CHAPTER SIXTEEN

ORGANIZATION LEADERSHIP

Leading in a Learning Way

Mary Ann Rainey and David A. Kolb

A constantly changing environment is one of the most daunting challenges facing organizations today. When organizations are confronted with difficult challenges, learning becomes the best option for leadership. We use experiential learning theory (Kolb, 1984) as the epistemological lens through which to establish leadership as a wholly integrated process of learning and adaptation. When defined holistically as the basic means by which humans adapt to the world, learning subsumes the process of leadership. We introduce the Relationship Strategy Vision Performance (RSVP) Fundamentals of Leadership Model. Based on experiential learning theory (ELT), the RSVP Model is a typology of four essential functions—Relationship Mastery, Strategy Mastery, Vision Mastery, and Performance Mastery—that represent an adaptive approach to leadership. For effective leadership to occur, leaders must be able to execute all four functions in a way that is responsive to the context and the problem at hand. The underlying message of ELT is there is no one leadership style; rather, leadership is a multi-functional process requiring a broad range of proficiency. With ELT, organization development and human resource professionals, coaches, supervisors, and others interested in the study and practice of leadership have a theoretically sound and well-established frame of reference to guide leaders in today’s uncertain environment. Strategies for leadership education, training and development are identified.

Introduction

There are more than half a million studies, articles, and tomes on leadership, exploring topics ranging from what leadership is, how it differs from management, whether leaders are born or bred, to questioning whether leadership exists at all or is just a figment of human imagination. We are at the same time intrigued and torn by leadership that is responsible for some of history’s darkest times yet provides many of our most celebratory moments. And even in our ambivalence, we have come to rely on leadership in all aspects of our lives—at home, at work, at play, in battle, and where we pray.

Leadership has never been more critical than it is now. Organizations of all kind from the village center to the corporate chief (C-suite) are searching for more effective leadership models in an era of permanent change where dynamics are increasingly complex, proven solutions unreliable, and everyone and everything is swayed by technology.

“World-wide surveys of senior executives and human resource professionals indicate that up to 70 percent of North American employers experience a dearth of leadership talent that is and will continue to impede organizational performance. In Asia, the problem is even worse, with 88 percent of organizations indicating concern about a looming shortage of leadership talent” (Ashford & DeRue, 2012, p. 146).

When leadership is absent, it is more difficult for organizations to adapt to change, sustain super-ordinate goals and values, and instill a sense of pride of belonging among its members (Zaleznik, 1977).

Of particular significance to the study of leadership is the growing acceptance of the view of organizations as systems of learning where adaptive ability is a key driver of success. This perspective has been greatly influenced by research on experiential learning theory (Kolb 1984; Kolb & Kolb, 2005a, b). According to Heifetz and Laurie (1997), the adaptive demands of our times require leadership that is committed to learning, a point of view shared by Israeli President and Nobel laureate Shimon Peres, who believes we are in the era of learning: “The greatest branch of the economy in the future will be learning and teaching and educating. Learn more, work less. I think the proportion will change. Most of our time we will either be studying, teaching, or doing research. There is no end to learning, there is no end to research, there is no end to imagination—- and no limit to creativity” (2012, p. 3).

Larry Fink (2012), chairman and CEO of Black Rock, a global investment management firm, is of similar mind: “As you watch how so many companies have failed, they may have been very good with one product for one moment. But they didn’t monitor the evolution of that product or the evolution of that information and thus did not adapt fast enough and became irrelevant—or else their product became irrelevant. To me as a leader, that is one of the most important messages to everyone. If you think you’re not a student today and you’re not out there learning, then you’re not going to know how to govern this country” (p. 5).

However, what students of leadership are often hoping to learn is the “one best way” to lead. According to experiential learning theory (ELT), such a perspective is misguided. With more than forty years of research on learning and specialized business processes, ELT has wide-reaching ability to examine leadership as a holistically integrated composite of multiple styles that, when effectively appropriated, are more than adequate in responding to today’s adaptive challenges.

We define leadership as a process of learning and adaptation resulting from the interaction between leader(s) and follower(s) who are guided by a shared value system in service of achieving mutually beneficial goals. Leadership exists in all walks of life, cultures, sectors, and levels of organization, whether under cover of authority or not.

Several key assumptions underpin this writing:

- Leadership is a holistic process of learning and adaptation.

- Leadership requires the resolution of conflicts between dialectically opposed modes of adaptation to the world.

- Leadership is a social process that involves interaction between leader and follower.

- Leadership is multi-functional, requiring a broad range of competence.

First, we will provide an overview of leadership thought, followed by a review of basic concepts of Kolb’s ELT. Leadership and learning come together in the presentation of the relationship strategy vision performance (RSVP) fundamentals of leadership model, a holistic and integrated typology of leadership associated with the phases of the experiential learning cycle. We will conclude with strategies for leadership education, training, and development using the model.

Leadership Thought

Perspectives on leadership can be traced to the ancient writings of Chinese general Sun Tzu in The Art of War and the treatises of Greek philosopher Aristotle. However, it was not until the second quarter of the 20th century that leadership gained traction as a field of study. Management thought appeared much sooner, growing out of the need to formalize and teach the newer methods of production created during the Industrial Revolution (Wren, 1987). For decades, management was the central focus of business education in the western world and managerial performance the exclusive point of validation for theories and concepts of organizational behavior. As understanding grew about the complex nature of work, so did awareness of the value of attending to how people were led as well as to how they were managed.

There is no one generally accepted theory of leadership. As the context of leadership has shifted, so have expectations and conceptualizations of what it is. Leadership has been defined as an inborn trait found in certain people, as the characteristics shared by those who lead, as a social process driven by the interaction between leader and follower, by what leaders do, and by the situational and environmental conditions under which work is accomplished. Transformational leadership, charismatic leadership, leaders as stewards, self-leadership, and distributed leadership are among frequently cited forms of leadership currently gaining attention.

Much of the literature on leadership is devoted to comparisons between leadership and management. In an effort to differentiate between management and leadership, Burns (1978) compared ordinary (transactional) leaders, who exchange tangible rewards for the work and loyalty of followers, and extraordinary (transforming) leaders, who engage with followers, focus on higher order intrinsic needs, and raise consciousness about the significance of work. According to Kotter (1990), both management and leadership are important in large organizations with a dynamic environment; that as an organization becomes larger and more complex, the need for management increases and as the external environment becomes more dynamic and uncertain, leadership becomes more important.

Heifetz and Laurie (1997) believe the most important quality in leadership today is competence in “adaptive change,” which they define as the sort of change where organizations are forced to adjust to a radically altered environment: “Adaptive work is required when our deeply held beliefs are challenged, when the values that made us successful become less relevant, and when legitimate yet competing perspectives emerge. We see adaptive challenges every day at every level of the workplace—when companies restructure or reengineer, develop or implement strategy, or merge businesses. We see adaptive challenges when marketing has difficulty working with operations, when cross-functional teams don’t work well, or when senior executives complain, ‘We don’t seem to be able to execute effectively.’ Adaptive problems are often systemic problems with no ready answers.” (p. 124)

Experiential Learning Theory

There is a long history of experiential learning methods in leadership education dating back to the popularity of Kurt Lewin’s laboratory training group (T-group) methods for teaching group dynamics in the 1960s. Although the classic T-group technology has diminished in use, training programs and courses based on experiential learning are widespread and commonplace. Kolb (1984) draws on the work of Lewin and other prominent 20th century scholars, such as John Dewey, Jean Piaget, William James, Carl Jung, Paulo Freire, Carl Rogers, to develop ELT, a theory that defines learning as the major process of human adaptation involving the integrated functioning of the total person—feeling, perceiving, thinking, and doing. The holistic nature of ELT makes it applicable beyond the classroom. Research in ELT is highly interdisciplinary, addressing learning and education issues in many fields (Kolb & Kolb, 2006). Studies using ELT have examined many aspects of diversity (e.g., Rainey & Kolb, 1995) and have been conducted around the world supporting the cross-cultural applicability of the model. Basic concepts of ELT, the learning cycle, learning styles, learning space, learning skills, are used in this article.

The Experiential Learning Cycle

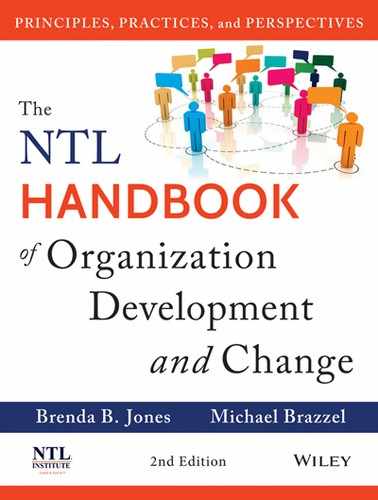

In ELT, learning proceeds as a recursive cycle or spiral and results from the integration of four learning modes: concrete experience, reflective observation, abstract conceptualization, and active experimentation (see Figure 16.1). Learners must be able to fully and openly engage in new concrete experiences; reflect on, observe, and consider these experiences from various perspectives; create concepts that assimilate these experiences into sound theories; and, appropriately apply these theories to their life situations. Learning results from the dynamic tension created by the interplay among the four learning modes which are dialectically positioned along two primary dimensions of knowledge. Grasping, knowing by taking in experience, includes concrete experience and abstract conceptualization. Transforming, knowing through modification of data, includes reflective observation and active experimentation.

FIGURE 16.1. THE EXPERIENTIAL LEARNING CYCLE

Source: Kolb, 1971.

Learning Styles

The concept of learning style describes the preferred approach an individual holds for resolving the conflicts between concrete and abstract and between reflection and action. These stylistic preferences arise from the patterned ways learners choose between the polarities of experiencing-thinking and reflecting-doing. Learning patterns ultimately influence how one views current situations and perceives and decides future choices. Early research defined four learning style types—accommodating, diverging, assimilating, and converging. Additional research and feedback from individual users indicated that the division of the learning space into four regions was problematic for some and categorized their learning style in a way that was misleading. Further investigation revealed that these borderline cases were actually distinct styles in themselves, resulting in the creation of the following nine style typology (Kolb & Kolb, 2005a):

- Initiating style is distinguished by the ability to initiate action to deal with experiences and situations.

- Experiencing style is distinguished by the ability to find meaning from deep involvement in experience.

- Creating style is distinguished by the ability to create meaning by observing and reflecting on experiences.

- Reflecting style is distinguished by the ability to connect experience and ideas through sustained reflection.

- Analyzing style is distinguished by the ability to integrate and systematize ideas through reflection.

- Thinking style is distinguished by the capacity for disciplined involvement in abstract reasoning, mathematics, and logic.

- Deciding style is distinguished by the ability to use theories and models to decide on problem solutions and courses of action.

- Acting style is distinguished by a strong motivation for goal directed action that integrates people and tasks.

- Balancing style is distinguished by the ability to flexibly adapt by weighing the pros and cons of acting versus reflecting and experiencing versus thinking.

Knowledge of one’s preferred style of learning enhances self-awareness and influences the way in which one approaches work, manages emotions and communicates with others. Individuals can change and expand their preferred learning style to become flexible in order to adapt to situational needs. The Kolb Learning Styles Inventory 4.0 (Kolb & Kolb, 2011) is a tool designed to increase self-awareness of learning style and learning flexibility.

Learning Space

The idea of learning space builds on Lewin’s field theory and his concept of life space. For Lewin, person and environment were interdependent variables, a concept Lewin translated into a mathematical formula, B = f (p, e) where behavior is a function of person and environment and the life space is the total psychological environment which the person experiences subjectively. In ELT, the experiential learning space is defined by the attracting and repelling forces (positive and negative valences) of the two poles of the dual dialectics of experiencing-thinking and reflecting-doing.

Organizational Learning

At the organizational level, learning is a process of differentiation and integration focused on mastery of the organizational environment (Kolb & Kolb, 2009). The organization differentiates itself into specialized units charged with dealing with one aspect of the organizational environment. For example, marketing deals with the market and customers, research and development with the academic and technological community, manufacturing with the production of consumer goods and products. This creates a corresponding internal need to integrate and coordinate the specialized units. Too often this integration is achieved through domination of one functional mentality in the organization culture. Leadership is one of the numerous ways organizations achieve integration. The role of leadership is to resolve internal conflicts between specialized units and achieve a coherent direction for the organization. It is with integration that leaders can get the broadest range of knowledge and support to respond to adaptive challenges.

Relationship, Strategy, Vision, Performance Fundamentals of Leadership

An age-old question in the annals of leadership is whether there is one leadership style. The response of ELT is leadership is an adaptive process anchored in learning that is suitable for a range of experience and positions the most skilled with the situation at hand. In actuality, this means that any style will be a leading style in the right context.

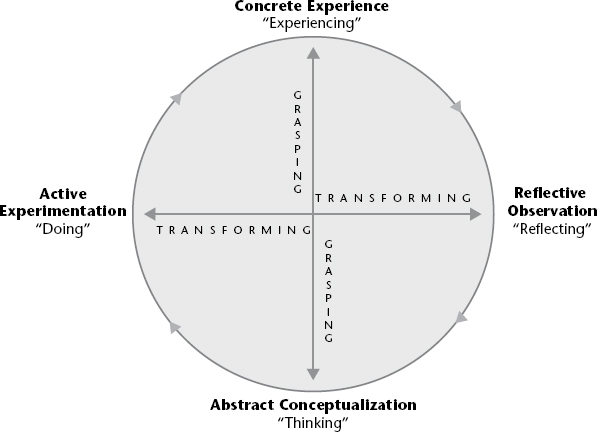

The RSVP Model identifies the primary components of integrated leadership practice. Similar in structure to the experiential learning cycle, the model consists of four leadership activities positioned along two dimensions. Relationship mastery and strategy mastery make up the north/south dialectic dimension and correspond to concrete experience and abstract conceptualization. Vision mastery and performance mastery make up the east/west dialectic dimension and correspond to reflective observation and active experimentation. Effective leadership requires the ability to touch all four bases and the flexibility of learning to lead individuals, groups, and teams around the learning/leadership cycle. (See Figure 16.2.)

FIGURE 16.2. THE RSVP FUNDAMENTALS OF LEADERSHIP

Relationship Mastery

Note: The term “mastery” is used to suggest a higher level of competence. Senge (1990) identifies five disciplines of the learning organization: personal mastery, mental models, building shared vision, team learning, and systems thinking. Personal mastery is the discipline of continually and deepening personal vision, of focusing energy, of developing patience and seeing reality objectively.

Leadership is a role. Leadership is also an enactment. Those who lead do so in relation to others. This social constructionist perspective means that leadership must forge and sustain healthy relationships with its constituent community. Relationship building is directly tied to the leader’s ability to communicate, build trust, and inspire others to commit to the vision, strategy, and goal achievement. With an emphasis on rationalism, early management thought did not assign a place for the human side of enterprise. Wider receptivity of subjective experience in the workplace came with the publication of the Harvard Business Review article, “Emotional Intelligence,” by Daniel Goleman (1995). The author positioned emotional intelligence (EI) at the core of effective leadership and identified four overarching components: self-awareness, self-management, awareness of others and relationship management. According to Goleman, EI makes a measurable difference in leader and follower bottom-line performance. His findings have been confirmed in other independent research in the United States, Europe, and Asia. (See Exhibit 16.1, Relationship Box.)

In the current era of social networks, it is clear that good relationships are influenced by systems and processes and things as well. In the new millennium, technology has become a critical player in relationship building. Leaders can use technology to build faster and more informed responses to adaptive challenges. Immediate connections can be made, including those beyond typical sources (employees, experts, competitors, suppliers), to gather data, seek opinions, and engage in conversations with people in remote parts of the world.

Strategy Mastery

Strategy is the means organizations use to bring order and direction to the way forward through the establishment of clear goals. (See Exhibit 16.2.) Standards of operation are set against which everyone, including leadership, can be held accountable. Because strategy plays such an important role in shaping organizational mindset, the strategic process must be undertaken by leadership. This is not to suggest that leadership should go it alone. Organizations are wise to open their strategy process to a cross section of the workplace but leadership must be situated at the forefront of the strategy process. In the role of strategist, leadership becomes the communicator of clear intent, which Cynthia Montgomery (2012) refers to as meaning maker: “It is the leader—the strategist as meaning maker—who must make the vital choices that determine a company’s very identity, who says, “This is our purpose, not that. This is who we will be. This is why our customers and clients will prefer a world with us rather than without us.” Others, inside and outside a company, will contribute in meaningful ways, but in the end it is the leader who bears responsibility for the choices that are made and indeed for the fact that choices are made at all” (p. 2).

Depending on the magnitude of an adaptive crisis, leaders may need to outline a supplemental strategy that is tailored to the situation at hand. Even under special circumstances, strategy must continue to rest on clear purpose and operational practicality. Thus, strategy at the level of leader becomes the compass providing direction rather than a codified pronouncement of detailed routes.

Vision Mastery

Regardless of where in the organization it exists, leadership dangles on a precipice at the border of the internal and external environment. In the role of visionary, leadership becomes a systems thinker, seeing the bigger picture and component parts both internal and external in relation to each other. Barton and colleagues (2012) report that many leaders feel the need to view “the world through two lenses: a telescope, to consider opportunities far into the future, and a microscope, to scrutinize challenges of the moment at intense magnification” (p. 10). Similarly, crafting a vision requires bifocal competence of far-sightedness and near-sightedness. Visioning is an inductive process involving reflection and contemplation in order to gain sight.

Kotter (1990) notes that most discussions of vision have a tendency to degenerate into the mystical and suggestions that vision is beyond human grasp. On the contrary, says the author, creating a vision is not magic but the tough, sometimes exhausting work of broad-based thinkers who are willing to take risks. One of the most challenging aspects of vision creation is balancing the personal dream of the leader with the aspirations of members of the organization. (See Exhibit 16.3.) As leaders seek to stay personally connected to their visions, they must be tuned to the need to cultivate followership. It is the constant tug of “I want and we need.” An equally pressing issue is assimilating various inputs into a compelling picture of the future. Vision is a finely woven tapestry of organizational purpose over the longer term that has the strength of fiber to hold together in the wake of unforeseen crises.

Performance Mastery

Like conceptions of leadership, determinants of performance differ from one school of thought to another. Most researchers evaluate leadership effectiveness in terms of the consequences of influence on a single individual, a group or team, or an organization. One common indicator of leader effectiveness is the extent to which the performance of the team or organizational unit is enhanced and the attainment of strategic goals is facilitated. Performance is the ability to deliver on the promise, whether through empowering and enabling others, enhancing quality of life, producing intended results, establishing competitive advantage or value creation. In the role of performer, leadership seeks to make a difference by producing positive results. Regardless of the objective, good performance leaves people and things feeling transformed either qualitatively or quantitatively and sometimes in joyful combination.

Performance requires leaders to take personal risks while influencing others to accompany them into unchartered waters. Adaptive work is fraught with uncertainly. Leaders will find that even at the highest levels, one of the toughest jobs is aligning stakeholder support for change (Heifetz & Laurie, 1997). Alignment is a methodical process of building stakeholder motivation and determination to work though fear and obstacles to land on the positive side of change. (See Exhibit 16.4.)

Warren Buffet is in a class by himself when it comes to return on investment. When the self-made billionaire investment guru speaks, everyone listens. But what makes Buffet special is his philanthropic efforts. In 2006, Buffett gave his entire fortune, estimated at $62 billion, to charity, the largest act of charitable giving in U.S. history. And it did not stop there for Buffet. The octogenarian is quite adept at forging relationships across generational lines, whether through his cartoon investment lessons for children or his collaboration with members of the hip-hop community. Buffet touches all the bases and best represents the consummate adaptive leader.

Strategies for Leadership Development: The Road to Mastery

According to Heifetz, Linsky, and Grashow (2009), people cannot make the adaptive leap necessary to thrive in a new environment without learning new attitudes, values, and behaviors. In their understanding, mastering change depends on the extent to which people have internalized the change itself. Leonard (1992) discovered that the road to mastery is through learning certain skills, whatever those skills might be. He discovered that mastery is not reserved for the super-talented or those born with exceptional talents; instead, mastery begins when an individual decides to learn. Central to a learning perspective on leadership is the ability to deliberately learn from experience (Kolb & Yeganeh, in press). As Ashford and DeRue put it: “To illustrate, consider the fact that leadership development programs customarily teach leadership concepts and skills, but rarely do development programs teach individuals how to learn leadership—which is ironic considering that over 70 percent of leadership development occurs as people go through the ups and downs of challenging, developmental experiences on the job. We contend that the return on investment in leadership development would be much greater if organizations invested in developing individuals’ skills related to the learning of leadership from lived experiences, as opposed to simply teaching leadership concepts, frameworks, and skills” (2012, p. 147).

The basic concepts of ELT, learning cycle, learning styles, learning space, learning skills, are a platform for RSVP coaching, executive team development and leadership development, training and education. One example comes from teaching adaptive leadership to family medicine residents: “Effective experiential learning requires flexible use of all four styles. As a result teaching leadership requires understanding a learner’s style preference and creating individualized experiences to foster flexibility. An example of this is a resident who struggled to produce a rich enough practicum proposal. Completion of Kolb’s style preference tool showed a very strong preference for concrete experience and explained why the coach’s abstract questions about organization dynamics had not stimulated reflective observation or active experimentation. This led to changes in coaching style and learner focus to incorporate increased experimentation while still encouraging the use of alternate styles” (Eubank, Geffken, Orzano, & Ricci, 2012, pp. 247–248).

Developing Relationship Mastery in Concrete Experience (Experiencing)

Relationship mastery involves a high level of emotional intelligence: direct experience with self, and engagement with others. Experience exists in the here and now. Relationship mastery is enhanced by attending to the flow of sensations and feelings and is inhibited by being too much “in your head.” Awareness and presence of mind are particularly important. Interpersonal skills, leading, relating and giving and receiving, help in developing relationship mastery.

Developing Strategy Mastery in Abstract Conceptualization (Thinking)

Strategy mastery is the ability to represent and manipulate ideas “in your head” and can be distracted by intense direct emotion and sensations as well as pressure to act quickly. Leaders must be able to generalize and make meaning of multiple inputs and represent them in a fair and judicious manner. Thinking is enhanced by theoretical model building and planning scenarios for action. Analytical skills, theory building, quantitative data analysis and technology management, are useful in developing strategy mastery.

Developing Vision Mastery in Reflective Observation (Reflecting)

Vision mastery needs space and time for the creative process to take place and can be interrupted by impulsive desires and pressures to take action. Stillness, quietness, and deep breathing help. Meditation, yoga, and journaling are beneficial practices. A high level of empathy and appreciation is important. Information skills—sense-making, information gathering and information analysis—aid in developing vision mastery.

Developing Performance Mastery in Active Experimentation (Doing)

Performance mastery calls for engagement in the practical world of real consequences and is a function of taking action. Acting can be inhibited by too much internal processing in any of the three previous modes. Acting can be enhanced by courageously taking initiative and creating of cycles of goal setting and feedback to monitor performance. Action skills, initiative, goal setting, and action taking, help in developing performance mastery.

The Learning Skills Profile (LSP)

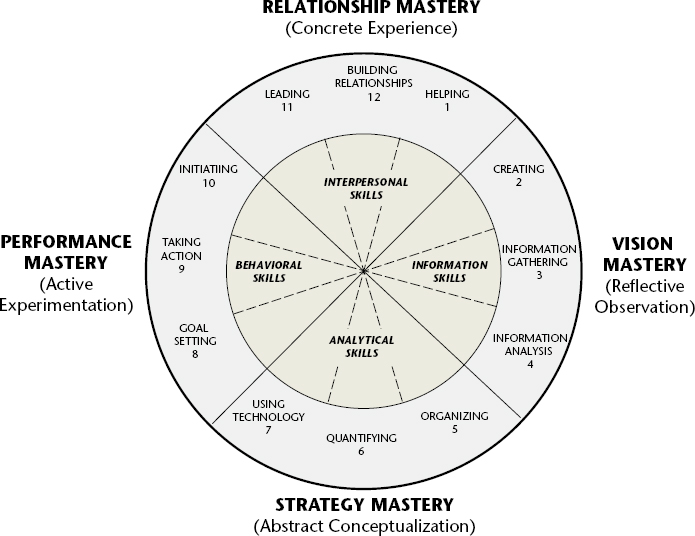

Learning styles are translated into learning skills with the Learning Skills Profile (Boyatzis & Kolb, 1991, 1995, 1997). The LSP is a practical tool that can be used for leadership development. Figure 16.3 illustrates the four skill areas of the LSP with the four fundamental areas of the RSVP model.

FIGURE 16.3. FOUR FUNDAMENTALS OF LEADERSHIP AND RELATED LEARNING SKILLS

The LSP is well suited for 360-degree assessments for management and leadership development programs (Kolb, Lublin, Spoth, & Baker, 1986); Rainey, 1991; Rainey, Hekelman, Galazka, & Kolb, 1993; Smith, 1990). It highlights which functions of the RSVP Model leaders are likely to deploy more than others. The basic protocol involves:

- Skill Level Assessment. Determine using a 7-point scale the proficiency level of the leader for each skill.

- Job Demand Assessment. Determine using a 7-point scale the extent to which each skill is a demand of the job in question.

- Gap Analysis and Developmental Planning. Construct a leadership development plan based on the gap between skill level and job demand.

Development programs should begin with the administration of the Learning Style Inventory to (a) teach leaders how to learn from experience, (b) appreciate the value of experiential learning in effectively managing today’s adaptive challenges, and (c) identify learning preferences and individual learning styles. The next step is to conduct a 360-degree assessment using the LSP.

Summary

The purpose of this chapter is to provide a perspective of leadership as a holistic and integrated process of learning and adaptation. The adaptive ability necessary for success in a world of constant change comes best from an openness and willingness of leaders to engage in continuous learning. We used key concepts of Kolb’s ELT to develop a holistic and integrated perspective of leadership. We presented the RSVP model that describes four primary functions of leadership—relationship mastery, strategy mastery, vision mastery, and performance mastery that together can steer leaders through the myriad of adaptive challenges they face in the world today. Figure 16.4 is a composite of key variables of the RSVP model. By utilizing the basic concepts of ELT—learning cycle, learning styles, learning space, and learning skills—coaches, supervisors, consultants, and trainers are equipped with a comprehensive set of tools and strategies for leadership development in the 21st century.

FIGURE 16.4. LEADERSHIP FUNDAMENTALS AND DISTINCT VARIABLES

References

Ashford, S. J., & DeRue, D. S. (2012). Developing as a leader: The power of mindful engagement. Organizational Dynamics, 41(2), 146–154.

Barton, D., Grant, A., & Horn, M. (2012, June). Leading in the 21st century: Six global leaders confront the personal and professional challenges of a new era of uncertainty. McKinsey Quarterly. www.mckinsey.com/insights/leadinginthe21stcentury.

Boyatzis, R. E., & Kolb, D. A. (1991). Learning Skills Profile. Boston, MA: TRG Hay/McBer, Training Resources Group.

Boyatzis, R. E., & Kolb, D. A. (1995, March/April). From learning styles to learning skills: The executive skills profile. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 10(5), 3–17.

Boyatzis, R. E., & Kolb, D. A. (1997). Assessing individuality in learning: The Learning Skills Profile. Educational Psychology, 11(3–4), 279–295.

Burns, J. M. (1978). Leadership. New York: Harper & Row.

Eubank, D., Geffken, D., Orzano, J., & Ricci, R. (2012). Teaching adaptive leadership to family medicine residents: What? Why? How? Families Systems & Health, 30(3), 241–252.

Fink, L. (2012, September). Leading in the 21st century: An interview with Larry Fink, chairman and CEO, BlackRock. McKinsey Quarterly: The Online Journal of McKinsey & Company, 1–6.

Goleman, D. (1995). Emotional intelligence: Why it can matter more than IQ. New York: Bantam Books.

Heifetz, R. A., & Laurie, D. L. (1997, January/February). The work of leadership. Harvard Business Review, pp. 124–134.

Heifetz, R. A., Linsky, M., & Grashow, A. (2009). The practice of adaptive leadership: Tools and tactics for changing your organization and the world. Boston, MA: Harvard Business Press.

Kolb, A. Y., & Kolb, D. A. (2005a). Learning styles and learning spaces: Enhancing experiential learning in higher education. Academy of Management Learning and Education, 4(2), 193–212.

Kolb, A. Y., & Kolb, D. A. (2005b). The Kolb Learning Style Inventory version 3.1: 2005 Technical Specifications. Boston, MA: Hay Resources Direct.

Kolb, A. Y., & Kolb, D. A. (2006). A review of multidisciplinary application of experiential learning theory in higher education. In R. Sims & S. Sims (Eds.), Learning styles and learning: A key to meeting the accountability demands in education. Hauppauge, NY: Nova Publishers.

Kolb, A. Y., & Kolb, D. A. (2009). Experiential learning theory: A dynamic, holistic approach to management learning, education and development. In S. J. Armstrong & C. Fukami (Eds.), Handbook of management learning, education and development. London: Sage Publications.

Kolb, A. Y., & Kolb, D. A. (2011). Learning Style Inventory version 4.0. Boston, MA: Hay Resources Direct. www.learningfromexperience.com

Kolb, D. A. (1971). Individual learning styles and the learning process. Working Paper 535–71, Sloan School of Management, Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Kolb, D. A. (1984). Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Kolb, D. A., Lublin, S., Spoth, J., & Baker, R. (1986). Strategic management development: Using experiential learning theory to assess and develop managerial competence, The Journal of Management Development, 5(3), 13–24.

Kolb, D. A., & Yeganeh, B. (in press). Deliberate experiential learning: Mastering the art of learning from experience. In K. Elsbach, C. D. Kayes, & A. Kayes (Eds.), Contemporary organizational behavior in action. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education.

Kotter, J. P. (1990). A force for change: How leadership differs from management. New York: The Free Press.

Leonard, G. (1992). Mastery: The keys to success and long-term fulfillment. New York: Plume.

Montgomery, C. (2012, July). How strategists lead. McKinsey Quarterly: The Online Journal of McKinsey & Company, 2–7.

Peres, S. (2012, September). Leading in the 21st century: An interview with Shimon Peres, President of Israel. McKinsey Quarterly: The Online Journal of McKinsey & Company, 1–4.

Rainey (Sharp), M. A. (1991). Career development in academic family medicine: An experiential learning approach. Unpublished Ph.D. dissertation, Case Western Reserve University.

Rainey, M. A., Hekelman, F., Galazka, S.F., & Kolb, D. A. (1993, February). Job demands and personal skills in family medicine: Implications for faculty development. Family Medicine, 25, 100–103.

Rainey, M. A., & Kolb, D. A. (1995). Using experiential learning theory and learning styles in diversity education. In R. R. Sims & S. J. Sims (Eds.), The importance of learning styles: Understanding the implications for learning, course design and education (pp. 129–46). Westport, CT: Greenwood Press.

Seijts, G. H., & Latham, G. P. (2005). Learning versus performing goals: When should each be used? Academy of Management Executive, (19), 124–131.

Senge, P. (1990). The fifth discipline: The art and practice of the learning organization. New York: Currency/Doubleday.

Smith, D. (1990). Physician managerial skills: Assessing the critical competencies of the physician executive. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. Department of Organizational Behavior, Weatherhead School of Management, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, Ohio.

Wren, D. A. (1987). The evolution of management thought (3rd ed.). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Zaleznik, A. (1977, May/June). Managers and leaders: Are they different? Harvard Business Review, 55, 67–78.