Impact and the People Project Triangle

We have seen that the pace of business change has risen; this means the pace with which businesses need to respond with new and reconfigured assets and processes has risen. This is done with projects, so the need for more projects to deliver ever more quickly, effectively, and efficiently.

Fortunately, in response to this need, the project management discipline has professionalized. We now have well-researched and tried methods, tools, and techniques that increase the chance of project success.

Undermining this progress though is the continual competition for resources between projects and business as usual (BaU). This is true for all projects, but it is especially true for composite projects—those staffed with in-house people working on them part time. The result is ever-increasing pressure on those in-house staff.

Why is this important when everyone works under pressure and has too much to do? The key issue is composite project structures are a valuable way to run projects, but they should not happen by accident. Organizations using composite projects and unaware of the implications of these structures are exposed to unrecognized risks and unexpected problems. Organizations should be explicitly aware they are organizing a composite project structure and understand the implications of the decision. Then, they will be prepared to overcome some of the practical and organizational hurdles.

The seeds of problems are likely in place even before the appointment of a project manager, when the first-time project sponsor and business lead initiate the project as a supplement to their primary role. Right from the start, they are working outside their normal schedule. They are likely to be working at capacity and have to do extra hours, so will regard it as homework. It is then they create a composite project without realizing it, and without understanding the implications and the risks they are taking on. Risks that can be serious, for the organization and for the reputations of participants.

So, what are the implications? Project managers often use the project triangle concept to understand trade-offs and limitations of resourcing decisions between quality, time, cost, and scope. In composite projects, there is a higher level of trade-off between the people working on the project, the ongoing operations of the business, and the project itself. The next sections build on this concept to establish a clear understanding of why composite projects are different and what the implications are.

The Project Triangle

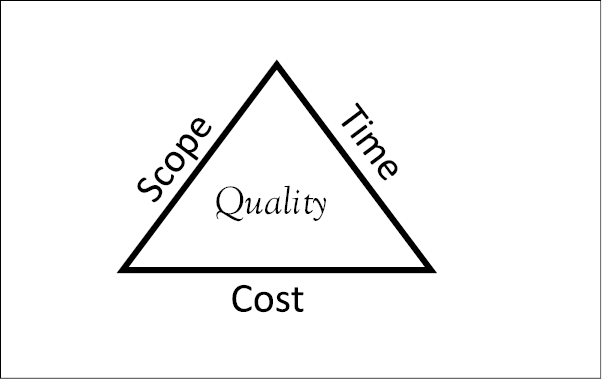

The project triangle or iron triangle, see Figure 5.1, is a tool that has been used by project managers for a long time, if not well known outside the discipline. It is used to describe the balance and trade-offs between constraints and risks.

Figure 5.1 The project triangle

The triangle shows the relationship between scope, time, and cost. The fourth variable, quality, anchors the others together. The key concept is that you cannot improve all the variables at once. Like a law of physics, at least one variable must give. For example, to deliver a project in less time, you must either reduce the scope, increase the cost, or both.

When managing a project, it is important to understand on which of the variables your project is focused and which can be compromised. Sometimes, it is obvious; many times, it is not. For example, if you are Boeing and the U.S. Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) has grounded one of your aircraft models until a safety upgrade is completed, the project is going to be focused on scope (fit the upgrade on all aircraft) and time (get it done as soon as possible). Cost will be the variable that is flexible because of the huge damage being done to the company while the aircraft are grounded.

For new software products, often, the launch date is important. This might be due to external factors like a product to meet the arrival of a new regulation or a game to hit the Christmas peak. It might be due to internal factors like meeting the expectations created by pre-launch publicity and marketing. In this case, time is the focus. However, cost may also be constrained, as there are diminishing returns on adding resources. So, the scope is likely to be the flexible variable with non-essential features pushed back into later releases.

As it is usually the last to be compromised, quality sits in the middle. You might reduce the number of deliverables (scope) in a project, but those left must work properly. Using a fanciful example, the intention might be to make a prestige five door car. If you run out of cash, you can still build a prestige three door car. However, there are times quality might be traded. For a building development, lower-cost heat insulation materials might be traded for higher utility bills during operation. Lower-quality fittings might be traded for shorter life and hence, higher lifetime costs.

This is a valuable framework, but business is about getting more from less. Determined and ambitious managers will always demand more features, more speed, and less cash. There is another law of nature that should be explicitly considered. There is a relationship between more risk and more reward.

As a hypothetical example, an organization wants to restructure its customer service operation that includes a management team and a call center. The project has been set up as follows:

- • Scope is facilities and new job descriptions for 50 people, all posts subject to change, one location.

- • Time is 3 months from announcement to new structure. Budget includes redeployment costs and a small amount of specialist external resource.

- • The project is sponsored by the chief executive, but will be delivered by the human resources (HR) team, with support from operational managers.

On the face of it, the project is well planned. However, the chief executive becomes uncomfortable on the lead up to the announcement and, for sound reasons, feels that the time to launch is too long and will be very unsettling for the customer service team, and pose a risk to the operation. The project is now to be completed in two months.

So, considering the project triangle, what are the options?

- • Reduce the scope by decreasing the number of people affected. This will reduce the amount of communication required and the face-to-face sessions with staff.

- • Increase the cost by increasing the resources from HR available to the project. This might be by using overtime or buying in additional resources to support the HR team.

There is a third option:

- • Reduce the time, make no changes to scope and cost, but increase risk.

The risks that you would identify for this project would be:

- • Industrial relations issues reducing operational performance.

- • Legal action resulting in legal costs.

- • Overworked HR team, resulting in sickness or staff turnover.

- • Operations managers lose focus, resulting in lower operational performance.

In practice, the option to reduce scope is unlikely to be feasible because a partial restructure is unlikely to deliver the business case. This leaves the option to increase spend or accept the risks shown earlier. It is a legitimate practice for a business to accept risks—it is an option in the PRINCE2 manual: providing it is done consciously and explicitly. Too frequently, blindly taking on risks like these typically just delays the inevitable. Antagonizing the team and overworking the HR department often incurs higher costs eventually, and maybe even higher costs than before.

Faced with challenges to scope, time, and cost, it is possible to use the project triangle along with an analysis of risk, as a tool to explicitly guide thinking.

Trade-offs and risk around composite projects are key themes of this book. In the rest of this chapter, we will add to your understanding of the composite project environment by building on this concept of the project triangle.

The Composite Project Environment

For project managers not used to composite project environments, the experience can be very frustrating. Much of this is organization culture mismatch. The demands and culture of a project-orientated department, such as IT, differ radically from the nature of operations or BaU. We introduced this in Part I, and the key differences are repeated in Table 5.1:

Table 5.1 Projects and BaU compared

|

Feature |

BaU management |

Project management |

|

Responsibility |

For status quo |

For change |

|

Authority |

Defined by organizational structure |

Fuzzy |

|

Tasks |

Consistent |

Ever-changing |

|

Stability |

Permanent |

Temporary |

|

Focus |

Efficiency |

Conflict resolution and tradeoffs |

Construction and IT projects tend to be more directly sequence-restricted; things must be done in a specific sequence. The concrete must set before the roof trusses can be put up. It does not matter how many people you throw at the task, the fact that concrete must set will not change. In the BaU world of service operations, for example, there is usually more flexibility over the order tasks that can be carried out, and often the option of all hands on-deck to solve a problem.

It is not surprising that when project-orientated people are mixed with BaU-orientated people, there is often misunderstanding and conflict. The two groups do not understand each other. As a project manager in a composite environment, it is essential you understand your BaU colleagues if you are to get the most out of them.

There are two broad categories of difference: cultural and practical.

Cultural

Organizations thrive because of the benefits of specialization of function. Staff in different disciplines have different skills and aptitudes and, of course, attitudes. Project specialists work in a way that is different to operations, marketing, or finance. In particular, departments with a never-ending, consistent output are orientated to stability over change; consistent repeat actions over unique tasks; and efficiency over innovation and trade-offs. An important cultural difference is that in BaU, being a safe pair of hands and not making mistakes is highly valued. This works against the need for innovation and flexibility that is needed and prized in projects.

For example, compared to project-oriented staff, operational staff:

- • May be very impatient in meetings and want things to be done quickly, leading them to rush to solutions before the problem is fully assessed.

- • May dismiss up-front thinking and planning as just delay and procrastination and so regard detail in project documents, like the requirements specification, as a waste of time.

- • Think the project is going too slowly, that things could be done much quicker by avoiding the project bureaucracy.

- • May have been volunteered for the role in the project because they have the specialist subject knowledge, but have no interest in delivery.

- • May not understand project methodology and approaches and find it difficult to relate to them.

Practical

A project manager must realize that part-time operations staff on a project have a full-time job, against which they have performance targets and goals. Targets and goals they will be measured against come their annual review. Their time is limited, and their future is linked to their line manager not the project manager. This means operational issues will be prioritized over the part-time temporary project.

- • If a customer or other operational emergency emerges, then staff probably will not appear at the requirements workshops or project meetings.

- • There will be financial or operational or seasonal peak periods during the week, month, or year, which may mean you have to build the plan around them. Failure to do so will mean the BaU staff will not be available to the project.

- • It is likely that the staff will have little time assigned to the project and so forced to schedule project work into an already busy week. It is common for them to think of their normal work responsibilities as the day job, and project work, perceived as outside normal responsibilities that they must do in addition, as homework. They might refer to their regular job as real work.

- • Line managers may resent the time their staff are spending on the project.

Project management from traditional project environments such engineering and IT:

- • May unreasonably expect project staff to understand project methodology and tools.

- • Fail to tailor the project methodology to suit the composite structure and insist on strictly following the processes with unnecessary meetings and reports.

- • Issue work packages that are too big or complex for the part-time staff to manage.

- • Be frustrated by lack of direct line control over part-time staff and hence, attendance or late deliverables.

- • Have experience dominated by repeater-type projects, which are projects like the last job, but with specific differences. For example, a building contractor has managed many housing developments in the past. All the main elements are well known and been done before, but the specifics must be managed, such as particular ground requirements, or particular suppliers. Business projects tend to be highly bespoke projects that are unique for the organization, such as create a new service, a relocation, a reorganization, or process change. These tend to have more uncertainty, but rigid deadlines.

Time and Mental Capacity

Another key issue for the composite project that we have emphasized already is simply the lack of time your BaU part-time staff have. One of the authors vividly remembers the first time he heard project work referred to as homework. He was working on a particularly contentious project in a large company, which required the consolidation and relocation of several contact centers. It was a stressful time for the experienced managers who ran these operations. In a meeting to discuss the approach, one of the senior managers complained that they were doing this project as homework, by which he meant he was having to do the work outside his normal workday, which was already fully scheduled. That phrase and its connotation has stayed with him ever since as he regularly works on projects where key people have a full-time day job too.

It is not just the time. People can hold only so much in their heads at a time. So many outstanding tasks, so many problems, too many worries. Switching between activities takes mental effort, especially if it is a different domain or different way of working. BaU part-time staff just might not have the time or mental capacity to devote to the project.

The People Project Triangle

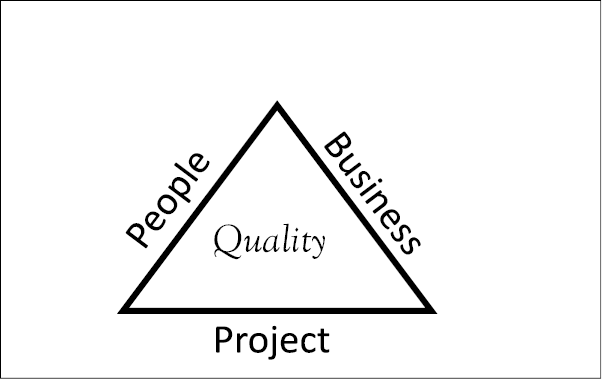

Earlier, we described the standard project management tool of the project triangle and its use to understand the constraints and trade-offs in projects between the variables of scope, cost, and money. We then described the composite project environment where staff with full-time day jobs must accommodate additional project work. This places pressure on the people, which impacts the progress of the project and the ongoing business-as-usual activities. There becomes a trade-off among these constraints, and so, another triangle suggests itself, the people project triangle.

The people project triangle is presented in Figure 5.2. It shows the relationship between people, the business, and the project. Again, the key concept is that you cannot improve all the variables at once. When the pressure is on, you must decide which variables take priority and which are sacrificed.

Figure 5.2 The people project triangle

As in the standard triangle, quality anchors the others together and sits in the middle. Quality here relates to business performance key performance indicators (KPIs); project delivery within budget, cost, and time; and people’s quality of life.

The business as usual of transforming resources into outputs that customers value and demand must continue. Schedules have to be operated, performance has to be maintained, and customer expectations have to be met. This is the lifeblood of the organization. If existing commitments are not met, then there are short-term financial consequences and long-term reputation consequences. If sales targets are missed, there are medium-term financial consequences, and if marketing campaigns are delayed, there are long-term financial consequences. These are unyielding pressures. The staff, even if on a project as well, have to do their day job. If they do not, there is visible pain.

Composite projects come in all sizes with all levels of urgency and importance. They are not the most mission-critical projects, but delay or failure is likely to have severe consequences, not least for the managers involved. The organization and the individuals may suffer reputation damage and visible pain.

We have left the people who work in the organization and are seconded to work part time on projects until last, because they are often the least considered on the trio of variables. As discussed in Part I, the lean organization has left its staff with little slack, and yet, they are expected to add project workload into their schedule. As a consequence, there may be impacts. Staff who find they are struggling to deliver fear for their reputation and may turn inward and experience stress and anxiety. They may turn outward to voice malcontent affecting morale and staff turnover. The impact of stress and staff turnover may not manifest immediately, but can rumble on for a long time.

We recommend introducing the people project triangle, to bring to the foreground and make explicit trade-offs that many organizations have been making unconsciously and implicitly rather than consciously and explicitly. We said earlier when the pressure is on, you must decide which variables take priority and which are sacrificed. In the case of composite projects, our experience is that management is not aware of this trade-off, and the consequence is that it is nearly always the people who take the strain and suffer the consequences.

In the rest of Part II, we will explore in detail the impact and risks associated in these three dimensions: the people who work in the organization, the business as usual, and the composite project.