6

Compelling equity

The man who taught an old dog new tricks

Put yourself in the place of someone who has just been appointed CEO of a long established, low-tech firm with a dominant share of a very low growth market. Your potential customers fervently hope that they will never need what you sell. If they do, they are ‘high-maintenance’ clients who delay your agents, bombard them with questions and snoop around their work. They have to be serviced on location, but they tend to be unavailable when you need them during normal working hours, and their addresses are often difficult to find. They are hard negotiators, always looking for special deals. Your new business? An 80-year-old residential pest control company – about as unlikely a candidate for momentum as one could imagine. How confident would you feel about delivering 20 per cent annual growth for 12 years?

That’s what Clive Thompson achieved in the 1980s and ’90s as chief executive of Rentokil, the UK-based international pest control company. When he joined in 1984, he took a look at the business from a fresh perspective. He quickly saw that he could get better value from business customers than Rentokil’s traditional residential market. Rentokil could charge businesses more for one-off treatment against rodents because of the larger sites and companies’ readiness to pay the right price for a quality service. Moreover, business customers were easier to serve because people were present during working hours and more reliable than private customers.

They also offered more long-term potential. A business was more likely to hire Rentokil on a repeat basis to protect its facilities regularly on a yearly or multi-year contract. Large client companies often had several locations, and Rentokil could extend a contract across its different sites. Once accepted as a trusted supplier for pest control, Rentokil could expand into many other services that business customers required, including cleaning, gardening and security. Financially, compared to the one-off fee of about £500 to private customers, revenue per business customer could be tens of thousands for a larger location, hundreds of thousands for annual contracts covering multiple sites, or even million-pound, multi-year contracts for multiple services to a large global customer.

This is what customer equity is all about – a keen eye on the strategic value of customers and taking steps to optimize their value to the company. In Rentokil’s case, this dramatic shift in customer equity generated amazing growth momentum. During Thompson’s tenure, the company was at the top of the Momentum League on a global scale. It became a multi billion-pound outfit and the darling of the stock exchange, and Thompson earned the admiring title ‘Mr. Twenty Percent’. It was so profitable that it eventually acquired a firm twice its size in a hostile takeover, to become Rentokil Initial.1 All of this was driven largely by the shift in focus to a more valuable group of customers.

The concept of compelling equity

Although firms do not own them, customers are a company’s main asset. Indeed, they are more important to a firm than its factories, personnel or brand because they are the point of origin of most of any firm’s cash flow. In the Rentokil example, a client company will bring to the firm a stream of revenues, year after year, as long as the business relationship is maintained. Over the length of this relationship, it will also contribute other benefits, including reputation, references, collaborative product development or the purchase of new products. There will also be various costs involved in serving that client. What this customer is worth in total to the firm, taking into account all benefits and costs over the course of a business relationship, is called customer equity.2 Momentum-powered firms are able to extract superior equity from their customers. They find customers who offer compelling equity – equity that induces the momentum effect.

Again, as with compelling value, the term ‘compelling equity’ is not a meaningless rebranding of other well-known concepts. Compelling equity is about maximizing the value of customers to the firm. Of course, it has to be based on customer targets and market segments, but it has a much stronger intent and meaning. The word ‘equity’ puts the emphasis on what the firm gets from the customers – ‘compelling’ expresses the fact that this equity is so powerful that the firm will have the incentive and potential means to create a power offer that will have customer traction. A compelling equity is thus one of the conditions that is necessary for the momentum effect to take place.

Managers are naturally expected to have a complete and objective understanding of their firm’s assets. Unfortunately, most managers’ understanding of customer equity – the value of a customer to the company – is incomplete and based on subjective perceptions rather than objective reality. As a result, many companies fall into the trap of allocating more resources to demanding customers than to those who represent the highest equity or the greatest potential.

Remember that the process of momentum design involves two interconnected explorations: customer value – what the company offers customers – and customer equity – what it gets back from them. The point of the first is to create compelling value by increasing the attractiveness of the firm’s offer to the customer. With customer equity, we are striving to increase the worth of customers to the firm – we want compelling equity. Stated simply, getting more back.

A product becomes a power offer when it is the source of both compelling value to customers and compelling equity to the firm. A power offer generates exceptional growth because of this combination. It is therefore important that the perceived value delivered to a group of customers should be balanced by the equity they return to the firm. If a company does not provide enough value to customers in line with what these customers are worth, then a competitor will eventually see the opportunity to serve them better and will poach them. Similarly, if a company offers its customers too much value relative to their worth, it will have a negative impact on their profits.

This balance is easily destroyed if management’s perception of customer equity is incomplete or biased. As perception drives action, if the perception is wrong then the corresponding actions will be wrong too. In the previous chapter, we made the point that when it comes to customer value, perception is reality. When it comes to management, it is a different matter! Managers must base their decisions on facts – they must ensure that their perceptions reflect a clear, undistorted understanding of reality.

Transaction myopia

In most firms, management knows all about product profitability but rarely about customer profitability. Even with sensible customer profitability information, management often falls into the trap of transaction myopia when attempting to understand customer equity. This ailment resembles the customer myopia that afflicts most firms when viewing customer value. It occurs because we are biased toward the short-term financial aspects of specific transactions with a customer. Our perception is driven by repetitive events that our memory registers automatically into our subconscious.3 In the case of customer equity, these repeated events are the regular transactions with customers. But the reality of customer equity requires us to appreciate a customer’s worth over the entire length of a relationship. To do so, we need to consciously reflect on and weigh several factors. A perception of customer equity based solely on transactions is inevitably myopic. To comprehend customer equity in depth, we need a broader perspective on the relationship.

Transaction myopia presents several dangers. First, it leads a business to run after any opportunity it can snatch, so long as the anticipated transactions, deals or margins are attractive or, sometimes, even if they are not. This is because financial and psychological incentives are usually transaction-based. Running after individual transactions usually ends up acquiring the exact opposite of compelling equity – dangerously subsidized equity. This is because less profitable customers are inevitably pulled in to drive top-line growth, at the expense of overall profitability.

A simple example of this phenomenon is provided by one of our clients, a leading automobile manufacturer. In an effort to increase sales volume, the company had developed the practice of allowing deep discounts to car rental companies. This was having a doubly negative effect on profit. First, by cutting the margins made on these sales and then by reducing sales of other new cars in six months’ time, as large fleets of lightly used vehicles were released onto the market once the rental companies had finished with them. The company decided to progressively cut the number of cars it sold to the rental sector through the simple expedient of reducing the discount. In the space of two years, although the number of cars it sold to this sector dropped by 20 per cent, the overall margin extracted from those sales increased by more than 50 per cent. Correcting the company’s transaction myopia had increased its customer equity.

Secondly, transaction myopia causes firms, managers and employees to underestimate customer equity. As we shall see, customer equity is a fertile mix of functional, intangible, emotional and financial elements – exactly like customer value.

The Rentokil example illustrates how attractive, non-financial features significantly increased the firm’s customer equity. Rentokil’s traditional private clients often required the service to be offered outside standard office hours and could be difficult to deal with because of the stress of vermin infestations in their homes. Business locations are always open in daytime, so Rentokil’s agents could access the sites easily. Business customers were busy with their own work, so Rentokil agents could get on with their job undisturbed. If they needed help, on-site workers were more likely to pitch in than squeamish home owners. Business customers are more likely to be concerned with results than costs, so Rentokil agents were less likely to get stuck in petty negotiations. Various legal requirements often made services like Rentokil’s mandatory for business concerns. Business addresses in commercial districts were generally easier to find than private homes, so driving time and frustrations were reduced. Commonly, several other potential clients were located in the same business district.

Altogether, then, it was win–win for Rentokil and its newly targeted customers. All the elements of customer equity it experienced – financial, functional, intangible and emotional – form a mirror image of the customer value we discussed in the previous chapter. This symmetry between customer value and customer equity is a constant in momentum-powered firms. Transaction myopia leads to a fixation on just one of these elements – the financial – and even then in a limited and incomplete way. If a firm wants to seek out compelling customer equity, then it must correct its transaction myopia and acquire a clear view of the relationship with customers over time and across all four dimensions of customer equity.

However, let us follow the advice we set out earlier and proceed first to pick some low-hanging fruit. Transaction myopia causes firms to fixate on the financial elements of customer equity, but even here in most cases managers and employees grossly underestimate the true value of a customer. Before investigating the deeper levels of compelling equity, let us look at a basic perspective that can be used to begin to correct transaction myopia – the concept of customer lifetime value.

Lifetime value: the first step in correcting transaction myopia

How can companies begin to determine the worth of their customers? How to estimate equity? Even if incomplete, customer lifetime value can provide an initial estimate. It is the first step in correcting transaction myopia.

The idea of customer lifetime value is very simple. It involves adding up the worth of a customer’s transactions over a lifetime – the period of time we expect to retain him or her. If a customer in a pizzeria spends $10 on a pizza and a Pepsi, what is the equity of offers to the firm?4 What if he’s a regular and visits every week? What if he continues to visit the pizzeria for 10 years before he moves away or stops eating pizza? He’s not worth $10 to the pizzeria – he’s worth $5000 over 10 years. This process is simple, fast and has solid impact. Note that we rounded off the numbers – a simple average transaction, a simple weekly visit and 50 weeks per year instead of 52. This is deliberate, acknowledging the uncertainties inherent in all estimates, but the emphasis remains correct in terms of the purpose of the estimate. Spending too much time on the fine detail provides a false sense of accuracy and loses sight of the purpose.

Like any idea, customer lifetime value can be made far more complex by adding more considerations to improve its accuracy. The most important ones are: Should we consider revenues or profits? What is the right time horizon for the ‘life’ of a customer? Should we adjust for the fact that $1 today is not the same as $1 some years from now? These are all excellent questions and they have technical solutions. But what we suggest as a first stage is to consider revenues over a relevant time horizon of 5 to 10 years and simply add up the numbers.5 Starting from a simple but robust base, one can later refine the process depending on the accuracy needed for any decisions under consideration.

The key purpose of customer lifetime value is to shift from a transaction-based mindset to a customer equity mindset, an essential element for building sustainable, profitable growth. For this purpose, we need a rough estimate of the financial worth of different groups of customers over time. Obviously, the real equity in a customer will depend on our ability to retain him or her, and we will explore this further in a later chapter on retention. For the time being, we are interested in knowing a customer group’s potential equity, assuming that we will deliver the proper value and take other actions to retain him or her.

Using customer lifetime value as the first estimate of customer equity always provides a new business perspective. It helps to escape from the usual focus on transaction size and evaluate the real business opportunities stemming from different customer groups. The small transactions that we tend to neglect can represent enormous opportunities when they are made repeatedly by the same customers. This is how certain firms have corrected their vision of customer equity, made big gains and even transformed their whole industry.

Low-cost airlines are a case in point. Their strategy is usually explained by highlighting the efficiency of their operations. While this is obviously a crucial aspect of their success, they have also exploited the transaction myopia of established airlines that traditionally gave most importance to first class and business class passengers, because of the higher prices and margins.

Consider the success of Southwest Airlines. In the 1970s, when Southwest unveiled its low-fare strategy, the idea seemed at odds with the industry’s conventional wisdom of concentrating on big tickets and long routes. Thirty years later, it is one of the world’s most successful airlines. A short Southwest hop between two intrastate cities might cost about $50, a price that enables people to change their transportation habits and fly much more frequently than before. They will fly to local business meetings, to visit family, to watch a sports event or even to commute between home and office. A commuter on such a route who flies once a week will represent an equity to SWA of about $50 000 over 10 years. Suddenly the numbers begin to look pretty big despite the small value of a single transaction. This compelling equity is one of the drivers behind Southwest’s momentum growth. Airline executives who never took the time to consider this issue would have totally underestimated it. Without such compelling equity, a low-cost airline like Southwest could not survive.

Customer lifetime value is the first step in the journey from transaction myopia to achieving 20/20 vision on customer equity. When kept simple, it is an excellent tool for engaging a wide variety of employees, from top management to the front line. It addresses important questions. Its outcome can be put in simple numbers that can be communicated effectively and strike the imagination. It can create desirable shifts in mindset and in behaviour. But, admittedly, it is incomplete. It needs to be enriched by other considerations in order to reach the total perspective that will build compelling customer equity.

The customer equity wedge

Any customer relationship involves a variety of costs and benefits to business. They must all be fully appreciated before a properly rounded view of the relationship’s worth can be formed. Taking a blinkered view, one that focuses solely on the financial aspects of the relationship, will cause management to underestimate the equity that some customers, such as key opinion leaders, represent and to overestimate the worth of others, such as more arrogant, established customers. Customer equity is the net balance between the benefits customers bring to a company and the costs of serving them.

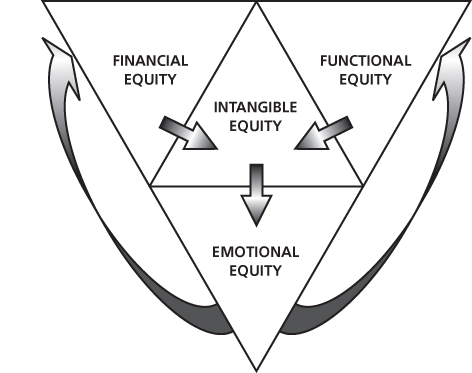

As with customer value, the business costs and benefits that must be considered in forming a view of customer equity include functional, intangible and emotional aspects, in addition to the more obvious financial ones. A useful tool for systematically investigating the elements that influence customer equity is a wedge similar to the one we first encountered in our examination of customer value – in this case reconfigured to form the customer equity wedge, set out in Figure 6.1. It cures transaction myopia in the same way the customer value wedge cures customer myopia.

Figure 6.1 The customer equity wedge

The customer value wedge helped us to explore the different costs and benefits that products and services offer to customers. The customer equity wedge applies the same approach but from a mirror perspective. It helps in investigating the different costs and benefits that accrue to a business in a customer relationship. With the wedge as a tool, one would usually start with the functional and financial elements at the top and go deeper into the intangible and emotional elements, as indicated by the short arrows. As with customer value exercises, brainstorming activities and inspirational examples can be used to elicit a large number of elements until one is satisfied that a complete, in-depth comprehension of the compelling customer equity picture is in place. The longer arrows indicate that in a second stage one must try translating the emotional and intangible elements into functional and financial ones in order to communicate their business impact better. In the end, all these elements will have to be integrated in the two fundamental questions of the business model to serve the considered customer group – How to serve them best? What do we gain from serving them?

The customer equity wedge does not require us to explore the uncharted territory of customers’ hidden mental processes as was the case for customer value, but it does need a dual knowledge of the firm’s operations and customers’ behaviour. The outcome of this process should be the discovery of some insights that will help us to uncover compelling equity.

Financial customer equity

Customer lifetime value is the most appropriate tool for exploring the financial dimensions of customer equity. In the previous pages, we have described this tool merely in terms of revenues, as this is simple and sufficient to pull members of a team away from transaction myopia and to encourage their commitment to building growth through momentum. But to have a more complete financial evaluation of customer equity, this must be complemented by an evaluation of customer lifetime costs and of the net customer lifetime value – the net profits expected over the customer’s lifetime. Other financial considerations can be added depending on the situation, including customer sensitivity to price, payment conditions and other relevant dimensions.

In the Rentokil example, shifting from residential to business customers resulted in a customer lifetime value revenue leap from a few thousand pounds to millions. Furthermore, business customers were relatively less costly to serve and less price sensitive. They presented compelling financial equity on all fronts.

Likewise, although the customers targeted by Nintendo’s Wii are more affluent than traditional gamers, their greatest advantage in terms of financial customer equity is that, unlike dedicated younger gamers, they do not demand cutting-edge performance in speed, graphics or other components. This has enabled Nintendo to make its hardware much more profitable than that of competitors who often sell their equipment at cost and make the profits only on the software.6 The combination of its low manufacturing cost and a new, more affluent profile of its gamers results in a significant increase in its customer equity.

Functional customer equity

The functional elements of customer equity lie at the point where the capabilities of the firm intersect with the needs of its customers. Higher financial equity – in the form of higher prices, higher consumption, cross-selling and higher loyalty – will come only if a firm delivers compelling value to the relevant customers in a cost-effective fashion. But the necessary adaptations to the requirements of those customers may have cost implications that negatively affect customer equity. So the question is this – Where is the best fit between the firm’s capabilities and the value delivered to customers?

SKF is a global leader in ball bearings. A team of SKF managers was searching for industrial customers that might present new growth opportunities. Their insight was to leave behind the mindset of simply peddling more tons of standard ball bearings, and to reconsider the fundamental customer need that their product satisfied. They concentrated their reflections on rotary friction and investigated potential customer groups who were especially concerned with energy wasted through this specific kind of friction. They identified the pulp and paper industry, which uses huge rotating machines to grind wood into pulp, and then pulp into paste, and then paste into paper. Energy is wasted not only because of normal friction in the machinery but also through the secondary operations required to dissipate overheating. Improved ball bearings custom-designed for these heavy machines would allow significant cost savings in both their primary tasks and the secondary cooling. In addition, understanding the enormous cost of downtime in such operations, SKF developed new services such as machinery maintenance contracts with associated performance guarantees. And shifting the perspective from just supplying ball bearings to providing specific customers with a real competitive advantage created growth opportunities for SKF in the pulp and paper sector. The company’s service business became its fastest-growing and most profitable division. By re-examining the functional elements of customer equity in relation to specific clients, SKF was able to increase the equity derived from these customers in a sustainable fashion.7

Intangible customer equity

The intangible elements of customer equity are those that cannot be appreciated as objectively as the financial or functional ones. For instance, some customers may represent different forms of risk that have to be considered because of their financial situation, their geographical location or other reasons. Two examples are automobile manufacturers and construction companies, both subject to economic cycles that create instabilities for their suppliers. A glass manufacturer producing windshields and windows must take this into account in order to adjust the estimation of equity. The same glass manufacturer should realize that the food industry to which it supplies bottles is less cyclical, and this should influence its potential equity positively.

Being a supplier for companies with a reputation for excellence can help in gaining new customers or justifying a price premium for one’s products and services. These special customers have such a reputation of expertise in their fields that their purchasing decisions are observed by others.8 If companies such as GE, Procter & Gamble, FedEx or BMW buy from you then it means that you must excel in your field. This represents additional equity beyond the financial and functional elements.

This is equally true of customers who are loyal, easy to serve or key opinion leaders. Malcolm Gladwell emphasizes this latter element in his remarkable book The Tipping Point. He distinguishes between the ‘mavens’ who have influence and the ‘connectors’ who have access to a network. In the pharmaceutical industry, for instance, leading professors of medicine have a great impact through their research, their presence at conferences and their training of generations of doctors. In a different way, doctors who socialize actively with their peers will also spread the good word when they are impressed with a treatment. They represent equity beyond the financial value of their prescriptions.9

Emotional customer equity

The deeper, less explicit elements of customer equity are emotional. They can create an important gap between the perceived and the real worth of a customer. There are customers who bring important emotional benefits to other customers or to employees, and this should be acknowledged in the way we treat them. On the other hand, sometimes serving certain customers creates such emotional costs that one may consider dropping them.

Some frequently encountered emotional elements of customer equity are displayed in Figure 6.2. In the case of Rentokil, for instance, employees found business clients less difficult to work with than residential customers. In addition, business customers were more prestigious and stimulating to work for.

Figure 6.2 Equity enhancers and equity destroyers

An anecdote involving Virgin Atlantic can illustrate several dimensions of emotional equity. One day at Sydney airport, the airline was forced to cancel a flight to London because of mechanical problems. The announcement was made, and passengers lined up for transfers to other airlines or the next day’s Virgin flight. A passenger near the end of the line began fretting loudly, making noises and generally creating tension. Unable to contain himself, he forced his way to the front of the line and screamed at the desk attendant, demanding an immediate transfer to the next flight. The attendant politely replied that every passenger in line would be served and that his turn would come. Predictably, he resorted to the ancient line of all self-important persons expecting special treatment: ‘Do you know who I am?’ The attendant calmly took the microphone and ad-libbed a public announcement: ‘There is a gentleman here who does not remember who he is. If anybody knows him, please come to Gate 14.’ The entire hall broke into laughter and the irate passenger retreated to the back of the queue.

This incident is rich in learning material about the emotional aspects of customer equity. While exceptional by its public nature, similar situations arise regularly in more discreet fashion. This passenger was creating emotional costs to other passengers and to the staff, and the impact was amplified by the stressful nature of the situation. Satisfying this line-jumper ahead of the others would have caused resentment among dozens of other passengers. The attendant’s spontaneous, witty response satisfied hundreds of passengers at the sole cost of, most likely, one future client. In total, she created customer equity for Virgin.10

An exploration of these four elements – financial, functional, intangible and emotional – opens many avenues that are otherwise hidden by transaction myopia. The concept of customer lifetime value leads the way to this discovery process, but it doesn’t stop there. Firms that examine the deeper reaches of customer equity will be able to target customers that offer compelling equity more effectively and, just as important, avoid customer groups that are potential sources of the friction that slows momentum. As with the exploration of customer value, the process of exploring customer equity should be messy and confusing. Done properly, it should result in long lists of positives and negatives, some of which may initially appear contradictory. The process only really begins to become clear when the results of this exploration are merged with those of the examination of customer value during power offer design. But that is getting ahead of ourselves. For the moment we must, temporarily, accept some uncertainties.

When working with this wedge, note that the location of pertinent factors within each triangle can be somewhat arbitrary, and that these factors can migrate into the space of another element. For instance, if an intangible factor such as risk or the presence of a key opinion leader can be quantified, it could be considered either functional or financial depending on the case. Having a key business leader as a client could be regarded as the equivalent of a $2 million communications budget. That would move this factor from the intangible triangle into the financial. But precise categorization of location is less important than uncovering the various elements that can enhance or destroy customer equity.

The customer equity map

While the customer equity wedge is an in-depth exploration tool for figuring out what benefits different types of customers bring to a firm and the costs of serving them, companies also need a broad, strategic view of the relative equity of these different customer groups – the customer equity map provides this.

The map, shown in Figure 6.3, is a tool for visualizing the total equity that customer groups bring to the firm. Its vertical axis corresponds to the business benefits brought by different groups of customers, while its horizontal axis corresponds to the business costs associated with serving them. The positioning of particular customer groups on this map does not need to be absolutely precise, but it should act like a spotlight to illuminate areas requiring attention.

Figure 6.3 The customer equity map

Customer groups that are on the diagonal sweeping from bottom-left to top-right offer a firm normal equity. This means that they represent a mix of benefits and costs that brings the firm returns in line with expectations. Along this diagonal, they represent balanced combinations that make sense for the firm – increasing business costs are matched by increasing benefits brought by customers. In the bottom-left corner, ‘economy’ customers offer limited benefits but cost little to serve. For Southwest Airlines, for instance, these would be the occasional passengers on the short routes. The mid-range customers provide average levels of benefits in return for average business costs. At the top of the diagonal are premium customers, who bring high benefits but are more expensive to serve.

Given the forces of competition and levels of professional management, one would expect all customer groups to be on this diagonal, but this is obviously not the case. One of the objectives of momentum strategy is to attract customers who bring compelling equity. They would be positioned in the top-left corner of the customer equity map, bringing high benefits at relatively low business costs.11 In the case of Southwest, these would be the regularly commuting passengers. In the case of Rentokil, they would be corporate customers in dense business centres. These are the customers who help create momentum. Competitors will eventually discover the attractiveness of these customers, so the firm must also offer them adequate value in order to retain their equity.

In the bottom-right corner of the customer equity map are customer groups whose cost of service is disproportionate to the benefits they deliver to the firm. Their equity is poor – and possibly even negative – relative to other customer groups. Why do companies continue to do business with them? Because of transaction myopia and an ignorance of the real equity of customers. These customers act as leeches, draining the firm’s resources. They are likely to be attached to the firm because competitors will not make efforts to attract them away. They are, in fact, subsidized by the profits that the company is making from higher equity customers. The negative impact on momentum of these subsidized customers is double – they are a burden on the firm, and they draw resources away from other customer groups who are of strategic importance for the future. It is thus crucial to identify them and to take appropriate actions either to move them toward an acceptable level of equity or to phase them out.

Optimizing customer equity

Momentum-powered firms constantly seek to optimize their customer equity in order to make it truly compelling, to load it with power. To help us in this mission we have presented two tools. The customer equity wedge gives us depth to discover the various elements that influence a customer’s contribution to the firm. The customer equity map gives us the strategic perspective on alternative customer groups. The discoveries stemming from the use of these tools are the ingredients that help to optimize customer equity.

The three paths of customer equity optimization

There are three paths to optimizing the equity inherent in a firm’s customers.

- Chase equity destroyers – identify and prioritize ways of eliminating or reducing the total business costs of serving customers, from financial to emotional ones.

- Build up equity enhancers – identify and prioritize ways to increase the total business benefits from existing or potential customer relationships, from financial to emotional ones.

- Shift customer targeting – identify and prioritize the customer groups that can contribute the highest equity to the firm.

These three paths are not independent. A change in one is likely to have an impact on the other two. This process of iterative exploration is likely to lead to new insights that will reveal previously overlooked sources of customer equity. As mentioned earlier, an important consideration is to avoid focusing on financial issues immediately – this tends to limit the scope of reflection and the resulting insights. The goal is to uncover the less visible dimensions that have escaped the attention of the firm and of its competitors. The most sustainable advantages will be those that are most hidden.

One must not lose sight of a basic fact – ultimate momentum is achieved when an increase in customer equity is balanced by an increase in customer value. The two effects are synergistic. In the previous chapter we described how, over two decades, Dell managed to continuously increase the perceived value it delivered to customers. Let’s now see how the company also exploited the three paths of optimizing customer equity to generate momentum – and how it missed a big opportunity.

Dell started with individual customers but, like Rentokil, soon recognized that developing a presence among business customers could have a positive impact on customer equity. A less visible action was Dell’s decision to move maintenance engineers into key account sites. This increased both the value the company delivered to its customers – better and faster service – and the equity of these customers to Dell. It eliminated the equity destroying business costs of time and money wasted in transportation, while at the same time lowering demand on its own office space. It also built equity enhancers by increasing total business benefits that were often non-financial – resident engineers were spending time with customers and identifying new opportunities. Companies receiving these services became more satisfied, bought more products and services and spread the good word. A significant illustration is Boeing. In the late 1990s, Dell placed 30 engineers in the aerospace company’s commercial division in Seattle. The perceived value of the services they delivered was so great that five years later Dell won a lucrative three-year contract to take over technical support for the computer systems of Boeing’s defence division in St. Louis. The division employed 78 000 persons – that represents fairly compelling equity!

But Dell could have done even better. It took the company two decades to realize that it missed a golden opportunity in terms of customer equity – and Michael Dell even made a public ‘mea culpa’ for the oversight. It concerned printers – these little machines aren’t exactly the noble part of a computer system, but they are a very profitable one. If Dell had offered printers earlier, many customers who bought PCs would have ordered Dell printers at the same time. This would have substantially increased the equity of these customers, both at the time of the transaction and over the whole life of the printer. Instead, Dell left the field wide open to its archrival, Hewlett-Packard. That made a double loss for Dell – in revenue from printer sales and in the customer equity that HP extracted from printers to fund its competitive position in PCs.

These selected elements of Dell’s strategy illustrate the three paths for customer equity optimization as well as the underlying dimensions of the customer equity wedge and the customer equity map. Note in particular the variety of ways in which customer equity is impacted by just the few actions described above – shift to large business customers, resident engineers, service quality, cross-selling, maintenance contracts and the late entry in printers. All these actions were on the top of the core activity of developing, selling and manufacturing PCs, and they contributed significantly to its growth momentum. The challenge, again, is to keep up this momentum. And the solution is to continuously explore the customer equity wedge and the customer equity map to identify new growth opportunities from new or existing customers.

Zero in on customers who drive momentum

Offering compelling value to customers is only half the story. A firm must also be able to extract sufficient equity from those customers to secure a profit. A key driver of momentum is ensuring that the right customers are being served, and in the right manner. Most businesses understand that all customers are not created equal. Momentum-powered firms go beyond that and understand what determines the value of customers to them – they are able to extract compelling customer equity. Momentum-deficient firms are blinded by a transactional myopia that limits their understanding of value to the obvious financial scale of their relationship with customers.

Momentum-powered firms use their broader understanding of customers to take actions that increase the equity of the customers they serve. They build superior customer equity – compelling equity. We have established the following guiding principles to help you do the same.

- Customers really are a firm’s most important ‘asset’, although they are not the traditional balance sheet assets of company property. They must be won and held, and their value must be understood as clearly as that of any other asset.

- Transaction myopia results from the routine of business operations – it affects whole organizations, from top management to the front line. It tends to generally underestimate customer equity and creates a bias toward the most vocal or visible customers, instead of those most important to the firm.

- Average customer lifetime is a first estimate of customer equity. It can help correct an organization’s transaction myopia if used as a leadership tool rather than just as a financial one.

- Acting on customer equity requires a deep understanding of the total business costs and benefits related to serving customers. This will uncover many more growth opportunities hidden by the traditional paradigm of focusing on the financial aspects of customer transactions.

- To remain compelling, customer equity must be continuously optimized by systematically chasing down and eliminating equity destroyers, building up equity enhancers and exploring alternative customer groups.

Different customers, and different ways of serving them, offer differing returns. Building momentum means that those returns must be optimized in order to build compelling customer equity. You have to find the customers that offer the best chances for momentum.

The process of momentum design involves discovering compelling insights that lead to new and unfulfilled sources of compelling customer value and to new and untapped sources of compelling customer equity. These three elements – compelling insights, equity and value – are complementary, interactive and synergistic. They have to be exploited fully to craft products and services that are perceived by customers to be power offers. This is the focus of the next chapter.