CHAPTER THIRTEEN

ORGANIZATION CHANGE THEORIES AND MODELS

Michael Brazzel

Change is inherent to organizations today—change desired by organization leaders to satisfy goals and accomplish organization visions, change that results from changes in the worldview of organization members, and change that is a response to what is happening in an organization’s external environment. All organizations are continually changing. That is true in business and in other organizations, as well.

This chapter is a review of organization change theories and models that are popular today. Organization change theories are the lenses that are used to understand, explain, and predict organization change. Organization change models are based in change theories. They are used to guide change initiatives and organization responses to change.

Organization Change Theories

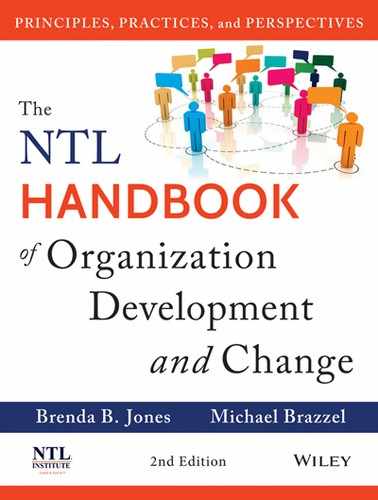

There are multiple theories of organization change. Knowing multiple theories provides different lenses from which to understand, explain, and predict organization change, a variety of comparisons, descriptions, and explanations, and a more robust foundation for creating organization change models. Five change theories are described in this section and listed in Table 13.1.

TABLE 13.1. THEORIES OF ORGANIZATION CHANGE

Sources: Van de Ven and Sun, 2011; Kezar, 2001; and Bushe, 2012.

Adaptive and Unpredictable Change Theory

Change is mostly unplanned. Organizations must adapt to their external environments in order to survive and grow. Their focus is more “change management” than planning for change. Organizations manage change by adapting to emerging external forces. Change unfolds in a largely Darwinian process of competition and survival of the fittest, random chance, self-organization, and selection and retention by leaders of those structures and processes best suited for an environmental niche. Leaders help the organization adapt to external changes for competitive advantage by supporting connection, interaction, and self-organization. The outcome of the adaptive and unplanned change is new structures and processes (Kezar, 2001, p. 57).

Planned Change Theory

Organization change results from action by organization leaders, with participation and collaboration by organization members, to

- Plan for addressing significant opportunities, problems, issues, and concerns,

- Envision and set shared organization goals,

- Manage the transition to implementation of those goals, and

- Evaluate the outcome.

Outcomes are new structures and organizing processes (Kezar, 2001, p. 57, Van de Ven, 2011, p. 60).

Developmental and Stage-Based Change Theory

Change occurs as a progressive sequence of phases and natural, logical, or institutional activities and requirements over time. For example, organizations are born, experience rapid growth and efficiency, mature and experience diseconomies of scale and crisis, and transform or decline. Outcome is a new organizational identity (Kezar, 2001, p. 57; Van de Ven, 2011, p. 60).

Conflictive and Power-Based Change Theory

Change results from tension and conflict created when people of the dominant (power) culture create organizational processes and structures that preserve the status quo, maintain their privilege and interests, and prevent equitable treatment for members of subordinated cultures. Change results when members of subordinated cultures gain sufficient power to confront and engage the dominant culture on issues through agenda setting, networking, coalition-based action, bargaining, and negotiation. Outcomes are new processes, new structures and new cultures (Kezar, 2001, p. 57; Van de Ven, 2011, p. 60).

Narrative-Based Change Theory

Members of organizations interpret their world and construct and reconstruct reality on an ongoing basis. Change occurs when the narratives/stories/conversations of organization members describing organization reality changes in a substantive way, which impacts organization decisions, actions, and behaviors and, in turn, organization culture. Leaders address organization opportunities, issues, problems, and concerns by changing current conversations, metaphors, and stories. This shapes organization reality and behavior “by involving more and different voices, altering how and which people engage with each other, and/or by stimulating alternative or generative images that shape how people think about things” (Marshak & Bushe, 2013, pp. 1–2). Change is a process of social construction of a new organization reality, resulting in new decisions, actions, and behaviors, and culture (Bushe, 2013).

These five organization change theories, and other organization change theories not described here, form a foundation for organization change models that are blueprints to guide organization change initiatives. A series of organization change models are described in the next section.

Organization Change Models

There are many organization change models—possibly hundreds. A Google search for “organization change models” yields 51,500,000 results. Examples of organization change models are listed in Exhibit 13.1 and described in this section.

Open System Model

Many organization change models incorporate the open system model of organizations developed by Karl Ludwig von Bertalanffy (1969). An organization that is an open system must constantly interact with its external environment to survive and grow. The organization imports inputs from the external environment and exports products and services to meet the needs of customers. Inputs include financial, human, and material resources, equipment, technology, information, and energy. The external environment may value some outputs, products, and services and other outputs seen as having negative and adverse effects e.g. discrimination, employee layoffs, and pollution. The organization includes internal processes, structures, and subsystems that convert inputs to outputs. The open system model is illustrated in Figure 13.1.

FIGURE 13.1. OPEN SYSTEM MODEL

The external environment is composed of individuals, organizations, communities, nations, and the earth, and includes customers, suppliers, distributors, government agencies, competitors, and partners. The organization’s external environment also includes culture and cultural values, economic conditions, the legal, regulatory, and political environment, the quality and availability of education and health services, and the quality and availability of earth resources, such as water, soil, and trees.

Feedback between the organization and its external environment is needed for evaluation learning and change. The organization receives feedback about the value of its outputs, the availability of needed inputs, achievement of the financial and non-financial goals and objectives, and other ways the organization is perceived by the environment. The organization sends feedback to entities in its environment through its outputs, public relations, advertising, promotions, its use of inputs, and both the positive and adverse impacts it has on entities in its environment.

The organization has boundaries that differentiate it from entities in its environment. The organization’s boundaries must be permeable to the external environment for the organization to survive, grow, and be healthy. When organization boundaries are too permeable, the forces, pressures, and demands of the external environment can be overwhelming, negative, and destructive. When boundaries have too little permeability, the organization can be cut off from opportunities, information, and the resources it needs from its environment to survive and grow.

The organization depends on the openness of interactions at its boundaries with entities in its external environment for the change, development, and learning it needs to survive, grow, and be healthy. The organization must also defend against and resist threats, forces, and adverse pressures exerted on the organization at its boundaries with the external environment. Both change and resistance show up at the organization’s boundaries with its environment. The capacity for change and resistance are necessary for the health and survival of the organization.

Models of Change, Status Quo, and Resistance

Change and resistance are needed for the health and survival of organizations in the open-system model. Organization change models that feature stability, resistance and change are explored in this section. They include Kurt Lewin’s force field model and the Gestalt resistance and change model.

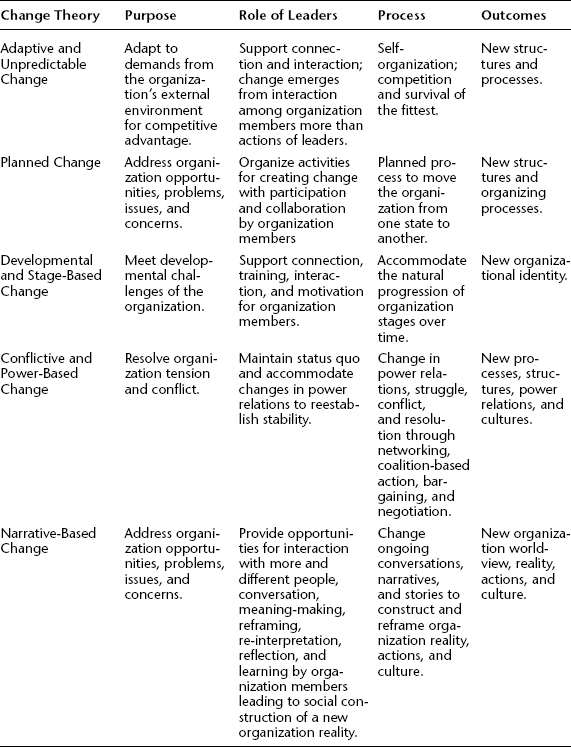

Force Field Change Model

The force field change model was one of three organization change models created in the 1940s by Kurt Lewin. The other two models, the unfreeze-change-refreeze and action research models, are explored later in this chapter. The force field model describes the current reality of an organization as the outcome of driving forces that encourage change and restraining forces that discourage change. A key assumption of the model is that forces for change and forces for status quo are ever present. They both need to be considered to understand the organization’s current situation, to initiate organization change, and to adapt to unforeseen change. A change in the organization’s current reality can be initiated by the organization by strengthening the driving forces for change and weakening the restraining forces for maintaining the status quo. In order for change to occur the driving forces must exceed the restraining forces.

Driving and resisting forces are a mix of people, habits, customs, processes, structures, beliefs, and attitudes. Lewin’s force field change model involves exploring the current situation in terms of the balance between forces for change and forces for status quo, determining the key players and circumstances, defining the desired change, and developing strategies for change that heighten driving forces for change and lessen restraining forces for maintaining the status quo (see Figure 13.2).

FIGURE 13.2. FORCE FIELD CHANGE MODEL

Gestalt Resistance and Change Model

The force field change model examines the relationship between resistance and change and incorporates the assumption that forces for status quo and forces for change are always present. The Gestalt Institute of Cleveland has developed an expanded understanding of the phenomena of change and resistance and the forces for change and status quo in its resistance and change model (Nevis, 1987; Wheeler, 1991). From a Gestalt perspective:

- Resistance is a defense against forces for change in order to maintain the organization’s boundaries, integrity, and well-being.

- Resistance accompanies change and is a normal, useful, and necessary phenomena of organizations, a process to be respected rather than seen as alien and needing to be destroyed (Nevis, 1987, pp. 143–144).

- Resistance is a container for energy . . . energy used for the organization’s health and survival. Resistance maintains the organization’s integrity by partially or totally blocking energy, information, feedback, and goods and services from its external environment.

- Resistance manifests where individuals and organizations are at a power disadvantage (Nevis 1987, p. 144).

- Resistance to entities in the organization’s environment has a corresponding form of contact with entities in the organization’s environment. Contact involves engaging partially or fully with the energy, information, perspectives, and material, goods, and services from entities in its environment and the change that can result for the organization.

- Organizations may prefer and use one of the forms of resistance and contact more than others, though they use the others as well.

The traditional list of six resistances from the Gestalt Institute of Cleveland includes desensitization, confluence, introjection, projection, retroflection, and deflection, although many other forms of resistance could be included. There are corresponding forms of contact. These six forms of resistance and contact are described in Exhibit 13.2.

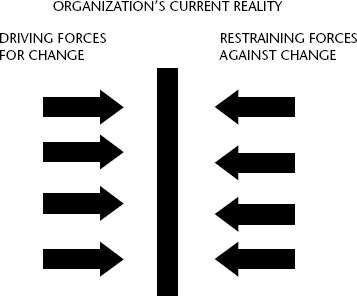

Multicultural Organization Development Change Model

Diversity, inclusion, and social justice are seldom considered in organization change models (Brazzel, 2008). The one exception is the model created by Bailey Jackson and Rita Hardiman in the 1980s that has come to be known as the multicultural organization development model (Jackson, 2006; Jackson & Hardiman, 1981, 1994). This is an early-phase, middle-phase and later-phase developmental and stage-based model in which change occurs in a progressive sequence of phases and stages as organizations develop and change their understanding of and approach to addressing diversity, inclusion, and social justice. This pioneering work of Jackson and Hardiman has been elaborated on in later work of Jackson and Holvino (1986, 1988), Miller and Katz (1995), and Brazzel (2007).

Organization tension and conflict result when people of the dominant (power) culture create organizational processes and structures that preserve the status quo, maintain their privilege and interests, and prevent equitable treatment for members of subordinated cultures. Change occurs when members of subordinated cultures gain sufficient power to confront and engage the dominant culture and call for equitable treatment and new cultural processes and structures.

A version of the model is described by Brazzel (2007) in which there are three organizational phases: the dominant-culture organization, the pluralistic, dominant-culture organization, and the integrating-culture organization. (See Figure 13.3.) The model can be used to diagnose the current position of an organization, organizational units, or groups of people in an organization’s development from a dominant-culture to integrating-culture organization and to suggest intervention strategies that are appropriate for current phases of the organization. Organization diversity strategies and initiatives, which can help the organization move from one phase to another, are different for each of the organizational phases.

FIGURE 13.3. DEVELOPMENTAL PATTERNS AND IMPACTS OF DIVERSITY, INCLUSION, AND SOCIAL JUSTICE IN ORGANIZATIONS

Source: Brazzel, 2007.

Lewin Change Models

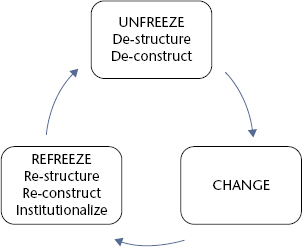

Unfreeze-Change-Refreeze Model

Lewin’s unfreeze-change-refreeze model is a cornerstone model for understanding the organization change process that provides a three-step picture of how organizations change: unfreezing the organization, implementing the change, and refreezing the organization (Lewin, 1951). See Figure 13.4. The first step of unfreezing involves convincing those affected by the change that the change is necessary; the second is making the change; and the third is making the change a permanent way of doing business.

FIGURE 13.4. LEWIN UNFREEZE-CHANGE-REFREEZE MODEL

Unfreezing

This step is about helping the organization get ready and motivated to change, understand that change is necessary, and prepare to move into action and away from the more comfortable, current situation. This involves destabilizing the current situation by developing a compelling message and sense of urgency about why the existing way of doing things cannot continue; reexamining and challenging the core beliefs, values, attitudes, and behaviors of the current situation; creating a critical mass of support for the change; and developing and communicating a change vision and strategy.

Change

In the second step, desired changes are implemented and the organization begins moving toward the desired outcome. Change is a process and not an event–a process of developing new thoughts, feelings, and behaviors to help move the organization, learning about the changes, and understanding how the changes will be beneficial. Time and communication are important for the changes to occur. People need time to understand the changes and they need support, training, coaching, role models, acceptance that mistakes as part of the learning process, and clear and on-going communication about the desired change and its benefits for the organization. As people begin to resolve their uncertainty and look for new ways to do things, they begin to believe and act in ways that support the new direction.

Refreezing

Refreezing is creating and reconstructing stability once a change has been implemented, establishing the change as the “new normal,” and anchoring and institutionalizing it in the fabric of the organization . . . reinforcing and locking it in so that people in the organization feel confident and comfortable with the new beliefs, values, attitudes, behaviors, and ways of working and do not go back to doing what they were used to doing.

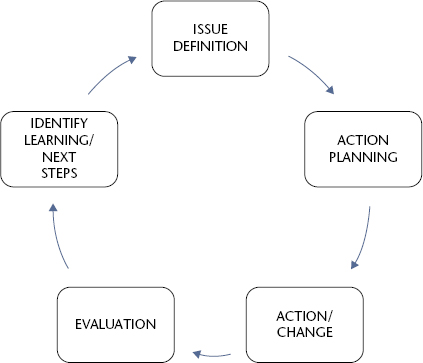

Action Research Change Model

Kurt Lewin created the term “action research” in his paper “Action Research and Minority Problems” (Lewin, 1948). Lewin used action research to address issues involving inter-social-identity-group relations, problems of discrimination, and social action and change.

He described action research as “research on the conditions and effects of various forms of social action and research leading to social action” using a process of “a spiral of steps each of which is composed of a circle of planning, action, and fact-finding about the result of the action” (Lewin, 1948, pp. 144–146).

Lewin further defined “fact-finding” to include evaluating what the action has achieved, identifying learning and possible next steps, and providing information for “modifying the ‘overall plan’” (Lewin, 1948, p. 146).

The action research change model is shown in Figure 13.5. It includes issue-definition, action planning, action/change, evaluation of the results of the action, learning and next steps, and then moving to the next cycle of steps and action.

FIGURE 13.5. LEWIN’S ACTION RESEARCH CHANGE MODEL

Action research has become a core research and organization change methodology for the field of organization development. In action research, there is a commitment to study and change the organization in collaboration with members of the organization and participants in the change process. The action researcher in this process is a co-learner with participants in the research. Action research has four important elements:

- Learning—learning by doing and learning through action;

- Organization change;

- Participation—empowerment of participants; research with, rather than research about, on, or for; and

- Collaboration between researcher and participants at every step.

Dialogic and Diagnostic OD Change Models

Gervase Bushe and Robert Marshak began a conversation about the emergence of the dialogic OD change model around 2005–2006. In order to continue and encourage further understanding of dialogic OD, they edited a special edition of the OD Practitioner in 2013, “Advances in Dialogic OD” (Bushe & Marshak, 2013). In this special issue, Marshak and Bushe contrasted dialogic OD with diagnostic or foundational OD change models and noted that the OD field is now divided into two forms of OD—dialogic OD and diagnostic OD (Marshak & Bushe, 2013, p. 1). Marshak asks that dialogic and diagnostic OD be considered in a both/and rather than in an either/or way and foresees them being used together and separately to change organizations (Marshak, 2013). The dialogic OD model is clearly seen now as a separate form of OD. The conversation about the dialogic OD change model is recent. The understanding of dialogic OD and whether there are only two forms of OD is still emerging. A brief discussion of the dialogic and diagnostic change models follows.

Dialogic OD Change Model

Marshak and Bushe write that “Dialogic OD is based, in part, on a view of organizations as dialogic systems where individual, group, and organizational actions result from socially constructed realities created and sustained by the prevailing narratives, stories, metaphors, and conversations through which people make meaning about their experiences. From this perspective change results from changing the conversations that shape everyday thinking and behavior by involving more and different voices, altering how and which people engage with each other, and/or by stimulating alternative or generative images to shape how people think about things” (2013, pp. 1–2).

In the dialogic OD change model, change is a process of social construction of a new organization reality, resulting in new decisions, actions, behaviors, and culture (Bushe, 2013). Organization leaders (and diagnostic OD practitioners) provide structures and containers for discussion and conversation and serve as host for what happens in the conversations among participants using appreciative inquiry, future search, world café, open space, and other technologies that support new dialogue, conversations, narratives, stories, and images. By using the dialogic OD change process, organization leaders provide opportunities for conversation and the development of new and changed organization realties. They are not attempting to generate specific, targeted changes and results.

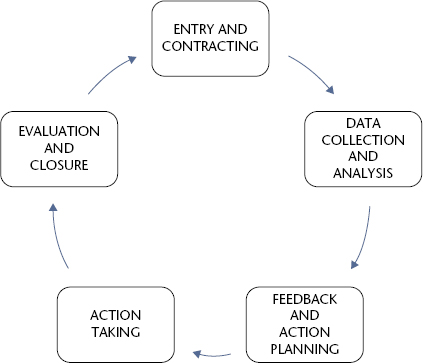

Diagnostic OD Change Model

Marshak and Bushe describe the change process for the diagnostic OD change model as “change driven by diagnosing how to objectively align or realign organizational elements (strategies, structures, systems, people practices, etc.) with the demands of a broader environment as suggested by open systems theory” (2013, p. 2). They include the Lewin unfreezing-change-refreezing and action research models as examples of diagnostic OD, as well as the “phases of the OD consulting process” change model (Marshak, 2013, p. 54). The phases of the OD consulting process change model is based in action research and the unfreezing-change-refreezing model and usually includes entry, contracting, data collection and analysis, feedback and action planning, action-taking, and evaluation and closure phases (see, for example, Tschudy, 2006, pp. 167–171). (See Figure 13.6.)

FIGURE 13.6. PHASES OF THE OD CONSULTING PROCESS CHANGE MODEL

As a change model, the phases of the OD process support a shared and participatory organization change process. The contracting and entry phase provides the basis for a solid, trusting relationship between the organization and the OD practitioner and a shared agreement about the change process. The data collection, analysis, feedback, and action planning processes raise awareness and a sense of the urgency for change. They mobilize energy for the change that is implemented in the action-taking phase. The results of the change, learning, next steps, and completion are established in the evaluation and closure phase.

Models of Organization Change and the Organization’s Current Reality, Transition, and Desired Future

Building on Lewin’s unfreezing-change-refreezing model, there are a rich variety of organization change models that visualize the change process as including the current organizational reality, a transition process, and the desired organizational future. Examples of organization change models that fit this current reality, transition, and desired future framework are described in this section of the chapter. They include the Beckhard-Harris present-state, transition-state, future-state change model (1977), Fritz creative-tension change model (1984, 1996), paradoxical theory of change (1970), and strategic planning change model (Bryson, 1988). These models give relatively little consideration to the deep emotions that can result from organization change and the impact they can have on the organization change process. Aspects of the Bridges transitions model (1988), Tannenbaum-Hanna’s holding-on, letting-go, and moving-on model (1985), Kubler-Ross’s death and dying model (1996) are also mentioned in this section to include consideration of the role of emotions in the organization change process.

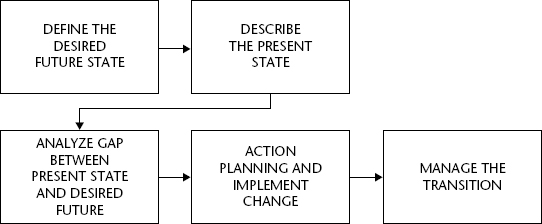

Present-State, Transition-State, Future-State Change Model

Richard Beckhard and Reuben Harris (1977) created the well-known, present state, transition state, future state organization change model. Their model includes the following steps:

- Define the desired future state

- Describe the present state, the current situation for the organization

- Gap analysis: assess the current situation in relation to the desired future

- Action planning: determine and implement changes needed to accomplish the vision for the organization’s future state

- Manage the transition from the organization’s current reality to its desired future

In the Beckhard-Harris organization change model, change is driven by the organization’s vision of their desired future state (see Figure 13.7).

FIGURE 13.7. PRESENT STATE, TRANSITION STATE, FUTURE STATE CHANGE MODEL

Source: Adapted from Beckhard and Harris, 1977.

Following are descriptions of the present state, transition state, and future state in the Beckhard and Harris’ change model:

Present State

The current state is the current reality of the organization—the organization’s daily work and the processes, structure, and people who are involved. The present state is comfortable, known, and a time when roles and responsibilities are understood by members of the organization. It is the foundation and context for planning for organization change, the first stage in the change process, the time when a change management strategy is developed and change begins to be talked about in the organization. Here, the organization defines its vision for the desired future of the organization, determines the organization’s current situation and the forces for and against change, and asks “Why change?” The organization analyzes the gap between the organization’s current situation and its desired future and defines and plans the actions needed to move from the present state to the future state.

William Bridges refers to this initial stage in the change process as the endings stage (1980, 1988). Robert Tannenbaum and Robert Hanna describe it as a time of “holding on” (1985). It can be a stage where organization members, and the organization as a whole, experience strong emotion, resistance, and loss—loss now and the potential of future loss—loss of security, safety, comfort, competency, relationships, belonging, direction and purpose, territory, physical space, roles, and responsibilities. Emotions at this time include grief, fear, denial, anger, sadness, disorientation, helplessness, alienation, frustration, betrayal, uncertainty, shock, and mourning. The endings and loss from organization change can be experienced as “little death” and have all the characteristics of Kubler-Ross’ stages of death and dying—denial and isolation, anger, rage, resentment, envy, bargaining, depression, mourning, and, finally, acceptance (1996). The reality that something is ending and the emotions that members of the organization are experiencing have to be acknowledged before they can begin to accept the reality of new directions for the organization.

Transition State

The transition state is the second stage in the organization change process in which the organization’s change agenda is implemented and managed. The organization, people, processes, and structures are in transition—moving from the organization’s present state to its desired future. The old signposts about how to be and what to do to be successful are gone and new signposts have not replaced them.

Bridges (1980, 1988) calls this stage “the neutral zone.” It is an eerie, uncharted, muddled, and foggy land between what used to be and what has not yet happened. Very little is clear. Organization members are drawn to the organization as it was and still trying to figure out the new organization. Tannenbaum-Hanna (1985) see it as a time when members of the organization are beginning to let go of the past and are uncertain about what the future will bring. It can be a time of feeling lost, low morale and low productivity, uncertainty, confusion, ambiguity, being without direction, anxiety about roles, status, and identity, much stress, and skepticism and resentment about the change agenda. This can also be a time when members of the organization begin trying on new ideas and ways of working. It can also be a time of creativity, innovation, and renewal.

Future State

The future state is the last stage of the change process. It is how things will be after the change agenda is fully implemented. Bridges (1980, 1988) calls it the new beginning, a time of rebirth and renewal. At this stage, members of the organization may experience hopefulness, acceptance, high energy, openness to learning, joy, enthusiasm, vitality, meaningfulness, engagement, clarity, and renewed sense of identity and commitment to the organization and their roles. People have begun to embrace the changes that are being introduced in the organization and to understand new roles, ways of working, and responsibilities. They are developing the new skills they need to be successful and starting to see early successes from their efforts.

Creative Tension Organization Change Model

The creative tension model created by Robert Fritz is a decision-making structure that produces structural tension for organizational creativity and change (1984, 1999). Creative tension is formed in a three-step process shown in Figure 13.8:

FIGURE 13.8. CREATIVE TENSION ORGANIZATION CHANGE MODEL

Source: Adapted from Fritz, 1984, 1999.

- Define the organization’s vision as clearly and in as much detail as possible. A vision is what the organization wants (not what the organization does not want, which is more about current and past problems and issues).

- Define the organization’s current reality. The current reality is a statement of “what is.”

- While holding both vision and reality, notice what action steps come to mind for moving toward what the organization wants, and do those.

The gap between vision and reality creates an emotional, energetic, and cognitive tension that seeks to be resolved by marshaling creativity, energy, and resources into designing and taking action on steps to resolve the tension. Creative tension is a structure that facilitates creativity and change. The greater the gap between vision and reality, the greater the tension, and the stronger the motivation and energy in the organization to resolve that tension.

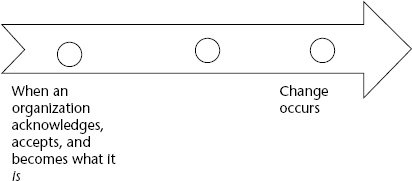

Paradoxical Theory of Change

The paradoxical theory of change is a core part of the Gestalt theory of organization change. Arnold Beisser describes the paradoxical theory of change as “change occurs when one becomes what he is, not when he tries to become what he is not” (1970, p. 77). Beisser applies the paradoxical theory of change to individual change. Later, he adds: “it is proposed that the same principles are relevant to social change, that the individual change process is but a microcosm of the social change process” (p. 77). The paradoxical theory of change applies to individuals, groups, organizations as well as society (Maurer, 2003). From the perspective of organization change, the paradoxical theory of change can be written as: when an organization acknowledges, accepts, and becomes what it is, change occurs. (See Figure 13.9.)

FIGURE 13.9. PARADOXICAL THEORY OF CHANGE

Source: Adapted from Beisser, 1970.

The paradoxical theory of organization change suggests:

- The work of organization change is heightened awareness of “what is” and of current organization experience, not the need and urgency of change.

- An organization cannot change until it accepts and becomes what it is.

- The harder an organization tries to change and be different than it is now, the more likely it will stay where and what it is now.

- The role of the leader (and OD practitioner) is to be an agent of current experience and “what is” and not an agent of change. Being an agent of “what is” is the best way to be an agent of change.

- What is needed for an organization to change, not how change happens.

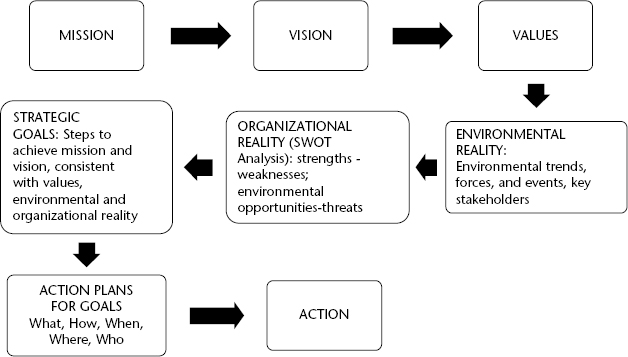

Strategic Planning Organization Change Model

The strategic planning organization change model is a structured, participative approach for key decision-makers in an organization to engage in fundamental decisions and actions that shape what an organization is, what it does, and why it does it (Bryson, 1988, p. 3). It is a model of strategic thinking and acting that considers mission, vision, values, the current organizational and environmental realities, and the actions needed to achieve the mission and vision, consistent with the values, and organizational and environmental reality. (See Figure 13.10.) The planning process answers three key questions in the context of the organization’s mission, vision, and values:

FIGURE 13.10. STRATEGIC PLANNING CHANGE MODEL

Source: Adapted from Bryson, 1988.

- How are things now in the organization and in its environment?

- What is the organization’s desired future?

- What steps does the organization need to take to move from where it is now to its desired future?

The purpose of the strategic planning organization change model is action.

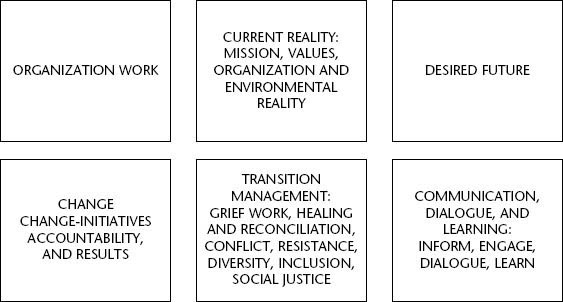

Organization Work and Five Tasks of Managing Change

Change initiatives are difficult, complex, and subject to failure. When change initiatives are seen as competing with and isolated from the core work and tasks of the organization, they are even less likely to be successful. Today organization change is an integral part of the work of the organization (Fishman, 1997, p. 64). The organization’s management processes include the management both of change initiatives and of the organization’s core work. They are interrelated.

A rich variety of organization change models have been discussed in this chapter. There are many other organization change models that have not been covered here. The number and variety of organization change models can lead to confusion, competing claims about which is “best,” and jokes about the latest “fad of the month.” In fact many of the models are complementary and overlapping and address key aspects of the organization change process.

The change models described in this chapter are integrated as complementary parts of the change management process, connected with the work of the organization, and shown as the “multi-task organization work and change management model” in Figure 13.11. The multi-task model includes work and change management processes as the core work of the organization. The six tasks of organization work and change management responsibility and processes are addressed simultaneously. Change management activities are described in five of the tasks: current reality, desired future, change, transition management, and communication, dialogue, and learning.

FIGURE 13.11. MULTI-TASK ORGANIZATION WORK AND CHANGE MANAGEMENT MODEL

Source: Brazzel, 2013.

Change is ongoing and the work and change management tasks are interdependent and ongoing, as well. The activities in each task incorporate a learning-by-doing perspective and represent interventions that can change the organization. Knowledge and information gained in one task inform and impact the management processes of other tasks. Activities (that is, change initiatives) in the five change management tasks inform the management of core organizational work. When change initiatives are segregated from the management of organizational work, organizations can miss important forces, data, learning, and opportunities for improvement.

Conclusion

A range of organization change theories and models are described in this chapter. In the process of describing these organization change theories and models, several aspects of the available theories and models stand out:

- Organization development and change practitioners have a rich and varied catalog of organization change theories and models to help organizations understand, explain, and predict organization change and guide organization change initiatives and organization responses to change.

- Organization change is featured in current theories and models. Less attention is given to the importance and role of resistance. A companion chapter on resistance theories and models would have much less depth and variety.

- Change initiatives can be used to preserve the status quo and maintain the privilege and interests of people of the dominant (power) culture in organizations and prevent equitable treatment for members of subordinated cultures.

- Changes in power relations through conflict, struggle, and resistance are seldom considered in available change theories and models. Consideration of intergroup relations and dynamics, use of power, diversity, inclusion, social justice, oppression, and conflict are mostly missing in current models.

- Primarily white men from Western nations have developed the organization change theories and models discussed in this chapter. Change theories and models that consider equality, oppression, inclusion, and diversity have been developed by men and women of color and seldom by white people. This may reflect both the culture, race, and gender short-sidedness of the author and limited and narrow perspectives of available theories and models.

- Deep emotions of fear, anger, betrayal, grief, denial, sadness, disorientation, helplessness, and alienation are an expected, normal, and impactful part of the organization change process. Many models do not consider the impact of emotion and treat it as a peripheral part of the change process. This can have the effect of driving emotion underground where it becomes a covert part of the change process.

- The recent conversation about the dialogic OD change model is giving valuable attention to the role and importance of dialogue, conversation, and narrative for organization change initiatives and the extent to which these processes are already being used by organization development and change practitioners.

This list of the rich bounty and flat sides of current organization change theories and models offers wonderful opportunity for research and expanded development of theories and models by organization development and change practitioners and scholars.

References

Beckhard, R., & Harris, R. T. (1977). Organizational transitions: Managing complex change. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

Beisser, A. R. (1970). The paradoxical theory of change. In J. Fagan & I. L. Shepard (Eds.), Gestalt theory now: Theory, techniques, application (pp. 77–80). Palo Alto, CA: Science and Behavior Books.

Brazzel, M. (2007, December). Developmental patterns of diversity, inclusion, and social justice in organizations. Available from http://michaelbrazzel.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/09/Developmental-Patterns-of-diversity-inclusion-and-social-justice-in-organizations-8–10–12.pdf.

Brazzel, M. (2008, Spring). Deep diversity, social justice, and organization development. OD Seasonings: A Journal by Senior OD Practitioners, 3(3). Available from http://michaelbrazzel.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/07/BrazzelODSeasoningsDeepDivSJODSummer2008.pdf.

Brazzel, M. (2013, March). Organization work and change management: A multi-task model. Available from http://michaelbrazzel.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/Organization-Work-and-Change-Management.pdf.

Bridges, W. (1988). Surviving corporate transition. New York: Doubleday.

Bryson, J. M. (1988). Strategic planning for public and nonprofit organizations: A guide to strengthening and sustaining organizational achievement. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Bushe, G. R. (2013, Winter). Dialogic OD: A theory of practice. OD Practitioner, Special Issue: Advances in Dialogic OD, 45(1), 11–17.

Bushe, G. R., & Marshak, R. J. (Eds.). (2012, Winter). OD Practitioner, Special Issue: Advances in Dialogic OD, 45(1), 1–66.

Fishman, C. (1997, April/May). Change. Fast Company. www.fastcompany.com/28199/change

Fritz, R. (1984). The path of least resistance: Principles for creating what you want. Salem, MA: Stillpoint.

Fritz, R. (1996). Corporate tides: The inescapable laws of organizational structure. San Francisco, CA: Berrett-Koehler.

Jackson, B. W. (2006). Theory and practice of multicultural organization development. In B. B. Jones & M. Brazzel (Eds.), The NTL handbook of organization development and change: Principles, practices, and perspectives. San Francisco, CA: Pfeiffer, pp. 139–154.

Jackson, B. W., & Hardiman, R. (1981). Organizational stages of multicultural awareness. (unpublished paper).

Jackson, B. W., & Hardiman, R. (1994). Multicultural organizational development. In E. Y. Cross, J. H. Katz, F. A. Miller, & E. W. Seashore (Eds.), The promise of diversity: Over 40 voices discuss strategies for eliminating discrimination in organizations. New York: NTL Institute/Irwin, pp. 231–239.

Jackson, B. W., & Holvino, E. (1986). Working with multicultural organizations: Matching theory and practice. In R. Donleavy (Ed.), OD Network 1986 conference proceedings, pp. 84–96.

Jackson, B. W., & Holvino, E. (1988, Fall). Developing multicultural organizations. Journal of Religion and the Applied Behavioral Sciences, pp. 14–19.

Kezar, A. (2001). Understanding and facilitating organizational change in higher education in the 21st century. ASHE-ERIC Higher Education Report, 28(4).

Kubler-Ross, E. (1996). On death and dying. New York: Macmillan.

Lewin, K. (1948). Action research and minority problems. In G. W. Lewin (Ed.), Resolving social conflicts: Selected papers on group dynamics (pp. 143–152). New York: Harper & Row.

Lewin, K. (1951). Field theory in social science. New York: HarperCollins.

Lewin, K. (1958). Group decision and social change. In E. E. Maccoby, T. M. Newcomb, & E. I. Hartley (Eds.), Readings in social psychology (pp. 197–211). New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

Marshak, R. J. (2013, Winter). The controversy over diagnosis in contemporary organization development. OD Practitioner, 45(1), 1–4.

Marshak, R. J., & Bushe, G. R. (2013, Winter). An introduction to advances in dialogic organization development. OD Practitioner, 45(1), 54–59.

Maurer, R. (2003). Using the paradoxical theory of change in organizations. The Gestalt Review, 7(3). www.gestaltcleveland.org/pdf/paradoxical.pdf

Miller, F. A., & Katz, J. H. (1995). Cultural diversity as a developmental process: The path from a monocultural club to inclusive organization. In J. W. Pfeiffer (Ed.), The 1995 annual, volume 2: Consulting. San Francisco, CA: Pfeiffer.

Nevis, E. C. (1987). Organizational consulting: A Gestalt approach. New York: Gardner Press.

Tannenbaum, R., & Hanna, R. W. (1985). Holding on, letting go, and moving on: Understanding a neglected perspective on change. In R. Tannenbaum, N. Margulies, F. Masserik, and Associates (Eds.), Human systems development: New perspectives on people and organizations (pp. 95–121). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Tschudy, T. (2006). An OD map: The essence of organization development. In B. B. Jones & M. Brazzel (Eds.), The NTL handbook of organization development and change: Principles, practices, and perspectives (pp. 157–176). San Francisco, CA: Pfeiffer.

Van de Ven, A. H., & Sun, K. (2011, August). Breakdowns in implementing models of organization change. Academy of Management Perspectives, pp. 58–74.

von Bertalanffy, K. L. (1969). General system theory: Foundations, development, applications (rev. ed.). New York: George Braziller.

Wheeler, G. (1991). Gestalt reconsidered: A new approach to contact and resistance. Cambridge, MA: GIC Press.