Ensuring the project is set up well is important for all projects. It is particularly important for projects using team members who spend most of their lives in business as usual (BaU) and are doing the project as-homework.

Building a Team from the Project Members

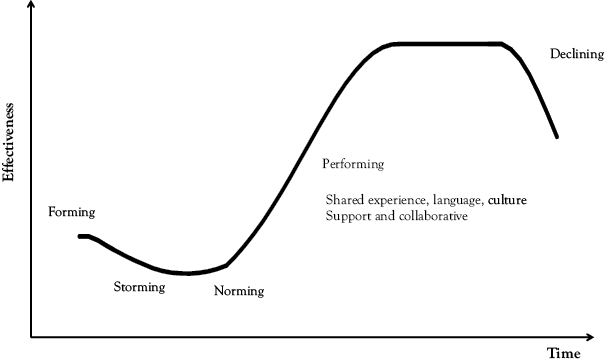

We covered team selection earlier, but once that is in place, the next step is to introduce the project manager, business lead, and project sponsor to the project members, and then meld those individuals into a team. With an all full-time dedicated group, this often happens naturally. Bruce Tuckman’s model1 for this is shown in Figure 15.1, as new people come together, there are personality conflicts, competition for influence, and communication difficulties due to different assumptions and outlooks. Through necessity, disagreements are resolved with accommodations and compromises, and misunderstandings are cleared up. This leads to increasing effectiveness as the group starts to function as a team. Effectiveness is accelerated as the team builds trust and increasingly works to each other’s strengths.

Figure 15.1 Tuckman’s stages of team development

However, this process may not happen naturally and particularly for part-time members who regularly go back to the comfort of their normal BaU team. You may have to coach transition through the stages.

A key tool is to build a shared understanding of the project’s vision, with the project team. This is achieved via the kick-off workshop, meetings with workstream leaders and members, and so on. This is useful to hold the team together and to drive the project forward. When difficulties arise and heads drop and shoulders droop, raise them by getting them to look up at the inspiring vision they emotionally committed to.

A buzz of being part of something important motivates. So, another useful tool to enhance morale is promotion of the project and the project team throughout the business. After the staff know about the project, the next interest is who is going to be doing it and so, the announcement of the team to the business can be used to promote the project and motivate the team members.

A complication for team dynamics is movement of people into and out of the team. This may be planned due to the changing project resource requirements or unplanned and forced by external events. Do not just assume a new team member will be easily assimilated. Plan for their arrival, induct them into the environment, and monitor they are positive and not disruptive to the smooth functioning of the team.

Understand Your Team

If you did not pick the team, spend time to understand the people and the way they work. They will be driven by attitude, aspirations, and fears, so you will not likely have total support and compliance. Has their past work and experience prepared them for any of the tasks on this project?

Consider having the team complete Myers–Briggs2 tests for them and you to learn how they may best perform as a team member.

This will help you build a sense of working as a team and not as individuals. If you make sure everyone understands how others depend on their output, you can instill a sense of not letting the team down.

Project Methodology

Do not overcomplicate things.

Project methodology, processes, and documents are there to help projects run smoothly and not act as a straitjacket. Formal structured methodologies and project management tools can be complex and frustrating for anyone not familiar with them. In some cases, there may even be a blend of techniques in play. For example, a workstream could be using agile principles to create software, while PRINCE2 is used in the construction workstream. The inexperienced or unsure project manager defaults to rigid adherence to the methodology. The PM who really understands the method and the purpose of each process and output can skillfully tailor the project documentation to the needs of the project, the business, and the people involved. Find a reasonable and workable compromise.

As-homework team members are unlikely to be intimately familiar with the documents and tools, so adapt and simplify as much as feasible. Aim for one-page documents such as plan on a page and status report on a page. Take the time to make documents clear and concise so that they can be reviewed by busy people in a few minutes. Even then, do not assume the message has been received and understood. If you need to communicate serious issues, then the best methods are a phone call or face-to-face.

Part of adapting the project environment is making it as familiar to the people as possible. Use terminology common to that business. Use existing forms of communication in expected formats such as visual boards and existing intranets. Tap into existing meeting structures such as weekly management meetings for quick updates. Use familiar surroundings such as nearby meeting rooms and war rooms.

Do not make the mistake of overestimating the project management knowledge of the as-homework staff. Team members may be reluctant to admit they do not understand the terminology or methodology, but equally, you do not want to patronize them. Make an informal assessment of their project knowledge during discussions and then, where necessary, educate the team. Your best opportunities for this are during early one-to-ones and during the kick-off and earlier-stage workshops.

If there is a project management office (PMO) function, then consult them, as they may require things to be done in a certain way and may be able to offer support in some areas. Do not be averse to challenging the PMO rules to avoid adding a level of difficulty with potentially little real project benefit.

Story: Rigorous Start up with

a Sound Business Case

This story illustrates the vital importance of ensuring the projects starts on a sound basis with a strong business case.

The business was involved in supplying outside broadcast services to TV companies.

Although predictable, the company had a highly variable demand for its services both across the week and across the year. Staff worked an annual hours contract, with hours being called off anytime across the year. They were also supplemented by a significant number of freelancers.

We undertook a review of its business processes and, in particular, its employment model in considering moving a large part of its staff to freelance status. Freelance rates were apparently favorable, and savings were to be had from avoiding the generous pension contribution, but there were redundancy costs (different for each person) to be considered.

With such complicated business and employment processes, they needed a sophisticated financial model to determine the value and impact of the proposed changes under varying demand growth assumptions.

To general surprise, the model revealed a long payback period and a poor return on investment for the switch. This meant that the management were able to avoid a costly and disruptive change to the business.

Initiation

In this section, we list out the steps we take so that a composite project is setup to succeed. It is intended to act as a checklist focused on the things specifically for composite projects:

- • Have a kick-off workshop event to set the stage. The goals are for everyone to get to know each other, create a collective vision for the project to focus minds and boost morale, brainstorm the deliverables, and explore the risks.

- • Project initiation document (PID). The PID may be a single document or more often collection of documents that defines the why, what, when, and who. Next, we focus on the aspects vital for a composite project:

- • The project manager creates the PID, but it should be issued by the project sponsor. As a person with hierarchal authority and reputation, this means it will register with people even if it is not read.

- • The document explains what the project is all about, but do not assume the message has been received. To confirm all the key stakeholders have understood and support the initiative, it is necessary to meet face-to-face one-to-one or with small groups. This ensures attention but, as importantly, allows you to gauge response, understanding, and commitment.

- • Sometimes, for a contentious project, it is worth having people physically sign the document. This can sometimes be brought out later in a formal way to reinstate commitments that have lapsed, but just the act of signing creates an internal strong commitment in people. The act of signing has strong cultural significance in our society that you can use.

- • Dwight D. Eisenhower said, “Plans are worthless, but planning is everything.” We certainly do not go that far, but we do endorse the sentiment that the benefit of the PID is not only the output document, but also the process of working together and the thinking that it forces on the team.

- • Scope. It is vital everyone knows what is going to be involved:

- ˏ Only then can as-homework members have any idea they have the capacity to deliver the project.

- ˏ It is also a vital tool in managing scope creep. It is inevitable that calls to add more better features will arise. A loose ambiguous scope definition leaves you exposed. By contrast, a tight explicit scope definition, along with the concepts of the project triangle and people project triangle, allows you to ensure the impacts are understood by the project board. In particular, the usual problem of the pressure on the as-homework staff is not overlooked. Your argument for properly resourcing any scope extension can be well evidenced.

- • Project team and responsibilities. Without this, it is impossible to commit to delivery or to determine how much time each person must devote to the project. Again, it is the as-homework staff that are most vulnerable and so most in need of clarity as to responsibilities.

- • Assumptions, constraints, and dependencies.

- ˏ A plan is about the future, and the future is uncertain. Rather than give up in the face of uncertainty, it is necessary to make educated estimates and forecasts and plan on that basis. However, ensure everyone agrees those assumptions are realistic.

- ˏ Publicizing how each person’s output affects others—

dependencies—especially on the critical path, is a great help to as-homework people who struggle to see far enough ahead to make those connections. A key role of the PM is to know which tasks to push and what can be allowed to slip and so sparing pressure on as-homework staff if possible. - • Communications plan. A plan of what information and what messages, to whom, by what media, and how often. The as-homework staff and their BaU managers need careful consideration, more on that later.

- • Detailed plan.

- ˏ Obviously, this is vital for the PM, but the process of creating this by workshopping it is of immense value in motivating and gaining commitment from as-homework staff who might be unfamiliar with the process. Start with the end in mind and focus on final and intermediate deliverables (product-based planning), as that is what people can envisage, and it is critical for people to see what the state will be at the end of each phase.

- ˏ Be realistic. The well-known expression “No plan survives contact with the enemy” is true for most projects and is one of the challenges that led to the development of agile principles. The fourth agile value is “Responding to Change over following a plan.”

- ˏ Help as-homework staff by making each deliverable small. A workstream responsible for a software output will be doing this if they are using agile principles. Large complex tasks are less likely to be done because they appear daunting and cannot be done without planning. So, do not expect the staff to sub-divide their own work, do it for them. Make deadlines more frequent and more achievable. It is good for their sense of accomplishment and morale and is good for the PM in identifying slippage early.

- • Initial risk assessment. Composite projects have risks unique to this kind of project, namely the interaction of the project workload with the demands of BaU. This depends on the nature of the BaU work and how predictable it is. Is the BaU customer demand and variety of the output unstable or unpredictable? If so, this will mean as-homework staff are uncertain what demands will be made on them by BaU at any time in the future.

- • Apply lessons learned from other projects.

- • Our experience with business projects is that this is the worst-documented aspect of a project. If the material exists, it is very valuable; if not, it is often worth investing some time to talk to participants on similar past projects.

- • The issues on past projects are frequently symptomatic of the way an organization works. It is then very helpful to run the team through lessons learned, or alternatively, learn some lessons from the problems experienced.

- • Mini PIDs.

- • The concept of a mini PID is to provide workstream PIDs. These documents are much shorter than the main PID, but require the PM and the workstream lead go through the same initiation thought process.

Story: Rigorous Initiation in Product Development

The following story illustrates how a sound initiation process can stop poorly thought through projects moving to implementation.

An organization was launching several products to increase sales in its customer service business. Given the scale of the activity, the organization required some experienced support to manage the process of selecting and implementing a suite of products.

One of the authors was engaged to support a team establishing a program of product developments. The team supported the franchise network and was charged with improving service revenues and customer satisfaction. There were several pilot products, so it was important that they were implemented properly to test the sales and service impact.

The key activity was a rigorous initiation process to ensure each implementation had been properly thought through and planned. We ran workshops for each product and, together, created mini business cases and short PIDs. This ensured we had a consistent method, and that we asked ourselves all the difficult but necessary questions. We were able to plug any gaps and identify risks before we started and before we committed effort and cost.

Several projects were unable to meet the criteria we agreed. This was a disappointment to the enthusiastic proposers, but the organization was better off not continuing projects with high risk of failure.

We created a simple review and reporting structure appropriate to the scale of the program to monitor the implementation stage.

The products that made it through this process were all implemented in full, or as pilots, during the year as planned. It re-emphasized the value of the project initiation process, even for small projects.

A rigorous initiation can sometimes be used after a project has been initiated, if that makes sense. In business, sometimes, moving quickly to grab an opportunity is a sound strategy when you know you can retrofit the project governance, provided that, too, is done very swiftly. We do not think it is something we would advocate as normal practice, but we have been engaged to do this from time to time, and it has been successful.

Story: Clarity of Objectives

The following story illustrates how clear, unambiguous objectives are vital to gain support of key business stakeholders, even if those objectives are uncomfortable.

An organization operating in the public sector embarked on a reorganization that included most departments. Their brief was fluid and affected by government policy, so their team was under constant review. They had to periodically bring in new skills, move staff into different roles, and in some cases, let them go.

One of the authors supported the organization over a 10-year period and four of the reorganizations. Each time, we spent the correct amount of time to prepare the project, the organizational proposals, consultations, and so on. However, the most valuable part of the preparation was the frank conversation to agree on the objectives.

There were always very difficult decisions to make. The impact of these decisions would have a serious and unexpected impact on staff members. We found that it was vital, within the project team, to fully understand what we were trying to achieve, even if some of the objectives were very uncomfortable.

Communicating to the staff during a reorganization is tough anyway, but clarity of purpose reduces the risk of messages being misconstrued.

1 Bonebright, D.A. 2010. “40 years of Storming: A Historical Review of Tuckman’s Model of Small Group Development.” Human Resource Development International 13, no. 1.

2 See Myers-Briggs Foundation, https://myersbriggs.org