carry such provisions, the payment of dividends negatively impacts the bond holder as the convertible will not receive the dividend payment yet will suffer from the drop in the stock price after the dividend is paid. To remedy this, most convertibles now feature a conversion ratio adjustment feature, which changes the conversion ratio in proportion to any dividend announced. That is, if the company announces a dividend that is 2% of its share price prior to the announcement, the conversion ratio will be changed such that the conversion price falls by 2%.

Takeover Protection

Similar to dividend protection, takeover protections are features meant to protect a convertible bond holder against corporate actions that would otherwise adversely affect the bond’s value. Takeover protections can take several different forms, including an adjustment of the conversion ratio (as in the case mentioned in the preceding) or the right to convert into the acquirer’s stock at a new ratio intended to be a “make whole” value. Careful consideration of a given convertible’s takeover protections are very important, as the provisions can differ significantly from bond to bond.

Other Features

Net share settlement, contingent conversion (CoCo), and contingent payment (CoPa) are other common features of convertible securities, particularly those issued before 2008. Historically, the primary motivations behind each of these provisions has been to minimize a convertible’s equity share dilution and interest expense for accounting purposes while maximizing its tax benefits in terms of interest deductions to taxable income (more on this point in the following section on the motivations behind issuing convertible securities).

Net share settlement, in its most basic form, allows the issuer to meet its conversion obligation by paying the par value of the bond in cash and only issue shares for the portion of the conversion value that is above par. In some cases, this provision will be stated such that the issuer has the option to settle the bond at conversion using a combination of cash and stock at its discretion. The motivation behind this provision has historically been to minimize the issuer’s equity dilution for EPS accounting purposes, but accounting changes in 2008 have greatly reduced the advantage of this provision.

Contingent conversion (CoCo) features prohibit conversion until a given threshold in the equity value has been reached (commonly 130% of the conversion price). This feature has historically been used to garner both accounting and tax benefits for the issuer, but this motivation has been greatly reduced over the past two years given tax and accounting guideline changes.

Bonds with contingent payment (CoPa) provisions will pay a higher rate of interest if a given trading level of the equity is reached (for example, 130% of the conversion price). This feature has traditionally been used as a way to receive favorable tax treatment from the issuance of convertible securities, allowing issuers to expense the equivalent straight debt interest cost for tax purposes while only actually paying the lower (sometimes zero) convertible coupon interest.

Convertible Bond Return Profile

While generally highly complex securities, convertible bonds can be thought of conceptually as a combination of a corporate bond and an equity warrant. For equity values that are at or above the convertible’s “strike” (that is, the price at which the implicit call option gives the holder the right to purchase equity shares), they will behave a lot like an equity option (and thus like a direct equity investment when deep in-the-money) while for equity values well below strike, and thus deeply out-of-the-money, they will behave mostly like a corporate bond.

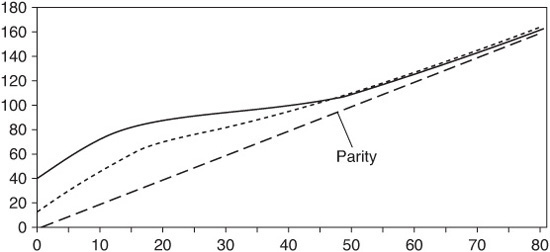

Their hybrid nature gives convertible bonds a dynamic convexity profile, as shown in the stylized example in Exhibit 14–1. As shown in the exhibit, a typical convertible bond will be a positively convex instrument for equity prices roughly 30% below its conversion price and above, but then will generally become negatively convex (as with most corporate bonds) as the equity price trends toward zero and bankruptcy risk becomes dominant. This convexity profile makes convertible bonds a very interesting asset class, and requires that investors understand both the equity and debt part of the issuer’s capital structure and the likely interaction between the two.

EXHIBIT 14–1

A Typical Performance Profile of a Convertible Bond

OVERVIEW OF CONVERTIBLE BOND VALUATION AND RISK METRICS

While conceptually a convertible bond is a combination of a risky bond and a stock warrant, a convertible’s valuation is not as straightforward as simply pricing these two components separately. For one, convertible securities are generally not able to be physically split into their equity warrant and bond components. In addition, calls and puts, allowing the issuer or holder to redeem the securities early, complicate valuation further. Finally, the convertible’s sensitivities to both credit-spread moves and equity price moves will dynamically depend on both of these factors. For instance, a deep in-the-money convertible will have virtually no credit-spread risk, while a distressed convertible can have an equity delta approaching one. (Consider a company in which recovery on default is zero as the equity price trends toward zero.) As a result of these complications, valuation of convertible bonds does not present a closed-form solution that captures their full complexity. Instead, the primary valuation methods used by market participants center on simulating possible paths of the stock price and accordingly, the convertible bond, at different points in time, generally using either binomial trees or so-called finite difference methods, which use a partial differential equation for the convertible price as a function of the stock price and time. While not going into the technical specifics of these models, this section focuses on the major inputs to such models and the primary differences among them, then describes the major risk metrics generated by any pricing model.

Stock Price Evolution

The most basic part of any model for valuing convertibles will be projecting the future evolution of the stock price across time. Equity volatility will describe the nature of the process, either through incremental steps in the case of a binomial tree or by helping to define the diffusion process in a partial differential equation approach. Given this path of future stock prices, values of the convertible bond across time are then populated by starting with the potential values at maturity and then working backward. Upon maturity, the value of the convertible bond will be the greater of parity and the bond’s principal value (plus any final coupons), while at any given point prior to maturity the bond value will be the present value of its probability weighted future cash-flows. In addition, the bond’s call and put schedule, if applicable, will be featured in this process, thus affecting the potential price paths for the convertible security. This basic structure of defining a process for future equity values, then working backward from maturity to value the possible values for the convertible bond given a stock price, is common across the vast majority of convertible bond pricing models. The key areas in which these models will differ are, first, in the method used to discount future cash-flows, and, second and most importantly, in what relationship is assumed between the evolution of the stock price and credit-spreads.

Discounting Methods

There are two basic approaches to discounting the possible future values of the convertible in order to obtain a present value, namely “blended discount” and “full discount” approaches. In a blended discount approach, the convertible is separated into its equity and bond components, and the two are discounted at different discount rates; the bond component at a risky rate including the issuer’s credit-spread while the equity is generally discounted using the risk free rate (as the equity price already includes a risk premium). Exactly how the convertible is decomposed into its equity and bond components can differ across models, but one typical approach is to separate out the actual cash-flows at any given point into bond (i.e., if not converted) and equity (i.e., if converted) components.

Alternatively, convertible pricing models may also use a full discount approach, where one discount rate is used for all cash-flows. The basic rationale here is that a portfolio can be constructed of a long position in the convertible bond and a short position in the equity, whereby the only risk to this portfolio is the instantaneous default of the issuer, and the risk premium for this risk is captured by the convertible bond’s credit-spread. While the differences in these two discounting approaches can result in meaningful differences in a convertible’s theoretical price and delta given common inputs, these differences are relatively minor compared with the impact of incorporating credit-spreads as a stochastic factor.

Incorporating Credit Risk

Most convertible bond models today will incorporate a dynamic relationship between the equity price and credit-spreads. That is, they will seek to capture the intuitively obvious phenomenon that credit risk generally increases as the equity price falls, with this relationship becoming highly nonlinear as the equity price trends toward zero. Incorporating credit-spreads as a stochastic factor that is a product of the equity price will result in a lower theoretical value for the convertible bond and a higher equity delta, lower vega, and higher implied volatility, all else being equal. This change in valuation and risk metrics is capturing the fact that the more sensitive the credit is to the equity, the less of a “bond floor” the convertible offers and hence the less valuable the equity “option” embedded in the security becomes.

The exact method of relating changes in the credit-spread to the stock price can be considered to be the key difference among various convertible bond pricing models. One common way of establishing this relationship is by using a decay factor that defines the future credit-spread given an equity price, such that Ct = C0(S0/St)k, where k is the decay factor, Ct is the future credit-spread, C0 is the current credit-spread, S0 is the current stock price, and St is the future stock price. Thus, the credit-spread trends toward infinity as the stock price approaches zero, although further parameters can be added so that the minimum price of the bond is set at an assumed recovery rate. While this approach is certainly an improvement over holding credit-spreads constant in projecting future values for the convertible, for a constant value of k, the decay factor, it will likely miss the very different credit convexity for a given move in equity price for highly leveraged firms. (Consider the different proportionate effect on credit-spreads for a 50% decline in equity value of two firms, one with debt to enterprise value of 10%, the other 90%.) Another, far more complicated, alternative is to explicitly model the future paths of the firm’s enterprise value, with equity prices and credit-spreads a function of this process using a version of a Merton capital structure model. While both of these approaches are used in the market place, widely used third part pricing engines such as Bloomberg and Kynex use the decay factor approach, and users can change the value of the decay factor to reflect differences across capital structures.

Major Convertible Bond Risk Metrics

1. Delta: As mentioned, this captures the change in the convertible’s value for a given percentage change in the equity price. All else equal, incorporating credit-spreads as a dynamic factor will increase the delta of a convertible bond, thereby compensating for the deterioration of the bond floor as equity prices fall. Delta is most frequently expressed relative to parity; so if the delta of a bond with parity of 80 and price of 105 were 50%, this would mean that a 1% increase in the stock would be expected to result in a $0.40 increase in the convertible’s price (1% × 50% × 80). Alternatively, delta can also be expressed relative to the price of the convertible itself (often called outright delta), which in the previous example would be 38.1% (i.e., 0.4/105). Expressing delta relative to parity or the bond price is often referred to as “hedge delta” or “outright delta,” respectively.

2. Gamma: As with other options, gamma captures the incremental change in delta given a change in the underlying equity price. One of the keys to successfully managing convertible bond portfolios is understanding when a given bond will switch from having positive gamma to negative gamma as the stock price falls, which will in turn be driven by the expected behavior of credit-spreads and bond recovery upon bankruptcy. A graphical illustration of this is shown below in Exhibit 14–2. (The dotted line depicts a recovery of 10, the solid line a recovery of 40.)

EXHIBIT 14–2

Impact of Different Recovery Rates on Convertible Convexity Profile

3. Vega: This refers to the change in the value of the convertible given a change in equity implied volatility. All else being equal, vega will be lower if a higher degree of credit sensitivity to equity is assumed. In fact, given a high credit to equity sensitivity, it is possible for vega to become negative given a high enough level of equity implied volatility (given that very high levels of equity volatility imply a meaningfully higher probability of distress).

4. Rho: The interest rate risk of the convertible, equivalent to a vanilla bond’s modified duration.

5. Credit-spread duration: The convertible’s sensitivity to a change in credit-spreads. In considering how to hedge both the equity and credit risk of a convertible bond, it is important to be aware of what assumptions are being used to calculate the security’s delta. For example, if a dynamic model that incorporates changes in credit-spreads given changes in the equity is being used, the delta is implicitly incorporating the sensitivity of the security to incremental moves in credit quality. As a result, hedging both the full delta given by such a model as well as the full spread duration will overhedge the position for local moves in the equity and credit. If it is desired that both risks be hedged independently, it is more consistent to use an equity delta that does not incorporate the relationship between equity and credit-spreads. As a matter of practice, an equity hedge is generally the best hedge for incremental moves in the equity while credit default swaps provide an effective hedge against a downward jump in equity prices and credit quality.

6. Bond floor: Also sometimes referred to as “investment value,” this is simply the value of the convertible if it were treated as a straight bond discounted by an appropriate risky discount curve. An investor should always be aware of how far away this measure is from the market price of the convertible, and using scenario analysis to shock the bond floor based on various adverse credit-spread assumptions can give a good sense of what the “worst case” outcome for a position is and what an appropriate hedge might be.

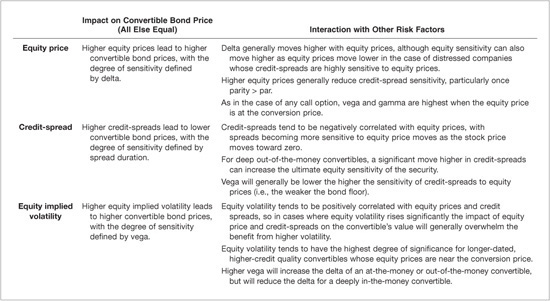

In addition to directly affecting the valuation of a convertible bond, each of the primary risk factors of equity price, credit-spread, and equity implied volatility also interact with one another to drive performance. Exhibit 14–3 summarizes the impact of each of these factors as well as the interaction among them.

EXHIBIT 14–3

Summary of the Impact of Major Convertible Bond Risk Factors

PRIMARY INVESTORS IN CONVERTIBLE BONDS

Given the relative complexity of the asset class, the convertible bond market has historically been dominated by specialized investors, namely convertible arbitrage hedge funds and dedicated outright (i.e., long only) convertible bond funds. Aside from these two core constituencies, which together have represented around 75% or more of convertible bond holdings and secondary market flows over the past 10 years, other primary investors in convertible bonds include equity and high-yield mutual funds. In general, the primary motivation for investing in convertible bonds as an asset class lies in the positively convex return profile offered by the securities, allowing investors to benefit from a significant rally in equities while lessening losses in an adverse market environment. Since 2000, convertible bonds have outperformed the S&P 500, and convertible arbitrage funds have done better than an outright investment in a convertible bond index (Exhibit 14–4). However, convertible bonds saw extreme price moves during the financial crisis, with the Bank of America-Merrill Lynch index falling 32% from August 2008 to February 2009 as compared with a 43% fall in the S&P 500. During this period, convertible bonds suffered not only from a sharp decline in stocks and widening in credit-spreads, but also were directly impacted by hedge fund deleveraging given that alternative investors were the primary holders of the asset class at the time.

EXHIBIT 14–4

Total Return of Performance of Convertible Bonds versus Equities

Convertible Arbitrageurs

Convertible arbitrage hedge funds emerged as the dominant players in convertible bonds in the late1990s, and by 2008 made up approximately 80% of the market in terms of daily trading volumes and a comparable share in terms of ownership. While that share has fallen since the credit crisis of 2008 due to less freely available leverage, these investors still represent around 40% of convertible bond ownership and 50% to 75% of daily trading volumes.

Convertible arbitrage involves purchasing a convertible bond, then attempting to hedge out the equity component by selling short the common stock; the hedge ratio is given by the bond’s equity delta. This strategy is intended to provide returns that show low correlations to the equity market and a high information ratio. The rationale behind convertible “arbitrage” is that the equity option component of convertible bonds tends to be systematically undervalued, allowing the arbitrageur to purchase this option at an attractive level of implied volatility and profit by extracting the gamma presented by significant moves in the common stock (i.e., delta hedging). As such, these investors will typically focus on convertibles in relatively volatile names where the stock price is approximately 80% to 130% of the conversion price, maximizing the convexity profile of a delta hedged convertible bond position. In addition, deep in-the-money convertibles trading at low premia to parity can provide very attractive convexity profiles to such investors by offering a cheap implicit put option on the stock.

The most important risk factor in a delta hedged convertible bond position is the residual credit-spread/default exposure embedded in the position, and an investor can attempt to hedge this risk in two primary ways. First, and most directly, he can hedge the default risk by purchasing a credit default swap (CDS), presuming that such derivatives exist for the part of the capital structure corresponding to the convertible. This gives a clean hedge to a widening in credit-spreads or jump to default, but materially reduces the carry of the position. Further, if the underlying equity rallies and the convertible becomes deep in-the-money, the sensitivity to credit-spreads will become greatly reduced, and the investor will need to adjust the CDS hedge, paying additional bid/offer costs, lest he become net short spread duration. Second, the arbitrageur can seek to adjust the equity hedge ratio to compensate for the residual credit risk. Convertible bond pricing models that incorporate credit-spreads in projecting a range of possible stock prices will give a higher equity delta for issuers with wide credit-spreads; that is, the sensitivity of credit-spreads to a change in the stock price will be incorporated into calculating the convertible’s delta. This approach suffers from model uncertainty, as it relies on an assumption about the correlation between credit-spreads and equity prices in order to adjust the hedge ratio. Given that the relationship between credit and equity can be highly unstable, this approach to hedging the credit risk of a convertible bond exposes the investor to shifts in this relationship, where movements between the two decouple. However, hedging the credit component with additional equity as opposed to CDS has the advantage of offering greater carry and also makes for a simpler overall position (as opposed to having both equity and CDS hedges). In practice, outside of highly stressed companies, convertible arbitrageurs will tend to hedge primarily with equity alone, adjusting their hedge ratio upward if they wish to offset the credit-spread exposure.

Dedicated Outright Convertible Bond Funds

Other primary investors in convertible bonds aside from convertible arbitrage hedge funds are funds specializing in managing portfolios of convertible bonds on an outright (i.e., unhedged) basis, with many managing against a convertible bond index. So-called outright players (both dedicated to convertible bonds and those focused on equities) were dominant in the early to mid 1990s, but saw their share of the market reduced to only approximately 10% to –20% by 2005 as convertible bonds became predominantly a hedge fund product. However, after the financial crisis in 2008 these participants became far more important to the market as the hedge fund universe shrank and the remaining hedge funds greatly reduced their leverage. As of 2010, dedicated outright convertible bond funds make up around 15% to 20% of ownership and daily trading volumes.

These investors will consider the same sorts of issues as a convertible arbitrageur when considering which convertible bonds to buy, but unlike an arbitrageur, their views on a given company’s equity valuations will be central to performance versus their peers. Along the equity sensitivity spectrum, these funds tend to focus on convertibles with a “balanced” profile, where underlying equity prices are between 80% and 120% of the conversion price, and will generally favor convertibles of more stable companies vis-à-vis convertible arbitrage funds.

At the portfolio level, an outright fund is essentially managing a book consisting of long positions in equity, credit, equity volatility, and interest rate risk, and so must consider his or her views on all these factors accordingly. In practice, the equity risk factor will be the most dominant for an outright fund’s performance, although credit risk will play an extremely important role as well. Aside from extremely stable environments for risk assets, the equity volatility and interest rate risk components will tend to be of lesser importance to total returns (the latter on account of most convertible bonds having relatively short effective durations).

Equity and High-Yield Funds

Finally, convertible bonds will frequently see crossover interest from investors primarily focused on equities or corporate credit. In the case of equity investors, they may favor a convertible bond over a direct investment in the equity if there is an income advantage presented by the bond’s coupon or if downside protection is desired and the convertible is seen as a cheaper way of acquiring this than buying equity puts. Not surprisingly, equity investors tend to be most involved in high delta, equity-like convertible bonds. On the opposite end of the spectrum, high-yield bond funds and other corporate credit investors will also invest in convertible bonds, primarily focusing on “busted” issues that trade with little to no equity delta. Here, the convertible bond will be favored if it offers more attractive valuations (i.e., wider credit-spreads) than the nonconvertible bonds in a given company’s capital structure.

For any investor, the most critical investment consideration specific to investing in a convertible bond lies in assessing the extent to which there really is a bond “floor,” or put another way to what extent the investor is purchasing a call option on the stock as opposed to simply getting outright equity risk.

MOTIVATIONS BEHIND THE ISSUANCE OF CONVERTIBLE SECURITIES

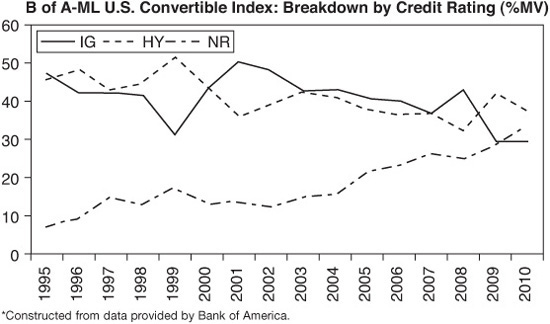

Given that convertible bonds are simply a combination of other types of securities available as funding sources for companies, it begs the question as to why companies issue these instruments in the first place. The answer lies in market segmentation effects (making debt issuance unattractive for small, poorly understood companies), a combination of historical tax and accounting benefits, as well as unique opportunities provided to companies by convertible securities to tactically sell their equity at attractive levels. As tax and accounting benefits of convertible bonds have lessened over the past few years this has helped to make investment grade firms a much smaller share of the convertible market (down from 50% in 2001 to under 30% in 2010), while the prevalence of convertible arbitrageurs has helped to drive an increase relative issuance among small firms not followed by credit rating agencies, as shown in Exhibit 14–5.

EXHIBIT 14–5

Composition of the Convertible Market by Credit Rating

Companies That Cannot Access the Straight Debt Market

For public companies that are relatively small, not followed by institutional fixed income investors, and who do not have a credit rating from any of the agencies, convertible bonds can be an attractive alternative to raising additional equity capital. If such a company views its stock as undervalued, it can issue a convertible bond with a conversion price at a level that it would be comfortable issuing additional equity, and pay a far lower interest expense than if it tried to bring a debut deal to the high-yield market. Further, many companies will purchase a call spread (i.e., buying a call with a strike price equal to the conversion price and selling a call that is further out-of-the-money) on their own stock as part of a convertible issuance, thereby further increasing the stock price at which actual further dilution will occur.

In addition, many companies undergoing financial distress will use the convertible market to raise capital for similar reasons as those cited above. Yields offered to such firms in the market are likely to be prohibitive, and the company will be motivated to seek alternatives to raising equity at “fire sale” prices. In the case of both these types of firms, the prevalence of convertible arbitrage hedge funds makes the convertible market a viable source of funds in that it allows companies to raise capital from investors that are generally agnostic about its future growth prospects and who are instead simply looking for securities with attractive convexity properties.

Tax and Accounting Benefits

Much of the convertible issuance by investment grade rated companies in the 2000s was motivated by accounting and tax advantages offered by the securities. In particular, the accounting treatment of net share settlement and contingent convertibility allowed the companies to suffer little to no equity dilution from the issuance of convertible bonds, making them particularly attractive versus issuing equity. Additionally, companies could often deduct a far larger interest expense for tax purposes than was required to be expensed for generally accepted accounting principle (GAAP) earnings, which combined with the lack of dilution made convertible bonds a highly attractive means of earnings per share (EPS) management for higher quality firms. However, accounting changes made in 2008 have greatly reduced the accounting advantages of convertibles using net share settlement by forcing companies to split out the accounting for the securities into their debt and equity components, thereby closing most of the asymmetry between how interest expense is recorded for earnings reporting and tax purposes. While the full details of these accounting and tax changes is beyond the scope of this chapter, they have served to greatly reduce the motivation for investment grade firms to access the convertible bond market.

Opportunistic Issuance

A final reason that a firm may issue convertible bonds is as a means of taking advantage of what it sees as an opportunity to sell its equity or equity volatility at attractive levels. Given that they can be classified as 144A private placements, convertible bonds can be brought to market much more quickly than an issuance of additional common stock. As such, if a company has seen a significant rally in its equity prices, and sees significant further increases as unlikely or as an opportunity to raise additional equity, it can issue a convertible bond with a conversion price equal to where it would willingly issue common stock. Further, depending on the equity volatility skew companies may purchase a call spread along with the issuance of a convertible, thereby granting the obligation to issue shares at a significant premium while capturing a low cost of debt.

KEY POINTS

• Convertible bonds combine components of an equity and debt security, becoming increasingly like common stock given higher equity prices and increasingly like straight debt for lower equity prices.

• As a result of this hybrid nature, convertibles can be highly convex securities, and this aspect has made them particularly attractive to hedge fund investors.

• However, in analyzing a convertible bond as a potential investment, an investor must carefully scrutinize the credit quality of the given issuer as well as its potential growth prospects and equity upside.

• Convertible bonds issued by companies with poor credit quality will have weak “bond floors” and thus will not offer positive convexity across a large range of possible stock prices. Accordingly, many convertible bonds will switch from being positively convex to negatively convex instruments as a company’s stock price falls.

• Companies issue convertible bonds for a variety of reasons. The most straightforward motivation to issue convertibles is in the case of companies that cannot access the straight debt markets, but issuance can also be driven by tax and accounting advantages as well as a company’s view on the potential for its stock to appreciate beyond a certain price.