CHAPTER 7

Does Descriptive Representation Facilitate Women’s Distinctive Voice?

Who is she, what does she want, and what sort of action shall she undertake? Is she a human being who can give a spoken account of herself? If so, what language does she speak?

—JEAN BETHKE ELSHTAIN1

IN A STRIKING ILLUSTRATION OF COOPERATION, psychologists studying one of our cousin species have found that lab rats engage in a persistent effort to liberate their caged fellow rats. They do so even when they gain no reward, are denied the company of the liberated compatriot, and despite giving up a portion of a favorite treat. The rats had to overcome their fear of the situation and to learn to open a door to a cage, a highly challenging task. The lesson for humans—that we too may be hardwired to help each other—might end there, but for one more wrinkle. Among rats equally adept at opening the door, the females freed the trapped compatriot much more speedily and consistently than the males (Bartal, Decetey, and Mason 2011). This gender gap in compassion is no surprise to students of the human species. Back in the human world, women, too, tend to be more other-regarding and prosocial than men, whether by nature, nurture, or both.2

But humans, unlike rats, have developed organizations and institutions. In these complex forms of social organization women are not always able to act on their prosocial inclinations. Some institutions facilitate the impulse to help those in need, while others stand in the way. What are these institutions, and how do they inhibit or empower women’s voice of care and compassion? In particular, we ask: does increasing the descriptive representation of women increase their substantive representation—specifically, their chances of voicing women’s distinctive concerns? Put differently, does increasing the proportion of women in a deliberating body also affect the content of the discussion, and how do institutions moderate the effect of numbers on the words uttered in the conversation?

One of the virtues of our experiment is that it allows us to examine what people say in their own words, and to connect those words with their attitudes and actions. A known virtue of the controlled experiment is “internal validity”—in this case, confidence that the decision rule and gender composition are the only possible causes of the effects we observe. But a controlled study provides an additional opportunity—careful measurement. It allows us to carefully track individuals’ speech and link it with pre- and postdeliberation preferences, attitudes, and behavior. That way we can systematically analyze who says what under what conditions. This tells us if women mention more issues of distinctive concern to women when they occupy a more equal position with men in the group, holding constant the attitudes they carry with them when they arrive to deliberate. It can also tell us how their speech affects the decisions they reach after they speak.

There are important consequences to women’s representation. As we will detail, women far more than men prioritize the protection of vulnerable and poor populations and support government intervention on “compassion” issues (Hutchings et al. 2004). Were women to gain more equal standing and authority, deliberations in public settings may well come to reflect a different set of priorities.

IS THERE A DIFFERENT VOICE?

Our question is whether conditions that promote equal participation in deliberation also produce more speech about women’s distinctive priorities. But before we can address that question, we first explore whether women have distinctive concerns and what those might be.3 In earlier chapters, we have already hinted at some fairly robust though small- to moderately sized general differences between the views of American men and women. Women tend to be more empathetic and prosocial than men. Now, what does this mean for women’s and men’s distinctive political priorities?

Women currently hold a number of political perspectives and priorities that differ from men’s. In advanced industrialized countries, women now tend to vote more left wing than men by about ten points, and their ideological position lies to the left of men’s (Inglehart and Norris 2010, 130). In the most recent review of the US gender gap in public opinion, conducted on two large national samples with extensive political assessments (American National Election Study and National Annenberg Election Study), political scientist Melody Crowder-Meyer (2007) finds that even after controlling on variables such as party identification, women are more likely than men to believe that “it is problematic that not everyone in the U.S. has an equal chance in life,” are considerably more supportive of government’s role in addressing economic distress and social needs such as health care, prefer less room for the free market, and are more concerned about economic inequality. Women are more eager for government spending on the poor, elderly, and children. Women are also more racially egalitarian (Hutchings et al. 2004).4

Even more relevant to what people will say in a deliberation than their stands on issues are their issue priorities—the issues they believe are most important for the country and those on which they rely the most in choosing among parties or candidates. Especially pertinent are responses to open-ended formats, where people speak in their own words about the nation’s pressing needs. The largest gender gaps are in these priorities, with women much more likely than men to view poverty and economic inequality as an important problem. As Crowder-Meyer summarizes, women are “eighty percent more likely than men to mention poverty or homelessness” (2007, 13).

Women’s priorities differ most from men’s on the topic of children. Women are “two and a half times more likely than men to mention children’s issues as a most important problem” (Crowder-Meyer 2007, 14). Perhaps most strikingly, “the least commonly mentioned most important problem for men is children’s issues, while women are more likely to mention these as a problem than illegal immigration, taxes, outsourcing, and energy and gas prices” (Crowder-Meyer 2007, 14).

Additional evidence about women’s distinctive priorities comes from their contemporary behavior. College majors that serve populations in need are overwhelmingly female—health (85%), education (77%), and psychology and social work (74%) (Carnevale, Strohl, and Melton 2011). Women are more likely than men to spend on children in the household (Lundberg et al. 1997). When women’s income increases, measures of their daughters’ well-being rise (Duflo 2003; Thomas 1990). The same holds for political behavior. Female activists and officials tend to prioritize issues of children and family and are more likely to work to pass measures that benefit them (Burns, Schlozman, and Verba 2001; Carroll 2001). Among people driven to action on a specific issue, by far the biggest chunk of women is active on the issue of education—no matter if they are advantaged, disadvantaged, married, single, or whatever. The biggest chunk of men is active on the issue of taxes—no matter if they are advantaged, disadvantaged, and so on; in fact, even fathers are more likely to participate on taxes than on education (Burns, Schlozman, and Verba 2001, 128–29). The biggest difference in the type of organization that women and men join is in educational associations (Burns, Schlozman, and Verba 2001, 78). This priority has a long history. For many decades before the law guaranteed woman’s suffrage, women were active in education (Burns, Schlozman, and Verba 2001).5 The needs of children thus take a position front and center for women, far less so for men.

Further evidence about priorities, and people’s willingness to act on them, comes from a very different setting, and one that generalizes well to the discussions we studied. When men and women are asked to render a verdict in a simulated trial of first-degree sexual assault on a six-year-old child, women tend to convict and men to exonerate (Golding et al. 2007). So in small group deliberations, as in survey and real world settings, women tend to place a high priority on the needs of vulnerable people, and significantly more than men.

Some issues emerge as distinctive priorities for men. Men are more concerned than women about financial issues—outsourced jobs, energy and gas prices, and taxes (Crowder-Meyer 2007). We will make use of these issues as a basis for contrast with the issues that women tend to emphasize.

In all, women are more concerned with children and the needy than they are with taxes or prices. Men’s priorities are the reverse.

HOW GENDER COMPOSITION MAY MATTER

As we said in chapter 1, meetings mean discussion in a small group setting, and discussions in small groups in turn typically mean that women interact with men. Gender role theory provides a good starting point for thinking about what happens in the course of this interaction. To recap our earlier discussion: this theory posits that the greater the number of women in the group, the more that women will be inclined to express their views. Women are probably reluctant to speak to their distinctive concerns when surrounded by many men and when the task is a collective decision on a matter that is not defined as a domain of competence for women. Women continue to be less likely than men to view themselves as qualified to deal with politics, to talk about it, to tell others what to think or do about it, and to decide it. That is, women view themselves in a way that gives them lower status as members of a group discussing politics. And men may view women accordingly and act to reinforce and further depress women’s low status in their group. The more men in the group, the stronger these effects are likely to grow.

In addition, women are socialized to engage in cooperative discussion, while men tend to engage in more competitive and assertive forms of exchange. The more men in the group, the more the discussion is likely to reflect a norm of assertion. A balance of members tilted toward men may create stereotypically masculine characteristics for the exchange. The discussion dynamic may take on the characteristics of individual agency rather than mutual assistance.

For these reasons, gender role theory predicts that when women are the gender minority in discussions of politics, they not only speak less, feel less confident, and exercise less influence than men, they will also be less likely to bring up views that society deems women’s concern, and that men may not share. The fewer women in the group, the less we will hear women’s distinctive concerns.

We also revisit the enclave hypothesis from gender role theory. We ask whether all-female groups act as a protected space that fosters women’s full participation. Here we investigate specifically whether gender homogeneity produces a stronger voice for women’s distinctive issues.

However, as we have emphasized, all this is subject to a big fat “it depends.” And what it depends on is the decision rule. Scholars have long known that unanimous rule creates norms of consensus and inclusion. If you want people to cooperate, yoke them to each other, up the stakes, and don’t give them a way out. That is, in a nutshell, what unanimous rule can do. What it can do for women specifically is to bring their distinctive concerns into the discussion. Unanimous rule can compensate for the disadvantages of status in the group. But as we noted in earlier chapters, unanimous rule is a double-edged sword; it can help women in the minority but hurt women in the majority. It may prevent women from leveraging the power of numbers when they are the majority. For the same reason that minority women do better under unanimous than majority rule, majority women may do better with majority rule than with unanimous rule.

We expect that the frequency of women’s references to issues of distinctive concern to women will shift with the circumstances of women’s representation in deliberation. When women are a numerical minority under majority rule, they speak up less often and carry less influence in the group, as we detailed in chapter 5. But our argument is that the loss of authority and standing also affects what women say when they do contribute to the group discussion. Lacking empowerment, they may feel not only less qualified to speak but also specifically more reluctant to speak about their distinctive priorities as women, unless protected by unanimous rule. These settings may make salient women’s tendency to view themselves as less expert and competent in politics. The norms created by unanimous rule may help women by signaling to them that their distinctive concerns are a legitimate topic of conversation. This effect can be seen in contrast to circumstances where women participate less than men.

Specifically, our interaction hypothesis predicts the following: (1) Women will mention care issues the least, and succeed the least in aligning the group’s decision with those issues, as minorities under majority rule, because their low numbers disadvantage them. (2) Women will mention care issues most, shifting the outcome accordingly, as majorities under majority rule, where they benefit from high numbers without the encumbrance of a consensus norm empowering minority men. (3) Minority women will mention care issues, with corresponding outcomes, more under unanimous than majority rule, while (4) majority women will do the reverse.

Thus our interaction hypothesis is a departure from the hypothesis of gender role theory. Our hypothesis makes the same prediction that gender role theory does about the benefits of increasing numbers of women, but only under majority rule. It contradicts gender role theory by arguing that minority women are not inevitably quiescent about women’s distinctive issues when they are a minority, because unanimous rule protects them. Finally, it adds predictions about the disadvantages majority women under unanimous rule experience.6

A final caveat is in order: as in our earlier analysis, we need to address the possibility that differences apparently due to gender are spuriously caused by preferences or attitudes correlated with individual gender. We examine deliberation about redistribution, so political attitudes, especially regarding egalitarianism, are a possible confounding factor (Crowder-Meyer 2007; Shapiro and Mahajan 1986). We control for the individual’s egalitarianism and for the number of egalitarians in the group. We also replicate the results with controls on the person’s predeliberation redistribution preferences and their membership in the predeliberation preference majority.

DATA AND METHODS

As we noted in chapter 4, participants in our experiment were told that they would be performing tasks to earn money and that the money they actually received would be based on a group decision about how much, if any, income redistribution to undertake, using unanimous or majority rule. We provided an explanation of several principles of redistribution and instructed participants to reach a group decision that would not only apply concretely and immediately to themselves but also could apply hypothetically to society, in order to generalize beyond the lab to the decisions people make about redistribution in politics. And as we explained in chapter 4, groups followed these instructions by exploring together how the principles would work outside the experimental setting.

Here we focus on the issue content of the group discussions by examining the specific words participants used. Our word categories correspond to the issue priorities we identified above as of distinctive concern to women: (1) children, (2) family (as a related concept to care for children), (3) poor, and (4) needy. For contrast, we chose three other categories for the purpose of discriminant validity: (1) rich, (2) salary, and (3) taxes. “Rich” resembles children, families, and the poor in referencing a social group, but it is not a social group that women prioritize. It serves as a placebo for references to social groups. The remaining two categories (“salary” and “taxes”) reflect the distinctive priorities we identified above for men. We expect that references to issues of distinctive concern to women will rise in the conditions that give rise to gender equality, while references to the remaining categories will not.

We chose not to define women’s distinctive priorities based on the most frequently used words uttered by women and those uttered by men in our discussions, because that would be tautological. That is, we want to see how the conditions alter the frequencies of topics that women care more about, and thus we cannot use that same frequency to define the topics that women care more about. Instead, we rely on the variety of settings listed above to reveal women’s, and men’s distinctive priorities, including their choice of occupations, their budget priorities, their responses to questions about the nation’s most important problems in one-on-one survey interviews, and so on. That way we are not contaminating our measure of women’s distinctive priorities with the effects of women’s status in the measurement situation. We can get a clean measure of the concept of issue priorities by defining it a priori and see if it moves up or down with the conditions in our study.

We defined the categories using standard dictionaries for words associated with the topics of children, family, needy, and poor, and for rich, taxes, and salary, following the synonyms of each word in turn to their synonyms, and ruling out false positives by human checking. We also checked this list against related category lists in the Linguistic Inquiry and Word Count software (LIWC), a widely used program for linguistic analysis in the behavioral sciences, to ensure that we did not miss any relevant words (Newman et al. 2008). We use the LIWC software to conduct the word counts and calculate the percentage of the person’s total words for each category, though we do not use LIWC’s predefined categories since they are neither as comprehensive nor as relevant for our needs as our custom-constructed and human-verified categories.7 See chapter appendix B for the list of words.

We replicated our results with another method, using the TM module in the R statistical package. This method differs from the other in using only the most-frequent words the speakers in our sample uttered. This method first identifies the words most frequently used by our sample as a whole, regardless of their relevance to any topic. It then produces for each word its proportion of each person’s total words. We classified these most-frequent words based on their relevance to the topics we identified a priori above. Thus this method guards against the possibility that we are missing some frequently used, relevant words.8

We compute two versions of the dependent variable: (1) a dummy variable indicating whether or not the person mentioned any words in that category at least once (Mention), and (2) the number of the person’s words falling into the category (Frequency) per one thousand words spoken.9 When multiplied by the total number of women in the group, even small individual increases in Frequency can mean dramatic changes in the number of times the concept is raised overall during the group’s deliberation. In a twenty- to thirty-minute conversation, for example, raising a topic an additional nine to ten times represents a significant shift in the focus of the discussion.

WHEN DO WOMEN TALK ABOUT ISSUES OF DISTINCTIVE CONCERN TO WOMEN?

As we saw in chapter 5, descriptive representation elevates women’s participation and perceived influence, but the decision rule fundamentally alters this effect. When women are assigned to be the numerical minority in groups instructed to decide by majority rule, they are significantly less likely to speak than anyone else. In other words, minority women under majority rule speak less than men in their groups, men in the same minority status, and women in other groups. Unanimous rule seems to protect minority women’s deliberative participation from the inequalities that arise when women are a minority, though unanimous rule also empowers men when they are the numerical minority, leading them to participate at disproportionately high rates. Increasing the descriptive representation—that is, women’s proportions—under majority rule increases not only speech participation but other forms of substantive representation as well. The less any person spoke (woman or man), the less influential they were rated by other members of their group, so that low descriptive representation depresses perceptions of influence in the discussion in part by affecting quiescence.

With those findings in mind, we now turn to the effects of experimentally induced descriptive representation and decision rule on the issue content of deliberation. Our main interest is how often women discuss the topics we identified as distinctive to women—namely, children, family, the poor, and the needy. We will refer to these issues as “Care” issues, and the issues of salary and taxes as “Financial” issues.

Such references can be found throughout the transcripts. For example, in the midst of a discussion about how much is needed to survive in today’s society, a woman asks, “Let’s say there’s one person who’s bringing the income and then a spouse and a child or something like that, or you could even spend it as a single, like, mother who’s working with two kids. How much do they need to get by or something like that?” To this question, another female participant replies, “Oh, goodness, I’d say a single person raising two children? At least 50 [$50,000], I mean because if you figure you’re keeping a roof over their head, food on the table, clothes, electricity, plumbing, I mean just paying the minimum bills. You know what I mean you’ve got kids growing, they’re going to need clothes and food.” Another group of women discussed their personal experiences with poverty. One female participant volunteers, “[I’d] consider a hand-out because I’m poor. My husband is college educated. I’m trying to go to school, and I have two children, nursing one of them.” These are two typical examples of how themes of children, family, poverty, and the needs of vulnerable populations emerged in the deliberation.

To make clear how we coded the discussions systematically, and to illustrate how the conditions shaped these word counts, consider the following two contrasting examples, one from the relatively gender-egalitarian condition of majority-female, majority rule, and one from the gender-inegalitarian condition of minority-female, majority rule. In the first example, the group consists of four women and one man and uses majority rule. A woman introduces the topic of children, using it to highlight the needs of children and the difficulties of those who care for them. A man then takes up the topic sympathetically.

In the second example, the group is composed of two women and three men and uses majority rule. A woman tries to initiate a discussion of her brother who has Down syndrome (where “brother” indicates the topic of family) and is twice interrupted by a man, who brings the discussion back to a more abstract topic. In this way, such groups give women’s distinctive topics much less attention. We have highlighted the words that our method counts as belonging to one of women’s distinctive topics:

Gender-egalitarian condition: Majority women, majority rule

0:09:01 |

Woman A: Well you just have a little baby that’s one thing. Try getting you know a single mom and two teenagers or [crosstalk] high and my fees are almost a thousand dollars a year to send my kids to school. You know what I mean it’s like— |

0:09:15 |

Woman B: I honestly have no idea. |

0:09:17 |

Man D: But, but we’re just saying like one child and let’s say he’s you know eighteen or sixteen or something so we’re in high school, one kid— |

0:09:24 |

Woman B: [interposing] And driving— |

0:09:26 |

Man D: —sixteen driving sure and I think that takes a lot more money than like one baby would or something ’cause that’s true it changes everything. |

In the previous exchange, issues of children and family take center stage, with both men and women contributing their views and personal experiences about the challenges of raising kids on limited income. In the next conversation, though, the special needs some families might face are completely marginalized, and the woman who attempts to raise them is interrupted, then ignored. She cannot even finish her sentence about her special needs brother.

Gender-inegalitarian condition: Minority women, majority rule

0:19:49 |

Woman C: [interposing] Like my brother has Down syndrome— |

0:19:49 |

Man E: [interposing] But what is our goal? Our goal is the overall— |

0:19:51 |

Woman C: [interposing] —he’s never going to make— |

0:19:51 |

Man E: —group’s effectiveness right? |

0:19:54 |

Woman A: We’re also still going for society, though. |

Man B: [interposing] Our group is to find an idea that we feel is most just for— |

|

0:19:56 |

Man D: is most just. |

0:19:57 |

Man B: —for society. |

0:19:59 |

Man E: So it’s not to maximize our efforts. |

0:20:00 |

Man B: No. It’s just to find a thing that we feel that is most just for society. |

0:20:04 |

Man D: You know, to find a balance between well we want to maximize but we also want to help. I mean there’s got to be a balance. We just find the best. |

0:20:09 |

Woman C: Right. |

0:20:09 |

Man B: Yeah. |

A third example also illustrates this point that men are more likely to discuss and validate the concerns of women when women have higher status in the group. In the example below, men outnumber the female speaker, but the group decides by unanimity. The woman introduces concerns about the welfare of parents and children, and a man in the group adopts similar language and validates her concerns.

Gender-egalitarian condition: Minority women, unanimous rule

These examples illustrate three notable exchanges, but our effort in counting words is to identify more systematic trends that occur across the experimental conditions. While our word count method has the virtues of simplicity and ease of systematic analysis, it cannot tell us what is being said about these categories. The biggest threat to the validity of our scheme is the possibility that a person mentions the category in order to articulate a position against assisting people in it. To rule out the possibility that speakers mention women’s distinctive topics unsympathetically, we classified each mention as sympathetic, neutral, or negative. The unit of analysis is the speaking turn containing a reference to a topic of distinctive concern to women (N = 1,926, which contains the entire set of “care” words we analyze below). For example, negative mentions include: “rob from the rich to give to the poor.” Examples of sympathetic phrases are: “whether the poor ever get help by anyone, that is not even raised here”; “if like the range is like 50,000 or whatever … then the poorer they don’t get anything. It’s kind of risky”; “I thought maximize the floor income was, that was my number one, help those who have the least.” We found that only 5.0% are negative. That is, mentions of the vulnerable or needy are rarely unsympathetic.10

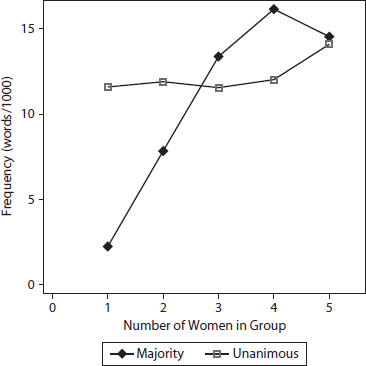

Do the conditions that affect the quantity of women’s participation in the group discussion also affect the content of their participation? The bottom line is “yes.” Women’s average Frequency of words referencing care issues varies considerably across these conditions. In chapter 5 we found that the condition that most disadvantages women’s floor time and influence is majority rule and minority women. Consistent with this finding, we now see that women’s average Frequency of care issues in this setting is 6.3 words per 1,000—about half the Frequency in any of the other settings.11 Conversely, the setting that stands out for producing the greatest Frequency of women’s references to care issues is the same setting where women’s influence and speaking are highest (nearly 15 per 1,000)—majority rule with majority women.12 Frequency is in between these two extremes for unanimous rule groups with minority or majority women (11 words per 1,000 in each of these two conditions).

These percentages represent substantial changes in the emphasis of the discussion. And when multiplied by the total number of women in the group, even small individual increases can significantly affect the number of times the concept is raised overall. We will see more clearly how meaningful this number of references is a bit further on, when we contrast it against the percentage of references devoted to topics that are not women’s distinctive concern.

We now turn to regression analysis, with the individual as the unit of analysis. We employ probit for Mention (since it is coded either 0 for no references or 1 for one or more references) and OLS for Frequency, with cluster robust standard errors.13 (Descriptives and coding for all variables are in the online appendix.) We use two models: a dummy variable model, containing a set of dummy variables representing each condition, and the same linear model we used in earlier chapters, containing a dummy variable for majority (1) versus unanimous (0) rule, a variable counting the number of women, and a variable that multiplies the two. We control on number of egalitarians in the group (as a count from 0 to 5), a dummy variable for experimental site, the person’s predeliberation egalitarianism, and (for Mention) the log of the person’s overall word count (see chapter appendix table A7.1 for details).14

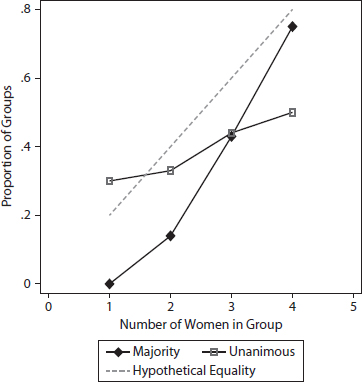

Figure 7.1 displays the predicted values for the topics we identified as of distinctive concern to women: the poor, children, family, and the “needy,” depicting the overall Frequency summed over the four care topics (see chapter appendix tables A7.1 and A7.2 for the models used to predict these results; Mention is presented in chapter appendix figure A7.1). If descriptive representation enhances substantive representation, then it will increase talk on women’s distinctive concerns. And that is what we find, but, as predicted, only under majority rule. As the number of women increases, so too does the percentage of women who reference care topics. The effect is quite large. As the number of women in the group increases from one to four, Frequency for the care topics increases by more than sevenfold, moving from 2.3 to 16.1 words per 1,000; for Mention, the average probability of referencing one of the care topics increases from 16% to 54%.15 This same upward trend can be seen for the summary measure of all care issues, and also each of its constituent parts is examined separately (see figure A7.2 in the appendix to this chapter). Moreover, there is no effect under unanimous rule on either Mention or Frequency. However, when women are the minority in their group, they are much more likely to mention care issues and to use them with greater frequency under unanimity rule than under majority rule.16

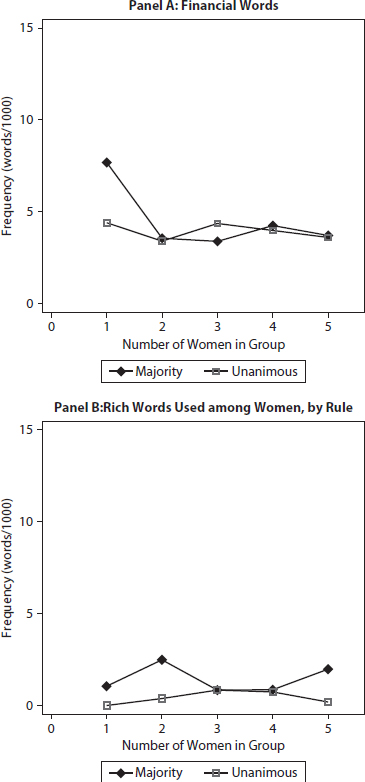

Notably, figure 7.2 shows that the increasing talk of care issues in figure 7.1 is not found for financial issues (panel A) or for the placebo category of “rich” (panel B). In fact, if anything, talk of financial issues declines as the number of women increases, though nearly all the decline occurs between groups with one woman and groups with two women; in groups with more than one woman, women’s talk of financial issues remains relatively constant and low.17

Recall that a second hypothesis from gender role theory predicts that women flourish in all-female settings. However, here, enclaves do not substantially increase care issue references above groups in which women predominate. Women raise care issues frequently in all-female groups under both decision rules, but not at a greater rate than in three-female or four-female groups.

Figure 7.2. Frequency of financial and rich words used among women, by rule (predicted values). Top: Financial words; Bottom: Rich words.

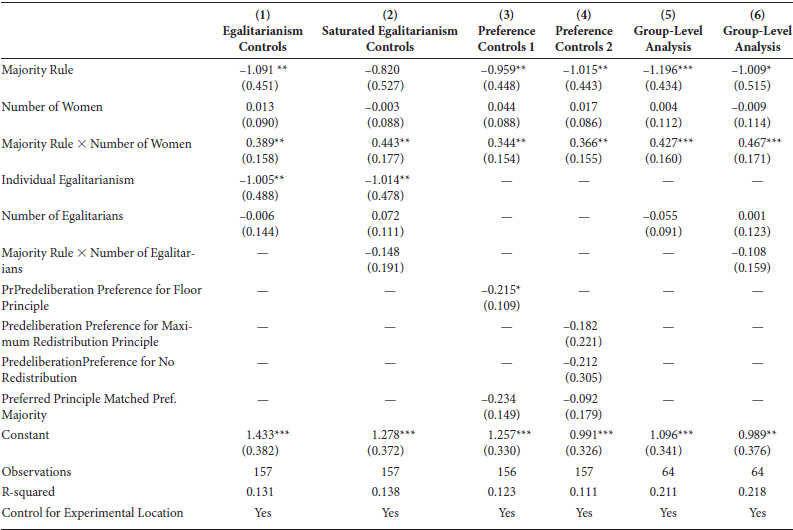

As a further test of our predicted interaction of rule and gender composition, we estimated our familiar linear model for the mixed-gender groups. Table 7.1 shows that the interaction term is significant, confirming that the effect of descriptive representation differs under the two rules. In addition to controlling for group and individual egalitarianism in all these models, we also ran each analysis omitting these controls, or replacing them with controls for predeliberation preferences and/or subjects’ age in a variety of different configurations, including a fully saturated model in which we interact the number of egalitarians in the group with the decision rule. The inclusion or exclusion of age, egalitarianism, or predeliberation preference controls has no effect on any of our key findings with respect to the use of care topics.18 The magnitude and standard error of the key interaction term is virtually unchanged no matter what set of controls we use.19 In addition, when we remove the individual-level controls and explore our interactive model at the group-level only (Models 5 and 6 of table 7.1), we again find the same, strong evidence of an interaction between decision rules and gender composition.20

When women are outnumbered, the paucity of care topics can be quite striking. Under majority rule, lone women never mention family, and only 11% mention children. Only 13% of minority women mention children at least once. In the unanimous condition, however, 46% of minority women mention children (with similar findings for family; p < 0.01 for children and family; all from raw means). When in the majority, 42% of women mention children in the majority-rule condition, compared with 47% under the unanimous condition. Women’s quiescence can reach the level of complete silence, making unanimous rule all the more important in protecting minority women’s voice.

We replicated these results using the TM method, which selects only the most frequently used words in the study. Among the most frequently used words are two that reference education (“school” and “education”). We reviewed the studies we noted above and education is in fact among the issues that women tend to emphasize in various settings, including choice of college majors (Carnevale, Strohl, and Melton 2011); as Crowder-Meyer found that women are “about seventy-five percent more likely than men to believe education is the most important problem facing the U.S.” (2007, 13). We grouped “school” and “education” with the care category, and find the same interaction pattern with these new words and with the overall care category generated by TM (see chapter appendix A for words and see chapter appendix table A7.3 for the linear interaction model using this alternate construction of care). Thus these two separate approaches—LIWC and TM—produce the same result. Women mention topics of distinctive concern to them less often in group settings where they are disempowered.

Table 7.1: Frequency of Care Issue Mentions among Women: Egalitarianism Controls vs. Preference Controls

Note: Standard errors in parentheses (cluster robust standard errors for individual-level analysis). Groups composed of five women excluded. *** p < 0.01, ** p < 0.05, * p < 0.10, two-tailed test.

WHEN DO WOMEN INTRODUCE TOPICS OF DISTINCTIVE CONCERN TO WOMEN?

How do care issues get on the agenda in the first place? An important measure of women’s exercise of voice is whether they introduce the topics of distinctive concern to them into the deliberation. Figure 7.3 depicts how often a woman was the first one within the group to mention a topic of specific concern to women, coded at the group level. The dotted line in figure 7.3 shows how often women would mention care topics first if there were no difference between men and women (for example, women would be first mentioners 40% of the time when they composed 40% of the group). When women are in the minority, the first mention of a care topic was made by a woman in only 6% of groups under majority rule, but in 31% of groups under unanimity rule (p < 0.04, one-tailed, raw means). The difference between rules disappears when women are the majority (53% under majority versus 47% under unanimity rule, n.s.).

Figure 7.3. First mention of care topic by women (raw means, by group). Note: The y-axis represents the portion of groups in which women mentioned care topics first.

Table 7.2 examines the effect of the conditions on the probability of first mention of care in an individual-level probit model with controls for individuals’ “care” Frequency, verbosity, egalitarianism, and on location and the number of egalitarians in the model.21 The interaction of rule and composition remains strong and significant. Thus both group- and individual-level analyses lead to the same conclusion: women talk more about the topics they prioritize and are more likely to introduce those topics in the first place in conditions that empower them by the combination of numbers and rule.

Table 7.2: Probability of First Mention of Care Category among Women

|

(1) |

(2) |

Majority Rule |

–1.620** |

–1.262 |

|

(0.761) |

(0.821) |

Number of Women |

–0.199 |

–0.223 |

|

(0.150) |

(0.155) |

Majority Rule × Number of Women |

0.478** |

0.570** |

|

(0.223) |

(0.241) |

Percent of Care Mentions |

0.053 |

0.047 |

|

(0.103) |

(0.112) |

Speaker’s Percent Talk |

1.610 |

1.555 |

|

(1.015) |

(0.994) |

Individual Egalitarianism |

–0.449 |

–0.517 |

|

(0.865) |

(0.864) |

Number of Egalitarians |

0.101 |

0.216 |

|

(0.109) |

(0.144) |

Majority Rule × Number of Egalitarians |

— |

–0.217 |

|

— |

(0.182) |

Constant |

–0.820 |

–1.005 |

|

(0.659) |

(0.660) |

Observations |

157 |

157 |

Pseudo R2 |

0.053 |

0.060 |

Control for Experimental Location |

Yes |

Yes |

Note: Entries are probit coefficients. The dependent variable is the probability that an individual woman will make the first mention of a word in one of the four care categories. Individual-level analysis. Cluster robust standard errors in parentheses. Women in all-female groups excluded. *** p < 0.01, ** p < 0.05, * p < 0.10, two-tailed test.

The pattern is familiar. Under majority rule, the average woman in the majority is the first to mention care issues much more often than the average minority woman; there is no such effect of gender composition under unanimity. The magnitudes are again striking: for example, no lone woman is the first to mention care issues under majority rule, but a lone woman produces the highest chance of mentions under unanimous rule, underscoring the importance of decision rule.

HOW DO WOMEN’S DISTINCTIVE ISSUES COMPARE TO MEN’S DISTINCTIVE ISSUES?

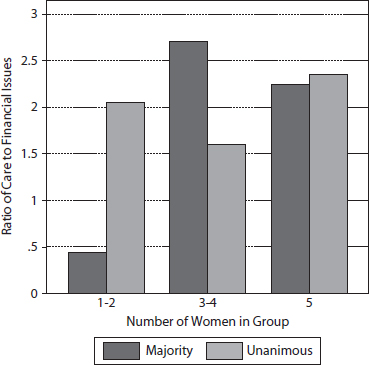

We can get a clearer picture of women’s substantive representation by examining the relative balance of care and financial topics across the conditions. We do this by computing the ratio of average Frequency of care topics to average Frequency of financial topics for each individual in the experiment.22 The ratios are shown in figure 7.4 (raw means by condition) and support our interaction hypothesis.23 Majority status matters under majority but not unanimous rule: the average woman’s ratio of care to financial topics increases under majority rule, from 0.44 as a minority to 2.7 as a majority (p < 0.01), but declines slightly and not significantly under unanimous rule (from 2.05 as a minority to 1.61 as a majority, p = 0.29). These numbers also show that unanimous rule helps women who are outnumbered by men (0.44 under majority rule and 2.05 under unanimous rule, p = 0.02). Finally, the interaction between gender composition and decision rule is significant, meaning that the effect of increased numbers is different under majority rule than under unanimity (p < 0.01).24 Numbers benefit women only under majority rule, while unanimous rule protects minority women’s voice.

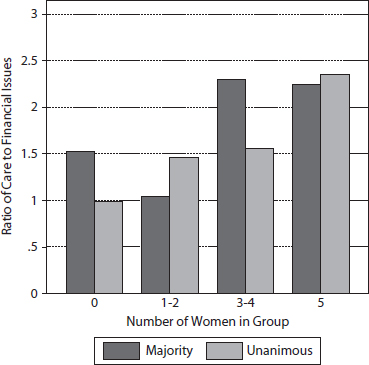

We have focused primarily on women since it is women’s voice that is at issue in the theoretical and political debates that prompt this study. Figure 7.5 displays predicted values for men (using the same model as above) and shows that the average man is also affected by women’s descriptive representation under majority rule, but by a more modest magnitude than the average woman: the ratio of care to financial Frequency increases from 1.19 (with female minorities) to 1.42 (with female majorities). Under unanimous rule, the ratio increase is similar, from 1.20 to 1.48. In addition, unanimous rule does not substantially elevate the average man’s relative emphasis on women’s priorities when women are a minority—unanimous rule protects minority women’s voice but does not empower women to influence men’s speech.25

Men are, however, affected by the experimental conditions with respect to the topic that is most distinctively women’s concern: children. Under majority rule with one woman present, only 19% of men raise the topic of children, versus 69% who mention salary-related issues. However, surrounded by four women, men’s focus reverses: 62% now mention children as compared to 50% who discuss salary.26 But the effects of gender composition do not extend to discussions of the poor or the needy (predicted probabilities from the dummy model using Mention, chapter appendix table A7.1). Overall, figure 7.5 shows evidence of movement in the direction of a higher ratio of care to financial issues, but the movement is modest and not statistically robust.

Finally, the overall substantive representation of women’s distinctive issues can also be measured by the average ratio for all participants, including both women and men. Figure 7.6 shows that when they are empowered by the combination of the rule and their numbers, women can move the overall focus of the group discussion. The ratio of care to financial Frequency goes up substantially—more than doubling—as women go from minority to majority, but only under majority rule, where it increases from 1.04 to 2.30 (p = 0.01, two-tailed).27 For unanimous rule the effect of gender composition on the group is much smaller, from 1.45 to 1.52, and not statistically significant.28 Women need the joint power of large numbers and a rule that favors large numbers to have the biggest effect on the terms of the group discussion. Unlike the finding on women’s talk and consistent with men’s talk, unanimous rule confers no statistically discernible benefits over majority rule in minority-female groups (the ratios increase from 1.04 under majority rule to 1.45 under unanimous rule).29 Despite their increased attention to issues of care, women’s small numbers make it difficult for them to affect the overall tenor of the discussion.

ARE WOMEN’S VOICES DISADVANTAGED RELATIVE TO MEN’S?

So far we have not asked if women’s voices are disadvantaged relative to men’s—that is, if a gender gap in voice exists, or how it changes with the conditions. We do so using the Mention measure, which can be interpreted as the chance that a given person refers to the issue and allows us to move the question from how much a person talks to how many people talk. We ask whether women are less likely to raise their distinctive concerns than men are to raise theirs in the conditions prevalent in the real world—majority rule and minority women. The answer is yes. In these conditions, women’s probability of mentioning care issues is 57%; men’s probability of mentioning financial issues is 81% (p < 0.03). Thus in most political settings there is a gender gap in voice. When women compose a majority under majority rule, the percentages reverse: 89% for women and care, versus 68% for men and financial, respectively (they differ at p < 0.04; see figure A7.3 in the appendix to this chapter for a graphical representation of the percentages in this paragraph).30 But that is not the only way to remedy women’s disadvantage. Leaving women as a minority but changing the decision rule from majority to unanimous also helps, raising women’s probability of mentioning care issues to 91% and lowering men’s probability of mentioning financial issues to 72% (in these groups, these percentages differ at p < 0.05). That is, women are severely disadvantaged relative to men as a minority under majority rule and heavily advantaged as a majority under majority rule or as a minority under unanimous rule.31 (As a majority under unanimous rule, there is virtually no gender gap and nearly each individual mentions their gender’s distinctive issues.)

We can see these patterns in the following example where a female participant introduces feminine issues, but the others do not take up the topic though they give them passing attention. The topic quickly shifts to the potential benefits of taxing the highest earners. The man shifts the topic from issues important to women (bold, underlined) with words connected to financial issues (bold, italicized).

Gender-inegalitarian condition: Minority women, majority rule

0:04:45 |

Woman D: It would be easy for you to think that way ‘cause that’s probably how it’s been for you but there’s a lot of people that don’t have the opportunities and so even though they may have had the ability if given opportunities they’ll never know and just get by. |

0:05:01 |

Man C: I mean I look at it more as we should let the top pull us up than the bottom pull us down.— |

0:05:05 |

Woman D: Hm. |

0:05:06 |

Man C: [interposing] And if you let people with the top keep doing their thing and doing what they can actually do and then, you know,— |

0:05:08 |

Woman D: Hm. |

0:05:09 |

Man C: [interposing] Yeah, give a little bit at the bottom but the more that they get unless they would take 10% if they’re earning say a million dollars that 10%— |

0:05:19 |

Woman D: Hm. |

0:05:20 |

Man C: [interposing] is a lot more than a hundred thousand’s 10% and whereas if it’s just like okay, you know, then if we set a range then why would I want to work ’cause if I’m making 50—and that’s the minimum, well cool— |

0:05:32 |

Woman, D: Uhuh. Yeah, I could see how that could happen. |

The regressions confirm the effect we can illustrate with qualitative examples. Both types of analysis show that in conditions of gender equality, women introduce women’s distinctive topics; when these topics are introduced, subsequent speakers take them up; and women tend to mention these topics to argue for generosity, help, or meeting a need. In conditions with high gender inequality these are less likely, and when a women’s distinctive topic is mentioned, it tends to die in the conversation.

DOES TALK OF WOMEN’S DISTINCTIVE ISSUES DECREASE WOMEN’S SATISFACTION AND PERCEIVED INFLUENCE?

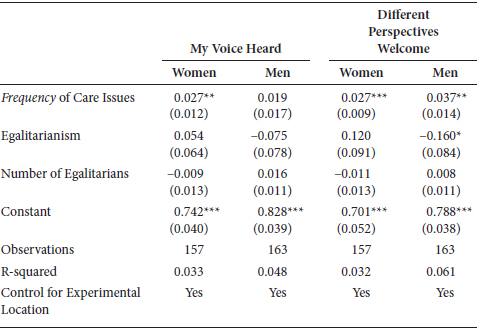

We can also ask how talk of women’s distinctive issues affects the way men and women think about their experience during discussion and about their influence in the group. How does the content of the discussion affect deliberators’ evaluations of the discussion and of each other? Recall that after the discussion, we asked a variety of questions about how each participant felt about their experiences. These questions include whether the participant felt his or her voice was heard and whether different perspectives were welcome. Response options were on a five-point scale ranging from “Strongly Disagree” (0) to “Strongly Agree” (1). Table 7.3 shows the effects of the person’s frequency of care issues on the person’s assessments, for men and women, respectively.

Table 7.3: Effects of Person’s Frequency of Care Issues on Evaluations of Group Functioning

Note: Individual-level analysis. Cluster robust standard errors in parentheses. The coefficient for Frequency of Care Issues shows the effect of a 1 percentage point increase in care issues as a percentage of all words spoken. Dependent variables are coded to span from 0 to 1. *** p < 0.01, ** p < 0.05, * p < 0.1, two-tailed test.

Although the effects are not large—no one left feeling extremely angry or upset—the results in table 7.3 show a number of meaningful consequences from the exercise of women’s voice. First, the experiences women have during discussion affect women’s perceptions that their voice was heard. The more they mention care issues, the more women felt that what they had to say had been heard during the deliberation.32 Mentioning care issues does not have this effect on men; though the coefficient is positive for men, it is smaller and not statistically significant.33 As we might expect from our discussion in chapter 3, men are less likely than women to rest their sense of efficacy on the substance or the dynamics of the conversation.

Furthermore, the more they talk about care issues, the more women tend to view discussion as airing different perspectives. And in this, they are joined by men. We did not expect men to react to their own focus on care issues, but they do. If anything, men shift even more than women with respect to the assessment that the discussion aired diverse views when care issues are an increased part of their own talk. When they speak to care issues, both genders feel better about the discussion as a whole, but only women’s sense of efficacy is clearly affected.34 We take this as evidence that women’s sense of confidence, competence, and efficacy in deliberation is more sensitive than men’s, and that it responds to women’s ability to articulate their distinctive issues.

One potential caveat about the results is that while mentioning women’s distinctive issues benefits women’s representation, it may also decrease women’s perceived influence in the eyes of other members of the group. If this were true, increasing women’s substantive representation by changing the agenda would not be as beneficial overall for women’s authority and thus their representation. However, we find that there is no association between a woman’s Frequency of care issues and her perceived influence after deliberation.35 Women’s overall substantive representation does not suffer from women’s voice.

THE DOG THAT DIDN’T BARK

We have been completely silent on one matter. We have said nothing about women’s own distinctive needs and interests as women. While we have spilled much printer ink (clicked many keyboard keys?) in the service of documenting and explaining women’s other-regarding motives and actions, what women want for themselves remains a mystery. In the discussions in our experiment, neither women nor men tended to raise the issue of gender directly. Specifically, our counts yield few references to “women” or “woman,” nor did we hear much talk of “men” or “man.” More importantly, the talk that did refer to these terms did not shift according to any meaningful pattern across our conditions. Settings that shift women’s status and influence, and that elicit more or less talk of issues of distinctive concern to women, do not produce more discussion of women themselves. At least not when the task at hand is not explicitly tied to women or to gender. It seems that when the decision is not about women specifically, women are not mentioned specifically.

When the topic is redistribution, women may not think readily about the needs of women, simply because that is not how redistribution is usually discussed in public discourse. However, that does not make it any less meaningful to discover that women do not regard themselves as a relevant group when considering who needs assistance or generosity. After all, households headed by single women are twice as likely as those headed by single men and over five times more likely than those headed by a couple to live in poverty.36 And yet despite the difficulties that these single women face in supporting their households, the word “women” is extremely scarce in our discussions of poverty, inequality, and redistribution. This absence is all the more striking considering that in some forums of public discourse, women’s well-being and economic conditions have been noted as highly relevant to general inequality and well-being.37

A likely reason for the silence on this topic is that the women of America seldom articulate their own interests or needs as women as part of the public agenda. Few women call themselves feminist, and women have little warmth for feminists (Huddy, Neely, and Lafay 2000). If one wants to predict support for abortion rights, either in the populace at large or among citizens active on a political issue, the last variable one should reach for is the person’s gender, and if one does select this predictor, prepare to encounter the opposite sign (Burns, Schlozman, and Verba 2001, 123–24). Burns and her colleagues, who took thorough stock of women’s participation on women’s issues, “were struck at how little activity—pro or con, by women or by men—is animated by concern about women’s issues” (Burns, Schlozman, and Verba 2001, 127). Under the ordinary circumstances of day-to-day political life, women bear little resemblance to the compatriots of Betty Friedan, Shirley Chisholm, or Gloria Steinem. Many of today’s young women might be hard-pressed to tell you who

Gloria Steinem is, and bra burning may be viewed as a quaint, vaguely funny, ancient ritual their grandmothers might have practiced. But age aside, women young and old prioritize the needs of others, of the collective, of the vulnerable, over their own—or so it is in politics.

CONCLUSION

In chapter 5, we saw that when we vary the number of women and the decision rule of deliberating groups we either produce a gender gap in participation during discussion and in ratings of a member’s influence, or we close that gap. Our starting point thus was the notion that composition and rule interact to shape women’s status in the group.

In this chapter we found that in the same conditions where women speak more and carry more perceived influence, women are also more likely to speak to their distinctive concerns. Not only do women speak less when they are minorities under majority rule, they also speak less to the concerns women tend to raise and act upon. In other words, a valuable set of perspectives and considerations is nearly entirely lost to the group in the setting where women’s standing is lowest. What is true of talk time is also true of the content of the talk: women are worst off in groups with few women and majority rule. To avoid the single most deleterious setting for women, avoid majority rule with few women.

Unanimous rule dampens, eliminates, and even reverses this deleterious effect of minority status for women. As we found with participation and influence, so it is with the agenda—when women are numerical minorities they are better off with unanimous rule, and as majorities, better off with majority rule.38 When women interact with men, large numbers tend to help women when they operate under norms that advantage large numbers.39

However, while unanimous rule provides a much-needed boost to women in the minority, the most effective setting for women’s agenda setting in interactions with men is majority rule with many women. That setting is where many aspects of women’s substantive representation come to fruition. That is, there are different types of substantive representation, and our findings indicate that the same setting that elevates one type tends to elevate the others. Majority rule with a large majority of women tends to:

• free women to introduce women’s distinctive issues into the agenda;

• maximize the average woman’s and women’s collective voice on women’s distinctive issues, including on the ratio of women’s to men’s issues;

• prompt men to adopt some aspects of the care agenda, but primarily with respect to discussion of children, and only when women form a supermajority; and

• increase the overall group voice for women’s distinctive issues and its emphasis on care over financial issues.

If one had to pick the one setting that yields the most forms of substantive representation for women, one should pick majority rule with many women.

But women’s enclaves emerge as another space that provides a high degree of substantive representation for women. Although these settings are not dramatically different from the empowering settings where women interact with men, they are worth noting as one more way that women can publicly speak to their distinctive concerns. Across both decision rules, these groups function much like the majority-rule groups with many women to elevate women’s talk of care.

Raising issues and topics that do not come up much otherwise is a crucial form of power, as theories of the second face of power have long noted (Bachrach and Baratz 1962; Gaventa 1982). Our findings shed light on one neglected reason why this form of power matters. It matters in particular by elevating the sense of empowerment that disadvantaged groups feel. We found that the more that women speak to women’s distinctive concerns, the more they tend to report that their voice was heard.

But the results here do not imply that women’s empowerment comes at a cost for the quality of deliberation. In fact, we found that both women and men tend to evaluate the overall discussion as more inclusive the more they speak to issues of care. The more one speaks about the needs of vulnerable populations, the more one tends to report that the discussion aired a variety of perspectives, and this holds as much or more for men as for women.

Beyond the impressions of the deliberators themselves, deliberation is better when all sides raise their distinctive perspectives more fully. For some theorists (Sanders 1997), a more complete telling of one’s side of the story means that deliberators voice their views in their own words. Our results show that women choose different words—words that are more closely tied to their set of distinctive concerns—when they are empowered. In the settings where their standing is greatest, the terms of discussion and debate shift—literally—in ways that are more friendly to considerations that tend to be important to women. This change in the content of the discourse, this increased ability for women to make their arguments on their own terms, is a meaningful mark of substantive representation as well as deliberative inclusion.

Our measures have important limits. One potential weakness of our analysis is that mention of a topic does not indicate a particular position on the left-right policy spectrum. We have three responses to this valid criticism. First, studies we reviewed suggest that women are both more likely to mention these topics when asked about their concerns and priorities, and likely to take a liberal position on these topics. Thus women tend to indicate that these populations are on their mind and to take a sympathetic position toward them—talking about them and sympathizing with them seem to go hand in hand. Second, we provided evidence that the mentions in our study are almost never negative. Third, the salience of a topic is itself an important type of substantive representation; in fact, as we noted above, some theorists argue that the presence of an issue on the agenda is the most important measure of political power (Bachrach and Baratz 1962; Gaventa 1982). The disagreement cannot come to light and no view on the issue can be aired if the topic remains off the agenda. To be sure, in groups where people mention women’s issues but women lack power, the outcome may not conform to women’s general preference for generosity to the vulnerable. Nevertheless, chapter 9 will show that the conditions where women speak to their distinctive topics on the whole tend to foster group decisions in line with women’s preference for generous aid to the needy. All this tells us that the way we have counted words is a useful way to analyze representation, especially since we accounted for the direction toward which these words lead.

Validation of these results comes from an experiment on “mock-jury” deliberation in a simulated sexual assault legal case featuring an adult who sexually assaults a six-year-old child (Golding et al. 2007). In keeping with the notion that women place a higher priority on protecting children than men do, women’s initial preference was to convict, men’s was to exonerate. However, this priority was much more likely to find expression in the deliberations of the majority-female groups than in the other groups. And in these same groups where women’s priority found greater voice, the individual votes and group verdict were much more likely to tilt toward that priority. Thus, as in our study, the groups where women articulated their priorities were the groups where the outcome was more in line with women’s preferences and women had more influence.

However, the key point of the study is that women’s voice in deliberative settings varies a great deal with the institutional setting. Studies of women’s representation in legislatures recognize the importance of institutional rules and norms among political elites (Carroll 2001; Grünenfelder and Bächtiger 2007). Our results suggest that rules and norms also shape interactions among citizens. These norms of communication affect men as well as women. They also produce quite different levels of conversational salience for the topics that tend to concern women. In these ways institutional settings can contribute to or detract from equal substantive representation, for as Mansbridge (1999) notes, descriptive representation can affect the quality of deliberation in political institutions by bringing in the commonly shared perspectives of the disadvantaged group. We have taken a step toward unpacking the black box of deliberation to show how, and when, descriptive representation matters for substantive representation.

The analysis in this chapter makes a number of contributions to the larger scholarly literature on gender and substantive representation. Although studies have documented that female representatives act on a distinctive set of concerns (for example, Carroll 2001; Kathlene 2001; Swers 2002), we are not aware of studies showing that women articulate different topics or words from similar men in public discussions (for excellent small-N studies, see Kathlene 1994 and Mattei 1998). That women tend to articulate a “different voice” is suggested by a number of studies of women in office; for example, Beck found that on the issue of local leaf collection, men tended to focus in their interview with her on financial implications and women on the needs of the vulnerable population in the town (Beck 2001, 57). Our results confirm but extend such findings to the world of ordinary citizens and do so in a way that makes clear that group-level factors are key determinants of the content of group discussion. Linking speech to predeliberation preferences also allows us to control on predeliberation egalitarianism and preferences over the group decision and thus isolate the effects of gender from the effects of these attitudes and preferences. Thus we can conclude that conditions that increase women’s talk of women’s distinctive topics do so by altering the gender dynamic specifically and not because they shift people regardless of gender. Our placebo tests further indicate that the shift occurs on women’s distinctive issues only and is not caused by nongendered conformity or general majority-induced dynamics. In addition, we are not aware of studies documenting that men adopt speech similar to women’s and do so as women’s influence rises.

We end with a note about why it matters that women bring their distinctive concerns to the group’s agenda. We have been discussing women’s agenda setting at a practical and concrete level, and for justifiable reasons. But women’s agenda setting matters at a more abstract level too. As the philosopher Fricker (2007) argues, a fundamental injustice is the disadvantage that social identity groups experience in defining the terms of discussion. For example, Fricker notes that a woman who experiences rape in a community that does not recognize the meaning of that term experiences a profound disempowerment because the injustice of the experience has no name, and without a name, there is no recognition and no understanding of the harm (2007, 6). Such a woman cannot possibly articulate her needs or perspectives in a discussion when she herself does not know that these are needs and perspectives, what they are, and how to describe them to others. Less dramatically, we can think of the needs of children, the homeless, the sick, the destitute, the victimized, and the infirm in similar terms. If no one names their problems, afflictions, needs, or perspectives, they do not exist. A community or a society cannot begin to address a problem that has no name or help a group viewed as irrelevant to the collective. What women do by raising their distinctive concerns is more than naming a problem; they are including marginalized or disadvantaged groups in the conception of “us.” To raise women’s distinctive issues is to situate vulnerable populations as a legitimate subject in the community as well as in the discussion. To do so is to participate equally in the practices through which shared social meanings are created, and this may be the highest form of influence.

We have been arguing that women’s probability of talking about women’s distinctive topics is shaped by conditions of gender equality. A missing piece in this argument is evidence that women talk in ways that reflect their lower status and influence in the group, and that men talk in ways that help them instantiate power. We next tackle this question.

1 Quoted in Hansen (1997, 73).

2 That is not to say that sex differences are immutable, or that environment plays a lesser role than genes. Rather, contemporary research underscores that genes find expression in large measure depending on environmental factors. As the biologist Arthur Arnold writes: “Although sex may be considered to be determined primarily biologically, our gender (i.e., the social perception and implications of our sex) is arguably equally or more important for our lives. Sex and gender differences are created by an intricate reciprocal interaction of numerous biological and environmental forces” (Arnold 2010). He further states: “Because sex-specific environmental forces correlate so strongly with sex-specific biological factors, it is often impossible to separate their effects, especially in humans. Environmental factors causing sex differences are often routinely excluded or ignored by biologists because they have been considered to be outside of the realm of biology. Nevertheless, such forces interact strongly with biological factors” (Arnold 2010).

3 Before we start, we want to note that defining “women’s distinctive issues” is by no means a straightforward task, and we do not wish to naturalize, essentialize, or reify gender stereotypes. Certainly, women’s concerns consist of vastly different things in different places, times, and for different subgroups. To take a particularly apt example, in one Indian province the provision of roads is deemed an issue of particular importance to men, while in another it is of much more concern for women (Chattopadhyay and Duflo 2004). We do not mean to minimize the importance of these definition problems. But we do think that we can learn a great deal by asking what concerns, perspectives, and priorities women, on average, would bring to the table, in a given place and time, if they could (see Carroll 2001, viii–xiv). We do not minimize the variety within women, which is indeed so large that it often dwarfs the difference between the sexes (Sapiro 2003). But we wish to see if there are central tendencies to women’s and men’s priorities and note places of difference between them. Everything we say here is intended to apply to the particular place and time at hand, and with the implicit understanding that much variety lurks within a gender category.

4 Women are also less supportive of military means and aggressive or coercive government policy (Conover and Sapiro 1993; Gilens 1988). Concurring results are found in Washington (2008, 312).

5 Legislatures are another arena where we see different priorities by gender. As women’s numbers grow, Swedish municipalities increased expenditure on child care (Svaleryd 2002). Comparative studies of legislatures across countries or across states in the United States find that as the number of women increases, women introduce more bills dealing with issues of women, children, and families relative to their male counterparts and to other women, accounting for the member’s party (Poggione 2004; Thomas 1991). Even accounting for party membership or the party in control of government, higher numbers of women lead to a rise in adoption and scope of maternity and child care leave policies (Kittilson 2008). Female US state house members place a higher priority than men do on these issues (Thomas and Welch 1991; Thomas 1994). Female legislators work to increase family assistance and strengthen child support enforcement (Besley and Case 2003).

6 We do not expect substantial differences by rule among the all-female groups because there we expect norms of inclusion regardless of rule.

7 We tried other more elaborate computer-based techniques that scale text, but LIWC most fully suited our aims for these analyses.

8 The words identified by the two methods overlap, suggesting that the words we chose a priori are among the most often used, but they differ enough that the similar results provide somewhat independent replication.

9 On average, women spoke approximately 700 words over 3.5 minutes, while men spoke approximately 800 words over 4 minutes, but as shown in chapter 5, averages vary significantly across the experimental conditions.

10 Neutral, 79.8%, and positive, 11.7%. The remaining 3.5% are false positives (word usages that did not turn out to be relevant to “care” issues; example: “that is a poor choice of words”). Also, among the entire sample, children, family, poor, and needy are more often mentioned by women than by men; salary is the reverse. Taxes, which groups are explicitly asked to discuss, are mentioned equally. The difference by gender (clustering by group) is significant for children, poor, and salary. However, these global gender differences are much less important to our argument than the changes across conditions.

11 These are raw means for all care issues summed, in mixed-gender groups. In all-female groups, Frequency is high across both rules (13.2 in unanimous and 14.6 in majority).

12 The difference from groups with minority women is significant at p < 0.01, two-tailed t-test. This result is very similar using Mention, which also shows a large, statistically significant difference across these conditions (p < 0.01). “Combined” for Mention means averages of Mention for the four topics.

13 We also employed OLS on Mention, finding similar results.

14 Women in our sample as in others are somewhat more egalitarian. We do not include an explicit control for word count when the DV is Frequency, as this measure already controls for overall verbosity in its denominator. Figure 7.1 displays the sum of the predicted values for the individual elements of the content categories from chapter appendix table A7.1. See chapter appendix table A7.2 for models in which the dependent variable is a summary measure of all care or financial categories. Both approaches yield essentially identical results.

15 Female enclaves are essentially the same as groups with four women. Chapter appendix figure A7.2 shows that the pattern of results described above is not limited to only one topic.

16 These differences are tested using raw data and a difference of proportions test for Mention (z = 3.12, p < 0.01, two-tailed) and a difference of means test for Frequency (t = 2.49, p = 0.02, two-tailed). Tests of predicted probabilities from linear models with controls (table 7.1 or table A7.1) confirm these results.

17 As seen in figure 7.2, and verified with TM. The effect of number of women (one to four) on financial issues using TM is -0.196, SE = 0.066, p = 0.004, controlling on site, including a majority rule dummy and rule × number of women, excluding all-female groups.

18 The overall correlation between gender and egalitarianism is moderate (0.36 for the group-level relationship between number of women and number of egalitarians). Our regression results for women are nearly identical if we control for liberalism instead of egalitarianism (see Mendelberg, Karpowitz, and Goedert forthcoming.).

19 For a graphical representation of the small difference made by including controls, see online appendix figure C7.1, which presents the predicted values for women in the majority-rule condition from models with and without controls. In addition, adding controls for age, education, or income (not shown) make no difference to the individual-level results in any of the models reported in the chapter.

20 The dependent variable in the group-level models is the average Frequency of care issues for women in the group. Adding controls to the group-level models for the number of participants above the median for age or income shows that those indicators have no effect. Adding a control for the number of college graduates also does not alter the effect of gender composition, but there is an additional effect of the number of college graduates on women’s references to care issues. Women who are college graduates tend to reference care issues more often than those who have not yet graduated from college in settings where women are empowered.

21 The DV is coded 1 if the person was the first to mention any of the care issues, 0 otherwise. This variable is always 1 for one member of each group, and 0 for all other members; some groups have no mentions of one or more care categories, but every group includes at least one mention of some care category. The results become stronger when controls for a person’s percent of care mentions and their overall percentage of group speech are omitted. Results are similar when excluding the controls for location/egalitarianism/number of egalitarians, and they remain robust when controls for age, education, and income are included.

22 This ratio is computed by dividing the individual’s average Frequency per care topic by his or her average Frequency per financial topic. We adjust for the number of topics in order to avoid the artificial inflation that could result from the fact that there are more care topics (four—children, family, poor, and needy) than financial topics (two—salary and taxes). Even with that adjustment, the magnitude of this ratio is largely a function of the unequal number of possible words in the care and financial categories. Thus its absolute magnitude does not imply a general female advantage or disadvantage. If an individual made no references to financial topics, the ratio is undefined and not included in the analysis. When we include these individuals by assigning them a very low financial Frequency and imputing the ratio, the results are very similar to the patterns we see in the figures. We do not include these imputed values in our analyses, however, because of the inherent uncertainty about exactly what the assigned financial Frequency should be. Small differences in the assigned value can make a large difference in the ratio.

23 We combine groups in which women are a minority (one- and two-women groups) and groups with a majority of women (three- and four-women groups) to simplify the presentation of results and avoid the problem of small N in groups with a single woman.

24 All tests are two-tailed and are computed using predicted values from a regression model with controls. We regress the ratio of care to financial topics on a dummy variable for majority rule, a dummy variable for whether the group had a majority of women, and the interaction between the two; models include controls for egalitarianism, the number of egalitarians in the group, the interaction between rule and the number of egalitarians, and experimental location. We predict values from the model and conduct a formal Wald test of the difference between the predicted values.

25 The figure also appears to show a difference across rule for male enclaves, but this difference is driven entirely by two men in one group whose ratio measures are more than three standard deviations above the mean for the sample. In the absence of those two outliers, the ratio for male enclaves is identical across rule and low.

26 These are raw means; from the model with controls (Mention, chapter appendix table A7.1), we can see that the increase in men’s propensity to mention children is statistically significant (p = 0.01), but it is only when women are a supermajority under majority rule that men mention this most stereotypically feminine topic more often.

27 The formal test of significance is the same as described above, but the models include all participants in the sample.

28 The difference-in-differences in the effect of gender composition under majority, as opposed to unanimous, rule is significant at p = 0.03 (two-tailed).

29 Under unanimity, the group’s overall ratio of care to financial Frequency rises slightly as the number of women in the group increases. This increase does not contradict our hypotheses, however, because the average female frequency does not rise under unanimous rule.

30 These are raw means; the same relative effects obtain from predicted probabilities for Mention using controls for locations, egalitarianism, and log word count.

31 The advantage minority women receive from unanimous rule does not mean that the overall ratio of care to financial issues changes dramatically, in part because where women are outnumbered they receive a much lower weight in the group average.

32 Results are robust to a variety of different controls, including liberalism, age, education, and income (not shown).

33 Nor do we find that mentioning financial issues has any effect on men’s efficacy. Substituting financial issues for care issues into the results for men in the second column of table 7.3, we find no statistically significant relationship (p = 0.58, two-tailed).