CHAPTER

TWENTY-TWO

COVERED BONDS

Financial Consultant and Visiting Faculty

Indian Institute of Management Calcutta, India

As financial intermediaries create and hold financial assets, they search for a variety of ways to refinance them. Corporate bonds are the most traditional form of capital market-based refinancing. However, corporate bonds are a direct exposure on the issuer and are directly affected by the financial strength of the issuer. The issuer’s rating determines the rating of corporate bonds. Obviously, over a period of time till maturity, these bonds are affected by the changes in the rating of the issuer, as also is the probability of default.

A country’s financial system may, for a variety of reasons, want financial instruments that are either unaffected or less severely affected by the credit and rating of the issuer. Assume an issuer is creating or holding standard financial assets, such as prime mortgage loans. If a system of refinancing these mortgages allows investors legal access to the portfolio of assets, investors will prefer a claim over a pool of healthy assets over a claim over the issuer. From a policy perspective, if an issuer is allowed to issue bonds that are either solely based on the strength of the asset pool, or at least derive from the same, the issuer may hopefully issue better rated bonds, and therefore, raise relatively cheaper financing to be able to create and hold the pool of assets in question. If an issuer had to depend on corporate bonds, a low-rated issuer would not be able to raise cheaper financing, and therefore, hold healthy assets. This leads to a self-sustaining cyclicality whereby a weaker bank must hold inferior quality assets, and therefore, remain weak or become weaker.

In the world of fixed income securities, markets have been searching for instruments that are asset-backed, rather than entity-backed. Mortgage-backed and asset-backed securities are instruments that seek to detach completely from the rating of the issuer and depend entirely on the quality of the pool of assets and the structural credit enhancements, mostly to reach highest ratings. Covered bonds, the subject of this chapter, are alternative instruments that may be perceived as midway between corporate bonds and mortgage-backed securities, in the sense that they depend both on the quality of the issuer and the quality of the assets underlying the funding.

COVERED BONDS: FROM EUROPE TO THE REST OF THE WORLD

In an environment of institutional investing that is so heavily reliant on ratings of investment options, both mortgage-backed securities and covered bonds are devices to uplift the rating of the instrument above the rating of the issuer. In case of mortgage-backed securities, under an assumption of complete independence of the funding from the risks of the issuer, the securities often get highest ratings. These ratings, and the strength of the security that they evidenced, came under acute challenge during the subprime crisis of 2007–2008, making mortgage-backed securities at least periodically unpopular. The search for an alternative ended at covered bonds, which have been used in Europe over decades. Covered bonds do not have the fascination of mortgage-backed securities, but in the environment prevailing during and after the subprime crisis, the historical strength of covered bonds was far more appealing than the attractiveness of mortgage-backed securities.

Covered bonds, as an instrument of mortgage funding, have a long history. They are first said to have been issued in Germany, then Prussia, in 1769. The first issuance in Denmark happened in 1797 after the fire of Copenhagen in 1795. They are known by variety of names over Europe—pfandbriefe in Germany, realkreditobligationer in Denmark, obligations fonciers in France, and pantbrev in Spain, for example. Covered bonds have been essentially a European instrument, mostly backed by specific laws, until recently when countries outside Europe either started enacting legislations to promote covered bonds, or structurers used combination of securitization-type structuring devices using common law to create covered bonds.

In the United States, Washington Mutual became among the first to come up with U.S. covered bonds in September 2006, followed by Bank of America in the next year. Post the subprime crisis, then-U.S. Treasury Secretary Paulson came out with the Treasury’s plan to promote covered bonds, including a statement of best practices. This created a promise that the United States, with its vast and unarguably the world’s largest mortgage finance market, would join the list of countries that use covered bonds. Later, in March 2011, a Covered Bond Act of 2011 was presented as HR 940. Other countries too have taken legislative or regulatory measures to promote covered bonds include, for example, Australia, New Zealand, and Canada.

UNDERSTANDING COVERED BONDS

There is no uniformity in the structure of covered bonds—there are reasons why these differences exist. Before we come to the nuances of their structure, let us understand the philosophy behind covered bonds. Corporate bonds, whether secured or unsecured, have the probability of default dictated by that of the issuer. If the issuer defaults, even secured bonds will default, though one may expect a significantly higher recovery rate based on the value of the collateral. Mortgage-backed securities, on the other hand, are presumably structured to insulate the pool of assets from the risk of bankruptcy of the issuer. Mortgage-backed securities typically attain highest ratings on the basis of credit enhancements sized up to absorb the losses of such insulated pool, to an extent that justifies the highest rating.

Covered bonds borrow from securitization framework, as also from the ageold secured bonds. Secured corporate bonds are the obligation of the issuer, and are backed by security interest in the collateral. To what extent this collateral is available in the event of bankruptcy of the issuer, and what are the prioritized or parallel claims on this collateral, is a function of bankruptcy law that differs from country to country. In the case of securitization, the presumption is that the collateral pool will remain completely aloof from the issuer and be unaffected by the bankruptcy of the issuer, thus allowing investors undeterred access to its full value. Covered bonds strike an “approximate” midway by creating a structure that combines at least the following:

• A recourse both against the issuer and the collateral pool, such that, like corporate bonds, the bond is still the obligation of the issuer, yet backed by a claim over a collateral pool that is expected to withstand competing or overriding claims in the event of bankruptcy of the issuer; therefore, there is no complete isolation of the collateral from the issuer as in case of securitization, yet there is a structure that will protect the collateral and preserve it for payment to covered bonds investors on a first-priority basis.

• The presence of credit enhancements that are expected to absorb losses, at a stress level to attain the best ratings, is common in covered bonds too. However, the credit enhancement structures used in covered bonds have traditionally been simpler than they are in securitization.

• Thus, covered bonds lean both on the credit of the issuer as also the strength of the asset pool.

STRUCTURE OF COVERED BONDS

Covered bonds are on–balance sheet securitizations. If by “securitization” is meant the transfer of a pool and its transformation into securities, then covered bonds are not securitization: They are closer to a secured bonds issuance. In a mainstream secured bonds transaction, there is no transfer of the assets to a special-purpose entity (SPE). On the other hand, the assets are identified, and collateral rights are created on the assets as per local secured lending law, and are placed as a security for the bonds. In the event of bankruptcy of the mortgage originator, a general secured lending law or a special law relating to the assets grants the bondholders recourse against the pool of assets, over which security interest had been created. More often than not, there are overriding and parallel claims, arising out of bankruptcy laws or other laws that erode a part of the value of the assets attributable to payment to the secured bondholders. In addition, there would invariably be a disruption in payments to the bondholders, as once the issuer is in distress or bankruptcy, the payments thereafter would only come through the process of legal enforcement of claims over the secured assets. In other words, the secured assets are prone to the bankruptcy risk of the issuer.

Securitization structures intend to eliminate this risk by relying on “true sale”—the asset pool itself is sold using a legally defensible sale, generally to an SPE. The SPE itself is, in legal presumption, bankruptcy remote; that is, it is so structured as to be free from risk of being called into bankruptcy. Thus, securitization transactions may be taken to have insulated the asset pool from the bankruptcy risk of the issuer. That having been done, the only risk to be concerned about is the risk of credit losses in the asset pool. If there are credit enhancements present to absorb that risk to a sufficient degree, the resulting securities may attain highest rating.

The need for securitization structures to depend on isolation or true sale resulted into some consequential features. One of the most significant consequences is the correlation between the cash inflows from the asset pool and the cash outflows to repay investors. This is commonly known as the pass through nature of the transaction, implying that what is received, and whenever it is received, is paid out to investors. The pass-through feature leads to several implications:

• The maturity of the mortgage (or asset) backed securities is the same as that of the asset pool. For example, if the mortgage pool pays off in 20 years, the last dollar to flow to the securities will also take 20 years. There are, of course, several modifiers that come into play; for example, there may be tranches of securities, with some tranches paying before others. There may also be a clean up call option that allows the seller to complete the redemption once outstanding pool value becomes insignificant. However, on a holistic basis, there are no asset/liability mismatches in the transaction—the repayment of the liability, the bonds, is driven by the repayments on the assets.

• As the mortgage loans prepay, the investors get prepaid too. Therefore, the much-discussed prepayment risk gets completely shifted to investors. Once again, reallocation devices that differentially reallocate the prepayment risk to different classes of investors may be used.

• The repayment of the liabilities flows from a static pool. Static pool refers to the mortgages that were there in the pool when it was sold to the SPE. Hence, the mortgage backed securities will be affected by the expected behaviour of a static pool—behavior of key variables, such as prepayment rate, default rate, average rates of return, as a function of time to maturity.

• Since securitization is based on true sale of the asset, questions arise to whether what is sale in law is also a sale in accounting parlance—leading to questions of off–balance sheet treatment of the assets, and if sale treatment is attainable, there is obviously related question of acceleration of the profit/loss and upfront recognition thereof.

Let us now take the case of covered bonds. Given the fact that covered bonds are the obligations of the issuer, they do not have to exactly derive the cash flows from those of the asset pool. In other words, covered bonds are not passed on pass-through cash flows of the asset pool. There may be mismatches (however, within limits as discussed further below) in the cash-flow structure. As such, all the consequential features of securitization depending on the pass-through nature of the transaction can be avoided, or at least mitigated, in the case of covered bonds.

But here comes the key question. If covered bonds are nothing but obligations of the issuer, then what is the difference between secured corporate bonds and covered bonds? As discussed, the genesis of covered bonds lies in giving to the bondholders bankruptcy-proof access to the assets. Hence, covered bonds have to create a legal structure that may allow investors to use the collateral assets, even if the issuer goes into bankruptcy. The basis of this bankruptcy-protected right lies in either a legislation granting them a special privilege, or in the design/structure of the transaction. Accordingly, covered bonds structures, based on nature of jurisdictions, may be classified into legislative covered bonds and structured covered bonds.

Legislative Covered Bonds

A legislative covered bonds structure is one in which a special legislation gives bankruptcy protection to the investors. This goes with the very genesis of covered bonds—they were created to allow investors in the bonds to have the strength of the assets, not just the strength of the issuer. In most European jurisdictions, covered bonds legislations grant a special immunity to the assets backing the covered bonds—that the bankruptcy trustee shall not take over these assets.

Take, for instance, the German pfandbriefe. Under German law, pfandbriefe can be issued only by banks, also on the strength of a specific license issued on satisfaction of several conditions. These pfandbrief issues are expected on a regular and consistent basis, rather than on an opportunistic or sporadic one.

There are several different types of pfandbriefe permitted by the German Pfandbrief Act—mortgage pfandbriefe, public pfandbriefe, ship pfandbriefe, and more recently, aircraft pfandbriefe, each backed by the type of assets that the name implies. Public pfandbriefe are those backed by claims against public sector authorities.

The key feature of pfandbriefe is “covered assets,” the collateral backing up the pfandbriefe. Depending on the type of pfandbriefe, the covered assets should be qualifying mortgages, public sector financial claims or mortgages on ships. In addition, within specific limits, claims against central banks, credit institutions, and derivatives transactions are also recognized as covered assets.

The key to the bankruptcy remoteness of pfandbriefe lies in Sec. 30 of the Pfandbrief Act. This section provides that if insolvency proceedings are opened in respect of the Pfandbrief bank’s assets, the assets recorded in the cover registers shall not be included in the insolvent estate. The claims of the Pfandbrief creditors must be fully satisfied from the assets recorded in the relevant cover register; they shall not be affected by the opening of insolvency proceedings in respect of the Pfandbrief bank’s assets. Pfandbrief creditors shall only participate in the insolvency proceedings to the extent that their claims remain unsatisfied from the covered assets.

There are independent administration provisions for the covered assets. Section 30.2 provides that the court of jurisdiction shall appoint one or two natural persons to act as administrators, whereupon the right to manage and dispose of the covered assets shall be transferred to the administrator. Thus, the administrator either continues to collect cash flows from the assets or dispose it off and pay down investors at once.

Similar provisions exist in other legislations dedicated to covered bonds. Thus, in legislative covered bonds jurisdictions, the protection from the bankruptcy risk of the issuer is attained by special provisions of the legislation.

Structured Covered Bonds

There are several covered bonds jurisdictions that do not have any specific laws to supply the bankruptcy protection. In these countries, issuers have been using a combination of SPEs and a transfer of the assets, presumably to attain bankruptcy proofing. These may be called structured covered bonds jurisdictions.

The parties involved in a structured covered bond are

• Originator: the bank/entity that wanted to raise funding.

• SPE: the special purpose entity that is interposed in the picture, to hold legal title over the pool of assets and provide bankruptcy protection. The SPE should be so structured as to be free from the risk of consolidation with the originator.

• Cover pool monitor: an entity to ensure that the cover pool satisfies the minimum credit enhancement required by the transaction.

• Administrator or trustee: an entity that will take over the assets in the event of bankruptcy of the originator.

• Bond investors.

A typical structure of a structured covered bond is shown in Exhibit 22–1. The mechanics of a typical structured bond can be described in the following steps:

EXHIBIT 22–1

Structure of Structured Covered Bonds

• Step 1: A structured covered bond typically has an independent SPE that holds title to the assets or the cover pool. Note the significant difference—in normal securitization structures, the bonds are issued by the SPE. In case of structured covered bonds, while the collateral or cover pool is legally sold to the SPE, the issue of bonds is done by the originator or the bank that wanted to raise funding. Hence, the bonds are the direct and unconditional obligation of the originator. The bonds are usually unsecured obligations of originator, as security interest is created by the SPE (see next). The role of the SPE is to provide a secondary recourse. Hence, in structured covered bonds, the SPE is typically a guarantor.

• Step 2: The proceeds raised through the issue of covered bonds will be on-lent to the SPE. In turn, the SPE uses these proceeds to purchase from the originator the cover pool on a true sale basis.1 Thus, the SPE becomes the legal owner of the pool. In other words, from a legal perspective, the sale from the originator to the SPE must satisfy the legal features of a true sale. The sale, however, is not a sale from accounting viewpoint—see the discussion that follows. Also, note that the loan given by the originator to the SPE is subordinated to the obligations of the SPE to the bondholders.

• Step 3: Backed by the cover pool, the SPE provides a guarantee to covered bondholders for the payment of interest and principal on the covered bonds, which becomes enforceable if the issuer defaults. The guarantee represents an irrevocable, direct, and unconditional obligation of the SPE and is secured by the cover pool. That is, the SPE creates a security interest on the collateral pool in favor of the trustees.

• Step 4: The originator continues to collect and service the cash flows from the mortgage loans. As there is a mismatch between the payments from the mortgage pool and the payments on the bonds, the originator is allowed to (a) retain the collections from the pool; and (b) make payments toward the bonds in excess of collections from the pool. In legal sense, the originator having sold the collateral pool to the SPE now becomes the servicer. However, the cash flows collected from the collateral pool, after external expenses, are allowed to be retained by the originator as repayment of the inter-company loan given by originator to SPE. Thus, as the originator would have collected cash from the collateral pool, the inter-company loan and the purchase of assets by the SPE are squared off; that is, the SPE’s obligation to repay the inter-company loan is taken to have been satisfied. On the other hand, as the covered bonds are the direct obligations of the originator, the same may be repaid by the originator periodically.

• Step 5: Although the originator holds the collateral pool and may use the collateral pool’s cash flows, and may replace assets in the collateral pool or add new assets in place of those amortized or prepaid, the originator needs to ensure that the credit enhancement levels are maintained at all times. Usually, an independent cover pool monitor monitors the compliance with this requirement.

• Step 6: While the originator may add further loans to the collateral pool, or withdraw loans from the pool, the aggregate amount of collateral “sold” to the SPE must have a minimum amount of credit enhancement.

• Step 7: If originator bankruptcy event takes place, the SPE’s guarantee to the bondholders kicks in. At this stage, the SPE attaches the collateral lying with the originator, and passes it on to the administrator.

• Step 8: The claims of the bondholders are paid from the cover assets. In case of a deficiency, the bondholders will have an unsecured receivable from the issuer.

COVER ASSETS AND CREDIT ENHANCEMENTS

Because covered bonds rely both on the asset pool and originator credit, it is important to ensure that the credit risk of the asset pool is absorbed by credit enhancements. While securitization transactions have used a variety of forms of credit enhancements, covered bonds have traditionally used over-collateralization. That is to say, the originator needs to ensure that the “cover” assets over-collateralize the outstanding bonds by the required minimum degree of over-collateralization. For example, if the required over-collateralization is 10%, for outstanding bonds of $100, there need to be covered assets of at least $110. As the bonds are amortized over time, this over-collateralization ratio has to be maintained at all times.

In addition to this, the cover assets, that is, assets forming part of the cover pool, must also satisfy certain features laid down by either legislation or regulation, for example, the loan-to-value ratio in case of each loan. In other words, the quality of the underlying loans in the cover pool is carefully guarded by regulators.

ASSET/LIABILITY MISMATCHES AND LIQUIDITY RISK

Covered bonds are repaid independent of the cash flows of the cover pool. So, they are paid from the regular cash flows of the originator. Likewise, the cash flows received from the asset pool go and become part of the regular cash flows of the cover pool. This clearly implies an asset/liability mismatch underlying a covered bond.

If this asset/liability mismatch was completely uncontrolled, then the obligation to repay covered bonds would have been no different from an obligation to repay any secured or unsecured bond issued by the originator. Hence, the strength of a covered bond depends on how wide is the asset/liability mismatch. The asset/liability mismatch reflects the liquidity risk of the transaction. If the asset/liability mismatch is too wide, a covered bond leans too heavily on the liquidity strengths of the issuer, and therefore is no different from corporate bonds. If the asset/liability mismatch is negligible, a covered bond leans towards being a mortgage-backed security. Hence, usually, covered bonds issuers keep the asset/liability mismatch under control. The extent of asset/liability mismatch also affects the likely rating upliftment that a covered bond may receive, as discussed below.

Exhibit 22–2 shows a computation of the asset/liability mismatch done by rating agency Standard & Poor’s. In this exhibit, column A shows the likely balances in the asset pool, and column B shows the likely balances outstanding of the covered bonds. As one may notice, at the inception, the cover pool value is $120, while the bonds outstanding add to $100, implying an over-collateralization of 20%. There is a mismatch between Column A and Column B, as is apparent. The outstanding balances of the assets are based on the amortization of the mortgage loans, incorporating assumptions of prepayment and default. The outstanding balances of the bonds in column B are based on the contracted repayment of the bonds. This may be seen in column D. It may also be noted that while the asset pool will take several years to fully pay down, the bonds are scheduled to be fully paid down at the end of 10 years.

EXHIBIT 22–2

Computation of Asset/Liability Mismatch in Covered Bonds (S&P)

The gap between the cash inflows and outflows is given in column E. Column F applies a scaling factor, giving more weight to a mismatch in earlier years and less to those in later years. The scaling factor is array of scales used by the rating agency in question.

Finally, in column G we accumulate the asset/liability mismatches, and find the highest level of mismatch. This is defined as the asset/liability mismatch of the transaction. The greater the mismatch, the greater is the transaction’s dependence on the issuer’s rating.

With the discussion above on asset/liability mismatches, it would be apparent that the maturity of covered bonds may be unconnected with the repayment of the assets. Usually, covered bonds may have soft bullet maturity; that is, they have an indicative payment date, but the issuer is allowed an extension of time to repay the bonds after maturity. In the example, column D shows payments to the bonds in five different years. This would most likely not be five payment dates on a single bond, but five different tranches of bonds with single bullet maturity dates each.

RATINGS OF COVERED BONDS

As we have discussed earlier, the desire of a covered bond issuer is to raise funding by an instrument that pierces the rating of the issuer. That is, rating upliftment is a significant objective of every issuer.

All the major rating agencies have come up with criteria to give ratings, in fact, rating enhancements to covered bonds transactions. These criteria have been evolving over time, and as volatility spikes occur within the financial system, rating agencies become more conservative.

We do not intend to discuss the rating criteria of each of the agencies here, but we need to observe that unlike in case of securitization, ratings of covered bonds are not completely detached from the rating of the issuer. In fact, the issuer’s rating significantly controls the ratings of covered bonds. Hence, rating agencies typically lay down a matrix of factors, on consideration of which they will notch-up the rating of the covered bonds by specified level of notches.

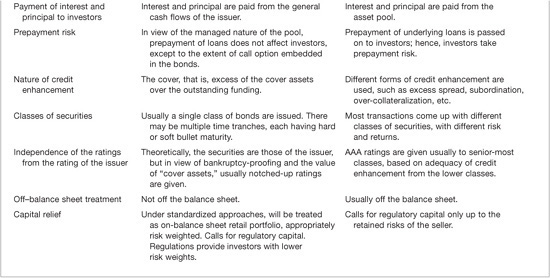

COVERED BONDS AND SECURITIZATION

As we have stated, covered bonds are though historically grounded into secured bonds, but in the recent past transactions have been enriched by securitization methodology, particularly in countries that do not have specific covered bonds legislation. Hence, they are a hybrid between securitization and secured bonds. The few points of similarity between the two are: both result into creation of securities; both are methods of funding from the capital markets; both involve creation of a pool of assets; both have trustees overseeing the implementation of the transaction covenants, etc. The structure of covered bonds would look very similar to the master trust structure of securitization, particularly if the structure is used in case of residential mortgages. However, there are significant points of dissimilarity, as shown in Exhibit 22–3.

EXHIBIT 22–3

Covered Bonds and Securitization Compared

ACCOUNTING FOR COVERED BONDS

Looking at the structure of covered bonds, particularly in case of structured covered bonds, one may notice the presence of a legal transfer of the cover assets from the issuer to the SPE. Would this have the impact of removing the cover assets from the books of the seller-issuer? Under IAS 39/FAS 140, true sale is not a precondition for off–balance sheet treatment. Transactions that qualify as pass-through arrangements, even if not backed by true sale, may lead to assets being off the balance sheet. Neither does true sale guarantee an off–balance sheet treatment. On the other hand, off–balance sheet treatment is based on the substance of the transaction, that is, risks and rewards from the asset pool. If the seller retains significant risks and rewards, the asset continues to be on the books of the seller, and the funding raised is treated akin to a borrowing.

As we have discussed, several covered bonds transactions rely on true sale to achieve bankruptcy protection. Hence, a question may arise—as the originator sells the pool to an SPE that guarantees the repayment of the bonds, should the assets go off the balance sheet of the issuer? The answer would be clearly no, because the bonds are an unconditional obligation of the issuer. Hence, the making of the true sale does not put the assets off the balance sheet of the issuer.

Accounting rules also provide that what is not off the balance sheet of the seller cannot be on the balance sheet of the buyer. In case of structured covered bonds, the SPE is the buyer and guarantor of the bonds. However, the SPE cannot put the assets on its balance sheet. If the SPE prepares any balance sheet as per accounting standards, it may have to make disclosure of the liability on account of guarantee, but neither the asset nor the loan will as such come as on-balance sheet items for the SPE.

KEY POINTS

• As a capital market device for refinancing mortgages, covered bonds have existed in continental Europe for more than 200 years. However, their recent popularity seems to be emanating from the unpopularity of mortgage-backed securities following the subprime crisis.

• Covered bonds may be viewed as a hybrid between corporate bonds and mortgage-backed securities—in the sense that they are an obligation of the issuer, they are close to secured bonds, but since investors also rely on the assets as a backup, they have features of asset-backed securities.

• The asset-backing in form of cover assets provides dual recourse to investors. How clear is the ability of investors to rely on the assets, immune from the post-bankruptcy claims of other creditors, depends either on the legislation, or the legal structure of the transaction.

• Where the bankruptcy protection comes from legislation, it is called legislative covered bonds; where it comes from the legal structure, it is called structured covered bonds.

• Structured covered bonds use a special purpose entity that agrees to buy the cover assets, albeit with funding provided by the issuer. The SPE then guarantees the repayment of the bonds.

• The key idea of covered bonds is to provide a rating upliftment, so that the bonds are able to achieve a better rating than that of the issuer. The notches by which rating of covered bonds may go up above the rating of the issuer are based on the quality of the cover asset, extent of credit enhancement, inherent asset/liability mismatch and liquidity risk, etc.

• Credit enhancements in case of cover bonds are mostly in form of overcollateralization.

• While structured covered bond transactions make use of the device of sale of the cover pool by the issuer to an SPE, the sale is done such that it qualifies to be a legal sale but not a sale in terms of accounting standards. Hence, from an accounting viewpoint, covered bonds are not different from secured bonds.