7

Power offer design

A bank that doesn’t like banking

For most day-to-day clients, recommending one’s bank is something like recommending the local tax collector. The easy joke is that they’re both unavoidable, they want your money, they gobble it like Pacman and they leave you with the vaguely disquieting feeling of having been used as a disposable cash cow. Oddly enough, though, there is one bank whose customers like it so much that they have become unpaid cheerleaders – 70 per cent of them recommend it at least once a year. That’s the highest, most enthusiastic approval rate you’ll encounter for a bank anywhere in the world.

Its name? First Direct. This exceptional bank is a remarkable example of momentum created from a standing start. It is a division of HSBC, the leading global financial services company, and was formed in 1989 as a branchless ‘direct’ bank offering telephone-based retail banking services. In an industry as conservative as the British retail banking sector in the 1980s, the idea that people would trust their money to a bank they couldn’t visit staffed by people they couldn’t see, seemed absurd. Yet, less than two years after its inception, it had become the most recommended UK bank – a position it hasn’t lost in the many years since.1

The innovative banking experience that First Direct developed is a demonstration of creating a power offer through the process of momentum design. It is an experience so convenient, easy and enjoyable that it doesn’t seem like banking at all. That’s deliberate, of course, and the company plays on it in its advertising. One recent campaign ran the slogan: ‘Funny. We’re a bank but we don’t like banking. Luckily for us, you probably don’t either. Give us a try.’

First Direct’s power offer, like most others, looks obvious in hindsight but when it was launched, very few people in the industry saw its brilliance. They failed to grasp that it was based on a profound understanding of what certain consumers wanted from a bank, and the potential equity they represented in return. Everything was perfectly lined up for success – a power offer that presented compelling value for a specific customer group that represented compelling equity for the bank – all based on compelling insights.

‘In the UK in the 1980s, to most people banking was tiresome and troublesome,’ explained Alan Hughes, the bank’s CEO from 1999 to 2004. ‘First Direct realized that a bank you could access anytime, without paperwork, queues or hassle was possible, but that alone was not enough. It had to appeal to confident, busy, savvy people intolerant of poor service and inconvenience. So First Direct had to make banking easy and fun. The first First Direct person the customer spoke to had the knowledge and capability to do almost any transaction and they had the self-confidence and the will to make it enjoyable. Of course, that made working there fun, too.’2

This chapter lays out the process that will help firms turn the insights they have acquired into offers of the sort that First Direct generated – power offers that contain within them the energy to ignite the momentum effect and exceptional growth. These offers are designed with ‘power inside’.

What is a power offer?

We know that power offers are at the heart of momentum. They deliver compelling value to customers, who in turn offer compelling equity to the business. Some recent ones are listed in Figure 7.1.

Figure 7.1 Recent power offers

As different as these products and services are, they are all linked because all power offers share one trait – resonance. They resonate with their customers’ needs, wants and emotions while offering their creators superior profit. That grip between compelling value and compelling equity provides the traction that starts momentum.

It is a power offer’s ability to find traction that enables momentum-powered firms – the Pioneers – to surge ahead of their competitors. Their goods and services sell themselves with relative ease – the role of marketing is just to help them reach their full potential. Remember that more than a third of First Direct’s customers joined up on the strength of a 70 per cent recommendation rate.

Power offers are the defining characteristic of momentum-powered firms. They set a whole new benchmark for business. Customers targeted by a power offer perceive it as offering such unquestionable value that they are drawn to it magnetically. The value it carries is so immediately apparent to them, so personal, so resonant, that they feel as though it was designed specially for them. They don’t need to be convinced, persuaded or pushed into making a purchase.3

Power offers are highly efficient. An average, run-of-the-mill offer can, for a short time, be compensated for by high promotional investments but this is an inefficient way of doing business.4 First Direct’s marketing is excellent, but it is secondary to the offer itself. The marketing and communications behind a power offer support the value that the offer delivers but can never substitute for it. Consider the BMW 5 Series. It was named Management Today’s Executive Car of the Year because, as the magazine wrote: ‘BMW’s chief designer, Chris Bangle, has given executives who do not wear ties a car to represent them.’5

The article went on to suggest that the car showed an understanding of customer psychology. It expresses class, quality, achievement and prestige – all aspirations of its core business customers. The BMW 525 is a power offer because of the perception that customers attach to it – that is the source of its momentum.

Beyond the recent examples in Figure 7.1, every positive story in this book has a power offer at its heart.6 The Walkman, the Wii, the iPod, Wal-Mart, Microsoft, IBM, IKEA – all, at some point in time, have been power offers. They were successful because they were appealing to customers and created momentum, pulling their companies to extraordinary, efficient, profitable growth.

Power offers share another characteristic – they look deceptively simple. This is part of their power. All elements of the offer have been carefully crafted, specifically for a targeted customer. They are aligned harmoniously to ensure that nothing jars and that everything is coherent. But coming up with such power offers is not easy. It is the result of long, messy, iterative explorations converging on tough decisions.

Exploring for customer traction

Obviously, power offers aren’t just lying around fully formed, waiting to be found at your feet. Not only must they be assembled with care, but even before that process can start, their components must first be uncovered. This can be done only by firms willing to journey in search of them. The voyage starts with the discovery of compelling insights into unsatisfied customer needs and then plunges into a deeper exploration, searching for further insights into compelling customer value and compelling customer equity. This exploration can be arduous, but it is exciting, eye-opening and fun.

It leads to two parallel and in-depth investigations that reveal how compelling value and compelling equity can be enhanced or destroyed. These insights enable firms to optimize both the value that a customer group will perceive in the offer, and the equity the firm can extract from the customer group being served.

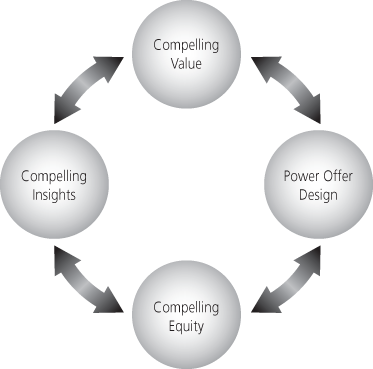

The development of a power offer is a dynamic and iterative process. Like the creation of a sculpture or a poem, the idea for a power offer evolves and is refined over time. This essential dynamism is illustrated in Figure 7.2. The double arrows emphasize the iterations required between the phases of compelling insights, compelling value, compelling equity and power offer design. The process emphasizes exploration centred on the customer and focuses on the value and equity to be transferred by the product rather than the product itself. It is iterative, constantly oscillating between phases in which different functions of the firm collaborate. The net result of this process is the design of a power offer that has sufficient customer traction to produce growth momentum.

Figure 7.2 How momentum design generates customer traction

Power offers are usually the result of a messy, organic maturation – quite unlike the orderly, linear pathways between silos that characterize the traditional product design process of large, established firms. Business success stories rarely dwell on the haphazard stumbles of the early stages of gestation.

The success may appear simple and logical, but the reality behind it is usually complex and chaotic.

Swatch, the Swiss watch manufacturer, is certainly a power offer. Simple accounts of its history often omit the disorderly elements of its evolution and the lessons painfully learned. Swatch as we know it today has evolved from the original idea that launched it. The initial intent was to design a high-quality but low-cost watch made in Switzerland, in order to fight low-cost competition from Asia. Total automation was needed in the manufacturing process, because labour costs were much higher in Switzerland than Asia. This economic necessity led to a simple design and the selection of plastic moulding.

The first Swatch collection was exactly what it was supposed to be – high-quality analogue watches at a low price. They were only black or brown because those were the established colours for watches. Only later, after the first collection, did Swatch come up with the idea of adding colour. Red, yellow and blue Swatches gave the mass market new variety in timekeeping at low cost.

Consumers loved these bright new timepieces. They were innovative and fashionable. Swatch maximized the potential of this favourable reaction, introduced more designs and eventually recruited professional designers. The watches soon became a ‘fashion item that happens to tell time’. With that, the firm changed tack from concentrating on production costs to a focus on design and communication. They switched their initial customer selection – Swatch now targeted not the mass market but, rather, a large group of fashion-conscious younger consumers. This continuous evolution in strategy exploited the progressive discovery of customer insights, customer value enhancers and new sources of customer equity. This unplanned but well-managed iterative discovery process propelled Swatch to its number-one position. That’s the power of momentum.7

From exploration to design of a power offer

The exploration phase of power offer design should be inspiring and rewarding, but managers accustomed to the world of rational analysis can feel uncomfortable with its lack of structure. Working outside the comfort zone of established management practice is something most managers are reluctant to try. This explains why large, established firms miss so many opportunities that entrepreneurs with smaller resources uncover. And this is why the discomfort is necessary – it is the only way to build momentum.

To help managers feel more in control, a simple process is needed to make the transition from the messy, free-form world of exploration to the focused choices that must be made in the final design stages of power offers. Here, the mass of information that the discovery and exploration process uncovers must be distilled into a few key findings. There are two separate but similar paths to be followed. They eventually converge at the point of power offer design but come at it from different angles. The first concentrates on insights that have the greatest impact on customers’ perceptions of value, the second on the ones that relate to the equity those customers offer the firm.

The compelling value path to the power offer

The choices that managers need to make in the design of a power offer can be systematized to a certain extent. Our experience has shown that when managers are exploring – searching for the compelling value inherent in all power offers – opportunities can be easily crystallized by focusing on the four key goals of the process:

- Customer value enhancers – where is the greatest potential for creating value for customers by increasing their perceived benefits?

- Customer value destroyers – where is the greatest potential to create value for customers by decreasing the perceived costs that might lower that value?

- Compelling proposition – what is the value proposition with the greatest resonance?

- Compelling targets – who are the potential customers for whom this value proposition is the most compelling?

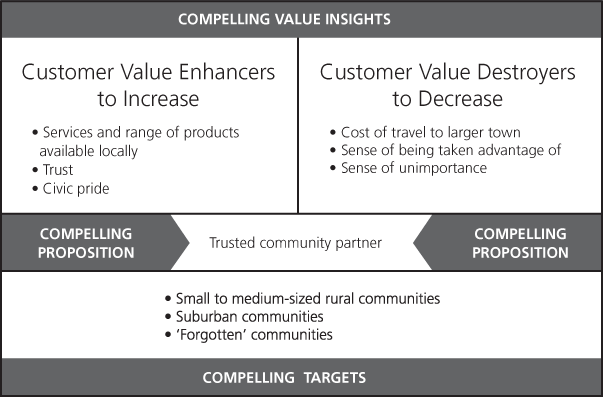

These four questions can be integrated into an action tool, the compelling value path set out in Figure 7.3, building on the insights stemming from the customer value wedge in the exploration phase.8

Figure 7.3 The compelling value path

The two top boxes under compelling-value insights are the results of optimizing compelling value, as discussed at the end of Chapter 5. They should contain a short list of customer value enhancers and destroyers, prioritized for action that will optimize the value perceived by customer groups.

Of particular importance among value destroyers are elements in the design of existing offers that do not resonate with some customer groups but incur business costs. One must chase significant costs from the design of offers currently on the market. Without this ruthlessness, the ability to create value for customers will be limited. Note how Dell and First Direct created power offers by removing a major cost item from current offers, respectively retail trade and branches. In each case, this amounted to around 40 per cent of total costs.

This is what we call ‘cost-out’. Almost inevitably, existing offers will contain expensive elements that do not add to perceived benefits for some customer groups. Removing underperforming elements can free up many interesting options in the design of existing offers by removing the consequent costs. Firms thereby give themselves the option of improving those parts of the offer that do resonate with the customer. This is one of the reasons why momentum strategy delivers greater profitable growth than compensating strategy. Remember – ‘less is more’.

These insights – identifying value enhancers to increase and value destroyers to decrease – show the path to boosting customer value to the point where it becomes compelling for customers. Multiple combinations of these actions are possible corresponding to different value propositions. These value propositions are succinct ways of describing the key value offered to customers. For instance, in the case of a retail operation, alternatives could be ‘guaranteed lowest prices’, ‘your friendly neighbourhood shop’ or ‘convenience anytime’. These three alternatives have different implications, and the first consideration is how compelling customers will find them.

A compelling proposition is the one that has the potential to create a high level of customer traction. To be compelling it must be significantly more attractive to customers than any existing value proposition. This is why it can result only from compelling insights followed by significant changes in customer value enhancers and destroyers.

The middle section of the compelling value path is where one has to select the compelling proposition that has most potential. The other factor that will affect the perceived value of the selected proposition is the customer group at which it is targeted. The process of defining this target begins in the bottom section of the compelling value path.

The key here is to focus only on those customer groups for whom the compelling value offered has the greatest resonance – these are the compelling targets. The process is to actually visualize multiple customer groups and to identify those for whom the perceived value is the highest. At this stage, do not consider the economic dimensions of different customer targets. This will come into play later under compelling equity. Premature concentration on the purely economic side can lead firms to disregard potential targets that may turn out to be more profitable than they first appeared.

To see how all this comes together, consider what the customer value wedge would look like if applied to Wal-Mart’s small-town customers at the time Sam Walton was building the firm. The insights that his exploration of customer value uncovered would certainly have included basic financial and functional considerations – his customers valued greater choice, lower prices and convenience. However, at the more fundamental, intangible and emotional levels he surely uncovered more than that – lack of trust in both big-town commercial centres with their deals that seemed too good to be true, and high-priced local suppliers taking advantage of the lack of competition. Further reflection told him that local people felt slighted that no one deemed their town worthy of a large retail store. In small towns, simple things like trust and community spirit are alive and meaningful.

Such are the insights that might be represented on the customer value wedge. But to turn those basic insights into actions that will build a power offer, we have to ask the four questions above, using the tool set out in Figure 7.3. This helps to map out the compelling value path to power offer design as set out in Figure 7.4. But we’re not home yet – this is only half the story. The next step is to consider the insights gained from an exploration of customer equity.

Figure 7.4 The compelling value path: Wal-Mart, early 1960s to early 1990s

The compelling equity path to the power offer

The process of using the information gleaned in exploring customer equity for the design of a power offer follows the same steps as the search for compelling customer value. They’re symmetrical, but since the exploration is conducted from a different perspective, the principal focus is different.

While compelling customer value involves the trade-off of customers’ perceived costs and benefits, compelling customer equity looks at the balance of the cost to the firm of serving a particular customer group and the benefits that accrue from serving it. Just as different products can either create or destroy value for different types of customers, so too can those different types of customers create or destroy equity for the firm. The point is to optimize the equity that the customers represent.

The four central issues here are:

- Customer equity enhancers – where is the greatest potential for extracting equity for the firm by increasing the business benefits from serving specific customer groups?

- Customer equity destroyers – where is the greatest potential for extracting equity for the firm by decreasing the business costs generated when serving specific customer groups?

- Compelling target – what customer group offers the greatest equity to the firm?

- Compelling propositions – what value propositions have the potential to secure equity from the targeted customer group?

Let’s revisit Dell’s relationship during the 1990s with corporate customers already considered in the previous chapter and apply it to the compelling equity path leading to power offer design. Note that the layout of the compelling equity path in Figure 7.5 is similar to the compelling value path presented in Figure 7.3. The key difference is that the objectives of the central and bottom boxes are inverted – the central box now concentrates on a single source of compelling equity being targeted, and the bottom box reveals a number of value propositions that will be particularly compelling to that targeted equity, rather than the other way around.9

Dell’s initial direct business model, addressed mainly to individual consumers, was a very effective power offer, but the firm soon identified potential growth opportunities with large business customers. The previous two chapters described some of the novel actions the company took in this market, including moving resident engineers to customer sites and pre- loading customer-specific software on the delivered PCs. To penetrate this highly competitive market, Dell’s challenge was to find ways to provide superior customer value in order to generate superior customer equity – it succeeded. On the customer equity side, Dell found ways to increase the benefits derived from customers while decreasing the costs of serving them, as Figure 7.5 illustrates. Dell became perceived as a value partner to business customers who were particularly demanding about getting good value for money from the total cost of their IT equipment, including servicing expenses. Dell generated enormous equity and, with that, momentum-powered growth over many years.

Figure 7.5 The compelling equity path: Dell and corporate customers, 1990s

Some observers claim that Dell was a one-trick pony and that the trick – innovative and effective supply chain management – has now been matched by competitors. This is a very narrow perspective of a much more strategic problem. Dell’s momentum stalled because it failed to continually reinvigorate its power offer both in terms of compelling value and of compelling equity. Dell took its eye off the ball in terms of reliability, quality and service, all key drivers of value, and especially for the more demanding corporate market. It also began to miss a number of emerging sources of compelling equity back in the consumer market, just two of which were digital camera owners and the gaming community.10 Both customer value and customer equity require constant exploration, insights and actions to remain at a compelling level and fuel a power offer.

The pillars of a power offer

The two paths that explore the rich spaces of compelling value and compelling equity meet at the point of the power offer’s design. From different perspectives, each brings qualified options for two key aspects of a power offer – the compelling target and the compelling proposition that will attract them. These different options have to be compared, reconciled and eventually integrated to develop the most powerful offer possible – the offer that simultaneously optimizes customer value and customer equity. Although we talk about a ‘power offer’, we should really think of it as a double power offer – one that provides most value to the customer and most equity to the firm. It is the synergy offered by this double-sided character of power offers that makes them so efficient. The compelling customer value means that customers buy more and for a longer period of time – hence compelling equity. The compelling equity allows the firm to invest more in increasing customer value. It is a virtuous circle that builds more and more momentum.

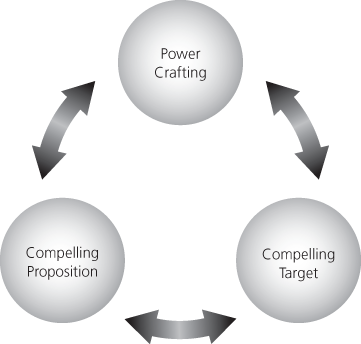

After the key elements stemming from the twin explorations have been reconciled, they must be subjected to the third component of power offer design – power crafting. The existence of this third component has been implicit throughout this chapter. We didn’t make it explicit until now because focusing too early on a power offer’s specifications has a tendency to stop the exploration before all the potential opportunities have been uncovered. This is exactly what happens in many large, established firms. The tendency is to be impatient, to want results fast and to jump on the earliest glimmer of solutions to nail down uncertainties. But the whole process of exploration and convergence must be given adequate time. Only when this process has matured can it move to the power-crafting stage.

To appreciate the scope of power crafting, it is important to remember that a power offer is much more than a product or a service – it is the entire set of elements that influence the value that the targeted customers perceive. A central principle of momentum strategy is that a firm delivers to customers not just a product but value. As a result, power crafting includes technological and operational elements (i.e. possible product specifications), economic considerations (i.e. pricing and the business model) and image (i.e. communication, media and distribution).

An example of how the process differs from traditional design can be seen in the Opel Astra GTC, launched by GM Europe in 2005. The traditional design view was that the three-door model of a car should sell for less than the five-door version – after all, it’s just a five-door car minus two doors so should cost about €500 less. Not the new three-door Astra GTC – it was introduced with a sporty design, great communications, and at the same list price as the five-door version. In fact the average transaction price ended up being close to €2000 more than the five-door version.

Why? Because the crafting of the new design and associated communications created compelling value for a different customer target than had previously been attracted to three-door cars. Its buyers were no longer those people who couldn’t afford a five-door car but a younger, wealthier customer group who liked its sporty looks and image. As a result, they were much more likely to purchase the versions with more powerful engines and additional trim such as alloy wheels and expensive sound systems. All three pillars of power offer design propelled an exceptional growth for the Opel Astra GTC.11

Compelling proposition, compelling target and power crafting are the three pillars of a power offer. As we can see from Figure 7.6, they are intrinsically interactive and the process of designing a power offer involves aligning all three to form a coherent whole. The compelling proposition summarizes what makes a power offer attractive for customers. Its shorthand expression is an inspirational guide that should both connect with customers and drive everyone involved in crafting the offer.

Figure 7.6 The three pillars of a power offer

The compelling target identifies the core customer group to be served in order to maximize equity – for the BMW 5 Series, successful business executives are a customer target with high equity. Again, the customer target should be expressed in shorthand form to serve as an inspirational guide for customers and for anyone involved with the design of the offer, but the key is to remember that it is the compelling equity for which this shorthand stands that is vital.

Finally, power crafting translates the compelling proposition and compelling target into a tangible power offer – developing the intended offer, from its physical appearance to its price, image, delivery and anything else that carries value to customers. Power crafting involves myriad details and can be successful only with the guidance of a clear compelling proposition and compelling target. The sign of excellent crafting is that the compelling proposition and target seem obvious to all those experiencing the offer. Its final objective is to simultaneously produce the superior value and equity that will create customer traction and momentum.

Let’s now review in more detail each of the three pillars of a power offer.

Compelling proposition

A power offer must deliver compelling value to its target customer. This value must be encapsulated in a compelling proposition. This should crystallize, in just a few words, the deepest emotional elements of perceived value – those that drive purchasing behaviour. It may look like a slogan, a unique selling point or a positioning statement, but it is much broader than concepts that focus on communication to customers. The compelling proposition points to the core of the offer. It must simultaneously be attractive to customers and inspire those who craft and deliver the offer. Both, however, must be aware that it is mere shorthand for the richer package of compelling value contained in the offer.

Be it ‘trust’ or ‘community’ for Wal-Mart, ‘fashion’ for Swatch or ‘togetherness’ for the Wii, these words are seldom used in the brand communication of these firms but they are at the core of their compelling value. And they are the key emotional drivers of purchasing behaviour. Wal-Mart has long emphasized its ‘everyday low prices’ – the financial element of the value it delivered to its customers. But behind this very pragmatic communication, the real emotional driver for its core customer group is trust. Beyond low prices, this trust has been established through systematic behaviour demonstrating a genuine care for its customers’ interests. This customer trust is the essence of Wal-Mart. That is its compelling proposition. As such, it is at the heart of the company’s successful momentum growth, and it has to be protected at all costs. If Wal-Mart were to lose this compelling proposition, it would become a different and much less successful company, even if it were still practising ‘everyday low prices’.

Swatch is a ‘fashion accessory that happens to be a watch’. As we described earlier, this strong, resonant compelling proposition of fashion evolved progressively. It took Swatch a long time to discover and crystallize this value proposition. But it clearly marks what kind of customers will probably buy its offers and what the company should expect from them. It is not just a communication promise. It is supported by innovative designs that are being constantly renewed. More than 20 years after its creation, Swatch is still setting new trends and enjoying profitable growth.

Compelling target

A compelling target has two dimensions that are present in all power offers, including those of Rentokil, Dell, SWA, Swatch and First Direct. First, resonance – the fit between the compelling proposition and the compelling target, resulting in a superior perceived customer value – a compelling value. Secondly, the economic significance of the compelling target in terms of the contribution it can make to the profitable growth of the firm – the compelling equity they offer. The two are inextricably linked. If the resonance between the target and the proposition is weak then the economic significance of the target will be correspondingly lower – it will fail to be compelling.

The Swedish furniture firm IKEA is an excellent example of both aspects. Ingvar Kamprad, its eccentric hands-on founder, has always been very clear that IKEA targets people with ‘thin wallets’, as he calls them. For IKEA’s customers, money is more valuable than time. They are prepared to invest their time travelling to the store, getting sucked into its labyrinthine retail environment, and assemble their own furniture in order to save money. A high proportion of them are young couples setting up their first home. This targeting is so effective that it has been estimated that 10 per cent of all Europeans alive today were conceived in IKEA beds!12 This customer selection ties in neatly to IKEA’s key proposition, which is all about democratic design – making intelligently conceived furniture accessible to the masses. The company creates value by passing on some traditional manufacturing costs to its customers – they must assemble their own furniture from flat packs.13

Compelling targets, like compelling propositions, should evolve. Power offers should always be led by economic significance and resonance, and as these change so too must a power offer. Many traditional luxury names such as Gucci, Louis Vuitton and Dunhill were established by catering to aristocrats and the very wealthy. The resonance between these customer groups and the original value proposition of exclusive quality established them as power offers. But the size of these customer groups eventually represented a limit for growth. The success of these luxury goods as power offers was obtained through a progressive extension of the compelling proposition toward fashion and social assertiveness. This caused the targeted audience to grow and become more compelling, offering more growth opportunities and a new momentum.

Power crafting

Power crafting requires every possible design element to be integrated to deliver the highest possible value to targeted customers and extract the highest possible equity for the firm. These elements can concern any aspect, tangible or perceived, of a product or a service. They can be crafted through a variety of means, including technology, design, manufacturing, pricing, packaging, advertising, promotion and distribution. It involves all aspects, both internal and external, that might influence the value of the offer as perceived by customers.

First Direct knew that, as a virtual bank, the quality of its call centre employees’ interaction with its customers was critical. Part of the crafting of its offer was to recruit and train people who sound like human beings rather than automatons. They respond to their caller’s tone of voice and strike the right balance between respect and friendliness. They may engage in spontaneous small talk if appropriate but, if not, they will project an air of calm professionalism and efficiency. Either way, customers’ positive feelings about the bank are reinforced every time they call.14

The following is a slightly edited transcript of a typical conversation between a First Direct customer we’ll call Mr. Scott and a call centre employee.

Mr. Scott: | I’m going skiing in the States. Can you tell me if there is a cash machine in Vail, Colorado please? |

Employee: | I’ll need to ask you to hold the line for a minute while I find that information for you sir. |

Mr. Scott: | Thank you. |

Employee: | Hello, yes, in fact, there is a Cirrus ATM machine at the First Interstate Bank at 38 Redbird Drive in Vail. |

Mr. Scott: | In that case, I’ll only take $500 in cash with me and use the cash machine at the resort. |

Employee: | Right. I’ll put in an order for $500. Shall I debit your checking account and have the currency delivered by registered mail to your home address? |

Mr. Scott: | Yes, please. |

Employee: | Thank you sir. You should receive it within three days. We’ll include a confirmation of the amount deducted. Have a nice trip! |

A few weeks later, the same customer calls First Direct for another transaction. This time it is a different employee who takes the call.

Employee: | Hello, First Direct. How may I help you? |

Mr. Scott: | Good evening. I would like to make a payment to British Gas please. |

Thank you Mr. Scott. I’ll be glad to arrange your payment to British Gas. By the way, were you able to find the First Interstate cash machine in Vail when you were on your skiing holiday in Colorado? I hope everything went well. |

The bank’s advertising states: ‘We always hire people who are naturally approachable and friendly and train them to become bankers. It’s much easier than hiring bankers and training them to be approachable and friendly people.’15 It’s not just a joke at their competitors’ expense – it is an integral part of the power offer and just one example of the excellent power crafting that went into it.

The sheer vastness of the task of power crafting makes it critical that the compelling target and the compelling proposition are fully understood throughout a firm. The crystallized vision of these two elements forms the essential guide for the firm and all its stakeholders to craft a coherent and most effective power offer. This is what underlies the success of First Direct and it is certainly not visible to the outsiders who visit its call centres because they can only ‘see’ the outcome of the crafting. This is also what underlies all the firms we have discussed so far, across a variety of industries, when they enjoyed the momentum generated by power offers, including Dell, Rentokil, SWA, Wal-Mart, Virgin, IKEA, Swatch and Gucci.

The vituous circle of power offer design

A compelling proposition, a compelling target or strong power crafting can often be sufficient alone to make an ordinary product successful. Frequently, one of these three elements lies at the origin of what eventually becomes a power offer. But what creates real momentum growth is the synergy that develops when these three pillars of a power offer are aligned and resonant.

The quality of First Direct’s power offer stems from this level of resonance. Its targeted customers are time hungry, busy, well educated, financially aware and in their early middle years. Apart from the obvious functional and financial drivers of customer value, they are also open to innovation and they value convenience, service and flexibility. They want a personalized and responsive service they can trust. At a more fundamental level, they expect to be treated with respect, and it is respect that is at the core of First Direct’s compelling proposition.

The equity that customers of this sort offer in return is a high level of engagement with anyone who can meet their needs. When it happens, they tend to be pleasant people to do business with. Their high level of financial awareness makes them easy to sell to and unlikely to waste First Direct’s time. Their age, combined with their financial and social profile, means that they are likely to be big consumers of high-value financial services such as mortgages, insurance and investments.

Matching this compelling proposition with an equally compelling target required innovative power crafting across a vast array of components, including call centre technology, employee recruitment and training, customer-focused corporate culture, low-cost operations, intelligent communications, branding and, of course, attractive financial products.16

It is this convergence between compelling proposition, compelling target and power crafting that makes First Direct’s offer so powerful. The three elements feed on one another and the synergy they create is dynamite. Plenty of other telephone and Internet services chewed on the same idea and failed – they weren’t able to come up with a power offer that brought an enthusiastic response. But First Direct got the cocktail just right. Their customers find the bank virtually irresistible.

The almost perfect convergence of a power offer’s three pillars is what makes power offers look obvious after the fact – ‘Why didn’t we think of that?’ But the process of generating such a neat outcome is far from easy, and it is certainly not linear. As we have seen, it first requires exploration to identify new insights that will increase both customer value and customer equity. Compelling value and compelling equity must be contrasted and harmonized to refine a single compelling proposition and its matching compelling target. They then have to be worked through power crafting that will bring new insights for technological and economic realities.

Only an iterative process can create such a strong convergence. Each component influences the other. The selection of a customer target will influence the most appropriate value proposition, and vice versa. Each provides essential guidance for power crafting, which in turn informs, enriches and refines the others. The power of each of these three components must be optimized, and all have to be mutually supportive, coherent and aligned. This always takes multiple iterations with each one getting more compelling and powerful. The idea of a clean, linear process in the development of a power offer is rationalization after the event of a richer and messier process.

Business cemeteries are packed with products that failed to be sufficiently attractive in any of the three pillars. More exploration and optimization on any of them could have saved many and built a strong base for growth. Even more common are products that need inflated marketing budgets to do battle in crowded markets. These products would have more power if their value proposition, customer target and crafting were improved and fine tuned to create resonance. And it is resonance that provides the power for new momentum.

Design for traction

Momentum strategy is about developing power offers that get the customer traction to build momentum. This momentum delivers superior growth while requiring fewer marketing resources than less compelling offers do. As a result, momentum-powered firms can grow with a level of efficiency of which their competitors can only dream.

The design of such power offers is the crucial phase in creating momentum. It is the culmination of the discovery of compelling customer insights, along with the exploration for customer value and customer equity. It stands or falls depending on the quality and coherence of the three pillars – a compelling proposition, a compelling target and power crafting.

These are the guiding principles that we have established for the effective design of power offers.

- Power offers resonate with targeted customer needs so vigorously that they ‘sell themselves’ while simultaneously offering superior profitability to the firm.

- The exploration of customer value should determine the single compelling proposition with the highest potential to deliver compelling value. It will also identify several potentially compelling targets for which that compelling proposition has the most resonance.

- The exploration of customer equity should determine the compelling target that offers the firm the highest potential to extract compelling equity. It will also identify several potentially compelling propositions that have the most resonance for this group.

- Power crafting integrates every possible design element to deliver the highest value to targeted customers and the highest possible equity to the firm.

- Maximum momentum is achieved when a power offer perfectly aligns the three pillars of a compelling proposition, a compelling target and power crafting in such a way as to truly resonate with customers. To achieve this, the design process must be iterative and continuous.

No power offer ever arrives perfectly formed, like Venus emerging from the sea – it takes a lot of tinkering and polishing. All three pillars must be continuously fine tuned, improved and better aligned – tweaking the value proposition, shifting the customer target and improving the crafting. This is the perpetual process of removing any sources of friction that could negate the impact of the power offer and slow the momentum it generates.

The work is not over once the power offer is designed and taken to market. In fact, it has just begun. As we shall see in Part 3, execution of the power offer is itself an iterative process. The lessons learned as the offer is delivered and starts to generate customer momentum can be fed back into the design process to improve the offer’s efficiency and add to the process of discovering compelling customer insights. This is how the perpetual motion of customer momentum begins.