5

Compelling value

What women want

Car shows have always been where ‘boys’ toys’ were shown off. It seemed as if the attitude of the men who designed and promoted the cars was that a woman’s proper relationship to a car is to stand next to it and look pretty. And yet, around 80 per cent of all decisions to purchase a car are either made or influenced by women. There is clearly huge potential for any manufacturer who understands what women want.

Volvo’s answer was simple – a car designed for women, by women. The result was the YCC (‘Your Concept Car’), a non-production concept car unveiled at the Geneva International Motor Show in 2004.1

Many of the prototype’s innovative features were amazing – an indentation in the middle of the headrest for ponytails, gull-wing doors for better accessibility, storage space between the front seats, easy-clean paint, an exterior filling point for windshield washer fluid, run-flat tyres, special compartments for umbrellas, keys and coins, and magnetic seat pads that could be removed and changed according to the weather or colour of the driver’s outfit.2

The car got enormously positive reaction at the show, and in subsequent press and online coverage. The insights the Volvo team had discovered had clearly helped them to create compelling new value for both female and male drivers.

However, one of the ideas hatched by the all-female design team didn’t draw the same universal praise – the bonnet over the engine did not open. Reasoning that most drivers open the bonnet only to top up windshield washer fluid, Volvo’s team provided a top-up point for the windshield washers on the exterior of the car and sealed the hood. In fact, the whole front of the car came away in one piece to give better access to the engine, but only a Volvo mechanic could open it. The car was programmed to automatically recognize any problems under the hood and send the information to the garage. Mechanics would then contact the driver and invite her over for the repair.

While most women were happy with the idea that they need never lift a bonnet again, unsurprisingly, others felt insulted. They didn’t want to be deprived of the choice of opening the hood if they so desired. Their perception, expressed on blogs and Internet chat rooms, was that this was an idiot-proof car, patronizingly designed for idiot female drivers.3

This example shows how the discovery of compelling insights can help in creating compelling customer value, but it also illustrates a crucial point – that different people will set different value on any given aspect of a product or service. It is this variation in value perception that creates opportunities for driving profitable growth by presenting specifically targeted compelling value.

What does a customer value? That depends

The focus of this chapter is on understanding how customers perceive value and how firms that understand it can create compelling offers for them. Contrary to appearances, a product does not really drive a company’s success. It is the product’s customer value that does. Products and services are only temporary vehicles to carry value from a firm to its customers. The only reason customers buy products and services is to obtain value.

This concept is best illustrated by imagining some of the different values underlying one industry. Let’s stay with the automobile sector here. Imagine a young lawyer in San Francisco, newly offered a partnership in a prestigious firm, deciding to reward herself for her success. She decides to buy a BMW Z4. In doing so, she could be looking for a variety of different values, including transportation and prestige. In terms of transportation alone, she could buy a bicycle or motorcycle, or walk or use public transport or taxis. Similarly, in terms of gaining the value of prestige, she could purchase a luxury watch, a boat or a painting. All these are competing alternatives to deliver some dimensions of value to this young lawyer. She has just decided that a BMW Z4 carries the most compelling value for her, given her needs at this point in time.

It’s important to note that a product that some customers see as providing strong value will leave others indifferent – some may even perceive it as offering negative value. Consider sport utility vehicles. A suburban mother of three who is also a keen skier might see SUVs as offering extraordinary value that combines important benefits such as safety, power, off-road capability and prestige. She is willing to pay a high price to own one. At the other extreme, a Sierra Club member who organizes her employer’s recycling programme could well find them deeply offensive because of their high fuel consumption, level of pollution and aggressive appearance. She wouldn’t drive one even if she were paid to. Conclusion – a product or service has no intrinsic value, its value is only in the perception of customers.

By using the phrase ‘compelling value’, we are not simply rebranding the commonly used term ‘value proposition’. Compelling value is much more than just a value proposition. If an offer presents compelling value, it will have the potential to create customer traction and will contribute to setting up the conditions needed for the momentum effect to take hold. Just how compelling the value offered is will always be relative – relative to expectations, to competition and to what was offered yesterday. What remains constant is that the question of whether an offer presents compelling value or not depends solely on the customer’s perception of it at any given point in time. Returning to our young lawyer, for her and on this occasion, the value offered by a BMW is seriously compelling – more so than her other options.

This is why optimizing perceived customer value is one of the keys to building momentum.4 It is crucial not only to ensuring the proper design and execution of products, but also to targeting specific customers who perceive the highest value of the offering. When it comes to customer value, firms must understand two things to be effective at compelling design. First, what is the value contained in the offer as seen through the eyes of customers? Second, how can they increase value to targeted customers while simultaneously creating value for the firm?

Customer myopia

Our experience suggests that the growth horizon of large, established firms is restricted by their very narrow view of customer value. We call this condition customer myopia.5 This shortsightedness is caused by the incorrect and distorting assumptions that value is unique, functional and rational. These firms mistakenly believe that truth is unique, that functionality is everything and that rationality is reality.

A case in point is Coca-Cola’s disastrous UK launch of Dasani – bottled water that the company had engineered as rigorously for taste as it had engineered the taste of Coke.6 Yet in the United Kingdom, Dasani became a victim of these three customer myopia traps.

Is truth unique? Momentum-deficient firms believe that value is singular and absolute, when in fact different customers make different evaluations of the same product. In other markets customers agreed with Coca-Cola and took to Dasani – not so in Britain. Same product – different perceptions of value. Truth is not unique.

Is functionality everything? Momentum-deficient firms regard value as a bundle of functional benefits provided to customers at a price, and underestimate the intangible and emotional elements that actually drive customers’ behaviour. Dasani offered a quality drinking water in a bottle. It failed, however, to provide either the health imagery and positive emotions usually associated with bottled water, or the intangible uniqueness of a taste associated with soft drinks. There is more to value than functionality.

Is rationality the same as reality? Momentum-deficient firms extend the scientific concept of rationality to human actions, but in fact customers make decisions based on their perception. Their perception is their reality, and it may be quite different from the ‘rational’ perspective of product-design engineers. Looked at rationally, Dasani offers extra value compared to tap water in several ways. But this was not the perception of the Brits. All they could see was a marketing ploy to repackage tap water at a high price, and they perceived it as an insult to their intelligence. They wouldn’t touch the stuff. Rationality is not the customers’ reality. Their perception is.

These three traps reflect customer myopia and limit the potential of momentum-deficient firms. If they could expand their vision on each of these three elements, a wealth of opportunities to increase customer value would come into focus. There is unlimited potential for companies prepared to correct their customer myopia.

The customer-value map

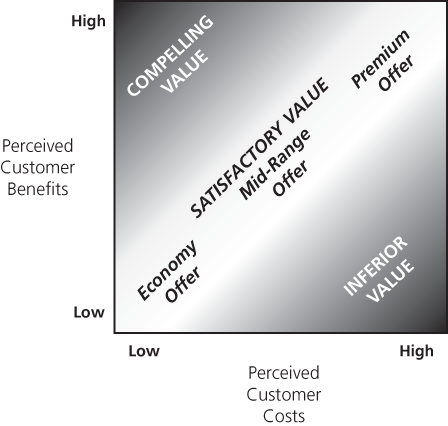

Customers develop their perceptions of value by intuitively trading off perceived benefits against perceived costs. The customer-value map shown in Figure 5.1 is an effective visual tool to represent the strategic impact of this trade-off. It plots where products and services lie in terms of perceived benefits and perceived costs to customers.

Figure 5.1 The customer-value map

The map presents three distinct bands resulting from this trade-off process as indicated by the shading. In the middle, customers perceive that they are given fair offers, while at either extreme they feel either abused or delighted. Where firms place their offers on this map has a major impact on building or losing customer momentum.

The top left-hand corner of the map is the region of compelling value. It is where customers are delighted – perceived customer benefits significantly exceed perceived customer costs. The compelling value on offer there is one of the key drivers of the momentum effect.

At the other extreme, in the bottom right-hand corner, is the region of inferior value. Customers feel that they are abused – they perceive that they are being offered low benefits at high costs. Such products tend to exist because of restricted competition – customers would not buy them if they had a choice. Obviously, these products have no momentum and customers purchase them reluctantly. Companies with such products may make abnormally high margins for a while, but they run a huge risk. When the factors enabling their abuse disappear, as they inevitably will, they will miss the growth opportunities they could have enjoyed with better offerings.

The offerings that result from normal levels of competition are along the middle bottom-left to top-right diagonal of the map. They represent a combination of benefits and costs that is perceived as fair by customers, from a budget range that supplies customers with low benefits but at low costs, all the way up to a premium range that has high benefits but correspondingly high costs.

The customer-value map can help to get a strategic perspective on how industries change through shifts in customer value. In many markets, the base for normal competitive operations sits along the central band. Then new offers appear and provide more perceived benefits with lower costs. They offer compelling value, delight customers and are positioned in the top-left corner. Established businesses lose customers until they react. Then, what was temporarily compelling value becomes standard and a new equilibrium is found until the next innovation.

This is the story of modern business. The momentum effect that stems from superior customer value cannot be produced by a one-shot initiative. Sustaining it requires constant investment in a momentum strategy based on value origination.

Delighting customers

The top left-hand corner of the customer-value map is the position that all new offers should strive to reach – compelling value that creates customer traction. It’s where companies like Virgin and Dell landed at their creation – they understood the strategic importance of delighting customers.

Nintendo is a company that has created enormous momentum by delighting customers. We’ve already mentioned the Wii. Before this breakthrough product computer games were largely the preserve of students, sullen teenagers or their noisy younger siblings – Mum and Dad were tacitly discouraged from picking up the other controller and joining in. Besides, the games – with their repetitive noises, flashing lights, and complex controls – were unappealing or unfathomable to many parents and grandparents. To the mums and dads who usually end up buying them as gifts, they seemed anti-social, increasing the distance between them and their children. The Wii, on the other hand, with its emphasis on movement and togetherness – encapsulated in its slogan ‘Wii would like to play’ – has expanded the gaming market by creating a simple, fun, accessible product that the whole family enjoys. Many of the costs perceived by parents have been removed while a host of new benefits ranging from family fun to moderate exercise have been introduced. So much so that during 2007 the Wii was outselling its competitors by as much as six to one.7

The delight the Wii induces was very evident when we used the product to illustrate a point during a seminar we ran shortly after its release. Within minutes the middle-aged executives on this programme were throwing themselves into virtual tennis and softball, vigorously competing against their colleagues while laughing and whooping. At the end of the demonstration they were all resolving to buy one – ‘for the kids’.

And it is not just the Wii that is powering Nintendo’s momentum. The handheld Nintendo DS is another success story. The console has been a big hit with hard core gamers but Nintendo has also managed to expand the overall market for video games. The ‘shoot ’em up’ or racing style of most computer games does not have widespread appeal with people over 40. If anything, the dexterity and rapid decision-making these games require serves to highlight one’s deteriorating mental and physical agility – something that no one is likely to regard as a benefit.

However, it was exactly this anxiety about failing mental speed and precision that Nintendo tapped into. The Brain Age8 products, based on the books of Professor Ryuta Kawashima, offer a fun way of restoring those intellectual faculties that many feel have dimmed with age. A player takes a series of short mental agility tests9 before the software analyses their results and produces a score in the form of a ‘brain age’. But how does the product delight a 55-year-old that it has pronounced to have a ‘brain age’ of 87? By offering short, fun exercises that ‘train’ the brain and by recording improvements in the player’s score.

Perhaps the greatest customer delight is offered at the moment when players challenge their children and demonstrate that, while they may no longer be able to hold their own on the tennis court, their brain is ‘younger’. For the investment of a few minutes a day on simple and intuitive equipment, players feel they are getting sharper – giving lower perceived costs and enormous perceived benefit. The result? Brain Age is one of the biggest selling games for the DS and the DS itself sold just short of 50 million units in its first two and a half years.10

Abusing customers

At the other end of the scale are companies that provide perceived inferior value. Customers feel abused because they receive benefits that are too low relative to the costs they incur. In the worst cases, this can involve frankly illegal behaviour. For instance, Marsh & McLennan, the world’s largest insurance broker, has been scrutinized for fraud following revelations that its dominance in the sector allowed it to control pricing and the manner in which insurance premiums and payouts were disbursed. The firm was suspected of steering unsuspecting clients to certain insurers. Marsh suffered from a rising tide of defections by its brokers to smaller rivals who, they felt, treated clients more fairly. After New York Attorney General Eliot Spitzer charged Marsh & McLennan’s insurance brokerage with fraud on 13 October 2004, the company lost $11.5 billion, or 48 per cent of its market capitalization, over the next four days. Although customer abuse is often more insidious than in this publicly exposed case, it ultimately destroys business value.

Such abuse often occurs when regulation, high switching costs and other factors restrict competition. Consumers become captives while companies make abnormally high short-term profits. Customer abuse has been prevalent in regulated industries such as financial services, airlines and utilities, but every industry faces the temptation. Market power is a key driver of profitability, and it is an absolutely correct strategy for companies to build market share through organic activities or mergers and acquisitions. But if they exploit market power to abuse customers, they do so at serious risk to their long-term growth potential.

Many large, established companies, including icons such as IBM and Procter & Gamble, have found themselves in situations in which their growth stalled because they took advantage of their dominant position to extract abnormal profits. Customer abuse is inherently an unstable situation. It’s only a matter of time before companies that enjoy its short-term rewards pay a high price for their misdeeds. When disaster eventually strikes, the only beacon that can guide an effective sustainable recovery is to recreate compelling customer value. Giving value to customers, by increasing their perceived benefits and decreasing their perceived costs, is the ultimate guide to creating more value for the firm.

What’s it worth? How customers see value

Customers make trade-offs between perceived benefits and perceived costs to develop a sense of value and to come to an overall decision. The process is based on a subtle balance of factors whose outcome is often surprising.

It’s important to examine customer value through the right lenses – to perceive value as a customer perceives it. Even leading companies renowned for marketing excellence can make massive mistakes if they fail to grasp the intricacies of how customers form their perception of value.

It is all a matter of perception. Fortunately for Coca-Cola, customer perception of Dasani, the bottled water that bombed in Britain, is more favourable in other countries. But its UK reception shows that customers regard value in a far richer, more rounded manner, beyond price and functionality, that involves a multitude of perceived negatives and positives. These can be organized in terms of functional elements (in the case of Dasani, taste, weight and minerals), financial elements (price and delivery cost), intangible elements (carrying pain, social status and storage space) and emotional elements (feeling of being taken advantage of).

In any situation, the systematic exploration of perceived customer costs and benefits must be done in terms of these four structural components – functional, financial, intangible and emotional.

Cost and benefits are perceived by customers as mirror images of each other. The same element can be a cost or a benefit, depending on the value as customers perceive it. For example, the price of a product is usually perceived as a cost but could be perceived as a benefit if it is much lower than similar offers – or, conversely, if it is much higher but this is perceived to add exclusivity. When selecting a laptop, lightweight could generally be perceived as a benefit, but beyond a certain point a customer anxious about the product’s durability may perceive it as a cost.

Creating compelling value by optimizing the value the customer perceives is an essential aspect of creating power offers. A true and deep understanding of customer value enables a firm to unleash many hidden growth opportunities and prevent the sorts of mistakes made with many seemingly well-researched products. To develop this understanding, firms must embark on a systematic exploration of the depths of customer benefits versus customer costs. To do this they need a tool that helps this exploration, a lens to correct their traditional, myopic vision of customer value – that tool is the customer value wedge.

The customer value wedge

Remember the mistaken assumptions that lead to customer myopia – the belief that value is unique, functional and rational. As we have seen, compelling customer value is broader, subtler and more varied. To understand it, one must go deep.

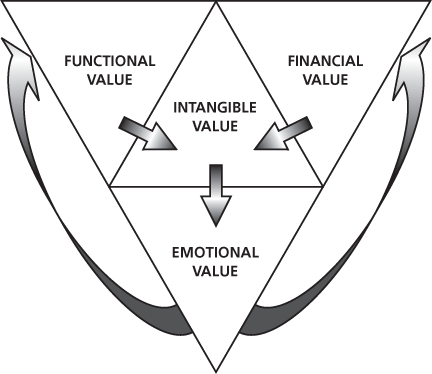

The customer value wedge set out in Figure 5.2 is a valuable tool for creating the right mindset and for investigating the drivers of customer value more thoroughly. Where the customer value map is designed for strategic-level analysis of customer value, the wedge is a more active, everyday tool for building the deep understanding of customer value that will help design and execute a momentum strategy. Its shape evokes a metal wedge for splitting wood or stone to reveal what is inside. In a similar manner, firms need to crack the code of customer value. The wedge’s sharp, downward-facing point contains the deepest emotional elements that are the real drivers of customer value. Ultimately, it is emotions that give rise to actions, even if the real trigger is not always manifest and may be explained away rationally. This is illustrated by the two lateral arrows.

Figure 5.2 The customer value wedge

The customer value wedge contains all four components of value, placed in a way that reflects their visibility from the top down. The functional and financial elements – articulated, rational, easy to see and comprehend – are at the top. In highly competitive markets, these often end up offering no competitive advantage, because they are visible and obvious to all. But the emotional elements that form the point at the bottom – easily overlooked or misunderstood – are the ones that have most impact and bring the big payoff.

Three of the wedge’s triangles have their points facing downward to indicate the need to dig deeper to find the hidden drivers where customer value lies. Even within the more visible functional and financial elements, some aspects of value will always be hidden and require exploration. The intangible element connects the other three. It points upward because, as a general rule, only a tiny portion or aspect of this element – the peak of the ‘intangible’ triangle in the figure – will be visible from the surface. But many broader and deeper ones lie below. Firms need to dig for them.

With the customer value wedge as a tool, you start with the more familiar financial and functional elements of value, move on to the intangible aspects, and then delve into the depths of the emotional drivers of value. The small arrows inside the triangles in Figure 5.2 illustrate this path. Typically, it is best to start by recapping what is known or anticipated about the elements of customer value of a specific product or market. Brainstorming activities and inspirational examples can be used to spark the discovery of less obvious elements and develop a more complete picture.11

The process, which started at the top of the wedge, should become iterative as newly discovered items in one area help stimulate other ideas. Companies should further investigate questions or possibilities emerging from this process and then test them at the customer level via appropriate research. In a final stage, an important task is to translate the key emotional drivers of value into new functional and financial elements that can be communicated in a rational and socially gratifying way.

Using the customer value wedge as a tool mobilizes brainpower to systematically gather the broadest and deepest perspective on customer value for a given product. It builds on all the customer information that a firm has gathered from research and experience, and provides guidance to getting further customer information. Given the financial stakes, it is worth holding regular workshops to use the wedge because it will uncover many insights and avenues of growth through new sources of customer value. These insights and new sources of value are the first ingredients required to fuel customer momentum. This approach is far removed from the dominant customer myopia that considers only the obvious financial and functional aspects of any offer – the superficial layer at the top of the wedge.

Before concluding with some key steps in the process of optimizing perceived customer value, we’ll share a few more helpful hints on each of its four components.

Financial customer value

One of the first symptoms of customer myopia is the belief that price is merely cost, and that this is what counts most in influencing perceived customer value. The myopia is understandable – price is a highly visible, quantitative and comparable item, and customers insist on its importance.

But the purchase price of a product is only one aspect of the financial element of value. Customers consider many other things when they evaluate an offer. For instance, when an airline has to replace part of its fleet, the price of aircraft is only one consideration. Financing facilities, fuel consumption, maintenance costs, price of spare parts, resale value and training pilots and staff are only some of the multiple elements that must be scrutinized just on the financial front. In the end, airlines want an evaluation of the plane’s lifetime cost and the potential return on investment.

The same applies to individual consumers considering the purchase of a computer printer. Many look at the price not only of the printer but of the compatible ink cartridges. Heavy users may calculate that the cost of the cartridges will quickly exceed the price of the printer itself.

Furthermore, in some cases the financial element of comparative customer value may be perceived as a benefit rather than a cost. Some firms sparked a strategic revolution by pioneering low-cost trends that gave them tremendous momentum. This revolution has already affected many industries, including airlines, banking, generic drugs and telecommunications. At the other end of the spectrum, high prices can be perceived as benefits in the luxury goods market. Not only do high prices reflect quality and project social status, they guarantee exclusivity. If Louis Vuitton were to lower its prices, it would lose value for many of its customers. Wealthy consumers love luxury goods because they are inaccessible to the mainstream.12

One of the few infallible laws of business is that customers become smarter over time. Their perspective on financial matters grows more sophisticated and better adapted to their particular situation. The financial value logic of one customer may appear stupid to another, but it is not – it is simply different and specific to a different situation. Trying to reduce this richness of human nature to a simple formula is typical of customer myopia. Understanding this richness allows momentum-powered firms to exploit growth opportunities and build new growth momentum.

Functional customer value

The functional elements of value include physical properties, such as size, weight and performance, as well as features offered. Like financials, functional elements are never totally absent when most firms consider an offering’s customer value. However, there are three symptoms of customer myopia that seriously reduce perspectives of customer value. All of them are quantifiable, and correcting them will create growth opportunities.

The first is the temptation to try to represent their impact on customer value in a rational way and to believe in set, universal rules such as ‘the lighter the better’. In reality, different customers react differently to different properties and features. Great challenges and opportunities lie in understanding these differences.

The second trap lies in regarding functional features only as benefits when in fact customers may see their presence or absence as negatives – i.e. as costs. Some customers, for instance, would never buy a mobile phone that does not include a camera. A product’s most important negative aspect may be not its price but a functional deficiency such as this, for which no price reduction can compensate.

The third trap is the belief that additional features will always increase perceived customer value. In fact, more and more customers perceive complexity as an important cost. For many of them, ‘less is more’.

Intangible customer value

The importance of the intangible elements of value is increasing all the time. Out of the many intangible elements that could be relevant in different situations, let’s briefly discuss three that are becoming crucial in a variety of contexts – risk, time and innovation.

If customers perceive risk in a product, their perception of that product’s value will certainly decline. Suppliers often underestimate this factor. Smart companies can create growth opportunities by providing mechanisms to reduce perceived risk. For instance, leading retailers today offer a no-quibble exchange policy, which reduces customer hesitancy when purchasing gifts or clothing. Many customers will buy three identical skirts in different colours, secure in the knowledge that they can return two after they’ve tried them on at home. In a very different industrial setting, Cemex, the Mexican cement giant, grew from a regional player into a world leader by reducing risk to its customers. It guaranteed its customers delivery within 20 minutes, regardless of weather conditions, aided by satellite and web-based vehicle dispatch technology.13

Time is becoming an increasingly important driver of customer value, and it is perceived as both a cost and a benefit. Whether it is time spent queuing at an understaffed retail outlet or time on the phone waiting to speak to a bank’s call centre, many customers see it as an important cost. Well-planned offers aim to reduce customers’ wasted time by offering them better service, Internet access or other solutions. In contrast, customers in other situations are prepared to spend more time in order to save money. The Swedish furniture retailer IKEA has reduced its products’ price to a low level, so the perceived value increases for customers. IKEA’s customers downplay as a cost the time they invest in assembling their furniture themselves.

Innovation also becomes an increasingly important intangible cost or benefit as customers become smarter and more discriminating. Some customers will pay a premium for an innovative offering because they enjoy change or wish to look trendy. Others are suspicious of innovative solutions, fearing the associated risk and time required to learn and adapt.

Emotional customer value

The emotional elements of customer value are often invisible to the analytical business world. And yet deep emotional drivers, such as fear and pleasure, are often the most powerful reasons behind a customer’s purchase decisions. Indeed, psychological research using brain-scanning technology has demonstrated that people presented with two options will tend to make the wrong choice if the rationally right option is framed in a way that associates it with negative emotions.14

It is important to realize that these emotional drivers play a critical role even in the most rational business environments. For example, in an industrial firm run by engineers, a supposedly rational procurement officer could become an emotional customer if the factory came to a standstill because of delays in delivery resulting from his or her decision.

Lying at the sharp lower tip of the customer value wedge are the deepest emotional drivers, rarely expressed. It is generally easiest to elicit these deep emotional drivers from customers by focusing on the negatives. For instance, the following questions are more likely to elicit insights: What keeps you awake at night? What is your worst nightmare? What was your worst experience as a customer? In contrast, positive questions – such as what is your ideal supplier or dream product? – are usually less effective, although they may elicit revealing responses.

In most instances, these deep emotional drivers relate to personal issues – they are dictated by complex fears and convictions concerning self-image, trust, respect and justice. In the case of commercial customers, they will also include the fear of being fired or the excitement and anticipation of promotion and success. In many business-to-business situations, the ultimate value that a supplier can bring to a firm is a way to help it outperform competition. Because of the intensity of competitive situations, this value is more than rational – it is emotional.

A company needs customers to have positive emotions about its product or service to achieve momentum – emotions drive actions. This can be illustrated by a humorous legend circulated in a multinational firm specializing in pest control. According to this yarn, the head of international development used a simple research technique to test whether a country in which the firm did not yet operate was ready for the firm’s services. Immediately after landing, he would go to eat at a nearby middle-class restaurant. He would wait for the dining room to fill up before taking a cockroach from a box in his pocket and placing it on the floor. When the bug had reached the middle of the room, he would leap up from the table shrieking: ‘A cockroach! A cockroach!’ Then he would observe how the other restaurant customers reacted. If people said, ‘So what, it’s just a cockroach,’ then that country was not ready for the firm. If they were horrified, he knew the company was ready for a new expansion.

The basic value that this firm delivered was hygiene. The cockroach story demonstrated people’s emotions about hygiene. Of course the tale is apocryphal, but it makes a key point to the company’s employees – the key driver of customer value is emotional.

The purpose of the customer value wedge is to find new insights into the financial, functional, intangible and emotional drivers of compelling value by exploring as many avenues as possible. This is likely to be messy and confusing. If you are not confused at some point in your exploration, you are not doing it right! You have stayed in the comfort zone of your current experience and knowledge. Managers instinctively hate confusion, which is why they tend to stay in the comfort zone of tradition and not see all the growth opportunities out there. Getting confused is not only normal but essential for this process – you have to get confused through exploration. What is not normal would be to remain confused! After exploration, you need to sift through what you have discovered and focus on the most compelling elements that will be the base of your strategy.

Let the customer see better value

The customer value wedge is an effective tool for deeply exploring the value drivers of different customer groups. In this exploration, we aim not only at a deeper understanding of these groups but at systematically identifying the many ways of increasing the value they perceive. This is basic stuff – customer-value improvements unveil new growth opportunities.

Microsoft enjoyed the momentum effect for many years – it created superior value for its customers in financial, functional and intangible terms. But it has lost its momentum despite being continuously innovative and bringing multiple new products to the market.15 Why? We have used the customer value wedge to test the reactions of executive users of Microsoft products. We believe that Microsoft’s problems stem principally from perceived emotional costs that, implicitly or explicitly, drive down the perceived customer value of its products and services. In terms of future growth, this has implications worth billions of dollars. The amounts at stake would certainly justify a major programme to systematically identify the sources of these negative emotions in different customer groups, and to install an ambitious vision for injecting positive emotional benefits. It is the curse of many dominant companies to have their growth burdened by customers’ negative emotions. For customers, these negative emotions add to the cost of doing business with the firm, and significantly reduce its products’ perceived value.

A company can significantly improve its offers by exploring with the customer value wedge, gaining improvements in perceived customer value that it had not seen earlier. Providing superior perceived value is a fundamental driver of the momentum effect, and it is essential for an effective momentum strategy. The design of what we call a power offer will be addressed in its own chapter, but let’s see here how the view through the customer value wedge maximizes customer value.

The golden pathway to increased customer value

There are three tracks that, together, form a single broad pathway, glittering with tremendously increased opportunities for the smart company.

- Decrease perceived customer costs – identify and prioritize all avenues to cutting and eliminating perceived customer costs, from financial to emotional ones.

- Increase perceived customer benefits – identify and prioritize all avenues to increase perceived customer benefits, from financial to emotional ones.

- Select customer groups – identify and prioritize the customer groups that perceive the highest value in the resulting offer.

These three paths are not independent or alternative courses of action. They must be explored together and iteratively to develop the best combination offer based on what has been learned from the customer value wedge. Care and reflection are required though – as we have seen, one customer group’s negative can be perceived as a benefit to another. One customer’s improvement can be reduced value for another. In any case, returning frequently to explore these three paths will bring new customer value insights that may have been overlooked in previous investigations with the customer value wedge. Finally, although the emphasis at this stage is on optimizing customer value, we must also keep in mind the final objective of maximizing value creation for the firm. The key challenge is, obviously, to optimize both customer value and business value – not to increase one at the expense of the other.

Let’s illustrate customer value optimization with an example. From its early days, the Dell computer company demonstrated that it had mastered the richness of customer value. Michael Dell built his company by going well beyond the basic, functional benefits-versus-price paradigm then dominating the PC industry.

Michael Dell first realized that the customer benefit of face-to-face interaction with salespeople was weak. The stores were often in inconvenient, out-of-town locations and were usually understaffed by poorly trained salespeople. The whole process was time consuming and frustrating, but the retailers’ high overheads meant that the computers were still relatively expensive. The low perceived benefits and high costs caused young student customers like Dell to feel abused. He searched for a better alternative. By selling direct, he was able to save the 40 per cent retail margin with no noticeable loss in perceived customer benefits. In addition, customized assembly on order, fast delivery and good service provided extra benefits. He had found the way to offer a compelling value to a certain population of customers. These customers went directly from a perception of being abused by other firms to being delighted by Dell.16

Now, consider some other aspects of Dell’s strategy to see how they exploited opportunities for offering even more compelling value and creating momentum. Dell’s business model allowed him to lower inventory from an industry average of 80 days to just a few. Obviously this saves working capital, but how could this create benefits to customers? The answer is speed. Customers like innovation and want to have the latest available PC technology, so many companies invest huge sums in speeding up their innovation cycles – but the traditional distribution system eats up 80 days of inventory time before new models reach their customers. So a low inventory level not only costs less but also allows Dell to get innovations out faster. Again, more gain, less pain.

Dell discovered that its corporate customers’ incurred costs of around $200 to $300 per computer getting their IT departments to install customized software configurations on new PCs. Dell offered its key accounts a simple, valuable solution – Dell would install the customized company software during assembly. By direct connection to a customer’s server, Dell could download onto each new PC’s hard disk the relevant software for its future user at a fraction of the cost of the previous process. Again, more benefits at lower cost.

These same corporate customers are an example of the evolution in the customer groups that Dell selected. Initially, the target market was students like Michael Dell had been himself, with little money but not particularly demanding. As Dell expanded, its customer targets changed to more demanding but more affluent home computer users. Finally Dell began to target corporate customers who were yet more demanding but offered much higher revenue and lower costs in return. These demanding but highly attractive corporate customers ended up accounting for the largest proportion of Dell’s business.

With these and other customer value enhancing solutions, Dell stood as an exemplary momentum-powered firm, rising to top worldwide computer sales. It joined the elite Fortune 500 list of the world’s biggest companies in 1992, and in 2005 Fortune ranked it first in its ‘Most Admired Companies’ list. As always, though, the challenge for any company is to keep the momentum rolling.

An accumulation of challenges hit the company. Its PCs began to appear undifferentiated, customers reported increasing problems with its service support and a number of lawsuits concerning marketing practices hurt customers’ trust in the company. In 2006, two years after Michael Dell stepped down as CEO, the company lost its once substantial lead in the PC business to Hewlett-Packard. Dell became momentum-deficient because it became complacent and neglected to sustain a compelling value for its customers. In January 2007, Michael Dell returned as CEO, carried out a shakeup in top management and embarked on a major turnaround.17

Go deep, be compelling

Momentum-powered firms don’t just offer good customer value to their customers – they offer compelling value. A value so intense and personal that it resonates with those customers’ needs in a grippingly powerful way.

Going beyond the limits of the standard, the acceptable and the average enables momentum-powered firms to uncover insights into customers’ perceptions, and this is what builds compelling value. The only way to create compelling customer value is to transcend standard financial and functional value calculations and truly understand the drivers of perceived customer value, especially those that are veiled, emotional and intangible.

Momentum-deficient firms cannot see the true nature of customer value because they suffer from customer myopia. Their view is restricted and distorted. We have established five guiding principles of compelling customer value to serve as lenses to correct this myopia and uncover growth opportunities.

- Customer value drives business, not products. Customers buy products only in order to obtain the value they offer. Products are only transitory, temporary vehicles to carry value from a firm to its customers.

- A product has no intrinsic, absolute value. Different customers perceive different value from the same product. For some, a product offers immense value. For others, the same product has no value at all or even a negative value. As a result, customer value must be explored from many different perspectives.

- Customer decisions involve a constant trade-off of perceived costs and perceived benefits. Achieving compelling customer value requires a deep understanding of the pain and gain as perceived by customers themselves.

- Perception of value does not follow a universally agreed rationality. Customers may explain their choices in a socially acceptable rational manner, usually in terms of the financial and functional aspects of value. But true customer reasoning is internal, personal and hidden. And its most powerful drivers are often the deep intangible and emotional determinants of value.

- Perceived customer value must be continuously optimized by systematically decreasing customer costs, increasing customer benefits and exploring alternative customer groups.

The customer value map and the customer value wedge are two visual tools that help to implement these principles. They provide a framework to systematically discover opportunities for increasing perceived customer value. The objective is to energize the value delivered in the firm’s offers, as its targeted customers perceive it.

In addition to optimizing perceived customer value, a profitable growth momentum requires simultaneous optimizing of the value of the targeted customers to the firm. This is the focus of the next chapter on compelling equity.