3

The road to momentum

Vasella’s eureka moment

What does it take to make a CEO jump? Dr. Daniel Vasella, chairman of Novartis, one of the world’s largest pharmaceutical firms, found out in April 1999 when he was handed a report on a new drug developed by his oncology division. The results before his eyes were better than good – they were sensational. Vasella knew this drug would make a difference, not only to his company, but to cancer patients all over the world.

The report that electrified Vasella covered the first phase of research on a product then known as STI571, later renamed Glivec, developed to treat a form of cancer called chronic myelogenous leukaemia, or CML.1

At the time, there were about 40 000 known CML sufferers worldwide, with a life expectancy of just four or five years after diagnosis. Given the high costs involved and the small patient population, a purely financial calculation would have shown that it was not worth developing and producing the drug.

Set against this, the results on Vasella’s desk showed an astonishing 100 per cent efficacy. The drug had real potential to prolong patients’ lives.2

Despite the seemingly small business opportunity provided by the restricted patient population, Vasella made Glivec an urgent priority. He knew that every day before the product was brought to market, lives would be lost. Normally it would take more than a decade to move a new drug from phase one research to launch – 10 years in which patients would continue to die. By engaging employees, customers and important stakeholders to share his passion, Vasella managed to build an internal and external momentum that powered a record-breaking performance. Driven by the power of this momentum, Glivec came to market in less than three years.

The story of Glivec is the story of how the value originated by that drug set Novartis Oncology on the path to becoming a momentum-powered firm.

The momentum-powered firm in action

We saw in the previous chapter that momentum can be created by following a momentum strategy – a coherent set of actions focused on creating the specific conditions needed to produce momentum. But how exactly is that phenomenon brought about? The unique combination of factors that creates exceptional growth is too important to be left to entrepreneurial Darwinism or corporate chance. We need a systematic process to implement a momentum strategy. But what would such a process involve? The story of Glivec gives some clues.

The key point for Glivec was the ‘Eureka moment’ when Dr. Daniel Vasella realized the value potential of this new drug and resolved to follow it all the way through, despite what appeared to be a limited patient population. The value he perceived was wide-ranging: for patients, their families and caregivers, for the medical community at large, and for Novartis – although apparently small in terms of economic potential, it was great in terms of social responsibility and employee pride.

This is a crucial point. Momentum-powered firms focus on key stakeholders and understand that the concept of ‘customer’ is much wider than simply the product purchaser. Vasella knew that the ‘customers’ were not just the people buying the drug. Several stakeholders were involved, each offering something different to the firm. Because he understood the different value that Glivec offered to a wide range of concerned persons, as well as the value that each of these groups offered the firm, he knew that it was his task to engage all these different ‘customers’. Great leaders balance and juggle differing demands by originating value targeted at each separate group in such a way as to engage all of them.3

When Vasella sprang into action, his leadership over the following days and months built the conditions that put the momentum effect into play. He made sure that everyone in the company was aware of the new drug’s importance. The message got across – the Novartis Technical R&D team committed itself to beating senior management’s deadlines, many of them volunteering to work overtime. This was internal momentum at work. ‘We were working day and night with great enthusiasm to exceed our already ambitious production targets,’ one of the team members explained. ‘We knew patients were waiting for the drug to be available. They were even writing letters to the chairman. Several of them were dying every day. We were their only hope.’4

Now momentum from within was joined by momentum from without. End consumers – CML patients condemned to death from an incurable cancer whose only available treatment was ineffective and unpleasant – began writing to Vasella in masses begging to take part in clinical trials. With such a rare condition, it would normally take over three years to recruit enough patients for large-scale trials. Novartis did it in four months.

Key stakeholders helped to build more external momentum. Novartis kept the press constantly informed on the story of what inevitably became known as a new ‘wonder drug’, although Vasella himself was reluctant to use the term lest it raise false hopes. The US Food and Drug Administration approved the drug in just ten weeks – the FDA’s fastest ever sanctioning of a new cancer drug.

By focusing on the needs of key stakeholders, understanding what each valued and what each offered Novartis, Vasella targeted and engaged significant groups beyond the company walls to help him to harness the full power of momentum. It required focus and drive, but most of all it required ambition.

The results momentum can deliver

The power of momentum fuelled Novartis Oncology’s drive to fulfil Glivec’s potential. Its momentum gave it a reputation as one of the most exciting places to work in the field of cancer treatment research. The brightest and best flocked toward the firm where the action was, adding more momentum. For Glivec customers, the value was even greater – they can survive for longer, with a treatment that is more effective and less unpleasant than chemotherapy. In addition to the obvious relief from suffering, this greatly increased the number of patients under treatment. The longer patients survived, the longer they would be buying the drug. On top of which Glivec was approved as treatment for other forms of cancer as well.

In the first chapter, we presented the results of our research into the impact of momentum on groups of large firms, but what of its impact on an individual business? In 2002, analysts had estimated that sales of Glivec would reach $800 000 by 2006. In fact, by 2005 they were already in excess of $2 billion. At the same time, a patient assistance programme was put in place that by 2006 had helped 18 907 needy people in different parts of the world. In India, 99 per cent of patients receive Glivec at no cost.

This wonderful story began with the value that Novartis had originated with the drug and the ambition to realize its full potential. That value and ambition was so strong that it engaged customers, employees and stakeholders to share the passion that pulled Novartis to record-breaking performance with no need to push the drug or spin press releases to a sceptical media. That’s how momentum works. Momentum-powered firms are propelled towards the new efficiency frontier by first gaining traction through powerful momentum design and then boosting their progress through momentum execution. These are the twin engines of momentum. Once these are understood, we can map out the road to momentum.

The twin engines of momentum

In a car, regardless of how powerful the engine is, you need traction before you can start to turn that energy into momentum. Furthermore, your speed and fuel efficiency are hugely influenced by the conditions in which you are travelling.

If driving along a bumpy road, you’ll never maintain the speed you would on a good one because the juddering will constantly check your progress. You’ll burn a lot more fuel trying to get to where you’re going because you have to compensate, both for not having enough grip and for the resistance you encounter. You spend more energy making less progress – you have no momentum.

It’s the same with business momentum. When a firm’s offerings lack power, it must compensate for their lack of instant appeal, for the resistance they encounter. Its managers compensate with extra resources to make up for the offerings’ lack of traction and for the rough surface they meet.

For a business to take the road to momentum, two factors must be in place – traction and movement. These are the conditions under which the momentum effect arises. The first needs a method of designing a product that is so compelling to customers that they will adopt it without having to be convinced with stupendous marketing or sales resources. The second requires all sources of resistance to be removed and all sources of energy to be brought into play, creating a vibrant buzz that keeps the momentum going. The first component we call momentum design and the second is momentum execution. These are the two engines of momentum strategy set out in Figure 3.1.

Figure 3.1 The twin engines of momentum

But how are these two engines linked? What is the connection that turns traction into movement? Through what we call power offers. We introduced the idea of power offers in the previous chapter – they are those offers that are so carefully crafted that customers find them irresistible. The twin engines of momentum strategy are linked at the point where the process of designing a power offer merges with the process of executing that power offer. It is on the strength of the power offer that momentum starts or stutters. That is why great power offers such as the iPod, the Wii, the Prius and the Scion create so much momentum – because they are the core of the twin engines of momentum design and momentum execution, they ignite momentum. The eight elements set out in Figure 3.1 are the conditions that must be in place for the momentum effect to take hold. They contain the power that will produce momentum growth. The procedure of aligning and intensifying them forms the eight steps of the momentum process.

Momentum design

‘Chance favours the prepared mind,’ said biologist Louis Pasteur. Leaders of firms that build momentum are skilled at preparing a corporate mindset that picks up compelling insights, that in turn lead to developing great products. Daniel Vasella and the Glivec story are an example of that. The word ‘compelling’ is central to momentum design. It describes the powerful and irresistible force that the process generates, and it sets the bar ambitiously high. For example, the process of discovery that reveals compelling insights is much more ambitious than the detailed analysis of masses of data that traditional firms carry out. Analysis is good, but an over-reliance on rational calculation – as opposed to exposure to the subjective reality of an individual customer’s world – is deeply limiting and risks missing valuable insights.

For a number of years either side of the millennium, BMW excelled at discovering compelling insights about what really attracted customers. The service levels, design and integrated marketing that marked its customer offerings were the result not of geniuses calculating their way to scientific or engineering discovery but, rather, of the simple act of paying attention to customer needs and spotting trends.5

A prime example was the integration of Apple’s iPod into car stereos. BMW was the first car manufacturer to understand the potential of the iPod, the hottest new music gadget in a generation, introducing it into its new cars in June 2004, a full six months before its nearest competitor. BMW drivers could simply place the iPod in a docking station and operate it through the standard steering wheel and dashboard stereo controls. Many other car manufacturers followed suit throughout 2005, including Volvo, Ferrari and Honda. Significantly, though, it wasn’t until August 2006 that Ford and General Motors caught up and realized that their customers might like it too. Two whole years! How is that possible?6

Such lags occur because firms without momentum tend to rely excessively on analysis of market research. They never come up with ideas like this – their forms probably lacked a tick box asking, ‘On a scale of 1 to 5, how useful would you find an iPod docking station?’ But executives in a firm open to discovery spend time with customers and notice people listening to iPods who ritually remove the earphones when they get into their cars. That’s when the light bulb flashes over their heads with a message, if they like those little things so much outside, wouldn’t they like them even more in their cars? That is customer insight.

You can’t just ask customers what they want. Smart companies must understand customers’ needs better than customers themselves are able or willing to express them. The discovery of compelling insights allows us to comprehend better what drives compelling value. When exploring what it is that customers value, you need to go far beyond the obvious financial and functional needs and work at understanding the deeper human drivers that underlie that value. This touches on customers’ dreams, fantasies and nightmares to reach the essence of their emotions. BMW’s ‘Ultimate Driving Machine’ campaign is a fine example of the impact these insights can have. By focusing on the pleasure of driving with slogans such as ‘measured in smiles per hour’ and ‘live vicariously through no one’, BMW connected strongly with its customers’ self-image and aspirations. The value they presented to their customers was certainly more compelling than that offered by Ford’s more functionally-focused ‘Designed for living – Engineered to last’.

This investigation of customer value is a never-ending process. For instance, BMW and other car manufacturers now face the challenge of discovering the design elements that are becoming of greater value for customers in a new era where an increasing proportion of the population is increasingly concerned by environmental issues.

Using customer insights to comprehend better the deeper drivers of value cuts both ways. In addition to a deep examination of the value that the firm can offer customers, the process of strategic exploration should be applied to the value that customers offer the firm, in a search for what we call compelling equity. Again, this is much more ambitious than mere segmentation studies and other such analyses. Companies can acquire compelling customer equity by deeply understanding not just the obvious long-term direct financial contribution of different customer groups but also other dimensions of equity such as the potential of word-of-mouth recommendations and the impact that opinion leadership can have on employees. Returning to the two marketing taglines from BMW and Ford that we highlighted, ask yourself this: which customers are likely to be worth more – those who see a car as a pleasurable status symbol or those who crave durability first and foremost?

The understanding brought by exploring compelling value and equity helps firms to craft targeted power offers that are much more than mere products. The word ‘power’ here has a double meaning – power with customers and power to generate growth. Obviously, the two are connected – the power with customers provides the traction that generates superior business performance. They balance the compelling value offered to customers with a compelling equity for the firm in return.

Such power offers can be achieved only through an iterative process involving true interactive cooperation between business functions. BMW’s ‘ultimate driving machine’ slogan is a case in point. At the heart of BMW crafting is engineering and design – it is the heritage of the firm, continuously nurtured and developed. But every aspect of BMW must contribute to reinforcing the compelling proposition and the compelling target, including pricing, distribution, advertising, promotions and service. In America, one of the actions that crafted BMW as stylish and fun to drive was an innovative communication via product placement in the 1996 James Bond film GoldenEye. The British secret agent drove the new BMW Z3 in hair-raising chases. This initiative was in the context of the launch of the company’s new model, the Z3 Roadster, but it had an impact on the perceived value of BMW’s entire range. This communication resonated among the firm’s supporters because it cemented the repositioning of BMW from a yuppie status symbol into the ‘ultimate driving machine’. Eight years later, adding an iPod dock to their cars was just one of many iterative improvements of the power offer. It contributed to increasing its value further by associating the cars with a cool and desirable innovation.

Momentum execution

It is extremely rare, even in the context of a power offer, that a new product gets it exactly right the first time around. Offers must be constantly improved and tweaked in the light of customer experience. It is vital for employees at all levels to have the ambition to seek improvement constantly. This is feasible in smart companies because employees will have been made aware of or participated in the crucial early strategic exploration phases of momentum strategy. These early stages are essential to establish the traction that builds momentum. Everything must then be aligned and coherent to create momentum boosters and eradicate momentum killers.

Momentum begins by delivering the power offer to customers, and its first signature is superior customer satisfaction. Firms with momentum create vibrant satisfaction – a state of mind that inspires customers to help boost momentum. This kind of satisfaction leads to vibrant retention and vibrant engagement by customers. Again, like the word ‘compelling’ in the design engine, ‘vibrant’ represents an essential element in the execution process. Momentum execution must vibrate with the resonance of the power offer. Momentum-powered firms set much higher and more ambitious goals for customer satisfaction, retention and engagement than do their momentum-deficient counterparts. The vibrancy of the execution process is what continually boosts momentum.

We will be examining these concepts more deeply in later pages, but as an illustration of satisfaction, retention and engagement, consider Apple’s renaissance since the late 1990s. When the American Customer Satisfaction Index began recording data in the early 1990s, Apple was bottom of the rankings in the computer sector. The turnaround began with the launch of the iMac in 1998. With its smooth curves and iconic ‘Bondi blue’ translucent casing, the iMac was a masterpiece of momentum design. But how effective was the execution of this power offer? Extremely – just two years after the launch of the iMac, Apple’s customer satisfaction ratings had shot up from rock bottom to number three in the sector. By 2004, buoyed by the iPod’s halo effect, Apple had reached number one, where it has remained ever since.7

The customers who Apple targeted with the iMac were affluent and design conscious – people who by their very nature are difficult to retain as they constantly seek the next new thing. But the satisfaction that the iMac created drove exceptional levels of retention, and not just for new versions of the iMac. The iPod, launched in 2001, was snapped up by the very same trend setting design junkies who loved the iMac – people who gave the iPod a level of media visibility that helped propel it to a 70 per cent share of the market for portable music players.

The iMac, iPod and iPhone also neatly demonstrate Apple’s excellence at the most powerful stage of the momentum execution process – vibrant engagement. While some consumers simply enjoy music on their iPod, others are constantly buying the latest model and accessories, downloading the latest iTunes tracks and persuading their friends to do the same. Likewise, some iMac and iPhone users just like them because they look cool, but for many others they symbolize something much deeper and more personal. The first group is just consuming – those in the second are using Apple’s products as vehicles for self-expression and self-actualization.

These committed iPod, iMac and iPhone users are part of a tribe. They take great pleasure in sharing their knowledge and experience – it is where they belong. More importantly, their vibrant engagement persuades others to convert to the Apple family.

Coherently executing a well-designed power offer is the basis of the customer engagement that firms such as Apple achieve. Momentum design starts with the discovery of compelling customer insights – learning about them and understanding them. The whole process of momentum design is iterative – return to Figure 3.1 and note how the arrows go both ways in a constant toing and froing. Traction is transferred through the power offer, the spark that fires momentum. Momentum is then constantly boosted by vibrant levels of satisfaction, retention and engagement.

Thereafter, momentum continually replenishes and reinvigorates the offer. It must be actively managed and maintained, but when it becomes systematic to the way a firm does business, each improvement of the offer creates more customer traction. On and on it goes as momentum flows. Firms that harness the twin engines of momentum strategy – design and execution – remain externally focused, not internally obsessed. It is a cooperative, interactive and iterative process rather than a linear one. It is dynamic and constantly changing. It is never ‘game over’.

Momentum design at Skype

To illustrate our framework for the momentum-powered firm, let’s look at Skype, the Internet telephony company created in 2003 by two young Scandinavians, Niklas Zennström and Janus Friis. After less than three years in business, Skype had 53 million customers. In 2005, it was sold to eBay in a deal worth in excess of $3 billion, an incredible sum to create in 36 months.8 How did Skype manage to create so much value in such a short period of time? Because it originated substantial value for customers and was propelled by momentum. Let us examine how this happened.

Skype offers free voice communication from any computer with a broadband Internet connection to any other computer with a broadband connection. All that is required is for the caller to download and register a piece of software.

Skype’s momentum first derived from its superior understanding of potential customers, in this case broadband users. These compelling insights were the starting point on the journey to vast potential. The key components of momentum design – compelling insights, compelling value, compelling equity and power offer design – are illustrated in Figure 3.2, which is simply the left-hand half of the twin engines model in Figure 3.1, as they apply to Skype.9

Figure 3.2 Momentum design at Skype

Skype’s customers already have access to a higher quality Internet connection in order to speed up their ability to send and receive information. They use keyboard chat services but also need to communicate verbally. Unfortunately, a landline telephone requires equipment and wiring, and occupies additional desk space. And traditional telephony does not allow video transmission, which broadband does. This was the initial insight – the need for a single tool that integrated Internet chat, audio communication and video transmission on the same PC that is used for other tasks.

What do Skype’s customers’ value? Convenient chat, audio and video communication is the starting point. In addition, as computer techies they want reliability and, like all consumers, they value low costs. Intensive Internet users, they also feel connected with the culture of free exchange of information. The word ‘free’ has emotional as well as financial resonance for them. Finally, as communicative people they derive pleasure from sharing the fun of communicating. This is compelling value.

The equity that these customers offer Skype in return may be harder to spot. The product is offered free of charge, so where can Skype extract value? The most obvious way is that customers can be cross-sold additional services.

For example, not all their customers’ friends and family will be willing or able to take calls through a computer. However, Skype’s customers would still like to be able to talk to these non-techies. So in 2004 Skype launched its first revenue-generating service, called SkypeOut. This service lets subscribers place calls from their PCs to landline phones in a large number of countries for about two cents a minute, regardless of where the call is made from or to. Subsequent charged-for products have followed, and Skype has even established partnerships with the manufacturers of headsets and Internet-enabled handsets.10

But there is more than just cross-selling opportunity in Skype’s customer equity. The company’s brilliance in targeting heavy broadband users was in recognizing their special attributes. They are in regular contact with their network of friends, family and colleagues, they are early adopters of new communication products, they are an extremely valuable advertising target, they have taken the power of word of mouth to a new level, and they have networking power. This is compelling equity.

The next step was to integrate that understanding into a superior business model – a power offer. In hindsight, the potential of a business that offers free voice communication, that harnesses customer networks for viral marketing, and that brings in profit by cross-selling charged-for products targeted to the same user group is blindingly obvious. But that is hindsight – it was detailed customer understanding and the ingenuity of Skype’s founders that enabled them to create the power offer that everyone else missed.

The outside-in focus of the process of momentum design means that development of power offers is never-ending. The double-headed arrows in Figure 3.2 express the iterative and interactive nature of the process between its four components. Even when power offers have been created, customer reaction can tell an outside-in focused company more about what customers value and what they are worth. Skype is particularly good at capturing feedback from its users through blogs and web forums. This increased knowledge uncovers yet more compelling insights and the whole engine kicks off again – the value becomes more compelling, the equity greater, and the offer more powerful. Provided the firm remains focused on its customers rather than on itself, this becomes an iterative, never-ending process, building ever more customer traction. On the other hand, if it fails to learn these lessons and does not continue improving its offer to them, the firm is issuing an invitation for somebody else to build on its experience and develop a better offer. It will then lose its momentum just as a new competitor starts to build it.11

Skype’s final piece of genius is in its marketing line: ‘The whole world can talk for free.’ What better way to connect with the Internet generation? The brilliance of that line – the communication of the offer – marks the point where the design of power offers, enabled by the traction that the firm has acquired, meets the execution that is needed to start momentum.

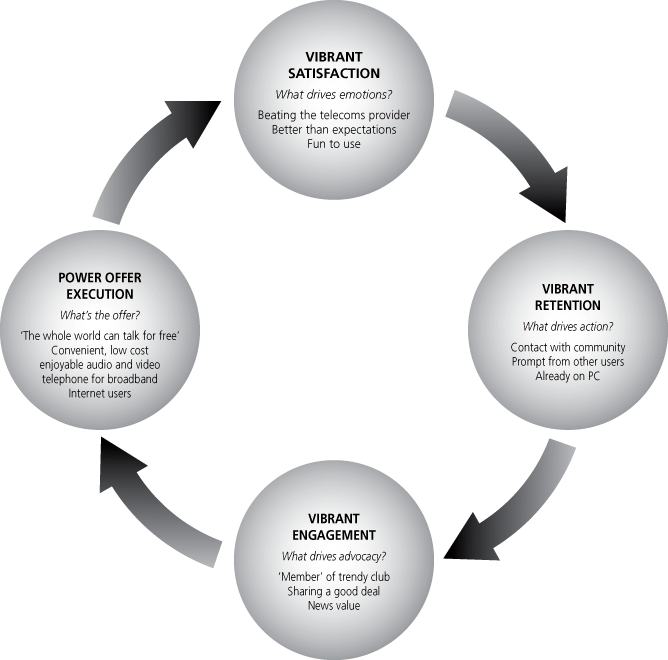

Momentum execution at Skype

The execution of the power offer boosts customer momentum by making the environment surrounding the power offer more favourable through the process of vibrant customer satisfaction, vibrant customer retention, and vibrant customer engagement. This vibrancy is essential and a company must set ambitious goals to analyse, monitor and stimulate these three stages of customer reaction to an offer.

Once Skype designed its power offer, it executed it in such a way that it continually boosted momentum. First, the service was simple to use, easy to install and robust. In short, it delivered on its promise – a telling advantage over many other new technology-based offerings. More importantly, Skype knew that users had felt overcharged by traditional telecoms providers for years, and would doubtless derive satisfaction from breaking free of excessive charges by using the very broadband connection that the telecoms were providing. Satisfaction is an emotional response, and the enjoyment of besting a large corporation, such as a telephone provider, is equal to that of discovering a company that delivers on its promises. The cherry on the cake is that Skype is not limited to just a dumb handset – by donning a cheap headset, the user can simultaneously work or play on his or her PC, examine documents or watch videos. It’s fun. This multiple combination offers more than normal satisfaction. It is a vibrant satisfaction – an emotion so strong that it leads customers to action.

But customer momentum requires much more than satisfaction, even if that satisfaction is more vibrant than normal. Skype ensured that its customers remained active for a number of reasons. First, as broadband users they spent a lot of time on their PCs. Once the firm’s software has been installed, what could be easier than dialling up a friend for a chat using Skype? Alternatively, a friend would be just as likely to initiate a call and prompt the user into remaining an active customer. The dynamics of human interaction kept customers actively using the product. This is vibrant retention, leading to further customer action.

The final step to attaining customer momentum is to secure the advocacy of customers. Because the offering was so good, Skype’s customers actively engaged with it. The principal driving force behind their willingness to engage with it is built into the offer. As soon as people became Skype customers, they had good reason to tell their friends about the service, spreading the news that they could all enjoy free calls together. Being heavy Internet users, they were, almost by definition, in regular contact with their personal networks. Within minutes of signing up they were providing free advertising for Skype. In this manner, each newly signed person played a part in making the customer base grow. These combined boosts to the firm’s momentum brought in approximately 30 000 new users a day through word of mouth in May 2005. By November of the same year it had swollen to around 70 000 a day. Getting people to download software is not that difficult – ensuring that they keep using it is much harder. Here again Skype excels. It first reached 1 million online users in October 2004. One year later, shortly after its sale to eBay, that had grown to 4 million. Less than 15 months after that, the number had grown to 9 million – all actively using a product at any one moment in time. This is more than just the result of casual recommendations. It is vibrant engagement – and momentum that creates exceptional growth.

The process is set out in Figure 3.3, which the reader will recognize as the right-hand side of the twin engines model of Figure 3.1. Note that, as opposed to the illustration of momentum design shown in Figure 3.2, the arrows in the momentum execution diagram all go in the same direction. Whereas momentum design is an iterative process, with each stage feeding back and forth into those on either side of it, momentum execution is a one way force that gathers pace as it builds. The force that momentum generates feeds back into the power offer – in this case, enabling Skype to improve the offer further and thus provide even more momentum boosters by increasing the vibrancy of the satisfaction, retention and engagement. Each stage provides acceleration. Well-executed power offers can generate enormous momentum, giving firms profitable growth with fewer resources. Momentum execution is the second engine of momentum-powered firms.

Figure 3.3 Momentum execution at Skype

Making momentum systematic

It’s no coincidence that smaller entrepreneurial companies such as Skype are more likely to be fuelled by momentum than large, established firms. There are several reasons for this, but if you work in a large organization you will probably recognize the two principal obstacles that stand in your path when it comes to building momentum – complex structures and sheer size.

That is no excuse, though, for a lack of ambition. As Microsoft, Wal-Mart, Nintendo and Toyota show, even the largest of corporations can build and retain momentum for decades. But as Microsoft and Wal-Mart also show, those who have it can lose it if they forget the reasons for this momentum and fail to continuously nuture its source.

What large corporations need to do is systematize the processes that smaller firms manage intuitively. They need frameworks and tools to provide guidance and stimulation to employees in a wide variety of units, locations and levels. They need to learn how to lift their heads, look beyond company walls and connect with the outside world.

That is what we seek to offer in this book’s remaining parts – a systematic approach to guide you, step by step, to momentum performance. Part 2, Designing Momentum, will show how firms setting the bar high can discover compelling insights that lead to compelling value, compelling equity and the design of power offers. Part 3, Executing Momentum, starts with the moment of truth when the power offer meets the customers. We will see how ambitious firms can achieve the vibrant customer satisfaction, retention and engagement that fuel momentum and create exceptional growth.

Momentum-powered firms come in all shapes and sizes, in all sectors and in different times of business history – but the one thing they have in common is a positive ambition. The Momentum League we encountered in the first chapter demonstrated that this ambition is realistic. To take the road to momentum, a firm must realize that unlimited potential for growth lies in originating value from customers. A firm that systematically places customers at the centre of its thinking, and that strives to attain ambitious goals, will be able to harness the power of momentum and deliver the exceptional growth it provides.

The road to momentum is out there. The rewards along the way are enormous. Most importantly, the journey is not the exclusive right of lucky or gifted entrepreneurs – it can be systematically organized, even in the largest and most traditional of firms. It just takes guidance and ambition.