Preface

Throughout history, people have believed in mumbo jumbo: in ghosts, voodoo dolls, and witches who could make rivers run backward and pull the moon down from the sky. People have believed that pouring vinegar on door hinges cured headaches, that pentagrams neutralized demons, and that applying a toad to a woman’s breast speeded up alchemical reactions. Even today, people believe in spoon-bending, channeling, astrology, the healing power of pyramids, clairvoyance, communication with the dead, and abduction by extraterrestrials. Polls in the 1980s showed that 23% of Americans believed in reincarnation. Polls regularly show that less than half of Americans who graduate from U.S. colleges and universities accept the theory of evolution.

How to tell science from mumbo jumbo? Honest scientists admit that there is a certain amount of mumbo jumbo in most science and a certain amount of science in most mumbo jumbo. Separating the two is a matter of evaluating evidence. This book emphasizes the rules of evidence in a field of intersection between psychology and animal behavior. Scientific rules of evidence only lead to relative answers. All scientific evidence may be flawed but some evidence is more flawed than other evidence. This book aims to show how the difference between poor evidence and better evidence, though always relative, is well worth the effort.

Books that offer an encyclopedia-style compendium of current theory and research are often truly valuable introductions to a field. A compendium can also be a valuable addition to a reference shelf, providing that the definition of “current” is wide enough to keep the contents from falling rapidly out of date. The trouble with a compendium is that it must sacrifice depth of detail for breadth of coverage. It must omit basic details of evidence. Within the covers of a compendium, readers must accept predigested assertions on faith as received wisdom. This common practice dulls rather than sharpens any taste for inquiry.

The primary subject of this book is the tools of inquiry in this field. Consequently, descriptions of experiments and series of experiments that build on each other appear in some depth, more depth than in the usual compendium. Experimental methods usually have an instructive history. Early questions and early techniques lead to more advanced questions and advanced techniques. Later experiments build on the successes and failures of earlier work. This book shows how experimental operations develop from experiment to experiment by describing experiments in historical series and in enough detail to show continuity.

This book offers enough detail and background information to make it accessible to nonspecialists. The same rules of evidence are useful in many related fields. Skill in relating theoretical interpretation to experimental operations should transfer beyond the limited number of topics in this book to other topics in this field as well as to topics in related fields. Mastering this skill is at least as valuable as mastering a compendium of predigested facts and theories, and many students and colleagues find it more exciting.

The strategy of this book is to provoke interest in experimental operations by questioning traditional views. Many readers are surprised to find that it is possible to question folk wisdom about reward, punishment, and cognition. Attempting, and sometimes failing, to defend the traditional view, is a way to find out how advances depend on operational definition.

In contrast with the top-down, feed backward viewpoint of tradition, this book offers a bottom-up, feed forward alternative, which has the advantage of freshness and novelty for many beginners. Contrasting traditional views with reasonable alternatives is a way to get readers to attend to crucial problems of experimental operations. This book presents the major traditional positions in detail, but it demands that readers examine evidence, recognize weaknesses, and consider alternatives.

Inexpensive videotape technology has brought a steadily increasing amount of ethological observation into modern conditioning laboratories. The results of these ethological observations have profound implications for basic theories of learning. This book emphasizes these implications and relates them to classical questions in the ethology and experimental psychology of learning.

Recent developments in computer science have produced a new breed of autonomous robots and autonomous system controllers. Modern robots and system controllers are truly autonomous. Like living systems they operate spontaneously under unexpected conditions. The new breed of autonomous robots and controllers operate on bottom-up principles that are refreshingly ethological. These advances in computer science have profound implications for basic theories of learning. This book emphasizes these implications and relates them to basic problems in the ethology and experimental psychology of learning.

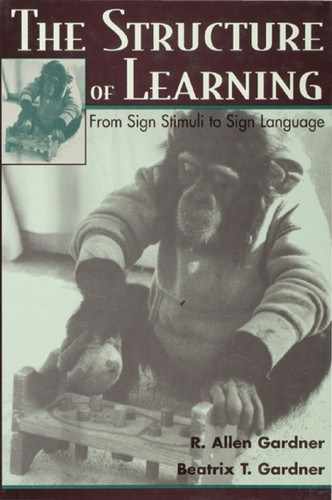

Beatrix Gardner and I collaborated on earlier versions of this book until her recent death, which left me to bring it to its present form. When we met, she had just returned to American experimental psychology fresh from taking her D.Phil. in Zoology at Oxford with the nobelist Niko Tinbergen, a towering figure in experimental ethology. My mentor had been Benton J. Underwood of Northwestern, known throughout his career for experimental methods in the study of learning. Our sign language studies of cross-fostered chimpanzees express a life-long interest in ethology, learning, and experimental operations. Those studies grew out of the same principles that led to this book and appear appropriately in the concluding chapters. They extend the principles of the earlier chapters with unusual conditions and tasks, and with free-living, well-fed, nearly human, experimental subjects as opposed to rats and pigeons in boxes. They also show how rigorous laboratory studies can apply to broadly interesting scientific questions.

Although we planned from the beginning to write a book like this one, our sign language studies of chimpanzees absorbed most of our efforts for many years. Meanwhile, a wave of new experiments appeared that challenged the folk wisdom in traditional theories and traditional books. By now these findings have been well documented and thoroughly replicated. The new findings point to the same ethological pattern, in the nursery school and the Skinner box, in rats and pigeons, in children and chimpanzees. At the same time, fresh developments in computer science offer fresh insights into the behavior of autonomous living systems. It seems like a good time to incorporate the new developments into this new book.

Allen Gardner