11From Canada: Applying POLCA in a Pharmaceutical Environment

Guest authors: Justin Bos and Susan Ferris

Patheon is a global pharmaceuticals contract development and manufacturing organization (CDMO). Patheon offers a simplified, end-to-end supply chain solution for pharmaceutical and biopharmaceutical companies of all sizes. The Toronto Regional Operations site specializes in high-potency oral solid dose development and commercial manufacturing.

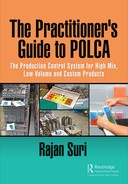

A typical process flow in an oral solid dose plant has five stages: Dispensing (where the materials are measured to the exact amounts required); Granulation (where the materials are combined to create a uniform blend); Compression (where the blend is formed into tablets); Coating (where the tablet is coated with a liquid solution); and Packaging (where tablets are packed in bottles or blisters). Each of these manufacturing stages is completed on a different workcenter, so each order will run on several pieces of equipment before it is ready for shipment. We have eight granulators, eight compression machines, five coaters, and seven packaging lines, and in principle, an order can be routed from a workcenter to any of the workcenters in the next stage, resulting in a complex collection of possible routings, as shown in Figure 11.1.

Figure 11.1Schematic of all the workcenters and possible routings.

Since Patheon does not manufacture its own products, it operates make-to-order plants, managing orders from multiple clients that share Patheon’s equipment capacity. To further complicate matters, each product must be validated on specific equipment to ensure repeatability. This creates rigid manufacturing paths that cannot be easily changed, and, when combined with the large number of routings along with volatile forecasts, makes for a challenging planning environment.

Why Did We Pursue POLCA?

In 2011, prior to POLCA, the plant was finitely scheduled using the MRP portion of our ERP system. This schedule required almost constant revision to keep accurate when there was any deviation from it. In addition, gaps in the schedule were filled to keep machines utilized and it wasn’t long before work-in-process (WIP) started to pile up in front of bottlenecks. In our plants, WIP poses an extra threat: it must be consumed quickly or else it requires testing to confirm that it is still safe to use.

More WIP in the system also meant that our production lead time—as measured from the start of the first stage (Dispensing) to the end of the final stage (Packaging)—was starting to creep up to over 20 days. This resulted in more schedule changes in an effort to avoid stocking out the market of our clients’ life-saving drugs. Those schedule changes often forced us to run in less optimal sequences, further compounding the problem.

We had been focusing our Operational Excellence efforts on constrained resources, trying to maximize Overall Equipment Effectiveness (OEE). We use the traditional definition of OEE, which takes the total of the standard run-time hours for products made on a given workcenter, divided by the total available hours on that workcenter, both for a given period. We noticed that from our focus on OEE, the individual workcenter results were promising, but we weren’t seeing systematic success. Bottlenecks would shift depending on client order patterns and our throughput had flatlined, despite our hard work. We understood that we had to change the way our plant was planned. We needed to stop trying to push product through and instead begin to pull it.

A traditional Pull system, such as Kanban, was not suitable in our high-mix, low-volume operations (see Appendix C for more on this point). We started researching more recently introduced systems, including CONWIP (see Appendix C) and POLCA. After a preliminary analysis of both these systems, we concluded that for our environment POLCA was the best option for two main reasons. To understand these reasons, note that CONWIP assigns a loop to each particular routing from the start of the first operation all the way through the last operation for that routing. So, the first reason for our choice was that, as mentioned, our routings can go from any workcenter at one stage to any of the workcenters at the next stage. Referring to Figure 11.1, this means that there are 8 × 8 × 5 × 7 = 2,240 possible routings in our factory, requiring 2,240 different CONWIP loops to be managed with cards. In contrast, POLCA would require at most 147 loops—or more than an order of magnitude fewer loops. (Each workcenter needs a loop to all its downstream workcenters. From Figure 11.1 this results in 8 + 64 + 40 + 35 = 147 loops.) Second, the CONWIP loop signal comes only from the end of the last step back to the start of the first step. With our lead times of around 20 days, we felt that this would be a highly delayed signal, and we wanted more frequent signals plus tighter coupling between each stage, and POLCA offered both of these capabilities.

The POLCA Kaizen Workshop

POLCA began the same way many of our Operational Excellence projects do—with a five-day kaizen workshop. A small team was assembled with representation from Production, Planning and the Operational Excellence department. The first day was spent getting the entire team up to speed with the principles of POLCA and working through a white paper, “How to Plan and Implement POLCA” by R. Suri and A. Krishnamurthy, available from the website of the Center for Quick Response Manufacturing. Our team felt that POLCA would be able to address the scheduling and WIP issues we had been experiencing, but the team still had one reservation. A change of this magnitude would pose a substantial behavioral challenge for both our management and our front-line employees at the site. We had to come out of the workshop with a robust change management plan.

Deciding on All the Fundamentals of the POLCA System

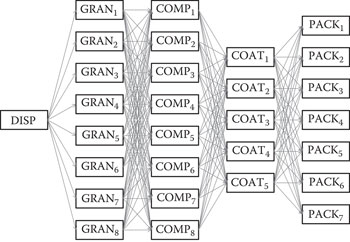

We started by designing a spreadsheet that would become a working document for all our developments throughout the week. Product forecast and routing information were loaded into the spreadsheet and we began to identify the POLCA loops. As already mentioned, our plant was so complex that by the end of the exercise most workcenters were connected to all workcenters in the following stage. We went with the recommended standard design for the POLCA cards. Specifically, each resource was given a unique color that is used on the cards and on the POLCA Board. Figure 11.2 shows the generic layout of our cards. As shown in the figure, we followed the advice to assign a unique serial number to each card, to enable auditing of the cards. We also laminated the cards to help them survive a factory floor environment!

Figure 11.2Design of the POLCA card.

To calculate the number of cards, we chose a three-month planning period because we have a 90-day firm order window. We used the standard formula (see Chapter 5), but then minor adjustments were made to the number of cards. For example, more WIP (i.e., POLCA cards) was permitted before the final manufacturing stages because we wanted a larger buffer in the event of an upstream manufacturing disruption. Since our product mix is constantly changing, we also decided that we would we recalculate the POLCA card requirements every three months based on our clients’ upcoming forecasts, and that minor adjustments would be made on the floor to add/remove cards as required based on observing the system operation for that quarter.

The team created a tabletop game to simulate the manufacturing steps and the operation of POLCA in our factory. We tested different card levels to understand how it would change the flow of the batches. There was a lot of discussion around the quantum, i.e., what amount of work a POLCA card should represent (see Chapter 5). Our products have significant variation in operation times at the machines, so initially we were inclined to make a POLCA card represent a unit of time (e.g., four hours). However, this would require our front-line employees to collect multiple POLCA cards based on routing times before having the green light to start a particular batch. After running simulations, and ultimately prioritizing simplicity over accuracy, we decided to have a POLCA card represent a single batch. This also made sense in terms of quality and integrity of product, as each batch is earmarked for one (single) customer.

Finally, we decided that the Release-and-Flow version (RF-POLCA) would work fine for us. While individual routings may differ, all batches have the same number of routing steps, and as already mentioned, once a batch is started it is important to keep it moving for quality reasons. So, we felt we didn’t need to re-sequence jobs downstream, but simply to control for capacity constraints and WIP buildup in those downstream areas. Therefore, the Authorization Date for each batch is assigned only for the first stage. This date is calculated by our ERP system via standard MRP logic that uses the planned lead time for our start-to-finish production operation.

Rules to Break Rules

POLCA was not necessarily designed with the pharmaceutical industry in mind. There are specific challenges that we face in our manufacturing operations, and we needed to come up with creative ways to overcome them while still working within the general rules of POLCA. The POLCA system design rules do recognize that you need a way to handle real-world exceptions, and there are techniques such as Safety Cards explained in the design rules (see Chapter 6). Using these ideas and after some additional brainstorming, our team came up with the idea of three special types of cards: Campaign Cards, Quality Deviation Cards, and Bullet Batch Cards. Each is a temporary card that is requested by Production and destroyed after a single use.

Campaign Cards are issued when Production wants to execute an extra batch of the same product without waiting for a capacity signal (POLCA card) from the relevant downstream resource. Since we use the same equipment to manufacture multiple products, changeovers from one product to another can be time-consuming. The Campaign Card authorizes controlled overproduction of a product where normally we would pause and wait for a card to return. During this pause we would need to change over and begin making another product based on a different POLCA card, and this would cause some loss of capacity due to the changeover time.

Quality Deviation Cards are issued when a batch has a quality hold since it can sometimes take days to disposition it as accepted or rejected. During that time, we want to authorize upstream resources to continue making product. So, this temporary card is issued and kept with the batch on hold, while the original POLCA card is sent back to the previous process to signal capacity. (Chapter 6 further explains the need for such a process.) If the batch is ultimately accepted, there is one additional batch ahead of the downstream resource, but the WIP level will return to normal once the card is destroyed after use.

Both the Campaign Card and the Quality Deviation Card are identical to the normal POLCA card, but we put a yellow border around the outside with large words such as “CAMPAIGN CARD” on the top to highlight that it is a different card. These cards are not created beforehand, but they are printed and issued when required (and not laminated like the other cards). Both these types of cards can be issued by Production Management.

The final custom card, the Bullet Batch Card, is used for extreme situations when the execution of a batch must be expedited (e.g., there are clients on-site observing a batch from start to finish, or there is a market stock-out). A Bullet Batch Card enables that batch to move as quickly as possible through the system, jumping any queued batches in WIP. This is extremely disruptive to the batches already in the system and their lead time will increase, which is why it reserved for the most critical of circumstances. A Bullet Batch Card can only be issued by senior leadership: it requires both the Production Director and the Supply Chain Director to sign off on its use. This card does allow us to be flexible and respond to our clients’ needs when absolutely necessary. However, because it is also disruptive to the overall operation and to other batches, funneling the decision through two senior people ensures sufficient scrutiny that it is in the best overall interest of our factory. Bullet Batch Cards are pre-made and laminated, and, in fact, we have only two of these cards! Interestingly, this has not been a problem. As described later in this chapter, with the POLCA system in place, better overall control, and much shorter lead times, we have found that the Bullet Batch Cards are rarely used—they have been issued only two or three times per quarter.

Senior Leadership Plays the POLCA Game

As mentioned above, coming from an ERP/MRP environment, implementing a system like POLCA involved considerable mindset challenges. It was a foreign concept for most of us, even for those who had Lean training. While the whitepaper was read by the whole team, some members of the team struggled to understand the mechanics of POLCA until they were involved with running scenarios through the game we had developed. So we knew that in order to get other people on board, we needed to have them experience the game as well. Thus, once we were confident that we wanted to pursue POLCA, the team concentrated its efforts on honing the game.

The five-day kaizen ended with a report-out to senior leadership at the site. As has been stressed in other sections of this book, implementing POLCA requires top management buy-in and commitment, so readers may find it useful to see the level and breadth of management that attended our report-out. Attendance included our site General Manager and direct reports from several business units. These people included the Senior Director of Pharmaceutical Development Services, Director of Supply Chain, Director of Production, Director of Operational Excellence, and Director of Business Management. Also in attendance were all five people who were directly involved in the kaizen activity.

Our findings and recommendations were summarized in a slide presentation, but we also had them play the game to demonstrate how POLCA would work for our factory. The first round was played with our existing ERP/MRP conditions (i.e., a finite schedule, maximizing the OEE of individual machines). During the round, we simulated machine breakdowns and client escalations to underscore how disruptive those things could be to the system. The second round was played using POLCA. With the POLCA cards and rules in place, managers could see that the WIP was more balanced, so that even when there was a breakdown or client escalation, the system experienced little disruption. At the end of each round three metrics were measured: the amount of idle time at each machine, the amount of WIP in the system and the total batches produced (throughput). Comparing those numbers made it clear that not only did POLCA work in theory, but it would work for us. After playing the game, senior leadership was convinced and they sponsored an implementation of POLCA for the whole factory.

Training, Training, Training

It took 12 weeks to completely implement POLCA. Most of the design was done during the workshop, but the majority of those 12 weeks were spent training nearly every business unit at the site. To truly appreciate the magnitude of this training effort, you should know that we held more than 20 training sessions that were attended by over 250 people in production and another 80 in support roles! This may sound like a lot of organizational time spent on training, but we knew we could not overdo the communication for this magnitude of change. In each session, overview slides were presented and then the participants played the POLCA game. There were a lot of questions and concerns, and each was addressed before moving forward. For example, people from Planning were reluctant to let go of their traditional tasks of scheduling workcenters, and to focus on more high-level capacity planning. Yet, on the other hand, staff from Production were excited because they were constantly dealing with changing plans and welcomed the ability to have more clear visibility into their destiny. Such discussions helped to bring the teams to a mutual understanding. We needed to have complete buy-in from all these people to not only understand but support the initiative.

Training the front-line Production staff was more tactical and got into the finer details. Where would the cards be stored? What would the cards look like? What would you do if you found a card on the floor? How could we audit the quantity of cards? What would happen if we didn’t use cards to authorize production? Every single Production employee attended one of these training sessions, sometimes more than once. These were the people who would make POLCA a great success or a great failure. It was absolutely critical that they understood not only what to do but why it was so important to follow its rules.

The POLCA Boards and POLCA Dashboard

With the training complete and the POLCA cards laminated, we had to figure out how to store and manage all the cards. In our highly regulated environment, every executed batch has controlled documents called a “batch record” that travels in a transparent plastic briefcase. This offered the perfect vehicle to transport cards when they were in use. We labeled and hung steel seven-pocket wall racks to be our POLCA Boards, and this is where batch records waiting to be executed on a specific workcenter queue up (Figure 11.3). Unused cards for downstream resources are stored in the bottom pocket, so before starting a batch, Production staff can confirm that the correct downstream card is available.

Figure 11.3POLCA Board showing the pockets for the batch records, unused POLCA cards (in the bottom pockets), and POLCA cards that need to be returned (top right holder).

After producing the batch, the card from the previous stage is returned to its home POLCA Board. Again, readers may find our decision on this process helpful. We first thought about having designated “runners” for returning cards. But then we realized there was enough traffic throughout the day that we could just set up a mailbox system and make returning POLCA cards everybody’s job. (This is one of the options recommended in Chapter 5.) So, if someone was walking past a POLCA Board and noticed cards in the mailbox (the box labeled “POLCA CARD HOLDER” on the top right of Figure 11.3), they would pick them up and take them to the other POLCA Board if they were going that way. At a minimum, this would happen every two hours anyway with our scheduled breaks. This procedure has worked well for us, and it has also helped to drive ownership of the system to everyone in the factory.

Instead of having a POLCA Board at each workcenter, we have four locations throughout the plant where these POLCA Boards are placed for nearby equipment. This is because we have a lot of workcenters, which are divided into zones with leadership oversight for each area, and we aligned the POLCA Boards with those zones to enable decision-making for a zone to be done in one place. In addition, our WIP is too large to be stored directly in front of resources where it would be visible, so having these POLCA Boards clearly displays how much WIP is actually waiting for each resource. This also allows front-line employees to easily identify bottlenecks and understand priorities.

Taking that idea one step further, we developed a large plant-wide “POLCA Dashboard” where batches are represented by 2" × 3.5" magnets (Figure 11.4). Prior to implementing this board, managers and support departments would refer to a printed Master Production Schedule to determine what to do next and when things were expected to happen. This printout was harder to absorb as it was not really visual, but the real downside was that our schedule was very volatile so the printout was obsolete almost as soon as it was printed! The POLCA Dashboard offers a live picture of where all the batches are, and can be continuously updated. It has become a central location where all departments come to discuss strategy and execution sequence based on current events. If a machine breaks down, we discuss it at this board and look for batches that can be started or expedited to avoid the resource with the breakdown. The POLCA cards and decision rules would naturally create the same response, but this large visual board offers a macro view of what the cards are doing and supports buy-in from employees and supervisors about why changes are occurring.

Figure 11.4Plant-wide POLCA Dashboard.

Not everyone embraced the POLCA Dashboard at the beginning. Some considered it cumbersome to manually move magnets from resource to resource. However, it wasn’t long before the benefits began to outweigh the effort. A proud moment for the project team was when employees started improving the Dashboard and using it to track additional information to make their work easier; like proud parents, that’s when we knew the Dashboard had been accepted. A few months after the POLCA launch we wanted to permanently capture some of the improvements, so we redesigned the Dashboard. As we were taking down the old Dashboard, there were concerned looks from people coming to the Dashboard for information. We had to assure them that we weren’t taking it away, but trying to make it better.

Life with POLCA

Within weeks of our launching POLCA the product flow through the plant had already improved. Within three months our metrics were showing sustained improvements:

Production lead time was reduced from over 20 days to around 10 days (a 50% reduction).

On average, we find we are using only about 80% of the total calculated number of POLCA cards in the system. When combined with the 50% lead time reduction, there is a substantial reduction in WIP; a stark contrast from having difficulty moving through the plant because WIP rooms were crammed full and hallways were storing the overflow.

Maybe most impressively, and most impactful to our business, the throughput increased 20%, as measured by the number of batches produced. (Although individual batches vary significantly in their demands for equipment, over a longer period this aggregate number shows a clear trend.) Finally, we saw a systematic improvement throughout the entire plant (rather than individual resources), as measured by another aggregate metric, kg produced/FTE (FTE stands for Full Time Equivalent, a common metric for headcount in organizations).

Escalations still happened but they became less disruptive to the shop floor. In the past, shop floor staff would be pestered to expedite certain batches, but at the same time they would get conflicting direction causing frustration as well as more changeovers. With POLCA in place, most of the time the shop floor people are unaware that a batch has even been escalated, because a 10-day shop floor lead time offers the flexibility for sales and planning to respond to clients’ needs without changing priorities of batches already in production.

Production staff, who often knew best, were empowered to make real-time scheduling decisions rather than blindly following a schedule that had been created days ago by someone in an office.

Pursuing a project like POLCA was a risk at the time. It truly changed core business practices all the way back from how we procured materials (to ensure flexibility), how we scheduled batches, and how we executed them. Yet we were able to successfully apply the concepts and adjust them to our unique situation.

A change of this magnitude would not have been adopted without the constant training and communication. Anyone looking to implement POLCA should not underestimate those aspects of the project. Our plant was such that we could not pilot the concepts of POLCA in a small area. We do, however, recommend that others start this way if possible. It would have been much easier to launch and control if the scope were smaller.

POLCA has changed the way Patheon runs its business. The improvement in production lead time has made us much more flexible and agile (words not typically associated with our highly regulated industry), allowing us to respond quickly to our clients’ ever-changing needs. POLCA has enabled continued growth at our site and now that it is so embedded in our culture, it’s hard to imagine ever going back to finite schedules and WIP in our corridors!

About the Author

Susan Ferris joined Patheon in 2002. Having worked in various positions, she currently holds the position of production director. After completing a Black Belt program within Patheon, she was assigned a project to improve the overall lead time and throughput in Production, which led her and the rest of the team to POLCA. Susan holds a Bachelor of Science degree with Honors in Neuroscience from Brock University in St. Catharines, Ontario.

Justin Bos joined Patheon in 2010 and currently holds the position of Manager, Operations Strategy. He was the Operational Excellence Black Belt that supported the POLCA implementation at the Toronto site. Justin studied Mechanical Engineering Design at Conestoga College in Kitchener, Ontario.