CHAPTER 2

Lead through Influence

Establish context across your organization and communicate effectively with stakeholders.

What you’ll learn in this chapter

1 What’s meant by the (often misunderstood) term “leading (or managing) through influence” and how you can apply it.

2 Powerful but simple techniques to help you develop strong relationships with stakeholders across your organization.

3 How to avoid common communication pitfalls that can undermine your effectiveness when working with senior management.

What Is Leading through Influence?

Product managers are in a catch-22 situation. They are expected to be strong leaders, respected across an organization. They must deliver outstanding products that drive business results. They do so by leveraging the talents of a cross-functional group of people—individuals with their own personal, professional, and business objectives to consider. Product managers take responsibility should something not work out, yet they are liberal in praise for the efforts of others when they do.

As a product manager, however, you have no direct authority over those you depend on—a team that will include engineers, designers, marketers, product support personnel, executives, and more. None of them report to you, and they may be more experienced or senior, or of longer tenure.

To achieve your goals, you will need to rely on persuasive power, not positional power. (See Figure 2.1.) Your role is independent of and central to the organization’s goals, yet it is dependent on the success of others. Far from being a handicap, this can make you more effective. You are more likely to be seen as impartial. Rather than instruct and direct your team, you will rely on

• objectivity and data to drive decision-making,

• cross-team collaboration and compromise to deliver outcomes, and

• the needs of the customer and business to guide your priorities.

FIGURE 2.1 The difference is clear

Leading through influence is a subtle but essential skill to master if you are to be successful. For others to willingly follow your lead, they must trust you, fully believing in the purpose behind your actions.

Product managers are careful to ensure their motivations are best for the customer first, company second, team third, and themselves last.

That’s not to say that leading through influence works every time—far from it. Product managers can still be hamstrung by politics, dependencies on resources they have no control over, and others’ irrational behavior.

Stay clear of office politics and you’ll preserve your relationships and reputation. Resist resorting to manipulation: it’s a quick way to kill your career. That doesn’t mean you should let someone walk all over you. If you’re having trouble with someone, provide them honest, open, constructive feedback (if they are open to it), and do your best to work through or around the issues.

Using Positional Power Rather Than Influence

In one of my first product management roles, I was tasked by a C-level executive to lead an important and urgent initiative. He asked me to get a team assembled to work on it right away. Ambitious and hungry for leadership opportunities, I readily agreed.

I called a meeting together, including people from the marketing, engineering, and design teams. I gave a rousing speech, asking that they drop what they were doing and commit themselves to this new goal—as it was of great importance to the C-suite.

Distressed by the urgency of this new priority, the team reluctantly agreed to switch gears and focus on what had been asked of them.

A few days later, the C-level executive approached me and asked to speak in private—he was visibly angry. He proceeded to explain that several team members had come to him to complain that I had steamrollered them into working on this new initiative.

I protested. “But you asked me to. This is something you want, isn’t it?”

“Yes, I want this, but no, I didn’t ask you to operate that way,” he replied. “Instead of pushing them into doing something, I wanted you to motivate them. You should have explained why it was important—provide business context and discuss the customer need. Just because I want it and asked you to lead it, doesn’t mean you can suddenly direct others. You used my position and my seniority to transfer authority to yourself. That weakens me. I want to inspire my team, not simply order them to work on something.”

I was shocked and will never forget that lesson.

Sometimes leading through influence is called “managing by influence.” While they mean the same thing, I prefer “leading” since, strictly speaking, you aren’t managing others.

You may well think the advice and techniques outlined in this chapter are just common sense—and you would be right. However, you’d be surprised how little product managers and other professionals remind themselves every day to make use of these influencing techniques—to their own detriment. Instead, they focus on only those techniques that are expedient in achieving short-term goals. However, with deliberate action, you can put them into everyday practice, helping you build strong, lasting professional relationships, become more effective in your career, and have greater impact on your organization.

How to Lead through Influence

Essentially, influence is at its most effective when you see it primarily as creating the context in which everyone understands and shares an appreciation of the same goals, data, approach, and constraints—and their unique contribution but interdependent roles—in pursuing the vision.

Context describes the underlying reasons that guide a specific course of action or direction. It is “why” you are doing something, not “what” or “how.”

Inexperienced product managers can be prescriptive on the “what” and “how” but not provide enough of the “why.” That’s a problem: teams that don’t understand or don’t believe in the “why” tend to be unmotivated, even rebellious. They don’t feel connected to or valued by the business. They aren’t convinced that they are working on something useful to the business or to customers.

By setting context, others will more often than not reach similar insights as you. Be patient and share, in detail, the bigger picture and all of your supporting data. Ask them open-ended questions, without directing them to your conclusions. Ask them to voice their thoughts and reach their own conclusions about what needs doing—perhaps they will surprise you with new perspectives or something you missed. And you’ll get a more motivated team.

Here are actionable techniques you can employ to set context in your daily work environment. Use them repeatedly, and over time you’ll increase your ability to persuade others, and persuade them with conviction.

1. Constantly Reinforce Product Vision, Strategy, and Business Goals

Don’t assume that everyone understands and appreciates the desired outcomes. For any initiative, this can be true at any time, but especially when

• you’re introducing a new, possibly daunting and vague concept;

• everyone is heads-down, hard at work in the trenches executing against the plan; or

• the first data, bugs, and change-requests start coming in after launch.

Losing sight of the underlying purpose is easy. Despite your best efforts, the objectives might not be well understood by all. Likewise, business goals frequently change, typically quarterly, but sometimes suddenly. Your team might feel disconnected, unsure of how what they are doing fits in.

As opportunities arise, remind your team of the “why” behind what they are doing. Link every product initiative to a central goal of the business, ideally with a measurable target. Periodically revisit your progress toward the goal and share the results.

2. Introduce Change and Constraints Clearly—and Appeal to the Team to Creatively Work through Challenges

Change is inevitable. It may be that business performance is off-track or you’ve discovered something during product testing that requires a reset. Or decision-makers set a new priority or reallocate resources away from your product. You may or may not understand and support these changes. And even when you do, the rationale may not be evident to others. Seek clarity as to why the changes are needed, consider what adjustments you’ll need to make, and share the underlying causes with your team.

Give control back to your team to whatever extent possible. Work with your team to develop a new path forward—don’t prescribe an answer. Allowing them to solve the problem and take ownership means they’re less likely to feel powerless or like victims of change.

Regardless of your true feelings, never complain about management in an attempt to sympathize with the team. This creates a “them” and “us” mentality and is terribly unproductive and unhealthy.

Similarly, every team believes they could achieve so much more if only they had more time and resources. They believe they’d be more productive if they didn’t have to contend with attending meetings, addressing emails, training new team members, fixing bugs, writing documentation, creating work estimates, or communicating updates to others outside the team. You may even be tempted to join in with your team in complaining about all these limitations. But every business has constraints, especially with allocating scarce resources across competing priorities. Help your team understand constraints, appreciate the value of the perceived overhead activities, and find constructive ways to work within the limits.

3. Liberally Gather and Share Quantitative and Qualitative Data—Demonstrate You Are Objective and Impartial

It might surprise you to know how many strategic discussions are based on opinion alone. But even the most experienced expert isn’t going to be right all the time. And as product managers lack direct authority, it’s rare they win a debate solely on opinion. Just because you’re charged with making prioritization decisions for your product doesn’t mean you can make decisions based on your own “expertise.”

Rather than simply present and argue for your opinion, arm yourself with persuasive, supporting data—quantitative and qualitative. Likewise, when stakeholders present choices that seem based on opinion alone, listen to different points of view, and ask yourself what data you need to validate or invalidate them. Remain objective and open to being challenged. Do not react emotionally. Keep your ego and personal goals in check. By introducing the relevant data into the conversation and presenting a compelling case, you can effectively align others behind a course of action.

But you’ll need to be prepared with more than just the top-line data points. You will also need to prepare the following:

• Different levels of detail—Don’t overwhelm your audience with complex reports and tables with too many data. Conversely, don’t show data at such a high level that it limits discussion and understanding of the details when needed. The trick is having multiple levels of data ready—summaries, with more detail on hand to support your position if questions come up.

• Methodology—Understand how the data has been collected, have confidence in its accuracy, and be able to explain where the flaws might be. Your data will only be persuasive if you can defend its validity and eliminate your own biases. Common issues include the following:

![]() Overuse of averages or canned reports from analytics tools (hiding trends within segments and distributional patterns).

Overuse of averages or canned reports from analytics tools (hiding trends within segments and distributional patterns).

![]() Selecting data trends that are unduly influenced by external factors or edge cases (not under a product manager’s control).

Selecting data trends that are unduly influenced by external factors or edge cases (not under a product manager’s control).

![]() Difficult-to-reproduce data or results extrapolated on too few data points (such as relying on input from only one or two customers).

Difficult-to-reproduce data or results extrapolated on too few data points (such as relying on input from only one or two customers).

![]() Confusing correlation with causation (therefore jumping to conclusions about what product improvements will bring).

Confusing correlation with causation (therefore jumping to conclusions about what product improvements will bring).

![]() Lack of a common definition among stakeholders (leading to different interpretations of the same data).

Lack of a common definition among stakeholders (leading to different interpretations of the same data).

• Insights and recommendations—Don’t present a raft of remarkable data but leave your audience not knowing the implications. Be prepared with a “so-what”: a set of actionable insights that draw conclusions from the data and a set of recommendations for proceeding. Stakeholders will want to discuss the implications and next steps. Come ready with your plan.

The most potent source of data you can gather and present is the voice of the customer. You must be the customer’s advocate—validate that the decision is in their best interests. Speak up, if not. With many different roles and departmental goals, it can be easy to lose focus on the customer and get caught up in internal challenges or over-optimize for short-term business outcomes.

![]() In Chapter 11, I share best practices for developing useful metrics, and in Chapter 5, I discuss techniques for gathering customer data to inform product decisions.

In Chapter 11, I share best practices for developing useful metrics, and in Chapter 5, I discuss techniques for gathering customer data to inform product decisions.

Gather and share customer testimonials and unfettered feedback. Few things are more powerful at motivating a team than hearing the customer speak to them in their own words. Don’t seek only positive feedback, but don’t overwhelm them with too much negative feedback either. Find a balance to generate motivation and optimism while identifying constructive improvements.

4. Create Opportunities for Stakeholder Involvement and Open Discussion

Senior stakeholders love to feel useful. Figure out ways to recruit them in your efforts. You might use them as sounding boards or involve them in problem-solving sessions. You might want their help in getting the support of their teams or have them boost morale by reaching out and thanking hardworking team members. The more they feel involved, the more they’ll provide support.

Effective Leading through Influence Tactics

REINFORCING GOALS

• Put your product vision, Objectives and Key Results (OKRs), and roadmap up on the wall where they are highly visible. Be sure to avoid ambiguous, wordy vision statements, however well-intended—otherwise you’ll invite cynical eye-rolls.

• Ask your team to describe where they think their work fits into company priorities. Discuss and clarify their responses to help them see their work’s relevance and impact.

• Hold occasional offsite sessions to discuss team progress toward the product vision. Invite them to participate in brainstorms and provide feedback on ideas, priorities, and process improvement. Allow the conversation to become critical, so long as it remains constructive.

• To the extent you can share results publicly, regularly update your team on key business metrics and product KPIs. Display them on a TV screen, clip them from reports, and send in emails—or set aside time every other week for team review.

SHARING THE VOICE OF THE CUSTOMER

• Ask the customer service team to send you a selection of incoming emails or call records about your product. Share these with your team, providing your own editorial overview. Ask customer service to select specific, actionable messages, both positive and negative. “Good job” isn’t as effective as “Thank you for launching the updated dashboard—now I can find everything in one place.”

• In each customer interview or user survey, ask users for a personal story of how the product has impacted them. You may get some deeply moving, highly compelling stories to share.

• Take a team member with you on customer interviews so they can hear firsthand accounts of both enjoyment in and struggles with your product. These experiences are more likely to generate empathy and drive home critical insights than your secondhand messages. Rotate your team through multiple interview sessions so you don’t have too many people attending each session, which can overwhelm the interviewee.

INTRODUCING CHANGE AND CONSTRAINTS

• When introducing any change, always start by giving the rationale that drove the outcome. Here are some examples:

“Last month we set a goal to increase user engagement by 10 percent, but we fell behind; therefore,...”

“After testing the product with customers, we received feedback that the current feature is confusing; therefore,...”

“At last week’s product-review meeting, we reprioritized X higher than Y because...; therefore,...”

• When something changes, don’t immediately prescribe the new path you want to take. Instead, communicate the context and rationale to your team and ask them to share their observations and identify possible solutions. Often, they will arrive at the same conclusions as you will, but they will be far more committed to the new approach.

• Understand what other people in your company are working on. Share the value of the contribution of all competing priorities (the overall portfolio) with your team.

• Discuss the value of, and opportunities to improve, “overhead” activities. For instance, regular email communication and update meetings drive support and minimize disruptions, training others spreads the workload, setting milestones provides clear goals and alignment, and bug fixes reduce tech debt.

ENGAGING STAKEHOLDERS

• Ask a senior executive to swing by to chat with the team about the importance of the project the team is working on, focusing on the business results the executive hopes to deliver.

• Ask your team to suggest any questions they have for management regarding quarterly business goals and where your project fits in. Find an appropriate forum to ask these in—such as in emails or in all-hands or weekly meetings.

• Ask whether your team feels comfortable with your sharing their concerns over business goals, process, or culture (anonymously) with management, and promise to come back to the team to discuss management’s perspectives.

• Never propose taking team members from another project to increase those working on yours, without understanding the relative impact on other priorities. Instead, discuss the idea with stakeholders and project leaders who will be affected before you make any formal proposal.

A little secret: stakeholders, even executives, are often misaligned with each other. They are too busy, too focused on achieving their specific goals, and too harried by their responsibilities. They haven’t had the time to identify all the cross-department issues and hash them out. These issues, if left unresolved, can impact product quality, timelines, and customer value.

Sometimes influencing merely requires you to get a group to meet to tackle a tough blocking issue. Get key stakeholders into a room and set a clear agenda for discussion. First, you structure the discussion, explaining the problem and sharing all the data you have. Then you can sit back and let them talk. About halfway through, ask a couple of probing questions and suggest possible courses of action. Often, everyone in the room has already reached the same conclusions, but now they feel involved and committed to solving the problem.

Stakeholder Discussion and Finding Compromise

Our company was attempting an international launch. We had tried twice before but had been delayed due to resource issues and last-minute priority changes. While we had agreed on the need to grow internationally, the strategy wasn’t clear, and the execution plan was cumbersome. The project would have taken three years to deliver.

The key stakeholders—the head of international, the CTO, the CEO, and the CFO—were all highly frustrated. It felt like we were trying to do too much at once. I wondered if there might be a compromise.

I first worked with the head of international to understand his business goals, explore different business models, and prioritize high-value clients. I discovered that 80 percent of the revenue opportunity would come from one industry segment, but he was being held to a higher target requiring much more complex product solutions to serve many segments.

I then worked with development leadership to explore reducing the scope and determine resource requirements. The aim was to dramatically speed the time-to-market (from 3 years to 12 months). Finally, I worked with the CFO’s team to put together a revised budget (much lower than before), which implied setting new revenue goals in keeping with the reduced scope.

After understanding each stakeholder’s goals and needs, I called a discussion, putting on the table all the options, points of view, and recommendations for focus and reduced resourcing levels. After much debate on the pros and cons, everyone agreed the new option was the right balance between reducing scope and achieving revenue targets. The plan was adopted, and the stakeholders committed to and owned the new approach.

While scheduling stakeholders to meet might be a challenge, attempting to resolve a complex issue over email is ineffective and can quickly spiral out of control as misinterpretations start to stack up. Likewise, trying to fix a problem in a series of one-on-one meetings usually leaves you playing the role of go-between. All that back and forth is very inefficient, and confusion is likely.

Managing Up: Working with Senior Stakeholders

Contrary to what it sounds like, managing up does not mean you manage your manager. Managing up means understanding and preempting your manager’s needs (and the needs of other key decision-makers), providing information proactively, and seeking guidance from others when needed (while also respecting their time). Influential product managers—like all good employees—look to make their manager, other stakeholders, and the overall business successful. When you do so, you build trust and confidence in yourself and your direction.

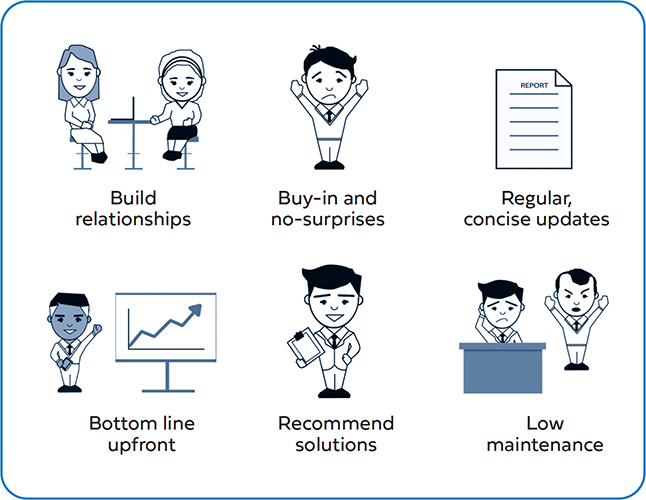

By regularly practicing the following six principles, as illustrated in Figure 2.2, you can master managing up.

FIGURE 2.2 Managing-up techniques

1. Build Relationships before You Need Them

Build strong rapport with your direct manager, other senior stakeholders, and team members long before you need their assistance. If you leave it until you need their help, they may be less inclined to expend their own time and political capital in assisting you.

Start with identifying your stakeholders. Think broadly—don’t limit your thinking to those with whom you work directly or those who are more senior to you. Consider peers and trusted independent contributors too. Anyone who is a decision-maker or influencer providing support or input on your product should be on your list. If you can, get a copy of your organizational chart. Traverse through each function to ensure your list is complete.

Here are some questions that will help you identify stakeholders:

• Who guides my work and career? Your manager (obviously), but also your manager’s manager. A word of caution: be open with your manager about any “skip-level” conversations you plan to have before you have them and always demonstrate commitment and support for your manager during those discussions.

• Who else guides or decides priorities that affect my product? This may include business leads, colleagues charged with strategic planning, and anyone who approves investments.

• Who guides or decides resourcing for my projects? The leaders to whom your engineering, QA, and design team members report. Be liberal with positive praise for your team’s work ethic, capabilities, and results, while being honest and sincere about challenges you collectively face.

• Who keeps the trains running on time? Members of project management, release engineering, and technical operations teams who manage the development process, handle timelines and dependencies, and support in-production software. When something unexpected happens, you want them on your side.

• Who has access to data I might need? Analytics, consumer insights groups, or market research groups can provide reports, dig up data, validate your assumptions, or conduct quick-and-dirty analyses to help you make decisions. Usually, they are in high demand and are overworked.

• Who sells to potential customers? Sales and marketing. When you wish to speak to customers, it’s essential you have a supporter who will connect you and trust you to handle those conversations diplomatically.

• Who else talks to users regularly? Don’t overlook your customer success teams (such as account management or customer service). They often know more about customer issues than anyone. They’re usually delighted to be asked to contribute to share insights on what they hear every day from the field.

• Who are the most trusted and respected independent contributors? Look for long-term employees and individual contributors who are frequently invited to participate in strategic discussions—or for seasoned engineering leads who can come up with creative solutions to otherwise technically challenging problems. Seek their input and appreciate their access to strong, informal internal networks.

• Who might be a good role model or mentor? Consider senior product managers or experienced people managers outside of those you report to. They are often open to coaching you or acting as a sounding board. Most are flattered to be asked and, as they aren’t part of your chain of command, are an excellent “low-risk” source for constructive feedback.

• Who addresses everyday challenges? Support staff such as executive assistants, front-desk people, human resources employees and recruiters, and the IT help desk. Share your project goals with them, and engage with them where possible. If they understand your goals, they can expedite the little things, whether that’s scheduling last-minute meetings, quickly resolving IT issues, or ordering lunch as a reward for your hardworking team.

Before your first meeting with a stakeholder, put yourself in their shoes. Although there are company goals, each stakeholder has their own goals to meet, and those other goals may well conflict with your desired course of action. Ask yourself the following:

• What goals and incentives do they have and how might my goals be aligned or in conflict with theirs?

• Do they know what I’m working on for the business? What concerns or questions might they raise?

• What needs do they have that I haven’t considered yet? What product feedback can I gather from them?

• How will they and their team benefit (or not) from my plan of action?

• What commitment and support can I ask them to provide?

As you meet with each stakeholder for the first time, here are some fundamental questions to ask them:

• What are your key goals (and how are these measured)?

• What does your team do to achieve these priorities?

• How can I help you achieve your goals?

• What data, resources, or relationships do you have access to that will give me the information I need to promote, prioritize, and address your needs?

• How best can I work with you and your team? What has worked well or not so well in the past?

• What do you like or dislike about my product?

• What more do you wish it could do? (When you respond to their wish list, make promises only if you can keep them.)

• How, and how frequently, would you like me to keep you updated on my initiatives?

• Who else on your team should I meet with?

Finally, consider their preferred communication styles and determine how to keep in regular contact with them:

• Do they prefer email updates or in-person dialog?

• Do they want regular, scheduled one-on-one meetings, or catch-up only as needed?

• Do they want time to process new information before responding, or do they prefer to jump into problem-solving mode—such as whiteboarding—immediately?

• Are they “water-cooler” types, preferring informal discussions where you bat around ideas? Or do they prefer short, formal meetings with clear agendas, where you quickly get down to business and make clear-cut decisions?

Don’t expect all stakeholders to be able to dedicate much time to you. However, most should be willing to at least grab a coffee and chat with you for 20 minutes or so. Come ready with questions and let them do the talking.

Always discuss these meetings with your direct manager, ask for their permission, and invite them (at their option) to meetings with anyone more senior than they are—especially their direct manager. It’s both courteous and a sound practice to keep them in the loop.

Also consider the importance of informal relationships. While personal commitments outside of work, or culture and beliefs may limit your involvement in some activities, go out to lunch, hang out after work, participate in the happy hours or office parties, join the sports team, or volunteer for the social committee. Express authentic interest in others in conversations. The more you know everyone at deeper levels, the more trust builds and the easier it gets.

Don’t think that building relationships is “sucking up” or means you have to sugarcoat your communications. Superficial relationships quickly crumble when under stress. Building a relationship is about finding common ground—a mutual passion for the company’s mission or shared personal values—and developing a deep respect for each other’s contributions and complementary talents. You don’t need to be the best of friends, but you do need to move beyond simple professional courtesy.

2. Seek Buy-In and Practice a No-Surprises Policy

Influential product managers master the techniques for getting buy-in across a large group of stakeholders. Buy-in is a process through which you “prewire” group consensus by previewing key points individually with stakeholders, ahead of a group discussion. It gives them a chance to digest the information and to respond and get onside with your recommendations. It reduces the likelihood of negative reactions and forewarns you of issues that might derail you when meeting in a larger group.

If you learn something that may be important for stakeholders to know, proactively share it with them, even when doing so is uncomfortable for you. Don’t let them be surprised to hear about an issue for the first time in a meeting or from someone else in the organization. Likewise, never present controversial data or recommendations in a group setting where they are seeing it for the first time. Not only do you risk causing a commotion, but you miss a golden opportunity of giving them time to come around to your thinking and speak in support of your challenging new insights.

The perfect meeting is one where you know you have consensus on your desired outcomes with stakeholders and you receive unanimous public support. Buy-in increases the chance of that happening. A group meeting still enables everyone to share perspectives and debate, and you may yet have unexpected outcomes should the group uncover additional implications. But it’s less likely a single stakeholder will express surprise or strongly disagree with you.

When seeking buy-in, consider stakeholder “hot buttons,” and adapt your message and delivery to their preferred style. Consider the following, for example:

• Are they highly analytical, detailed-oriented, or data-driven (finance people, business leads, data scientists)?

• Are they visionary, brand-sensitive, and long-term thinkers (founders, CEOs, CMOs)?

• Are they determined to ensure time for thoughtful planning, execution, and quality (project managers, engineers, technical operations people)?

The Value of Buy-In

My meeting with the VP of operations was going to be tough.

There had been no progress on some of his workflow automation goals for over a year. His team’s processes remained very manual and time-intensive. But other initiatives were always justifiably higher in priority. We would save a few hundred thousand dollars per year in costs, sure, but other projects with similar engineering effort could generate ten times that amount in revenue.

The latest roadmap did not address many of his needs. Knowing he would object, I asked to meet before its presentation. I planned to share what I was going to recommend and get his input. Over lunch, I told him I couldn’t see a way to prioritize his initiatives. I reiterated his pain points (showing empathy) and acknowledged that he’d been promised commitments (by others) at previous planning sessions that still would not be delivered.

He was disappointed and argued for some time—even getting emotional at times (he was obviously frustrated). I presented data to show the value of other priorities while reiterating my appreciation for his position.

By the end of our meeting, he’d accepted the outcome and agreed these were the right decisions. He also made it clear that he’d still bring up his objections in the group meeting so everyone understood the issue—but signaled he would support the roadmap. Which he did.

He also thanked me... expressing gratitude for hearing him out. We met regularly after that, treating each other with renewed trust and respect.

• Are they concerned with how customers will respond and how the company will hit revenue targets (sales reps, marketing people, customer success/support employees)?

When you know what’s important to each stakeholder, you can customize your message accordingly.

3. Proactively Deliver Regular, Concise Updates

To a stakeholder, no news might be bad news. Don’t wait for stakeholders to follow up with you to get the latest update—give them one less thing to worry about by updating them proactively. An email, sent mid-Friday afternoon, is both a suitable medium and time—in just a few minutes at the end of the week, recipients can read it and respond (or peruse it on Sunday evening before the week starts).

Make updates concise—no more than a couple of paragraphs (or, better yet, outlined using brief bullet points) and well under one page. Only you care how you and your team spent every hour this week. And while there are always hundreds of small wins and completed tasks, they aren’t all weighty enough that stakeholders need to know about them.

Long emails will not be read. Recipients should be able to glean key points at a glance. (Confirm with recipients that they are indeed finding them useful.)

Stick to a couple of key points such as these:

• What were your notable achievements this week? (And how are they aligned with progress towards your goals)?

• What are your priorities next week?

• What are the significant upcoming milestones and dates in the next month and beyond?

• What are the challenges, issues, obstacles, concerns, and outstanding action items inhibiting your progress?

• What specific action items do you want your managers or other leaders to take?

• What interesting data can you share (customer testimonials, charts, research, relevant articles)?

• Who on your team should you call out (for going above and beyond), and precisely what did they do?

As with the buy-in process, don’t surprise anyone with an unexpected, bad-news update late in the week, just when everyone is ramping down.

Done well, product updates by email are excellent for keeping stakeholders feeling confident and in the loop, while allowing you to promote the value of your product initiatives.

In addition to a regular email, schedule a one-on-one meeting with your direct manager for about 30 minutes each week (or longer, or more or less often if they desire). Instead of expecting them to run the meeting, send an agenda ahead of time and come prepared with talking points.

Your purpose is to build confidence by

• providing a status update,

• asking questions and seeking feedback,

• clarifying and aligning business priorities,

• engaging your manager in your problem-solving, and

• asking for specific support where they can give it.

How to Write an Effective Email Update

• Use an email distribution list so you can control who you add or remove. If they have follow-up questions or reactions, you want recipients to be inclined to reply just to you rather than reply to all. An email list provides an extra barrier to unnecessary or disruptive group-wide communication, since the replier may not know who is on the list.

• Ask people if they want to be put on the list and provide an easy option for people to unsubscribe.

• When new stakeholders start at your company, don’t forget to offer to add them, and forward helpful recent updates.

• Consider a more detailed email update for your manager and a briefer one for general distribution. Send the latter to everyone you identified in your stakeholder group.

• Save your manager some time by making it easy for them to copy and paste an exec summary from the top of your email update into their own weekly update email to forward onto their own stakeholder group.

• Don’t use the “bcc” (blind carbon copy) function. When a recipient later discovers you have also been sending to hidden recipients, the unfortunate assumption is that you have not been transparent with them.

Always start your one-on-one with “How are you?” One-on-ones are perfect for building a personal, trusting relationship.

Also, a regularly scheduled one-on-one helps you and your manager resist the temptation to send too many emails or hold meetings to resolve every single issue that arises. You only need to meet when there are urgent issues; others can wait until your next one-on-one. Often, an answer to a problem will come up in the meantime.

Occasionally, utilize your one-on-one for a career development and personal growth discussion—seek feedback and identify areas of skills development. Create and share a simple individual development plan (IDP). Review roughly once per month to understand how your manager perceives your progress—making adjustments as necessary and asking your manager for support.

An email template, IDP template, and further advice for running your one-on-ones is available online at http://www.influentialpm.com.

4. Communicate the Bottom Line Up Front—Don’t Keep Them Guessing

Whether in emails, one-on-one meetings, group discussions, or informal chats, nothing is more frustrating for a stakeholder than waiting for you to get to the point. While you ramble on, they are asking themselves questions such as the following:

• Why am I reading or listening to this? Don’t make me guess.

• What are the implications? Don’t make me worry or think for you.

• Where is this conversation going? Can you stay on point?

• What do you want from me? Action? Is this just an FYI? Am I about to be asked to make a decision?

Instead, bottom line up front: deliver the “so what?” points first, then fill in the details. Be clear about implications and any actions you want your listener to take. Not sure where to start? Imagine you’ve been asked a question about each of your priorities, decisions, or issues. Start with the conclusion first and finish your answer within 30 seconds.

In emails, start with the outcome first—so your communications stand a higher chance of being read. If you want to go into more detail, write an executive summary (you can start the summary with the acronym TL;DR which stands for “too long; didn’t read”) and include details “below the line” or add links to documentation the recipient can choose to read should they want further information.

Don’t pad bad news between good news or roll it in with small talk to soften the blow. It isn’t rude to skip the small talk if there’s something that needs immediate attention. Managers get hundreds of demands on their time each day—you stand a better chance of getting their attention if you quickly get to the point.

5. Always Provide a Recommendation and Options When Communicating a Problem

When you approach a manager with a problem, know that just passing it on to them doesn’t mean the problem has gone away. You may feel better after describing in detail your struggles, frustrations, barriers, constraints, and complaints, getting it all out of your system. You might think that you have done your bit by escalating the issue and that it is now someone else’s problem to resolve. But don’t be surprised if your manager replies, “Well, what are you going to do to solve that?”

Usually managers want you to feel confident in addressing issues without involving them every time. They may be happy to guide you, contribute to the team effort in resolving the problem, or intervene in high-impact urgent problems, but they won’t want to do all the thinking for you.

So be ready to own the problem by doing the following:

• Before escalating the issue, think about two or three possible solutions. Some might be within your power to solve; others may require your manager’s help.

• Don’t include options that are unfeasible or unpalatable, just to get your manager to support your desired solution. That is manipulation.

• In your communication, describe the problem, followed immediately by your solution options.

• Recommend your preferred solution. Let your manager either agree with you or suggest an alternative approach.

6. Be a Low-Maintenance Employee—You’ll Earn Trust and Become Part of the Inner Circle

You have probably heard the saying “the squeaky wheel gets the oil.” While that might be true for some, it isn’t a particularly attractive trait in a product manager. Accept the challenges that come with your role. New business priorities, changes in direction, conflicting needs, resource constraints, unexpected disruptions, aggressive deadlines, and conflicts with other departments are all to be expected. How you handle them is what matters.

Come with Recommendations

With hundreds of people reporting to him and constant requests from the president and other executives of the company, demands on this Fortune 500 COO were intense. He was trying to make an engineering organization work more effectively, while managing a tight budget and addressing slower-than-expected customer growth.

I was called to a meeting with the COO by one of his peers—a general manager for a business unit. The agenda wasn’t clear, but I soon learned that the general manager was pushing the COO to make decisions on several of our product priorities. He was unprepared for the meeting and didn’t have any suggested solutions or recommendations for all the problems he wanted the COO to fix. I could sense the COO getting frustrated and alarmed—here he was being pressured to make critical decisions without having either the time or data to process them.

I turned to the general manager and suggested, “How about we take this discussion offline, you and I, and then come back to the COO with a recommendation? We’ll try to come up with something we think we can all support.”

The relief in the COO’s face was apparent. I had just lifted a load from his shoulders. He readily agreed to a follow-up meeting once we were ready with our recommendations. A few days later, he came by to thank me for being prepared to step in. I told him it was nothing and joked that “one of my jobs is to try to make us all more successful—that way I can be successful too.”

Years later, when he moved to a different company, that same manager reached out to recruit me for his team.

Managers have only so much time to make their teams productive. While they may have more sway in an organization, they, too, are often highly constrained. They certainly don’t want to spend much of their time on a single employee. You don’t want a reputation for being difficult to work with when something doesn’t go your way. Instead, you want your manager to see you as their go-to person, especially when it comes to addressing complex issues or changes.

As a rule, then, build the following practices and attitudes into your work life:

• Be judicious as to what issues you escalate—Try to be self-sufficient but communicative. Escalate only what truly needs their attention (even if it means a little more pain for you).

• Monitor your emotional response—Be wary of complaining (about your workload, about other team members, etc.) or getting emotional with your manager. Save such expressions for times (hopefully infrequent) when you have a serious issue and need to jolt your manager into action.

• Focus on making the company and your manager as successful as possible—Understand your manager’s goals and support them. Your efforts will be all the more appreciated.

• Develop empathy for the rest of the organization—Understand how each team does its job, along with its needs and challenges. By doing so, you’ll be more likely to assume good intent and appreciate where others are coming from when conflict arises.

• Accept what you cannot change—Understand, for reasons that may not be entirely clear to you, that your manager may occasionally overrule you or task you with an essential (but less fun) initiative.

As a low-maintenance employee, you often become a trusted insider, sending your manager the message that they can delegate tough jobs to you, value your involvement in key meetings, and think of you as someone who will get the job done with a minimum of fuss.

Product Governance

You might already benefit from a regularly designated check-in with senior decision-makers that allows you to communicate and receive guidance on overall product priorities and progress. However, if not, perhaps you are experiencing misunderstandings or having trouble gaining agreement on your product priorities or desired outcomes. There may be a lack of clarity in regard to roles and responsibilities, or resourcing may be misaligned with delivery expectations. Maybe you lack sufficient input on business objectives to inform your decision-making. At a regular meeting—say monthly—your key stakeholders can collectively review, discuss, and align behind your recommended product direction.

If you don’t currently have such a forum and feel one might be helpful, suggest it to a senior product leader as a means to improve collaboration and visibility. You need to be empowered and confident that you are focused on delivering what the organization believes to be the highest-value initiatives. For the most efficient use of your time, you and other product managers can team up to run a single session.

The benefits of such regular check-ins include the following:

• An opportunity for stakeholders to influence and align—Product managers present roadmaps and recommendations, gather input on decisions, and identify tradeoffs between competing objectives. Stakeholders voice concerns and ideas and provide perspectives. Importantly, other stakeholders hear them and join the debate. It helps to have opposing views surface at the same time to accelerate alignment. You can identify hidden issues and flag these for later follow-up, to get resolution.

• A review of the allocation of resources—It’s common to have more priorities than can be adequately resourced. And what can get done with the available resources within the time available is often overestimated. A product forum provides an opportunity for a reality check, reviewing how resources are deployed and what reasonably can (and cannot) be worked on. It can help inform which priorities should progress in the near future and which should not. To ensure they set realistic expectations, make sure that your product forum participants discuss both roadmaps and resource allocation together (not separately).

• Goals, commitments, and risks—A forum provides a stage for product managers to remind the organization of why specific initiatives are being worked on and to ensure business goals haven’t shifted in the meantime. Project KPIs are shared, so stakeholders understand what success looks like. (Don’t just recite a laundry list of initiatives; emphasize the business reasons behind them.) Risks and mitigation plans can be agreed upon. If for any reason, a commitment looks to be in jeopardy, the product manager can request help, whether to remove obstacles or enlist assistance from other teams.

• A green light—A product forum can serve as a place in which to review substantive (potentially high-investment, high-risk, or both) ideas and initiatives. You can discuss their business benefits and formally approve their implementation. Alternatively, if a project looks less promising than initially hoped, the forum is a place for product managers to recommend whether to halt it.

Guard against the tendency of the product forum to become primarily a place for tactical discussion, which is ineffective and disempowering. Product forums must be kept high-level. Product managers must take care to make sure they do not become occasions for simply providing status updates, gathering requirements, or enabling stakeholder to constantly overrule or second-guess the product manager’s decisions. If you observe any of the following issues, you may be slipping into dangerous territory:

• Someone other than a senior product leader runs the meeting. A product forum is meant to be a place for the product team to lead the discussion and build confidence.

• Individual or team performance, date slippage, or delivery pace is a regular topic of conversation. This can lead to finger-pointing between the product team and engineering.

• Past decisions are consistently revisited. Pet ideas resurface again and again for re-evaluation.

• Meetings include detailed feature reviews or demos. There’s discussion about scope, design, or functionality instead of goals, metrics, and roadmaps.

• Project timelines are presented and specific delivery dates mandated.

• Product managers abdicate their responsibility to make prioritization decisions and leave such decisions to the forum instead. While they should welcome the opportunity a product forum provides for everyone’s point of view to be heard, product managers should own a clear data-driven case for what initiatives matter most.

Designed well, a product forum can serve to align stakeholders behind product roadmaps, keeping everyone focused on the business priorities that matter. Product managers should take input from forum meetings but remain responsible for deciding product priorities (and accountable for those decisions).