Chapter 6

Welcome to the Wild, Wonderful, Wacky Web

In This Chapter

![]() Understanding web pages and URLs

Understanding web pages and URLs

![]() Pointing, clicking, browsing, and other basic skills

Pointing, clicking, browsing, and other basic skills

![]() Opening lots of web pages at the same time

Opening lots of web pages at the same time

![]() Discovering the web from your phone

Discovering the web from your phone

![]() Discovering Internet Explorer and Firefox

Discovering Internet Explorer and Firefox

![]() Installing a browser other than Internet Explorer

Installing a browser other than Internet Explorer

People now talk about the web more than they talk about the Internet. The World Wide Web and the Internet aren’t the same thing — the World Wide Web (which we call the web because we’re lazy typists) lives “on top of” the Internet. The Internet’s network is at the core of the web, and the web is an attractive parasite that requires the Net for survival. However, so much of what happens online is on the web that you aren’t really online until you know how to browse the web.

This chapter explains what the web is and where it came from. Then it describes how to install and use some popular web browsers and how to use web browsers to display web pages. If you’re already comfortable using the web, skip to Chapter 7.

What Is the World Wide Web?

So what is the web, already? The World Wide Web is a bunch of “pages” of information connected to each other around the globe via the Internet. Each page can be a combination of text, pictures, audio clips, video clips, animations, fill-in-the-blank forms, and other stuff. (People add new types of other stuff every day.)

Linking web pages

What makes web pages interesting (aside from the fact that there seems to be a web page about every topic you can possibly think of) is that they contain links that point to other web pages. When you click a link, your browser fetches the page the link connects to. (Your browser is the program that shows you the web — read more about it in a couple of pages.) Links make connections that let you go directly to related information. These invisible connections between pages resemble the threads of a spider web — as you click from web page to web page, you can envision the “web” created by the links.

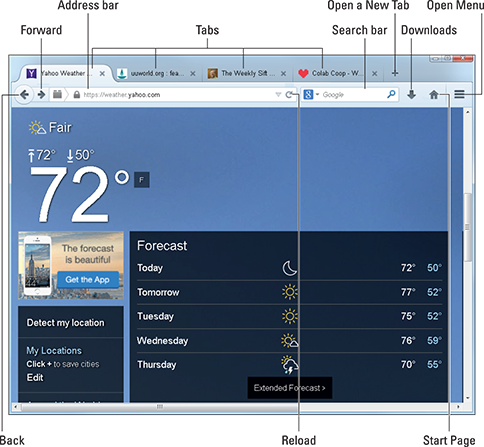

Figure 6-1 shows a web page. Underlined phrases are links to other web pages, but a lot of non-underlined text is, too — move the mouse pointer around a page and see wherever it turns into a little hand. Anywhere a hand appears is a link, even if it isn’t underlined. Pictures can be links, too.

Figure 6-1: This web page is displayed in the Firefox browser.

What’s remarkable about the web is that it connects pieces of information from all around the planet, on different computers and in different databases (a feat you would be hard pressed to match with a card catalog in a brick-and-mortar library). Pages can be linked to other pages anywhere in the world so that when you’re on the web, you can end up looking at pages from Singapore to Calgary, or from Sydney to Buenos Aires, all faster than you can say “Bob’s your uncle,” usually. You’re only seconds away from almost any site, anywhere in the world.

Finding the page you want

An important characteristic of the web is that you can search it — over a trillion pages. For example, in fewer than ten seconds, you can find a list of web pages that contain the phrase domestic poultry or your own name or the name of a book you want to find out about. You can follow links to see each page on the list to find the information you want. See Chapter 13 to see how to use a search engine to search the web.

Where’s that page?

Before you jump onto the web (boing-g-g — that metaphor needs work), you need to know one more basic concept: Every web page has a web address so that browsers, and you, can find it. Great figures in the world of software engineering (one guy, actually, named Sir Tim Berners-Lee) named this address the Uniform Resource Locator, or URL. Every web page has a URL, a series of characters that begins with http://. (How do you say URL? Everyone we know pronounces each letter, “U-R-L” — no one says “earl.”) Many URLs include the letters www, but not all do. Now you know enough to go browsing. For more entirely optional details about URLs, see the later sidebar “Duke of URL.”

Browsing to Points Unknown

It’s time to check out the web for yourself, using a browser, the program that finds web pages and displays them on your screen. Fortunately, if you have any recent version of Windows, any recent Mac, any netbook, almost any other computer with Internet access, or a smartphone or tablet, you probably already have a browser.

Here are the most popular browsers:

- Firefox (shown in Figure 6-1) is the browser from the open source Mozilla project at www.mozilla.org. You can download Firefox for free for Windows, Macs, and Linux computers. Firefox is used by about 24 percent of web users.

- Chrome, shown in Figure 6-2, is from Google, the company responsible for the www.google.com search site and lots and lots of free, web-based services. About 60 percent of people use Chrome, which you can download for free for Windows, Macs, and Linux at www.google.com/chrome. It also comes on every Android phone and tablet. Google has a plan for Chrome to become its own operating system, competing with Windows, currently available on laptop computers called Chromebooks.

- Internet Explorer (IE), shown in Figure 6-3, is the browser that Microsoft has built into every recent version of Windows. Fewer than 10 percent of people (and dropping) still use IE. It is available as a free download for many earlier versions of Windows (at www.microsoft.com/ie) but not for the Mac. IE also runs on Windows Mobile phones and tablets. See the nearby sidebar “Our advice: Switch from Internet Explorer to Firefox, Safari, or Chrome.”

- Safari, shown in Figure 6-4, is the Apple browser for the Mac, iPad, iPhone, and iPod touch. Windows has a version, too, although we’ve never heard of anyone other than us using it. You can download the latest versions from www.apple.com/safari.

Figure 6-2: The Google Chrome browser displays another web page.

We describe Chrome and Firefox in detail in this book, and we mention Internet Explorer and Safari here and there. All browsers are similar, enabling you to view web pages, print them, and save the addresses of your favorite pages so that you can return to them later. If you want to try a different browser, see the section “Getting and Installing a Browser,” later in this chapter.

Figure 6-3: Your typical web page, viewed in Internet Explorer 11.

Figure 6-4: Safari is Apple’s web browser.

Web Surfing with Your Browser

When you start your web browser — Firefox, Chrome, Internet Explorer, Safari, or whatever — you see a window that displays one web page, with menus and icons along the top. Figure 6-1 (shown earlier in this chapter) illustrates Firefox, Figure 6-2 shows Google Chrome, Figure 6-3 shows Internet Explorer, and Figure 6-4 shows Apple’s Safari. Other browsers look similar, but with different menus and icons along the top.

The main section of the browser window is taken up by the web page you’re looking at. After all, that’s what the browser is for — displaying a web page. Which page your browser displays at startup — your start page — depends on how it’s set up. Many ISPs arrange for your browser to display their home pages; otherwise, until you choose a home page of your own, IE tends to display a Microsoft page, Firefox and Chrome usually show a Google search page, and Safari shows a page from the Apple website. Chapter 7 explains how to set the start page to a web page you want to see.

The buttons, bars, and menus around the edge help you find your way around the web and do things such as print and save pages. Here are some of the most important buttons and menus at the top of your browser window:

- Back button: Click to display the last page you looked at, as described in the later section “Backward, ho!”After you click Back, you can click Forward to return to the page you were looking at.

- Reload button: Click to reload the page you’re looking at now from the web. Maybe something changed since you loaded it, or maybe it didn’t load correctly the first time. F5 is a keyboard shortcut.

- Home button: Click to display your start page (or home page), as described in Chapter 7.

- Address bar: Displays the web address (URL) of the current page. You can enter the URL of a page to display, as described in the later section “Going places.”

- Search bar: Firefox has a separate Search bar, to the right of the Address bar, where you can type search terms. Other browsers combine the Address and Search bars. See Chapter 13 for details.

The rest of this chapter explains how to use these and other features of your browser.

Getting around

You need two simple skills (if we can describe something as basic as making a single mouse click as a skill) to get going on the web. One is to move from page to page on the web, and the other is to jump directly to a page when you know its URL (web address). Okay, we know that you aren’t actually moving — your web browser displays one page after another — but browsing feels as though you’re cruising (or surfing, depending on which metaphor you prefer) around the web.

Moving from page to page is easy: Click any link that looks interesting. That’s it. Underlined blue text and blue-bordered pictures are links, and sometimes other things are, too. Anything that looks like a button is probably a link. You can tell when you’re pointing to a link because the mouse pointer changes to a little hand. Clicking outside a link selects the text you click, as in most other programs. Sometimes, clicking a link moves you to a different place on the same page rather than to a new page.

Backward, ho!

Sometimes, clicking a link opens the new page in a new browser window or tab — your browser can display more than one web page at the same time, each in its own window or in tabs in one window. If a link opens a new window or tab, the Back button does nothing in that window, but you can still switch back to the old window by clicking it.

Going places

Someone tells you about a cool website and you want to take a look. Here’s what you do:

- Click in the Address bar, near the top of the browser window.

Figures 6-1, 6-2, 6-3, and 6-4 show where the Address bar is.

- Type the URL in the box.

The URL is similar to http://net.gurus.org — you can just type net.gurus.org and your browser supplies the http:// part. Be sure to delete the URL that appeared before you started typing.

- Press Enter.

- If the entire address in the Address bar is highlighted, when you type, the new URL replaces what was there before. If not, click in the Address bar until the entire old address is highlighted.

- You can leave the http:// off URLs when you type them in the Address bar. Your browser can guess that part! Many web addresses include a name that ends with .com, but not all do. See the later sidebar “Why .com?” for more information.

- When you start typing a URL, your browser helpfully starts guessing the address you might be typing, suggesting addresses you’ve already typed that start with the same characters. The browser displays its suggestions in a list just below the Address bar. If you see the address you want on the list, click it — there’s no point in typing the rest of the URL if you don’t have to!

If you receive URLs in email, instant messages, or documents, you can usually click on them — many programs pass along the address to your browser. Or, use the standard cut-and-paste techniques and avoid retyping:

- Highlight the URL in whichever program it appears.

That is, use your mouse to select the URL so that the whole URL is highlighted.

- Press Ctrl+C (Command+C on the Mac) to copy the info to the Clipboard.

- Click in the Address bar to highlight whatever is in it. (Click again until the entire URL is selected, so the whole thing gets replaced.)

- Press Ctrl+V (Command+V on the Mac) to paste the URL into the box, and then press Enter.

A good place to start browsing

You find out more about how to find things on the web in Chapter 13, but for now, here’s a good way to get started: Go to the Yahoo! News page. To get to Yahoo! News, type this URL in your browser’s Address bar and then press Enter:

news.yahoo.com

The Yahoo! website includes lots of different features, but its news site should look familiar — it’s similar to a newspaper on steroids. Just nose around, clicking links that look interesting and clicking the Back button on the toolbar when you make a wrong turn. We guarantee that you’ll find something interesting.

What not to click

Here are some links not to click:

- Don’t click ads claiming that you just won the lottery or a free laptop or anything else too good to be true.

- Don’t click messages on web pages claiming that your computer is at risk of dire consequence if you don’t click there. Yeah, right.

- Don’t click OK in a dialog box that asks about downloading or installing a program, unless you’re deliberately downloading and installing a program. (See Chapter 7.)

- Don’t click any link that makes you suspicious. Your instincts are probably correct!

If one of these messages appears in a browser window, the safest thing to do is to close the window by clicking the X box in the upper-right corner (or on a Mac, the red Close button in the upper-left corner).

This page looks funny or out of date

Sometimes, a web page becomes garbled on the way in or you interrupt it (by clicking the Stop button on the toolbar or by pressing the Esc key). You can tell your browser to retrieve the information on the page again. Click the Reload button (shown in Figures 6-1, 6-2, 6-3, and 6-4) or press Ctrl+R (Windows) or Command+R (Mac).

Get me outta here

Sooner or later, even the most dedicated web surfer has to stop to eat or attend to other personal needs. You leave your browser in the same way you leave any other program: Click the Close (X) button in the upper-right corner of the window (or on a Mac, the red Close button in the upper-left corner) or press Alt+F4 (Windows) or Command+W (Mac). Or, just leave the program running and walk away from your computer. If you have multiple tabs open (described in “Tab dancing,” later in this chapter), the program asks whether you want to close them all.

Viewing Lots of Web Pages at the Same Time

When we’re pointing and clicking from one place to another, we like to open a bunch of browser windows so that we can see where we’ve been and go back to a previous page by just switching to another window. You can also arrange windows side by side, which is a good way to, say, compare prices for The Internet For Dummies at various online bookstores. (The difference may be small, but when you’re buying 100 copies for everyone on your Christmas list, those pennies can add up. Oh, you weren’t planning to do that? Drat.) Your browser can also display lots of web pages in one window, by using tabs (as explained in the section “Tab dancing,” a little later in this chapter).

Wild window mania

To display a page in a new browser window, click a link with the right mouse button and choose Open in New Window (or Open Link in New Window) from the menu that pops up. To close a window, click the Close (X) button in the upper-right corner of the window frame or press Alt+F4, the standard close-window shortcut. (On a Mac, click the red button in the upper-left corner of the window or press Command+W.)

You can also create a new window without following a link: Press Ctrl+N. (Mac users, press Command+N.)

Tab dancing

We’ve all heard about how multitasking is a bad idea, but sometimes it’s very useful to have several web pages open at the same time. Web browsers have tabs, which are multiple pages you can switch among in a window. Figures 6-1, 6-2, 6-3, and 6-4 show browsers with several tabs across the top. The name of the tab is shown on each tab, like old-fashioned manila folder tabs. One tab corresponds to the page you see; that tab is a brighter color.

Just click a tab to show the page. To make a new, empty tab, click the New Tab (the tiny, blank tab to the right of the other tabs), press Ctrl+T (Windows) or Command+T (Mac), or right-click an existing tab and choose New Tab from the menu that appears. You can also open a new tab by right-clicking a link and choosing Open in New Tab (or Open Link in New Tab) from the menu that pops up. Click the X on the tab to get rid of it, or right-click the tab and choose Close Tab. (You may have to hover the mouse on the tab to see its X.)

For most purposes, we find tabs more convenient than windows, but multiple windows are useful if you want to compare two web pages side by side. You can use both tabs and windows; each window can have multiple tabs. In most browsers, you can drag a tab from one browser window to another, or drag a tab out to the desktop to make a new window. And like all windows, you can drag their edges to move or resize them.

Browsing from Your Smartphone or Tablet

Internet-connected phones and tablets — such as the iPhone and iPad and Android and Windows Mobile phones and tablets — can browse the web, too. Some use your cell connection to load pages and others use Wi-Fi. Of course, on a phone you can see only teeny, tiny web pages on their teeny, tiny screens, but phone-based browsing can still be incredibly useful, especially when you’re looking for a good restaurant recommendation. The iPad and other Wi-Fi-connected tablets have browsers, too, and their screens are large enough for a tolerable browsing experience.

The iPhone and iPad come with Safari, Android phones come with Google Chrome, and Windows Mobile phones come with IE. All these pint-size browsers have Back buttons and Address bars and most of the same basic features as their larger siblings.

Getting and Installing a Browser

Chances are, a browser is already installed on your computer. If you use Internet Explorer, we think you’re better off installing either Firefox or Chrome, for speed and safety reasons. Fortunately, browser programs aren’t difficult to find and install, and Firefox, Chrome, and Safari are all free.

Getting the program

To get Firefox (for Windows or Mac or any of the other dozen computers it runs on), visit www.mozilla.com. For Chrome, go to www.google.com/chrome. To get or upgrade Internet Explorer, go to www.microsoft.com/ie. Safari is available at www.apple.com/safari. Use your current browser to go to the page and then follow the instructions for finding and downloading the program. (Take a look at Chapter 7 for advice about downloading files.) If you are using a smartphone or tablet, go to your app store (the App Store on Apple devices and the Play Store on Androids).

Running a new browser for the first time

To run your new browser, click the browser’s attractive new icon. If you use Windows, the default browser also appears at the top of the left column of the Start menu, too.

Your new browser will probably ask whether you want to import your settings — including your bookmarks and favorites — from the browser program you’ve been using. If you’ve already been using the web for a while and have built up a list of your favorite websites (as described in Chapter 7), take advantage of this opportunity to copy your list into the new browser so that you don’t have to search for your favorite sites all over again.

It will also ask whether to make it the “default” browser, that is, the one used when another program opens a web page. Browsers are very jealous, so if you don’t say yes, it’ll keep asking you each time you run it. Or if you do say yes, the next time you run any other browser, that browser, feeling jilted, will offer to make itself your default. Our advice is that once you find a browser you like, make it your default and stick with it.

Apple’s iOS devices don’t let you change the default browser from Safari. If you use an Android device, you can change the default; open Settings, choose More, choose Application Manager, and scroll right to choose All. Then choose the current default browser and choose Clear Defaults. The next time you click a link in an email or other message, Android will ask what program to use; choose your favorite browser.

Web browsers remember the last few hundred pages you visited, so if you click a link and decide that you’re not so crazy about the new page, you can easily go back to the preceding one. To go back, click the Back button on the toolbar. Its icon is an arrow or triangle pointing to the left, and it’s the leftmost button on the toolbar, as shown in Figures

Web browsers remember the last few hundred pages you visited, so if you click a link and decide that you’re not so crazy about the new page, you can easily go back to the preceding one. To go back, click the Back button on the toolbar. Its icon is an arrow or triangle pointing to the left, and it’s the leftmost button on the toolbar, as shown in Figures  Bad guys can easily create email messages where the URL you see in the text of a message isn’t the URL you visit; the bad guys can hide the actual URL. Keep this warning in mind if you receive mail that purports to be from your bank — if you click the link and enter your account number and password in the web page that appears, you may be typing it into a website run by crooks rather than by your bank. See Chapter

Bad guys can easily create email messages where the URL you see in the text of a message isn’t the URL you visit; the bad guys can hide the actual URL. Keep this warning in mind if you receive mail that purports to be from your bank — if you click the link and enter your account number and password in the web page that appears, you may be typing it into a website run by crooks rather than by your bank. See Chapter  For information related to the very book you’re holding, go to

For information related to the very book you’re holding, go to