4. The Anatomy of a Class

In previous chapters we have covered the fundamental object-oriented (OO) concepts and determined the difference between the interface and the implementation. No matter how well you think out the problem of what should be part of the interface and what should be part of the implementation, the bottom line always comes down to how useful the class is and how it interacts with other classes. A class should never be designed in a vacuum, for as might be said, no class is an island. When objects are instantiated, they almost always interact with other objects. An object can also be part of another object or be part of an inheritance hierarchy.

This chapter examines a simple class and then takes it apart piece by piece along with guidelines that you should consider when designing classes. We will continue using the cabbie example presented in Chapter 2, “How to Think in Terms of Objects.”

Each of the following sections covers a particular aspect of a class. Although not all components are necessary in every class, it is important to understand how a class is designed and constructed.

note

This example class is meant for illustration purposes only. Some of the methods are not fleshed out (meaning that there is no implementation) and simply present the interface—primarily to emphasize that the interface is the focus of the initial design.

The Name of the Class

The name of the class is important for several reasons. The obvious reason is to identify the class itself. Beyond simple identification, the name must be descriptive. The choice of a name is important because it provides information about what the class does and how it interacts within larger systems.

The name is also important when considering language constraints. For example, in Java, the public class name must be the same as the filename. If these names do not match, the application won’t compile.

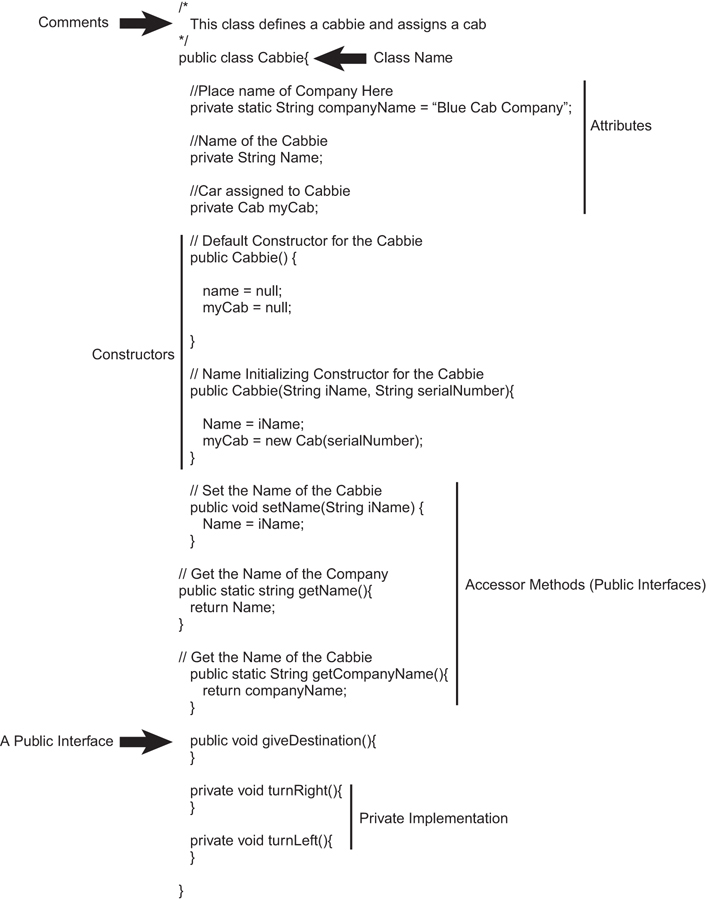

Figure 4.1 shows the class that will be examined. Plain and simple, the name of the class in our example, Cabbie, is the name located after the keyword class:

public class Cabbie {

}

Using Java Syntax

Remember that the convention for this book is to use Java syntax. The syntax will be similar but, perhaps, somewhat different in other languages.

The class Cabbie name is used whenever this class is instantiated.

Comments

Regardless of the syntax of the comments used, they are vital to understanding the function of a class. In Java and other languages, two kinds of comments are common.

The Extra Java and C# Comment Style

In Java and C#, there are three types of comments. In Java, the third comment type (/** */) relates to a form of documentation that Java provides. We do not cover this type of comment in this book. In C#, the syntax to create documentation comments is ///, much like the /** */ Javadoc documentation comments.

The first comment is the old C-style comment, which uses/* (slash-asterisk) to open the comment and */ (asterisk-slash) to close the comment. This type of comment can span more than one line, and it’s important not to forget to use the pair of open and close comment symbols for each comment. If you miss the closing comment (*/), some of your code might be tagged as a comment and ignored by the compiler. Here is an example of this type of comment used with the Cabbie class:

/* This class defines a cabbie and assigns a cab */

The second type of comment is the // (slash-slash), which renders everything after it, to the end of the line, a comment. This type of comment spans only one line, so you don’t need to remember to use a close comment symbol, but you do need to remember to confine the comment to just one line and not include any live code after the comment. Here is an example of this type of comment used with the Cabbie class:

// Name of the cabbie

Attributes

Attributes represent the state of the object because they store the information about the object. For our example, the Cabbie class has attributes that store the name of the company, the name of the cabbie, and the cab assigned to the cabbie. For example, the first attribute stores the name of the company:

private static String companyName = "Blue Cab Company";

Note here the two keywords private and static. The keyword private signifies that a method or variable can be accessed only within the declaring object.

Hiding as Much Data as Possible

All the attributes in this example are private. This is in keeping with the design principle of keeping the interface design as minimal as possible. The only way to access these attributes is through the method interfaces provided (which we explore later in this chapter).

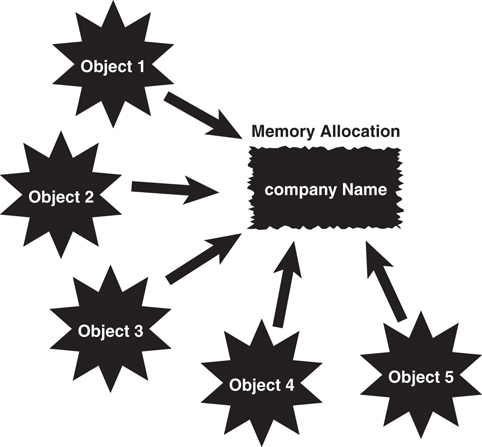

The static keyword signifies that there will be only one copy of this attribute for all the objects instantiated by this class. Basically, this is a class attribute. (See Chapter 3, “More Object-Oriented Concepts,” for further discussion on class attributes.) Thus, even if 500 objects are instantiated from the Cabbie class, only one copy will be in memory of the companyName attribute (see Figure 4.2).

The second attribute, name, is a string that stores the name of the cabbie:

private String name;

This attribute is also private so that other objects cannot access it directly. They must use the interface methods.

The myCab attribute is a reference to another object. The class, called Cab, holds information about the cab, such as its serial number and maintenance records:

private Cab myCab;

Passing a Reference

It is likely that the Cab object was created by another object. Thus, the object reference would be passed to the Cabbie object. However, for the sake of this example, the Cab is created within the Cabbie object. As a result, we are not really interested in the internals of the Cab object.

Note that at this point, only a reference to a Cab object is created; there is no memory allocated by this definition.

Constructors

This Cabbie class contains two constructors. We know they are constructors because they have the same name as the class: Cabbie. The first constructor is the default constructor:

public Cabbie() {

name = null;

myCab = null;

}

Technically, this is not a default constructor provided by the system. Recall that the compiler will provide an empty default constructor if you do not code any constructor for a class. By definition, the reason it is called a default constructor here is because it is a constructor with no arguments, which, in effect, overrides the compiler’s default constructor.

If you provide a constructor with arguments, the system will not provide a default constructor. Although this can seem complicated, the rule is that the compiler’s default constructor is included only if you provide no constructors in your code.

No Constructor

Coding no constructor and allowing the default constructor to be in play can cause maintenance headaches down the road. If the code relies on a default constructor, and another constructor is added later, the default constructor will not be included by the system.

In this constructor, the attributes name and myCab are set to null:

name = null; myCab = null;

The Nothingness of Null

In many programming languages, the value null represents a value of nothing. This might seem like an esoteric concept, but setting an attribute to nothing is a useful programming tech-nique. Checking a variable for null can identify whether a value has been properly initialized. For example, you might want to declare an attribute that will later require user input. Thus, you can initialize the attribute to null before the user is given the opportunity to enter the data. By setting the attribute to null (which is a valid condition), you can check whether an attribute has been properly set. Note that in some languages this is not allowed with the string type. In .NET for example, it is required to use name = string.empty;.

As we know, it is always a good coding practice to initialize attributes in the constructors. In the same vein, it’s a good programming practice to then test the value of an attribute to see whether it is null. This can save you a lot of headaches later if the attribute or object was not set properly. For example, if you use the myCab reference before a real object is assigned to it, you will most likely have a problem. If you set the myCab reference to null in the constructor, you can later check to see whether myCab is still null when you attempt to use it. An exception might be generated if you treat an uninitialized reference as if it were properly initialized.

Consider another example: If you have an Employee class that includes a spouse attribute (perhaps for insurance purposes), you’d better make provisions for the situation when an employee is not married. By initially setting the attribute to null, you can then check for this status.

The second constructor provides a way for the user of the class to initialize the Name and myCab attributes:

public Cabbie(String iName, String serialNumber) {

name = iName;

myCab = new Cab(serialNumber);

}

In this case, the user would provide two strings in the parameter list of the constructor to properly initialize attributes. Notice that the myCab object is instantiated in this constructor:

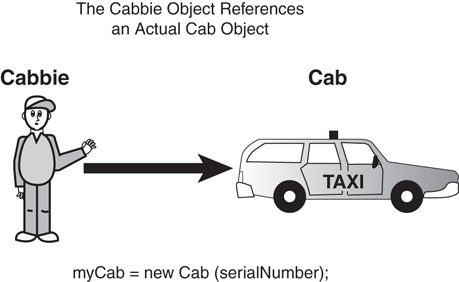

myCab = new Cab(serialNumber);

As a result of executing this line of code, the storage for a Cab object is allocated. Figure 4.3 illustrates how a new instance of a Cab object is referenced by the attribute myCab. Using two constructors in this example demonstrates a common use of method overloading. Notice that the constructors are all defined as public. This makes sense because in this case, the constructors are obvious members of the class interface. If the constructors were private, other objects couldn’t access them—thus, other objects could not instantiate a Cab object.

Cabbie object referencing a cab object.Multiple Constructors

It's worth noting that it is sometimes considered a less than ideal practice to use more than one constructor nowadays. With the prevalence of Inversion of Control (IoC) containers and the like, it's frowned upon, and even unsupported, for a number of frameworks without special configuration.

Accessors

In most, if not all, examples in this book, the attributes are defined as private so that any other objects cannot access the attributes directly. It would be ridiculous to create an object in isolation that does not interact with other objects—for we want to share appropriate information. That said, isn’t it sometimes necessary to inspect and, perhaps, change another class’s attribute? The answer is, of course, yes. There are many times when an object needs to access another object’s attributes; however, it does not need to do it directly.

A class should be very protective of its attributes. For example, you do not want object A to have the capability to inspect or change the attributes of object B without object B having control. There are several reasons for this; the most important reasons boil down to data integrity and efficient debugging.

Assume that a bug exists in the Cab class. You have tracked the problem to the Name attribute. Somehow it is getting overwritten, and garbage is turning up in some name queries. If Name were public and any class could change it, you would have to go searching through all the possible code, trying to find places that reference and change Name. However, if you let only a Cabbie object change Name, you’d have to look only in a method of the Cabbie class. This access is provided by a type of method called an accessor. Sometimes accessors are referred to as getters and setters, and sometimes they’re simply called get() and set(). By convention, in this book we name the methods with the set and get prefixes, as in the following:

// Set the Name of the Cabbie

public void setName(String iName) {

name = iName;

}

// Get the Name of the Cabbie

public String getName() {

return name;

}

In this code snippet, a Supervisor object must ask the Cabbie object to return its name (see Figure 4.4). The important point here is that the Supervisor object can’t retrieve the information on its own; it must ask the Cabbie object for the information. This concept is important at many levels. For example, you might have a setAge() method that checks to see whether the age entered was 0 or below. If the age is less than 0, the setAge() method can refuse to set this obviously incorrect value. In general, the setters are used to ensure a level of data integrity.

This is also an issue of security. You may have sensitive data, such as passwords or payroll information, that you want to control access to. Thus, accessing data via getters and setters provides the capability to use mechanisms like password checks and other validation techniques. This greatly increases the integrity of the data.

Objects

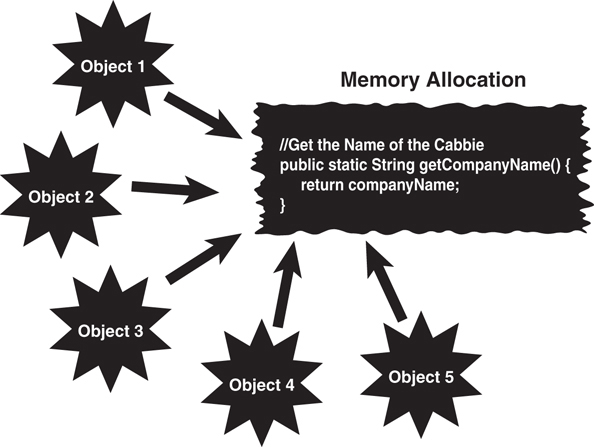

Actually, there isn't a physical copy of each nonstatic method for each object. Each object would point to the same physical code. However, from a conceptual level, you can think of objects as being wholly independent and having their own attributes and methods.

The following code fragment illustrates how to define a static method, and Figure 4.5 shows how more than one object points to the same code.

Static Attributes

If an attribute is static, and the class provides a setter for that attribute, any object that invokes the setter will change the single copy. Thus, the value for the attribute will change for all objects.

// Get the Name of the Cabbie

public static String getCompanyName() {

return companyName;

}

Notice that the getCompanyName method is declared as static, as a class method; class methods are described in more detail in Chapter 3. Remember that the attribute companyName is also declared as static. A method, like an attribute, can be declared static to indicate that there is only one copy of the method for the entire class.

Public Interface Methods

Both the constructors and the accessor methods are declared as public and are part of the public interface. They are singled out because of their specific importance to the construction of the class. However, much of the real work is provided in other methods. As mentioned in Chapter 2, the public interface methods tend to be very abstract, and the implementation tends to be more concrete. For this class, we provide a method called giveDestination that is the public interface for the user to describe where she wants to go:

public void giveDestination(){

}

What is inside this method is not important at this time. The main point is that this is a public method, and it is part of the public interface to the class.

Private Implementation Methods

Although all the methods discussed so far in this chapter are defined as public, not all the methods in a class are part of the public interface. It is common for methods in a class to be hidden from other classes. These methods are declared as private:

private void turnRight(){

}

private void turnLeft() {

}

These private methods are meant to be part of the implementation and not the public interface. You might ask who invokes these methods, if no other class can. The answer is simple: You might have already surmised that these methods are called internally from the class itself. For example, these methods could be called from within the method giveDestination:

public void giveDestination(){

.. some code

turnRight();

turnLeft();

.. some more code

}

As another example, you may have an internal method that provides encryption that you will use only from within the class itself. In short, this encryption method can’t be called from outside the instantiated object itself.

The point here is that private methods are strictly part of the implementation and are not accessible by other classes.

Conclusion

In this chapter we have gotten inside a class and described the fundamental concepts necessary for understanding how a class is built. Although this chapter takes a practical approach to discussing classes, Chapter 5, “Class Design Guidelines,” covers the class from a general design perspective.

References

Fowler, Martin. 2003. UML Distilled, Third Edition. Boston, MA: Addison-Wesley Professional.

Gilbert, Stephen, and Bill McCarty. 1998. Object-Oriented Design in Java. Berkeley, CA: The Waite Group Press.

Tyma, Paul, Gabriel Torok, and Troy Downing. 1996. Java Primer Plus. Berkeley, CA: The Waite Group.