The Changed Business Landscape

How It Was

If one of today’s graduates was taken back in time to the corporate office of the early 1980s, they would notice a few differences. Staff smoked at their desk, and there was no need for offering to make the tea etiquette as tea ladies brought mid-morning refreshments around. It was a strict nine to five culture, with the office deserted within 10 minutes of 5 p.m. Sending a memo involved having it typed by a secretary, of which there were many, along with other admin staff. This level of resource was necessary because there were few computers and they were mainframes, off in a distant site somewhere. The new graduate might also be struck by who else was around. Many people worked for the same company all their careers, and they largely felt secure in their jobs. One of the authors remembers his first graduate job at an engineering company in a diversified conglomerate. One of the people he was introduced to was Dan, comfortable at his desk by the window that he seemed to look out most of his day. Dan had been with the company for as long as anyone remembered. When he asked what Dan did, he was told he looked after the s300 range. When he asked whether they still made the s300 range, he was told no, but “there are still quite a few out there and we sometimes get people calling up asking how to calibrate them, or for parts.”

The lack of technology would perhaps be the first thing our time-traveling graduate would notice, but, after reflection, they may think that the most profound is that there are no Dans anymore.

In the distant days of the 1980s, people were in the office for 40 hours and had jobs they could comfortably get done in 40 hours. There was also plenty of people making their way on the management track being moved around from line jobs to overseas posts and back again to head office jobs. And often, they were between roles and available to run a project, maybe introduce one of those new whizzy computer systems, for instance.

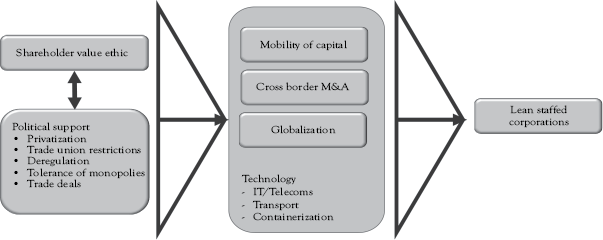

It was a comfortable world of short commutes to 40-hour weeks for 40 years, leading to a pension of forty-sixtieths of your final salary. It is a different world now, why did it change? Figure 3.1 lays out the process.

Figure 3.1 Drivers of business change

Drivers of Change

The 1980s saw the emergence of several drivers that changed the culture and conditions of the corporate office.

New Business and Political Ethic

Corporations have always been keen on profit of course, but this was seen in a context of a wider societal role. During the 1980s, a new ethic arose in the business schools and board rooms, the ethic of shareholder value. It became to be seen that the only fiduciary duty of the board was to add value for shareholders. At the political level, this was seen as socially desirable because by pursuing this objective, the business would flourish, leading to more wealth to the benefit of society at large.

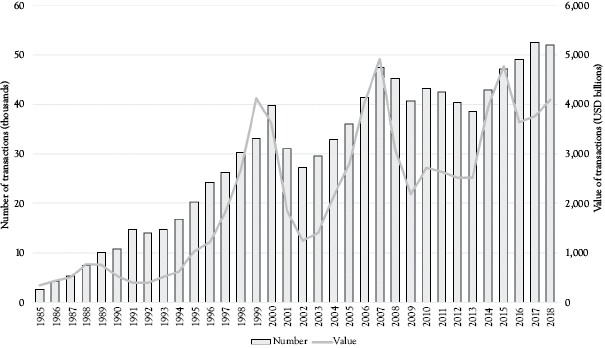

This ethic was supported by government in many ways, including privatizing nationalized industries and eliminating trade union power, but, possibly, most importantly, in the form of financial deregulation and by taking a permissive attitude to corporate takeovers. In the United States, the antitrust policy and enforcement declined due to the Reagan administration’s enforcement priorities, judicial appointments, and submissions to the Supreme Court. In the United Kingdom, the body responsible for making sure companies did not acquire monopoly power, the Monopolies and Mergers Commission symbolically even dropped reference to monopoly and rebranded as the Competition Commission. Corporations are driven to merge and takeover competitors to increase competitiveness, via economies of scale, and increase profits and power by sheer size. The combination of more potential targets and lots of new deregulated banking money led to a large increase in corporate takeover activity (see the preceding chart in Figure 3.2). Increased mergers and acquisitions (M&As) meant that corporate executives not only faced competitive pressure for their products, but also pressure over ownership of their companies. They needed to make their companies fit enough to fight off hostile takeovers or to engage in hostile takeovers.

Figure 3.2 Announced mergers and acquisitions worldwide

Source: IMAA Institute, https://imaa-institute.org/mergers-and-acquisitions-statistics/

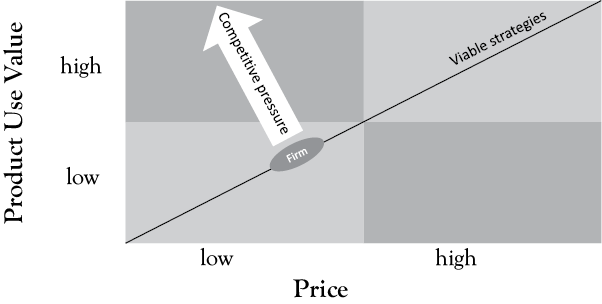

Business competes by providing products and services. Figure 3.3 is the customer matrix showing the market from the customer’s perspective. The diagonal line shows viable competitive strategies in the market. Bottom left sell cheap and cheerful and a low price; top right sell premium high quality for a premium price. But wherever a company is on the line, over time, customers will always be looking for better products at lower prices. Competitors will be trying to provide them. It is a cliché because it is true: a business must run just to stay still. The pressure is to move the viable strategy line up and left. How is that done?

Figure 3.3 Customer matrix

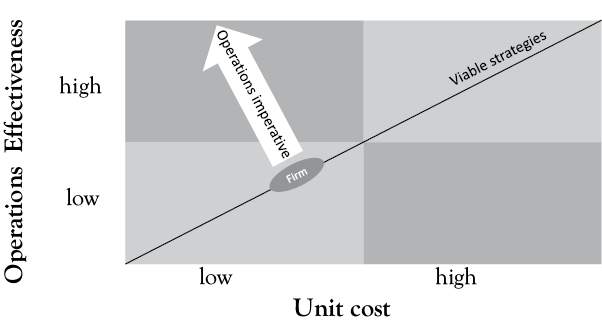

What does running look like? A business cannot act directly on the consumer matrix; instead, it must act on the producer matrix, see Figure 3.4. It shows the competitive world from the perspective of businesses. To provide products and services with more use value, it must be more effective, that is, provide things that customers value. The price a business can charge is dictated by the unit costs of providing the product or service. In other words, being more efficient allows the business to offer lower prices or make more profit at the same price. To move on the consumer matrix, the business must move on the producer matrix up and left. The pressure is for ever-more efficiency. Add value by doing the same with lower costs.

Figure 3.4 Producer matrix

For many businesses, a major cost is people, and so, the major pressure has been to add shareholder value by reducing the size of the workforce.

Globalization

Globalization is the trend of increasing interaction and trade between people and companies on a worldwide scale. It is another major trend and supported by political developments.

The first is the growth of global trading blocs such as the European Union, North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), and Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN). Within these blocks, there is frictionless trading across national borders because of common regulations and zero tariffs.

The World Trade Organization was formed in 1995. It establishes frameworks for international trade, facilitating trade deals between countries and trading blocs, resulting in reduced tariff and other barriers.

Financial deregulation, mentioned earlier, has meant a general reduction in legal barriers to the movement of capital, making it easier for capital to flow between different economies. This means firms can finance expansion into foreign markets and engineer profits to be made in low tax jurisdictions.

There has been increased mobility of labor. Although still a small percentage of the global population, according to UN1 Migration Reports, in 2017, 258 million people lived outside their countries of origin, up by 100 million since 1990. It is not always optimal for corporations to site assets in countries with the lowest cost labor. Sometimes, it is best to import the labor to existing assets. This might be cheap labor to pick peaches in South Carolina or pick Amazon orders in warehouses in Texas, or it might be the highly educated for tech companies in Silicon Valley. Corporations have wanted it, so governments have facilitated widespread immigration. Given this pull from corporations in the West, citizens of developing countries have responded to the chance to improve their economic prospects. The unskilled, but also the educated. Graduates from eastern Europe become porters in London; India and China produce millions of English-speaking graduates every year able to work anywhere. Global media and social media present the lifestyles and opportunities in the West around the world, making these faraway places less strange and scary. Financial deregulation means overseas workers can remit pay back home, and these flows now play a large role in transfers from developed countries to developing countries. There are also significant push factors in the form of destabilization of large parts of the world. The international drugs war has created social dislocation due to cartel-related lawlessness and violence. Regime change polices in the Middle East have been prosecuted with real wars in Libya, Syria, Iraq, Yemen, and Afghanistan and lethal drone strikes beyond the war zones. There are strict trade sanctions on a further list of countries in three continents. These polices have forced people to flee economic collapse and a real threat of injury and death.

Technology

Underlying the aforementioned trends are technological advances. They have supported and enabled business consolidation and globalization.

From the early 1970s, containerization dramatically reduced the costs of moving freight between rail, ship, and road. This made international trade cheaper and more efficient.

Improved transport made global travel easier. Low-cost air-travel has led to rapid growth, enabling greater movement of people and goods across the globe.

But, the biggest impact has been the dramatic development of telecoms and information technology (IT). It is now easy to communicate and share information around the world. To exploit the technology advances, there are business schools turning out MBA consultants to provide approaches and techniques including business process reengineering; outsourcing; Six Sigma; just in time; lean manufacturing; and total quality management.

This communication technology and other globalization enablers have freed corporations to reconfigure operations to the lowest-cost workforce or to jurisdictions with the weakest regulation or lowest taxes. It has also made it possible for corporations to grow much bigger and maintain control over its sprawling assets with ever fewer management staff.

Some Consequences

Industry concentration is a measure of the market share of the top few companies. A 2016 paper2 concluded more than 75 percent of U.S. industries have experienced an increase in the concentration levels over the last two decades. Firms in industries with the largest increases in product market concentration have enjoyed higher profit margins,

positive abnormal stock returns, and more profitable mergers and acquisition deals, suggesting that market power is an important source of profit. Let us take Canada as an example3 for trends everywhere. In 1950, an average firm within the top 60 was five times as large as an average of all firms listed on the Toronto Stock Exchange. By 1990, that ratio had risen only a little from five to six. By 2012, the ratio was 23. This pattern is reflected at the global level. In most mature industries, half a dozen or less companies dominate and control the market worldwide.4 In mining, Glencore Xstrata has a revenue of 200 billion U.S. dollars, then comes ArcelorMittal at 70 billion U.S. dollars, and by Rio Tinto and BHP Billiton they are down to 40 billion U.S. dollars. There are just two domestic consumer goods suppliers, P&G and Lever. Looking at the U.S. market: baby food, three companies, Abbott, Mead Johnson, and Nestlé, have 80 percent of the market; footwear, Nike has 30 percent share, the next less than six percent; tobacco, two companies with 83 percent share, and Reynolds just announced a merger with U.K. giant BAT; dishwashers, three companies with 65 percent share. Even relatively new industries are the same such as mobile phones with four companies dominating worldwide.

Flatter Organizational Structures

The Wall Street Journal ran an article on PepsiCo5 Inc.’s Gemesa cookie business in Mexico. In the 1990s, the company ran with 12 employees per manager. In 2008, its factories operated with 56 employees per manager. They noted the changes have helped Gemesa improve its business results. That may be extreme, but another article analyzing S&P 500 company performance reported Sung Won Sohn, a former chief economist at Wells Fargo as saying “U.S. companies became leaner, meaner and hungrier.” In 2007, S&P companies generated an average of 378,000 U.S. dollars in revenue for every employee. In 2016, that figure had risen 20 percent to 510,000 U.S. dollars.

Longer Working Weeks for Some

A 2015 London School of Economics (LSE) study into working hours6 identified that in western European countries, the frequency of individuals working extreme hours has increased substantially, particularly among high-skilled male workers. The study points to the effects of globalization and to national labor regulations and welfare reforms. Of course, extreme working hours have health impacts, and in recognition of this, in 2019, the World Health Organization (WHO) added burn-out to the International Classification of Diseases.7

So How Is It Today?

These trends have impacted different industries at different rates and times. Manufacturing first, service industries later, and finally, public sector and charities. Universities are now less concerned with creating prepared minds and more with courses as profit centers, targeting market segments, making pricing decisions based on demand to maximize profit contribution.

The outcome is a concentration of business in fewer corporations and the concentration of work into fewer individuals. Corporations have consolidated into fewer giant multinational companies with a global presence in many different national economies. They have continually stripped out layers of management and non-core functions, and at the same time, provided some functions from global service centers rather than locally.

For the general population, wages and working hours have stagnated;8 for professionals in corporations, there has been a growth of extreme working hours. Fewer professionals and managers with more responsibilities are working longer hours. Corporations have cut the workforce to the extent that everyone left is busy all the time, leaving no spare staff capacity.

So, how is it in today’s corporate working environment compared to the 1980s? Change is constant. Organizational structures are flat and management teams are lean. Expectations for results are higher and timeframes are shorter. Senior managers spend less time in post, so they need to make their mark faster. Client contracts are shorter and pressure on prices greater. Decision-making time is shorter and projects need to happen faster. Service problems reach the media instantaneously, risking personal and business reputations.

Staff no longer smoke at their desk, they make their own tea, nine to five culture has been replaced by 24-hour availability, communication is instant and easy to send but often overwhelming to receive, the typing pool and admin staff are now a smartphone and a computer you take everywhere with you, and there are no Dans anymore. There are no managers between roles to run projects. It is a world of long commutes to 60-hour weeks, engaging in multiple careers in multiple companies without final salary pensions.

1 International Migration Reports, 2013 and 2017. United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs

2 Are US Industries Becoming More Concentrated? Gustavo Grullon, Yelena Larkin, and Roni Michaely October 2016.

3 A Shrinking Universe: How Concentrated Corporate Power is Shaping Income Inequality in Canada. Jordan Brennan. November 2012.

4 Euromonitor.

5 Overseeing More Employees With Fewer Managers. Consultants Are Urging Companies to Loosen Their Supervising Views, By George Anders. Updated March 24, 2008, 12:01 a.m. ET.

6 Extreme Working Hours in Western Europe and North America: A New Aspect of Polarization. Anna S. Burger. LSE, May 2015.

7 World Health Organization, May 2019 => https://who.int/mental_health/evidence/burn-out/en/

8 Pew Research https://pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2018/08/07/for-most-us-workers-real-wages-have-barely-budged-for-decades/