CHAPTER 8

Unpacking the Black Box of Interaction

Powerlessness and silence go together.

—MARGARET ATWOOD1

PEOPLE DELIBERATE IN ORDER TO exchange words, and the words they choose tell us what the discussion is about and in what direction people’s preferences are heading. But speech is also a fundamental form of action. And so, the form that speech takes matters too. We already examined one form of speech—how much, and how often, people speak. We found that women speak less than men in the conditions that simulate most settings of public discussions. In these settings, women are a numerical minority, and there is no unanimous rule, and thus, nothing to elevate their participation in the discussion. As we saw, the more a person speaks, the more influence others attribute to him or her. Speaking provides an opportunity to establish authority—that is, it elevates one’s standing as a valuable member of the group. One of the functions of the act of speech is to instantiate power or status.

Here we explore one more way that a person can instantiate power through speech. We examine interruptions of other speakers and the responses to those interruptions. The way in which participants interact while speaking may enhance or undermine women’s status in deliberation. Gendered roles and expectations construct women’s speech as less authoritative to begin with. But the way that women’s speech is received can reinforce women’s lower status in the group and their authority deficit in the deliberation (Kathlene 1994; Mattei 1998). Our argument throughout the book is that the rules of interaction and the gender composition of the deliberating body jointly affect the degree to which speech elevates or depresses women’s authority. In this chapter we home in on the nature of interaction between speakers to illuminate how gender affects women’s relative authority—that is, their symbolic representation in discussion. As ever, we ask how the group’s rule and gender composition shape the nature of interaction and ultimately, women’s representation.

However, women’s authority may derive not only from power but also from warmth. Speech is not only a means to power, it can also establish social connection and solidarity (Tannen 1993).2 Social interaction is a crucial means for creating a sense of warmth and personal acceptance. Talk can communicate approval of the other person’s speech and positive regard for that person. Thus speech can be a form not only of instrumental cooperation but also of personal affirmation. The more one interrupts another in a positive way, the more support one is expressing for the speaker. The more supportive interruptions members provide for each other, the stronger the norm of “niceness” in the group (see Lawler 2003). It is a norm that could create a more inclusive dynamic that invites women’s participation. An important condition for women’s full participation and representation, we argue, is the group’s culture of warmth and affirmation.

Here we examine interruptions as a means of achieving each of these functions of speech, in turn. We ask whether women’s descriptive representation and the decision rule influence women’s relative power and the level of social solidarity in the group by shaping the use of interruptions.

A key distinction we pursue is between negative and positive interruptions (following Smith-Lovin and Brody 1989; see Li 2001). Negative interruptions are a power play. They represent one member’s attempt to seize the floor from another to express opposition or deprecation. We can see examples of how these negative dynamics operate in Beck’s (2001) case study of a suburban town council, where female council members experienced meetings in a more negative way than men, sometimes finding themselves “publicly demeaned” by male colleagues when they tried to express their views (Beck 2001, 59). Beck finds a common pattern in which women are more likely than men to “hold back” from expressing their views in response to the hostility they receive. As a female town council member told Beck during an interview: “Nobody hears me” (2001, 59). Negative interruptions are a way of asserting power and conflict—and even disrespect. In this sense, they may negatively affect women in particular.

Positive interruptions also represent power, but not of the negative kind. They are a way of collaborating, cooperating, and supporting the original speaker without detracting from that speaker’s effectiveness. In fact, positive interruptions can be a way to enhance the power and authority of both speakers.

Positive interruptions also play a crucial role in prompting speakers to believe that the audience is listening to them. When a speaker receives many positive interruptions they have instantaneous reinforcement in the form of agreement. The positive attention of other members may thus be important, perhaps especially to women’s choice to exercise their voice. One way that speakers can communicate this attention is to offer positive interjections.

Positive interruptions are also a way to establish rapport and bonds of fellow feeling. At the group level, many negative interruptions create an atmosphere of conflict and negativity; many positive interruptions create one of consensus and solidarity. If women are sensitive to the level of warmth and connection around them, then groups that exhibit more positive interjections may elevate that connection, and therefore increase women’s participation in discussion.

We ask whether the conditions that promote more gender equality in speech participation also exhibit a pattern of high power for women and high solidarity in the group. We ask a set of questions about power. In settings where we expect gender equality, do we see women receiving fewer negative interruptions? Do we see women receiving more positive interruptions? Do women who receive negative interruptions lose authority? We also ask a set of questions about solidarity. Are women more likely to use positive interruptions when there are many women—that is, are positive interruptions one of the consequences of creating predominantly female settings? Put differently, do predominantly female settings create higher levels of group warmth and affirmation?

THE MEANING OF INTERRUPTIONS

Status

The act of speaking provides an opportunity to establish authority and status as a valuable member of the group, but the group’s reaction is what affords the speaker this status. Interruptions are a communication signal. People signal their own and others’ status through their use of such communication cues, and they glean status from others’ signals (Ridgeway et al. 1985). Individuals independently verified as, or made to be, the more dominant or confident members of a conversation use a constellation of verbal forms that signal their higher status: they speak more; they speak earlier; they may initiate and complete more negative interruptions during a discussion, especially regarding a conflict; and they may issue fewer positive interruptions to their subordinates than subordinates issue to them (Dovidio et al. 1988; Johnson 1994; Kollock, Blumstein, and Schwartz 1985; Ng et al. 1995). Interruptions are correlated with volubility but carry a clearer signal of individual agency than volubility, which may indicate pure sociability (but see Tannen 1993). And they may have a particularly negative, silencing effect on lower-status groups, since those groups’ authority is fragile, and disagreements they may direct at high-status members tend to be countered with aggressive reactions or backlash (Ridgeway and Johnson 1990; Rudman and Glick 2001). Differences in patterns of interruptions are thus an indicator of, and reinforce, status inequality in conversation.

Because men have more authority than women do in society, they tend to use communication acts that symbolize high status, while women tend to employ those that mark low status (Dovidio et al. 1988; Lakoff 1975; Wood and Karten 1986; Ridgeway and Smith-Lovin 1999). A meta-analysis of forty-three studies confirms that interruptions conform to a pattern of gender hierarchy (Anderson and Leaper 1998); men tend to negatively interrupt more than women, especially in groups. Other studies confirm that men issue negative interruptions more often and positive interruptions less often than women, and talk longer (Aries 1976; Carli 1990; Kathlene 1994; Mulac et al. 1986; Mulac et al. 1988; Zimmerman and West 1975; but see James and Clarke 1993). Moreover, because women lose influence when they act too assertively, and may intuit this fact, women may be more likely than men to interpret disagreements they receive as a negative signal of their authority (Ridgeway 1982). Anderson and Leaper also found that women are three times more likely than men to yield when negatively interrupted in a group discussion on a gender-neutral task (1998; see also Smith-Lovin and Brody 1989). Gender differences of this kind are sharpest when the task involves a domain considered masculine (Karakowsky and Siegel 1999; Leaper and Ayers 2007). Politics is such a domain; women are viewed, and view themselves, as less confident and expert about politics, regardless of their actual level of expertise (Fox and Lawless 2011; Kanthak and Krause 2010; Mendez and Osborn 2010). Because women are more likely to enter a formal discussion of politics with a lower sense of authority, they may be more subject to and more affected by interruptions.

Social Rapport

Positive interjections can be a form not only of instrumental cooperation and agreement but also of warm affirmation of and rapport with others. Because they enter with less authority, women may be especially affected by a lack of affirmation, and thus by an absence of positive interruptions. Women sometimes complain that when they do speak, people don’t listen. As a woman who participated in a grassroots deliberative reform said to one scholar: “I went to three or four meetings … No one ever listened to my suggestions. They were uninterested” (Britt 1993, cited in Agarwal 1997, cited in Cornwall 2003). The same refrain is clear in a quote from a middle-aged female doctor interviewed by a journalist about her service on charitable committees. The doctor summed it up this way: “You get your cues right away. I will make comments about things, but it seems that no one hears me or no one agrees with me. And then I clam up” (emphasis ours).3 The absence of positive acknowledgment may signal to the speaker that their speech lacks value. As one interviewee told Mansbridge after a town meeting, “if you don’t say what they want to hear you’re not even acknowledged” (1983, 69); that is, lack of acknowledgement may be taken as indirect negativity toward the speaker as a group member, not just toward the specific content of their speech, and have a depressive effect. The positive attention of other members may thus be important, perhaps especially to women. One way that speakers can communicate this attention is to offer positive interjections, and these may have a stronger effect on women’s perceived influence than on men’s.

THE EFFECT OF NUMBERS ON INTERRUPTIONS

Only a handful of studies have examined the effect of group gender composition on interruptions, and they are limited by small group N and inconsistent findings. One study assigned university students to a six-member work group and found that majority-male groups engaged in more negative interruptions than other groups (Karakowsky, McBey, and Miller 2004). Similarly, Aries, Gold, and Weigel (1983) found that dominant-personality women interrupt negatively when interacting in all-female groups but not in mixed-gender groups. Another controlled study, however, found only limited composition effects (Smith-Lovin and Brody 1989). These studies use only between twenty and thirty-six groups.

Observational studies of political settings are also few and also involve a very small number of groups, lacking the ability to contrast across compositions. They do, however, tend to find that men use negative interruptions especially against women and that this correlates with other indicators of women’s lower status in the discussion setting (see especially the pioneering work of Kathlene 1994). Laura Mattei (1998) conducted the most in-depth analysis of language patterns in her study of female and male witnesses testifying before the all-male Senate Judiciary Committee on the nomination of David Souter to the Supreme Court. She found that relative to male witnesses, women were given less speaking time, experienced proportionately more hostile interruptions, were asked more challenging questions, were asked to bolster their testimony with more evidence, and were denied the floor when they attempted to interrupt. This pattern obtained for Democratic and Republican senators (all male). Female witnesses interrupted the senators back, but at a rate of one given to three received, while male witnesses, by contrast, responded at a rate of approximately one to one (Mattei 1998, 451). Finally, when men interrupted senators, they were given the floor to continue more often than women. In other words, in heavily masculine settings, men may use negative interruptions to assert their authority and to detract from women’s. Again, however, these conclusions are highly uncertain, because they are based on very small samples.

As we noted, interruptions fulfill two distinct functions, and power is only one of them; the other is social solidarity and interpersonal support (Bales 1970; Tannen 1993). Women tend to perform this function more than men, but gender composition matters, as women do so especially in interacting with other women. As we discussed extensively in chapter 3, women are more likely to express emotion when talking to other women than to men. Men are least likely to do so when interacting with men (Aries 1976; Carli 1989, 1990; Piliavin and Martin 1978). Mixed-gender groups pull each gender toward the middle. Thus descriptive representation may elevate the rate of positive and depress the rate of negative interruptions of female speakers.

The general theory revolves around the notion that gender roles produce gendered subcultures of talk and interaction (Tannen 1990). These subcultures are learned in grade school and developed in sex-segregated playgroups. Girls’ groups entail actions that grease the social wheels and emphasize cooperation and solidarity; hence, they are more expressive, less directive, and less overtly conflictual. Boys’ groups entail actions that signal individual agency, including issuing directives and joking at others’ expense (Maltz and Borker 1982). Consequently, as Cathryn Johnson puts it, “women nurture conversation to keep it going by obeying the rules of polite interaction, while men more often dominate the conversation and violate the rules of turn-taking without repercussion” (1994, 124). Groups composed predominantly of women implicitly follow the feminine style of interaction; those with many men tend to follow the masculine style.

DECISION RULE AND INTERRUPTIONS

As we noted in chapter 3, however, the extent to which gender inequality exists in speech acts, whether that act involves speaking at length or issuing interruptions, depends on the group’s procedures. Yet none of the studies we have just reviewed investigated a group’s rules or process norms. No study examined the effect of rules on the authoritative use of particular speech acts such as interruptions. As we argued in earlier chapters, the level of gender inequality in speech acts depends on the group’s procedures, specifically, the group’s decision rule, which operates jointly with gender composition.

Decision rules can create norms of decision making that apply to the deliberation preceding the decision. These norms may either override or boost the effects of gender on authority. Specifically, under unanimous rule, everyone must agree, and this expectation in turn creates norms of consensus, cooperation, and mutual respect. By implication, when each person matters, every voice is given adequate respect, even when that voice comes from women. The consensual norm created by unanimous rule may override the expectation of deference with which women tend to enter the discussion, and this benefits women when they are few. Consistent with this notion, in chapter 5 we reported that women’s floor time equals men’s when women are few and the group is instructed to use unanimous rule. Consequently, when women are few, we should see that the number of negative interruptions directed at women declines, and positive interruptions increase, under unanimous rule relative to majority rule.

However, unanimous rule does not create inviting dynamics across the board. As we reported in chapter 5, when women predominate, men are more talkative and are perceived as more influential relative to groups with few women and unanimous rule and to groups with many women and majority rule. We may find that the inclusive dynamic that women experience under unanimous rule applies only when women are the minority. We hypothesize that unanimous rule decreases negative interjections and increases positive interruptions toward women only when women are few.

Finally, as we argued in chapter 5, majority rule can create a dynamic of conflict and individual agency. We hypothesize that majority rule creates a high level of gender inequality in interruptions when women are few and thus occupy a low status. This may produce conditions where men engage in assertive speech acts, and where women have difficulty in taking and retaining the floor. Specifically, under majority rule with few women, relative to the other combinations of numbers and rule, we may see high levels of negative interruptions directed by men at women, and women may receive fewer positive interruptions.

MEASURING INTERRUPTIONS

We operationalize an interruption as an overlap in two speakers’ words that lasts at least 0.5 seconds, in which the first speaker spoke for at least 1.5 seconds, and the interrupting speaker spoke for at least one second.4 That is, the speaker must clearly hold the floor, and a second speaker clearly attempts to take the floor. Our software classified each speaking turn as an interruption turn based on these criteria. We then checked these interruptions by human coding.5

We defined interruptions as positive, negative, or neutral, following established definitions and building on Stromer-Galley’s coding (Johnson 1994; Leaper and Ayers 2007; Stromer-Galley 2007).6 These scholars define a positive interruption as supporting, agreeing with, or adding to the first speaker’s comment. Positive interruptions are a way of supporting the original speaker without detracting from that speaker’s effectiveness. Accordingly, we defined a positive interruption as either: (a) expressing solidarity with, affection, or support for the speaker or the speech, or (b) an interruption that completes the prior speaker’s thought in the same direction without disagreement or contradiction. Positive interruptions often begin with “I agree,” “yeah,” and so on. See online appendix E for coding details.

Negative interruptions are a power play. They represent one member’s attempt to seize the floor from another to express opposition or deprecation. A negative interruption disagrees, raises an objection, or completely changes the topic. A negative interruption may begin with phrases such as “well,” “but,” “however,” “not,” “I sort of disagree,” “I’m not sure about that,” or “I don’t know.” Not all negative starts are a negative comment, however. It is negative if it changes the topic without expressing understanding of the previous turn; does not use acknowledgment cues; or does not refer to the prior turn in any way, implicit or explicit.7

We also coded the interruption as elaborated or unelaborated. We defined elaboration as explaining one’s meaning. For positive interruptions, this entails adding content rather than simply echoing what the current speaker is saying. For negative interruptions, this means giving reasons for one’s disagreement. This is a measure of direct engagement by one speaker of another and reflects a measure of quality of deliberation. But it is also a measure of power. A negative interruption that is not elaborated represents a form of dominance behavior; conversely, a positive interruption that is not elaborated represents pure support for the speaker, and thus anchors the other end of the conflict-support continuum.8

For reliability, one coder coded all the discussions, and another coder independently coded 248 interruptions, 10% of the total. The percent agreements and Krippendorff’s alphas (in parentheses) are as follows: for positive, negative, and neutral interruptions: 83% (0.65), 79% (0.53), and 88% (0.43). For elaborations: 75% (0.50). The alphas are lower than desirable, but the standards in the literature come from text that is much more orderly and clear, such as interviews, speeches, or structured forums where speakers take clearly delineated turns and attend to grammar, which makes positive or negative content much easier to discern (Fay et al. 2000). We view these alphas as satisfactory considering the challenges of coding five-member informal interactions where turns are sometimes not clear and grammar is often murky. We note that the effects on these measures are no less trustworthy as a consequence of lower alphas; in fact, the effects must be powerful in order to cut through the noise of these measures.

For the whole sample, the average group’s positive interruptions are the most numerous, negative ones less so, and neutral interruptions are very few (see chapter appendix figure A8.1). Elaborations are much more likely for negative than positive interruptions, but summed across the valences they are fairly common in the average group (when pooling positive, negative, and neutral, the average number of elaborations per group is 19.5). However, we are concerned with variations across conditions and by gender, as we will explain.

We create two measures of interruptions. One is the negative proportion of all interruptions received.9 This measure holds constant the act of interrupting to focus on the balance of negativity and positivity of the interruption. It has the virtue of not conflating the likelihood of speaking or even of interrupting with the tenor of the interruption. Also, neutral interruptions are very few and have a lower coding reliability, and this measure sets them aside. As a second measure, we use the proportion of the person’s total speaking turns that were interrupted.10 We use separate measures for the negatively and positively interrupted proportion of the speaker’s speaking turns.11 This measure is not as clean as our first measure, but it includes individuals with zero interruptions received, while the first measure omits them.

We must guard against the possibility that the interrupting behavior of men (or of women) changes as the number of men (or women) changes simply because there are more men (or women) who could issue interruptions. To account for this spuriousness, we constructed our interruption measures by calculating the average behavior of the interrupters of each interrupted person. Thus when we ask if men increase the interruptions they issue to women across the conditions, for example, we are looking at the average interruptions males issued to each female.

Consistent with the previous chapters, our statistical strategy is to use OLS regression with robust clustered standard errors to account for the interdependence of observations within the deliberating group. We control on location, the interrupted person’s egalitarianism, and the number of egalitarians in the group, so that we can get at the pure effect of gender and gender composition rather than of political attitudes that correlate with gender but that are more peripheral to it (Huddy, Cassese, and Lizotte 2008; Sidanius and Pratto 1999). As needed we add controls for the quantity of the person’s speech—typically, the speaker’s number of speaking turns. Where the dependent variable is skewed and concentrated at zero, we replicate the main results with alternative estimators, typically Tobit (see online appendix C8.iii). We also replicate the main results with a fully saturated control model that includes a term for the interaction of decision rule and number of egalitarians (see online appendix C8.iv). That interaction term is never close to statistically significant, while the main and interactive effects of number of women remain fairly steady. We also find similar results when we replace egalitarianism and number of egalitarians with liberalism and number of liberals (see online appendix C8.v). Finally, demographic controls for age, education, and income never change our basic findings, either when we control for individual-level attributes or how those attributes are aggregated within the group.

THE BALANCE OF NEGATIVITY

We begin with our first measure of authority in speech, the negative proportion of interruptions received.

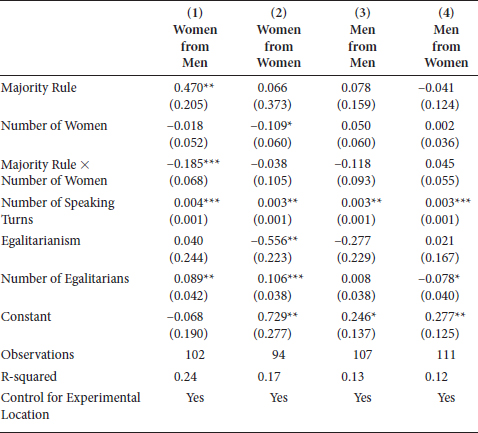

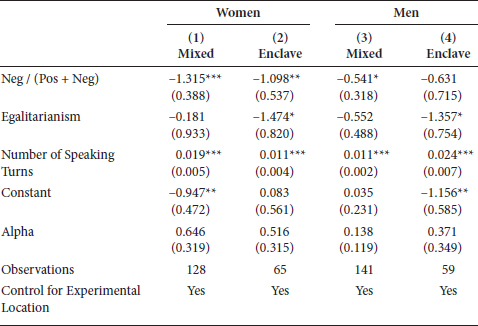

Table 8.1 displays the results of an OLS regression with the controls listed above as well as a control for the interruptee’s number of speaking turns, for mixed-gender groups, since we expect rule to matter more consistently when women interact with men. We estimate the effects of the conditions separately for each gender combination in the interruption dyad: women interrupted by men, women by women, men by men, and men by women. The first column shows that women are more likely to be negatively interrupted by men as a minority under majority rule than as a minority under unanimous rule. The coefficient on majority rule is positive, and predicted values from the model show that the difference across rules is significant at p < 0.05, two-tailed, for groups with one woman. Unanimous rule thus protects women when they are few, but this effect of rule erodes as women’s numbers increase (the negative interaction term for majority rule and gender composition). Put differently, numbers help women only under majority rule, and rule helps women only when they are few.

Table 8.1: Negative Proportion of Men’s and Women’s Interruptions Received, Separately by Male and Female Interrupters, Mixed-Gender Groups Only

Note: Dependent variable for all models is the proportion of received interruptions that were negative. Individual-level analysis. Cluster robust standard errors in parentheses. *** p < 0.01, ** p < 0.05, * p < 0.10, two-tailed test.

Figure 8.1 displays predicted values from this regression (holding all other variables at their observed values). When women receive an interruption from men, that interruption is much less likely to be negative than positive as their numbers grow, but only under majority rule. The magnitude of the effect of composition under majority rule is quite large: negative comments make up anywhere from approximately 70% (at worst) to just over 10% (at best) of the interruptions women receive from men. Gender composition shifts the tone of men’s direct engagement with women from clearly negative to highly positive. But it does so only under majority rule. Women do not enjoy the power of numbers under unanimous rule; under that rule, composition makes no difference. Finally, unanimous rule does help women in the minority relative to majority rule.

Figure 8.1. Negative proportion of negative and positive interruptions received by women from men, mixed groups only.

Some illustrative examples can give a flavor for how these patterns of interaction play out. In a majority-rule group with only two women, for example, one participant begins by acknowledging that he has spoken too much and tries to offer the floor to a woman. But almost immediately, he jumps back in, interrupting the woman repeatedly.

Gender-inegalitarian condition: Minority women, majority rule

00:04:44 |

Man E: Yeah, go ahead, I talk too much. |

00:04:46 |

Woman D: [interposing] Maybe it doesn’t make a point to talk about an option we don’t have, but it still seems that, as a version— |

00:04:54 |

Man E: That’s a good point. My only problem with one is, you generate a big group of people with almost the same income. |

00:05:02 |

Woman D: Yeah, which isn’t necessarily good because you never— |

00:05:04 |

Man E: [interposing] That’s my only problem. |

00:05:05 |

Woman D: Yeah there’s no— |

Man E: [interposing] Then you also somehow also eliminate the idea of the competition as well, right? |

|

00:05:12 |

Man, C: With setting a floor constraint, my problem with that is … |

Participant C goes on to speak for nearly a minute without interruption. Thus Participant D’s repeated, polite attempts to gain the floor—and to offer positive reinforcement to her conversation partner—are ultimately unsuccessful. She cannot utter a full sentence without interruptions from the men in the room, who are focused on “their problems” with the principles they are considering.

Contrast the dynamic in that majority-rule group with what happens in a unanimous-rule group with only one woman. In this group, the group members engage in a series of positive interruptions, each of which reinforces what the previous person has said.

Gender-egalitarian condition: Minority women, unanimous rule

00:12:21 |

Man D: Yeah. That’s what—I agree with whoever said—I can’t remember who said it, but to choose between the four is kind of hard, because it’s somewhat like—from what we’re talking about, we need, like, a middle between no taxes and then some kind of floor constraint, but with some provision of saying, like, there’d be a way to decide who— |

00:12:41 |

Woman E: Who gets the aid and who doesn’t. |

00:12:41 |

Man D: [interposing] Who gets—yeah, exactly. Depending upon— |

00:12:42 |

Woman E: [interposing] That’s what we need. |

00:12:43 |

Man B: [interposing] Yeah. |

00:12:45 |

Man D: We could make that. Can we? |

00:12:47 |

Woman E: [to moderator] Are we allowed to make our own options? |

[Laughter]

The dynamic could not be more different from what occurred in the majority-rule condition. The group laughs and jokes together, and the lone woman in the group repeatedly receives positive reinforcement about the points she is attempting to make. The sense of group solidarity is palpable, and Participant E is a full participant, sometimes finishing the thoughts of the men in the room and even ending this exchange by asking a question on behalf of the other group members.

So in conditions that give women the power of numbers or that protect them when they are few, women fare better. These settings serve to protect women by curtailing men’s dominant speech forms. This protection is clearly needed, as can be seen by the high level of men’s negativity toward women in the condition where women’s status is lowest—when women are a small numerical minority under majority rule. Unanimous rule protects minority women from this high negativity, though women do best as a majority under majority rule.

The effects apply only to men’s interruptions of women. Women direct a somewhat lower negative proportion of interruptions at other women as their numbers in mixed-gender groups grow, but this is unaffected by rule (table 8.1, column 2).12 Finally, the negativity men experienced is unaffected by the conditions (columns 3 and 4).13 Neither men nor women alter their behavior toward men as men’s proportion shrinks. (Figure A8.2 in this chapter’s appendix shows the same patterns with the raw proportions.)

These results represent an important validation of our argument that the mechanism accounting for women’s participation and representation in group discussion is women’s status. And that status is driven by men’s behavior toward women—not their behavior toward people, and not people’s behavior toward women, but specifically, men’s behavior toward women. Men take a dominant posture toward women in the conditions where we expect women to have low status, and by the same token, men undergo a drastic change when women’s status improves—they become far less aggressive toward them.

The composition and the procedures of deliberation jointly shape women’s authority during deliberation. Where women’s status is lowest—under majority rule and few women—over two-thirds of the interruptions women receive from men are negative. Where women’s status is likely to be highest—as majorities under majority rule—that proportion more than reverses, and over 80% of the interruptions they experience from men are positive. Men’s experience does not shift; only women’s does. And only men’s interruptions of women undergo this shift. What the conditions of deliberation do, then, is to shift men’s displays of power toward an affirmation of women. That is, interruptions appear to function as an indicator of women’s shifting status in the group, and men significantly affect that status.

POSITIVE OR NEGATIVE?

Are these patterns a result of a wave of negative interruptions, or of a steep decline in the number of positive interruptions, or both? We examine the proportion of the person’s speaking turns that received an interruption, separately for negative and positive interjections.14

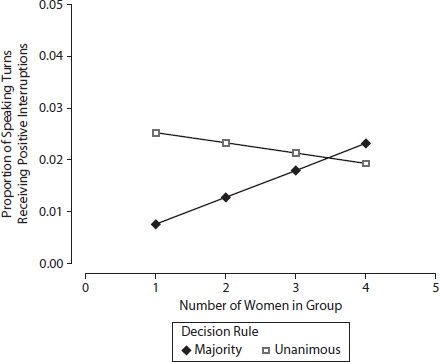

We begin by comparing women to men. We take the proportion of a person’s speaking turns that received a positive interruption and calculate a gender ratio—the group’s average for women divided by its average for men, for mixed gender groups. Figure 8.2 shows the raw percentages, grouping the minority conditions together and the majority conditions together, to increase the statistical power to detect differences between them. One on the y-axis of figure 8.2 indicates gender parity; numbers below one indicate women are receiving fewer positive interruptions on average than men.

Figure 8.2 makes a number of points. First, the conditions shift the likelihood that women will receive a positive interruption. Second, minority women under majority rule are much worse off than other women or men. These women receive positive affirmations at less than half the rate enjoyed by men in their group: 40% of men’s, to be exact. Third, this visual impression is confirmed by statistical significance tests, for the most part.15 The effect of rule on groups with minority women is statistically significant; minority women are far more disadvantaged than men in their group under majority than unanimous rule (p = 0.01, two-tailed, group-level). Also, as expected, the effect of composition on groups with majority rule is significant; under majority rule, majority women do much better than minority women, as compared to men in their group (p = 0.005, two-tailed). Fourth, as expected, composition does not have this effect with unanimous rule—increasing numbers of women does not matter under unanimous rule (p = 0.73). The final test fails: the effect of rule on majority-female groups is not statistically significant, contrary to our expectation, indicating that majority rule is no better than unanimous rule for majority-female groups.

One other finding (seen in chapter appendix figure A8.3) also underscores the unusually bad situation women face when they are a small minority under majority rule. Lone women under that rule issue one of the highest rates of positive reinforcement of any gender group under any condition. Yet they receive the lowest rate of affirmation in turn. These women receive only about one-fourth of the affirmations that lone women get with unanimous rule, and about half of the affirmations that lone men receive under majority rule. The majority-rule example above shows precisely this dynamic.

These tests largely support our basic argument: what the conditions do for gender equality is to correct the high level of inequality that minority women experience under majority rule. This can be achieved either by introducing unanimous rule in groups with few women or by increasing the number of women and keeping majority rule. Majority rule is good for majority women, while unanimous rule is good for minority women, relative to the men in their group.

In sum, women’s inequality relative to men in the group is marked, but only where their status is lowest—as a minority under majority rule. It manifests especially in the gap in affirmations one experiences when one is speaking. Unanimous rule reverses the inequality in the experience of warmth and support regardless of women’s numbers. So do numbers.

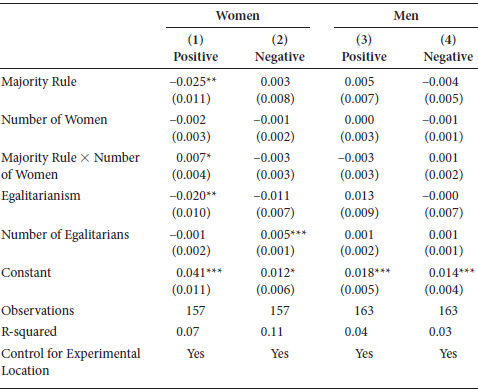

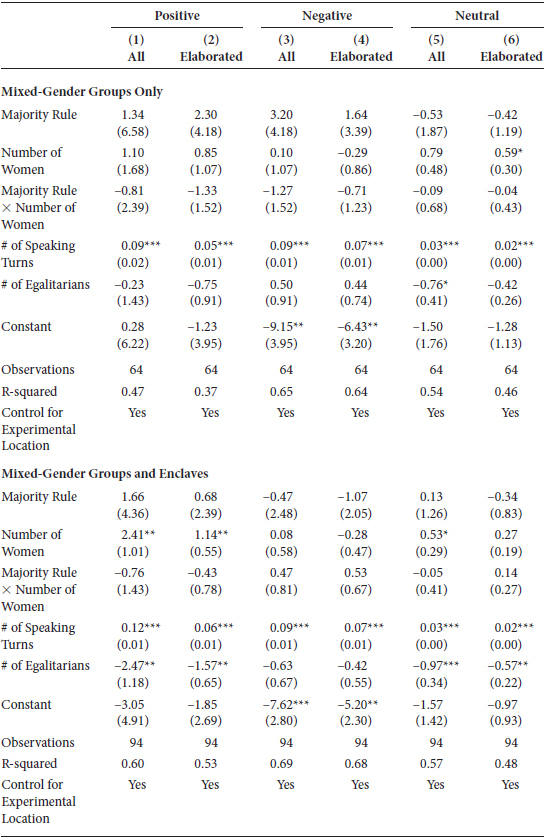

To test these hypotheses more rigorously, table 8.2 presents regressions of the proportion of speaking turns that are positively interrupted, and those that are negatively interrupted, separately for interrupted men and women.16 The only significant coefficients are for women’s positively interrupted proportion of speaking turns (column 1), and they show the expected pattern: women do worst as a minority under majority rule, and improve their situation as their numbers rise under that rule. Figure 8.3 displays these results.

Figure 8.3 shows, as expected, that women’s positively interrupted proportion of speaking turns increases as the number of women rises under majority rule. Again, we see the difference that rule makes to the effect of numbers—composition does not have an effect under unanimous rule. There are no significant effects on the negative interruptions women received (table 8.2, column 2). The rule and rule-composition interaction coefficients for negative interruptions do run in the opposite direction from those in the positive column, but those changes are not significant. Men’s experience of interruptions is unaffected (columns 3, 4).17 In sum, composition helps women receive increased positive reassurance, but only under majority rule, and unanimous rule protects minority women.18 Men are not affected, further indicating that the pattern of interruptions acts on women’s authority but not on men’s.

Table 8.2: Proportion of Turns Receiving Positive and Negative Interruptions, Mixed-Gender Groups Only

Note: Individual-level analysis. Cluster robust standard errors in parentheses. *** p < 0.01, ** p < 0.05, * p < 0.10, two-tailed test.

The raw data on positive and negative interruptions also allows us to shed some light on a question we posed in our earlier chapter on floor time. There we saw that token men under unanimous rule take up an unusually high proportion of the group’s time. We did not know whether this was the result of dominant behavior by the man or by deferential or friendly behavior on the part of the women in the group. Now, in figure A8.3, we can see that this token male is not engaging in power plays to obtain disproportionate floor time. His rate of issuing negative interruptions is no higher than that of other men or women. Neither is there evidence that women in these groups are attempting to wrest control from the token male—the rate of negatively interrupted turns that men receive from women does not move across the conditions (regression not shown).19 Instead, we see that the token man in these unanimous rule groups receives a high rate of positive interruptions (chapter appendix figure A8.3). It seems that token men take unusually high floor times with the encouragement of the women around them, rather than by using dominant forms of speech. In these groups, women forego the power of numbers voluntarily and actively encourage the man among them to take a position of leadership.

Figure 8.3. Proportion of women’s speaking turns receiving a positive interruption, mixed groups only.

Overall, we have now seen that settings that empower women do so by increasing the positive encouragement they receive.20 Relative to other women, and to men in their own group and in other conditions, women receive far fewer encouragements when in the minority under majority rule. In this sense, unanimous rule protects minority women. There, women receive concrete evidence that they are indeed being listened to. Similarly, we now understand why majority rule is bad for minority women—they seldom hear encouragement when they speak. And as we saw in earlier chapters, women’s proclivity to speak in the masculine setting of group political discussion is more fragile than men’s when their status is low. The combination of a few negative feedback and sparse positive feedback, deceptively neutral and inconsequential, represents a powerful dose of invalidation for women—and not for men.

ELABORATED INTERJECTIONS

Next we examine whether the interjections come with elaboration on the current speaker’s comments. Elaboration is an indicator of the quality of discussion—more elaboration enriches the discussion by adding content that is not currently articulated. In addition, more relevant to our study, elaboration added to a negative interruption softens the interruption; conversely, a negative interruption without elaboration tilts more toward pure hostility rather than toward conflictual engagement. However, elaboration of a positive comment works (moderately) the other way—elaboration allows the interjector to add their own thoughts and thus detract attention from the speaker, while unelaborated positive interjections simply support the speaker. So elaboration on the positive means a moderate loss of power by the original speaker, while elaboration on the negative protects the speaker’s authority. Consistent with this interpretation, our initial look in chapter appendix figure A8.1 revealed that negative interruptions are more likely to be elaborated than are positive interruptions. This tells us that negative interruptions that are not elaborated are probably perceived as hostile, and the elaboration is meant to soften them. We assume that elaborating on the negative is an attempt to soften the hostility of the interruption and is an indicator of respect to the interruptee.

Unelaborated positive interruption

0:01:58.8 |

Man C: [The floor income] should be high enough to support a person, but low enough that it’s uncomfortable— |

0:02:12.8 |

Woman D: [interposing] I agree. |

0:02:12.3 |

Man C: —so that they don’t feel content to sit there and not do anything and mooch off of society. |

Elaborated positive interruption

0:06:59 |

Man E: I guess it depends on where you set it. I think the problem you run into, I just think that whenever you cap what someone can do, like, this destroys incentive. You do not want to push things. |

0:07:09 |

Woman D: [interposing] If you know anything about economics, then you know that that is totally every principle of it. |

Unelaborated negative interruption

00:04:38 |

Woman E: I would say like the set range, that way every-body gets approximately the same amount. Say you work a little harder … you get a little bit more, but then nobody is screwed. That’s a good goal. |

00:04:42 |

Man A: It’s not the most ideal. |

Elaborated negative interruption

00:24:23 |

Man D: Yeah, the floor one. It’s just not—I don’t really—I mean, it may not have—I just don’t see too many negatives of it— |

00:24:39 |

Woman C: [interposing] You’re almost doubling the low class. |

00:24:40 |

Man D: —as compared to the no redistribution. |

Accordingly, we divide elaborations into negative and positive and examine them separately. We want to see if a rise in women’s status from rule and numbers increases the elaborated proportion of negative interruptions issued to women and decreases the elaborated proportion of positive interruptions women receive.

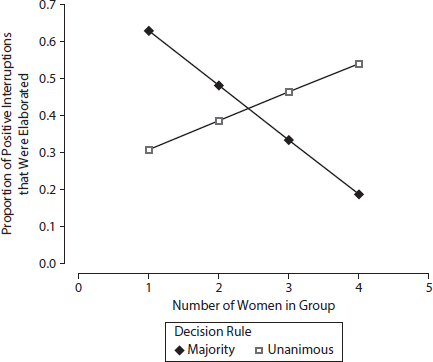

The familiar interaction pattern comes through cleanly in figure 8.4, which shows the elaborated proportion of negative interruptions women received from either men or women. The figure shows predicted values from a regression in chapter appendix table A8.1 (column 1).21 Women receive more respect from those around them as their status rises. As we saw in the earlier analysis of talk time, rising numbers alone are no guarantee of greater respect; women’s numbers only help when numbers carry an advantage, that is, under majority rule.

Figure 8.4. Elaborated proportion of negative interruptions received by women from men and women, mixed groups only. Note: Based on predicted values from chapter appendix table A8.1, column 1.

When we examine these effects separately by each gender combination in the dyad, we find one model with effects even approaching significance—and that is for men positively interrupting women. Table 8.3 shows that the positive interruptions women receive from men are much less likely to be elaborated in conditions where women have higher status—the familiar interaction effect we find throughout our analyses shows up here and is highly significant. We also see the protective effect of unanimous rule for minority women.22 Figure 8.5 shows the predicted values from the model in table 8.3 and clearly illustrates how men change their elaboration behavior as women’s status increases. Under majority rule when women’s status is the lowest, nearly 63% of the positive interruptions they receive from men are elaborated; this decreases to about 19% when women are at their strongest. Similarly, women receive more positive elaborations from men as the unanimous rule’s protective effect weakens.

Table 8.3: Elaborated Proportion of Positive Interruptions to Women from Men, Mixed-Gender Groups Only

Majority Rule |

0.545** |

|

(0.239) |

Number of Women |

0.077 |

|

(0.058) |

Majority Rule × Number of Women |

–0.225*** |

|

(0.079) |

Egalitarianism |

0.022 |

|

(0.284) |

Number of Egalitarians |

–0.003 |

|

(0.047) |

Constant |

0.232 |

|

(0.208) |

Observations |

83 |

R-squared |

0.11 |

Control for Experimental Location |

Yes |

Note: Individual-level analysis. Cluster robust standard errors in parentheses. *** p < 0.01, ** p < 0.05, * p< 0.10, two-tailed test.

Women receive a more polite form of disagreement when their status is high (though this effect only approaches significance), and in such settings they also receive considerably more unambiguous support when interrupted, specifically from men. Using a positively worded statement when interrupting a speaker is a standard form of politeness that saves face and preempts conflict. But it can be a means to achieving an instrumental end. A polite maneuver designed to take the floor for oneself serves the goal of articulating one’s own view. Men are much less likely to use such polite means to assert their thoughts during women’s floor time as women’s status rises. Put differently, men are more likely to simply affirm women rather than to affirm them while taking the floor for their own thoughts. That only women experience this rise in simple support, while men do not, suggests that women’s shifting status is at work. Furthermore, men are the ones shifting their behavior, and they do so only in addressing women. This again supports the notion that the explanation lies in men’s recognition of women’s status. Men are the ones instantiating women’s rise in status in the group.

Overall, we found a number of ways in which women’s numbers and the group’s rules—our indicators of women’s status—shape women’s experience of authority. First, women receive fewer positive interruptions when their status is low, and thus experience a high negative-to-positive balance of interjections, particularly from men. Second, what positive interruptions they do receive are more likely to include elaborations that involve intrusions upon their floor time, again particularly from men. Third, the negative signals directed toward women are more likely to be hostile—raw expressions of disagreement not accompanied by any attempt to soften the comment with further elaboration, from both men and women. It is not just that women are receiving fewer positive interruptions in conditions where they have low status (though that’s important), it is also that the positives are less affirming and the negative signals are more negative.

Figure 8.5. Elaborated proportion of positive interruptions received by women from men, mixed groups only.

THE EFFECTS OF INTERRUPTIONS

Next we ask whether the balance of positivity and negativity is associated with other indicators of authority, measured after discussion. Do interruptions have an effect on perceived influence in the eyes of others? Recall from chapter 5 that the conditions of deliberation affect the influence of deliberators as measured by the number of other members who chose a given member as “the most influential member of your group during the group discussion” (ranging from 0 to 4). We found there that the more women, the more likely is the average woman to be chosen as most influential—but only under majority rule. The effect of composition reverses under unanimous rule, where the average woman is more likely to be seen as influential when women are few than when they are many. Now we can see if interruptions help explain these patterns of influence.23

Figure 8.6 displays the effects from panel A of table 8.4. That table shows the negative binomial regression estimates of the effect of the person’s negative balance of interruptions received on others’ ratings of that person’s influence in the group, controlling on talkativeness, for both mixed-gender and enclave groups. The figure and table show that for women especially, the higher their balance of negative interruptions, the fewer the influence votes they receive. The figure shows that as the proportion of negative interruptions moves across its range, the perceived influence of women in mixed-gender groups drops by over two-thirds. The effect is similar in all-female groups, but much smaller for men, whether in mixed or all-male groups.

It seems that women’s authority is especially affected by the experience of affirmation rather than hostility in conversation. The conditions of deliberation that cause male members to negatively interrupt women without providing significant positive feedback also cause women to lose standing as deliberators. What groups do while interacting can lower or raise women’s ability to make valued contributions to the collective.

And what about participants’ sense of their own influence? The results in panel B of table 8.4 show that on the key measure of “my opinions were influential,” the negative balance of interruptions again matters. A higher balance of negative interruptions is associated with lower perceptions of women’s self-efficacy in discussion (column 1), but not with men’s (columns 3 and 4). Furthermore, the effect on women applies only when they interact with men; when we examine all-female enclaves separately, the effect decreases and loses statistical significance (column 2). Women’s sense of their contribution to the group depends on the balance of interjections they receive, but not when they are in all-female groups. One of the functions of women’s enclaves is to take the sting out of other people’s responses to one’s opinions. Men do not need male enclaves to be able to brush off hostility or the absence of approval.

Table 8.4: Panel A: Effect of Negative Proportion of Interruptions Received on Others’ Ratings of Speaker’s Influence, All Groups

Note: Coefficients from a negative binomial model. Individual-level analysis. Cluster robust standard errors in parentheses. *** p < 0.01, ** p < 0.05, * p < 0.10, two-tailed test.

Panel B: Effect of Negative Proportion of Interruptions Received on Self-Rating of Speaker’s Influence, All Groups

Note: Individual-level analysis. Cluster robust standard errors in parentheses. *** p < 0.01, ** p < 0.05, * p < 0.10, two-tailed test.

Figure 8.6. Effect of negative interruptions on perceptions of women’s influence, mixed groups. Note: Predicted values from table 8.4, panel A, column 1.

Finally, the effect on women’s rating of their own influence holds when we replace the negative balance with the positively interrupted proportion of speaking turns (b = 2.6, SE = 0.85) but not with the negative proportion of turns (the effect is 0.71, SE = 1.26, the wrong sign and not significant).24 A few negative comments do not deter women as long as they also receive a good number of positive reinforcements. Women need positive validation while they speak in order to feel that they matter; men do not. The importance of the positive in communication is underscored by the fact that if the message is positive frequently enough, the negative becomes irrelevant.

A formal test of mediation (Imai, Keele, and Tingley 2010) confirms the basic result. The mixed-group conditions affect women’s influence—in their own eyes and in the eyes of others—in part through their effect on the negative proportion of interruptions received (see online appendix table C8.ii.2). The conditions substantially affect the balance of negativity directed toward women, and it, in turn, affects women’s authority. In sum, the relative negativity one receives is a crucial factor in women’s—and others’—sense of their influence. The conditions of discussion shape the kinds of social interactions women experience, and those interactions can elevate or depress women’s authority.

Positive interruptions play a particularly helpful role for women who entered the discussion with low levels of confidence in their ability to participate. In chapter 6 we presented evidence that confidence enables women’s increased participation, especially in conditions where they are disempowered. Now we can ask how the dynamics of discussion affect women with varying levels of confidence. Pooling across all mixed-gender conditions, we find that for both low- and high-confidence women, a higher proportion of positive interruptions is correlated with increased talk time during the discussion and more influence votes from other members of the group afterward (online appendix table C8.ii.3). But positive interruptions also yield a unique benefit to low-confidence women, increasing their self-rated sense of efficacy at a higher rate than that of high-confidence women (the difference-in-differences is significant at p < 0.09, two-tailed test; online appendix table C8.ii.4).25 Put differently, confidence moderates the effect of positive interruptions on feeling that one’s opinions influenced the group’s discussion and eventual decision.26 When they receive few positive interruptions, women with low predeliberation confidence report lower levels of postdiscussion efficacy than those who entered the discussion with more confidence. But when they receive more encouraging feedback in the form of a higher rate of positive interruptions, low-confidence women equal and even surpass high-confidence women in feeling that their opinions helped to shape the group (online appendix figure C8.ii.1).27 This effect holds only for mixed-gender groups. In all-female enclaves, efficacy is unaffected by positive interruptions.

Positive interruptions are thus especially important for women who entered the discussion harboring some concerns about their ability to participate effectively, and only when they interact with men. Strong positive signals during the discussion provide a substantial boost to the postdiscussion efficacy of those women, which they appear to need more than others do. By comparison, positive interruptions have no effect on the efficacy of men, regardless of their level of prediscussion confidence.28

Another way to examine the encouraging effects of interruptions is to ask if positive interruptions elevate the speaker’s percentage of talk in the group. In table 8.5 we find that for female speakers, the answer is yes, but only when the encouragement is issued by the gender empowered in that condition. That is, women accelerate their talk the more they are encouraged either by men in conditions where women are least empowered (majority rule, few women), or by women when women are empowered (majority rule, majority women). That is, women speak more when they get more positive interruptions from men, but not from women, when women are disempowered, and they speak more when they get positive encouragement from women but not from men when women are the dominant gender. Female speakers thus calibrate the volume of their speech to the more powerful gender in the group. Men are not affected in this way.29

We have seen that the experience of interruptions carries crucial consequences for deliberators. In particular, the relative negativity one receives when other members engage with one’s speech is a crucial factor in women’s sense of their influence and in others’ perception of women’s influence. The heart of the matter is whether women receive positive signals; when they do, they can withstand the occasional negative response.

And again we see that the same experience can elicit very different responses by men and women. Women need frequent positive validation while they speak in order to feel that they matter; men do not.30

Table 8.5: Effect of the Proportion of Speaking Turns Receiving Positive Interruptions on Women’s Proportion Talk

Note: Dependent variable in all models is Proportion Talk. Individual-level analysis. Cluster robust standard errors in parentheses. *** p < 0.01, ** p < 0.05, * p < 0.10, two-tailed test.

Finally, we argued that the level of rapport in the group not only matters to women, but also that a preponderance of women may elevate it, and particularly so in female enclaves. So now we pose our final question: when does the group take on an affirming, friendly, and inviting character? For this analysis we examine the group as a whole without differentiating women and men. We control on location, the number of egalitarians, and the group’s average number of speaking turns.

Table 8.6 shows that the number of women matters to the tenor of interaction in the group—but only with enclave groups included. As the number of women increases, the number of positive interjections in the group rises (without regard to rule).31 In addition, when we look only at positive interruptions that elaborated on the content of the initial speaker’s thought, we find the same result—the more women, the more positive elaborated interruptions in the group. That is, the positive tone is accompanied by meaningful content. The interrupter offers some substance that goes beyond what the speaker articulated. Not only are predominantly female groups warmer and friendlier, they also use this rapport and friendliness to advance the discussion and provide a meaningful exchange of views.32

This interpretation rests on the assumption that women elevate the positive—and not the negative. To test this hypothesis, we look at negative interruptions. These results are displayed next to the positive interruptions results in table 8.6. Unlike positive interjections, negative interruptions remain flat across the conditions. Neither do the conditions affect the number of negative interruptions with elaboration.33

Finally, table 8.6 shows that when we omit the enclave groups and examine only mixed-gender groups, the only significant effect is for gender composition on neutral interruptions with elaboration. Positive interruptions do not rise with the number of women when women interact with men. They increase only among female enclave groups. That is, the warmth effect from greater numbers of women is located specifically in gender-homogeneous groups.34

These results tell us that the chief effect on groups as a whole is located with women’s enclaves. These settings are exceptionally supportive. Further, these results imply that this affirmation is the main way that elaboration is conveyed when one speaker directly engages another. In female enclaves, elaboration is achieved primarily through positive rather than negative or neutral interruptions. The warm tone of the group’s exchange directly affects the group’s success in providing new thoughts that add meaningful content to what is being said. Women’s enclaves create an inclusive discussion tone, and this affirming tone, unlike a hostile or conflictual tone, carries with it the contribution of one speaker to another’s thoughts.

Table 8.6: Group-Level Effects on Total Number of Interruptions, Mixed-Gender and Enclave Groups

Note: Group-level analysis. Standard errors in parentheses. *** p < 0.01, ** p < 0.05, * p < 0.10, two-tailed test.

We began this chapter with a question. Do women’s numbers affect the nature of the interaction and thus women’s ability to express their voice? Our results suggest that the answer is yes, but the rule moderates the effect. In mixed-gender conditions, groups with more women and majority rule, and groups with few women and unanimous rule, produce a more positive interaction style among the members. Moreover, women are the main beneficiaries of this style. It goes hand in hand with greater perceived influence, self-efficacy, and their active participation in discussion.

Some highlights of our detailed findings reveal the basic dynamics at work. More women make the balance of interruptions more positive under majority (but not unanimous) rule. This mainly occurs through more positive interruptions. Positive interruptions from men are less likely to be elaborated as women’s status rises, providing women with a more pure form of support and attention. Negative interruptions from men and women are (marginally) more likely to be elaborated, softening the disagreement women encounter while speaking.

Especially badly off are women in the gender minority under majority rule. For these women, deliberation is a negative experience in which their speech is interrupted in a dismissive manner and their words rarely affirmed. Lone women, for example, issue a higher rate of positive interjections than any other gender subgroup but receive the least in return (in each case, relative to their speaking turns). At 20% or 40% of the group, women are less than half as likely as men in their group to experience approval while speaking.

In an earlier chapter we saw that in this majority-rule minority-female situation, low-confidence women are particularly quiet. It may be that the pattern of interruptions we documented partly explains why these women react so strongly to those conditions. The absence of positive affirmation in these conditions would likely affect women with low confidence especially badly. Evidence presented here is consistent with this notion.35 Although we found an association for all women between receiving positive interruptions and elevated levels of talk and of influence votes, the association between positive interruptions and efficacy is especially strong for low-confidence women.

The results fit a broader pattern of gender inequality in deliberation. In the usual circumstances of political discussion, women are a numerical minority, and the group uses a norm of majority rule, whether it is officially stated or implied; thus, the expected style of interaction is one of individual agency and conflict. There, behavior tends to conform to a gendered pattern of differential power. Men tend to assert themselves through actions that society associates with higher power or status; women tend to behave in the opposite.36

Our large-N findings replicate those from legislatures, such as the confirmation hearings for Justice David Souter or the Colorado state legislature. There, women encounter more hostile speech patterns than men (Kathlene 1994). These cases also illustrate our findings that the ability of women to be heard in deliberation depends on the forms of speech. The pattern of interruptions one receives is a significant indicator of and instantiation of one’s authority. Most importantly, Mattei’s narrative fits well with our results from minority-female, majority-rule conditions: women constituted 40% of the witnesses, yet “the average male witness had a higher proportion of floor time,” and (the all-male) senators “interrupted women more frequently than men.” That this is a gender effect is driven home by her finding that “senators from both parties were more likely to undermine the authority of female witnesses than that of males, particularly through higher rates of empirical questions, disagreements, challenges, and the citation of other authorities to contradict women’s testimony, and the characterization of women’s words as unreasonable” (1998, 459 for all quotes; emphasis ours).

That is, we see in the lab what we see in the most consequential settings of power: when the procedure does not account for the default inequalities between men and women, even near-equal levels descriptive representation do not lead to equal substantive representation. Substantive representation, whether in the most official or the most casual public settings, depends on the social structure—namely, gender composition—and on institutional norms and procedures that are neutral on their face but carry profound consequences for social inequality. Finally, these real-world cases illustrate our own findings in the sense that the ability of women to be heard depends on the forms of speech. The pattern of interruptions one receives is a significant indicator of and instantiation of one’s authority and goes hand in hand with other such indicators, such as floor time. Not only the logical and evidentiary content of speech matters, its social content and meaning also matter a great deal, and perhaps matter most of all.

Similar patterns obtain in two other, very different settings. High-performing work teams exhibit a ratio of six positive to one negative comments, while poor performers have a ratio of about 1 positive comment for every 3 negative (Losada and Heaphy 2004). In our study, the most negatively interrupted members—minority women under majority rule—experience a ratio similar to that of the poorly functioning work teams. The implication is that the typical setting for political discussion, where women are a numerical minority under majority rule, is a dysfunctional one for women.

This turns out to be a common pattern in an altogether different realm—marriage. Studies of married couples by the psychologist John Gottman find that what predicts marital longevity and satisfaction is not the negativity but the positivity of the couple’s interaction (Gottman 1994). A couple may exchange a large number of negative comments, but these are irrelevant as long as the couple also exchanges a far larger number of positive comments (five to one, to be exact). The results in this chapter point in a similar direction. The positive percentage of interruptions is a crucial indicator of successful interaction in a variety of settings.

Our key point, however, is not found in previous studies; when the procedure does not account for the default inequalities between men and women, increasing descriptive representation does not increase other forms of representation. Representation depends not only on gender composition but also on institutional norms and procedures that are neutral on their face but carry profound consequences for social inequality. While our results paint a dark portrait of gender inequality, the effects of unanimous rule are heartening for advocates of deliberation and for the goal of social justice. The dismal situation of minority women under majority rule improves dramatically under unanimous rule. The decision rule is a simple yet powerful element of institutional design. It restrains the disrespect that men sometimes direct toward women where women have low status, and raises their affirmations of women’s speech. In these ways, it creates a norm of interaction that actively includes women. Simple institutional procedures can create equality and justice in the process and outcome of representation.

When we alter the conditions of discussion, the ones to change their behavior are, mostly, men. Men become nicer to women as the conditions elevate women’s status. Some might say something like this: “well, why don’t women just talk more? It’s women’s responsibility to speak—no rule prevents them from doing so, and no one stands in their way.” Our reply is our finding that men change their behavior in such a way as to make women’s participation less rewarding and more difficult. The process is subtle and, by any formal measure, legitimate, but it ends up carrying particularly negative consequences for women.

The assumption that women are not valuable in discussions that decide the fate of the collective produces gender inequality. If women are not needed for making decisions, then they will not be much included. Conversely, our findings about rule imply that when women are needed, women are included. Women are needed when they are a majority under rules that give a majority power and when they are a minority under rules that give the minority power. The rule can elegantly set in motion a whole set of conversational practices that increase the warmth and affirmation that in turn elevate women’s representation. Simple institutional procedures can equalize representation.

In addition, we now know the secret to women’s enclaves: they are nice! Women’s distinctive ways of interacting—supporting one another with considerable positive feedback—come to the fore in these all-female groups. This dynamic takes the sting off negative interruptions, making women more resilient in the face of engaged opposition. To be sure, the average woman’s experience is not qualitatively different in enclaves than in the best of the majority-female conditions; however, when we look at the group as a whole, all-female groups emerge as the most mutually supportive environments, and only there is women’s sense of efficacy in the group impervious to the effects of negative interjections.

We also argued that interruptions are a means to establish a norm of rapport. Centuries ago the French observer Tocqueville was impressed by what he viewed as Americans’ zeal to form civic associations. One of the remarkable characteristics of these associations, he maintained, is the face-to-face meeting: “the power of meeting,” he noted, lies in part in its “warmth and energy” ([1835] 2006, book 1, chapter 12). We saw that female enclaves are the most mutually affirming groups. In this sense, political philosophers are right to endorse the notion that disadvantaged groups can benefit from spaces of their own. Now we can say why this insight may be on the mark. These groups are distinguished from others specifically on the dimension of mutual support and rapport. Interestingly, these groups are no different from other groups in their negative interruptions. What they do instead is supply more positive interjections. This changes the balance of negative to positive.

The results fit a broader pattern of gender inequality during interactions between men and women. In the usual circumstances of political discussion in the United States, women are reluctant to participate in the exchange as fully as men do. In these settings, not only are women a minority, but there is also a norm of majority rule, whether it is officially stated or implied by the political context. There, where women tend to be less numerous than men and where the expected style of interaction is one of individual agency and conflict, behavior tends to conform to a gendered pattern of differential power. Men tend to assert themselves through actions that society associates with higher power or status; women tend in turn to behave in ways that signal lower status or power. 37

Our results also speak to the ideal of civility in deliberation (Kingwell 1995). For some liberal theorists, such as Gutmann and Thompson (1996), reciprocity is the foundation of deliberative democracy, and civility is an integral part of reciprocity (Macedo 1999). On this view, civility is a fundamental civic virtue in a liberal democracy (see Herbst 2010, 13; White 2006). For other theorists, civility is also necessary, though in the specific form of a display of respect in the face of morally abhorrent actions (Calhoun 2005).

We view civility as inadequate for deliberation on two grounds. First, theories of dialogue or deliberation that advocate civility as a virtue tend to ignore the social stratification function of civility. Sociological and historical accounts emphasize that civility entails “markers of politeness, decorum, courtesy or good manners that enabled one to distinguish oneself from others” who are more “savage” (White 2006, 447). Civil behavior was appropriate to members of the upper classes in European and European-dominated societies; other social classes were deemed incapable of civility because they were incapable of self-regulation and thus of regulating others (Sapiro 1999). That is, civility creates a social distinction between privileged, high-status groups, whose civil manner marks them as socially superior and capable of governance, and their inferiors. The flip side of the same coin is that charges of incivility could be used to enforce political conformity and silence the numerical minority, in the view of John Stuart Mill (Herbst 2010, 16). “‘Invective, sarcasm,’ and other forms of rudeness were only denounced when they were used ‘against the prevailing opinion’” (Mill quoted in Herbst 2010, 16). A more contemporary twist on the uses of the accusation of incivility is that when groups such as women attempt to challenge the political or social hierarchy, they may be accused of uncivil behavior (Sapiro 1999; Hertz and Reverby 1995).38 A final variation on this theme is that dominant groups’ dominant behavior toward subordinate groups may too often be unconstrained by norms of civility; as Calhoun puts it, “social norms of civility may fail to condemn the contemptuous treatment of socially disesteemed groups, because they interpret such contempt as civilly displaying the appropriate measure of respect” (2005, 266).39 Thus the concept of civility has intellectual and historical roots in a hierarchical and time-bound meaning that we reject.

Second, civility is a social code of politeness (Brown and Levinson 1987), and politeness can be quite cold and indifferent in its emotional tone. Civility merely dictates that the listener get out of the speaker’s way by avoiding negative interruptions and hostility. Witness the emphasis in the historical concept of civility on self-restraint, quiet (Kingwell 1995), and other forms of self-control (Herbst 2010, 13–16; White 2006). Avoiding action that gives offense is an important criterion, but it is not sufficient.40 A narrow focus on civility can lead to a cold and formal proceduralism or politeness that is insufficient for the inclusion of women. Real inclusion requires something more than the absence of rudeness or a recursion to overly formal ways of managing potential disagreements.

We view the key concept for gender equality as rapport rather than civility. To be sure, many women may require that listeners avoid expressions of hostility, contempt, and arrogance. However, at least in this time and place, and given the gendered experiences that shape women before they enter deliberation, women also tend to require something more positive and proactive—affirmation and support, not merely the absence of negative attacks. In fact, our enclave result shows that disagreement per se is not deflating to women at all—as long as it occurs in an environment that is socially supportive. Thus what deliberating groups should strive to achieve is something close to friend-ship (Mansbridge 1983). As sociolinguists put it, friendship is characterized by speech patterns that demonstrate a high level of supportive engagement, a “talking along” that creates solidarity and affirmation (Tannen 2009), camaraderie, and rapport (Lakoff 1975). This is the concept we attempted to measure here, and it differs from the more minimal requirement of politeness, and from the hierarchically inflected concept of civility.

The results also speak to Mansbridge’s work on deliberative democracy, specifically her distinction between adversarial and consensual styles (1983). Mansbridge distinguishes between adversarial modes of decision making, involving voting, majority rule, and the aggregation of individual preferences; and unitary modes, typically associated with small, intimate groups, where the focus is on consensus building.41 In an adversary system, the assumption is that conflict exists and the issue is how to deal with it while preserving individual autonomy and rights, and how to aggregate the preferences that exist in an appropriate way. In a unitary system, the assumption is that members share basic interests, that conflict is resolvable, and that the main task of the group is to function as a unified whole. In unitary groups, the work of politics involves extended discussion of common interests. In adversary groups, the work of politics involves negotiation of competing interests. The distinctions follow from one key question—does the group have deep conflict? Groups with conflict do, and should, use adversarial means. Groups with less conflict and a high level of shared interests and understandings do, and should, use more unitary means. Or so goes the argument.

Our notion of what happens in discussion is close to Mansbridge’s, but we place the emphasis a bit differently. Where Mansbridge sees the prediscussion level of conflicting interests and understandings as the key to whether a group is unitary or adversary, we see a key to the group’s unitary or adversary nature as lying in the dynamics of interaction during discussion. Where Mansbridge tends to see adversary democracy as a characteristic of larger systems, and unitary democracy as a driving force of small groups, we see that the small group can have either adversary or unitary characteristics. Small does not mean unitary; small can be highly adversary. And where Mansbridge classifies the meeting as unitary or adversary based on the use or avoidance of procedures such as majority rule, we classify it as unitary or adversary based on the social aspects of exchange.42

According to our modified concept of adversary versus unitary democracy, some groups are characterized by a highly unitary mode of discussion even though they use the structures of adversary democracy. These are the majority-female groups under majority rule. And by the same token, the same lengthy, face-to-face discussion assuming common interests can be a place where gender inequality is reinforced, as with many women and unanimous rule, or instead a place where women are empowered and men are content with their empowerment—namely, unanimous rule with minority women.