CHAPTER THREE

VALUES, ETHICS, AND OD PRACTICE

David Jamieson and William Gellermann

The values of organization development (OD) practitioners affect both what they do and how they do it. Their values can either align with or clash with the values of client organizations.

This chapter examines the importance of values for OD practitioners: in their work with human systems, in the means and the ends of change, in the philosophy and methods of OD, and in establishing ethical standards for practice. The historical roots and evolution of OD values are discussed, as well as their erosion and subsequent renewal. The chapter closes with a current view of the value base of OD and its differentiation from many other approaches to change.

Throughout this chapter, “values” are conceived as “standards of importance,” such as integrity, honesty, effectiveness, efficiency, productivity, profitability, service and quality of life, while “ethics” are defined as “standards of good and bad behavior based on values.” “Organization development” refers to a values-based process of improving individuals, relationships, and alignment among organizational components to enhance the effectiveness of the organization and the quality of life for its members to better serve the organization’s purpose and their fit with the larger system of which the organization is itself a subsystem. And “OD practice” refers to the concepts, strategies, and methods used in facilitating the OD process.

Values and OD Practice

Values are fundamental to OD practice because values determine the degree to which OD practitioners are aligned with the purpose and values of client organizations and how they work with clients. Practitioner values shape individual purpose and meaning, personal conduct, and means of working with clients. People’s value bases guide them toward wealth or service, power or helping, achievement or contribution, personal gain or social responsibility. Individual values shape personal conduct in such areas as integrity, authenticity, honesty, compassion, trustworthiness, roles and boundaries, human dignity, and personal growth. Finally, practitioner values are embedded in the means used to work with systems affecting such things as collaboration, community, inclusion, learning, participation, empowerment, equality, justice, choice, responsibility, differences, and spirituality.

Client systems also operate with value bases. Organizations’ values are related to their outcomes (what they accomplish), conduct, and ways of working (their culture). When the client’s values differ significantly from a practitioner’s values, the decision to work together comes into question, and if they are working together, serious problems with motivation, commitment, and integrity are likely; and conflict is inevitable.

Awareness of practitioner and client values is an important first step, but the reality is more complex. There can be multiple values, with different priorities, at different times, under different conditions. There can also be a lack of clarity among actual values, espoused values and desired values which highlights the importance of being clear about which values are operating (Hultman & Gellermann, 2001).

Values Conflicts and Dilemmas

Values can come into conflict, and conflicting values, within practitioners or between practitioners and clients, lead to dilemmas about what to do. Sometimes a value is so central and strong that the choice between values is clear and unambiguous, and there is no dilemma. More often shades of gray pervade and the challenge is to balance priorities (either personal or combined with others’) while the “self” (who we are) is operating to help or hinder thoughts, choices, and actions.

Now consider some examples of situations involving value conflicts and ethical dilemmas at the core of an OD practitioner’s worldview and practice: How would you respond? Which of your values and which of your ethics would guide your actions?

- You are an independent consultant. You have not been selected for the last few projects for which you submitted proposals. Now there is the possibility of work for which you do not have the requested background. You are sure you can do the work and you know you would never be selected if you say you do not have that background.

How would you respond? Which of your values and which of your ethics would guide your actions?

- You are feeling in a bind. You have uncovered some information that would help your primary client, but if you use it, you will have to violate your promises of confidentiality to others in your client system,

How would you respond? Which of your values and which of your ethics would guide your actions?

- You are working with a poor community in a different culture on a grant for an international financial institution. You know OD and how to help a client improve processes at all levels, become more effective, and develop potential. However, openness and authenticity are not valued in this culture and self-sufficiency has become a way of life. It is clear to you that the people in this community need to be able to air differences and learn to work together. You feel caught between respecting existing values and intervening to create new behaviors. You have built good relations with your key clients in the community and are responsible to the institution for results.

How would you respond? Which of your values and which of your ethics would guide your actions?

These and other scenarios are commonplace and demonstrate the many different ways that values, values dilemmas, and ethics can impact the practice of OD.

Values as Guides

Some argue that values are “shoulds” that must be universally adhered to. However, this chapter takes the perspective that values are “standards” that practitioners are each responsible for considering based on their own experiences, choices, and reflection.

Values can be thought of as guides—developed over a lifetime of influences, experiences, and reflection. Core values serve as a rudder to steer through varied situations. Values can be adapted and changed over time, based on reflection about life’s influences and experiences. Some values are more deeply held and more a part of one’s core identity, while others are relatively less important, less central, and less fundamental.

The relativity of values shows up in corporations when the greed of a few wins over the satisfaction of many; when CEOs and others increase their own wealth while stockholders lose money and employees are laid off. For example, the ratio of CEO annual compensation to that of the typical worker by 2010 was 243 to 1 (Stiglitz, 2012). It shows up when individuals value justice, but often feel unfairly treated. Or when practitioners believe in equality with the client, yet put up with being treated like a “hired hand.”

Understanding one’s own value hierarchy helps practitioners make decisions, resolve dilemmas, compromise, and stand firm. Values are guides about what to pursue or prefer. Values impact what practitioners want from life (as reflected in purpose or desired outcomes) and how to live life and engage with others (conduct, means). Yet, the reality of the world, circumstances of the moment, and the “self”—who one is—can interfere with, modify or even change the way practitioners live their values.

Values and “Self”

The “self”—who one is and one’s core identity—plays an important role in the work of OD practitioners in terms of their use of self as instruments of change. Values are part of the OD practitioner’s self and values interact with other parts of the “self” in their expression. This interaction can support and strengthen a value, hinder and weaken its expression, or even change the importance the practitioner gives to it (Jamieson, 2003; Jamieson, Auron, & Shechtman, 2010). For example, a practitioner may truly value openness and be able to live that value with most people. But then, with some people, the practitioner may have an overriding fear of losing the person’s affection or approval and thus the interaction becomes less direct and open. Or consider the OD practitioner who has a hard time confronting authority figures and keeps compromising values when “highers-up” push for outcomes or methods that reflect different values.

From another perspective, in a prior study several practitioners were interviewed about “downsizing” in the organizations where they worked. Generally, these practitioners had a tendency to resist downsizing when it was done in response to short-term drops in demand, although most went along with it reluctantly. In two cases, practitioners had values so strong that they protested. They were unsuccessful and resigned because they believed that downsizing would be harmful to the organization by destroying the trust, loyalty, and motivation of workers. Practitioners’ responses to higher management seeking to downsize employees are an example of how practitioner values can conflict with the values of the organizations that employ them.

OD Values: Then and Now

Values have always been central to the development and practice of OD. They brought the founding practitioners together and provided focus and identity to early OD work. Values have continued, with varied strength and emphasis, to differentiate OD practice from many other approaches to change, management, consultation, and facilitation.

The early values of OD were central to its identity as a profession because these values were so different from prevailing values in operation in organizations. Prior to the early days of organization development, organizations operated on principles of mechanistic and bureaucratic systems, including authority obedience, division of labor, hierarchical supervision, formalized procedures and rules, chain of command, top-down directives, and impersonality. In contrast, the field of OD brought distinctly different values that were a counter-force to the prevailing organizational environment. OD offered a more holistic view of people and organizations and the belief that this different approach was not only better for people, but also for the performance of the organization.

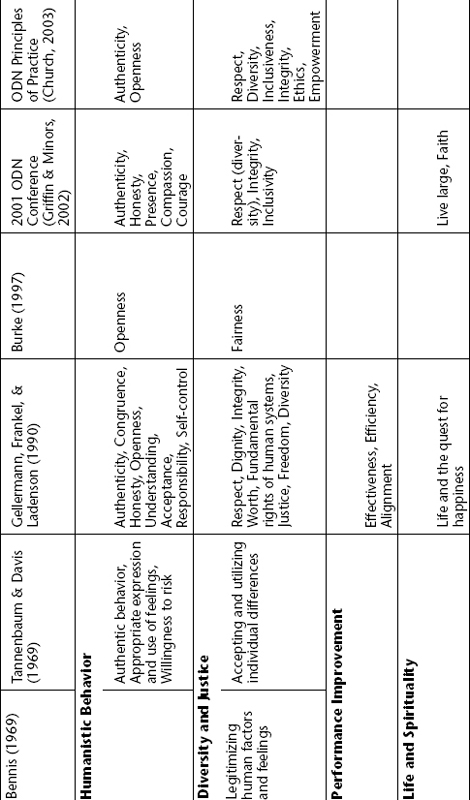

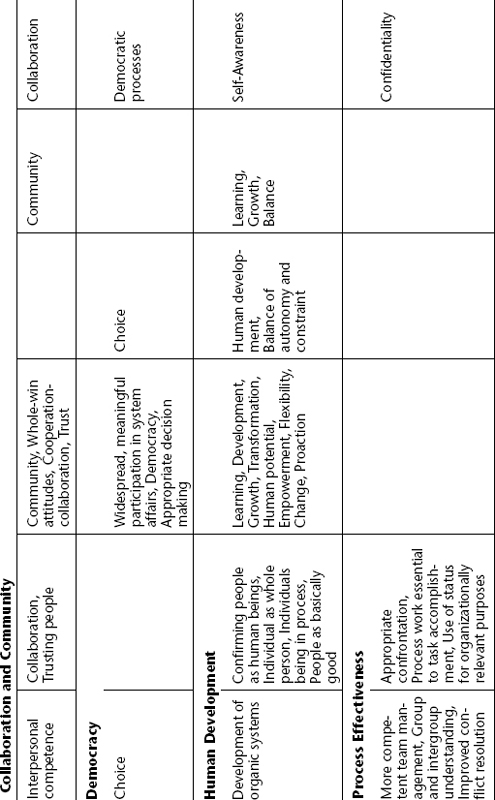

OD values are traced in this section from the formative days of OD to today. Different views of OD values over this time period are shown in Table 3.1, loosely organized along common themes and similarities.

TABLE 3.1. ORGANIZATION DEVELOPMENT VALUES AND VALUE THEMES OVER TIME

Values and the Formative Years of OD: 1950s and 1960s

The early, espoused values of OD were humanistic, democratic, and developmental in nature. The emphasis was clearly on human-social aspects as opposed to a technical-production focus. Yet the early OD pioneers had not lost sight of effectiveness, performance, productivity, and efficiency. As Bennis (1969) stated, “More often than not, change agents believe that realization of these values will ultimately lead not only to a more humane and democratic system, but to a more efficient one.” Argyris (1962) further emphasized, “Without interpersonal competence or a ‘psychologically safe’ environment, the organization is a breeding ground for mistrust, intergroup conflict, rigidity . . . which in turn leads to a decrease in organizational success in problem-solving.” French and Bell (1999), in their historic view of organization development, state, “We think most organization development practitioners held these humanistic and democratic values with their implications for different and ‘better’ ways to run organizations and deal with people.”

The earliest values, philosophy, and methods were influenced by findings from the behavioral sciences and leading management researchers who brought the whole person, social systems, democracy, and development to center stage and highlighted their impact on behavior and performance in organizations (French & Bell, 1999). The threads that began to be woven together by early OD pioneers formed the fabric for a new value-set and a different view of organizations. These threads are represented by:

- The early work of Follett (1924, 1942) advocating participative leadership and joint problem-solving by labor and management;

- (b) (b) the later work of Lewin, Lippitt and White (1939) demonstrating that democratic leadership was superior to authoritarian or laissez-faire leadership in affecting group climate and performance and Likert’s (1961) later research showing the superiority of democratic leadership;

- The Hawthorne Studies and their profound effect on people’s beliefs about organizational behavior, including the primacy of social factors on productivity and morale, that whole people come to work with feelings and attitudes that influence their performance, and that group norms have a powerful effect on productivity (Homans, 1950; Mayo, 1933, 1945; Roethlisberger & Dickson, 1939). The human relations movement grew out of this work, bringing greater attention to participative management, workers’ social needs, and training in interpersonal skills;

- Lewin’s and others’ work on group dynamics (Cartwright and Zander, 1953; Lewin, 1947a, 1947b);

- The laboratory training movement, spearheaded by Bradford, Gibb, and Benne (1964), taught people how to improve interpersonal relations, increase self-awareness, and understand group dynamics (Schein & Bennis, 1965);

- Rogers’ work that advocated self-responsibility for behavior and growth; supportive, caring social climates; and effective interpersonal communications (Rogers, 1951);

- The later work depicting a range of leadership styles, from authoritative to participative, with varying uses, pros and cons (Tannenbaum & Schmidt, 1973);

- The early work by Trist and Bamforth (1951) demonstrating the socio-technical nature of organizations;

- The new views of the person articulated by Maslow (1954), McGregor (1960), and Argyris (1957), which shifted thinking about the nature of the person/worker, motivation, and the inherent conflict between worker needs and organization needs;

- Burns and Stalkers’ (1961) work on differentiating mechanistic and organic structures and their relevance in different environments; and

- The influence of Katz and Kahn (1966), who first presented the organization as an open system.

From these research and theory contributions, the early values and philosophy of the field were created, leading to radically different strategies and methods for improving organizations and for improving people’s lives in organizations—for example, sensitivity training, T-groups, team building, socio-technical work design, and survey feedback.

Bennis (1969) and Tannenbaum and Davis (1969) provided some of the earliest descriptions of OD values. Bennis (1969) identified a set of OD values and concluded that choice is the central value of OD. Tannenbaum and Davis (1969) focused on the shift in values represented by the new field of OD and provided a more extensive list of values. Both of their lists of OD values are shown in Table 3.1.

Values and the Expanding View of OD: 1970s, 1980s, and Beyond

While the earliest efforts focused heavily on the individual and on interpersonal relations, by the 1980s OD was squarely focused in larger systems from teams to organizations and beyond to communities and societies. Tannenbaum, Margulies, Massarik, and Associates (1985) captured this expanding view of OD from “individuals” to “organizations” to “human systems” and recognized that organizations are human systems and are also subsystems of larger human systems. Experience with “T-groups” and “sensitivity training” showed that individuals can learn about themselves and group dynamics directly from their experience in groups. From this came the recognition that to improve work group functioning practitioners needed to help people who work together and learn together as a group, hence “team building.” From this it followed that the focus needed to expand to include entire organizations, hence “organization development.” And then, beyond organizations, it needed to include all the “human systems” of which societies are subsystems and ultimately our entire global human system.

Thinking of OD in terms of all levels of human systems broadens the scope and complexity of change and compounds the role of values and ethics in our work. With more stakeholders, perspectives, points of view, and agendas, it is often more difficult to determine common good, equity, and justice. Different values often drive different beliefs about what’s ethical. However, it doesn’t change the desire to use OD’s basic values or the effectiveness of changes, consistent with these values, in bringing about sustainable results in all human systems.

While OD is not considered by many to be a formal profession—with clear standards of practice, competencies, agreed values, and a code of ethics—many agree, as first suggested by Dick Beckhard, that OD is a “field of practice” and that OD practitioners operate as a “community of professionals.” There was the sense that emerged during the early 1980s that the community of OD practitioners could function more effectively with clarified values and ethics and shared knowledge and principles of practice. So a project was started to develop a statement of values and ethics for professionals in organization and human systems development (OD/HSD).

This project to develop a “statement of values and ethics by professionals in organization and human systems development” was approached, not as a set of “shoulds” to be imposed on practitioners, but as a resource for practitioners to use to clarify their own values and ethics. The process was initiated by the Organization Development Institute in 1982. Support was given by most of the leading OD-oriented networks, associations, and societies and more than one thousand OD practitioners from around the world. The project involved drafting a “statement,” distributing it for comment, revising it based on the comments, and repeating the cycle of drafting, distributing, and revising more than twenty-five times. The statement has been endorsed as a “working statement” by approximately fifty leaders in the OD community.

Since 1990, the statement has changed little and has been published in both Values and Ethics in Organization and Human Systems Development (Gellermann, Frankel, & Ladenson, 1990) and the Handbook of Organizational Consultation (Golembiewski, 2000). It stands today as the most comprehensive, widely accepted set of values in the OD/HSD field and continues to serve as the foundation of the new International Society for Organization Development’s Code of Ethics (www.theisod.org/code.htm). ISOD is the successor organization to the OD Institute.

Core Values of OD/HSD

Reviewing all of the versions of OD/HSD values identified so far, we identify the core values as follows:

- Fundamental values

- Life and the quest for happiness: people respecting, appreciating, and loving the experience of their own and others’ being while engaging in the pursuit of happiness, conceived as in the Declaration of Independence, namely “a whole life well lived.”

- Freedom, responsibility, and self-control: people experiencing their freedom, exercising it responsibly, and being in charge of themselves.

- Justice: people living lives whose results are fair and equitable.

- Personal and interpersonal values (may also be larger system values)

- Human potential and empowerment: people being healthy and aware of the fullness of their potential, realizing their power to bring that potential into being, growing into it, living it, and generally doing the best they can, both individually and collectively.

- Respect, dignity, integrity, worth and fundamental rights of individuals and other human systems: people appreciating one another and their rights as human beings, including life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.

- Authenticity, congruence, honesty and openness, understanding, and acceptance: people being true to themselves, acting consistently with their feelings, being honest and appropriately open with one another (including expressing feelings and constructively confronting differences), and both empathizing with, understanding, and accepting others who do the same.

- Flexibility, change and proaction: people changing themselves on the one hand and acting assertively on the other in a continuing process whose aim is to maintain or achieve a good fit between themselves and the external reality within which they live, including other beings.

- System values (may also be values at personal and interpersonal levels)

- Learning, development, growth, and transformation: people growing in ways that bring into being greater realization of their potential, individually and collectively.

- Whole-win attitudes, cooperation-collaboration, trust, community and diversity: people caring about one another and working together to achieve results that are good for everyone (individually and collectively), experiencing the spirit of community and honoring the diversity that exists within our global community.

- Widespread, meaningful participation in system affairs, democracy, and appropriate decision making: people participating as fully as possible in making the decisions that affect their lives.

- Effectiveness, efficiency, and alignment: people achieving desired results with an optimal balance between results and costs, and doing so in ways that coordinate the energies of systems, subsystems, and macro-systems—particularly the energies, needs, and desires of the human beings who comprise those systems.

(Adapted from Gellermann, Frankel, & Ladenson, 1990, pp. 375–376.)

The original values from Gellermann, Frankel, and Ladenson are listed in Table 3.1 together with other versions of OD values that Burke (1997), Griffin and Minors (2002), and Church (2003) suggested.

The Erosion of Core Values: 1990s

From a strong showing in the formative years (1950s and 1960s) and growth into the 1970s and 1980s, many have expressed concern over the past twenty years that “OD has lost its way” or that “practitioners [have] apparent amnesia regarding the values that underlie the field” (Burke, 1998). As the number of practitioners has grown and approaches have proliferated, some new values have come to guide OD practice. Some contradict and conflict, some undermine, and some just distract from earlier OD values. For example, some values that have proliferated in organizations contradict and undermine humanistic, democratic, and developmental values, including profit over people, dehumanizing practices in downsizing and layoffs versus humane treatment, “doing to” instead of “doing with,” efficiency at all costs, withholding information, manipulation, coercion instead of sharing, involving, or allowing for free choice.

There is no one universally acceptable set of values. So it becomes even more important for OD practitioners to be clear about the value-bases of the choices they make. Church (1996) suggested a duality has emerged in OD and that only two primary value constraints underlie OD practitioners’ work with organizations: (1) fostering humanistic concerns and (2) focusing on more traditional business issues including effectiveness, efficiency, and the bottom line. He concludes that economic pressures and issues are driving clients and the consultants they hire toward economic values, often at the expense of humanistic, democratic, developmental values. In fact, many major corporations (including about three hundred of the Fortune 500) are required by their state-granted charters of incorporation to maximize value for shareholders. Similar dynamics exist even without an economic motive. Senior managers can place higher priority on self-enhancing values over the welfare of other stakeholders. Power, prestige, control, reputation, promotion, and competition for funding can create the same value conflicts and dilemmas as the drive for profit.

This multiplicity of values was present in the beginning of organization development and continues today. Balancing the many sets of values is what has made OD a significant improvement over the prevailing thinking sixty years ago. Perhaps the humanistic, individual focus was over-emphasized. Perhaps others pushed business issues and short-term economic results to an eager audience who pressured for such results. And so the duality became an unrealistic dichotomy—an “either-or” choice, rather than “both-and.”

OD practitioners can resolve many of the differences inherent in the dichotomous either-or, short-term thinking involved in the question of economic interests versus humanistic, democratic interests. The renewed interest in corporate social responsibility, the development of new economic models that include a triple bottom line (Willard, 2002), and the radically optimistic notion that business can be an agent of world change suggest that the economic and humanistic perspectives are not fundamentally incompatible. Resolution of the apparent conflict between these views is essential for grounding organizational effectiveness in authentic human commitment, rather than coerced compliance. True value conflicts will always exist as long as people and situations continue to differ. Yet, better results can be produced by not creating dichotomous thinking out of competing values. Polarity theory (Johnson, 1996) teaches that natural polarities exist everywhere and require managing the tensions and balancing actions to achieve most of the upsides and minimize most of the downsides of those polarities.

Renewed Interest in Values: 2000s

A resurgence of interest in values has emerged in recent years, in much the same way OD formed—as a response to prevailing undesirable trends. People are being right-sized and reengineered; short-term economic indicators have become the Holy Grail; optimizing one organization at the expense of others has become common practice; short-term success and profit are overshadowing environmental deterioration and resource depletion. Values such as spirituality and community are gaining voice, sustainability is increasing, and many human potential/personal development values are reemerging. Many in OD are re-asserting core values or yearning for their return. OD is a field that must struggle for balance among often-conflicting values and manage inevitable pendulum swings.

Participants at the 2001 OD Network Conference joined in a value identification exercise about what they thought was the most important value to focus on in the coming year. The results are reported in Table 3.1. Participants identified: authenticity, respect/diversity, honesty/integrity, balance, presence, learning/growth, community/inclusivity, compassion, live large, faith, and courage (Griffin & Minors, 2002).

Subsequently, a project was launched by the ODN to identify current values operating in the field through the use of scenarios with focus groups across the United States. This effort resulted in an extensive summary of values/principles (Griffin & Minors, 2002) and a draft statement of Principles of Practice (Church, 2003). Extracting the value statements from this work produced the following values seen as important to the participants in this project: authenticity/openness, respect/diversity/inclusiveness, integrity/ethics, collaboration, democratic processes, empowerment, self-awareness, and confidentiality (Church, 2003). These values are also listed in Table 3.1 along with the other lists of OD values described earlier in this chapter.

The statements of OD values shown in Table 3.1 were developed over more than a forty-year time period. While there are some differences among the lists, the high degree of similarity is striking. These similarities suggest that there have always been central values that differentiated OD from other ways of managing and changing. That does not mean these values always operate. Individual practitioners make choices that support or undermine them. As years of OD practice and changing organizational environments have unfolded, many of the original values have eroded for some practitioners and been strengthened for others.

Ethics, Ethical Dilemmas, and Ethical Competence

Values, which are “standards of importance,” have been emphasized up to this point. Ethics are also important. They are “standards of good and bad behavior based on values.” Metaphorically, ethics are like a compass that gives us direction, while values are like magnetic north that draws the compass needle in that direction. Ethics, based on values, help OD practitioners guide themselves as they move along the paths of their work and lives. An example of a statement of OD ethics can be found in “A Statement of Values and Ethics by Professionals in Organization and Human Systems Development” (Gellermann, Frankel, & Ladenson, 1990, pp. 378–388). The ethics in this statement include:

- Responsibility to Ourselves

- Acting with integrity and authenticity.

- Striving for self-knowledge and personal growth.

- Asserting individual interests in ways that are fair and equitable.

- Responsibility for Professional Development and Competence

- Accepting responsibility for the consequences of our acts.

- Developing and maintaining individual competence and establishing cooperative relations with other professionals.

- Recognizing our own needs and desires and dealing with them responsibly in the performance of our professional roles.

- Responsibility to Clients and Significant Others

- Serving the long-term well-being of our client systems and their stakeholders.

- Conducting ourselves honestly, responsibly, and with appropriate openness.

- Establishing mutual agreement on a fair contract.

- Responsibility to the OD-HSD Community

- Contributing to the continuing professional development of other practitioners and the field of practice.

- Promoting the sharing of professional knowledge and skill.

- Working with other professionals in ways that exemplify what the profession stands for.

- Social Responsibility

- Acting with sensitivity to the consequences of our recommendations for our client systems and the larger systems within which they are subsystems.

- Acting with awareness of our cultural filters and with sensitivity to multinational and multicultural differences and their implications.

- Promoting justice and serving the well being of all life on earth.

(Adapted from Gellermann, Frankel, & Ladenson, 1990, pp. 378–388.)

OD work involves confronting many situations that pose ethical dilemmas. Egan and Gellermann (2005) suggest that ethical dilemmas in OD are created through the conflict between competing rights, obligations, and interests. White and Wooten (1983), Gellermann, Frankel, and Ladenson (1990), DeVogel (1992), and Page (1998) have identified ethical dilemmas experienced by OD practitioners:

- Misrepresentation and collusion—including the illusion of participation, clients presenting partial pictures, or adopting the clients’ biases;

- Misuse of data—including sharing confidential information or presenting partial data to support a prior conclusion;

- Manipulation and coercion—including using undue practitioner influence, a client misleading a practitioner, or incorporating inappropriate threats and rewards to reach certain outcomes;

- Value and goal conflicts—including differences on means or ends with clients or differences with a co-practitioner;

- Technical ineptitude—including inappropriate intervention, shortchanging diagnosis, or working beyond one’s competence, and

- Client dependency—including clients needing too much of the practitioner’s help or the practitioner not helping the client to learn and develop capabilities.

In recent years another ethical issue has emerged involving intellectual honesty. Concepts, ideas, models, and tools with lineage to founders and other practitioners are showing up, in various forms, in presentations, handouts, PowerPoint presentations, and even books with no reference to the creators and the presumption that they were created by the current author. Another variation, in highly commercial enterprises, involves slight changes to someone’s previous work with a new author’s copyright. These practices are unethical and disrespectful of the community of OD practitioners.

Being aware of these ethical issues helps OD practitioners recognize and respond to them.

A recent article on the future of OD (Worley & Feyerherm, 2003) suggests that OD is experiencing a period of confusion and ambiguity about values. Practitioners are in the position of having to rely on their own value bases and individual ethical frameworks, rather than on generally agreed-on ethical standards. In these circumstances, ethical behavior depends on the decision making of each OD practitioner and the values used in conflicting situations. It is therefore critically important that practitioners develop ethical competence, which DeVogel (1992) believes is a function of the extent to which practitioners have:

- “Informed their intuition” with a clear understanding of their own beliefs, values, ethics, and potential ethical challenges;

- Reflected on their experiences to create a knowledge base for future action; and

- Practiced the use of values and ethics in a way that makes them available when they are needed, that is, developed and implemented a model of ethical decision making.

In the absence of such development and personal clarity, practitioners run the risk of drifting towards a form of unexamined self-interest (Egan & Gellermann, 2005).

Ethical competence and capacity is developed through reflective practice (Schön, 1983). Because there are never “right or wrong” choices, the ability of OD practitioners to know what to do is dependent on how well they learn from experience and build a knowledge base and decision-making competence through continued reflection and personal conclusion. One way of developing ethical competence is to review the situations cited in the references listed in this section and to reflect on one’s own response to those situations.

Evolving Values in a Continuously Changing Future

Values and ethics and how they relate to the practice of OD have been discussed in this chapter. They are continually evolving, just as organizations, environments and practitioners all keep changing. We hope this evolution will be guided by consciously chosen values and ethics consistent with Bennis’ (1969) notion that choice is the central value of OD.

Because OD is based on particular values, the field is not for everyone. Practitioners need to assess who they are, their alignment with the set of values generally seen as the foundation of OD, and their commitment to working with processes, principles, and methods that are consistent with those values.

The central requirements for being an OD practitioner are described below, based on the key value themes from this chapter. A practitioner’s purpose needs to focus on service to others. One needs to care for the well being of all human systems and strive for their growth and development of potential. And while the field may work with larger and larger systems—and ultimately the global system—there will always need to be concern for the individual and for quality of life. Additionally, one needs to believe in the use of self as the instrument of change in helping others. What OD practitioners bring of themselves in engaging with clients plays an enormous role in what actually transpires in the practice of OD.

Most OD values involve personal conduct and how practitioners work with others. It is important to:

- Strive for authenticity, congruence, openness, and wholeness;

- Be who we really are and not a set of personas;

- Acknowledge the whole person—intellectual, emotional, spiritual, physical—and his or her complexity;

- Model open exchange between people that leads to deeper understanding;

- Strive for integrity and to operate in a fair and just manner;

- Be accountable and trustworthy;

- Keep all stakeholders in mind;

- Ensure equitable treatment and unbiased justice;

- Include differences with respect and dignity; and

- Believe in the value and rights of diversity.

Being an OD practitioner requires constantly seeking the balance needed for being a whole person, between individual and organizational needs, between performance and humanness, and between content and process. More than most fields, OD looks for the common ground, the balance, the both-and, the win-win solution.

In the practice of OD a context of democracy is important that empowers people to participate with free choice and responsibility. To develop processes and structures that build people’s involvement in their destiny and hold people accountable for their actions and decisions. To work in OD is also to utilize the power of the group and facilitate interpersonal competence, cooperation, collaboration, and synergy. And to build jointness—collective and community—into the mindset of the human system.

These purposes and values are the desired intention and require serious commitment. They are the foundation for OD practice and the hope for clients and all levels of human system. They represent desired outcomes of work with others and they provide the rudder for navigating through practitioners’ lives. Values and ethical behavior are so central for OD that all practitioners must look inside, become clear about their purpose, values, and ethics, and translate that understanding into the way they live their lives.

Where Do We Go from Here?

Since the first publication of this handbook, it is gradually becoming clear to some practitioners within the field of OD/HSD, including the authors of this chapter, that our profession can benefit by operating less as a collection of independent individuals and more as a collaborative network/community of professionals who are aligned on serving our entire global community. More and more issues have arisen relating to larger scale human systems—such as inter-organizational arrangements, communities, nations, societies, regions and our whole Earth—and our field of practice can no longer be focused only on single organizations (although individual practitioners may do so) or be practiced independently. Thus, we need to use our values and shared ethics to strengthen and expand our community of practitioners in cooperative action, including expanding the focus of our practice to include comprehensive human systems. This seems feasible if we are able to apply our principles and practices to ourselves, work collaboratively as we do with clients, and involve our professional associations and networks in developing ourselves as a human system.

References

Argyris, C. (1957). Personality and organization. New York: Harper & Row.

Argyris, C. (1962). Interpersonal competence and organizational effectiveness. Homewood, IL: Irwin-Dorsey.

Bennis, W. G. (1966). Changing organizations. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Bennis, W. G. (1969). Organization development: Its nature, origins and prospects. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

Bradford, L. P., Gibb, J., & Benne, K. D. (1964). T-group theory and laboratory method: Innovation in re-education. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Burns, T., & Stalker, G. (1961). The management of innovation. London: Tavistock.

Burke, W. W. (1992). Organization development: A process of learning and changing (2nd ed.). Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

Burke, W. W. (1997). The new agenda for organization development. Organizational Dynamics, 26(1), 7–20.

Burke, W. W. (1998, Spring). Living OD values in today’s changing world of organization consulting. Vision/Action, 17, 1.

Church, A. (1996, Winter). Values and the wayward profession: An exploration of the changing nature of OD. Vision/Action, 15, 4.

Church, A. (2003). Principles of practice of OD. Unpublished document. Organization Development Network.

Cartwright, D., & Zander, A. (1953). Group dynamics: Research and theory. Evanston, IL: Row, Peterson & Company.

DeVogel, S. (1992). Ethical decision making in organization development: Current theory and practice. Unpublished dissertation. University of Minnesota.

Egan, T., & Gellermann, W. (2005). The ethical practitioner. In W. Rothwell, R. Sullivan, & G. McLean (Eds.), Practicing organization development (2nd ed.). San Francisco, CA: Pfeiffer.

Follett, M. (1924). Creative experience. New York: Longmans, Green.

Follett, M. (1942). Dynamic administration: The collected papers of Mary Parker Follett. H. Metcalf & L. Urwick (Eds.). New York: Harper & Row.

French, W., & Bell, C. H., Jr. (1999). Organization development: Behavioral science interventions for organization improvement (6th ed.). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Gellermann, W., Frankel, M., & Ladenson, R. (1990). Values and ethics in organization and human systems development. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Golembiewski, R. (Ed.). (2000). Handbook of organizational consultation (2nd ed.). New York: Marcel Dekker.

Griffin, P., & Minors, A. (2002). Values in practice in organization development: An interim report. Unpublished document, Organization Development Network.

Homans, G. (1950). The human group. New York: Harcourt, Brace, Jovanovich.

Hultman, K., & Gellermann, W. (2001). Balancing individual and organizational values: Walking the tightrope of success. San Francisco, CA: Pfeiffer.

Jamieson, D. (2003). The heart and mind of the practitioner: Remembering Bob Tannenbaum. OD Practitioner, 35(4), 3–8.

Jamieson, D., Auron, M., & Shechtman, D. (2010). Managing “use of self” for masterful professional practice. OD Practitioner, 42(3), 4–11.

Johnson, B. (1996). Polarity management: Identifying and managing unsolvable problems. Amherst, MA: HRD Press.

Katz, D., & Kahn, R. (1966). The social psychology of organizations (2nd ed.). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Lewin, K. (1947a). Frontiers in group dynamics, Part I: Concept, method and reality in social science: Social equilibria and social change. Human Relations, 1, 5–41.

Lewin, K. (1947b). Frontiers in group dynamics, Part II: Channels of group life: Social planning and action research. Human Relations, 1, 143–153.

Lewin, K., Lippitt, R. O., & White, R. (1939). Patterns of aggressive behavior in experimentally-created social climates. Journal of Social Psychology, 10, 271–299.

Likert, R. (1961). New patterns of management. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Maslow, A. (1954). Motivation and personality. New York: Harper & Row.

McGregor, D. (1960). The human side of enterprise. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Mayo, E. (1933). The human problems of an industrial civilization. New York: Macmillan.

Mayo, E. (1945). The social problems of an industrial civilization. Boston, MA: School of Business Administration, Harvard University.

Page, M. (1998). Ethical dilemmas in organization development consulting practice. Unpublished master’s thesis. Pepperdine University.

Rogers, C. (1951). Client-centered therapy. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin.

Roethlisberger, F., & Dickson, W. (1939). Management and the worker. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Schein, E. H., & Bennis, W. G. (1965). Personal and organizational change through group methods: The laboratory approach. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Schön, D. (1983). The reflective practitioner: How professionals think in action. New York: Basic Books.

Stiglitz, J. (2012). The price of inequality: How today’s divided society endangers our future. New York: W.W. Norton & Company.

Tannenbaum, R., & Davis, S. (1969). Values, man, and organizations. Industrial Management Review, 10(2), 67–86.

Tannenbaum, R, Margulies, N., Massarik, F., & Associates (1985). Human systems development: Perspectives on people and organizations. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Tannenbaum, R., & Schmidt, W. (1973). How to choose a leadership pattern. Harvard Business Review, 51, 95–102.

Trist, E., & Bamforth, K. (1951). Some social psychological consequences of the longwall method of coal-getting. Human Relations, 4(1).

White, L., & Wooten, K. (1983). Ethical dilemmas in various stages of organization development. Academy of Management Review, 8, 690–697.

Willard, B. (2002). The sustainability advantage: Seven business case benefits of the triple bottom line. Gabriola, BC, Canada: New Society Publishers.

Worley, C. G., & Feyerherm, A. (2003). Reflections on the future of organization development. Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 39(1), 97–115.