Chapter 4

Leading People and Projects

Rumors of strategic changes that would affect shift work and overtime had people at the auto parts plant on edge. The mood in the break room was tense as Peter, an introverted vice president of manufacturing, walked in and approached the employees gathered there. “How’s your mama?” he earnestly asked one young worker. Peter’s body language was attentive as he listened to the employee describe the progress his mother had made since her illness the previous year. These kinds of conversations continued with others as Peter made his way around the room.

Later that day, Peter gave a more formal update on the state of the company, then invited questions. As he answered, he neither talked down to those assembled nor glossed over the uncertain times ahead. He listened to concerns and directly addressed overtime issues. And he committed to keeping people in the company informed. When he walked back to his waiting car, I took the opportunity to ask several of the workers about their impressions of Peter. The consensus was “He’s cool.”

Peter had quiet presence. He had learned an important lesson about getting work done. People want to be treated as more than cogs in a machine. They want to matter. By being genuine and showing a sincere interest in their top-of-mind issues (both personal and work related), Peter’s honest communication built trust and connection.

Can Introverts Really Be Leaders?

How do introverted leaders do it? This chapter is about being a successful leader in an organization. Let’s start with an elephant-in-the-room question asked by extroverts and introverts alike: can introverts really be leaders?

The answer? Yes, of course. Hell, yes!

Recent surveys of people in top corporate leadership show that engineering, finance, and operations are the most common pathways to the top, including CEO positions. Plenty of data exists that these professional roles are staffed by high numbers of analytical, introverted people.

Many of the leaders who have presided over astonishing gains in the performance of their companies would hardly be described as “extroverts.” Such leaders mostly combine the introvert’s tenacity and focus on the business with humility and a willingness to share leadership.

Researchers Adam Grant, Francisco Gino, and David A. Hofmann found that “extroverted leaders can actually be a liability for a company’s performance, especially if the followers are extroverts, too.” In short, new projects can’t blossom into profitability if the leader is too busy being outgoing to listen to or act upon everyone’s ideas. An introverted leader, the researchers say, is more likely to listen to and process the ideas of an eager team.

However, if an introvert is leading mostly passive followers, it “may start to resemble a Quaker meeting, lots of contemplation but hardly any talk,” Grant, Gino, and Hofmann wrote. To that end, a team of passive followers might benefit from an extroverted leader.9

Grant, a professor at University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School, says introverts “tend to be less threatened by others’ ideas. And they’ll collect a lot of them before determining a vision.” He also said, “Introverted leaders . . . are more likely to listen carefully to suggestions and support employees’ efforts to be proactive.”10

I have found this in my own work with introverted leaders. Their patience, calm demeanor, and thoughtful presence create an open, inviting space for the talkers in the crowd to explore their ideas out loud.

Introverts also might last longer in their jobs, according to a study that focused on city managers.11 The researchers determined that introverted city managers are inwardly oriented and reflective, that they consider ideas deeply before acting—and they tend to have longer tenures.

Another study found introverts’ contributions are more appreciated because they exceed the low expectations of people who believe introverts are withdrawn and may be too anxious to live up to their potential. Some have the misconception that they contribute little and drag down colleagues’ morale. Researchers found, in fact, it was not the case that introverts “contribute less than team members expect and the contributions they do make are not valued highly over time.”12

Reframing the Traits of Strong Leaders

The traits of successful leaders get a lot of attention. Daniel Goleman, author of the best seller Emotional Intelligence, defines good bosses as “great listeners, encouragers, communicators, and courageous. They have a sense of humor, show empathy, are decisive, take responsibility, are humble, and share authority.”13

Bad bosses, he says, on the other hand, are blank walls. They’re doubters, secretive, and intimidating. They allow themselves to be ruled by their tempers and tend to be self-centered, indecisive, and arrogant. In addition, they blame others and show mistrust. Some characteristics may be more common in introverts than extroverts (and vice versa). For example, introverts might be more likely to exhibit traits such as listening, while a trait like friendliness might be more overt in extroverts. But all traits are typically mixed and matched, and introverts are no more likely to be good or bad bosses than extroverts. Humor, for example, can be just as much a part of the introvert’s repertoire as extroverts. Introvert Warren Buffet was asked what he wanted written on his tombstone. With the hint of a smile, he didn’t skip a beat: “God, he was old!”14

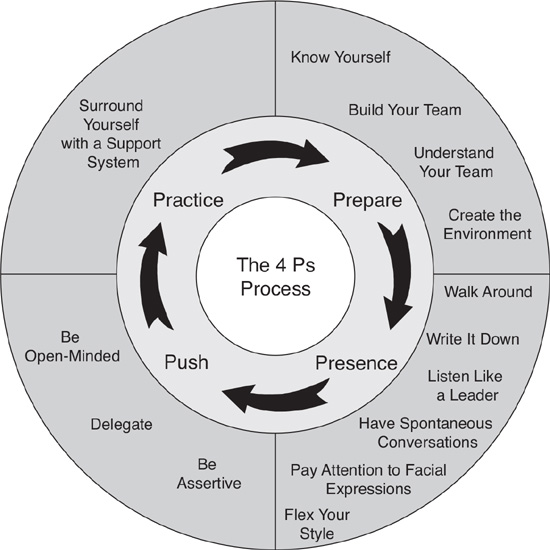

Let’s look at how introverts can build on their leadership strengths by using the 4 Ps. Figure 2 (see page 57) is a summary of the steps you can take to practice strengthening your leadership muscle. Refer to it often.

Prepare

Stepping into a management role can be exciting but also a bit scary. While it’s great to be recognized for your accomplishments, you’re giving up what you do well to venture into a land of ambiguity. You might wonder if you’re up to the task.

Stewart Stokes puts it well:

Managing this “toughest transition” means, first, giving up some of what you know, like to do, and that provides you with a great deal of job satisfaction and self-esteem. Second, it means taking on some of what you do not know, are not sure you will like, and that may not (at least initially) do much for your job satisfaction and self-esteem. Third, it means moving from working on tasks where there is some certainty, specificity, and even some “answers.”15

Training, coaching, and mentoring will increase your chances of leading and managing others successfully. Several steps can help prepare you for leadership responsibilities as they morph and change. And because we never stop growing, these steps are valid throughout the many phases of a leadership journey.

Consider these suggestions as you prepare for your leadership role:

• Know yourself.

• Build your team.

• Understand your team.

• Create the environment.

Know Yourself

The Benefits of Introspection

To manage others, it’s important to first manage yourself. Knowing yourself means understanding what assets and liabilities you bring to the table. With self-awareness, you can learn to channel your strengths as a leader and compensate for weaknesses. Research with more than 60 senior HR professionals found that the advantages of self-awareness are far reaching.16 Being self-aware allows you to be more objective, to detach when necessary, and show appropriate concern for others. Knowing your limitations also allows you to ask for help. Self-awareness helps you realize the value you bring to an organization and gives you the confidence to ask for challenging assignments and other opportunities you desire. As an introvert, you can use your preference for quiet time to better understand your palette of strengths and weaknesses.

Tony Hsieh, CEO of Zappos and an introverted leader, says self-awareness contributes to his continued personal growth. Discussing his associates, he said, “Without that awareness, it’s harder for them to evolve or adapt beyond who they already are.”17

Introverted leaders who are self-aware and who self-disclose can better connect with their employees. Doug Conant, former Campbell Soup CEO, who wrote the foreword to this book, said, “One of the best ways I’ve found to help people overcome their discomfort around my behavior is to simply declare myself. I tell them, ‘If you see me looking aloof, please understand that I’m shy, and I need you to call me out.’ By declaring myself in this way, I’ve found other people quickly, and compassionately, adapt to my style.”

He continued:

I’ve also found that doing this helps people become much more comfortable about declaring themselves to me. When you establish a personal connection, great things can happen. After I declared myself to one new hire, he confided to me that he was a recently divorced father with two boys, and that he needed to have extra flexibility at work. I completely understood, and I told him to make whatever arrangements he needed to meet the demands of his job and his family. Over the ensuing years, he went the extra mile for our company because we had declared ourselves to each other early on.18

Blind Spots

Self-awareness can also help point out your blind spots. Take Rachel, a senior finance director who raised her hand at the end of a leadership seminar and said, “I am an introvert and try to avoid meetings. Now that I am running a department of mostly introverts, I find everyone is perfectly fine with not meeting and conducting business via email. I am concerned this might become a problem: never meeting to discuss issues!”

The rest of the group of introverted leaders smiled in recognition. They advised Rachel to schedule face-to-face time with her team so they could all build relationships that would help them better accomplish their tasks. By meeting and clarifying their respective roles and work challenges, they will achieve better results, her introverted peers advised her. Though she dislikes meetings, Rachel realized that this was a potential blind spot and was willing to change for the good of her team.

My friend, the late C. J. Dorgeloh, was an experienced project manager. As an introvert, she had to push herself to bring leadership presence to public and group situations.

I am much more comfortable behind the scenes. As a project leader, there are times when I can be very quiet, taking it all in. This can hamper my effectiveness as a leader if I’m not aware of addressing it. The group may view this as confusion or lack of direction so I need to consciously verbalize more often than I would naturally to keep them in the loop and things moving. (Interview with author)

C. J. stayed on top of her blind spot by getting in the shoes of her team, and as a result, she flexed her style when necessary. She was taking the perception gap into consideration by doing what she could to manage perceptions while still staying true to herself.

Build Your Team

Selecting the right team is a key variable in your success as a leader. Let’s look at two key questions:

1. Are you choosing the right people by avoiding recruiting bias?

2. How can you prepare for interviews so you get the best people for the job?

Avoid Recruiting Bias

In the recruiting stage, make sure you are not overlooking introverts. In internal hiring, that can happen because introverts have not been out there selling themselves. Sallie, an introverted recruiting manager who participates in promotion and hiring, is aware of the bias that often exists when less visible and vocal candidates are discussed. She makes a point of researching potential team members who are qualified but have not been especially vocal. “Being an introvert myself, I am especially sensitive to this situation. I see my role as an introvert advocate in hiring discussions.”

Ideas for Hiring Managers

Introverted interviewers can also use their skill at preparation to ensure that interviews accomplish the goal of getting the best person for the job. This entails going “beyond the polished resumes, pre-screened references and scripted answers to hire more creative and effective members for your team.”19

These five hiring tips can help you prepare for interviews and ensure that you are setting the stage for introverted candidates to show you who they really are:

1. Prep the room Avoid blazing lights and noisy areas. Putting a desk between you and the candidate interferes with rapport, but sitting too close can be off-putting for introverts, who value personal space. Try sitting kitty- corner—it creates the right amount of intimacy. If it’s a group interview, seat the candidate at the middle of the table rather than at its head so they feel less scrutinized and can make eye contact with everyone.

2. Check your bias If you’re an introvert, you most likely will be comfortable with a slower pace, pauses, and the possible self-effacing stance of an introverted interviewee. But check yourself for confirmation bias—seeking answers that support your case and minimizing other important responses. Be clear about the skills and traits you need for the position. Consider how comfortable you feel with a person who mirrors your style, and try to diversify your pool of candidates by being open to everyone.

3. Schedule adequate time If you schedule yourself too tightly between interviews, you’ll likely feel pressured and impatient if the person doesn’t talk quickly enough. Introverted candidates are likely to pause before answering questions, and they may not fight for conversational space. Time before and after the interview will allow you to write notes, reflect on impressions, and jot down questions.

4. Try these phrases Prepare strategies to control interviews, especially with extroverted applicants. Become comfortable with gentle interruptions. For example, you might say, “That’s great, I have a few more questions I want to get in . . .” Or when trying to keep things moving, you can introduce your questions with “Can you briefly tell me . . .” or “In a couple of sentences . . .”

5. Use paraphrasing Reflecting back what you heard gives candidates a chance to modify or validate what they said. Introverts and extroverts will appreciate the chance to clarify their thoughts more completely.

Understand Your Team

So, you have put your team in place, or, you have inherited a team. First, get a handle on the styles, skill sets, and other preferences of those you will be supervising. If you have been promoted from within the group, you might already have these insights.

Give Everyone Time to Prepare

Chuck, a project manager, described how he prepares for working with introverts. When he creates the right environment, he says, “There is no difference in performance between extroverts and introverts.” He changes his style somewhat with introverts, however, spending “a few minutes creating a short but very clear request or description of the problem.” After presenting it to those managers and giving them a timeframe for a solution, he walks away. This allows the more introverted managers on Chuck’s team to internalize the challenge, process information, and deliver an answer without feeling they must come up with a response on the spot. He also has started using that approach successfully with extroverted managers so they don’t give him “the first answer that comes to their minds.”

Jia, an introverted leader, shares that the extrovert’s propensity for winging it doesn’t always yield the best results. She finds great power in the pause and believes it results in more well-crafted ideas. Jia applies it in meetings by giving her team a “think break” when she senses energy is getting depleted. As an introvert herself, she is sensitive to this shift in the atmosphere. She reads the signs for when a break is necessary, which allows the introverts to process the stimuli coming at them. Everyone comes back with clearer minds, refreshed and recharged.

Style Counts

As an introverted leader, your preparation strength allows you to consider how you will approach people. For instance, let’s say you want to get your team on board with a big project. Shana focuses on facts and details. Aziz listens for the big picture and wants to connect the dots. Knowing these differences can help you discuss ideas and assignments in a way that is most meaningful for each employee. You would describe the project with lots of detail for Shana, and draw big picture themes for Aziz.

Whether you are leading a cross-functional or intact team, knowing who tips toward the introvert or extrovert side of the spectrum is also useful. As mentioned earlier, introverts want time to prepare, quiet periods during the day, privacy, and a slower pace. Extroverts need chances to talk it out, including drop-in social time. Look for opportunities to put extroverts in people-interfacing positions where they can shine. Consider scheduling occasional face-to-face time or video conferences, as Rachel, the introverted finance director mentioned earlier, did, so your extroverts don’t deflate (see page 33).

Also, think about having open-ended, “How’s your mama?” rapport-building questions at the ready (see Chapter 4, Leading People and Projects) such as “What has been keeping you busy lately?” “How did you relax this weekend?” “What did you accomplish this week?” or “What good things happened to you this week?” Such questions help you connect with people when those opportunities present themselves.

Create the Environment

Look around your workplace. Is it bustling and noisy? Or is it more quiet and laid back? How does it suit your need to recharge and be creative? Are there opportunities to engage with others in a way that is not intrusive? An increasing amount of evidence indicates that introverts have sensitivity to louder, Type-A work-places. Consider that it may be possible for you to design an introvert-friendly environment that brings out the best in everyone.

Here are four ideas that may provide inspiration:

1. Multi-purpose spaces Provide multi-purpose spaces that offer a combination of conversation pits, solitary, and public spaces. Have community tables for low-key conversations. Offer “huddle rooms” for conference calls and other meetings. At the company Hallmark, a long table is used not only for meetings and collaboration but also as an open-to-talk signal. In this company, if you’re at your desk, you’re not up for conversation. If you sit at the table, you’re fair game.20

2. Natural mingling For introverts who tend to stay in their comfort zones and don’t see the need to mingle, a central area for breaks can encourage spontaneous conversation. Steve Jobs, while working at Pixar, put two bathrooms in a central location to encourage employees to mingle. Employees tell their “bathroom stories” of creative ideas sparked while washing their hands next to a person they might not otherwise have spoken to.21 By paying attention to physical space, you allow introverts to naturally mingle with the extroverts who thrive on this people time.

3. The sensory environment The sensory environment is also worth your attention. Can you create space that facilitates calm, for thinking and reflecting? Consider lighting and sound in the work space. Bright lights and loud noises may make it hard for introverts to focus. This also applies to meetings and training sessions.

4. Remote work options Offer remote work options to help workers save commuting time and get breaks away from people. Introverts may especially appreciate being given choices to work at home or off site. It can be a part-time or full-time option based on your company’s workflow. If it’s not practical to offer this consistently, explore it on an as-needed basis when introverts need to dig into projects and do deep thinking.

Presence

Being present with people and projects is an essential part of being an introverted leader. Here are some key strategies to build on your quiet strength as you practice presence:

• Walk around.

• Write it down.

• Listen like a leader.

• Have spontaneous conversations.

• Pay attention to facial expressions.

• Flex your style.

Walk Around

A management strategy that gained popularity in the ’80s was MBWA—Management By Walking Around. The idea was to encourage managers to get out of their offices and engage with people. With so many complex distractions in today’s work environment, it can feel daunting to take the time to be visible. But even if you must schedule it on your calendar, talking to the people who work with you can have tremendous payoffs in trust and clear communication.

Bob Quinn is an introverted HR manager who believes in respect and inclusion. He has a daily practice of walking around and talking with people. When Bob oversaw a merger, he met with each affected person and listened to their concerns. He also spoke with top managers and designed an integrated team from scratch.

“By the day of the merger, everyone knew exactly what they would be doing,” Bob said. He also arranged for brunches to take place in each office, gave each new associate a bottle of wine, and appointed buddies to help the newly integrated employees understand the existing culture. “I received some of the nicest thank-you notes that I have ever received from the people who chose to [leave after the merger].” Bob knew things were going well, he said, when a formerly hostile mid-level manager who was leaving the company told him: “You’re not so bad.”

Write It Down

Jon, my former boss, combined preparation and presence by creating a conversational aid. He carried index cards with the name of each direct report written at the top. During the week, he wrote feedback, questions, and ideas, using his lists as an agenda as he stopped in to chat with each of us. We kidded Jon about being obsessive, but we were each intensely interested to know what he had written on our cards! He was prepared for productive conversations, and by being present, he recognized us. We all knew that our work mattered to Jon.

A successful introverted program manager recommends recording the names of people you compliment and the frequency. What is measured is often what gets done, so it will likely increase the amount of positive feedback you give. If you cringe at the idea of spontaneous, face-to-face meetings, write down your talking points. You will feel more prepared and establish presence with those you lead.

Listen Like a Leader

The ability to be truly present with another person is one of the marks of effective leadership, and introverts shine at building one-on-one connections. Can you remember a time someone asked about your life and your work concerns in a sincere and genuine way? When that person listened to your answer, did you feel as if you were the only one in the room? People rarely get the chance to be truly listened to. And when you do that, you exhibit presence in a powerful way.

Scott, an introverted director of business development, says that because he harnesses the power of listening, people open to him “without hesitation.” He is reserved and quiet, which allows him to gather information easily, ask pointed questions, analyze the answers, and articulate a direction at the opportune time.

Have Spontaneous Conversations

In a time when everyone is looking down at their smart phones, spontaneous conversations are becoming less frequent. But when you engage with people, you can learn so much and reap benefits you never would have imagined. For instance, during a flight, I sat next to a man who works as a ticketing manager for a theater in Atlanta, Georgia, my hometown. We chatted about acts we had seen there, and he told me he oversaw ticket sales. Several months later, I watched my favorite dance company perform, thanks to my new friend’s generous gift of house seats. Random conversations can lead to tangible results, and you will inevitably learn something.

Another example: After I gave a speech at the American Library Association, I received an email from a woman named Beth, a self-described introvert. In my speech, I had talked about how much we can learn from spontaneous, focused conversations. Beth wrote:

Vegas (where the convention was held) was a hard town to be in as an introvert. That night, as I hailed a cab, I was overly tired and just wanted to get to the hotel and away from the crush of people. . . . The cabbie started talking with me, something I generally avoid. But I thought about practicing engaged listening and decided I would try it. It turns out, we had an amazing conversation about the educational system in Nevada.

Beth was grateful she took the time to listen and learn from this extroverted driver.

Pay Attention to Facial Expressions

Communicating with Your Face

Consider the story of Nelson Mandela, the great South African leader. What he consistently did in every setting was break out his huge smile. This symbolized his lack of bitterness toward white South Africans and communicated hope and triumph to black voters. Mandela’s smile was his message.22

Like it or not, people read our faces more than they listen to our words, and they are not even aware of the weight they are putting on this aspect of our message.

Rasheka is a woman I admire. She is bright, insightful, and always pulls her weight. But once I was sitting in a meeting with her and thought, if looks could kill, she was committing murder. She had a flat expression on her face the entire time. I am sure Rasheka’s intention was not to be off-putting; but unfairly or not, I judged her as not approachable. If she had offered an occasional nod or slight smile, Rasheka would have projected accessibility, closing the perception gap discussed in Chapter 1.

An important leadership skill is knowing when to step into certain behaviors in certain situations. Many introverts are excellent at doing this. Maybe Rasheka didn’t care about the impact her expressionless face had in that meeting. But in conversing with her team, she would want to consciously turn on more emotion at times so they can connect with her in some way.

Research has shown that introverts tend to communicate apprehension more than extroverts.23 According to several studies, people with communication apprehension can be perceived as more distant, submissive, and indifferent by the people they speak to. This external assessment by others is supported by nonverbal signals, such as body language. Touching oneself, hiding one’s face, and a closed body posture could be such indicators.24 This could inadvertently become a disadvantage for introverts in everyday communication and lead to misinterpretation by others. “Due to this, it is especially important for introverts to read body language of their conversational partner precisely, to recognize miscommunication early and react appropriately,” suggests author Dirk W. Eilert, of Germany, an expert in facial expressions.25

Reading Facial Expressions

In addition to awareness of the image you are projecting, it can be advantageous to become adept at reading others’ faces and to recognize subtle facial expressions. Introverted leaders often tell me that they prefer video conferences over audio conferences. Why? Because they can read facial expressions, which gives them clues into how others are thinking. Voice alone is not as revealing to them.

Dirk Eilert explains that the facial muscles are directly connected to our brain’s emotion center. Facial signals reliably show how someone is feeling through movements called micro expressions. These occur unconsciously and give indication of emotions and objections, which the person is not yet aware of or which are supposed to be hidden. However, he says, we can learn to recognize these, and in his work he teaches people how to do this.

Leaders working with culturally diverse groups can also benefit from reading facial expressions. If you see a person smiling and you think they are not happy, you can probe or observe to better understand what is really going on. Or, in another instance you might say, “You look confused. Am I reading your expression correctly?”

Flex Your Style

Observe to Make Decisions

Along with attending to facial expressions, you can use your introvert strength of observation to know when plans need to change. Bruce, a laid-back software engineer watched his boss, Derrick, do this at a big Singapore trade show. Bruce’s job assignment was to chat up visitors who stopped by the booth and then turn them over to Derrick to close the sale. But Bruce’s conversations with those who stopped by were losing momentum. The questions he had prepared went only so far, and people moved on to other booths.

His boss made a wise, in-the-moment decision. Derrick switched positions with Bruce and became the greeter, bringing his “catches” back to Bruce, who was good at answering most of the technical questions. By making this move on the fly, Derrick saved the situation and gathered potential prospects. Derrick and Bruce worked together to successfully nail a few big accounts. In my book The Genius of Opposites, I call this phenomenon Cast the Character, which means you place the right person in the right role.

What Rewards Do People Want?

Not all team members want to receive kudos in the same way. Knowing people’s preferences for rewards is helpful. So how do you know what they prefer?

Extroverts, who thrive on people energy, might like comments you make to them in front of the group. Introverts, however, might prefer less visibility, like a quiet off-line comment. One introverted researcher I partnered with shunned public recognition but requested I send an email to his boss and the senior leaders on his team. That still got him the kudos with the people who counted.

Push

In amplifying your leadership strengths, you can address one change at a time. Consider reviewing the responses to your assessment in Chapter 3 and decide which area can give you the most payoff right now. Ask yourself which skill can help you achieve the most important challenges on your plate. Becoming strong at leading people and projects involves building upon what you do naturally with some strategic tools.

Here are three leadership strategies that can push you toward discomfort and growth. Let’s take a look at each of them:

• Be assertive.

• Delegate, delegate, delegate.

• Be open-minded.

Be Assertive

Mary Barra is the CEO of General Motors. As a young engineer, she confronted an assembly worker who directed a wolf whistle in her direction. “What are you doing?” she asked. He was trying to attract her attention, he told her. She requested that in the future he do that by saying “Hi.”26 This simple yet assertive statement resulted in more respectful greetings from him, and according to Barra, the catcalls from other men in the plant diminished. Being an introvert, as Mary Barra is, shouldn’t limit your ability to assert yourself.

Introversion and Assertiveness: A Perfect Combination

Assertiveness is often incorrectly confused with aggressiveness, but assertiveness is characterized by mutual respect and clear, open, and honest communication. Aggressive behavior, on the other hand is disrespectful and shuts people down. Introverts show us that you don’t have to “raise your volume to have a voice,” as author Susan Cain wrote on the cover of Quiet Influence.

For The Genius of Opposites, I studied pairs of workplace introverts and extroverts. My research showed that the introverts’ steady, intentional persistence often made the difference in their success. On one sales team, introverted Brian stood in the back of the room, quietly checking in with prospects and responding to their questions. His louder, extroverted teammate, Audrey, made an exuberant pitch from the stage. Brian was assertive by following up with his key target customers for months and, in some cases, years. He closed most of the deals through his persistence and follow-through.

In a more well-known example, Rosa Parks, the 42-year-old seamstress and civil rights hero, exhibited true assertiveness when she made the decision to go against the law and sit in the white section of the bus in Montgomery, Alabama. Her quiet courage led to a widespread bus boycott that ultimately struck down the segregation laws on buses throughout the land.27

Referring to his low-key role in the popular duo Hall & Oates, introvert Daryl Hall acknowledged his brand of assertiveness and the important role he plays by saying, “You can’t have a sunset without the horizon.”28

Beware the Passive-Aggressive Trap

Because introverts sometimes leave their feelings unexpressed, their anger and frustration can come out sidewise, or not directly. This type of behavior is often termed “passive-aggressive.”

Here are some potential scenarios where passive-aggressive behavior plays out. You might respond to your boss’s request to stay late with the silent treatment or an eye roll. Passive aggression in asking for a raise might include sending a complaint about your large workload in a long, detailed email, without specifically asking for what you want. Finally, if a person takes credit for your work, you might be slow to respond to their requests on future projects.

While passive-aggressive behavior might make you feel momentarily relieved, your goals won’t be accomplished. By returning to an assertive stance—directly saying what you mean and asking for what you want, you have a better chance of getting your needs met.

Setting Boundaries

Being assertive also means setting boundaries. Here are some examples of how to do that:

• The boss wants you to work late for the third time this week. It could be time to say, “No, I can’t because I have commitments at home.”

• Let’s say you believe you deserve a raise. You persist in following up with your “ask” even when turned down the previous quarter.

• When someone takes credit for your work on a project you thank them for highlighting the project and explain to the team what you were proud of having accomplished.

There are countless opportunities to speak up for yourself. Introverts such as GM’s Barra have pushed themselves and developed their skills in this area by practicing and pushing themselves to speak up. It is not always easy. Figure out when it is important to set boundaries and find ways to express yourself that are respectful, yet firm.

Helping Others Assert Themselves

As a leader, being assertive can also be a way to advocate for employees. Melinda Gates, co-chair of the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, makes a point of speaking up in support of female colleagues “when a man restates something that a woman already said or talks over her at a meeting.”29 And she calls herself out when she falls into that behavior herself.

You can also support introverts on your team when they don’t feel comfortable asserting themselves. Bill Stainton, a professional speaker and Emmy Award–winner, was chairing a professional board. He tells the story of failing to ask Lucy, an introverted board member, more about her background and skills. After she finished her board term, he discovered Lucy had a goldmine of expertise in an area that would have been helpful in growing their organization had he known. Bill considered it a large missed opportunity. After that experience, he made it a point to learn more about the strengths of the people he is working with, especially when they don’t freely self-disclose that information.

Delegate, Delegate, Delegate

Delegation can be one of the hardest skills for leaders to master, yet it is probably the most needed. How else can you lead, plan, and coach while holding onto the many tactical aspects of your job? Delegation means matching the right person to the right task, knowing their capabilities, and coaching them through their learning curve.

If you can guide people in the beginning and then back off as they gain mastery, you lighten your load while providing challenges and growth for them. Introverted leaders are particularly well suited to the one-on-one coaching needed to delegate effectively. It takes energy, especially in the beginning of your handoffs, but pays off in the end.

One introverted leader said,

It’s tempting to keep a lot of tasks for myself because the energy required to delegate effectively feels high. But this is a flawed calculation, because if I never delegate, the item will belong to me next time, the time after that, and so on. Failure to delegate requires my energy each time the item arises. So instead, I should calculate how much energy will be saved in the future by equipping others to run with ball.

Resistance to delegation lies under the surface. Each of us has hot buttons that keep us from handing over the keys. What are they? Can you counter these reasons with more productive thinking to get you over the hump? Delegation is a vital tool in your leadership package. Once you do start delegating, you will see so many benefits that you won’t go back to the old ways of taking everything on. Table 4 covers some of the ways to overcoming the hurdles of delegating.

TABLE 4 Delegation Hot Buttons

Reason Not to Delegate |

Your Counterargument |

I don’t want to take the time to train someone else. |

This is an investment with great potential payoffs. The rewards of building confidence in my employees and freeing time for me to focus on what matters is worth the training time. |

They won’t do it the way I do. |

Yes—and they may do it better or just differently. Results are what matter. |

I am still the one responsible for the results. |

Yes—and I can also share positive kudos with my team for a job well done. |

As an introvert, I want to avoid too much talking with people, and delegation involves talking. |

I can space my coaching sessions so I have plenty of time between them. |

Add your own delegation hot button here: |

Add your counterargument here: |

Be Open-Minded

Many people experience discomfort when team members disagree, employees push back, or bosses question ideas. They see conflict as negative. It helps to remember that conflict is natural, necessary, and normal. In fact, creative solutions to problems rarely occur without the tension of dissimilar ideas. For instance, the Wright brothers, inventors of modern air travel, were known to have intense disagreements over the course of their collaboration.

Conflict can be especially challenging between introverts and extroverts. Extroverts often prefer to talk about things when conflict arises, while introverts tend to internalize feelings. Introverts say they need breaks during disagreements and time to process their thoughts and feelings. Extroverts can get jazzed up by dialogue and debate. The Genius of Opposites lays out many practical solutions for working through these style conflicts (especially Chapter 4, Bringing on the Battles).

One unique idea from interviews with these “genius opposites” is the Walk and Talk. Get outside your office and take a walk with the person. Extroverts think aloud, and talking out their ideas while walking helps them gain clarity about their ideas. Introverts tend to respond to the relaxed pace and walking beside people, rather than intensely interacting head-on, as can happen in heated discussions. And a side benefit? You both get exercise!

How Great Leaders Embrace Conflict

Great leaders know that they can gain the trust and confidence of their teams by opening themselves up to hear their concerns and resistance. Our introverted former president, Abraham Lincoln, traveled to Civil War battlefields to visit Union troops, and he held “office hours” in the White House to receive interested citizens and their countless requests.30

Like Lincoln, Anne Mulcahy, former Xerox CEO, knew she could not lead from behind closed office doors. She often went into the field to speak with executives, employees, and, most importantly, customers. “Even though Rome was burning,” she said in a 2006 speech, “people wanted to know the future.”31 Today she is credited with leading a very successful business turnaround.

A willingness to hear different opinions can be used as the lever for productive action. Bob Schack, an introverted vice president of business development, recognizes “a lot of egos and opinions at play” in the workplace, but doesn’t back away from conflict. He often creates “a firestorm” by drafting a straw-man plan that he knows will generate momentum and discussion. After a lot of back and forth, what eventually emerges is consensus and action.

Introverted leaders orchestrate productive dialogue to engage both the introverts and extroverts on their teams. This becomes especially important when managing people from different cultural and ethnic backgrounds, or working across the globe with customers.

One introverted Dutch manager told me that her U.S. team is more sensitive to direct feedback, but her employees in the Netherlands expect her to provide ongoing constructive comments. She must adjust her approach with each group to be effective. Taking these cultural differences into account will enhance your leadership style.

How to Elicit Opposing Views

Like Bob in the earlier example, sometimes leaders need to deliberately elicit opposing views to further fruitful dialogue with those of differing viewpoints. Asking a question like “Can you elaborate on that?” can prompt people to flesh out their thoughts and gives you an opportunity to respond with your own point of view. Dr. Gene Griessman, author of The Achievement Factor, responds calmly to proposals he disagrees with by saying, “That is an intriguing idea. Could you tell me what you think the strength and weaknesses of those strategies are?” Griessman poses the question, “Would you mind if I give you another point of view?” As an introverted leader, your calm demeanor and reasoned questions like these will help to set the tone for a civil conversation.

Practice

People tend to think that it’s the extroverts who engage effortlessly in conversations and give eloquent speeches. But introverts do as well. Introversion, as we know, is not about how social or articulate you are. It’s a preference for how people recharge their energy.

Smart leaders are most transparent and trustworthy when they lead from their natural strengths. Practice the skills that push you, and amplify those that come naturally. It is a magical combination. For introverts, those strengths might be quieter, more measured, and less obvious, but they will be no less effective. As was mentioned earlier, it’s not always the loudest voice in the room that gets results.

Ronnie Wilkins, an executive director of a medical association, wanted to launch a nonprofit organization to provide management services that would support his organization’s scientific mission. The need was there, but Ronnie knew he had to sell the board on creating an additional company. He prepared a carefully outlined memo, finding it easier to have conversations and answer questions once people had a chance to carefully consider his proposal.

Ronnie has had practice in thoughtful analysis, writing, and connecting one-on-one with stakeholders. He had to push himself out of his office to have those discussions but knew it was necessary to reach his goals. Within three months, the new company was up and running. It has helped with employee retention by providing new career opportunities and has exceeded performance expectations. Ronnie got it done quietly.

Surround Yourself with a Support System

Practice by using your natural talents, but also push yourself out of your comfort zone. That can help you strengthen your introverted leadership muscle. Surround yourself with a support system. Even though you value alone time, you can also schedule one-on-ones and communicate in writing with members of your informal advisory board.

No one succeeds alone. A coach, mentor, or experienced team member can give you feedback and foster your leadership development. Don’t be afraid to ask for the training you need to be successful—it’s another good practice strategy. Enrolling in classroom and online seminars can help you practice these skills and gather a variety of helpful views from other participants.

You might find that you have a hidden talent to inspire others. Or you might find that leading people and projects takes too much energy and the risk is not worth the reward. But keep in mind that being an introvert is no reason to avoid stepping up into leadership.

FIGURE 2 The 4 Ps of Leading People and Projects