Making Use of Lessons Learned

Learning is important for its own sake, but lessons reveal their real power when they are put to use. First, the lessons learned from the conduct of a project can be disseminated to practitioners, academics, and policymakers, and can also be used to expand the project into a program with multiple locations—perhaps even to bring the program to a national scale. In the longer run, these lessons can inform and improve the way grantmaking is done at the foundation.

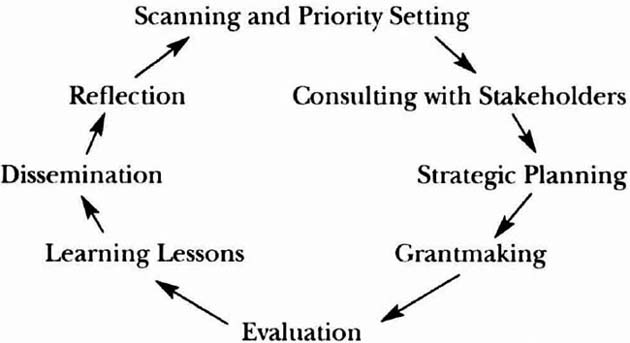

Harvesting the lessons learned closes the loop on program work. Grantmaking begins with scanning and priority setting, continues with strategic planning, goes through the phases of funding and evaluating projects, and after the lessons are learned and tested by dissemination, their full meaning is reflected on. Finally, the lessons learned are fed back into a new round of scanning and priority setting. Indeed, the entire cycle can be depicted as a circle, or wheel, as shown in Figure 11.1.

Although many metaphors could be applied to describe this wheel, perhaps the best one is agricultural. Starting with scanning and priority setting, and moving clockwise, the first four activities represent a sowing of ideas and dollars. The last four represent a reaping of lessons and outcomes. Because the process is circular rather than linear, there is no single starting point, but for purposes of description, we'll begin at the top.

Figure 11.1. The Grantmaking Cycle.

1. Scanning and priority setting. Activities under this rubric include the first three found under the heading “The Five Steps in Setting Priorities” in Chapter One: niche identification, literature reviews, and scans of other foundations' programming. These steps establish the intellectual underpinnings of any grants program.

2. Consulting with stakeholders. This heading contains the two remaining priority-setting approaches discussed in Chapter One: consulting with those who will be affected by grantmaking in a particular area, including the disenfranchised, and possibly making a few small experimental grants (sometimes referred to as program testing). These efforts guarantee that the program will be designed to meet the needs and desires of the people it is intended to help.

3. Strategic planning. Armed with data, responses from stakeholders, and lessons from the learning grants, the foundation enters a formal process of structuring the grantmaking program, including setting goals, establishing timelines, and allocating resources.

4. Grantmaking. Once the strategic plan is in place, the program of grant investment can proceed in earnest. Although the initial direction of the grants will be determined by the three previous steps, midcourse corrections will be made as lessons are learned from the projects. Included here as well are such activities as formative evaluation and networking of grantees.

5. Evaluation. Midcourse and closing lessons are provided by the summative evaluation of funded projects, by evaluations of clusters of projects, and sometimes even by meta-evaluations that assess the full range of the foundation's programmatic activities. It should be noted, however, that evaluation is best understood as a process for gathering data and recommending action. Final responsibility for making action decisions rests with the program staff.

6. Learning lessons. The data and recommendations provided by evaluators must be read, discussed, and then translated into decisions. This act of synthesis and leadership does not occur spontaneously; time must be set aside for it, and the foundation must budget resources to ensure that it happens.

7. Dissemination. Once the lessons have been digested, they can be further refined by sharing this valuable information with practitioners, academics, or policymakers. This information is often used to support an expansion of the project to other sites, but preliminary lessons should be shared widely with all who can use them. Taking a proprietary attitude toward lessons learned is not only fundamentally selfish but actually counterproductive, for a foundation's impact is greatly limited if the lessons it has learned remain unknown.

8. Reflection. Once disseminated, the lessons will be commented on, criticized, refuted, validated, or amplified by outsiders. For the foundation, this process will provide new lessons to be learned, as some of the old lessons will be disproved, many more will be validated, and most will be modified in some fashion. It is important for you to consider the meanings of these lessons and their implications for how you do your job. Again, opportunities for reflection do not occur spontaneously. Time and resources must be specifically budgeted so that foundation staff can consider what has been learned from past programming and apply these lessons to future activities. It is especially important to conduct deliberate and systematic reflection, for the highly tested and refined lessons learned during this eighth stage on the wheel will be invaluable in informing the next round of priority setting and scanning.

And so it is that information, data, and lessons flow around the wheel, with experience informing new ventures, and new knowledge improving on old practice. Unfortunately, some foundations do not fully maximize the power of the wheel. Too few take the time to systematically harvest their lessons, fully reflect on the meaning of those lessons, and energetically share them with the outside world. These are all opportunities lost, for it is good professional practice to become very intentional in maximizing the foundation's ability to capture, assimilate, and broker information.