Chapter 1

The Six Sigma System

A New Way to an Old Vision

SIX SIGMA. A new name for an old vision: near-perfect products and services for customers.

Why is Six Sigma so attractive to so many businesses right now? Because being successful and staying successful in business is more challenging today than ever before. In today’s economy, most people provide services rather than making goods and products. And most of those services operate at levels of inefficiency that would close down a factory in a month if it produced as many defects. Six Sigma provides power tools to improve those services to levels of accuracy and quality seen so far only in precision manufacturing.

Companies like General Electric and Sun Microsystems are flexing the Six Sigma system to create new products, improve existing processes, and manage old ones. Leaders of these and other Six Sigma companies know that Six Sigma encompasses a wide variety of simple and advanced tools to solve problems, reduce variation, and delight customers over the long haul. Six Sigma …

♦ Generates quick, demonstrable results linked to a no-nonsense, ambitious goal: To reduce defects (and the costs they entail) to near zero by a target date.

♦ Has built-in mechanisms for holding the gains.

♦ Sets performance goals for everyone.

♦ Enhances value to the customer by exposing “defects” caused by functional bureaucracy and by encouraging managers and employees alike to focus their improvement efforts on the needs of external customers.

♦ Speeds up the rate of improvement by promoting learning across functions.

♦ Improves our ability to execute strategic changes.

You can find descriptions of successful applications of Six Sigma in The Six Sigma Way. This chapter reviews key concepts introduced in that book—as a refresher for those who have read it and background for those who have not.

What Is Six Sigma?

If Six Sigma is so great, where has it been hiding all these years? Like most great inventions, Six Sigma is not all “new.” It combines some of the best techniques of the past with recent breakthroughs in management thinking and plain old common sense. For example, Balanced Scorecards are a relatively recent addition to management practices, while many of the statistical measurement tools used in Six Sigma have been around since the 1940s and earlier.

The term “Six Sigma” is a reference to a particular goal of reducing defects to near zero. Sigma is the Greek letter statisticians use to represent the “standard deviation of a population.” The sigma, or standard deviation, tells you how much variability there is within a group of items (the “population”). The more variation there is, the bigger the standard deviation. You might buy three shirts with the “same” sleeve length only to discover that none them are exactly the length printed on the label: two are shorter than the stated length, and the other is nearly an inch longer—quite a bit of “standard deviation.”

In statistical terms, therefore, the purpose of Six Sigma is to reduce variation to achieve very small standard deviations so that almost all of your products or services meet or exceed customer expectations.

Variation and Customer Requirements

Traditionally, businesses have described their products and services in terms of averages: average cost, average time to deliver a product, and so on. Even hospitals have a measure for the average number of patients who pick up a new infection during their stay.

Trouble is, averages can hide lots of problems. With the way that most processes operate today, if you promise customers to deliver packages within two working days of getting their order, and your average delivery time is two days, many of the packages will be delivered in more than two days—having an average of two days means some packages take longer and some take less. If you want all packages to be delivered in two days or less, you’ll have to dramatically eliminate problems and variations in your process.

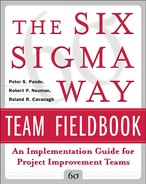

Here’s an example from The Six Sigma Way: you want your “drive to work” process to produce defects (early or late arrivals) no more often than 3.4 trips out of every million trips you make. Your target arrival time at work is 8:30 a.m., but you’re willing to live with a few minutes either way, say 8:28 to 8:32 a.m. Since your drive normally takes you 18 minutes, this means your target commute time is anywhere between 16 and 20 minutes. You gather data on your actual commute times, and create a chart like that shown in Figure 1-1.

There will always be some variation in a process: the core issue is whether that variation means your services and products fall within or beyond customer requirements. If you want to be a Six Sigma commuter, the problem is that your process produces a lot of defects (late or early arrival times).

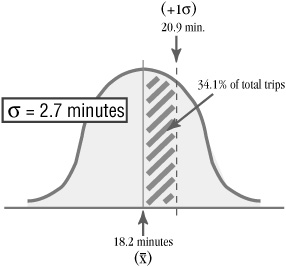

So you set about improving your process. You find the route that is most reliable (has the least traffic and fewest stop lights), you get up when your alarm clock first goes off, you recalibrate your cruise control, etc. After all your changes have been implemented, you gather more data. And voilà, you have become a Six Sigma commuter. The new standard deviation of just 1/3 of a minute means the variation in your process practically guarantees that you will always arrive within 16 to 21 minutes of leaving your house (see Figure 1-2).

Figure 1-1. Drive times to work

Figure 1-2. Improved drive times

This example has direct meaning for the business world. If we promise on-time airline departures, but actual departures vary from 5 to 30 minutes late, customers will understandably be angry and take their business elsewhere (except it might be hard to find an airline that does that good!). And an electric toaster that toasts the bread today but burns it tomorrow—at the same darkness setting—will find its way back to the store, along with an unhappy purchaser.

What happens when we achieve Six Sigma performance? For a Six Sigma commuter, it means predicting commute time very precisely every day. And a “defect”—a commute taking less than 16 or more than 21 minutes—would happen only 3.4 out of every 1 million commutes (may we live that long!).

Defects and Sigma Levels

One virtue of Six Sigma is that it translates the messiness of variation into a clear black-or-white measure of success: either a product or service meets customer requirements or it doesn’t. Anything that does not meet customer requirements is called a defect. A hotdog at the fair with mustard is a defect if the customer asked for ketchup. A rude reception clerk is providing defective service. A bad paint job on a new car is a defect; a late delivery is a defect; and so on.

If you can define and measure customer requirements, you can calculate both the number of defects in your process and outputs as well as the process yield, the percentage of good products and services produced (meaning they are without defects). There are simple tables that let you convert yield into sigma levels.

Another approach to determining a sigma level is to calculate how many defects occur compared to the number of opportunities there are in the product or service for things to go wrong. The outcome of this calculation is called Defects per Million Opportunities (DPMO), which is another way to calculate the Sigma Level or yield of a process.

System Alignment: Tracking the Xs and Ys

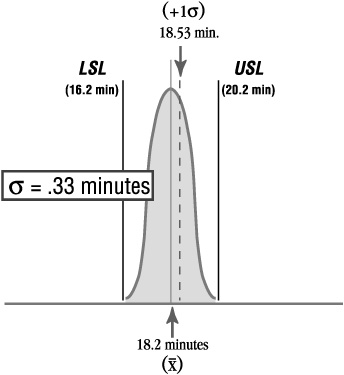

Six Sigma companies commonly use shorthand to describe some key ideas when thinking about their own closed-loop business system. For example, “X” is shorthand for a cause of a problem or one of the many variables affecting a business process; “Y” is an outcome of the processes. For a bakery, the quality of the flour used and the temperature of the ovens are some of the key Xs to be measured, with the loaf itself being the key Y, along with the satisfaction of a hungry customer. Identifying and measuring such critical Xs and Ys are basic tasks in Six Sigma organizations.

Measuring Xs and Ys isn’t an end in itself. Xs or causes have to be connected to critical Ys or effects. For example,

Details on calculating sigma levels are provided in Chapter 9. You’ll also find a worksheet and conversion table in Chapter 10.

Many companies and managers have a poor understanding of the relationship between their own critical Xs and Ys as they pedal along. They keep their corporate bike upright through a mixture of luck and past experience, or by making jerky corrections when the road suddenly changes. Six Sigma managers, on the other hand, use measures of process, customers, and suppliers to be more like experienced cyclists who anticipate problems or respond instantly and smoothly to changes around them.

As you start working on a Six Sigma team, try to become more aware of the outputs you want to achieve (your Ys) and what factors will affect how you get there (the Xs). Becoming more attuned to factors and their effects will help you focus your efforts more strategically. Also remember to link your Ys to what your customers really want—not just to what you think they need or what’s convenient to you.

Six Ingredients of Six Sigma

The Six Sigma Way introduced six critical ingredients needed to achieve Six Sigma capability within an organization:

1. Genuine focus on the customer.

2. Data- and fact-driven management.

3. Process focus, management, and improvement.

4. Proactive management.

5. Boundaryless collaboration.

6. Drive for perfection, tolerate failure.

These ingredients are woven throughout this book and recapped below.

1. Genuine Focus on the Customer

Although companies have long proclaimed that “The Customer is Number One” or “Always Right,” few businesses have actually succeeded in improving their understanding of their customers’ processes and requirements. Many companies claim to meet customer requirements when they actually spend lots of time trying to convince the customer that what they bought is really what they wanted. (Remember the last time you had a phone or cable TV installed and were told that you’d have to spend a whole morning or afternoon waiting for service— when you’d rather have it done at a specific time? This happens when a service company has not been able to control its processes to the point where it can meet customer requirements!) Even when they have gathered information from customers via surveys and focus groups, the results were often buried in unread reports or acted on long after customers’ needs have changed.

Customer focus is the top priority in Six Sigma. Performance measurement begins and ends with the Voice of the Customer (VOC). “Defects” are failures to meet measurable customer requirements. Six Sigma improvements are defined by their impact on customer satisfaction and the value they add to the customer. One of the first tasks of Six Sigma improvement teams is the definition of customer requirements and the processes that are supposed to meet them.

2. Data- and Fact-Driven Management

Although computers and the internet have flooded the business world with data, you won’t be shocked to learn that many important business decisions are still based on gut-level hunches and unfounded assumptions. Six Sigma teams clarify which measures are key to gauging actual business performance; then they collect and analyze data to understand key variables and process drivers.

Finally, Six Sigma provides answers to the essential questions facing managers and improvement teams every day:

♦ How are we really doing?

♦ How does that compare to where we want to be?

♦ What data do I need to collect to answer the other questions?

3. Process Focus, Management, and Improvement

Whether you’re designing a new product or service, measuring today’s performance, or improving efficiency or customer satisfaction, Six Sigma focuses on the process as the key means to meeting customer requirements.

One of the most impressive impacts of Six Sigma has been to convince leading managers—particularly in service-based functions and businesses—that mastering and improving processes is not a necessary evil, but an essential step toward building competitive advantage by delivering real value to customers. In one of its first meetings the Six Sigma team must identify the core business processes on which customer satisfaction stands or falls.

4. Proactive Management

To be proactive means to act ahead of events; the opposite of being reactive, which means to be behind the curve. In the world of business, being proactive means making a habit of setting and then tracking ambitious goals; establishing clear priorities; rewarding those who prevent fires at least as much as those who put them out; and challenging the way things are done instead of blindly defending the old ways.

Far from being boring, proactive management is actually a good starting point for true creativity, better than bouncing from one panicky crisis to the next. Constant firefighting is the sign of an organization losing control. It’s also a symptom that lots of money’s being wasted on rework and expensive quick fixes.

Six Sigma provides the tools and practices to replace reactive with proactive management. Considering the slim margin for error in today’s business world, being proactive is the only way to fly.

5. Boundaryless Collaboration

Coined at General Electric, “boundarylessness” refers to the job of smashing the barriers that block the flow of ideas and action up and down and across the organization. Billions of dollars are wasted everyday through bickering bureaucracies inside a company that fight one another instead of working for one common cause: providing value to key customers.

Six Sigma requires increased collaboration as people learn about their roles in the big process picture and their relationship to external customers. By putting the customer at the center of the business focus, Six Sigma demands an attitude of using processes to benefit everyone, not simply one or two departments. The Six Sigma improvement team foreshadows the boundaryless organization on a small scale, and can teach much about its benefits to the whole company.

6. Drive for Perfection, Tolerate Failure

Six Sigma places great emphasis on driving for perfection and making sustainable results happen within a useful business time frame. As a consequence, Six Sigma teams often find themselves trying to balance different risks: “Is spending two weeks on data collection worth the effort?” or “Can we afford to change the process knowing that we’ll likely create more problems in the short term as we work out the bugs?”

The biggest risk teams can take is to be afraid to try new methods: Spending time on data collection may seem risky at first glance, but usually it results in better, more effective decisions. Not changing a process means work will go on as it always has, and your results won’t get better.

Fortunately, Six Sigma builds in a good dose of risk management, but the truth is that any company shooting for Six Sigma must be ready for (and willing to learn from) occasional setbacks. As a manager in a Six Sigma company once said, “The good kids have got us as far as they can by coming up with the right answers. Now the bad kids have to move us ahead by challenging everything we do.”

Moving Forward

We’d be surprised if you didn’t say “But we’re already doing some of those things!” That’s not surprising—remember, much of Six Sigma is not new. What is new is the way that Six Sigma pulls all these things into a coherent program backed by determined management leadership.

As you begin the job of leading a Six Sigma team, be honest about the strengths and weaknesses of your company, and be open to trying new things. You’ll get better and faster results if your organization is willing to admit its shortcomings and learn from them.

Review your existing methods to make sure they are helping you improve the delivery of product and service to your customers. If not, you’ll have to change past practices. Deciding exactly what changes will mean the most to your organization and its customers is the subject of most of this book!

Eyes on the Prize: Using Six Sigma Teams as a Learning Tool

Six Sigma teams are formed to address specific business issues and improve processes, products, and services. But if that’s all they do in your organization, you’re missing the bigger picture. It’s short-sighted to make “projects” the sole objective of a Six Sigma effort. No matter whether a project is a huge success or fails to reach its goals, you’ve missed a big opportunity if the participants don’t take new skills and habits back to their jobs after the project is complete. As many of our clients have realized, Six Sigma ideas need to become a way of life.

Never forget Six Sigma teams are a learning tool. Champions and Senior Managers should be studying the teams, the DMAIC improvement process, and the data-driven approach—and then applying those tools to their own daily management processes. If they do not, four or five years from now the organization will still be selecting projects, Black Belts, team members, etc.—only the names will be changed to protect those who refused to do things a better, different way. The organization as a whole will not be evolving, nor will it be anywhere near to reaching Six Sigma quality levels in its key processes.

Every leader in the organization should take on the responsibility of exploiting Six Sigma projects to the fullest extent, asking questions such as “What can we learn from these teams? How are they making gains? What can we apply to our everyday work?” Answering those questions will help your organization become dynamic and profitable, with unparalleled efficiency and customer loyalty. That’s what it means to achieve Six Sigma levels of quality.